Background

The Canadian Species at Risk Act (SARA) was enacted in 2002 and came into force in 2003 in response to Canada’s commitments to the 1992 United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. The purposes of the act are “to prevent wildlife species from being extirpated or becoming extinct, to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered, or threatened as a result of human activity and to manage species of special concern to prevent them from becoming endangered or threatened” (SARA Section 6). Implementation of the Act is the responsibility of the competent Ministers, the Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) Minister for terrestrial species and the Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Minister for aquatic species. Aquatic species are those defined by the federal Fisheries Act (Section 2): fishes, shellfishes, crustaceans, and marine animals. The DFO Minister makes listing recommendations for aquatic species to the ECCC Minister, who ultimately makes the listing decision for all species. At the time of its enactment, SARA was lauded as exemplary legislation for protecting endangered species. Its preamble mentioned many things that its American counterpart, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, lacked such as: “wildlife, in all its forms, has value in and of itself and is valued by Canadians for aesthetic, cultural, spiritual, recreational, educational, historical, economic, medical, ecological, and scientific reasons”; “the traditional knowledge of the aboriginal (sic) peoples of Canada should be considered in the assessment of which species may be at risk and in developing and implementing recovery measures”; “knowledge of wildlife species and ecosystems is critical to their conservation”; and “the habitat of species at risk is key to their conservation” (Species at Risk Act (2002), Preamble). There was also a major concern at the time that has since proved to be valid—species assessed as at risk of extinction were not automatically listed under SARA, unlike the American Endangered Species Act. However, after several previous iterations of SARA that had included automatic listing had died on the parliamentary table, it was likely naïve to believe that an act would be passed without Ministerial discretion included.

The SARA process

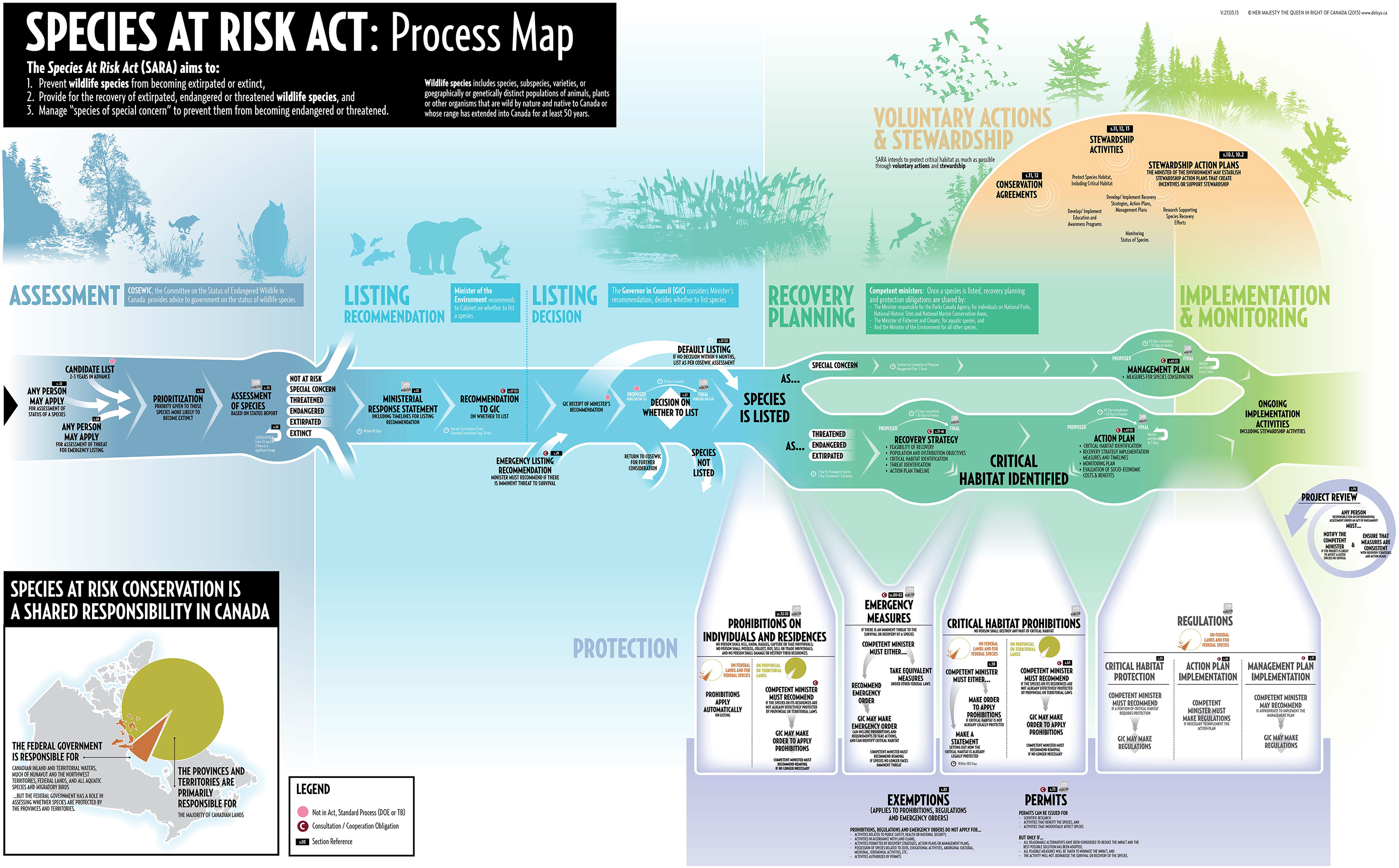

In 2001, I joined Fisheries and Oceans Canada as a research scientist and, later, Biodiversity Section head to develop and implement the aquatic species-at-risk science program for the Laurentian Great Lakes that covered all but the fourth of five steps in the SARA process (

Fig. 1). I also contributed to the development of national standards for the implementation of various aspects of SARA (e.g., listing decisions—

DFO 2009a; terminology—

Clark et al. 2010; critical habitat—

DFO 2009b;

Mandrak et al. 2014). I have written many COSEWIC reports and recovery potential assessments, and several recovery strategies. As a member of the Freshwater Fish Species Specialist Committee (SSC) of the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) since 2001 and, more recently, co-chair, I have spent a lot of time thinking about, and undertaking, conservation activities (

Fig. 1). Since moving to academia in 2013, I have continued to conduct research on each of the steps.

Based on my experiences, I reflect upon how successful the implementation of SARA has been at meeting its intended purposes through the implementation of the five-step SARA process (

Fig. 1), particularly as it relates to aquatic species at risk (SAR). I also reflect on the role of Indigenous knowledge across the entire SARA process. My reflections and associated recommendations are not meant to be comprehensive, but rather highlight what are the challenges to fully implementing SARA and achieving its intended primary purpose “to prevent wildlife species from being extirpated or becoming extinct” (SARA, Section 2).

Step 1—assessment—insufficient resources to meet legislative requirements

SARA identifies COSEWIC as the legal body for undertaking assessment of the conservation status of wildlife species in Canada (SARA Sections 14–22), where a wildlife species is defined as, “a species, subspecies, variety or geographically or genetically distinct population of animal, plant or other organism, other than a bacterium or virus, that is wild by nature and (a) is native to Canada or (b) has extended its range into Canada without human intervention and has been present in Canada for at least 50 years.” (SARA Section 2(1)). COSEWIC is comprised of 10 Species Specialist Committees representing 10 major taxonomic groups (including aquatic groups Freshwater Fishes, Marine Fishes, Marine Mammals, and Molluscs), an Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge Committee, and additional jurisdictional, non-governmental, and early-career members, and it is coordinated by the COSEWIC Secretariat of government employees (cosewic.ca). COSEWIC, more specifically each SSC, develops a list of candidate species, prioritizes the lists, and assesses high-priority species using guidelines outlined in a comprehensive, 409-page Operations and Procedures manual (

COSEWIC 2021). There is a legal requirement under SARA to review the classification of assessed species every 10 years (SARA, Section 24). Currently, wildlife species are re/assessed at a rate of about 50–60 species per year and, as of October 2023, 869 wildlife species, including 271 species from primarily aquatic taxonomic groups, have been assessed a conservation status of extinct, endangered, threatened, special concern, not at risk, or data deficient (

COSEWIC 2024).

COSEWIC is chronically underfunded. Between 2021 and 2024, its annual budget varied between $1.2 M and $1.9 M (

OAG 2024). Its funding has not increased concomitantly with the increasing number of wildlife species requiring assessment or reassessment, and, more than once, the committee told the government that it did not have the resources necessary to carry out its work (

OAG 2024). Based on the 869 species across the 10 taxonomic groups already assessed, on average, 87 reassessments need to be completed every year to meet the legal requirement of 10-year review of classification. Based on the current annual budget of $1.2–1.9 M to complete 60 assessments, the annual budget to complete 87 reassessments should be $1.45–2.75 M. This number does not include species on candidate and priority lists yet to be assessed for the first time and, as a result, many species of conservation concern remain unassessed (e.g., freshwater fishes—12 high-priority species, 12 mid-priority species; marine fishes—5; marine mammals—4; 3; molluscs—11;

COSEWIC 2024), and legislated requirements for reassessment are not met. A recent federal Office of the Auditor General (OAG) report found barriers to meeting targets included lack of resources, including budget (

OAG 2024). The

OAG (2024) report indicated that to reduce the backlog, 106 reassessments would be required per year, to assess all species on the COSEWIC priority list would require 152 assessments per year, and to assess all potentially at-risk species on the general status of species report (

CESCC 2022) would require 630 assessments per year, until 2030. Based on the current annual budget, these assessments would require an additional annual budget of $2.1–3.4 M to $12.6–20.0 M, respectively. Furthermore, many potential SAR lack sufficient data to inform assessment and typically remain low priority until data become available. However, there is no formal mechanism for funding data collection on such data-deficient species.

Taylor et al. (2023) identified the need for more funding for basic research, such as trends in the distribution and abundance of populations, to make sure status assessments were as accurate as possible. Another recent OAG report recommended that DFO funding be provided for data-deficient aquatic species, which DFO agreed to do (

OAG 2022). It is not clear how DFO will fund such data collection, either through new funding or re-allocated funding from other existing programs. While this partially addresses the problem, most data-deficient species have not yet been assessed by COSEWIC as they are considered lower priority. In fact, this response is counter productive as it requires that a species goes through the costly assessment process to be formally assessed as data deficient before funds are available to collect additional data that then may lead to a second assessment.

Recommendations

1.

Increase funding to COSEWIC to increase the number of species that can be re/assessed annually to decrease the backlog of new assessments of high-priority species and 10-year review of classification of assessed species and facilitate an increased rate of assessment for candidate species.

2.

Decrease requirements for the legally required 10-year review of classification. Initially, COSEWIC used update status reports for reassessments but, given the backlog, has been working on streamlining the requirements by replacing Status Assessment reports with shorter formats including status appraisal summary (SAS), rapid review of classification, addendum, and most recently, review of classification.

3.

Provide new, not re-allocated, funding to collect data for species identified as data deficient at the prioritization stage, not after COSEWIC assessment.

4.

More proactive collection of data for re/assessments by competent ministries, DFO in the case of aquatic species, as they know when species will be re/assessed several years in advance.

5.

Increase funding for developing and implementing more effective, science-based methods for monitoring the distribution and abundance of, and threats to, candidate species requiring assessment and listed species requiring reassessment.

Step 2—listing decisions—lack of transparency

COSEWIC assessments are forwarded as recommendations for listing under SARA to the Governor in Council (GIC), which acts by, and with, the advice of Privy Council (

https://www.constitutionalstudies.ca/2019/07/governor-in-council/). The GoC has 270 days to decide whether to list species under SARA—if no decision is made, then the species should be listed by default. Listing species automatically or by default after 270 days would be consistent with the precautionary principle, i.e., to action to prevent harm in the face of scientific uncertainty, adopted by the Government of Canada (

GoC 2003); however, it is well known that the majority of listing decisions take much longer than 270 days and none have been listed by default (

Ferreira et al. 2019) with the GoC employing a loophole of the 270 days starting when the COSEWIC recommendations are received by the GIC, not when species are assessed (

Mooers et al. 2007). Since 2004, 34 of 126 freshwater, and 85 of 104 marine, species assessed as at risk by COSEWIC were not listed with some listing decision over 10 years late (

OAG 2022). For example, Redside Dace (

Clinostomus elongatus) was not listed until 10 years after (13 April 2017) its 2007 assessment and, during that time, an additional two populations were lost (

Jackson and Mandrak 2025). Listing decisions are based on a Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS), which is used for most government decisions in general.

For SAR listing decisions, a RIAS typically includes science advice, socio-economic considerations, and public consultation (

Montgomery et al. 2021). For aquatic SAR, the science advice is usually provided in the form of a DFO-led, peer-reviewed recovery potential assessment (RPA) (

Montgomery et al. 2021; e.g.,

DFO 2023). The RPAs must be developed before the RIAS and subsequent listing decision, theoretically within 270 days after assessment. This is not a realistic timeline for the development of science advice if it is not initiated prior to the assessment date—this date can be estimated several years in advance of the actual assessment through the COSEWIC planning process.

Montgomery et al. (2021) found that, for freshwater fish SAR, the science advice was peer reviewed, transparent, and publicly available through the DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) website (

www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs), and the RIAS was available on the Canada Gazette (

www.gazette.gc.ca), but the socio-economic factors and detailed public comments considered in the listing decision were not publicly available. The latter is important as

Montgomery et al. (2021) concluded that listing decisions for freshwater fish SAR were not driven by science, and it was not clear what was the crux of the decision. Many marine SAR have not been listed due to socio-economic considerations (e.g., impacts on commercial fishing;

Mooers et al. 2007), typically not fully justified in a transparent manner but rather vaguely addressed in the RIAS or Order, which are not peer reviewed by independent authorities. Sometimes, species are sent back to COSEWIC because the assessment is deemed inadequate (e.g., lack of Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge in the report for Shortjaw Cisco (

Coregonus zenithicus) assessed as Threatened), but it is important to note that COSEWIC is legally required to assess species based on best available information and if that information is deemed insufficient, the species is either not prioritized for assessment or is assessed as data deficient.

Recommendations

1.

Develop a transparent, explicit high standard for not listing COSEWIC-assessed species (i.e., there must be compelling, objective reasons not to list a species).

2.

Peer review by independent authorities all elements of listing decisions and publicly provide them in detail, similar to the availability of the science advice on the DFO CSAS website, as also recommended by

Taylor et al. (2023).

3.

Determine a realistic deadline for a listing decision. At current levels of federal funding, 270 days is not sufficient for compiling the information required to make a listing decision (

Mooers et al. 2007). Recently, the GoC has targeted making listing decisions within 3 years of receipt of COSEWIC recommendations by GIC (

OAG 2023) and DFO committed to reducing listing delays (

OAG 2022). This was also recommended by

Taylor et al. (2023). Use the precautionary principle to list species by default if deadlines are not met.

4.

More proactive preparation of scientific advice and socio-economic analyses by competent ministries, DFO in the case of aquatic species, to inform listing decisions as they know when species will be re/assessed several years in advance.

5.

Increase funding to facilitate the provision of more effective and timely science advice and the required legal components (e.g., RIAS) of the listing decisions within the SARA-mandated time lines.

Step 3—recovery planning—not prescriptive enough

If a species is listed under SARA, then a recovery strategy must be completed within 1 year for endangered species and 2 years for extirpated and threatened species, and a management plan within 2 years for special concern species (SARA Sections 42(1), 68(1)). Recovery strategies outline recovery measures that should be implemented to reach recovery goals of preventing the extinction of species; whereas, management plans outline goals and objectives for maintaining sustainable population levels before species are in danger of becoming extinct. If a species is assessed by COSEWIC as at risk of extinction, but not listed under SARA, it will not receive the benefit of this and subsequent steps. Until recently, few (21%) of the timelines were met and were often years late (fishes median = 5 years; molluscs 4 years), some as late as 13 years (

Ferreira et al. 2019) and butting up against reassessments that could change document requirements (e.g., species assessed as special concern required a management plan and, if reassessed as threatened or endangered, would then require a recovery strategy). For example, a recovery strategy for Redside Dace was not released until 2024, 13 years after it was first assessed as endangered, 7 years after it was listed, and 6 years after its legal deadline during which time three populations were lost (

Jackson and Mandrak 2025).

Recovery action plans must be completed for those species with recovery strategies (SARA Section 47), but have no legal deadlines nor legal requirement to be implemented and are dependent upon the completion of recovery strategies. To date, there have been very low rates of, and delays in, completion. Recovery strategies and management plans provide and prioritize generic high-level actions, such as science, monitoring, outreach, and enforcement, that should be undertaken to protect and recover the species. Recovery action plans outline activities required to meet the recovery goals and objectives identified in recovery strategies and cannot be initiated until such strategies are completed and, hence, are substantially delayed as well. For aquatic SAR, much of the scientific advice for recovery planning is in the form of an RPA, which includes evaluating the COSEWIC assessment, determining whether recovery is feasible, setting distribution and recovery targets, and identifying critical habitat and allowable harm, i.e., human-induced harm that will not jeopardize the survival or recovery of an aquatic species (

DFO 2022) (e.g.,

DFO 2023).

Because the GoC largely depends on non-GoC organizations and individuals to implement recovery actions, those actions found in recovery documents are typically not sufficiently prescriptive to be followed by non-experts. SARA allows for the development of ecosystem, multispecies, and species-specific recovery documents (SARA Sections 41(3), 67). As many watersheds in southwestern Ontario have multiple aquatic SAR (

Anas and Mandrak 2022;

Rumball 2023), some of the earliest recovery strategies were ecosystem based (e.g.,

Dextrase et al. 2003;

ARRT 2005), and the goal was to cover most of southwestern Ontario using watershed-based ecosystem recovery strategies. However, in the late 2000s, the government stopped funding the development of ecosystem-based recovery strategies in favour of species-specific recovery strategies that, although less ecological sound and cost effective, more easily allowed reporting on progress on the recovery of individual species. Recently, the government has once again supported the development of “bundling” ecosystem and multispecies recovery documents (e.g.,

DFO 2020), more likely for cost-saving as much as ecological reasons.

Recovery documents were initially authored by recovery teams comprised of species experts who met regularly in person in facilitated workshops to develop recovery actions. More recently, the GoC has assumed authorship of the recovery documents and depended less on input from recovery teams and, hence, species experts. Based on my experience with freshwater fishes in Ontario, species-specific recovery teams were combined into a single team that no longer met in person, and experts were asked to review, with no notice and short deadlines, recovery documents written by GoC employees who may be experts in recovery document writing, but typically not on the species.

Recommendations

1.

Meet legislated timelines for the development of recovery documents.

2.

Legally mandate that recovery action plans be completed in a timely (1–2 years) manner and be implemented.

3.

Actions outlined in recovery documents should be sufficiently prescriptive to be implementable by non-experts.

4.

Actively engage recovery teams to assist in the development, regular review, and, as necessary, revision of recovery documents.

5.

Support the development of ecosystem recovery documents as an ecologically sound approach also recommended by

Taylor et al. (2023).

6.

More proactive preparation for recovery document development by competent ministries, DFO in the case of aquatic species, as they know when species will be re/assessed several years in advance.

7.

Increase funding to facilitate the provision of effective and timely science advice and the completion of recovery planning within the SARA-mandated time lines.

8.

Increase funding for developing more effective and timely science-based methods to guide implementation of recovery actions.

Step 4—implementation of recovery plans—a tragedy of the commons?

SARA indicates that, “all Canadians have a role to play in the conservation of wildlife in this country, including the prevention of wildlife species from becoming extirpated or extinct, there will be circumstances under which the cost of conserving species at risk should be shared, and the conservation efforts of individual Canadians and communities should be encouraged and supported” (SARA Preamble). The GoC undertakes very limited recovery actions itself, but rather delegates recovery primarily through agreements with provinces and territories and through funding programs such as the Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk, Canada Nature Fund for Species at Risk, and the Habitat Stewardship Program (

www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/sara-lep/index-eng.html). However, recovery documents provide insufficient guidance on how to implement recovery actions, and there is insufficient coordination to ensure that there are no species or geographic gaps in the implementation of actions. These gaps, particularly on public lands such as waterways, lead to our own tragedy of the commons (

Hardin 1968), wherein self-interest is replaced with neglect as no one assumes responsibility to implement recovery actions.

Rumball (2023) examined 98 projects funded in Ontario by the federal Habitat Stewardship program for aquatic SAR between 2006 and 2017. They found that, in southwestern Ontario, an area with greatest richness of aquatic SAR in Canada (

Anas and Mandrak 2022), several aquatic SAR and several watersheds with multiple aquatic SAR were not targeted by any projects at all. These gaps may be identified in the required GoC 5-year interim progress reports on individual species, but this would not guarantee that already delayed actions would be undertaken in the future. The results of the

Rumball (2023) study exemplify the potential shortcomings of the GoC delegating, without coordinated and prescriptive guidance, the implementation of recovery plans to other levels of government and to Canadians.

Recommendations

1.

Provide legislative timelines and more prescriptive guidance for recovery action plans, and GoC should fund recovery implementation experts (e.g., restoration ecologists) to help Canadians implement meaningful recovery actions.

2.

Develop living databases to catalogue recovery actions and associated effectiveness monitoring to identify and address species and geographic gaps (

Rumball 2023) and to determine what recovery actions are effective.

3.

Increase funding to facilitate more taxonomically and geographically comprehensive implementation of recovery actions.

4.

Increase funding for developing more effective and timely science-based methods to evaluate effectiveness of recovery actions.

Step 5—reassessment and monitoring—realistic timelines and adequate effort?

SARA requires that the conservation status of listed species be reassessed every 10 years, and DFO provides 5-year interim reports for listed species outlining the current status of the species and its recovery strategy and action plan, and what recovery actions, if any, have been implemented. The basis for both 5-year reports and 10-year reassessments should be monitoring of the population status of, and threats to, the species. Such monitoring is essential to reassessments of conservation status and evaluating whether implemented recovery actions have been effective. It would be naïve to expect the recovery of any species, within 10 years of listing (e.g., by comparing status between subsequent assessments;

Favaro et al. 2014), a fraction of generation time for some, and less than three generations for many, SAR. Therefore, it is critical that populations be monitored using targeted, standardized methods over the long term (i.e., decades), similar to the stock assessments used for commercial species. To date, most changes in status at reassessment are the result of changes in data availability or assessment methodology, not population status (

Moore et al. 2017;

ECCC 2025).

Meaningful reassessments are not possible without up-to-date standardized data on population status and threats, notwithstanding COSEWIC’s lack of resources to complete timely 10-year reassessments noted above. The delay in reassessments is tautological—reassessments of species for which there are no new data are unlikely to result in a status change and, therefore, are prioritized lower by COSEWIC, further delaying the timeline. Monitoring plans should be developed using current scientific principles, such as detection probability (e.g.,

Lamothe et al. 2023;

Bennett et al. 2024), and should be adaptive and modified as new methods (e.g., eDNA;

Sandhu et al. submitted) become available. To date, no monitoring plans for listed aquatic SAR have been posted to the SARA registry (

GoC 2024d), and few are available for other taxa (

Buxton et al. 2022) Once monitoring plans are effectively implemented in the long term, what constitutes “recovery” will need to be determined. Currently, the recovery is defined as “a return to a state in which the risk of extinction or extirpation is within the normal range of variability for the species” (

GoC 2024c). Based on this definition, recovery will be very difficult to determine as monitoring is not typically implemented for a species during its normal range of variability of risk of extinction prior to an increased risk of extinction leading to its at-risk assessment.

Recommendations

1.

Develop monitoring plans for every at-risk species (consider species guild or ecosystem approaches) prior to the 5-year interim reporting milestone.

2.

More proactively preparation for reassessments by competent ministries, DFO in the case of aquatic species, as they know when species will be reassessed several years in advance.

3.

Increase funding to facilitate monitoring of distribution, abundance, and threats required for reassessment.

4.

Increase funding for developing more effective science-based methods for monitoring of distribution, abundance, and threats required for reassessment.

Indigenous knowledge—recognized but not meaningfully included

Indigenous knowledge is prominently recognized (as “Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge”) in SARA (e.g., Sections 2, 3, 8, 10, 16, 18, 39, 66, 83, 103), yet requirements for incorporation of Indigenous knowledge at all steps in the SARA process have not been adhered to (

Olive 2012;

Hill et al. 2019;

Turcotte et al. 2021). Indigenous knowledge system has been characterized as a “cumulative body of knowledge, practices, and beliefs, evolving, and governed by adaptive processes and handed down and across (through) generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with one another and with their environment” (

Diaz et al. 2015). Indigenous knowledge has been included in relatively few COSEWIC assessments of aquatic species (the Lake Sturgeon

Acipenser fulvescens report is one of the few aquatic examples;

COSEWIC 2017).

Oloriz and Parlee (2020) identified the availability of extensive Indigenous knowledge on White Sturgeon (

Acipenser transmontanus), and the failure to incorporate this knowledge into the 2012 COSEWIC assessment of this species as a missed opportunity. The paper concluded that “a biocultural diversity conservation approach that reflects both ecological and socio-cultural values, and is informed by scientific and Indigenous knowledge systems, is a more sustainable approach to the management of the white sturgeon and other species at risk”. Such a biocultural approach to conservation assessments has been recently developed for the Northwest Territories (

Singer et al. 2023). Lack of Indigenous knowledge in recovery strategies has also been identified, with only 48% of 257 recovery strategies examined providing evidence of inclusion of Indigenous knowledge bases on document context analysis (

Hill et al. 2019). The mean score (0 (no involvement) to 5 (highest level of collaboration)) of incorporation of Indigenous knowledge for those recovery strategies ranged from 0 (mosses) to 2 (fishes) across 10 taxonomic groups. Of the recovery strategies for aquatic species examined, Indigenous knowledge was detected in 32 of 44 fish strategies (mean score = 2), and 7 of 14 mollusc strategies (mean score = 1.5), and the mean score for strategies under the jurisdiction of DFO (i.e., aquatic species) was highest of the three responsible agencies, but it is important to note these scores are low (

Hill et al. 2019). To my knowledge, there has been no systematic review of the use of Indigenous knowledge in recovery implementation. There is an Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk that supports the development of Indigenous capacity to participate in the implementation of SARA (

GoC 2024a) for both aquatic and terrestrial species, but lists of funded projects are not publicly available. The recently developed federal policy Indigenous-Led Area-Based Conservation and associated funding (

GoC 2024b), although more broadly targeting biodiversity through protected areas, is a positive step towards better incorporating Indigenous knowledge into recovery implementation.

Recommendations

1.

Meaningfully use a knowledge-sharing approach (

Wong et al. 2020) in every step of the SARA process to fully include Indigenous knowledge in every step of the SARA process as recognized in the Act.

2.

Increase funding to facilitate the incorporation of Indigenous knowledge into the SARA process.

Conclusions—elephants in the room

At 20 years since implementation, SARA has its challenges, both foreseen and unforeseen. The unforeseen, although certainly not unknown at the time, include the emerging large-scale threat of climate change to SAR, a threat that is difficult to incorporate into assessments and address in recovery actions. Also largely unforeseen is the extent to which science would be required to guide each step of the SARA process. The foreseen, but obviously underestimated, includes the amount of funding required to implement the SARA process and, particularly, to support the science underpinning it. Detailed budgets should be made publicly available for transparency and to allow more accurate estimates of the budget required to fulfill legal mandates.

The role of climate change in assessing and recovering SAR has been poorly incorporated into the SARA framework. Climate change may impact aquatic species, including SAR, by modifying of environmental regimes, including changes in streamflow, water temperature, salinity, storm surges, and habitat connectivity, resulting in physiological changes, disrupted spawning cues, extinctions and invasions, and altered community structure (

Paukert et al. 2021). Climate change was rarely identified in COSEWIC assessments prior to 2012, when COSEWIC adopted a threats calculator that required assessing the impact of climate change. Despite this requirement,

Woo-Durand et al. (2020) found climate change to be the least important threat to the 814 SAR across taxonomic groups included in their study; however, when including species for which climate change was listed as a probable or future threat, climate change rose to the fourth most important threat. Climate change was identified as a threat for 44.1%, and not identified at all for 43.5%, of listed species (

Naujokaitis‐Lewis et al. 2021).

McKelvey and Mandrak (2023) found that climate change was the primary threat for 35% of 65 freshwater fish SAR. Climate change may be less likely to be identified as a threat due to uncertainties associated with understanding its impacts (

McCune et al. 2013). Furthermore, climate change is likely to interact with other threats, increasing the severity of those threats (

Naujokaitis‐Lewis et al. 2021). Recovery actions related to climate change were present in recovery strategies for 46.0% of listed species, but only specific to population and habitat actions in 3.6% of recovery strategies (

Naujokaitis‐Lewis et al. 2021).

DFO and ECCC are the federal, Western science-based departments, and science is essential to the effective implementation of science-based legislation such as SARA. I have focused on the legislative requirements of the SARA process; however, science is the foundation of every step in the process. Assessment and reassessment require science to identify the most effective methods for monitoring the distribution and abundance of, and identifying the threats to, species. Recovery planning is largely based on the scientific advice provided at the listing-decision step (e.g., RPA for aquatic species) and identifying and evaluating effective actions at the recovery implementation step. However, there are many knowledge gaps in the science supporting the SARA process (e.g., freshwater fishes,

Drake et al. 2021).

My recommendations would require large increases in funding, as the current funding is woefully inadequate to undertake current legislated requirements of SARA, let alone the aspirational goals of actually recovering species to the point that they can be down listed (i.e., the intent of SARA). The extent of this budget inadequacy is difficult to determine as detailed federal conservation budgets are not publicly available and, as a result, analyses to determine the funding required to fully implement SARA cannot be undertaken. The 2024/25 budget for ECCC was $2 760 969 226 (

ECCC 2024). Funding for all aspects of the SAR program is within the core responsibility of Conserving Nature, which had a budget of $736 720 545 shared among six key activities. No further breakdown of funding is provided in

EEEC (2024) and, assuming equal funding among the six activities, the Species at Risk activity funding would be $123 M. The 2024/2025 budget for DFO, responsible for aquatic SAR, was $4 685 180 404 (

DFO 2024). Funding for all aspects of the aquatic SAR program is within the core responsibility of Aquatic Ecosystems, which had a budget of $458 054 031 shared among five key activities. No further breakdown of funding is provided in

DFO (2024) and, assuming equal funding among the five activities, the Conservation and Recovery of Species activity funding would be $91 M. Therefore, the total annual budget for SAR is estimated to be $214 M. In the United States, the mean annual funding per ESA-listed species in 2020 was US$814 014, which was identified as insufficient (

Eberhard et al. 2022). Based on the 660 species listed under SARA as of May 2023 (

GoC 2023), the equivalent funding in Canada would be US$537 249 240, of which, proportionally (162 of 660 species;

GoC 2024e), US$134 312 310 should be for aquatic SAR. If we can find billions of dollars to fight an unexpected pandemic, surely, we can find a fraction of such funding to protect an important component of Canada’s natural heritage. For example, the GoC has not listed any of the Pacific salmons (

Oncorhynchus spp.) assessed as at risk of extinction by COSEWIC, yet has committed $646 M to their recovery (

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/fed-plan-to-save-pacific-salmon-1.6057761) without explaining why this is not being done within the SARA framework (

https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/campaign-campagne/pss-ssp/index-eng.html). Such actions undermine the credibility of the SARA process and indicate that substantial additional funding can be made available.

SARA is still in its infancy—it is unrealistic to expect that, even if there were unlimited resources, species would recover in the 20 years since the implementation of SARA. The imperilment of many SAR is the result of decades of cumulative impacts of human modifications to the landscape (e.g., deforestation, wetland draining, dams, pollution)—the meaningful recovery of these species will require meaningful recovery actions at the ecosystem scale sustained over long time frames. Despite its implementation growing pains, woefully inadequate funding, and the challenge of the Minister’s listing discretion, I believe that the Act we have is better than no Act at all, and many species have benefitted from it. With strong leadership and increased funding, the Act could move from struggling to minimally meet its legislative requirements to achieving its aspirational purposes of preventing wildlife species from being extirpated or becoming extinct and providing for their recovery.