Introduction

Resilience theory is useful for understanding how environmental and policy change will impact resource users. The concept of resilience is rooted in ecological literature, where it describes the capacity of an ecosystem to persist in a stable state despite being subject to disturbance (

Holling 1973;

Holling et al. 1995). More recently, resilience theory has been adopted in the study of coupled human and natural systems, referred to as social–ecological systems (SESs;

Folke 2006;

Gallopín 2006;

Walker et al. 2006;

Engle 2011). Resilient SESs are often characterised by diversity in terms of species, human opportunities, and economic possibilities (

Folke et al. 2002;

Henry and Johnson 2015). SESs with higher resilience can tolerate larger disturbances—political or environmental—without fundamentally changing and are flexible, adaptable, and prepared for the possibility of transformation (

Gunderson 1999;

Folke et al. 2002). In contrast, non-resilient SESs are susceptible to irreversible and catastrophic change (

Marshall and Marshall 2007). A core component of SES resilience is social resilience (SR), which is the ability of groups or communities to cope with, or adapt to disturbances related to social, political, and environmental change (

Adger 2000). SR is inherently connected to the concept of vulnerability, which is the state of susceptibility to harm imposed by environmental and social change (

Adger 2006).

SR is widely recognised as a composition of several underlying attributes and processes that enable people and their respective SESs to successfully cope with and adapt to change or crises (

Maclean et al. 2014). Attributes of SR can be conceptualised and measured at both community and individual scales. For instance,

Maclean et al. (2014) describe community-scale SR as including: (1) knowledge, skills, and learning; (2) community networks; (3) people–place connections; (4) community infrastructure; (5) diverse and innovative economies; and (6) engaged governance. An important consideration is that community-scale analyses may risk concealing core resilience properties that predict how individuals within communities will respond to and be impacted by changes in access to natural resources. Therefore, understanding social resilience at the individual scale is crucial (

Marshall and Marshall 2007;

Sutton and Tobin 2012).

Marshall and Marshall (2007) conceptualise individual-scale SR as including: (1) perception of risk associated with change; (2) perception of the ability to plan, learn, and reorganise; (3) perception of the ability to cope; and (4) level of interest in change. The same authors developed a 12-item survey tool for measuring individual-scale social resilience in natural resource management settings.

There is a growing recognition of the role that socio-cognitive attributes play in contributing to the SR of resource-dependent individuals. This includes risk perceptions—the subjective judgments individuals make about the likelihood of negative environmental or policy changes and the severity of harm they may cause (

Darker 2013;

McClenachan et al. 2020). Cognitive biases formed through previous experience of environmental or policy change have been shown to influence risk perceptions to either help build or erode levels of preparedness for future change (

Cinner and Barnes 2019). Optimism biases may lead individuals to underestimate personal risk of change and take inadequate adaptive measures (

Mortreux and Barnett 2017). Additionally, trust in resource governance institutions can be important for adaptation, with both high and low trust leading to poor adaptation outcomes (

Stern and Coleman 2015). For instance, high levels of trust in institutions have been associated with complacency in the face of environmental change, whereas low trust can lead to non-compliance with institutional advice (

Mortreux and Barnett 2017).

SR is critically important for fishing communities, which are considered highly vulnerable due to their reliance on fishery resources, and their exposure to coastal hazards (

Adger et al. 2005;

Marshall et al. 2007). Flexibility often plays a key role in enabling fishers’ adaptation to change. For instance, fishers may exhibit flexibility by establishing alternative economic ventures outside of fishing, or by diversifying the fisheries they partake in (

Finkbeiner 2015;

Henry and Johnson 2015;

Belhabib et al. 2016;

Mohamed Shaffril et al. 2019). Adaptation can also be linked to the degree of engagement in management and decision-making processes, with those least engaged being most vulnerable to change (

Cinner et al. 2015). However, fishers’ resilience may ultimately be constrained by structural factors: obstinate societal features, such as policies, procedures, and infrastructure (

Stoll et al. 2021;

Maltby et al. 2023). For example, engagement with decision-making processes may be limited by centralised management structures (

Armitage et al. 2009), and flexibility may be hampered by high costs of access to alternative fisheries (

Carothers 2015).

Research aims

In Canadian fisheries, prior research has underscored the need for a better incorporation of human dimensions data—including fishers’ socioeconomic concerns—in fisheries decision-making (

Stephenson et al. 2019; Foley et al. 2020;

Harper et al. 2023). At the same time, the concept of SR has shown promise as an analytical framework, providing an opportunity to help identify and mitigate potentially detrimental effects of change on vulnerable individuals and communities (

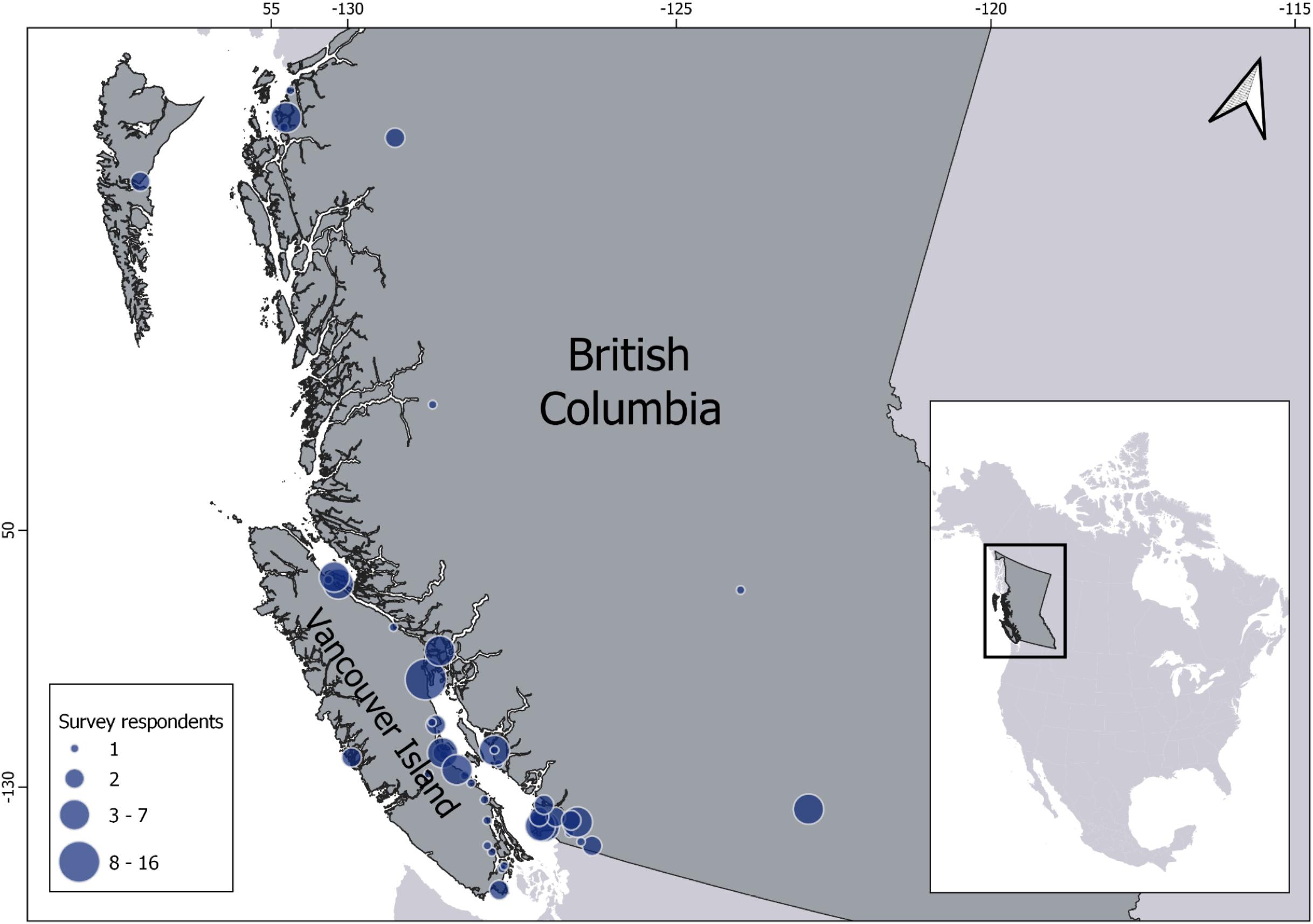

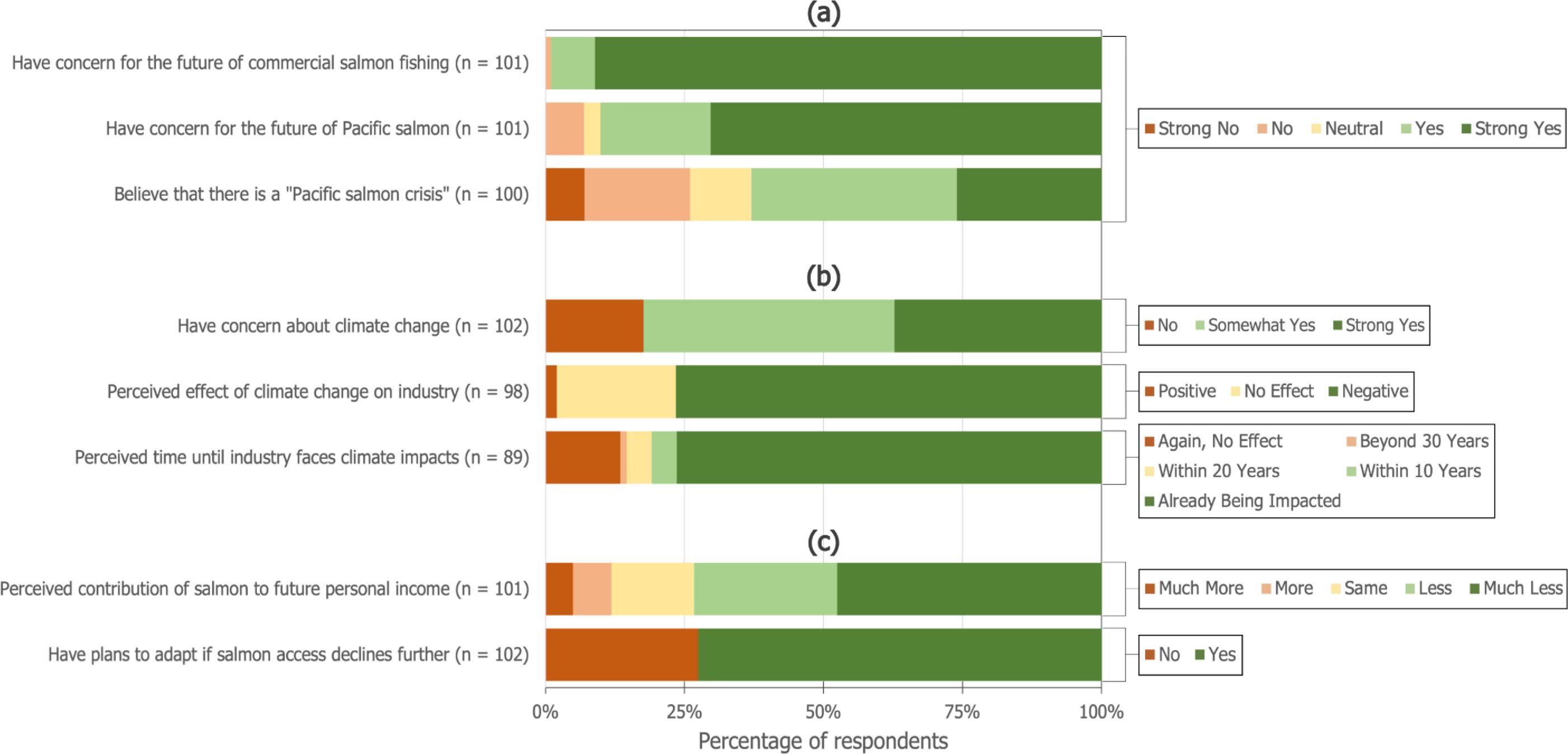

Sutton and Tobin 2012). Here, using British Columbia’s (BC’s) commercial salmon fishery as a case study, we integrated

Marshall and Marshall's (2007) 12-item tool with a survey instrument to measure fishers’ individual-scale SR and explore their concerns for the industry’s future. Additionally, in-depth interviews were used to contextualise select aspects of our survey results. We aim to advance community objectives of identifying socioeconomic dimensions of vulnerability in BC commercial salmon fisheries whilst contributing to the greater body of resilience knowledge. Our research builds on prior analyses that have examined the relationships between commercial fishers’ social resilience and policy perceptions (e.g.,

Marshall 2007;

Sutton and Tobin 2012), advancing the field by exploring how SR relates to socioeconomic characteristics, trust in management, and perceptions of risk.

BC’s salmon fishing landscape

In BC, Canada, the commercial Pacific salmon (

Oncorhynchus spp.; hereafter salmon) fishery includes small boat (gillnet, troll) and large boat (seine) fisheries. The commercial fishery is one of three sectors vying for access to salmon, which also include the recreational fishery—the largest sector by number of participants—and the Indigenous food, social, ceremony (FSC) fishery. The FSC fishery is intended to ensure Indigenous communities can meet food security and cultural needs and is therefore given first priority in accessing salmon after conservation needs have been met. FSC licences are communal and prohibit the sale of catch. While the FSC fishery is not the subject of this paper, it is important to note that for many Indigenous fishers, participation in the FSC fishery is contingent upon earning enough take-home profit from the commercial fishery to maintain their vessels and equipment (

Burke 2010). Due to the transboundary nature of salmon migration, and requirements set by the Pacific Salmon Treaty, US fishers also access Canadian-bound salmon, which are now considered to be “over-subscribed” (

Nelson and Turris 2004).

The decline of salmon and the commercial salmon fishery

The abundance of wild-origin salmon across the Pacific Northwest has been in a marked decline since the 1960s despite efforts by both US and Canadian governments to conserve salmon and enhance stocks through the release of millions of hatchery-raised fish (

Nelson and Turris 2004). Declines have been driven by the cumulative effects of overfishing, forestry, damming, irrigation, pollution, gene dilution, and climate change (

Nehlsen et al. 1991;

Bradford and Irvine 2000;

Mann and Plummer 2000;

Lichatowich 2001;

Quinn 2018;

Crozier et al. 2021). By the early 1990s, worsening declines—particularly for several BC, Washington, Oregon, and California Chinook (

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) and Coho (

O. kisutch) stocks—signalled a major crisis, sometimes called “the Pacific salmon crisis” (

Noakes et al. 2000;

Lichatowich 2001;

Nelson and Turris 2004;

Walters et al. 2019).

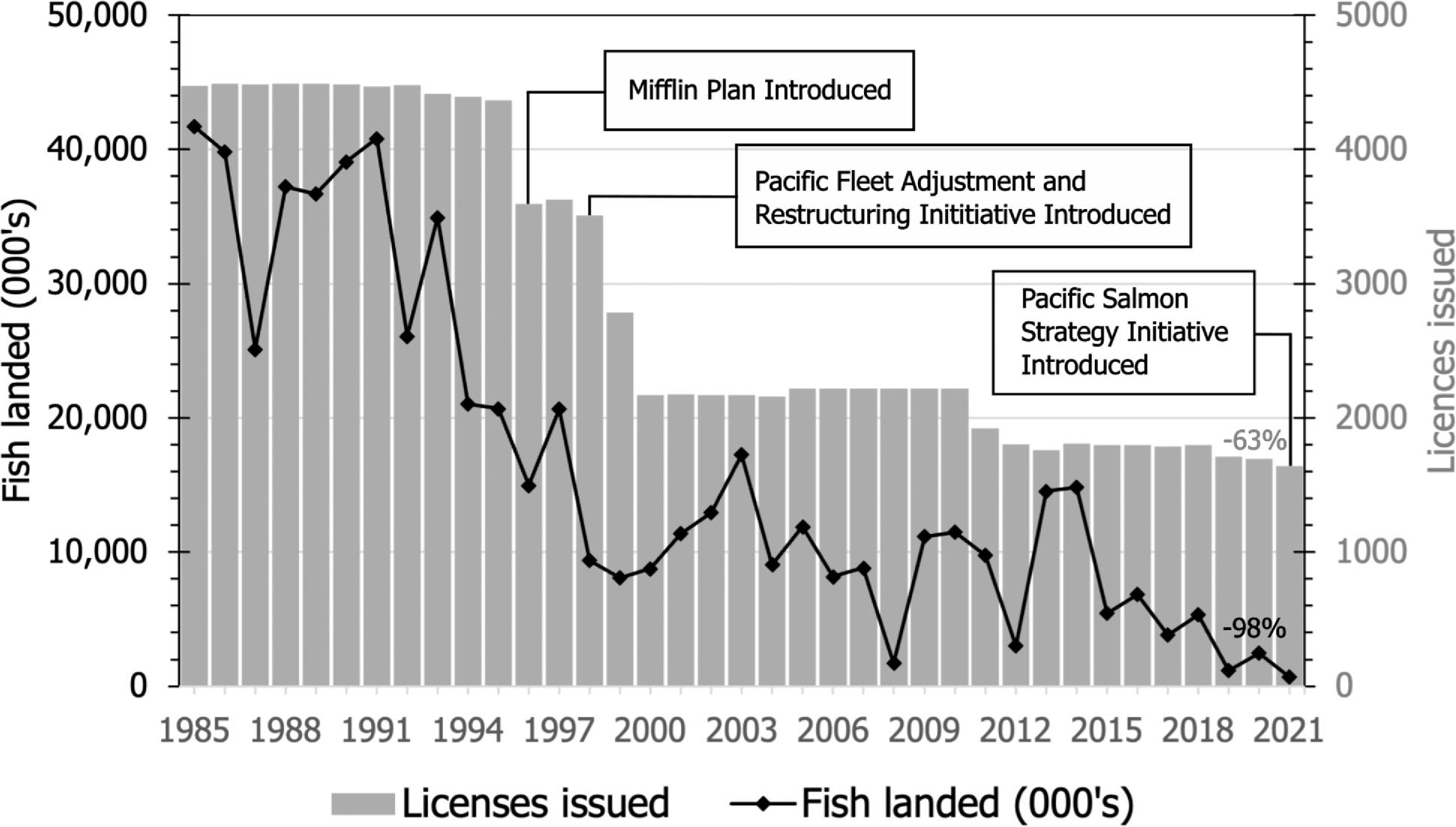

The decline of salmon has had profound implications for the flexibility and economic viability of commercial salmon fishers in BC. In response to salmon population declines, Fisheries, and Oceans Canada (DFO, the primary Canadian fisheries management agency) shifted to a precautionary management approach in the mid-1990s with the goal of reducing commercial fishing pressure (

Nelson and Turris 2004). DFO instated the Mifflin Plan and the Pacific Fleet Adjustment and Restructuring Initiative (PFAR) in 1996 and 1998 respectively, which collectively reduced the commercial fleet to half its size by 2001 through licence buy-backs (

Butler 2008). The Mifflin Plan also introduced the area/gear-based licensing model used today that requires fishers to purchase different licences for each gear type (gillnet, troll, or seine) and area that they intend to fish. Over the last three decades, continual reductions in exploitation rate have been achieved through shorter and fewer fishery openings (sometimes as short as 6 h), and gear-based limitations on retention of vulnerable species (

Walters et al. 2019). Importantly, while the fleet size has diminished, total allowable catch (TAC) declined disproportionately over the last decade. Total commercial salmon landings in the 5-year period between 2018 and 2022 were 74% lower than in the preceding 5 years. In 2021, only 691 850 fish were landed, marking a record low and a >98% reduction from the industry’s historical high in 1985 (

North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission 2023). Over this same period, the number of commercial salmon licences issued dropped by 63% (

DFO 2023a), demonstrating that the small number of remaining salmon fishers are competing for an even smaller number of fish (

Fig. 1).

For an already stressed industry, recent changes may pose further challenges, making this a key opportunity to examine SR. The 2021 Pacific Salmon Strategy Initiative (PSSI) aims to curb salmon declines with a more precautionary management approach that includes further fisheries closures and another licence buy-back initiative. Moreover, the 2021 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (UNDRIP Act), along with DFO’s updated 2019 Fisheries Act, and 2019 Reconciliation Strategy, collectively commit Canada to facilitating better Indigenous commercial fishery access. This may have continuing implications for the allocation of salmon between and within various sectors, including the commercial fishery. Lastly, with climate change becoming a significant stressor on salmonid survival both in stream and at sea (

Mantua et al. 2010;

Abdul-Aziz et al. 2011;

Crozier et al. 2021), the future of salmon and the commercial fishery is arguably more uncertain than ever.

Discussion

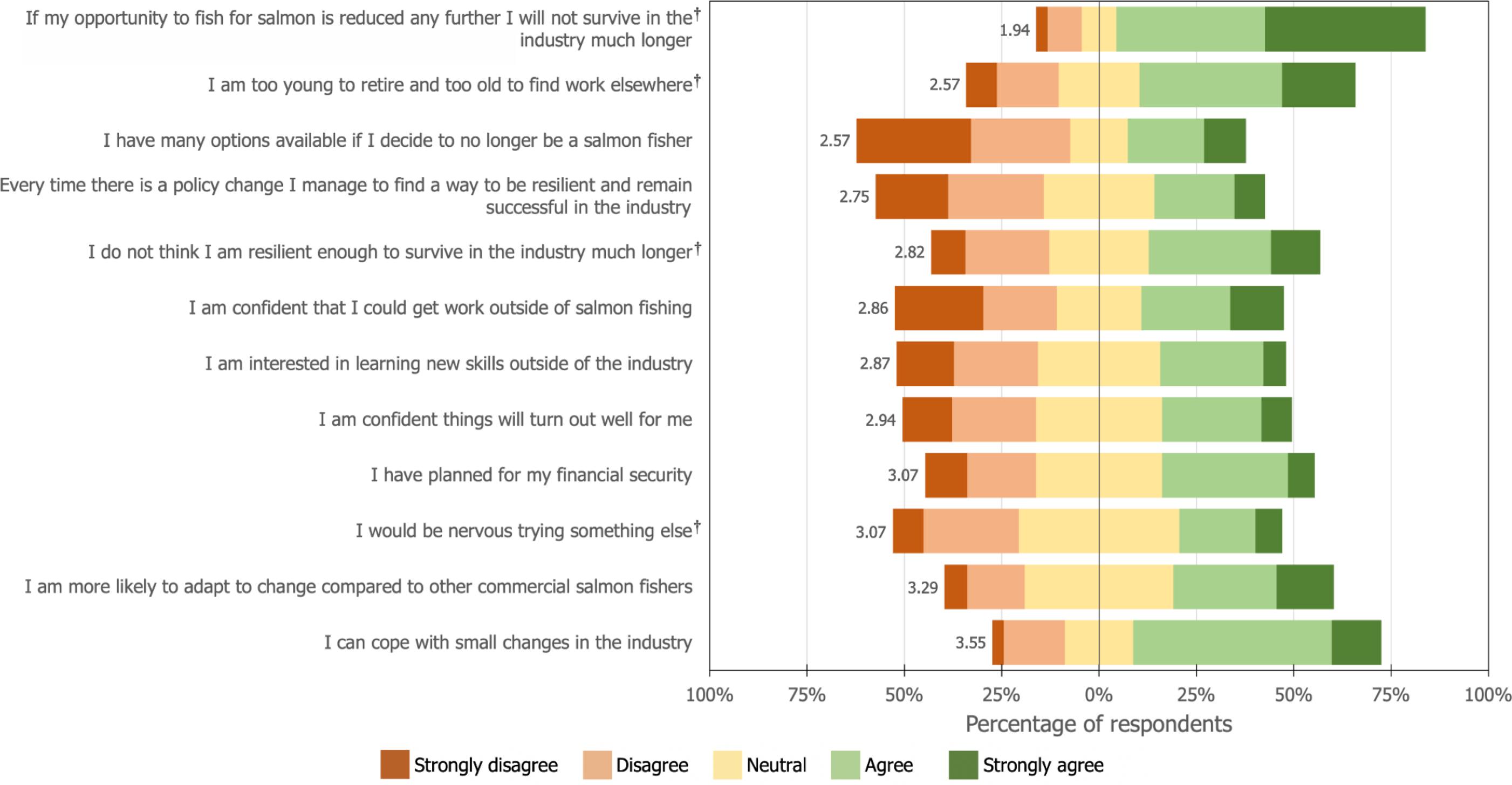

We found SR in BC’s salmon fishery to be low. The average SR score of 2.86 corresponds to negative leaning SR (<3.00). This score was largely driven by many fishers expressing their concern for both their ability to remain viable if there are further reductions in access to salmon, and their ability to find work outside of the industry. As compared to other fisheries that have been assessed with the same tool, 2.86 is low. For example,

Sutton and Tobin (2012) found a mean SR score among Australian commercial and charter fishers of 2.99. Other fisheries assessed with this tool have demonstrated positive leaning SR (e.g., average scores above neutral;

Marshall and Marshall 2007;

Marshall et al. 2009). The low SR scores reported here are contextualised by the extensive nature of our respondents’ perceived barriers to their adaptation.

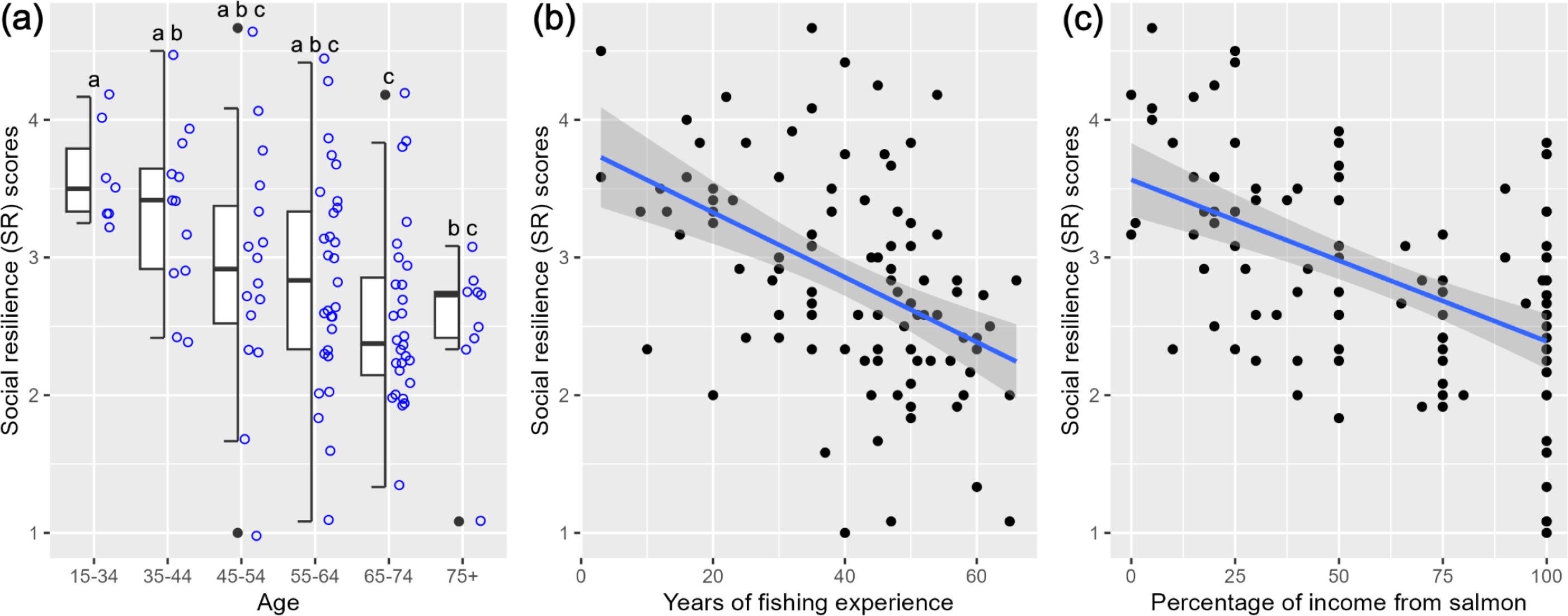

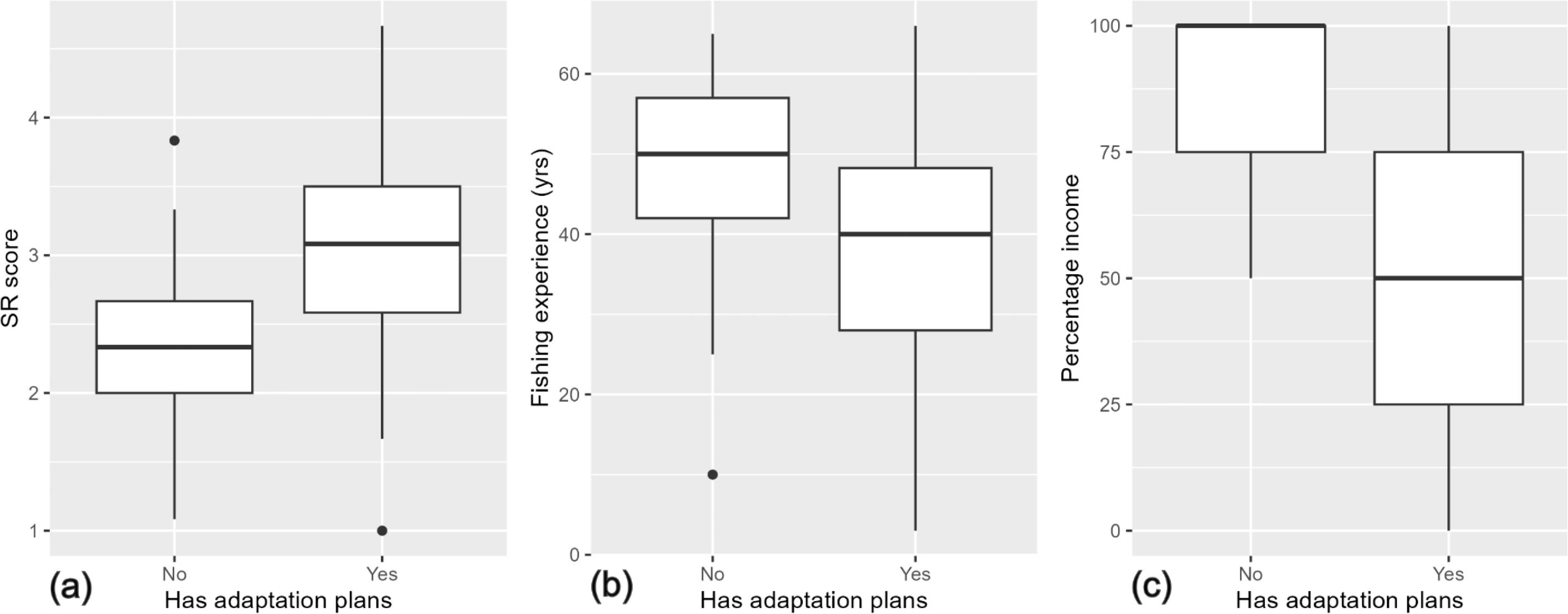

We found that socioeconomic characteristics—specifically age, years of fishing experience, and percentage of income earned from salmon—were correlated with salmon fishers’ levels of SR. Fishers who were younger, less experienced, and earning less income from salmon were generally more socially resilient. These same socioeconomic predictors of SR were also identified in Australian commercial fisheries (

Sutton and Tobin 2012). Our finding that fishers with a lower reliance on salmon were more resilient is expected given that diversification can reduce economic risks associated with resource dependency (

Finkbeiner 2015;

Matsuzaki et al. 2019) and enable greater flexibility (

Silva and Lopes 2015). However, considering that our study did not find a relationship between fishers’ SR scores and their number of licences or gear types used, our results suggest that diversification within the salmon fishery alone is not a desirable strategy to increase SR. This is not surprising considering that salmon fishery openings across licence areas often coincide (

Butler 2008). The lower SR of older and more experienced fishers may in part be explained by the tendency for this demographic to have more occupational attachment (

Marshall and Marshall 2007), and greater resistance to learning new skills (

Silva et al. 2020). However conversely, other research has shown that older and more experienced fishers can also be less socioeconomically vulnerable (

Villasante et al. 2022), and more resilient due to greater accumulated knowledge (

Teh et al. 2012).

Our results illustrate the role that structural factors related to licencing have in inhibiting individuals’ SR in Canadian Pacific fisheries more broadly. Many fishers described their ability to diversify as constrained by policies that have driven increased costs for many Pacific commercial fishing licences and quota, and moved fisheries access and income out of local communities. Demand and speculation from investors have been enabled by the privatisation and rights transferability (e.g., transferable quotas) of Pacific fishery resources, and the lack of an owner-operator policy. As a result, licences have concentrated under corporate, foreign, and investor control, and the prospect of licence ownership has slipped out of the reach of many young fishers and those from rural and Indigenous communities (

Haas et al. 2016;

Silver and Stoll 2019;

Bennett et al. 2021;

Silver and Stoll 2022). This problem is not unique to Canada (see

McClenachan and Neal 2023) and results from global efforts to address the ecological devastation caused by overcapitalised and open access industrial fisheries (

Wingard 2000). Without licence ownership, many fishers resort to signing quota lease agreements with licence owners such as fish processors, or so called “armchair fishermen”, who lease their quota as passive income. Lease prices are often high to the point that lessee operators may struggle to cover basic operating costs, crew shares, and to reinvest in their vessels to improve safety and performance (

Edwards and Pinkerton 2020). As highlighted by our respondents, DFO’s policy to marry stacked vessel-based licences only further exacerbates licence affordability and de-localisation issues, as licence packages are often only affordable to corporate buyers. These challenges signal that bolstering SR will require a major policy overhaul. UFAWU-Unifor has been particularly vocal in this regard, advocating for the need to prevent investor and corporate ownership of licences through developing owner-operator policies, and incentivising new entrants with low interest loans (

UFAWU-Unifor 2021). Other scholars have recommended considering claims of resource adjacency in allocating access rights (

Bennett et al. 2018).

While our study indicates that salmon fishers exhibit low SR on average, a glimmer of optimism emerges as a substantial cohort of less experienced individuals within the industry demonstrates a proactive stance towards adaptation—despite their perceived adaptation barriers. We found that 73% of fishers reported having plans to adapt if there are further declines in access. On average, these individuals had significantly higher SR scores than those without adaptation plans, highlighting a strong linkage between perceptions of personal risk and SR. These individuals were realistic about the risks associated with the industry, many of whom reported having “already diversified”, as corroborated by their smaller average proportion of personal incomes earned from salmon. These fishers were united by the recognition that “the good old days just don't exist anymore”, and that irrespective of distaste for current management, the only way to persist in the industry's uncertain future is to be flexible and prepared for change.

We demonstrate that fishers’ trust in DFO is very low, and positively correlated with their SR. Distrust in management is a commonality in fisheries. For example, among Maine lobstermen, 62% reported not trusting managers (

McClenachan et al. 2020), with decreasing trust in federal as compared to regional fisheries management institutions (

McClenachan and Neal 2023). Likewise, 48%–62% of small-scale Brazilian fishers reported having no trust in various institutional actors involved in fisheries management (

Silva et al. 2021). However, the trust in fisheries management reported here is low in comparison to these aforementioned studies, with 66% and 75% of salmon fishers reporting having no trust in DFO’s ability to conserve salmon and help fishers adapt, respectively. Trust is often regarded as important in driving SR (

Stern and Coleman 2015;

Mortreux and Barnett 2017), and prior research has demonstrated that fishers’ trust in management can be a predictor of both initial and persistent psychological trauma following fishery collapse (

Scyphers et al. 2019). Trust and SR are particularly important in the context of Canada’s commitment to ecosystem-based fishery management (EBFM), which requires management institutions to effectively draw on diverse knowledge, abilities, and viewpoints to achieve sustainability targets (

Glenn et al. 2012;

Stephenson 2012;

Stern and Baird 2015).

Taken together, our results suggest that fishers are experiencing a major loss of “systems-based trust”, that is, trust in the rules, procedures, and policies that define salmon management and Canadian fishery and resource management more broadly (

Stern and Baird 2015). In particular, fishers demonstrated a diminished faith in the equity of management systems across two scales. First, within commercial fisheries, tensions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous fishers were small in comparison with the consensus that the concentration of licence ownership in the hands of corporations/processors is inequitable. This well-documented problem in Canadian Pacific fisheries (

Haas et al. 2016;

Silver and Stoll 2019;

Bennett et al. 2021;

Silver and Stoll 2022) may be driven by a lack of knowledge of, and agreement over social performance indicators in fisheries (

Stephenson et al. 2019), or a conflation of social with economic performance indicators (

Brooks et al. 2015). Second, we found that a key component of low trust is related to perceived inequities in the Federal government’s natural resource decision-making, which has reduced access to commercial salmon fisheries, yet has failed to work with the BC government to address the legacy of industrial logging in riparian salmon habitat, and continued to allow foreign-owned Atlantic salmon aquaculture in BC waters despite established negative effects on wild salmon (

Bass et al. 2022;

Bateman et al. 2022)—a decision heavily critiqued by the scientific community (

Godwin et al. 2023). Fishers perceive that the narrow focus on reducing commercial exploitation rates—without simultaneously taking extensive measures to reduce the massive impacts from destructive industries whose benefits are concentrated in corporate owners outside the province—is a failure to prioritise conservation, and instead yielding to powerful industry lobbyists.

Our results must be viewed within the context of Canada’s ongoing efforts to reconcile with Indigenous peoples after centuries of dispossession and marginalisation (

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015). The imposition of colonial policies and fishing practices in Indigenous territories acted to—and continue to act to—erode northwest coast Indigenous peoples’ long-standing connection to their marine resources, including salmon (

Atlas et al. 2021;

Steel et al. 2021). Mounting local and international pressures (e.g., UNDRIP), and—most importantly—the assertion of aboriginal rights by Indigenous communities in court have resulted in a legal and policy landscape that is gradually shifting to better enable Indigenous fishers to access their territories’ marine resources (

Bennett et al. 2018). Yet Indigenous ownership of commercial salmon licences has decreased disproportionately to other user groups over the last three decades (

Butler 2008;

DFO 2015). Many Indigenous fishers have now become reliant upon DFO’s Pacific Integrated Commercial Fisheries Initiative (PICFI program) to access commercial fisheries, including salmon. The PICFI program requires Indigenous communities seeking fishery access to create and manage “corporate style” Commercial Fishing Enterprises (CFEs) which are annually designated DFO-owned commercial fishing licences (accrued through the successive commercial sector licence buy-backs). Fishers can then sign lease agreements with CFE’s to obtain commercial fishing access in the form of temporary licences or quota. While PICFI aims to support Indigenous engagement in commercial fisheries, the PICFI CFE structure can lead to challenges for fishers. First, Indigenous fishers can face uncertain long-term access since licences are designated to CFE’s annually. Second, CFE’s are not united by a standard management structure or policy requirements for leasing, meaning that Indigenous fishers may not have guaranteed priority over other quota/licence applicants (non-Indigenous fishers or corporations) or access to affordable lease rates. Indigenous fishers rely on profitable engagement in commercial fisheries to maintain vessels required in the FSC fishery and support their communities’ food security (

Burke 2010). Clearly, more work is needed to ensure that Indigenous fishers can participate and thrive in commercial salmon fisheries. Moving away from “corporate style” lease-based licence systems and towards the transfer of commercial quota/licence ownership and control to Indigenous fishers may be an important next step in seeing this happen, and in recognising aboriginal rights, title, and autonomy. This is particularly salient because the majority of territory in BC was never ceded to the Canadian state in the first place. Given that some of our Indigenous survey and interview respondents expressed concerns surrounding food security and FSC fishery access, future research with Indigenous communities in BC should explore the relationship between commercial fishery access and food security/food sovereignty. This is particularly important for those communities that are most isolated and have historically suffered disproportionate losses of commercial fishery access.

Finally, there are important methodological limitations that should be recognised when interpreting our results, particularly for the survey. First, our statistical power is limited due to a low response rate and small sample size, particularly when comparing SR scores between sub-samples. Second, our low SR scores and overall pessimistic results could be attributed to a survey bias, with those eager to express their concerns most likely to complete the survey (non-response bias;

Fisher 1996). However, this dominant pessimistic narrative is supported by other research in Canadian Pacific fisheries (

Bennett et al. 2021;

Harper et al. 2023) and our optimistic respondents describing themselves as “few and far between”. We also aimed to reduce the likelihood of non-response bias by taking steps to increase response rate and sample size (

Krenzke et al. 2006;

Mason et al. 2020). This included providing (1) the opportunity to remain anonymous, (2) a short length (<15 min) that did not require the completion of written sections to be submitted, (3) a user-friendly online format, (4) regular reminders to complete the survey, and (5) an entry into a $200 prize draw. Lastly, there are limitations with relying solely on individuals’ perceptions to measure their SR (

Sutton and Tobin 2012). Perceptions are subjective beliefs rather than objective measures, and as such our measures of social resilience should only be considered as measures of perceived SR. Developing objective measures of SR should be a key consideration moving forward.