Introduction

In recent years, increasing attention has been directed to “natural climate solutions” (NCS) or “nature-based climate solutions” to protect and restore carbon-storing ecosystems as a component of climate change mitigation (

Griscom et al. 2019;

Seddon et al. 2019;

Drever et al. 2021). Recent studies demonstrate the global significance of carbon sinks in Canada, such as the Boreal Forest and the Hudson Bay Lowlands, the world's second largest peatland complex (

Harris et al. 2022;

Sothe et al. 2022). Action (or inaction) to protect such ecosystems can alter the pace of global climate change; thus, advocates suggest that Canada has a disproportionate responsibility to implement NCS (

Harris et al. 2022).

Concurrently, Canada has a responsibility to advance reconciliation with and uphold the rights of Indigenous Peoples. The imperatives for climate action and reconciliation are deeply intertwined. Given the overlap of Indigenous territories and carbon-rich ecosystems in Canada, NCS projects threaten to undermine reconciliation efforts unless Indigenous Peoples' rights, sovereignty, and historic stewardship roles are respected (

Townsend et al. 2020;

Reed et al. 2022). Moreover, in practical terms, Indigenous Peoples have been implementing NCS for millennia in North America (also known as Turtle Island) and around the world and have a wealth of knowledge to continue doing so to successful ends (

Townsend et al. 2020). In 2019, for the first time, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recognized that strengthening Indigenous rights is a critical solution to the climate crisis (

IPCC 2019), to which Indigenous Peoples and local communities from 42 countries responded, “Finally, the world's top scientists recognize what we have always known” (

Rights and Resources Initiative 2019). As political support grows for NCS, Indigenous Peoples in Canada are calling for recognition of their historic and ongoing role in stewarding natural carbon sinks and are asserting their rights as necessary beneficiaries of stewardship activities in their traditional territories (

Townsend et al. 2020).

Alongside the growing movement for Indigenous-led NCS, communities are revitalizing and reclaiming land stewardship roles, including under the banner of “Indigenous Guardians”. With support stemming from advocacy by the Indigenous Leadership Initiative, over 120 Indigenous Guardians programs have been established in Canada, through which communities are engaging in a range of monitoring and management activities to care for the land, waters, and wildlife within their traditional territories (

Land Needs Guardians 2022).

Guardians programs are well-positioned to operationalize and benefit from NCS. Implicitly, Guardians are already facilitating NCS by protecting and restoring ecosystems that mitigate climate change. Through more explicit alignment, there may be an opportunity for Guardians, should this be of interest to them, to expand their climate impact and benefit from direct funding for NCS and/or carbon credits. The significance of this possibility is underscored by the fact that Guardians programs are largely reliant on finite federal funding and seek longer term, sustainable financial solutions.

Within this context, a number of questions arise. What possibilities emerge when NCS are driven by Guardians and guided by multifaceted community priorities? What might NCS look like if it were rooted in a holistic approach to “climate action” and informed by Indigenous knowledge systems as opposed to the Western convention of compartmentalizing social, ecological, and climate-related issues? And given that Guardians programs emphasize intergenerational learning and include youth programming, what do youth Guardians themselves envision at the intersection of guardianship and NCS?

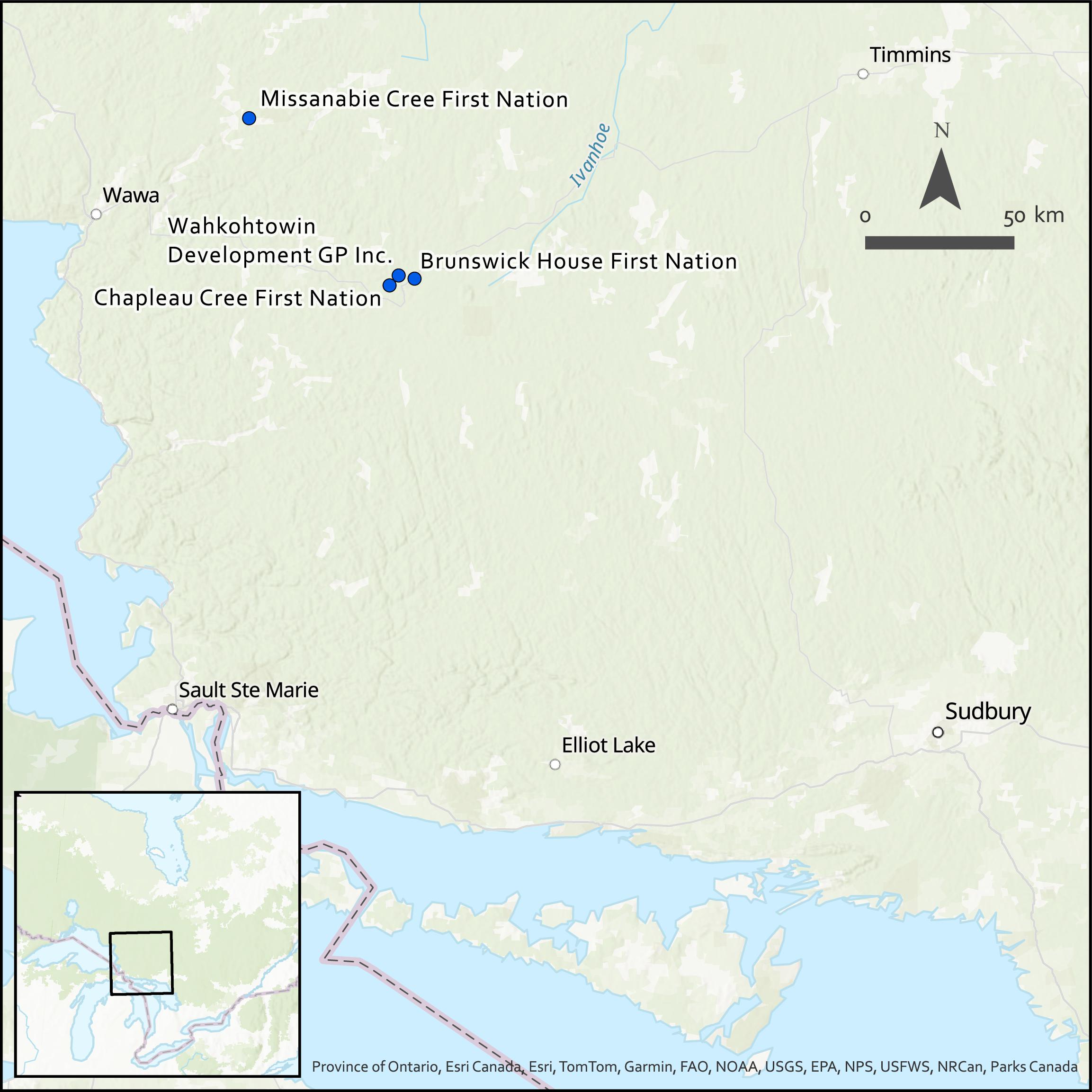

This paper responds to these questions drawing upon recent experiences of an Indigenous-owned social enterprise in Ontario, Canada, Wahkohtowin Development GP Inc. (Wahkohtowin), which is leading an effort to integrate NCS with its youth-focused Guardians program to build opportunities for its owner First Nations: the Missanabie Cree, Chapleau Cree, and Brunswick House First Nations. As an initial step toward interweaving NCS and climate action within the Guardians program, Wahkohtowin held a Guardians Climate Action Initiative in partnership with the University of Guelph. We (co-authors and additional Wahkohtowin staff) hosted a series of workshops over two months in early 2022 to engage Guardians in discussions on climate action, including NCS, which culminated in a youth-led film and webinar. Recognizing the limitations of traditional academic inquiry for achieving our mutual aims, the Climate Action Initiative was guided by a decolonizing, iterative approach focused on youth empowerment and aligned with the broader purpose of the Guardians program.

Leveraging insights from the Wahkohtowin Guardians Climate Action Initiative, both its outcomes and the approach itself, this paper explores opportunities for NCS driven by, and supportive of, Indigenous Guardians, with particular attention to youth perspectives and leadership. Ultimately, we suggest that when grounded in Indigenous ontologies (such as the Cree or nêhiyawahk principle of wahkohtowin, meaning “everything is related”), Indigenous Guardians offer a pathway for NCS that can enable multiple intersecting benefits, including climate change mitigation and biodiversity, cultural revitalization, economic development, youth empowerment, and reconciliation.

The paper follows in four parts. In the next section, we contextualize the Climate Action Initiative within Wahkohtowin's longstanding work and the broader movement around Indigenous-led conservation, Indigenous Guardians, and NCS in Canada. Next, we outline the approach used to facilitate dialogue on climate action and NCS among the youth Guardians. Subsequently, we discuss themes that emerged from the dialogues, situating the Guardians’ insights within broader opportunities for Indigenous-led climate action and specifically NCS. Namely, we explore the value of a holistic and ethical approach to “climate action” vis-à-vis NCS and guardianship, the need for decolonized cross-cultural collaboration, and broader considerations for youth- and Indigenous-led climate action. In the paper's concluding section, we propose an integrative, Two-Eyed Seeing approach to NCS that centres Indigenous knowledge and youth empowerment via Indigenous Guardians to enable benefits including and beyond climate mitigation.

Background

NCS encompass a range of actions that mitigate climate change by leveraging or enhancing ecosystems’ natural ability to capture and store greenhouse gases such as carbon. These actions most commonly entail the protection, sustainable management, and restoration of forests, wetlands, peatlands, and other natural carbon sinks. For example, given the capacity of forests to sequester and store carbon in tree biomass and soil, the protection of forests—“avoided forest conversion”—is an example of NCS (

Griscom et al. 2017). NCS can also include improved forest management for the purpose of increased carbon storage (

Griscom et al. 2017).

Though critics have raised concerns that NCS discourse and policy divert attention from the root causes of climate change

1 (

Goldtooth 2010;

Indigenous Climate Action 2021), research indicates that—

alongside steep reductions needed in fossil fuel emissions—NCS can significantly reduce global net emissions and thereby represent an important tool for climate change mitigation (

Anderson et al. 2019;

Griscom et al. 2019). Of course, this opportunity is paired with a real threat should our landscapes be left unprotected; boreal and peatland ecosystems in Canada store “irrecoverable carbon”, meaning that, if disturbed, vast stores of carbon will be released into the atmosphere that could not be restored by 2050—when the world must reach net-zero emissions to avoid the worst impacts of climate breakdown (

Noon et al. 2022).

2 On a global scale, studies have suggested that NCS could enable 30%–40% of the reduction in carbon dioxide emissions needed to cap global warming below 2 °C by 2030 (

Griscom et al. 2017). NCS are shown to be readily deployable and cost-effective solutions (

Griscom et al. 2017). As the benefits of NCS become clear, such solutions are increasingly prominent in climate change policy (

Seddon et al. 2020). For instance, in 2020, the Government of Canada committed to investing $4 billion in NCS over the next 10 years.

Indigenous knowledge and leadership are critical to the success of NCS since Indigenous Peoples have, in practical terms, been implementing such solutions since time immemorial. In the Canadian context, Indigenous leadership has been central to NCS implementation thus far (

Vogel et al. 2022). In fact, efforts to promote NCS will likely fail if Indigenous peoples are not centered (

Townsend et al. 2020). Internationally, a growing evidence base demonstrates the critical role of Indigenous Peoples in safeguarding biodiversity and stewarding carbon-rich ecosystems. At least 36% of the world's remaining intact forest landscapes fall within Indigenous People's lands (

Fa et al. 2020), and Indigenous Peoples manage at least 22% of the total carbon sequestered by tropical and subtropical forests (

Rights and Resources Initiative 2019). Further, Indigenous-managed lands have equal or higher biodiversity than state-led protected areas (

Schuster et al. 2019).

The success of Indigenous stewardship is largely attributed to robust, place-based epistemologies and ontologies developed over millennia (

Aikenhead 2011). While highly diverse, Indigenous knowledge systems often share commonalities, including ethics of responsibility and reciprocity with Creation (

McGregor 2004), Mother Earth (e.g.,

okâwîmâwaskiy in Cree (

Napoleon 2014)), or “all our relations” (e.g.,

M'sɨt No'kmaq in Mi'kmaw (

Marshall et al. 2021)). Traditional ecological knowledge can facilitate in-depth socioecological understandings of complex and long-term processes (

Molnár and Babai 2021) and localized and landscape-level ecological relationships (

Menzies et al. 2022). Furthermore, Indigenous ways of knowing and knowledge-building processes are shown to be highly adaptive and uniquely positioned for monitoring and interpreting environmental change (

Berkes 2009). These distinct features of Indigenous knowledge and their proven success in ecological conservation highlight the potential benefits of cross-cultural knowledge co-production within NCS planning and implementation.

Indigenous and allied scholars have long called for a re-centering of Indigenous knowledge within mainstream environmental governance discourse and practice (

Marshall 2004;

Houde 2007;

Mistry and Berardi 2016;

Moola and Roth 2019;

Rayne et al. 2020). To bridge Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge systems, various “linking frameworks” have been proposed and utilized. “Two-Eyed Seeing” or

Etuaptmumk is one such framework developed by Mi'kmaw Elder Albert Marshall based on the metaphor of “learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing, and to use both these eyes together, for the benefit of all” (

Bartlett et al. 2012, p. 335). A Two-Eyed Seeing approach presents evident benefits for NCS policy and practice.

Further, various Indigenous governments and advocates throughout Turtle Island are asserting that Indigenous Peoples are the rightful beneficiaries of new and future carbon management projects in their territories (

Townsend and Craig 2020). NCS must be implemented with the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent of Indigenous Peoples and uphold Indigenous land and resource rights, including carbon assets (

Townsend and Craig 2020).

Townsend et al. (2020) highlight the disproportionate vulnerability of Indigenous Peoples to both the impacts of climate change and to misguided forms of NCS like “fortress conservation” that protect lands through the displacement and dispossession of Indigenous peoples (

Adams and Hutton 2007;

Agrawal and Redford 2009;

Comberti et al. 2016;

Indigenous Circle of Experts 2018).

3 Considering this “twin vulnerability” and the significant overlap of Indigenous territories and carbon sinks in Canada, “questions about how [NCS] are developed, on whose territories, and with what outcomes matter deeply to the success of climate change policy as well as to the rights of Indigenous Peoples” (

Townsend et al. 2020). Thus far, these considerations have not been given enough attention; indeed,

Reed et al. (2022) contend that Canadian climate policy relating to NCS is failing to support Indigenous self-determination. Ultimately, without respect for Indigenous rights and the prioritization of Indigenous leadership, NCS threatens to undermine reconciliation efforts (

Indigenous Climate Action 2021;

Reed et al. 2022).

In contrast, if NCS are advanced under Indigenous leadership and with respect for rights to self-determination and Free, Prior, and Informed Consent, significant gains are possible. In addition to realizing domestic climate mitigation targets, Indigenous-led NCS initiatives are already generating sociocultural benefits like climate adaptation and resilience (

Vogel et al. 2022). Indigenous leadership may be conducive to a more holistic approach to NCS that maximizes beneficial outcomes beyond carbon sequestration, as indicated by the diverse aims motivating existing Indigenous-led initiatives. Indigenous governments are increasingly leveraging opportunities around NCS in their territories to advance sustainable development and economic diversification, self-determination, environmental protection, and cultural revitalization (

Townsend and Craig 2020). Such multifaceted aims are reflective of holistic ways of knowing that underpin Indigenous knowledge systems (

Battiste and Henderson 2000;

Levac et al. 2018;

Reed et al. 2022).

A holistic approach that acknowledges interconnectedness, aligns with the potential for NCS to simultaneously address the inextricably linked climate and nature crises (

Farber 2015). When effectively implemented, NCS like wetland conservation and improved forest management offer important ecological outcomes, including improved biodiversity, water filtration, flood buffering, soil health, and enhanced climate resilience (

Griscom et al. 2017). As such, in addition to mitigating climate change, NCS can play a key role in climate change adaptation, as well as in the achievement of Canada's Nature Legacy goals of conserving 25% of lands, inland waters, and oceans by 2025 on the path towards 30% by 2030 (30×30) (

Environment and Climate Change Canada 2022).

The need for an integrative approach to NCS that goes beyond carbon management is increasingly apparent given the growing body of evidence that climate action will be unsuccessful unless integrated with concerted efforts to protect biodiversity (

Farber 2015;

Corlett 2020;

Mori et al. 2021). Unfortunately, while the government of Canada claims to advance a dual aim of addressing both climate change and biodiversity loss through NCS (

Environment and Climate Change Canada 2022), there remains a gap between discourse and policy with respect to integrative approaches. For instance, ecological outcomes are often labelled “co-benefits” rather than central aims of equal import to carbon sequestration. Further, climate adaptation is largely unmentioned, despite the potential for biodiversity protection via NCS to help both nature and society build resilience in a changing climate (

Mori 2020).

Likewise, in addition to climate and ecological benefits, a more holistic conceptualization of NCS can enable positive social, cultural, and economic outcomes. Like “ecological co-benefits”, potential social outcomes for Indigenous communities are too often framed as “co-benefits” (

Simpson-Marran 2021), which is not only problematic in its siloed, non-holistic framing but, moreover, overlooks the fundamental importance of Indigenous rights and leadership within such conversations. The narrow framing of NCS is reflective of a broader propensity of Western science and policy to compartmentalize climate and conservation issues and interventions (

Hannah et al. 2002;

van Asselt 2011;

Carmenta and Vira 2018;

Mori 2020). This concern is well expressed in parallel scholarship centred on “biocultural” approaches (e.g.,

Cocks 2006;

Caillon et al. 2017;

Wall et al. 2023), “social-ecological systems” (e.g.,

Sterling et al. 2017), and Indigenous-led and decolonizing approaches linking climate, environment, health, well-being, and healing (e.g.,

Landry et al. 2019;

Redvers et al. 2020;

Galway et al. 2022).

While examples of integrative approaches are relatively recent within Western academia and policy, Indigenous Peoples across diverse cultures and contexts have developed “best practices” rooted in holistic knowledge systems over millennia (

Berkes and Berkes 2009;

Levac et al. 2018;

Mobley et al. 2020). Thus, as we later expand upon, Indigenous knowledge may be more conducive to an integrative approach to NCS framed around multidimensional aims, including and beyond carbon sequestration.

Aligning NCS with existing, related movements in Indigenous-led land stewardship may also help to maximize wide-reaching benefits. For instance, Nations and communities are increasingly pursuing Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas as a pathway to advance Indigenous sovereignty and biocultural and decolonial conservation (

Zurba et al. 2019;

Youdelis et al. 2021). Concurrently, a growing network of Indigenous Guardians appears well placed to implement and benefit from NCS. In 2015, the Assembly of First Nations passed a resolution of support for Land Guardians programs to support First Nations’ land management and monitoring (

Assembly of First Nations 2015). Following years of advocacy by Indigenous Leadership Initiative and partners, in 2021, the Government of Canada announced $340 million in new funding over five years to support Indigenous-led conservation and stewardship, including $173 million for Guardians programs (

Indigenous Leadership Initiative 2022). In December 2022, at the COP15 Biodiversity Summit, the First Nations National Guardians Network launched with additional federal funding (

Canada 2022).

Guardians have been referred to as the “eyes and ears” of the land and waters, continuing long traditions of stewardship through environmental monitoring, management planning, and enforcement of Indigenous law (

Kirby et al. 2018). Indigenous nations and communities are increasingly initiating Guardians programs to assert their rights and jurisdiction (with or without state recognition) (

Reed et al. 2021). Indigenous Guardians programs have been praised for their “weaving” of Indigenous and Western knowledge systems, which has been shown to contribute to the maintenance of ecological and cultural integrity (

Popp et al. 2020). Like Wahkohtowin's Guardians initiative, many Guardians programs focus on youth empowerment, while facilitating knowledge and language revitalization through elder-youth knowledge sharing and “[preparing] young people to become the next generation of educators, ministers and leaders” (

Indigenous Leadership Initiative 2022). Research has demonstrated a high social return on investment from Guardians programs; for instance, in the Northwest Territories, an estimated $2.50 in value was created for every dollar invested (

Kinley 2016).

Indigenous leaders and scholars have affirmed the complementarity of Guardians programs and NCS (

Townsend and Craig 2020). In addition to implementing the stewardship work involved in NCS (e.g., ecological conservation, restoration, etc.), Director of ILI, Valérie Courtois, spoke to the potential for Guardians to lead in monitoring, evaluation, and ground-truthing: “I would love to see that the Guardians be the ones…making sure that the large-scale [NCS] models that are being developed…are well ground-tested, and have genuine good inputs” (

Townsend and Craig 2020, p. 48). As we explore in subsequent sections, more explicit integration of Guardians and NCS may also be conducive to centering Indigenous knowledge and community priorities in planning and implementation, with potential benefits ranging from biodiversity conservation to youth empowerment. In turn, NCS may provide revenue to support the continued success and expansion of Indigenous Guardians programs (

Townsend and Craig 2020). Courtois emphasized the need for a diversity of funding streams for Guardians programs, highlighting that “in some cases, the carbon market could be as important, if not more [than government sources], for that core funding” (

Townsend and Craig 2020, p. 48).

Wahkohtowin is already working toward this possibility. As part of a broader vision for an Indigenous-led conservation economy, Wahkohtowin is making strides towards integrative, community-driven NCS while empowering youth as future climate action leaders through its Guardians program. Wahkohtowin was established by the Northeast Superior Regional Chiefs Forum to create and leverage opportunities for its owner, the First Nations in the Northeast Superior region of what is now known as Ontario, in Treaty 9 Territory (see

Fig. 1).

The Cree word wahkohtowin refers to kinship and connectedness amongst all relations, which reflects the organization's vision to support its communities in achieving sustainability and harmony within their traditional territories through regional collaboration. With direction from its owner First Nations, Wahkohtowin is advancing a range of local and regional initiatives to elevate Indigenous leadership within forestry, conservation, and climate action. Wahkohtowin has played a key role in negotiating forest tenure for an enhanced Sustainable Forest Licence and has established business partnerships for forest harvesting services. Other ongoing initiatives include a Herbicide Alternatives Program, a Moose Recovery and Monitoring Program, and a Tree-to-Home Program (localizing supply chains and enabling affordable homes), along with the Guardians Program.

Wahkohtowin's work is guided by the principles of the Northeast Superior Chiefs Forum, which include the understanding that “development comes from within”, “healing is a necessary part of development”, and “authentic development is culturally-based” (

Northeast Superior Regional Chiefs Forum 2012). These principles are reflected in the approach of the Guardians program, which emphasizes culture, personal development, and leadership skills among youth. The Guardians program engages youth in working with Elders and other Knowledge Holders to learn about traditional teachings, conducting vegetation index surveys, supporting moose monitoring, building solar thermal collectors, facilitating community engagement, and more.

Building upon these initiatives, Wahkohtowin is taking significant steps to advance climate action, namely through NCS. To date, Wahkohtowin has partnered with Forsite Forest Management Consultants to quantify potential greenhouse gas emissions reductions through Improved Forest Management activities in the Missinaibi Forest (Enhanced Sustainable Forest License). For Wahkohtowin, NCS presents an opportunity to contribute to a safe climate for future generations while building a conservation economy and strengthening Indigenous leadership in forest management planning. Wahkohtowin's vision for a “conservation economy” dates back nearly ten years, reflecting the vision of the Northeast Superior Regional Chiefs Forum for “a deliberately reorganized economy” with desired outcomes that include “good work, strong cultures, and healthy ecologies” (as documented in a 2014 report commissioned by the Northeast Superior Regional Chiefs Forum from EcoTrust Canada (

EcoTrust Canada 2014, p. 2)). Today, Wahkohtowin is pursuing NCS as a key enabling element of a broader conservation economy, generating revenue that can be reinvested in related initiatives and biocultural aims.

The envisioned forest carbon management project will align with and support further development of the Guardians program. The 2022 Climate Action Initiative workshop series was an initial step toward integrating climate action, including NCS, into the Guardians program. As a catalyst for the next generation of community leaders, the Guardians program is an important vessel for generating awareness, capacity, and interest in climate action and the opportunity for NCS envisioned by Wahkohtowin and community leadership. The workshop series with Wahkohtowin's Guardians began to generate this awareness and interest while initiating dialogue on core questions. Namely, what possibilities arise when NCS are driven by Indigenous guardianship, guided by Indigenous knowledge and multifaceted community priorities?

Doing and learning the Wahkohtowin way

Having contextualized the aims and endeavours of Wahkohtowin within the broader, emergent movements of NCS and Indigenous Guardians, in this section we outline the approach that guided the Wahkohtowin Guardians Climate Action Initiative, including key aspects of the facilitation process, activities, and outputs of the initiative.

Indigenous activists and scholars have long called for decolonizing approaches to research rooted in respectful relationships (

Tuhiwai Smith 1999). Too often, communities have been subject to exploitative research that perpetuates ethnographic assumptions and devalues Indigenous ways of knowing (

Tuhiwai Smith 1999). Decolonizing scholarship calls for the valorization of Indigenous knowledge and co-production with knowledge holders (

Tuhiwai Smith 1999;

Menzies 2001;

Stanton 2014;

Sandoval et al. 2016;

de Leeuw and Hunt 2018). Moreover, advocates emphasize that cross-cultural research should be guided by the self-identified priorities of an Indigenous research partner or community (

Tuhiwai Smith 1999).

Consistent with the above, the idea for and approach to the Guardians Climate Action Initiative and workshop series emerged over months of discussion between David Flood, RFP (General Manager of Wahkohtowin), Tammy Tremblay (former Wahkohtowin Environmental Initiatives Lead), Amberly Quakegesic (former Guardian Program Manager), Lara Powell (University of Guelph M.A. candidate), and Ben Bradshaw (University of Guelph Professor). Through an iterative planning process, an approach was established that the Wahkohtowin team deemed contextually appropriate and practically useful, aligned with the broader mandate for serving Wahkohtowin's owner First Nations. Broadly, the Guardians Climate Action Initiative contributed to Wahkohtowin's mandate to drive action on climate change and support a sustainable future, as directed by the Chiefs of the Northeast Superior Regional Chiefs Forum.

Though borne of a research partnership with a university, we refer to “the initiative” rather than the “research project” herein to reflect our approach, which was primarily pragmatic rather than academic. While the workshop series generated scholarly contributions (which we present in this manuscript), the primary goal was to generate a positive learning experience for the youth participants, in line with the broader mission of the Guardians program. For example, Wahkohtowin leadership emphasized the limitations of surveys and interviews for addressing the topic of climate change and NCS, particularly when working with youth. Instead, a learning-oriented approach was adopted, given our unfamiliarity with the emergent subject matter; our approach sought to build understanding and establish common ground. Further, we encouraged the Guardians to partake as active partners in sharing knowledge and perspectives and in designing creative outputs to spark dialogue and action amongst their communities. Ultimately, it was an emergent, imperfect process that generated both best practices and hindsight lessons and continues to be improved upon as Wahkohtowin integrates the Climate Action Initiative as a part of the Guardians’ annual programming.

We iterated an approach oriented around learning, creative communication, and youth empowerment. We began with a bundle-building

4 workshop focused on

miyo pimatisiiwin (a Cree concept of “living the good life”, loosely), the Medicine Wheel, and leadership capacity-building. We started with bundle-building in alignment with the broader mission of the Guardians program to build youth's metaphorical bundle of teachings, supporting resilience and personal development. Bundle-building remained an underlying aim throughout the Climate Action Initiative, which facilitated learning and discussion about climate action within a context of cultural teachings, values, and relationships with the land.

The approach sought to interweave Indigenous and Western knowledge systems, as cultural maintenance is a broader aim of the Guardians program and is critical to building capacity for community-driven NCS. Throughout the workshop series, with the help of Elders and guest speakers, the facilitators highlighted the critical role of Indigenous knowledge in environmental stewardship and climate action, having been developed over millennia and bolstered by core values of respect, responsibility, and reciprocity (

Bell 2013). Cultural traditions and knowledge were emphasized both in the workshop design and in the themes of discussion that unfolded. We were privileged to have Elder Sandra Ruffo lead the opening and closing prayers, share rich perspectives from her experience as a student support worker, and ground our discussions in cultural teachings. In addition, a representative of Indigenous Climate Action facilitated a session on Indigenous leadership in climate action, addressing the ways in which ancestral teachings serve as the roots of wellness, resilience, and capacity for climate action leadership.

In total, six youth Guardians took part in the Climate Action Initiative, as well as one youth working for a local Lands and Resources Department. The primary facilitators were Quakegesic and Powell (co-authors), as well as Wahkohtowin's former Environmental Initiatives Lead Tammy Tremblay. McCulloch (co-author) took part as a Guardian and a co-facilitator of some sessions. The Guardians ranged in age from 15 to 28, including one self-identifying young man and the remainder self-identifying women, five of whom were members of Wahkohtowin's owner First Nations and one a member of a non-owner First Nation.

From February to March 2022, the Climate Action Guardians participated in weekly, remote workshops over an 8-week period. The first half of the workshop series focused on learning and discussion on climate action and forest stewardship. The first two sessions were facilitated with support from EcoTrust Canada, utilizing a “Community Carbon Toolkit” developed by Wahkohtowin with support from EcoTrust Canada to aid community engagement and raise awareness on the topic of NCS. The workshops addressed climate science, forests and climate mitigation, regional climate change impacts and adaptation planning,

5 relevant cultural teachings, relationships to the land, and effective ways to communicate about climate change. Considering the prevalence of climate anxiety, particularly amongst youth (

Thompson 2021), we strived for empowering rather than demoralizing conversations; for instance, we highlighted climate mitigation actions that individuals can support and examples of community- and Indigenous-led action. The remote workshops included some presentations but primarily prioritized interactive learning through group discussion and breakout sessions with opportunities for verbal, written, and other creative forms of expression.

In addition to learning and reflection, through the Climate Action Initiative, the Guardians co-created youth-led outputs through semi-structured discussions and collaborative digital tools. The group co-directed and produced a film in which each Guardian spoke to the question: “why is climate action important to you?”. The Guardians then collectively planned and facilitated a final public webinar

6 in March 2022, which consisted of a screening of the film, as well as two panel discussions, one amongst the Guardians and one in which the Guardians posed questions to relevant local stakeholders and knowledge holders.

The facilitators encouraged the Guardians to take ownership of the process; for instance, using Google “Jamboards”, Zoom “breakout rooms”, and other tools, we facilitated brainstorming sessions to collaboratively plan the film and webinar (e.g., discussing the key points to convey in the film, the webinar flow, potential panelists, panel questions, roles, etc.). Using “Jamboards”, Guardians could share their thoughts using “sticky notes” and text, which some preferred over verbal discussion; such tools also enabled us to identify themes, aligned/divergent perspectives, and anonymously indicate preferences with “stickers” and other tools. Guardians stepped into various leadership roles throughout the process (such as film editing, which was taken on by Ryan Wesley).

We prioritized the experience and agency of the Guardians, including within data governance; for instance, we sought out a balance between honouring participants’ perspectives by recording direct quotations and respecting the wishes of one participant who expressed discomfort at the prospect of recording Zoom workshops.

7 The research was approved by the University of Guelph Research Ethics Board (REB# 18-12-016) and adhered to relevant ethics guidelines.

The workshops were conducted remotely, differentiating the approach from typical Guardian programming that takes place on-the-ground in the community. The remote format allowed us to avoid pandemic-related restrictions while enabling participation from off-reserve youth, such as university students. Participants joined remotely from Chapleau, Sault Ste Marie, Sudbury, North Bay, Guelph, and London, Ontario. Two participants were subsequently hired on as seasonal (land-based) Guardians after the Climate Action Initiative, and two participants had previously worked as land-based Guardians; however, most of the group had not previously participated in in-person Guardian programming. As such, the Guardians’ perspectives discussed herein don't necessarily reflect the typical Indigenous Guardian (though there may not be a “typical” Guardian given the diversity of programming across the country); nonetheless, the initiative raised relevant insights with respect to Guardians, NCS, and youth perspectives. As Wahkohtowin's Guardian program grows and evolves, the team aims to strengthen retainment and continuity from one season to the next.

We sought to promote the replicability of the Climate Action Initiative by recording the process and tools that were used and documenting both successes and hindsight lessons. These lessons have fed into a 2023 iteration of the initiative with an improved approach—in particular, strengthened by more Indigenous guest speakers, including other youth Guardians and session topics like cultural burning (

Hoffman et al. 2022), Indigenous food sovereignty (

Coté 2016) and Two-Eyed Seeing (

Marshall 2004).

Outcomes and discussion

In this section, we summarize key themes that emerged in the workshops and offer an analysis of transferable insights relating to Indigenous-led NCS, Guardians, and climate action more broadly, in reference to contemporary scholarship. We present and extend observations relating to the value of Indigenous knowledge in thinking about climate change and implementing NCS, highlighting the significance of holistic, ethically-informed knowledge systems. Subsequently, we discuss the Guardians’ insights regarding the role of youth in climate action, and, building upon their assertions, we offer our own analysis of youth, Guardians, and implications with respect to NCS. Finally, we discuss pathways for interweaving knowledge systems and decolonized cross-cultural collaboration.

Indigenous knowledge and the value of a holistic approach

Throughout the workshop series, a key thread of discussion was the value of Indigenous knowledge in thinking about and acting on climate change—especially in terms of a holistic approach that encompasses interconnected social-ecological and cultural factors. The Guardians had varying levels of awareness of cultural teachings, and most had spent much of their lives living away from their traditional territory. Some frequently spoke of traditional teachings with ease and familiarity, and Guardians who previously participated in Wahkohtowin's land-based, seasonal Guardians program referenced cultural teachings gained through that experience. Others expressed that they were beginning to discover their culture for the first time, having not participated in the Guardian program nor having had much opportunity to build their cultural bundle through other means. Nonetheless, cultural themes were apparent, and all were eager to learn.

The group collectively observed that Indigenous knowledge and value systems hold particular importance in the context of the global climate crisis. Chiefly, the discussions reflected an expansive view of “climate action” rooted in Anishinaabe and Cree teachings of the interconnectedness of all things. As one Guardian shared:

“We have to remember who we are and how the Earth helps us holistically, so mentally, emotionally, spiritually, physically…with everything and we have to make sure that we take care of it”.

From the outset of the workshop series, conversations expanded to encompass a wide range of issues, and Guardians extended session topics to intersecting social, ecological, and cultural factors. Guardians shared concerns and insights regarding impacts on animals and their habitats, medicines and culturally significant species, biodiversity, hunting, food sovereignty, potable water access, air quality, personal and community wellness and healing, mental health, economic impacts, and more. Both implicitly and explicitly, the group spoke of the ways in which everything is connected and that climate change cannot be addressed in isolation from interrelated social, ecological, and spiritual factors.

For instance, in the first session, the issue of climate “tipping points”

8 was introduced through the Community Carbon Toolkit. One Guardian extended the concept beyond the standard scientific application of the term to propose that many communities are faced with social or cultural tipping points. They posited that, as younger generations lose touch with traditional teachings and spend progressively less time in their traditional territory, the land is increasingly at risk of exploitation and degradation. Thus, a tipping point may exist at which a healthy environment is no longer recoverable, and this, in turn, would impair the ability of future generations to maintain their culture and relationship with the land.

9Similarly, other Guardians extended climate impacts to concerns regarding culture and community and provide an opportunity for climate action to bring positive outcomes in these areas. In one Guardian's words, “Protecting and healing the lands, waters and resources I feel will bring back a sense of unity and community healing that have been lost in some communities”. The holistic take on “climate action” that emerged is eloquently captured in the following reflection from Brie Nemeth, one of the Guardians:

“We need to honour [Mother Earth] in all of her beauty and sacredness. All of the winged, the crawlers, the four-legged, we're all connected. If the earth is not healthy then we can truly not be healthy either”.

This concept of interconnectedness and the broader “holistic” theme of discussion raised by the Guardians aligns with many Indigenous knowledge systems, as widely documented in the literature. Broadly, Indigenous knowledges acknowledge the interconnectedness of all things and are not limited by the fragmented tendencies of Western science (

Battiste and Henderson 2000;

Levac et al. 2018). Of course, Indigenous knowledges are highly varied and often uniquely place-based (

Aikenhead 2011). Some argue that the generic characterization of Indigenous knowledge as “holistic” and scientific ecological knowledge as “mechanistic” is an overly simplistic explanation (

Ludwig and Poliseli 2018). Nonetheless, it is widely acknowledged that “holism” or a holistic framing is a core, common thread of Indigenous ways of knowing that differentiates such worldviews from the often reductionist, positivist approach of Western science (

Berkes and Berkes 2009;

Levac et al. 2018;

Mobley et al. 2020).

This is certainly true of the Anishinaabe and Cree

10 teachings of interconnectedness that inform Wahkohtowin's approach; in fact, this is embedded in the Cree term and concept

wahkohtowin, which represents kinship and connectedness and speaks to the extension of oneself to the land, air, water, animals, and spirit. The concept of

wahkohtowin is intrinsic to Cree Natural Law, which Cree Elders have advocated as having great value in contemporary society, further reinforcing the points raised in our workshop discussions (

Voices of the Land 2017).

Building upon the Guardians’ insights and our literature review, we can turn to Wahkohtowin's programming for an applied example of holistic NCS. An underlying understanding of interconnectedness is reflected in the organization's programs, which do not address any single issue in isolation. For instance, Moose Recovery and Herbicide Alternatives are two high priority initiatives that are closely related. Seeking to address both concerns with one proposal, Wahkohtowin requested a one-hundred-meter-wide no-herbicide buffer around all Late Winter Moose Habitat on behalf of its owner First Nations. While the primary aim of the proposal was to protect feeding habitat in close proximity to shelter for moose in winter, it would simultaneously reduce the total area of the forest being sprayed with herbicide, and generally protect biodiversity, while creating more potential for novel Herbicide Alternatives. Relatedly, Wahkohtowin is involved in a project assessing the inoculation of seedlings with mycorrhizal fungus as a strategy to support growth and survival of planted trees without herbicide. If herbicides were banned within 100 m of Late Winter Moose Habitat, it would create more opportunity and incentive to plant inoculated seedlings, which have an increased growth rate and thus increased carbon sequestration, making this proposal a potential NSC as well. This 100 m buffer proposal exists within the spheres of Herbicide Alternatives, Moose Recovery, and NCS, and is one example of a holistic initiative being pursued by Wahkohtowin and their owner First Nations.

Such concepts of interconnectedness differentiate Indigenous knowledges as relational and non-dualistic, in contrast with anthropocentric Western discourses that position humanity as separate from nature and at the center of creation (

Wildcat 2009;

Kimmerer 2013). In this sense, complementary to the themes raised by the Wahkohtowin Guardians, Indigenous scholars and knowledge keepers highlight the value of Indigenous knowledge in combatting ecological and climate crises, suggesting a need for a paradigm shift in the way we approach such challenges (

Wildcat 2009;

Whyte 2017;

Cameron et al. 2021). The value of holistic, relational Indigenous ontologies is reflected in the millennia-long track record of Indigenous Peoples’ environmental stewardship around the world (

Schuster et al. 2019). Given the intrinsic interconnections between the global climate and ecological crises (

Farber 2015;

Corlett 2020), there is much to be learned from the Guardians’ insights, which not only resonate within the context of NCS but are also reinforcing other calls for decolonizing and integrative approaches to societal challenges (e.g.,

Sterling et al. 2017;

McGregor 2018;

Galway et al. 2022). As Guardians programs are already applying traditional ecological knowledge within land stewardship toward multifaceted aims, they may offer a natural vehicle for championing holistic approaches to NCS guided by Indigenous knowledge.

Ethical ontologies for climate action

Throughout the workshop series, values and ethics were central to the Guardians’ discussions, including traditional teachings around respect, responsibility, and reciprocity, Seven Generations Thinking, and “being accountable to and giving back to the land”. Some of the Guardians brought forward spiritual elements, such as the understanding that “everything has a spirit and different purposes, like how Tamarack trees are for healing, strength and guidance”, as Guardian Brie Nemeth shared. While not every Guardian spoke of spirituality, values and ethics were prominent throughout, and all agreed that humanity has a shared, collective responsibility to take action on climate change.

The ethical and moral themes raised by the Guardians align with Indigenous ways of knowing regarding collective responsibility and relationships to the land. Whereas Western knowledge systems focus on objectivity, Indigenous knowledge systems tend to be rooted in values and ethics (

Levac et al. 2018). This again relates to “holism”, in that knowledge is understood to be derived from multiple sources (from all living beings and the realms of the mind, the heart, the body, and the soul) and rooted in moral ethos (

Kovach 2021). According to

McGregor (2004), Indigenous knowledge is “about being in relationship with Creation; it is about realizing one's vision and purpose and assuming responsibilities accordingly” (p. 391). Built on values of respect, relationship, reciprocity, and responsibility, Indigenous knowledge offers critical insights for the discourse and practice of environmental sustainability and climate action (

Bell 2013;

Menzies et al. 2022). As McCulloch (co-author and participant) shared:

“Responsibility is a more powerful concept than law. Laws are rules that are created and enforced by a legal system while responsibility is understood inherently. That may partly explain why we see so many youth involved in climate action and activism because we automatically understand responsibility and fairness at an early age… we can all take climate action by practicing responsibility to our Mother Earth, to future generations and to all our relatives both human and otherwise and by looking to youth who have not yet been forced to lose or forget this inherent understanding of responsibility to the planet”.

As raised in the workshop discussions and supported by the literature, the moral underpinnings of Indigenous knowledge offer much value in addressing the dual ecological and climate crises. In contrast to the technocratic fixes emphasized in Western knowledge systems,

ethical knowledge may yet prove a better guide for facing today's social-ecological challenges (

Mulrennan 2020). Climate justice scholars highlight the ways in which racial and geopolitical power imbalances are obscured in climate decision-making that focuses on science and technology without consideration for the fact that Indigenous Peoples are some of the most affected by, yet least responsible for, climate change (

Williams 2012). While climate justice and related fields are making strides for justice-informed climate action, the social sciences are severely undervalued; between 1990 and 2018, the natural and technical sciences received 770% more funding than the social sciences for research on issues related to climate change (Overland and Sovacool 2020, cited in

Deranger et al. 2022).

Moreover, beyond that which the social sciences offer, climate responses urgently require a moral framework—solutions grounded in solidarity and accountability to future generations. Western science approaches have certainly generated critical contributions to climate mitigation efforts; yet, without popular and political will, uptake and implementation remain dangerously slow.

11 In addition to a proven track record built on thousands of years of observations and holistic worldviews, the

moral foundations of Indigenous ontologies hold evident value in the context of the climate emergency, and yet remain vastly underrepresented in the dominant discourse (

Kovach 2021;

Menzies et al. 2022). Thus, broadly, there is a need to decolonize climate research and policy and to begin positioning Indigenous knowledge and worldviews as a foundational framework for climate action (

Deranger et al. 2022;

Menzies et al. 2022). More specifically, the ethical frameworks that bolster and differentiate Indigenous knowledge speak, again, to the potentially transformative opportunities presented by NCS if guided by Indigenous knowledge and guardianship.

The role of youth

The Guardians discussed the importance of youth involvement and leadership in climate action, both broadly and specifically within NCS as land stewards. One common reflection was that youth come with a “fresh slate”, making them generally more open-minded and often more capable of imagining a different reality or a different future. One Guardian shared that “when youth get involved in situations that need change, I believe that more people are willing to kind of have an open mind because the youth are going to them about it”. Indeed, this observation aligns with various Anishinaabe teachings and beliefs that speak to the role of young people in bringing new knowledge to the people (

McGregor 2004). Another prominent thread of discussion regarding the role of youth was that they will be the ones affected by the decisions made today regarding climate action. As one Guardian put it, “they are our future,

we are the future”. The group was also forthcoming regarding personal anxieties about the future in light of climate change. In the webinar, one Guardian shared that, “at this point I really don't know what my future is going to look like and I really don't know what my child's future is going to look like and my grandchildren and it's a pretty scary thought”.

Such comments point to the importance of engaging youth as those who will be most affected by climate inaction/action; conversely, the Guardians’ reflections highlight the injustice of inaction for future generations and the risk of deferring burden to those least responsible for climate change. As emphasized by the Wahkohtowin Climate Action Guardians, youth participation, if not leadership, is imperative from the perspective of empowering the next generation of leaders; giving voice to those who will be most affected; and generating fresh, transformative perspectives marked by the inherent understanding of responsibility that is often lost among adults. Yet, as the Guardians highlighted, narratives around youth leadership can become problematic when people in power turn to young people for hope without taking adequate action to safeguard their futures. Rather than focusing on the age of youth activists or the hope that their activism inspires, decision-makers would do better to engage with the substance of the arguments put forth by young people for climate action (

Hess 2021). Youth-led climate action is best supported by an understanding of collective responsibility. As the Guardians emphasized, we all have a role to play in ensuring a healthy planet for future generations.

The Guardians’ reflections also speak to the importance of platforms for uplifting youth voices on climate action, spaces for connection and sharing, and the potential for Guardians programs to strengthen young people's relationships with Mother Earth. For instance, speaking to her experience as Guardian Program Manager, co-author Amberly Quakegesic highlighted that:

“We come from the land and feeling that connection is instrumental in wanting to treat the land with respect. For me, working with the Guardians program I get to do a lot of projects that are land-based that have strengthened my relationship with Mother Earth and it only makes me want to get to know her more. And I just hope that other young people get to have these experiences as well…and grow that relationship”.

Similarly, Elder Sandra Ruffo shared that connection to land and culture are critical remedies for climate anxiety, relating an experience of speaking with a young student:

“…we were talking about what's going on in the world today and she was like, “I don't even want to be here in 30 years…I hope I'm gone" she said, “the world is going to end”. I said, the world's not going to end, the world's going to end as you know it today…we are going to go back to the beginning again, to learn how to take care of ourselves, to learn how to take care of the land, to make sure that our Mother Earth prospers…go back to the old teachings, go back to the kindness we're supposed to have as Indigenous Peoples and show people that we have so much knowledge to teach them, that we are survivors, we are warriors”.

Guardians programs are already doing this important work of reconnection, reclamation, and empowerment; explicit involvement in NCS may further expand the potential for Guardians programs to empower Indigenous people, especially youth, to be involved in solutions to what can otherwise feel like an insurmountable and disempowering challenge.

In terms of co-creating spaces for sharing and discussion, the Guardians Climate Action Initiative itself served as an ideal vehicle for addressing climate anxiety and re-centering culture, community, and optimism. On several occasions, Guardians (and facilitators) expressed that the conversations brought a sense of hope and purpose. While discussions regarding climate change can be a source of anxiety, particularly among youth (

Thompson 2021), the workshop series instead brought a sense of comradery and optimism by bringing together like-minded young people driven to contribute to a better world. Several Guardians expressed that it was reassuring simply to know that there are others who share similar hopes and concerns and inspiring to connect with others who are similarly motivated to act on climate change, learn from traditional teachings, and build relationships with the land. This speaks, again, to the broader value of Guardians programs (particularly youth-focused programs) and the opportunity for integrating climate action into such programs.

Wahkohtowin's vision for Indigenous-led NCS—that is culturally aligned and that integrates Indigenous knowledge—requires leadership from community members who have cultivated strong relationships with land and culture. In this sense, the Guardians program is already indirectly building capacity for NCS by strengthening youth's connection to their traditional territory and cultural teachings. Beyond carbon management, NCS, facilitated by Guardians, has the potential to promote empowerment, cultural revitalization, and healing. These impacts were powerfully communicated by Dahti Tsetso, Deputy Director of Indigenous Leadership Initiative, in a reflection on the First National Guardians Gathering 2021: “As we listened to Guardians talk about their connection to the land and the pride they feel in Indigenous culture and knowledge, it felt like reclamation—like we are taking back what [residential] schools tried to rob from us” (

Indigenous Leadership Initiative 2021). Not only is cultural maintenance needed to ensure its continued application in forest management planning and NCS, but in a broader sense, strong relationships to culture, identity, and the land can play a key role in collective healing, cultural resurgence, and resilience into the future (

Indigenous Leadership Initiative 2021).

Two-eyed seeing and decolonizing NCS

The workshop series with the Guardians generated discussion and insights around knowledge co-production and collaboration. Related to the above theme of collective responsibility, the Guardians recognized value in cross-cultural collaboration and knowledge sharing. For instance, one Guardian, Brie Nemeth, posed the question of how to extend Indigenous ways of knowing to others:

“As Indigenous people we know that everything has a spirit and we have that respect, for the most part anyway…how do we get it out to the general population…for them to also understand that concept and have that same respect?”

Another Guardian, Ryan Wesley, shared a vision for a future in which we “get past all of the differences that we have as humans and realize that…we all have the same home and that we need to fix it”. Similar comments continued to arise around collective responsibility and the importance of unity and collaboration in responding to the climate crisis. While Indigenous Knowledge was explicitly addressed by the facilitators throughout the workshop series, it was the Guardians’ response and interest that led to a more specific discussion of frameworks for interweaving the strengths of Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing with Western science, namely Two-Eyed Seeing (

Marshall 2004).

Building on this discussion, the literature review and analysis by the research team further support the case that a Two-Eyed Seeing approach guided by holistic traditional teachings can unlock the wide-reaching ecological, social, and economic opportunity of Indigenous-led NCS. In practice, Two-Eyed Seeing is growing within Indigenous Guardians programs, as Guardians leverage the strength of multiple knowledge systems to care for the land while promoting cultural preservation (

Popp et al. 2020). Guardians are thus well positioned to implement Two-Eyed Seeing within NCS at the community level, which in turn may facilitate more community-centered and holistic design, monitoring, and evaluation. For instance, Wahkohtowin's Guardians are currently interviewing Knowledge Holders and mapping community values to be prioritized within landscape-level forest management planning; this information will subsequently feed into NCS planning, including in determining which areas to prioritize for protection (which is a component of the envisioned plan to increase carbon sequestration). Applying Two-Eyed Seeing, Guardians may also support holistic, ecosystem-wide interpretation of climate change impacts, which is an identified priority among First Nations in the region (

Menzies et al. 2022).

Two-Eyed Seeing requires moving beyond the dichotomous discourse in which Indigenous knowledge is positioned as a plug-in to existing Western frameworks (

Bartlett et al. 2012;

Levac et al. 2018). Notably,

Deranger et al. (2022) assert, “no longer can we afford to simply `tweak the system' by slotting into mainstream processes those elements of Indigenous world view that seem to `fit' most comfortably”. A decolonizing approach is needed that attends to the power differential between Indigenous and Western knowledge systems and centres the latter while also recognizing the plurality that exists across and within Indigenous knowledges (

Bartlett et al. 2012;

de Leeuw and Hunt 2018;

Levac et al. 2018). Furthermore, proponents must take care to promote Indigenous self-identified views of traditional ecological knowledge as opposed to Eurocentric views, as well as avoid knowledge appropriation (

McGregor 2004).

Relatedly, decolonial scholarship resonates with the earlier points from the Wahkohtowin Guardians regarding the risk of deferring the burden of climate action to those who have, in fact, done the least to cause it. Like the risks that arise when older generations turn to the next generation for hope and solutions (

Hess 2021), when it comes to promoting Indigenous-led NCS, non-Indigenous parties must also be mindful of offloading the burden of responsibility. As was discussed in the workshop series with the Guardians, whereas Indigenous Peoples are disproportionately impacted by climate change (

Williams 2012), colonialism is considered a root cause of climate change amongst many Indigenous and critical scholars, having entrenched dualistic, extractive, and exploitative relationships between people and the earth (

Wildcat 2009;

Whyte 2017;

Stein 2019).

Indigenous Climate Action (2021) highlights that solutions must address the ongoing drivers and root causes of climate change embedded in capitalism, as well as prioritize Indigenous rights. With this in mind, a decolonizing lens for NCS requires that support for Indigenous leadership be accompanied by adequate resources and supportive of local priorities, and advanced in conjunction with efforts to hold both the Settler state and polluting industries accountable.

Finally, while Indigenous rights were not always a primary and explicit focus of the workshop discussions (nor is it within the scope of this paper to address the legal context

12 of NCS in detail), the issue of rights is fundamental to “decolonizing NCS”. Above all other rationales, Indigenous participation and leadership in NCS are critical from the perspective of upholding the inherent treaty and constitutional rights of Indigenous Peoples within their traditional territories, as affirmed by the Canadian Constitution Act and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Thus, as

Artelle et al. (2019) emphasize, supporting resurgent Indigenous governance “ought not be simply a means to an end for conservationists” (p. 6).

Conclusions

In this article, we explored the opportunity for NCS rooted in Indigenous guardianship, extending insights from the approach and outcomes of Wahkohtowin's 2022 youth-led Climate Action Initiative. In sum, Indigenous Guardians programs—guided by Indigenous knowledge and holistic, community-centered aims—present a pathway to NCS with benefits including and beyond climate change mitigation. Indigenous leadership in NCS is critical from a rights perspective and must not be viewed as a means to an end; nonetheless, our analysis reinforces that Indigenous leadership and substantive engagement with Indigenous knowledge can also ensure successful outcomes and multiple benefits for communities, ecosystems, climate action, and reconciliation.

The initiative with Wahkohtowin's Guardians aimed to engage youth in peer-to-peer dialogue on climate action, including NCS, and provided a platform for the Guardians to express their perspectives and raise awareness amongst their communities. The discussions generated transferable insights on key themes relating to Indigenous knowledge and holistic approaches to NCS, values and ethics, the role of youth in climate action, and cross-cultural collaboration.

Drawing on the Guardians’ insights, we discussed the opportunity for climate action, and specifically NCS, driven by the holistic and ethical framework that broadly differentiates Indigenous from Western knowledge systems. First, we discussed the value of holistic approaches and Indigenous knowledge in thinking about and acting on climate action. The Guardians identified interconnections between climate action, cultural resilience, youth mental health, biodiversity and the health of non-human relatives, explicitly and implicitly referencing Indigenous knowledge and cultural teachings. Extending these insights—in conversation with the literature and applied examples from Wahkohtowin—we discussed the value of rooting NCS in holistic, Indigenous-led approaches in conjunction with Guardians programs. Rather than a myopic focus on carbon management and lip service to social and ecological “co-benefits”, there is a need for a holistic approach to NCS to address multiple, intersecting challenges.

Building on this analysis, we explored how the moral principles embedded in Indigenous knowledge systems can support transformative outcomes at the intersection of climate action, NCS, and Indigenous guardianship. Values and ethics were central throughout the workshop discussions, and the Guardians often referenced teachings of respect, collective responsibility, and reciprocity when discussing climate action and land stewardship. The discussions highlighted that the global climate emergency demands more than technical fixes and objective science; solutions exist but require political will, climate justice, and long-term thinking, driven by a moral imperative of collective responsibility to future generations. Thus, building upon the Guardians’ wisdom, we posit that NCS is best advanced through an approach guided by the holistic, ethical underpinnings of Indigenous ontologies, rooted in values of respect, responsibility, and reciprocity.

Relatedly, we highlighted how the workshop discussions underscored the importance of youth involvement and leadership in climate action, broadly and specifically within NCS as Guardians programs. We presented Guardians’ insights regarding opportunities for youth leadership and the moral imperative of including youth in decisions and actions that will affect their future. Extending the Guardians’ reflections, we discussed how youth engagement in NCS via Guardians programs can strengthen relationships with the land and community and foster empowerment in the face of daunting challenges.

Finally, the workshops generated insights regarding knowledge co-production, collaboration, and decolonizing NCS. We discussed Guardians’ reflections on cross-cultural collaboration and knowledge sharing, reinforced with reference to the literature. Ultimately, we suggest that a holistic, decolonizing approach to NCS is best achieved through a Two-Eyed Seeing lens that centres, rather than appropriates or assimilates, Indigenous knowledge. Guardians programs are well-positioned to implement said approach to realize the full potential of Indigenous-led NCS.

While still in its early phases, Wahkohtowin's approach offers one example of an effort to integrate Guardian programming within a holistic vision for NCS. The Climate Action Initiative discussed herein was one initial step to rooting NCS in guardianship, beginning with learning, capacity building, and youth engagement. Following the workshop series, one participant took on a subsequent role with Wahkohtowin's Guardian “re-measurement crew”, supporting field-based monitoring for an NCS pilot project that utilizes mycorrhizal fungi-tree relationships to increase tree growth, survival, and carbon sequestration. Concurrently, Wahkohtowin Guardians have been supporting field inventories, biodiversity baselines, monitoring, and interviewing Knowledge Holders as part of a project called “Nisto Watapi—Rooting our Community's Capacity Toward Nature Based Climate Solutions”. Wahkohtowin is also pursuing market-based NCS opportunities as a pathway to diversify revenue streams and enable long-term sustained funding, including for Guardian roles. Learning and capacity building will also remain a priority, including through the Guardians Climate Action Initiative, which is being refined and integrated into annual programming.

Broadly, Guardians are already facilitating the important work of maintaining and implementing traditional ecological knowledge through NCS, though without recognition for carbon management as such. Within NCS initiatives, Guardians could benefit from long-term and diversified funding opportunities while providing the expertise and boots-on-the-ground needed for rigorous monitoring and evaluation of social-ecological and other outcomes beyond carbon, utilizing Two-Eyed Seeing. Moreover, Guardians could enable effective community engagement at all stages of the planning and implementation of NCS, to empower communities to be directly involved in the management of their ancestral homelands. Involving youth Guardians in NCS may prove especially beneficial in terms of involving those who will be most impacted by climate inaction/action and in terms of long-term, broader outcomes derived from cultural revitalization and capacity building.

To advance these opportunities, there is a need for direct resources for Indigenous leadership in NCS, both on the ground and at decision-making tables, as well as knowledge sharing and capacity building at the community level (which is being advanced by emerging groups such as the Restore, Assert and Defend (RAD) Network (

RAD Network, n.d.)). We have also identified a need for a broader conceptualization of “natural climate solutions” within the allocation of funding and support to recognize and prioritize pre-existing Indigenous-led initiatives that are implicitly advancing NCS, including Guardians, Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas, Indigenous cultural burning, and other forms of Indigenous-led land stewardship (e.g., avoided land conversation).

The cultural values, knowledge, and leadership capacity instilled by Guardians programs lend themselves to high-impact NCS, in tandem with broader Nation-building and community resilience. Ultimately, with Indigenous leadership, knowledge, and social-ecological priorities at the forefront, NCS presents a promising path for climate action and reconciliation.