Introduction

Lack of funding is a major barrier to advances in ecology and related fields in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) (

Bloch et al. 2014). Funding supports research, the pursuit and investigation of novel ideas, and the career development and livelihood of researchers; in contrast, a lack of funding can limit opportunities, lead to frustration, resentment, and ultimately, an exodus of talented researchers from the field (

Basken and Voosen 2014;

Daniels 2015)—often in search of more stable and remunerative financial arrangements (

Wong et al. 2022). This is especially true for early-career researchers (ECRs; e.g., graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, assistant professors), who are developing their own research programs and have not secured long-term employment positions.

Individuals from racially diverse backgrounds have been disproportionately and systemically underrepresented as funding recipients in STEM fields (

Chen et al. 2022). This likely begins at the early-career stage with individual research funding, where it has been shown that success or lack thereof in acquiring funds is not only a predictor but a contributing factor to future success (or failure) (i.e., the “Matthew effect”;

Bol et al. 2018). Here, we refer to funding and grants as any type of financial award, including research and stipend funding, with the potential to impact an ECR’s retention in their field. A pattern of biased funding persists despite recognition that access and opportunity to pursue a career in STEM fields should be available and equitable to all, and despite evidence that diversity in research groups increases research quality and output (

Harding 1998;

Swartz et al. 2019). The broad lack of funding for ecology-related research is documented (

Kuebbing et al. 2018), but Black, Indigenous, other people of colour (BIPOC), and individuals from other historically underrepresented and marginalized backgrounds often face additional and compounding barriers that limit their ability to secure competitive funding. For example, fewer opportunities at the undergraduate level and a lack of mentors from similar backgrounds can exacerbate difficulties in establishing a career (

Strayhorn 2010;

Whittaker and Montgomery 2012;

Grossman and Porche 2014). As a result, non-White representation among early-career STEM grant recipients and working professionals is disproportionately low in North America. Despite comprising approximately 40% of the census population in the United States, ethnic and racial minorities received less than 7% of grant and philanthropic funds in general in 2013 (

D5 2016). They also comprised less than one third of employed biological, agricultural, and environmental life scientists and made up less than 5% of scientists in the ecology-related fields of forestry and conservation in 2017 (

Burke 2019). Comparable national statistics from Canada could not be found, and data on the demographics of funding recipients are generally scarce—although some specific grants and organizations (e.g., National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada; NSERC) report on the equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) patterns in their funding opportunities. Programmes that distribute grant funds have the potential to help rectify these gross inequalities by advancing diverse and equitable representation among early-career funding applicants and recipients.

Barriers throughout the careers of scientists from historically underrepresented and marginalized backgrounds are increasingly acknowledged (e.g., see

Whittaker and Montgomery 2012;

Lee et al. 2020;

Wanelik et al. 2020) and have been addressed in various ways around the world. In Canada, recent efforts by funding institutions and the federal government are working to improve diversity, representation, and retention of racial and ethnic minorities in ecology. For example, the Tri-Council of federal agencies (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council) initiated a 7-year EDI plan (2018–2025); the Canadian Chairs Research Program also implemented, under federal legal orders, an EDI action plan in 2021 for institutions to achieve equitable distribution of research chair positions, focusing on Indigenous Peoples, racialized minorities, women, and persons with disabilities. The action plan also includes staggered targets to meet by 2029 based on national population demographics, with funding and other consequences if targets are not met. Many organizations have also released diversity statements to outline the importance of EDI to their mission and the ways they support diversity. However, a clear and cohesive framework with specific recommendations for how agencies and organizations can improve diversity across grant stages is lacking. Thus, important work still remains with regard to developing, implementing, and assessing the effectiveness of EDI efforts.

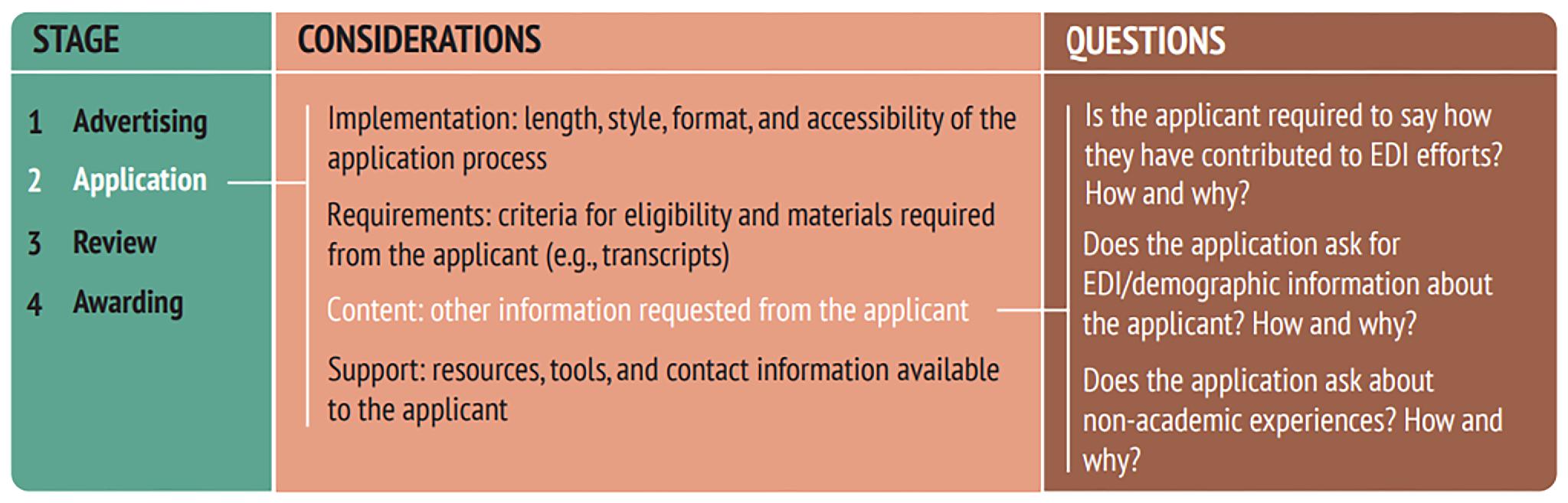

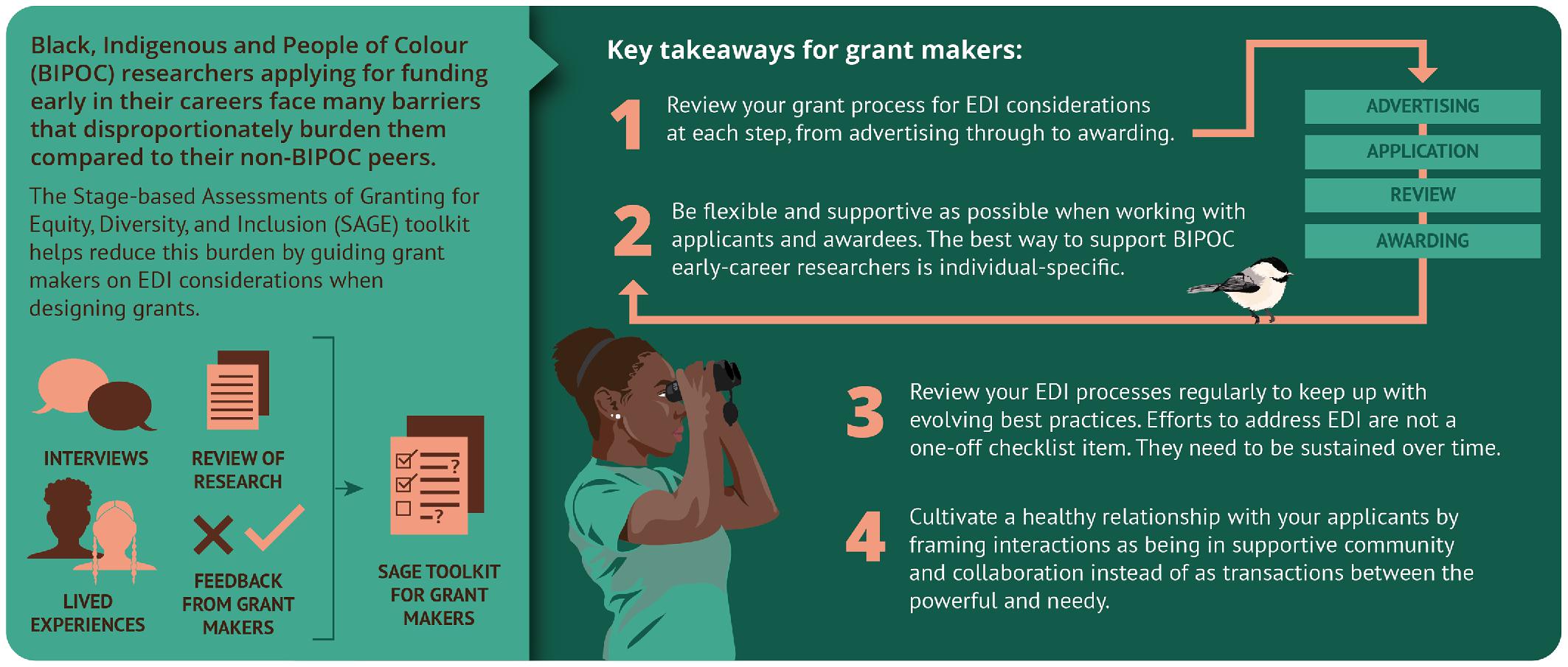

Borne out of the coauthors reflecting on the apparent lack of EDI amongst ecology ECRs in North America and the shortage of organized recommendations for funding agencies and grant makers, we developed the Stage-based Assessments of Grants for EDI (SAGE) toolkit (Supplementary Materials A). The SAGE Toolkit highlights steps that Canadian and other funding agencies and grant makers can consider in their EDI efforts when assessing their funding programs to increase sustained diversity among award applicants, recipients, and the larger scientific community. The SAGE Toolkit is organized in an applicant-centered way, into the Advertising, Application, Review, and Awarding stages that early-career BIPOC and those from other underrepresented backgrounds experience and interact with when seeking funding. Advertising refers to the materials and process by which funding announcements are circulated to potential applicants; the Application stage encompasses the information required of applicants and its submission process for evaluation; the Review stage includes the development, training, and activities of the people who review applications and recommend grant recipients. Finally, the Awarding stage involves the conditions for funds disbursement and communications between agency and applicants after funding decisions have been made. At each of the four stages, we identified components relevant to EDI and provide justification for their importance (e.g.,

Fig. 1). We include recommendations and steps for increasing EDI and offer examples where funding agencies are already working towards improving EDI. The recommendations are general but meant as a starting point for discussion and evaluation of current practices. Our hope is that grant administrators and decision makers can use the SAGE Toolkit to iteratively assess performance, reflect, and improve over multiple grant cycles. Funding agencies should commit to continued efforts to seek the most current EDI best practices—which evolve rapidly—and also to reflect on how these recommendations are relevant to the specific demographics they serve or aspire to serve. Our toolkit emphasizes BIPOC and racial EDI, as this has been a prevalently discussed inequality across funding opportunities in ecology and related fields (

Duc Bo Massey et al. 2021;

Chen et al. 2022). However, our recommendations are relevant for many axes of identity and backgrounds that are underrepresented and often left out of equitable consideration for grants—especially due to intersectionality, which is both the connectedness of multiple axes of identity (

Parent et al. 2013) and subsequent complex impacts of discrimination (

Bowleg 2012;

Bauer 2014).

To create the SAGE Toolkit, we used multiple sources of information and knowledge. Our objective was to develop a useful toolkit for advancing EDI, rather than to identify all possible considerations or to conduct a comprehensive review of all Canadian ECR funding opportunities in ecology. For each stage, at least three coauthors developed a preliminary list of considerations and corresponding recommendations for action. These lists were informed by reviewing Canadian funding opportunities with information available online (n = 19; listed in Supplementary Materials B) based on a combination of opportunistic searching and coauthors’ prior knowledge. Support for considerations and recommendations with references were gathered from grey and peer-reviewed literature and the extensive knowledge of the coauthors, who included researchers and other professionals in ecology with a range of identities, backgrounds, and experiences—both personal and career-related (see Positionality statement). We focused on grants from Canadian institutions and organizations (any organization or institution that holds award competitions for ECRs in Canada in the fields of ecology or evolution) because there is a lack of available information about EDI in Canadian funding for ecology and related fields. We used public information available online because transparency is important for advancing EDI and promoting accountability. Variation in available information led to some stages, considerations, and recommendations having more citations and references than others, but all were reviewed and endorsed through coauthor consensus.

Recognizing the diversity and positionalities amongst our coauthors, there was the opportunity to further validate and enrich the toolkit with the lived experiences and perspectives of select coauthors who self-identified as early-career professionals. To identify common themes related to ECRs’ pursuit of funding opportunities, we conducted semi-structured interviews with five coauthors. Interviews were conducted by a coauthor (AF) with expertise in administering semi-structured interviews. In one-on-one 45-minute audio calls, interviewees were asked about their career experiences in ecology as they pertained to the four stages of the grant process (Supplementary Materials D). Interviews were recorded, each transcribed by the respective interviewee, and analyzed in two rounds by the interviewer (AF) to identify thematic codes and subcodes. Further details about the interviews and analysis can be found in Supplementary Materials D. Approval for the semi-structured interviews was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of British Columbia (REB_H21-03284).

Finally, we collated the four stages into a unified toolkit and trialed its usability by applying it to the NSERC Banting and Yellowstone 2 Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y) grants. We further developed the toolkit based on group discussion, adding final justifications, examples, and recommendations. To increase adoption by funding agencies, we sought feedback from NSERC, the Liber Ero Fellowship Program, and Y2Y, which were chosen to reflect a range of funding amounts and sizes of funding agencies. We hired a science communicator and enlisted a French translator to develop English and French versions of an infographic and a two-page overview of the SAGE Toolkit (Supplementary Materials C) for funding agencies and programs. Below, we highlight and discuss major conclusions from each stage of the SAGE Toolkit.

Stage 1: Advertising

The Advertising stage is the first interaction between a funding opportunity and a potential applicant. Effective advertising of funding opportunities is critical for attracting diverse applicants. Where a funding opportunity is advertised (e.g., social media platforms, online job boards, university websites, etc.) directly impacts who will apply. Our semi-structured interviews provided further insight and revealed that lack of exposure to grants and other opportunities was a common barrier faced by underrepresented groups. Several interviewees also noted a lack of awareness about where to find training positions. To address this, agencies should consider advertising opportunities on a range of platforms and websites, as this can increase the likelihood that individuals from diverse backgrounds encounter the advertisement and potentially apply. Examples include minority serving institutions (msiexchange.nasa.gov) and programs such as the Strategies for Ecology, Education, and Diversity Sustainability (SEEDS) Program of Ecological Society of America. In some cases, ECRs from certain backgrounds may be approached or specific individuals may be recruited to apply in an effort to increase diversity in the applicant pool. Such active recruitment by grant administrators and past recipients can encourage those who might not otherwise consider the funding opportunity, but requires care to avoid selection bias from over-represented backgrounds. The Canada Research Chairs Program has been working on training requirements for all people involved in recruiting and nominating processes. For example, reviewers are encouraged to take the Status of Women Canada’s online introduction to Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) (

Government of Canada 2022a). Currently, this training appears to be optional.

The importance of language in advertising is well documented (

Johannessen et al. 2010;

Gaucher et al. 2011;

Wille and Derous 2017) and the language used to describe funding opportunities can impact an interested person’s decision to apply. Neutral and inclusive language maximizes the number of people who can self-identify as possible grant recipients (

Taheri 2020). For example, superlatives that describe ideal applicants or successful recipients as “exceptional” or “world-class” can cause potential applicants to self-doubt or not relate and therefore not apply. Furthermore, if funders are sincere about equitable granting and increasing diversity, advertisements should explicitly describe how the application process will accommodate and consider a spectrum of relevant experiences and expertise. The advertisement should include an EDI statement and explain measures in the review process intended to uphold ethics and reduce implicit biases (See the Review section below).

Stage 2: Application

The Application stage refers to information that funding agencies request of the applicant to consider. This stage details what applicants will be evaluated on and how those materials must be submitted. This stage represents the most work for applicants. The semi-structured interviews reflected this barrier, with the most responses related to struggles or issues faced at this stage of the grant process. For example, a barrier that multiple interviewees mentioned was the time and effort required to submit an application, and several viewed this as weighing trade-offs with other grant work, career opportunities, and responsibilities such as additional part-time employment. These experiences are mirrored in U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistic trends for multiple jobholdings (

U.S. Census Bureau 2023).

Applications should be submittable independently or through an institution that the applicant is affiliated with or attending. Applications for Canadian Tri-Council grants, for example, must be submitted through the institution that the applicant either currently attends or attended in the previous year. All other applicants may submit directly to the agency (e.g.,

Government of Canada 2022b). When submissions are through an institution, applicants may benefit from access to agency representatives or other staff based at the institution who specifically assist applicants and answer questions. However, institutions may add their own review or selection processes, or have their own EDI principles that are different from those of the funding agency—thereby creating potentially disparate standards among the larger pool of applicants. Furthermore, requiring applications to be through an institution can be prohibitive and a form of gatekeeping. Applicants may not align with institutional priorities or have limited options for institutional support due to a variety of reasons, including periods of no affiliation during transitions between short-term work contracts, or a return to education or research after time away due to other obligations. As peer-reviewed journals have been called the “gatekeepers of science” (

Crane 1967), requiring university affiliation poses similar barriers for ECRs. Therefore, independent applications submitted directly to the grant agency can be more accessible and made available to those who do wish or are unable to affiliate with an institution. Funding opportunities should consider if both options are possible to encourage applications from a broad range of ECRs, and work with institutions to ensure standardized review and selection processes.

The application interface can also play an important role. Applications requiring submission in multiple stages rather than a single one can reduce the workload for both applicants and reviewers. Initial brief proposals deemed promising may be invited to submit a more in-depth application for further consideration with greater chance of success, thus reducing the workload across the applicant pool as well as for reviewers. Application questions and required documents should be clear and known from the outset, rather than dispensed in sections, so that applicants can plan how to allocate time when preparing responses. This is especially important for first-time applicants and those with no access to other support resources. Finally, access to and submission of applications are often done through an online web portal, but access to reliable internet can be challenging for some applicants (

Fabito et al. 2021) and should not be assumed. Additional forms of submission, including physical mail and email, and Word or PDF documents should be considered, balancing agency capacity while accommodating a range of accessibilities.

Many technical components of the application materials also present opportunities for supporting EDI. The various types of documentation and eligibility criteria should be carefully selected and not just be based on precedent. ECRs from underrepresented backgrounds may not meet traditional expectations of citizenship, times since degree, or access to materials such as transcripts or references. The Liber Ero Fellowship Program, for example, focuses on research conducted primarily in Canada but does not require applicants to be Canadian (

Liber Ero Fellowship Program 2023). Multiple letters of reference can also be a barrier for those with less experience or extenuating circumstances that affect their ability to obtain multiple references. At a minimum, the number of such requirements should be commensurate with the size of the award and the amount of work required to provide those materials in the application. Indeed, some applications for small funding opportunities require as much work as larger ones, but could be restructured to serve as simpler entry points for funding. Also, application timelines and important dates should be clearly communicated, and agencies should provide answers to frequently asked questions and contact details of people to whom applicants can reach out. This is especially important for first-time applicants who may not have a network to draw from for experience or resources. Expected deadlines, timelines for updates, and the evaluation guidelines allow applicants to effectively allocate their time and effort.

Applications frequently ask for evidence of relevant academic experience or contribution to EDI efforts. These requirements should be flexible and allow applicants to respond in a nuanced way, as they can be problematic for ECRs from historically marginalized and underrepresented backgrounds with responsibilities and additional burdens that are not immediately apparent. For example, interviewees noted the need to work multiple jobs outside their research, which they felt may have affected measures of “traditional success” in academia. Thus, there should be opportunities to illustrate capacity, ability, and potential—especially with relevant non-academic experience. Also, ECRs from underrepresented, equity-deserving groups often face disproportionately more pressure to do EDI work compared to other ECRs (i.e., the “minority tax”;

Trejo 2020;

Williamson et al. 2021). This additional burden may not come across in an application, but should be taken into account as applications increasingly request that applicants describe their contribution to EDI efforts. Indeed, whether applicants should describe their contribution to EDI efforts as part of their application was brought up in feedback from funding agency representatives. We challenge this requirement, as marginalized people do not need to be further burdened with incorporating EDI into their professional work, especially if EDI is not strictly relevant to the research topic. Instead, applications may ask for a short-written statement about the applicant’s awareness of or relationship with EDI, thereby actioning the funding opportunity’s interest and commitment to advancing EDI.

Finally, applicants are increasingly being asked to report their identifying markers (e.g., race, gender, pronouns, etc.). This is often done to track EDI efforts. Funding agencies should clearly communicate exactly why and how this information will be used (

Guichard and Ridde 2019). For example, the Tri-Agency Self-Identifying Questionnaire for applicants is accompanied by an FAQ section to explain the collection of information on eight dimensions of identity (age, gender identity, sexual orientation, Indigenous identity, visible minority, population group, disability, language) (

Government of Canada 2021). Applications should request information in an inclusive way (

University of British Columbia 2019); write-in options for self-identification should be available in addition to discrete/multiple choice formats. Importantly, applicants should be able to select all the choices that apply (

Canada Council for the Arts 2019). Applicants who identify with multiple marginalized, equity-deserving groups may be consistently passed over for consideration due to funders incorrectly assuming that the applicants may receive support elsewhere based on each of those marginalized axes. Therefore, multiple axes of identity and under-representation should be included and available for selection to fully capture and therefore provide the opportunity to correct how intersectionality can disproportionately disadvantage those who identify with multiple marginalized and under-represented groups (

Miriti 2020). Ultimately, providing identity information should be optional, as it may pose a safety risk or be too private for applicants to share.

Stage 3: Review

The Review stage is pivotal for supporting EDI in ecology and related STEM fields, as it determines which applications—and therefore ECRs—receive funding and have the chance for longer-term career success (

Bol et al. 2018). A common and reasonable determining factor at the Review stage is perceived scientific rigor and topic appropriateness of the application. Funding agencies have begun to embrace more diverse modes of research (

O'Malley et al. 2009), but narrow definitions of scientific rigor and appropriate or relevant research topics can disadvantage certain demographics and historically underrepresented groups (

Hoppe et al. 2019). For example, funding opportunities may be biased to fund research situated within the traditional framework of hypothesis testing despite other rigorous and scientific approaches for identifying and understanding natural and complex ecological patterns and processes (e.g.,

Quinn and Dunham 1983). Funding agencies should interrogate their positions on the scientific process, make room for creative and non-traditional topics and approaches, and importantly, ensure that review processes are aligned with equitable consideration towards diverse applications. Reviews should consider the potential of the research and applicant and place a limit on the weight of evidence of past success, which marginalized ECRs may have fewer of due to lack of previous opportunities, resources, and access. We reiterate the recommendation of

Hoppe et al. (2019) to support funding of under-appreciated topics that nevertheless are worthy and aligned with the funding agency’s priorities. We suggest that applications from individuals who self-identify as from historically underrepresented groups be identified or earmarked for review with special attention, as this would demonstrate that funding agencies are actively working to redress the history of marginalization and negative impacts of intersectionality.

Our review of Canadian ECR funding opportunities suggested that agencies, especially larger ones, were relatively forthcoming about the rules and procedures within the Review stage, consistent with

Gurwitz et al. (2014). Interestingly, we also came across more peer-reviewed literature about the review process investigating the peer-review process compared to the other stages, perhaps due to biases known to impact reviews and evaluations (

Tamblyn et al. 2018). We identified the development and training of the review panel members (i.e., reviewers) as important for supporting EDI. Panels should reflect or at least actively hold space for the diversity sought among grant applicants and recipients, which can increase the chances of fair evaluation of the entire range of merits and shortcomings of applications (

Stevens et al. 2021). Semi-structured interviews revealed a lack of diversity and representation among mentors of ECRs as a barrier to inclusion, so it follows that intentional composition of the review panel is part and parcel of dismantling this barrier. Agencies should also consider publishing the identities of past reviewers. Previous grant recipients should be considered for review panels or advisory boards, but care must be taken to avoid disproportionately burdening ECR reviewers from underrepresented backgrounds. For example, reviewers for the postdoctoral NSERC Banting Fellowship serve a maximum of three grant cycles. Furthermore, bias can be reduced with preparations such as the unconscious bias training that Tri-Council provides, EDI education, and codes of conduct. For example, reviewers for the Banting fellowship must also agree to adhere to a code of conduct (

Government of Canada 2022b). Additional strategies, however, such as blind reviews (

Lee et al. 2013) to help guard against implicit biases (

Smith et al. 2015) should also be considered because one-off training may have only temporary benefits and have varying effects across individuals (

Chang et al. 2019).

Transparency is integral to quality and ethical reviews. Transparency promotes accountability and professionalism (

Cornielle et al. 2019), which helps develop trust between applicants and funders and contributes to more equitable review processes for historically under-represented and marginalized groups (

Silbiger and Stubler 2019). Recording scores and justifications for how applications are evaluated or ranked allows for decisions that can be reviewed, modified, defended, and shared. Benefits of an explicit rubric include recalling priorities, reducing bias, and maintaining consistency across reviews, while space for additional comments provides opportunity for nuance. Rubrics can also be a valuable source of feedback for both funding agencies and applicants. Finally, roundtable meetings for reviewers to discuss evaluations are helpful for correcting biases, creating consensus, and generating helpful insights for future granting cycles. Given the systemic disadvantage that ECRs from underrepresented backgrounds have faced, transparent standards to which reviewers must adhere can hold funding agencies more accountable to their EDI objectives.

Stage 4: Awarding

The last stage of a grant process involves the actual awarding of funds. The Awarding stage is generally publicized and therefore visible to many for assessing an agency’s or program's EDI efforts. However, we found few published resources about or evaluating awarding practices related to EDI, so many of the components and recommendations identified at this stage are based on the lived experiences of the coauthors. Notably, awarding conditions and communications between the funder and applicants provide opportunities for collaborative relationships between the two parties. Dialogue is crucial; conditions and requirements should be clear before applications are submitted because they could present barriers to accepting funding, but funding agencies should be open to discussing and amending conditions when grant recipients have compelling or extenuating circumstances. For example, some granting agencies may have conditions for simultaneously holding multiple awards. NSERC Banting fellowships for example, allow awardees to hold one Tri-Council award in addition to the Banting award. Furthermore, recipients may not be aware that it is possible to tailor conditions or to even ask and self-advocate (

Wiltshire et al. 2006). Grant recipients of colour often receive smaller awards (

Dorsey et al. 2020) in part due to lack of self-advocacy in proposed budgets, and funders should consider this and be transparent about whether awards are based on predetermined amounts or proposed budgets. If the latter, it should be possible to award more than the proposed budget. Other conditions may restrict how funds are distributed (e.g., annually, monthly, through an institution or directly, etc.) or used (e.g., restricted vs. unrestricted funds), impact the options for funding extensions, and include stipulations for reporting on project updates. Importantly, conditions should be minimal and justified, and such grant support should be maintained in the case of unexpected circumstances.

Communication between the funding agency and applicants at the Awarding stage has lasting benefits for EDI beyond a single grant cycle. The unique perspectives of applicants can highlight gaps where granting processes can improve, and funding agencies should be receptive to and solicit feedback from applicants. Semi-structured interviewees expressed frustration about the lack of explanation for why applications were unsuccessful or why some applicants were successful over others. This can translate into substantial anxiety for ECRs because it represents a missed learning opportunity to improve future funding proposals. Therefore, an important juncture for communication occurs when decisions are sent to applicants. The ubiquitous generic message (e.g., “unsuccessful due to an overwhelming number of competitive applications received”) offers no solace to the unsuccessful applicant and can in fact be harmful by discouraging future attempts to secure funding (

Bol et al. 2018). Rather, funding agencies should strive to provide feedback about application strengths and weaknesses; this is especially beneficial for applicants with little to no additional resources with which to improve future funding attempts and those who were not awarded but still had strong applications (

Bol et al. 2018). Scores and select comments from the Review stage (see Stage 3: Review) are a relatively easy source of such feedback that we recommend be provided to applicants; in which case, reviewers should be made aware their comments will be shared with applicants. This approach would require additional capacity from the funding agency to review and organize feedback, although training and safeguards in the Review stage to assure reviewer conduct and transparency should reduce this workload. Such efforts would demonstrate a clear commitment to supporting ECRs and applicants from historically under-represented and marginalized groups.

Finally, funding opportunities should be intentional about sharing and publicizing results, such as on agency websites and social media platforms. For example, NSERC Banting and Y2Y publish the names of past recipients on their websites (

Government of Canada 2022c;

Y2Y 2023). Reporting statistics about the final decisions (e.g., percentage of successful applications) and EDI metrics (as NSERC does), and publicizing recipient biographies or profiles help demonstrate that the funding agency’s intentions to increase EDI are tracked and followed through with action. Indeed, interviewees noted a lack of diversity among grant recipients as a potential barrier to even applying for a funding opportunity. The coauthors struggled to find statistics and data on EDI for many Canadian funding awards, pointing to an area with significant room for improvement and transparency. Clearly, shining a light on the black box of the Awarding stage is a chance for funding agencies to cultivate more interest from potential diverse applicants. This connection to earlier stages of the grant process highlights how EDI at each stage is critical for supporting ECRs.

Conclusions

In recent years, agencies and institutions have been confronted with the lack of diversity among researchers at all career stages, and efforts have been made to address this disparity. The SAGE Toolkit breaks down the grant process into the applicant-centered Advertising, Application, Review, and Awarding stages to highlight specific areas where funding agencies can more effectively attract and serve BIPOC, and generally a more diverse pool of applicants. Many of the considerations and recommendations are generally already recognized as good practice in various aspects of research, funding, and mentorship, but the SAGE Toolkit provides a unified and coherent collection for the explicit purpose of supporting EDI in ECR funding. It is the responsibility of funding agencies and programs to determine for themselves how and when to best engage, adopt, and implement relevant components and recommendations in the SAGE Toolkit. Agencies should be mindful of how this work is distributed across its human resources (

Trejo 2020;

Williamson et al. 2021), and endeavor to embody these efforts to advance EDI at all hierarchies of their decision-making and power structures. The hope is that such efforts and actions translate into diverse grant recipients, supported ECRs, and an equitable, inclusive, scientific community. While it can be difficult to change longstanding practices, we believe that an honest reflection of funding missions paired with iterative use of tools, starting with the SAGE Toolkit, can contribute to advancing EDI in ecology and related fields beyond performative statements and gestures (

Fig. 2).

Our work indicates that awarding funds to individuals from underrepresented racial backgrounds is insufficient for advancing EDI in ecology and related STEM fields. Funds reach a small proportion of applicants, and increasing EDI should involve action throughout the grant process. Opportunities exist at all four stages that would benefit all applicants. Furthermore, funding opportunities should strive to be flexible when working with applicants and grant recipients, as supporting ECRs is individual-specific. Importantly, efforts to increase EDI must not be one-off exercises, but rather be made with a long-term focus based on evolving best practices. Indeed, we recognize that the SAGE Toolkit should be dynamic and open to additions and changes. In the toolkit, space at the end of each stage allows for additional considerations, justifications, and recommendations. The most up-to-date SAGE Toolkit can be found online at bit.ly/ediSAGEtoolkit. Our work focused on EDI in early-career funding for individuals, and we acknowledge that non-profit organizations and programs with minority-serving missions face similar challenges with philanthropic funding. We note that academic and philanthropic institutions also serve an important role in the funding process and call on them to consider the toolkit criteria for internal awards. For members of racialized, historically marginalized, and equity-deserving groups, we recognize that choice in which funding opportunities to apply for can be a luxury and is not always possible. We encourage applicants to self-advocate when it is safe, and to seek out resources, clarifications, allies, and other advocates whenever and wherever possible. We call for continued work across all types of funding opportunities and support mechanisms to advance EDI in ecology and related STEM fields. Finally, the process of developing this toolkit—from the collaboration of its diverse coauthors to the recommendations provided in the SAGE Toolkit and its proposed iterative application—highlights the potential for shifting the relationship between funding agency or opportunity and applicant from a transactional dynamic between the powerful and needy to one of supportive community and collaboration.

Positionality statement

The coauthors are a group of multi-cultural, multi-generational, and international researchers, academics, and administrators. Career stages amongst the coauthors range from early to established and included students, researchers, professors, EDI experts, grant recipients, administrators, and reviewers. Some are from colonizer/settler backgrounds, while the majority are from multiple axes of identity that have been systemically marginalized in settler society, research, and academia. Six also self-identified as ECRs. We recognize that EDI work falls often on equity-deserving people and acknowledge that our collective positionalities motivated and actively informed this work. The coauthors have all experienced success in traditional academic and professional settings to varying degrees in our careers in ecology-related fields—as evidenced by all holding at least one graduate degree and having university or organizational affiliations at the time of this work. Therefore, we recognize the complex and collective nature of the work that is needed to contribute to and see a more equitable, diverse, just, and inclusive scientific field.