Using the Framework Method to support collaborative and cross-cultural qualitative data analysis

Abstract

With Inuit organizations leading the way, there is a growing opportunity for meaningful partnerships between Inuit and visiting researchers to create impactful research programs and policy initiatives that reflect Inuit priorities. Collaborative research methods, where Inuit and visiting researchers work together to meet community needs, offer a potential avenue for braiding knowledge systems, and therefore have become an increasingly popular way to conduct research in the Arctic. In this paper, we outline our use of the data analysis method known as the “Framework Method” during the Imappivut Knowledge Study, a participatory mapping project led by the Nunatsiavut Government. We reflect on both the method's applicability and its usefulness for future research conducted in collaboration between Inuit and non-Inuit researchers. We find that the Framework Method allowed us to work in an iterative and adaptive manner, resulting in comprehensive findings for marine spatial planning. The method also supported data sovereignty for the Nunatsiavut Government. The Framework Method can be used to allow Nunatsiavut greater control over the data internally and self-determining access to external researchers.

Introduction

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (2018) or the National Inuit Strategy on Research explains that research is an essential aspect of self-determination and political advancement for Inuit. Where Inuit have the power to identify research questions, they can advance their own priorities for Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit homelands. With the power to determine who can conduct research, and how, Inuit can set the agenda and prevent harmful research practices. This is about more than a normative power over research. Indigenous knowledge systems encompass entire paradigms that are connected to the land, the people, and their mutual history (Latulippe and Klenk 2020; Pedersen et al. 2020). Inuit-led research advances Inuit governance by strengthening those connections, and centering the worldviews, values, and well-being of the people.

To advance Inuit self-determination, many Inuit communities and land claim organizations have launched initiatives and research programs that inform community development, support territorial autonomy, and celebrate and preserve their cultures (Tester and Irniq 2008; Ferrazzi et al. 2018). In addition, Inuit land claim organizations, governments, and other bodies have developed protocols and policies to guide research that supports Inuit self-determination in research (e.g., Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami 2018) and ethical research conduct (e.g., Inuit Circumpolar Council 2021).

As Inuit have asserted their rights in their homelands, non-Inuit researchers, particularly those from southern institutions, are at last recognizing that their approaches alone are insufficient for understanding and governing marine and coastal environments. Inuit have rich knowledge systems that draw on thousands of years of learning on the land, and yet their knowledge has largely been disregarded in science and policy (McGregor et al. 2010). Instead, there is a long history of exploitative and unethical research practices in Inuit Nunangat, perpetrated by visiting researchers that have damaged communities while bringing benefits and accolades to non-Inuit researchers (Brunger and Wall 2016; Hayward et al. 2020; Held 2020). For research to appropriately respect land claims and other established Indigenous rights, scientists need to adopt collaborative and empowering methods that uphold Indigenous epistemologies and ontologies to generate knowledge that can be used to drive policies that support Indigenous values and priorities for management.

With Inuit organizations leading the way, there is a growing opportunity for meaningful partnerships between Inuit and visiting researchers to create impactful research programs and policy initiatives that reflect Inuit priorities. The National Inuit Strategy on Research identifies priority areas for research that supports Inuit self-determination, including advancing Inuit governance through research, enhancing ethical conduct, funding projects that support Inuit priorities, maintaining Inuit control over data, and building capacity in Inuit Nunangat into the future (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami 2018). It has also been well documented for the scientific community that doing research in partnership produces outcomes that benefit conservation needs, legal imperatives, and human well-being (Castleden et al. 2012; Cunsolo Willox et al. 2012; Henri et al. 2020; Sawatzky et al. 2020). It is therefore crucial that non-Inuit researchers entering the north—when there is a need for them at all—develop partnerships with Inuit to guide every facet of their research.

One of the biggest challenges of partner-driven research is working across and between different knowledge paradigms: Western science on the one hand, which we define as “proudly objective, quantitative, short-term, reductionist and materialist knowledge that privileges its intellectual schema for strictly empirical knowledge” (Kimmerer 2018, p. 51) and Inuit Knowledge on the other, which we define (briefly) as a place-based, multigenerational, and experiential knowledge system (Pedersen et al. 2020; Liboiron 2021a). There is a growing need for frameworks and methods that help support bringing these two systems together to redress colonial harms and support Inuit well-being (Pedersen et al. 2020; Petriello et al. 2022; Zurba et al. 2022). This paper provides reflections from one such partnership between non-Inuit and Inuit researchers in Nunatsiavut, one of the four subregions within Inuit Nunangat. We share our experiences with a data analysis method called the Framework Method to consider its use in cross-cultural collaborative research. We ask: to what extent was the Framework Method an effective tool for bringing together Western and Labrador Inuit Knowledge? And did the process or outcomes result in any contributions to Nunatsiavut governance?

We begin by positioning ourselves in relation to our research, and by setting out our shared understanding of the properties of knowledge systems, before turning to the work we conducted. The research project in question was the Imappivut Knowledge Study that was led by the Nunatsiavut Government, the land claim government for Inuit of Labrador. The study gathered Labrador Inuit Knowledge, values, and priorities about the marine environment to ensure Inuit perspectives guided marine planning throughout Nunatsiavut. Recorded participant mapping interviews were integrated into a Geographic Information System platform following a methodology established by the consulting company the Firelight Group.1 The Nunatsiavut Government recognized that the analysis and reporting of these data presented an opportunity to partner with academic researchers at Dalhousie University to provide training and enhance research capacity within Nunatsiavut and produce an analysis of interview data that could support future Inuit-led scientific marine research and conservation planning. The Nunatsiavut Government formed a research partnership composed of settler and Inuit researchers living in Nunatsiavut, and researchers based in southern Canadian communities to codevelop a method of analysis.

The result of this endeavour is a collaborative and capacity-sharing research process. In this paper, we reflect on that process to demonstrate how it led to a shared understanding of Labrador Inuit values and priorities in the marine environment and supported Nunatsiavut's sovereignty over their data and marine planning process.

While the project is multifaceted and ongoing, we choose to focus on the data analysis method we undertook in the summer and fall of 2019. We outline the method we codeveloped for this analysis and reflect on both its applicability to the Imappivut data and its usefulness for future research. By narrowing in on this one step in the research process, we hope to provide some practical tools for research collaboration between Inuit and Western researchers.

Positionality

The Imappivut Knowledge Study is owned and designed by the Nunatsiavut Government. The analysis team (the authors on this paper) consists of Labrador Inuit and settlers. Some team members are academic researchers working in institutions in southern Canada, and others are researchers employed by the Nunatsiavut Government. In both groups, there are both Inuit and settler team members. In this paper, the researchers coming from Dalhousie University who contributed to the project are referred to collectively as “visiting researchers” to distinguish them from the researchers employed by the Nunatsiavut Government. During the analysis, all the visiting researchers travelled to Nain to discuss the method design. The analysis itself was conducted by one visiting researcher, Cadman (settler), and two government researchers from the Nunatsiavut Government, Denniston and Dicker (Labrador Inuit). This paper was first drafted by Cadman, following years of conversations with the rest of the research team, and Denniston in particular. Cadman, Dicker, and Denniston contributed writing to the paper. All team members commented on and edited the submission.

Collaborative research and braiding knowledges

Indigenous Knowledges are more than a collection of data points that can be easily inserted into a Western scientific method (Latulippe and Klenk 2020). Indigenous Knowledges are entire knowledge systems inclusive of all cultural and spatial contexts: the cosmologies, ontologies, epistemologies, axiologies, and methodologies that make up the ways people understand and interact with the world (Wilson 2008). Deborah McGregor describes Indigenous Knowledge as inclusive of all laws, morals, and ethics that guide proper conduct (McGregor et al. 2010). Indigenous knowledge systems have “governance value”, meaning that Indigenous Peoples carry their own social, legal, and economic institutions that guide the way their communities and societies operate (Whyte 2018).

In an Inuit context, Tester and Irniq (2008) describe one form of Inuit Knowledge, Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ), as encompassing “all aspects of traditional Inuit culture including values, world-view, language, social organization, knowledge, life skills, perceptions, and expectations” (p. 48). They further describe IQ as a “seamless” body of knowledge, meaning that there are no discernible boundaries between spiritual and factual components of the system, where “everything is related to everything else in such a way that—counter to the logic of Western science—nothing can stand alone, even in the interest of gaining an appreciation of the whole” (p. 49). Importantly, the place-based nature of Indigenous Knowledges means that each knowledge system is unique to the land and the language from which it arises (Williams 2018), so research must be grounded in a specific place and with specific people to have meaning. We note therefore that while Labrador Inuit Knowledge is related to IQ, it is a distinct system that is bound up with Labrador Inuit lands, histories, and dialects.

How, and whether, Indigenous knowledge systems can be “braided” with a Western knowledge system is still much debated by both Indigenous and Western scholars, but the concept speaks to the idea of increased strength when knowledge systems are brought together (Youngblood Henderson 2019; Pedersen et al. 2020) There are many research projects that have added value and grown capacity through partnership-driven work between Western scientists and Indigenous experts (e.g., Ljubicic et al. 2018; Carter et al. 2019; Henri et al. 2020; Beveridge et al. 2021, to name a few from the Arctic region). Essential to knowledge-braiding practice is the recognition that Indigenous Knowledge holds at least the same weight and value as Western science—that Indigenous Knowledge holders are scientists in their own right (Liboiron 2021b; Reid et al. 2022). This allows for research that is enriched by privileging all experts both as researchers and as informants.

To fulfill this goal of braiding disparate knowledge systems into research, we must consider ways of working together that do not allow one knowledge system to subsume another but enable knowledge systems to speak together. Collaborative research methods, where Inuit and visiting researchers work together to meet community needs, offer a potential avenue for braiding knowledge systems and therefore have become an increasingly popular way to conduct research in the Arctic (e.g., Breton-Honeyman et al. 2016; Carter et al. 2019; Henri et al. 2020).

Collaborative partnerships require creative and iterative methods that allow multiple cultures and knowledge systems to dictate the entire life cycle of a research project, inclusive of both the process and the outcomes. Collaboration does not guarantee that power will be equitably shared among partners, and so considerations must be made of the project governance, adherence to ethical guidelines, methodological approach, and research outcomes (Latulippe 2015; Latulippe and Klenk 2020; Norström et al. 2020).

Even the reflections in this paper are bound up in this braiding process, because reflection allows us the opportunity to evaluate our progress, in order that we may keep improving the method into the future. This accountability—to the project, the communities, and to each other—is required to carry out methods that respect and value multiple ways of knowing (Liboiron 2021b).

Some Indigenous scholars caution that collaboration often still relies on Western scientific methods and subsumes Indigenous Knowledges as secondary (Wilson 2008; Watts 2013; Todd 2016). Careful reflection of the power dynamics between research partners is required in the research design to create methods that respect and value multiple ways of knowing (Liboiron 2021a). Focusing on process also means that partners are less concerned about the outcomes of integrating two scientific orders, and can concentrate on mutual learning and empowerment as outcomes in their own right (Chambers et al. 2022; Petriello et al. 2022).

Imappivut

The Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement (LILCA) was signed in 2005, creating the Labrador Inuit Settlement Area (LISA) and Nunatsiavut, meaning “Our Beautiful Land”. The LISA covers 72 520 km2 of land and 48 690 km2 of adjacent tidal waters (referred to as the Zone). There are over 2550 beneficiaries of the land claim agreement living in Nunatsiavut, in the communities Nain, Hopedale, Makkovik, Postville, and Rigolet. Many more beneficiaries live just outside the region, in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Labrador, and more widely across Canada.

Imappivut (“Our Oceans”) is an initiative of the Nunatsiavut Government to develop a marine plan for Nunatsiavut and the surrounding area.2 As part of Imappivut, the Nunatsiavut Government Department of Lands and Natural Resources conducted a knowledge study that consisted of participatory mapping and qualitative interviews. The project is designed to support the implementation of Chapters 6 and 9 of the LILCA, which concern ocean management and conservation. Imappivut is rooted in Labrador Inuit Knowledge and community priorities for the marine environment.

The Imappivut Marine Planning Initiative was designed by the Nunatsiavut Government in consultation with Nunatsiavut beneficiaries. In summer and fall 2017, project leaders from the Nunatsiavut Government travelled within Nunatsiavut communities and spoke with community members about their intention to conduct the project and elicited information about community priorities and research questions. Feedback from community members indicated that members felt it would be essential for the project to collect Inuit Knowledge and values in the marine environment. Based on these conversations, the project leaders designed the Imappivut Knowledge Study to help identify community priorities and Inuit Knowledge that would help scope and direct the project into the future, embedding Labrador Inuit perspectives into marine planning and decision-making. This project was reviewed and approved by the Nunatsiavut Government Research Advisory Committee before data collection began, and all participants gave informed consent to the research.

For the Knowledge Study, government researchers collected stories from Labrador Inuit on how they use and value the marine environment and mapped out areas of significance for livelihoods, domestic harvesting, recreation, and cultural value. Data collection for the project was conducted by team members in the five communities within Nunatsiavut and Happy Valley-Goose Bay and Northwest River (“Upper Lake Melville”), which are communities outside of the region but are home to many beneficiaries of the LILCA. Researchers travelled in groups of two or more to each community to speak with participants in 2018–2019.

Two types of data were collected simultaneously: unstructured interview data and spatial mapping data. Researchers would project a large Google Earth map on the wall, and then ask participants how they use or value the marine environment. The participants would then use a laser pointer to show significant places on the map, such as hunting grounds, cabins, and travel routes. One researcher would focus on interviewing the participants by asking clarifying questions or prompting the participants to share more. For example, if a participant did not know where to start, the interviewer would frequently suggest that they start with the site of their cabin or a seasonal place they frequented. While the participants spoke, the interviewer took notes to ensure accuracy and to record information that would not be captured in the map or audio recordings, for example, that a particular goose hunting location was where the participant shot their first goose, or that the site of a cabin has been passed down for multiple generations. Meanwhile, the second researcher would focus on the map, and trace the areas shown by the participants using points, lines, and polygons to indicate spaces of use. Each spot on the map is labelled with a code that explains the feature of interest—such as the species being hunted or a significant environmental feature. The researchers would speak the code out loud as it was recorded on the map so that the information is recorded both as a spatial point and as interview data. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed and Google Earth maps were processed using ArcGIS software.

To date, government researchers have conducted 48 interviews with 54 participants. This discrepancy is because some interviewees chose to be interviewed together, including siblings, parent and offspring, and married couples. Interviews are a maximum of 2 h long and typically last approximately 90 min. Participants have mapped 2295 points along the Nunatsiavut coastline. Note that in some communities, key knowledge holders and hunters were unable to participate in the first round of community interviews for various reasons; therefore, it is expected that this number will grow as the project is ongoing and more interviews are planned in 2023.

In what is considered phase one of the project, data analysis of the Imappivut Knowledge Study interviews was conducted in 2019 by a team of researchers that included Labrador Inuit and visiting researchers from outside the region. The team was led by Nunatsiavut Government employees in the Department of Lands and Natural Resources. The majority of the analysis was carried out by two researchers: one visiting researcher from Halifax, Nova Scotia (Cadman, settler), and one government researcher from Nain, Nunatsiavut (Dicker, Inuk). The design of the process and the data analysis took place between August and November. During this time, the visiting researcher travelled to Nain, Nunatsiavut and lived in the Nunatsiavut Research Centre so that the researchers could work together in person, as well as speak in person with Nunatsiavut Government staff who conducted the actual interviews in the communities. This meant that the analysis was truly a collaborative effort that relied on multiple knowledges and skill sets to achieve a holistic understanding of the data. In designing this analysis, project partners identified three research objectives.

1.

To create an inventory of the data. The information collected from the unstructured interviews covers a broad range of topics, as well as rich details about people's lived experiences on the land, water, and ice of Nunatsiavut. It would be possible to use this dataset to explore a range of questions related to the marine environment and surrounding area in Nunatsiavut. This first analysis presented an opportunity to create an index for the data. An index allows future researchers or data managers to easily access all the information included in the interviews about topics of interest.

2.

To identify the values and needs of Nunatsiavut beneficiaries that will guide conservation and management in the marine environment. Beyond steering research priorities, the Imappivut Marine Plan will be an important tool for managers and policy makers to align their work with underlying values held by Labrador Inuit. The Imappivut Knowledge Study interviews reveal some of the deeply held beliefs and activities that make up Labrador Inuit culture. This will be useful for creating a record in time of the particular cultural values and interests of Labrador Inuit for longitudinal work that links historical, present, and future data. The results of this work can be used to create new policies that reflect the shared cultural values of Labrador Inuit.

3.

To highlight priorities for future research. The results of the Imappivut Knowledge Study are intended to direct environmental research in Nunatsiavut over the coming decade. This supports the guidelines set out by the National Inuit Strategy on Research that all research conducted in Inuit Nunangat should be grounded in priorities set by Inuit. The third objective for this analysis was therefore to identify what Labrador Inuit believe is important for the preservation of livelihoods, culture, and well-being in the waters adjacent to Nunatsiavut, and to record their observations and questions about change in the marine environment.

2

Method

The Imappivut Knowledge Study will have a direct effect on conservation and livelihood for Labrador Inuit in the decades to come and it was therefore especially important to ensure the analysis accurately and respectfully reflected the contributions from participants. Based on the goals of this project and the overall priorities of the Imappivut Marine Planning Initiative, we determined that a modified version of the Framework Method would be the best approach to suit the needs of the project. The Imappivut Knowledge Study was reviewed and approved by the Nunatsiavut Government Research Advisory Committee per Nunatsiavut's guidelines for ethical research. Participants in the research gave informed consent prior to participating in an interview. The Framework Method was originally developed for applied social research (Ritchie and Spencer 1994) and has been used particularly in the field of health research (Srivastava and Thomson 2009). It is recognized for its usefulness for collaborative research, as well as its ability to produce strategic, policy-oriented results (Read et al. 2004). The Framework Method was originally chosen for analysis because the coding structure mirrored the method used to label the spatial data points. During the mapping process, each geographic point, line, or polygon was labelled in the GIS system with an alphanumeric code that referred to the thing that was being identified—usually a species or a significant place. Our iteration of this method developed overtime as we found ways of capturing the nuances in the interview data.

The Framework Method contains five steps:

1.

Familiarization

2.

Developing a framework

3.

Indexing

4.

Charting

5.

Mapping and interpretation

Framework Method in practice

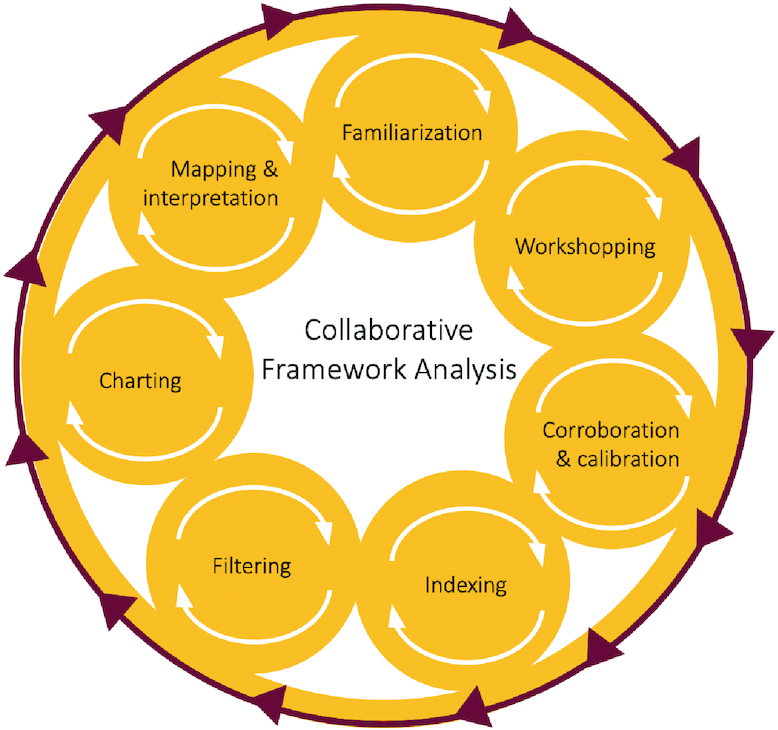

In practice, we found that many substeps and adjustments were required to make the method suitable for our needs, which included principles of collaboration and capacity sharing. To adapt this method to our collaborative context, we adjusted the analytic process as detailed below. Some of these adjustments were made before the analysis began; however, we found that flexibility was important during the analysis as well. We adjusted the analytic process listed above to be suitable for this collaborative research program, which is explained in detail in Fig. 1 below:

Fig. 1.

We conceptualize the analysis process as a cycle that begins after the data have been collected (Fig. 1). Each step of the analysis is represented by a yellow circle. The cycle is also iterative and requires that researchers continually communicate with one another for feedback and accountability. These activities are represented by the white arrows in Fig. 1, as team members revisit their assumptions and integrate new ideas from the team in every step.

Familiarization

This step involves researchers familiarizing themselves with data and creating a list of topics representing the key ideas in the data. These broad categories represent the types of information that will be important for the research problem.

In the Imappivut Knowledge Study analysis, visiting researcher Cadman reviewed transcripts of the interviews and developed an initial list of key concepts and themes in the data. Cadman presented this set of categories to the research team for feedback. The final list became the framework for analysis.

Workshopping

In usual use of the method, this step is known as “developing a framework”. In general, the researchers are expected to sort these key ideas or themes into categories. They are encouraged to keep an open mind and allow these categories to develop in an inductive way; it is recognized that the research problem will help shape the categories.

In the Imappivut Knowledge Study process, the research team held a series of meetings to make adjustments and suggestions to improve the framework. The research team also discussed the framework beyond the team to other Inuit and settler researchers and received more feedback. A second version of the framework was created based on these discussions. The framework includes broad categories that will be identified in the interviews.

The step “developing a framework” is replaced in our method with workshopping to be explicitly collaborative. In this and the next step, “corroboration”, the research team went through many iterations of a framework before the final version was “developed”. All team members were deeply familiar with the interview data, which made for rich conversations about how and why each category should be included or refined. The team also consulted with experts from outside the team, with skills and experience in both academia and community-based research to connect the framework more broadly with other ongoing research and to make sure the project would be relevant for the research community.

Corroboration and calibration

This step does not appear in the original Framework Method. In our work, once the framework was developed, visiting researcher Cadman and Labrador Inuk researcher Dicker selected one interview and together went through the first iteration of the coding process, discussing the relevance of the established framework and adding subcodes as they emerged. Dicker and Cadman coded to capture stories or ideas comprehensively, keeping them as complete as possible, which sometimes led to large sections of an interview captured in a single code (Hallett et al. 2017). As far as possible, Cadman and Dicker developed consensus on a final version of the framework. Cadman and Dicker then selected a second interview. They each coded the interview separately, then compared their coding and discussed any variations or disagreements.

Indexing

In the original method, the researchers identify portions of the data that correspond to the framework. Data are sorted into the categories that were developed in steps 1 and 2. In the Imappivut Knowledge Study analysis, Cadman and Dicker split up the interviews and coded them separately using qualitative analysis software NVivo. Coding files were merged daily to update the complete list of codes. During analysis, Cadman and Dicker worked closely together to discuss questions and problems as they emerged. They also conferred with research leaders in the Nunatsiavut Government daily. Cadman recorded conversations, observations, and questions in a research journal so there is a record of the iterative learning process the whole team underwent during this period. During this process, 173 subcodes were added, over half of which (106) referred to species.

A final version of the coding framework, developed inductively and iteratively, included the categories as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

| Broad code | Examples of subcodes |

|---|---|

| Activities | Egging, fishing, recreation, hunting |

| Cultural features | Cooking, keeping dogs, sharing |

| Landscape features | Ice, islands, polynyas |

| Made places | Cabins, trails, English River counting fence |

| Modes of transportation | Boat, skidoo, walking |

| Place names | (Place names were not given individual subcodes) |

| Seasonality | Early spring, spring, summer, early fall |

| Species | Berries, ducks, seals |

| Weather | Fog, rain, wind |

Filtering

This step does not occur in the original method. In our analysis, once all the interviews were indexed, the research team met to discuss the findings. The team noted that while all the codes can be considered important for Imappivut, there were certain aspects that study participants spoke about much more frequently than others. We interpret this to mean that these were things participants wanted to emphasize in answer to the question “how do you use and value the marine environment”. We identified the most frequently mentioned species and places in the data. To the initial list of six most frequently mentioned species, we added two species that had fewer codes attributed to them, but which Inuit team members identified as also being particularly culturally important. For example, caribou was added to the list because team members felt that the hunting ban on the George River caribou herd had limited the number of mentions, though it was still an important species. The research team agreed that these are culturally significant species and places in Nunatsiavut, which we referred to as cultural keystone resources (Garibaldi and Turner 2004). All of the codes pertaining to the cultural keystone species and places were pulled from the interviews and grouped together, resulting in 12 topics that were identified for qualitative analysis.

Charting

In the original method, data are lifted out of their context, collected, and placed into charts or groups for reporting on the results. We executed this step by having researchers Cadman and Dicker split up the 12 topics and each perform a detailed qualitative analysis to identify the key characteristics, themes, and connections found within each. Their observations were recorded into Microsoft Word documents. These detailed analyses for each topic are known in the Framework Method as “charts”. The charts were exchanged among the researchers and the data were analyzed again, tracking comments or additions to each other's work using the track changes function. Finally, team lead Denniston reviewed all 12 charts, adding questions and comments that helped to clarify the results and add context to the findings.

Mapping and interpretation

In the original method, researchers then pull out key characteristics of the themes to help describe and define them. The researchers are looking for attributes and connections between the themes that help to create a kind of map or schematic explanation of the data. Ritchie and Spencer describe this as “defining concepts, mapping range and nature of phenomena, creating typologies, finding associations, providing explanations, and developing strategies” (Ritchie and Spencer 1994, pp. 186). Having developed an understanding of the individual species and places of importance, the research team met to discuss connections and themes emerging from the process. The team identified four overarching themes and discussed definitions and visualizations to communicate the ideas.

Results

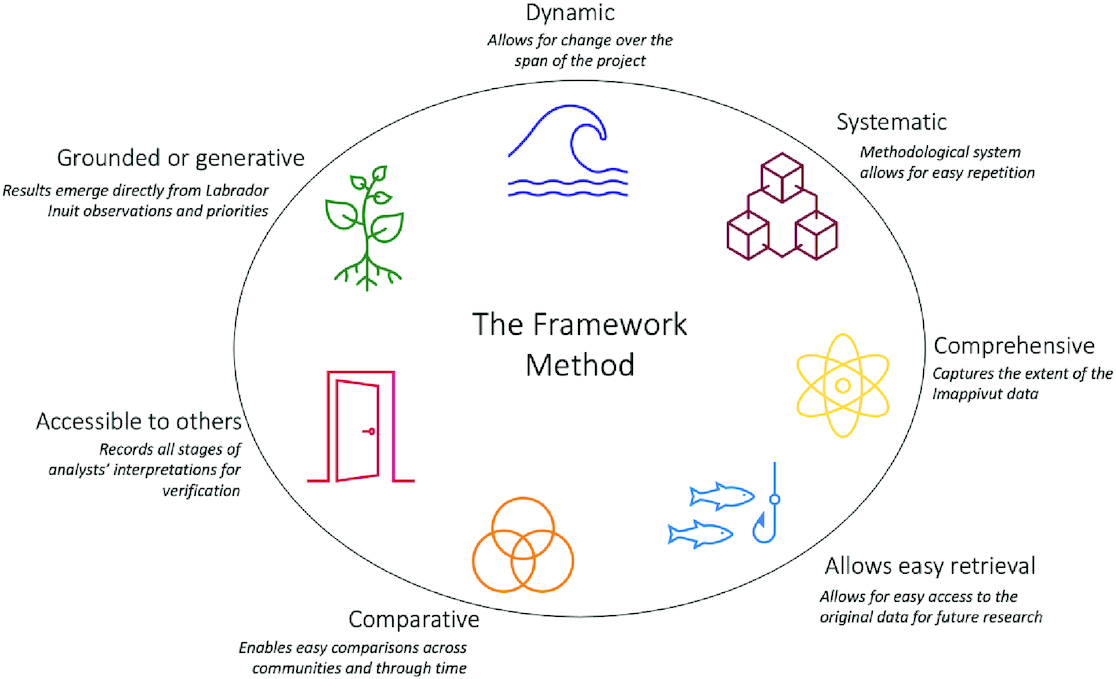

Some of the key features of the Framework Method were particularly relevant for the Imappivut research objectives listed above. Using a table adapted from Ritchie and Spencer (1994), we offer some reflections on what made this method particularly useful for collaborative cross-cultural data analysis (see Table 2).

Table 2.

| Key feature | Definition | Why it is relevant for Imappivut |

|---|---|---|

| Grounded or generative | Heavily based in, and driven by, the original accounts and observations of the people it is about | The intent of the Imappivut analysis is to have the results emerge directly from the words and ideas of Labrador Inuit |

| Dynamic | Open to change, addition, and amendment throughout the analytic process | The analysis occurred on the first stage of data collection, but there will be more data added in the future. This method allows for subsequent analysis to be folded into the same project |

| Systematic | Allows methodical treatment of all similar units of analysis | While this initial analysis focused on the most significant and frequently mentioned elements of life in Nunatsiavut, this method of sorting data makes it easy for future analysts to access all units (or nodes) for the same process of analysis |

| Comprehensive | Allows a full, and not partial or selective, review of the material collected | This method allows for a full inventory to be taken of the data so that the interviews can be seen holistically. This helps to minimize bias between analysts, because even if one analyst has decided that certain elements of the data are “more important” than others, they are unable to ignore or erase those elements |

| Enables easy retrieval | Allows access to, and retrieval of, the original textual material | The primary analysts working on the first stage of this project were not full-time permanent employees of the Nunatsiavut Government. It was important to find a method that would organize and preserve the data in an accessible way for future research |

| Allows between- and within-case analysis (comparative) | Enables comparisons between, and associations within, cases to be made | This method allowed for an analysis between communities that can reveal some of the features that are unique to each community, as well as to understand what was common across the region |

| Accessible to others | The analytic process, and the interpretations derived from it, can be viewed and judged by people other than the primary analyst | The Imappivut project is intended to be evergreen and collect data far into the future. There is a high likelihood that the individuals completing this project will change over time because of staff turnover. This method allows for new interventions at multiple points in the analysis process and records the thinking of the analyst throughout. New researchers will be able to review the data in ways that allow not only a detailed understanding of its features but also for evolution of the results over the years |

We further examine the extent to which the Framework Method supported the three goals of the project:

1.

To create an inventory of the data. The Framework Method begins with an indexing process, which allowed us to create a thorough inventory of the data. Though we started out with an assumed list of categories for the data, we soon found that those categories shift to better reflect both the content of the interviews, and the aspects of it that Inuit analysts identified as being important. The dynamic nature of the process was essential for this. For example, Dicker identified that place names were significant data that should be collected as their own category, prompting the team to add this category to the index and review the data. Denniston taught us that “species” identification was not always the way that Inuit distinguished animals and plants. Seals, for example, might be distinguished by their age and sex rather than their species. The original categories for various species of seal were amalgamated and redistributed to better represent a Labrador Inuit understand of this genus. Thus, the resulting inventory is grounded in the information shared by knowledge holders on the team. This index is comprehensive, identifying as much information about individual species, activities, and places as possible.

2.

To identify the values and needs of Nunatsiavut beneficiaries that will guide conservation and management in the marine environment. The goals of the Imappivut Marine Plan are oriented around identifying a collection of Inuit values, uses, and Traditional Knowledge to support environmental policy and conservation for Nunatsiavut and its adjacent waters, and to safeguard Labrador Inuit culture. It was necessary to use a method that could deliver practical and useable results for that purpose. The Framework Method presented a systematic and comprehensive way for the Nunatsiavut Government to run further inquiries and apply the information to specific policy-related research questions. The results also provided information about cultural keystone species (Garibaldi and Turner 2004). The analysis recorded here established the importance of multiple species of plants and animals that have significance for Labrador Inuit livelihoods, food security, spirituality, and sense of well-being. Identifying these species as priorities for management is a practical and immediate result for Nunatsiavut decision-makers.

3.

To highlight priorities for future research. As this project is ongoing, each new participant will always add something valuable for the Imappivut Marine Planning Initiative, whether it is an observation, a research question, or a story. This project used an unstructured method to solicit information from participants, which led to a rich dataset that covered innumerable topics related to the coastal and marine environments. Analysis identified several new questions and concerns held by the participants that can be quickly integrated into new and current research programs, allowing them to be comparative with any new data. For example, concerns around Arctic char stocks recorded in the interviews helped the Nunatsiavut Government to direct a number of new research programs dedicated to studying char. In general, these priorities were already known to Inuit researchers, either because they had participated in the original data collection, or because as members of their community they were intimately familiar with these concerns. The value of this analysis was not in finding theretofore unknown issues, it was in pulling a wide ranging and diverse set of priorities into an actionable list for the Nunatsiavut Research Centre.

Discussion

The Framework Method had important qualities that made it well suited for analysis in support of the Imappivut Knowledge Study—it was systematic, comprehensive, and dynamic; the results emerged directly from Labrador Inuit priorities; and the outcomes were accessible, comparable, and easy to retrieve (see Fig. 2). The steps outlined above may prove useful for other researcher groups who seek capacity-sharing approaches in support of ethical collaborative research that can draw from Western and Indigenous knowledge systems to generate a collective wisdom (Kimmerer 2018). In this section, we reflect on how this experience connects with the broader literature on collaborative research.

Fig. 2.

The integration of multiple knowledge systems

We understand Labrador Inuit Knowledge, like all Indigenous Knowledges, to be a complete knowledge system (Latulippe and Klenk 2020; Pedersen et al. 2020). It is a way of governing, relating to, and understanding the world that is bound up with the lands and waters of Nunatsiavut. The interviews conducted during the Imappivut Knowledge Study provide a window into that complex knowledge system. In bringing multiple perspectives to coproduce the analysis, our team's goal was to create practical knowledge, grounded in its context and for the benefit and advancement of Labrador Inuit. But bringing together multiple knowledge systems in research requires specific consideration of not only the outcomes of the research but also the processes of knowledge coproduction (Bull 2010; Petriello et al. 2022; Zurba et al. 2022). The Framework Method gave us an opportunity to work creatively and collaboratively and produce something that would not have been achieved through the application of one knowledge system alone (Ellam Yua et al. 2022).

At the core of the Framework Method is its iterative, collaborative coding process. The method was designed with several steps to encourage greater reflexivity and evaluation to occur throughout the coding process (Hallett et al. 2017; Waddell-Henowitch et al. 2022). It was considered important that the method be inductive to allow for open, collaborative conversation and the incorporation of insights from Western and Inuit knowledge systems. Understanding complexity and connections within a system requires an element of openness to learning and discovery (Wilson 2008). An inductive method of inquiry was better suited to allowing for results to emerge from collective conversation and multiple perspectives on the material.

The framework is essentially a reductive process, which requires the analysts to separate out ideas and stories from their context and from the individual storyteller. The method therefore remains couched in a Western knowledge paradigm and should not be considered an “Indigenous methodology”. Still, because the process emerged from our team conversations, Inuit team members were continually recontextualizing the codes. The “data” in the interviews were never just a list of facts. They were interpreted through additional rules and obligations expressed by the Inuit team members, connecting our findings to the welfare, well-being, and resilience of the land and communities. An example of this was a conversation about White ptarmigan (AKiggik) hunting, which started when Denniston took issue with an observation in the analysis that much of the hunting spoken about in the interviews took place near rivers, in the brush. This prompted a group discussion, which led to Inuit team members and other employees at the Nunatsiavut Research Centre sharing hunting stories and observations, and eventually led the team to realize that AKiggik hunting had been increasing in the region since a moratorium had been placed on hunting caribou in 2013, and helped us to recontextualize the AKiggik hunt in terms of its connections to conservation and food security, and remind us of what was at stake in this research. Inuit approaches to interpreting and understanding this information are about how they engage with the stories and their relationships to it (Ljubicic et al. 2018). The design of this method, particularly its iterative and discursive quality, was instrumental to bringing our two understandings together to enrich the final product.

Data sovereignty

The National Inuit Strategy on Research (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami 2018) established that Inuit must have control over data collected in Inuit Nunangat. Issues of control over research and data are a primary concern to Indigenous nations around the world, and indeed are implicated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (Kukutai and Taylor 2016; UNDRIP 2007). Definitions and applications of data sovereignty are relatively new, and explicit processes and frameworks are needed to support Indigenous Peoples in gaining control over data. Snipp (2016) proposes that data sovereignty requires that Indigenous Peoples have the power to define their communities, that research must reflect their own priorities, and that their communities control access to the data in perpetuity. Carroll et al. (2019) note that this will require significant capacity for the management, security, and storage of the data. This should be extended to every part of the research process, so that the work itself helps to grow capacity in support of data sovereignty.

One advantage of the Framework Method is the construction of an index that provides a high-level overview of what is included in the data, and the ability to quickly pull information related to any specific topic. The index helps Nunatsiavut to maintain control over access to the data, one of the essential preconditions to data sovereignty. To date, the Imappivut interviews contain the views of 54 participants from across Nunatsiavut, representing approximately 100 h of interview time. There is a lot of personal information in those interviews, as each participant shared their stories and experiences in their own unique way, and therefore, protection of personal information is paramount. Research like the Imappivut Knowledge Study handles data that could have unforeseen and negative consequences on communities if released, such as deeply held cultural and spiritual values, or potentially sensitive information about harvesting areas, which may lead the Inuit community to not wish to release data in its entirety. The “indexing” step of the Framework Method allows for the collection and sorting of all the information included in the interviews to make it accessible for future researchers and policy makers in the Nunatsiavut Government. This adds a fine-scale level of control to the distribution and use of potentially sensitive data. For example, a visiting researcher interested in Arctic char may be given only those codes relating to Arctic char. This is an important example of developing research capacity, built directly into the analysis stage of the research process (Huria et al. 2019).

We note that maintaining the data index requires that the Nunatsiavut Research Centre keep up its NVivo licence indefinitely, which puts a limit on the usefulness of this tool. We have completed Microsoft Word documents that gather important information together for each of the cultural keystone species and the important spaces, and these would provide an easy way of maintaining access to those elements of the data to mitigate this problem. Future work could include expanding this part of the analysis to other elements of the data.

On mixing the personal and professional

Working with these data was a humbling experience. It offered an opportunity for our research team to share our expertise and experiences as they related to the stories told by Labrador Inuit participants and methods of analyzing those stories. The Framework Method, in and of itself, provides a useful tool for cross-cultural collaboration in data analysis, but, like the Imappivut data, it is important to contextualize the process and the experiences of this research team to understand its success. The fact that the analysis took place in Nunatsiavut and emphasized relationship building, mutual learning and accountability was essential. We begin with brief individual reflections from Megan Dicker, Rachael Cadman, and Mary Denniston, the core analysts, on their experiences and what they learned:

Megan Dicker (Inuk/government researcher)

Taking part in the Imappivut analysis was both eye-opening and stimulating. The work that Cadman and I did complemented each other; I had the opportunity to share knowledge and insights into the work as a member of both my hometown and Nunatsiavut in general, and Cadman had the opportunity to share her skills and outlook from an outsider and academic perspective. Our knowledges combined filled gaps that would have been missed otherwise.It was interesting to see things that are normal for me in different ways. Take the stories and place them into datasets, such as “taking only what you need” when out on the land. I did not give this much thought up until then because it seemed as natural a thing as breathing or walking. Only after working on a team with visiting researchers, including Cadman, who asked questions and clarified things, did I begin to think about the information and priorities in the interviews in terms of how they could inform governance.

Rachael Cadman (settler/visiting researcher)

Being part of this analysis process changed my approach to research forever. I will be forever in debt to my colleague Dicker for gifting me the term “Inuk facts”, which not only gave me a wonderful way to describe the myriad of tidbits that came out of the Imappivut interviews (berries taste sweeter after a frost, porpoises jumping in the harbour are a sign that strong winds are coming, navigation on the water or ice requires looking back at where you came from), it also helped me to understand Inuit Knowledge as more than this collection of facts, but as a totality of relational, cultural, and spiritual beliefs. The layers of work that went into our analysis raised questions I never would have thought of on my own, and made this process a more personal, more human experience than I had had working with data before. Working on this team made me better suited to creating contextually relevant work that honours those who have taught me.

Mary Denniston (Inuk/government researcher)

The Imappivut vision is to ensure Inuit interests and priorities are at the forefront of decisions and planning. Working together with Cadman and Dicker, as well as other members of the research team, has definitely kept this vision as the focus. The commitment from everyone to ensure respect and understanding of Inuit ways of living and doing, of our culture and our language has helped our team do exceptional work. This has given me the belief and trust that we are moving away from the old way of doing research and that the rightful way can be achieved with hard work, the right people, and through respect and trust. Taking time to listen and understand what Inuit value and why is not a natural thing for outside researchers and academic institutions, but this work has proven that it is not impossible. The National Inuit Strategy on Research is a tool to ensure visiting researchers and Inuit are better equipped to do work that respects and accepts Inuit as rights holders, but it is the people who choose to see the value of this tool that ensures we are able to reach these goals. I have been involved in research in Nunatsiavut for 23 years, and this team achieved something I have not seen before: a process that truly represents our ways, our culture, and our struggle to hold on to our livelihood as Inuit, and the importance of ensuring we are able to carry this into the future using research to better inform Inuit and institutions in decisions that affect Inuit Nunangat.

We focus on the process of this research, rather than on the outcomes, because it highlights important ways that working together allow for our work to strengthen not only the results but also our capacities as researchers (Chapman and Schott 2020). This process allowed us to identify results that will be useful for future research, conservation, and management planning in Nunatsiavut, and it also provided an opportunity for personal growth and reflection. We were also able to identify our limitations in understanding a collection of knowledge that ranged widely between individuals and communities. Many have pointed out before that successful knowledge coproduction requires developing relationships and grounding in place (Leeuw et al. 2012; Carlson 2017; Carter et al. 2019; Petriello et al. 2022). We found the Framework Method supported learning and open discussion because of its iterative nature, which made relationship building possible.

However, we also share these personal reflections to qualify the success of the method and to put it into context. A cookie cutter replication of the method alone would not achieve the same results. This analysis was conducted amid months of tea and debates over whether black bear was a tasty meat. It was put on hold when the weather was good enough to get out in a boat for the day. Community members popping into the research center provided clarification on terminology for different kinds of ice formation. The entirety of this process of storytelling, interpretation, and reinterpretation occurred in a building the community knows to be haunted. In other words, the success of this method also relied on grounding it in place and allowing the process to unfold organically.

Conclusion

The National Inuit Strategy on Research (Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami 2018) prioritizes the need for Inuit to lead research grounded in regional priorities, develop research capacity within their regions, and take an active role in data sovereignty issues. The Imappivut Knowledge Study supports this goal by collecting information from Labrador Inuit about how their coastal and marine environment should be governed. This rich and complex data will support the Nunatsiavut Government in developing marine governance and future research that is strongly rooted in Labrador Inuit Knowledge and community priorities alongside Western scientific understandings of the marine environment.

In support of that goal, this collaborative initiative between Nunatsiavut Government researchers and academic researchers based in Halifax, Nova Scotia sought to catalogue and analyze the data in ways that support Nunatsiavut sovereignty (Carroll et al. 2019). The Framework Method was a useful tool for collaborative data analysis. It supported the three goals of this project: to create an inventory of the data, to identify the values and needs of Labrador Inuit for policy making, and to highlight priorities for future research. The method is based on indexing the data, which we found supports Nunatsiavut's control over the research for easy referencing, privacy, and management. The highly iterative process we added to the method aided us in bringing together two disparate ways of knowing to emphasize information on priority species, activities, and places. And our emphasis on place and relationships grounded the process and the outcomes.

Over the last few decades, academic interest in Indigenous Knowledge and collaborative research has grown exponentially, and methods for ethical, meaningful, decolonial engagement between Western academic researchers and Indigenous researchers and communities are still being developed. A data analysis method like the one used in this research and discussed here is not a guarantee that research is ethical, meaningful, or decolonial. Indeed, this collaborative Framework Method relies on the dominant Western academic expectations of research and, therefore, cannot be entirely decolonial (Tuck and Yang 2012; Liboiron et al. 2021b). However, with intention, humility, and honest conversation, the Framework Method can be a tool to support greater data sovereignty and evidence-based decision-making for Inuit and create opportunities for mutual learning and capacity sharing, which are all key steps toward improving the decolonial capacities of research.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the participants of this study with thanks and particularly appreciate the hospitality of the Nunatsiavut Government Research Centre, which made this research possible. Many people contributed to the Imappivut Knowledge Study, in particular researchers Eldred Allen, Chaim Andersen, Katrina Anthony, Caroline Nochasak, and Rudy Riedelsperger. This study was supported by a Canada First Research Excellence Fund grant through the Ocean Frontier Institute. RC acknowledges support from a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) doctoral award.

References

Beveridge R., Moody M., Pauly B., Murray G., Darimont C. 2021. Applying community-based and Indigenous research methodologies: lessons learned from the Nuxalk Sputc Project. Ecology and Society, 26(4).

Breton-Honeyman K., Furgal C.M., Hammill M.O. 2016. Systematic review and critique of the contributions of traditional ecological knowledge of beluga whales in the marine mammal literature. Arctic, 69(1): 37–46. Canadian Business & Current Affairs Database.

Brunger F., Wall D. 2016. “What do they really mean by partnerships?” Questioning the unquestionable good in ethics guidelines promoting community engagement in Indigenous health research. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13): 1862–1877.

Bull J.R. 2010. Research with Aboriginal peoples: authentic relationships as a precursor to ethical research. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 5(4): 13–22.

Carlson E. 2017. Anti-colonial methodologies and practices for settler colonial studies. Settler Colonial Studies, 7(4): 496–517.

Carroll S.R., Rodriguez-Lonebear D., Martinez A. 2019. Indigenous data governance: strategies from United States native nations. Data Science Journal, 18: 31.

Carter N.A., Dawson J., Simonee N., Tagalik S., Ljubicic G. 2019. Lessons learned through research partnership and capacity enhancement in Inuit Nunangat. Arctic, 72(4): 381–403.

Castleden H., Morgan V.S., Lamb C. 2012. “I spent the first year drinking tea”: exploring Canadian university researchers’ perspectives on community-based participatory research involving Indigenous peoples. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 56(2): 160–179.

Chambers J.M., Wyborn C., Klenk N.L., Ryan M., Serban A., Bennett N.J., et al. 2022. Co-productive agility and four collaborative pathways to sustainability transformations. Global Environmental Change, 72: 102422.

Chapman J.M., Schott S. 2020. Knowledge coevolution: generating new understanding through bridging and strengthening distinct knowledge systems and empowering local knowledge holders. Sustainability Science, 15(3): 931–943. Earth, Atmospheric & Aquatic Science Collection.

Cunsolo Willox A., Harper S.L., Ford J.D., Landman K., Houle K., Edge V.L. 2012. “From this place and of this place:” climate change, sense of place, and health in Nunatsiavut, Canada. Social Science & Medicine, 75(3): 538–547.

Ferrazzi P., Christie P., Jalovcic D., Tagalik S., Grogan A. 2018. Reciprocal Inuit and Western research training: facilitating research capacity and community agency in Arctic research partnerships. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 77(1): 1425581.

Garibaldi A., Turner N. 2004. Cultural keystone species: implications for ecological conservation and restoration. Ecology and Society, 9(3).

Hallett J., Held S., McCormick A.K.H.G., Simonds V., Real Bird S., Martin C., et al. 2017. What touched your heart? Collaborative story analysis emerging from an Apsáalooke cultural context.Qualitative Health Research, 27(9): 1267–1277.

Hayward A., Cidro J., Dutton R., Passey K. 2020. A review of health and wellness studies involving Inuit of Manitoba and Nunavut. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 79(1): 1779524.

Held M.B.E. 2020. Research ethics in decolonizing research with Inuit communities in Nunavut: the challenge of translating knowledge into action. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19: 1609406920949803.

Henri D.A., Carter N.A., Irkok A., Nipisar S., Emiktaut L., Saviakjuk B., et al. 2020. Qanuq ukua kanguit sunialiqpitigu? (What should we do with all of these geese?) Collaborative research to support wildlife co-management and Inuit self-determination. Arctic Science, 6(3): 173–207.

Huria T., Palmer S.C., Pitama S., Beckert L., Lacey C., Ewen S., Smith L.T. 2019. Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples: the CONSIDER statement. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1): 173.

Inuit Circumpolar Council. 2021. Ethical and equitable engagement synthesis report: a collection of Inuit rules, guidelines, protocols and values for the engagement of Inuit Communities and Indigenous Knowledge from across Inuit Nunaat. Inuit Circumpolar Council. Available from https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/project/icc-ethical-and-equitable-engagement-synthesis-report/.

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. 2018. National Inuit Strategy on Research. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami.

Kimmerer R.W. 2018. Mishkos Kenomagwen, the lessons of grass: restoring reciprocity with the Good Green Earth. In Traditional ecological knowledge: learning from indigenous practices for environmental sustainability. Edited by M.K. Nelson, D. Shilling. Cambridge University Press.

Kukutai T., Taylor J. (Editors). 2016. Indigenous data sovereignty: toward an agenda. ANU Press.

Latulippe N. 2015. Bridging parallel rows: epistemic difference and relational accountability in cross-cultural research. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 6(2). PAIS Index.

Latulippe N., Klenk N. 2020. Making room and moving over: knowledge co-production, Indigenous knowledge sovereignty and the politics of global environmental change decision-making. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 42: 7–14.

Leeuw S., Cameron E.S., Greenwood M.L. 2012. Participatory and community-based research, Indigenous geographies, and the spaces of friendship: a critical engagement. Canadian Geographies/Les Géographies Canadiennes, 56(2): 180–194.

Liboiron M. 2021a. Pollution is colonialism. Duke University Press.

Liboiron M. 2021b. Decolonizing geoscience requires more than equity and inclusion. Nature Geoscience, 14(12): 876–877.

Ljubicic G., Okpakok S., Robertson S., Mearns R. 2018. Inuit approaches to naming and distinguishing caribou: considering language, place, and homeland toward improved co-management. Arctic, 71(3).

McGregor D., Bayha W., Simmons D. 2010. “Our responsibility to keep the land alive”: voices of Northern Indigenous researchers. 24.

Norström A.V., Cvitanovic C., Löf M.F., West S., Wyborn C., Balvanera P., et al. 2020. Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nature Sustainability, 3(3).

Pedersen C., Otokiak M., Koonoo I., Milton J., Maktar E., Anaviapik A., et al. 2020. ScIQ: an invitation and recommendations to combine science and Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit for meaningful engagement of Inuit communities in research. Arctic Science, 6(3): 326–339.

Petriello M.A., Zurba M., Schmidt J.O., Anthony K., Jacque N., Nochasak C., et al. 2022. The power and precarity of knowledge co-production. In Transdisciplinary marine research. 1st ed. Edited by S. Gómez, V. Köpsel. Routledge. pp. 127–148.

Read S., Ashman M., Scott C., Savage J. 2004. Evaluation of the modern matron role in a sample of NHS trusts. p. 225. The Department of Health Policy Research Programme.

Reid A.J., Young N., Hinch S., Cooke S. 2022. Learning from Indigenous knowledge holders on the state and future of wild Pacific salmon. FACETS, 7(1). https://www.facetsjournal.com/doi/full/10.1139/facets-2021-0089

Ritchie J., Spencer L. 1994. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Analyzing qualitative data. Edited by A. Bryman, B. Burgess. Routledge.

Sawatzky A., Cunsolo A., Jones-Bitton A., Gillis D., Wood M., Flowers C., et al., & The Rigolet Inuit Community Government. 2020. “The best scientists are the people that's out there”: Inuit-led integrated environment and health monitoring to respond to climate change in the Circumpolar North. Climatic Change, 160(1): 45–66.

Snipp C.M. 2016. What does data sovereignty imply: what does it look like? In Indigenous data sovereignty: toward an agenda, Vol. 38. Edited by T. Kukutai, J. Taylor. ANU Press. pp. 39–56Http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1q1crgf.10.

Srivastava A., Thomson S.B. 2009. Framework analysis: a qualitative methodology for applied policy research. Journal of Administration and Governance, 4(2): 72–79.

Tester F.J., Irniq P. 2008. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: social history, politics and the practice of resistance. Arctic, 61: 48–61. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40513356.

Todd Z. 2016. An Indigenous feminist's take on the ontological turn: ‘ontology’ is just another word for colonialism. Journal of Historical Sociology, 29(1): 4–22.

Tuck E., Yang K.W. 2012. Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1): 1–40.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: resolution adopted by the General Assembly. 2007. UN General Assembly; A/RES/61/295. Available from https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html.

Waddell-Henowitch C., Gobeil J., Tacan F., Ford M., Herron R.V., Allan J.A., et al. 2022. A collaborative multi-method approach to evaluating Indigenous land-based learning with men. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21: 160940692210823.

Watts V. 2013. Indigenous place-thought and agency amongst humans and non humans (First Woman and Sky Woman go on a European world tour!). Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 2(1). Available from https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/19145.

Whyte K. 2018. What do Indigenous Knowledges do for Indigenous Peoples? In Traditional ecological knowledge: learning from Indigenous practices for environmental sustainability. Edited by D. Shilling, M.K. Nelson. Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–82.

Williams L. 2018. Ti wa7 szwatenem. What we know: Indigenous knowledge and learning. B.C. Studies, 200, 14.

Wilson S. 2008. Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Publishing.

Youngblood Henderson J. (Sa’ke’j). 2019. The art of braiding Indigenous peoples’ inherent human rights into the law of nation states. In Braiding legal orders: implementing the United Nations declaration on the rights of Indigenous Peoples. Edited by J. Borrows, L. Chartrand, O.E. Fitzgerald, R. Schwartz. Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Yua E., Raymond-Yakoubian J., Daniel R.A., Behe C. 2022. A framework for co-production of knowledge in the context of Arctic research. Ecology and Society, 27(1): art34.

Zurba M., Petriello M.A., Madge C., McCarney P., Bishop B., McBeth S., et al. 2022. Learning from knowledge co-production research and practice in the twenty-first century: global lessons and what they mean for collaborative research in Nunatsiavut.Sustainability Science, 17(2): 449–467.

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

FACETS

Volume 8 • 2023

Pages: 1 - 13

Editor: Idil Boran

History

Received: 29 June 2022

Accepted: 3 April 2023

Version of record online: 3 July 2023

Copyright

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated or analyzed during this study are owned by the Nunatsiavut Government and remain with the knowledge holders and communities that participated in this work. Access to data generated and analyzed during this work will be determined by the Nunatsiavut Government Research Advisory Committee on behalf of those communities.

Key Words

Sections

Subjects

Authors

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: MD, PM, RL, ECJO, MB

Data curation: RC, MD, MD, PM

Formal analysis: RC, MD, MD, PM

Funding acquisition: PM, RL, ECJO, MB

Investigation: MD, PM

Methodology: RC, MD, MD, PM, MB

Project administration: PM, RL, ECJO, MB

Resources: RL, ECJO, MB

Supervision: PM, RL, ECJO, MB

Validation: RC, MD, MD, PM, RL

Visualization: RC, MB

Writing – original draft: RC, MD, MD

Writing – review & editing: RC, MD, MD, PM, RL, ECJO, MB

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Other Metrics

Citations

Cite As

Rachael Cadman, Megan Dicker, Mary Denniston, Paul McCarney, Rodd Laing, Eric C.J. Oliver, and Megan Bailey. 2023. Using the Framework Method to support collaborative and cross-cultural qualitative data analysis. FACETS.

8: 1-13.

https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2022-0147

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

Cited by

1. Addressing the legacy of past mining in the Garden River First Nation Community: Perspectives and pathways to improve community engagement

2. Understanding the Impacts of Arctic Climate Change Through the Lens of Political Ecology