Poor mental health negatively impacts farmers personally, interpersonally, cognitively, and professionally

Abstract

Farmers globally face significant occupational stressors and are reported to experience high levels of depression, anxiety, burnout, suicide ideation, and suicide. While the impacts of high stress and poor mental health have been well-studied in the general population, and to some extent, in specific occupations, the impacts on farmers are understudied. The objective here was to explore the lived experience of high stress and (or) poor mental health in Canadian farmers, including the perceived impacts. Using a phenomenological approach within a constructivist paradigm, we conducted 75 one-on-one research interviews with farmers and people who work closely with farmers, in Ontario, Canada, between July 2017 and May 2018. We analysed the data via thematic analyses and identified four major themes. Participants described myriad negative impacts of farmers’ high stress and (or) poor mental health: (1) personally, (2) interpersonally, and (3) cognitively, which ultimately negatively impacted them (4) professionally, including consequences for productivity, animals, and farm success. The data described far-reaching, interconnected impacts of high stress and poor mental health on participants, the people and animals in their lives, and most aspects of their farming operations, financial viability, and success. Farmer stress, mental health, and well-being are important considerations in promoting sustainable, successful agriculture.

1. Introduction

Stress is one of the most researched topics within the field of farmer mental health (Díaz Llobet et al. 2024). The myriad stressors that farmers face are globally well known and reported to include long work hours, time pressures, finances, equipment breakdown, unpredictable and changing weather, social isolation, geographical isolation, market fluctuations, agricultural legislation, working with family, and fears or uncertainties around farm succession (Booth and Lloyd 2000; Gregoire 2002; Firth et al. 2007; Kearney et al. 2014; Truchot and Andela 2018; Yazd et al. 2019; Brennan et al. 2022). Research with farmers in Canada, Finland, and the United Kingdom has reported farmers to experience high levels of stress (Walker and Walker 1988; Booth and Lloyd 2000; Fraser et al. 2005; Kallioniemi et al. 2016; Jones-Bitton et al. 2020; Thompson et al. 2022).

Many stressors experienced by farmers are outside of their control, which can especially lead to feelings of helplessness and hopelessness and the development of poor mental health outcomes (Marin et al. 2011). Indeed, farmers worldwide are reported to have elevated risk of anxiety (Sanne et al. 2004; Jones-Bitton et al. 2020; Thompson et al. 2022), depression (Elliott et al. 1995; Sanne et al. 2004; Torske et al. 2016; Jones-Bitton et al. 2020; Thompson et al. 2022), psychological distress/morbidity (Brumby et al. 2012; Hounsome et al. 2012; Jones-Bitton et al. 2020), and burnout (Jones-Bitton et al. 2019; Reissig et al. 2019; Thompson et al. 2022). A 2019 systematic review of 28 articles compared farmers’ mental health with other occupational groups; 20 studies (71%) suggested farmers have “worse mental health issues than the general population” (Yazd et al. 2019). While much has been reported on farmers’ stressors and stress, and to a relatively lesser extent, the poor mental health of farmers; limited research focuses on the impacts of high stress and poor mental health on farmers, their farms, and the communities in which they live and work.

In the general population, the impacts of stress are well-documented. Briefly, stress affects all systems of the body including the musculoskeletal (e.g., tension headaches/migraine, low back pain, chronic pain); respiratory (e.g., exacerbation of pre-existing respiratory diseases like asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease); cardiovascular (e.g., increased risk for high blood pressure, heart attack, stroke); endocrine (increasing the risk of outcomes like diabetes, obesity, and immune disorders); gastrointestinal (e.g., changes to gut microbiome, indigestion, discomfort, exacerbation of inflammatory bowel syndrome and irritable bowel syndrome); and reproductive system (e.g., decreased libido and sexual desire, erectile dysfunction, reproduction, and exacerbation of premenstrual syndrome and symptoms of menopause) (Richardson et al. 2012; American Psychological Association 2018). Stress is also reported to be positively associated with higher cancer incidence among initially healthy people, and with poorer survival in patients with diagnosed cancer, although the potential effect of publication bias on these reported associations with should be considered (Chida et al. 2008).

Similarly, mental illnesses are reportedly associated with other serious health outcomes. Depression and anxiety are positively associated with myriad chronic health conditions including heart disease, obesity, diabetes, asthma, hypertension, ulcer, arthritis, back/neck problems, and chronic headache; the risks are significantly higher with the comorbid experience of both depression and anxiety (Scott et al. 2007; Rotella and Mannucci 2013; Bobo et al. 2022). Depression may also be associated with accelerated aging via shorter telomere length (Verhoeven et al. 2014). Anxiety disorders have been positively associated with increased risk of mortality by natural and unnatural causes, and comorbid depression–anxiety as associated with increased mortality from unnatural causes (e.g., accidents, suicide) (Meier et al. 2016). Indeed, death by suicide has a strong relationship with mental disorders, particularly depression (Favril et al. 2022).

Primary studies of the impacts of high stress among farmers are far fewer in number and breadth than with the general population, although it seems unlikely that farmers would be differently affected physiologically. Extant literature reports that high stress in farmers is associated with depressive symptoms (e.g., feeling down/sad, loss of motivation, suicide ideation, withdrawing, negative self-talk, low self-esteem); neurotic symptoms (e.g., worrying, constant thoughts about work, nervousness); affective symptoms (e.g., frustration, disappointment, irritability); and physical symptoms (e.g., physical illness, tiredness, back problems, headaches) (Walker et al. 1986; Raine 1999; Parry et al. 2005; Staniford et al. 2009; Olowogbon et al. 2019). In an Australian qualitative study, rural financial counsellors described recognizing physical (pale skin, body language) and cognitive (confusion, impaired decision-making) signs of farmer distress (Gunn and Hughes-Barton 2022). Several studies have also reported that stress and depression are positively associated with on-farm injuries (Lowe et al. 1996; Simpson et al. 2004; Jadhav et al. 2015). While these studies are helpful, several used stress symptom checklists, which provide only superficial understanding of the issues. Indeed, a recent bibliometric review of global farmer mental health research identified that most research in this field involves quantitative surveys, and highlighted a need for further qualitative research (Díaz Llobet et al. 2024). Where some qualitative studies provided more nuanced understanding, many were smaller in size and limited in geographical scope. Given differences in farming and farming systems from country to country (not to mention within countries), there exists a large gap in knowledge surrounding farmer-specific impacts of stress and poor mental health.

An in-depth understanding of the lived experience of high stress and poor mental health, including the perceived ways in which they impact farmers and various aspects of their lives and livelihoods, may help bridge divides between farmers and the larger societies of which they are part. For example, this understanding could help agricultural communities, governments, health care practitioners, and consumers better relate to, support, and resource farmers in their services to society. In doing so, this could also help make farming more viable and sustainable.

Hence, the objective of this study was to explore Canadian farmers’ perceptions and lived experiences of the impacts of high stress and (or) poor mental health on themselves, their lives, and livelihoods. Canadian farmers were chosen as the study population given the stark statistics around mental health in farmers in Canada (Jones-Bitton et al. 2019, 2020; Thompson et al. 2022), as well as the notable size, scope, and diversity of Canadian agriculture (Agriculture and AgriFood Canada, Government of Canada 2023).

2. Materials and methods

We used a phenomenological approach within a constructivist paradigm (Guba and Lincoln 1994) in this research. The authors recognize that their positions influence the research process, and hence, openly share their positionalities. All authors are Caucasian, cis-women, and feminists. AQJ is a veterinarian, epidemiologist, and former Director of Well-Being Programming in a large veterinary college in Canada. She was in her mid-40s at the time of writing and is a mother. She has enjoyed working with farmers for over a decade, and holds appreciation and respect for Canadian agriculture. This positionality may have influenced her interpretation of the data, specifically through a desire of wanting to help farmers in terms of their occupational stress and well-being. BNMH is an epidemiologist, researcher, mother, and passionate advocate for equitable access to mental health-services in agriculture. This positionality may have provided urgency to create opportunities for intervention, and as a woman, her feminist lens and gendered experience of mental health could contribute to her interpretation of the data. AS, a researcher, artist, and knowledge mobilization specialist with a strong foundation in qualitative and collaborative research methodologies, contributed to this project despite lacking a direct background in agriculture. Over the past 8 years, AS has collaborated on various farming and food systems research endeavors. AS’s outsider perspective allowed for the introduction of diverse questions and perspectives into the research process. This positionality may have facilitated a broader exploration of the data, offering fresh insights and viewpoints. AS’s outsider perspective might have led to a tendency to generalize findings or overlook important variations and nuances within the data, and without firsthand experience or deep immersion in agricultural settings, she may have inadvertently overlooked unique challenges faced by specific subgroups of farmers, in turn limiting her ability to capture the full complexity of their experiences. Finally, RT is a graduate student and farmer, who grew up and still lives in an agricultural community. She currently farms broiler chickens with her father, and is the first daughter in seven generations to continue their family farm. This insider positionality may have influenced her contributions to the project through her familiarity with participants’ experiences and farming culture, via elaborating on participants’ experiences in analysis meetings by making connections to her own.

Our team’s existing agricultural mental health working group (AWG), consisting of farmers and people who work with farmers, was used to recruit participants for the study. The AWG consists of farmers, agricultural industry and government professionals, and veterinarians from major commodity groups in Ontario, who are involved in their respective commodity organizations and communities. The AWG shared the study information to their networks via email and social media, which was helpful to reach many farmers within Ontario. An a-priori decision to recruit 75 participants was made based on budget and resources available, manageability of data to analyse, heterogeneity of the sample, and scope of research questions (Green and Thorogood 2018; Low 2019). During data collection, the research team decided no further interviews were necessary as sufficient breadth of experiences from different viewpoints had been collected which would allow for meaningful interpretations of the data to be created (Green and Thorogood 2018; Braun and Clarke 2021). The first 75 people to respond to the invitations who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled. The inclusion criteria were: (1) identifying as a farmer or someone who regularly works with farmers in their everyday employment (e.g., veterinarians, people from agricultural government or industry); (2) able to converse in English; and (3) 18 years of age or older. Interviews were scheduled at a time convenient for the participant, at their place of preference. Most often, this was in participants’ homes, but occasionally was in a private meeting room at the University. The interviews took place between July 2017 and May 2018.

We used a semi-structured interview guide to facilitate discussion (Appendix A). The guide included questions on a wide range of topics, including questions related to stressors, the lived experience of mental health, and knowledge and use of mental health supports; only those questions and data related to the perceived impacts of stress and poor mental health are reported here. We audio-recorded all interviews and created verbatim transcripts. We checked against the audio-recordings for accuracy prior to analyses.

We used thematic analyses to allow for the inclusion of both the rich, detailed descriptions of participants’ experiences and our experiences with farmers and Canadian agriculture to address the research objectives. The analysis was guided by Braun and Clarke (Braun and Clarke 2006), using both inductive and deductive approaches (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane 2006) and semantic (i.e., data-driven) and latent coding. All transcripts were read to familiarize ourselves with them. Two authors (AQJ and BNMH) and an acknowledged research collaborator then independently open-coded a selection of five transcripts and then discussed codes and impressions of the data. One author (BNMH) produced a codebook from this initial analysis and discussion, which included a list of codes, their definitions, and example quotations. All transcripts were then independently coded by at least two of three authors (AQJ, BNMH, and AS) using the codebook. The same three authors discussed further modifications of the codebook (i.e., reviewing, refining, and (re)naming themes) during bi-weekly meetings as the remaining 70 interviews were coded. Coding was reviewed, final analytical decisions were made, and themes and their interconnections were interpreted with all four authors via consensus. Throughout the process, we kept a detailed audit trail (Thomas and Magilvy 2011) and used visual memos (Prosser 2011), to aid understandings and for data validation purposes. We also used member checking as another data validation technique, presenting our findings to the AWG for feedback at one of our day-long meetings. Verbatim quotations from the transcripts were used and are presented here to provide thick, rich description (Green and Thorogood 2018) of the study findings. In some instances, square brackets were used to add or replace wording for context or clarity, and ellipses were used to remove unnecessary text that may have clouded understanding. Quirkos© software (Quirkos, Edinburgh, UK) was used to help facilitate data management and coding.

The Research Ethics Board at the University of Guelph approved the study protocol (REB 17-02-035). All participants provided informed written consent and completed a short demographic survey prior to the interviews. Participants received a $100 Canadian honorarium for their participation.

3. Results

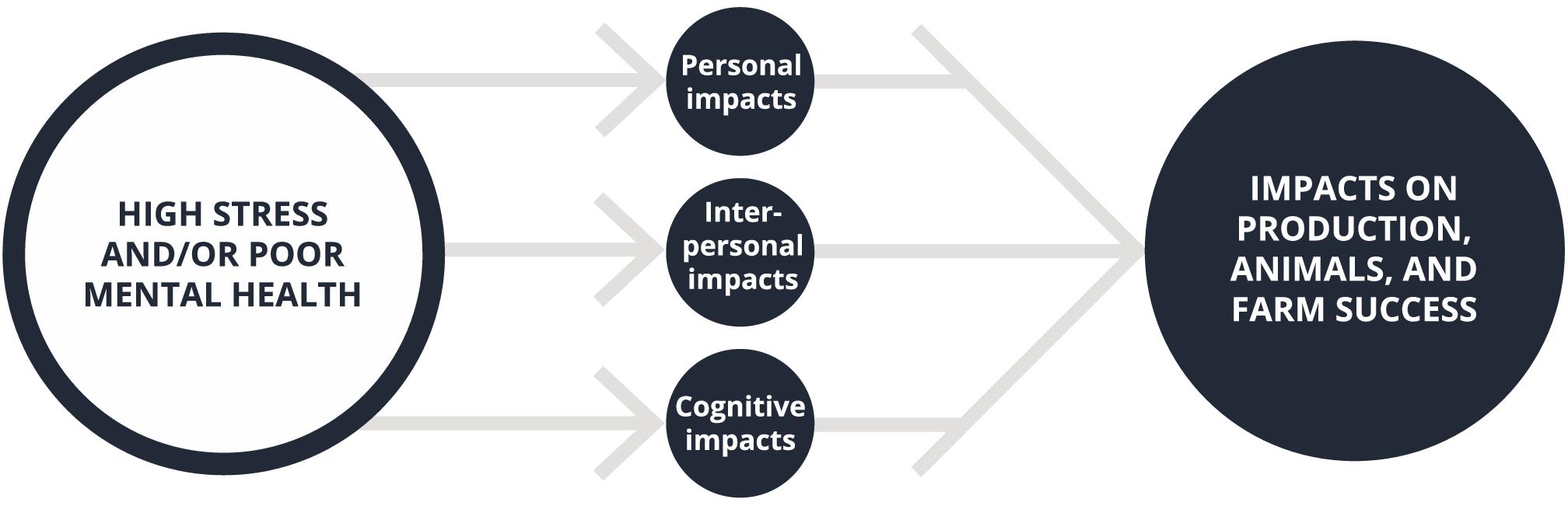

A total of 75 in-depth, one-on-one interviews were conducted between July 2017 and May 2018. Most interviews were conducted in-person (n = 65; 87%); 10 (13%) were conducted via telephone when the participant lived >200 km away. The length of interviews ranged from 45 to 75 min. The demographic survey was completed by 74 participants. Half of the participants identified as men, the other half as women, and their ages ranged from 25 to 78 years (average: 57). Self-reported employment included farmers (51/74; 69%); agricultural industry staff (14/74; 19%); food animal veterinarians (6/74; 8.1%); and one participant (1.4%) each from agricultural government, academia, and journalism. Although participants were enrolled first-come, first-served, the research team ensured diversity within the sample at enrolment. The sample included representation of farmers from all major Ontario commodities, including grain and oilseed, dairy, beef, poultry (chicken, eggs, turkey), swine, sheep, goats, vegetable, and fruit. Additionally, a variety of agricultural lifestyles common in Ontario agriculture were present in the sample, as farm owner/operators came from both large- and small-scale farms and used various practices (e.g., conventional, organic). Some participants worked off-farm jobs in addition to farming, while others’ sole occupation was farming. The research team decided the diversity of this sample was adequate to gain a thorough understanding of experiences relating to the research objective, and make meaningful interpretations from the data. Participants described a multitude of perceived impacts stemming from high stress and (or) poor mental health that had far-reaching consequences in their personal and professional lives. These impacts were summarized within major four sub-themes: (1) Personal Impacts; (2) Interpersonal Impacts; (3) Cognitive Impacts; and (4) Impacts on Productivity, Animals, and Farm Success, each having several associated sub-themes. A thematic map is shown in Figure 1. Each theme and sub-theme are described below.

Fig. 1.

3.1. Personal impacts

Participants described myriad ways in which they perceived high stress and (or) poor mental health negatively impacted farmers, including: (a) lost drive and motivation; (b) impacts to physical health; (c) avoidant coping behaviours; (d) self-isolation and withdrawal from others; and (e) suicide ideation and behaviours.

3.1.1. Lost drive and motivation

When facing chronic stress and depression, many participants described “loss of drive,” depletion of motivation, and a general “shutting down” that made “even simple tasks difficult”. They described difficulties getting out of bed, starting their farm chores, and addressing their long list of tasks related to the farm and business.

For example, one participant described what it felt like to lose their drive:

“I think the biggest thing that happens to you is you lose your drive, right? Like, you lose your initiative or whatever to get up in the morning and get that done. You kind of get more lethargic about your approaches to things.” {Participant (P)16}

And another noted some of the effects of this loss of drive and motivation:

“… you become complacent, just sit back and kind of quell up and don't do the stuff that you know you should do and that can take a bit of time until the business starts to suffer.”{P68}

3.1.2. Impacts to physical health

Multiple participants described high stress and poor mental health as having negative impacts to their physical health (“'Cause I know when you go through stress it starts to affect your whole body function, right? And there's a lot of things that start to change, right?” {P16}). High perceived stress was reported to trigger existing conditions like “migraines”, “psoriasis”, and “asthma”. Other participants described impacts to their cardiovascular and gastrointestinal systems. For example:

“I mean it's every year - just a couple Saturdays ago, I mean my heartbeat was at 175. I had a couple of my bigger growers who are having trouble, they were phoning that they were upset and I didn't know how to answer their problems and, I mean, I even went for a heart monitor test after 'cause my heart was racing ‘cause the stress was just overwhelming.” {P49}

“I would get very bad, like irritable bowel and I would have very bad problems with my back when I was really stressed. I was not handling it very well.” {P54}

Another participant described their chronic stress and anxiety as manifesting as unexplained aches and pains:

“I'd totally been worrying about and stressing about the farm and then my husband always will have aches and pains that are unexplained, and then, you know what? That's probably anxiety and we've just never really put it together…” {P36}

Some participants described decreases in appetite and weight loss (e.g., “I'm just trying to get through each day. I haven't been eating and in the last three weeks I've lost 13 pounds. Alls I want is to drink water. Nothing else appeals to me.” {P14}), where others described “gaining a lot of weight”. As one participant shared of a farmer close to them:

“Now he's like 300-and-something pounds and at the end of a bad day all he wanted to do was kick his feet up in the air and eat as many things as he could put his hands on.” {P22}

Stress was reported to cause some participants to “overwork”, which subsequently had impacts on physical health: “You tend to work more hours in more mental stress and you can feel it, you're really tired and at the end of the day. It's not a happy tired.” {P25}

Sleep was commonly reported as being negatively impacted by high stress, both in terms of quality (“it can affect your sleep” {P14}) and quantity (“because when people are under stress they don't sleep enough” {P2}). This poor sleep was described as especially troubling because “if you don't sleep enough then your physical health starts to go as well” {P2} and poor sleep “affects the way I go about my work, it affects my decision making, and it affects how I interact with people.”{P29}

Indeed, several participants described on-farm accidents and injuries as consequences of poor sleep. For example:

“…when you get up the next day you're supposed to be fresh and you're not. And maybe you're working with machinery or PTOs [power takeoffs] or something, and for a split second you lapse and you do something you shouldn't and there's a – so your mental health winds up causing you physical disability because you get hurt or whatever and then you've done an unsafe operation which you know you shouldn't do but you did anyway.” {P10}

“… would you consider stress leading to lack of sleep, leading to a farm accident sort of a causation of poor mental health? Because we did have one of those happen on the farm once upon a time and it was the most horrendous thing I've ever seen. It was a guy got his arm sucked into one of our pieces of machinery. He ended up with I think 153 stitches in his arm. … a lack of sleep and an anxiety about getting your crop off, and one moment of just not thinking about what you should be thinking about and [SNAP] there goes your arm.” {P22}

“Maybe they take risks or they're working 22 hours a day. Well there's gonna be an accident, right? I mean, how many guys probably got hurt because they just were working too hard and you can't afford to take time off?” {P10}

3.1.3. Avoidant coping behaviours

Participants commonly described avoidant coping behaviors resulting from chronic stress and poor mental health, in that “Stress causes secondary things. Lack of sleep, drinking more caffeine, self-medicating with alcohol and those kinds of things.”{P25}

Participants described increased substance use as a consequence of high stress. For example, when asked how he dealt with stress, one farmer answered: “Caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine. That doesn't really sound good, but that's reality.” {P15} Another shared, “Specifically in the fall when those crops need to come in—huge rate of smoking I think is due to that anxiety… I start chain smoking more and more.” {P72} Other participants described use of cannabis (“I'm a pot smoker. That's how I deal with my anxiety and my things in my box that I never want to open really and look at.”{P22}). Numerous ramifications of substance use as a coping strategies were shared (e.g., “So then it leads to alcoholism, it leads to domestic violence. It leads to all sorts of other ways of expressing itself that aren't healthy and yeah, they can become very, very destructive” {P20}).

In addition to substance use, excessive spending was also reported, although to a much lesser extent:

“Like I had an obsession with tools and if I was having a bad day I'd go and select a tool that I didn't have and bring it home and it was great. I'd justify buying that tool. It wasn't something I needed, but I justified buying it and I got the warm and fuzzies for doing that.”{P39}

Another participant described “needing screen time to leave this world” which became a “vice with my marriage … Instead of drinking and drugs or whatever, it was screen time, so I would ignore her. Whenever I got stressed out from the barn, I couldn't make it to lunch without needing screen time to leave this world… I just needed to leave.”{P35}

This feeling of needing “to leave” was a commonly described experience by many participants, resulting in self-isolation and withdrawal from others.

3.1.4. Self-isolation and withdrawal from others

In dealing with chronic stress or poor mental health, participants described intentionally trying to “shut down emotionally” and “not feel too much” as a way to cope. Several described “pulling away” from people and events that they normally enjoyed. For example, one participant shared, “I've found myself, I would just withdraw and wouldn't be honest with my wife about what's going on…” {P25} and another explained “…just wanting to just shut out the world and just block it out and not participate in humanity.”{P20}

Some participants described this self-isolation as stemming from perceived judgement or comparison with others, and “not wanting to admit that there's a problem to anybody” {P25}. As one participant explained:

“When things were bad I didn't even want to see another farmer 'cause the last thing I wanted to do was talk about all the crap that was going on with our farm and I didn't want to hear about how great everything was going at theirs because, you know, it just pissed me off. So yeah, you just kind of – I just wanted to stay at home and not really see anybody.”{P44}

While most participants described social withdrawal as a negative experience or unhelpful coping mechanism, some farmers discussed distancing themselves from others as an active and healthy way they coped with stress (e.g., “I just had to go find a place and be by myself” {P76} and “I go count the cattle, go for a walk in the hills. That does a lot of good actually.”{P30})

3.1.5. Suicide ideation and behaviours

Another impact of chronic stress and (or) poor mental health described by participants was suicide ideation, which was discussed directly (e.g., “You just get more depressed, more suicidal thoughts. You just want to walk away from it all. You wonder if you did something in life to deserve this or you're just not happy” {P19}) and indirectly (“Oh, because I'm stressed and some days I wish I wasn't here.” {P26})

While it is not a focus of this paper, death by suicide among farmers was regrettably commonly reported by participants as stemming from chronic stress. As a participant working in the agricultural industry said, “Yeah, we've had two or three farmers that kind of did away with themselves 'cause they just couldn't handle the stress level.” {P23} Another shared:

“We're a long way from the point where farmers find it easier to – and this is the unfortunate part – easier to pick up and talk to someone, and seek the tools they need to address their issues mental health-wise, than it is for some of them at least to pick up a gun or a rope.”{P18}

3.2. Interpersonal impacts

Participants commonly described how stress and (or) poor mental health negatively affected their relationships with their spouse/partner, family, co-workers, and other community members via “tensions”, “irritability”, anger, “outbursts”, arguments, blame, and poor communication. As one participant explained, they perceived their stress as negatively impacting how they dealt with everyone around them:

“When things aren't going well, then my family feel like they're walking on eggshells, that I am unstable and could explode at any moment for any unimaginable reason. Same thing with friends, neighbours, people that I'm close to, people that I'm not close to. Doesn't matter. If things aren't going well then I become very angry, very defensive, very combative…” {P20}

Many participants discussed how high stress was perceived to impact their interactions with their spouse/partner (e.g., “we bicker, and we argue, and we have a short fuse” {P54}), which compounded already stressful situations. By way of example, one participant shared, “My husband and I were arguing a lot about different things just “cause we're both stressed out” {P1}, and another said, “Like, it's hard. It's very hard on your marriage. Even if you have a strong marriage. {T4}” In several instances, farm stress was described as contributing to “erosions of marriage and the family unit” and leading to divorce (e.g., “Well sometimes when farm couples divorce it's because of mental stress in one person or the other and you can see it.”{P26}).

The tightly knitted way in which family members work together on farms was often discussed negatively in that one person’s stress impacted others’ (e.g., “it's not just the farmer themselves that goes through the stress—it is their whole family” {P2}), leading to tensions within the family. As two participants explained, “I'm just so angry at everybody. Which is really awful but I know it's there—and yeah, even my poor husband is like, “you're not very nice to me in the barn”…” {P37} and “Our family unit is rocked and our family unit has been very solid. I think it's definitely being rocked because of the great amount of stress we're under.”{P14}

The impact of these stress-induced interpersonal dynamics on children were also discussed. For example:

“The kids, our children pick up on it, you can tell. They are definitely less well behaved and I think they're stressed, especially our middle child. You can tell he takes a lot upon himself and he gets stressed.”{P54}

While participants more commonly described how their stress negatively impacted their dealings with family members, and that this was compounded by the fact that they work and live together, a smaller number of participants discussed how being a family and working through the issues together was helpful (e.g., “I think just everybody working together I guess and us all just doing it all together. I think that helps. Yeah, that's it really. I think just doing it as a team and working well together…” {P60}).

Finally, in rare instances, participants described an inability to cope with stress and mental health challenges as having high potential to culminate in violence toward humans or animals. Many participants expressed feelings of concern among themselves and their family members:

“I snapped. And I erupted and people have never seen me do that. So it kind of concerned them that holy shit, this guy was – I was ready to tear out someone's throat and they're like “oh, he's not in a good spot”, you know?” {P69}

“I know of an individual too recently I was out helping and he was cursing, and swearing and just flying off the handle, those kind of things. … They were under a lot of stress and that's affecting them and so … and it's like, what if it gets worse? What if it escalates, where does it go next, right?”{P16}

“…and the end result is there's spousal abuse, or domestic violence, or violence against animals. They let their emotions out through different avenues, right?” {P10}

3.3. Cognitive impacts

Participants described numerous cognitive impacts associated with their stress and (or) poor mental health that, in turn, had impacts on their farming and businesses. These cognitive impacts were captured within three sub-themes: (a) difficulty making decisions and making poor decisions; (b) difficulty problem solving; and (c) avoidance and procrastination of responsibilities.

3.3.1. Difficulty making decisions and (or) making poor decisions

Decision-making was described as a major source of stress among participants. Many lamented about the sheer number of decisions they needed to make regularly, the large amount of money riding on those decisions, the length of time the results of those decisions will be relevant, and the lack of control around what ultimately impacts their actions. The effects of stress and poor mental health were described to significantly compound the difficulties in making decisions (e.g., “Your brain can't think right, can't make good decisions” {P68}) and as leading to making poor decisions (e.g., “Yeah, I made some pretty crappy decisions at that point in time” {P15}), which often came with long-term ramifications (e.g., “…you make a bad decision in your selection of a bull or whatever—that could affect you for two, three years down the road, right?” {P49}). As one farm business advisor shared,

“…depending on how much they're feeling stressed – they just mentally can't focus, can't be productive because they just feel like they're drowning and then that just again compounds the problem because then they're not being productive, or getting stuff done which then means the next day they just feel worse about even more.” {P70}

Other participants explained, “I make some questionable decisions. I make decisions that I look back on and that was really stupid. And I think it's because at the time you're not really thinking. You're just trying to get through it” {P15} and, “I probably don't make the best decisions, or don't seek out advice from others where they could probably help me if I asked them.” {P29}

Another participant recalled working with a farmer who was experiencing poor mental health and being concerned they would make an irrational decision with high financial implication:

“One thing being that they could not make a rational decision. … He was looking at a big combine and stuff that they couldn't afford. I said [to the spouse] “you go to the dealer and tell them that they are not to make any deals with him without your, you know, permission, without you co-signing.” Nothing was to be sold to them because they're not making rational decisions, and the dealer doesn't know that they're not making rational decisions. They look at it as “oh, we've sold a combine”. It doesn't matter that they can't pay for it.” {P53}

3.3.2. Difficulty problem solving

The perceived cognitive impacts of high stress also included limiting participants’ abilities to effectively problem solve, with “the stress level [being] very, very high [too much to] try and come up with solutions” {P11}. Commonly, participants also described the stress as magnifying issues to the point of being unable to solve them. For example, one participant shared:

“The farmer hits the brick wall and he cannot get over the brick wall. It's all he sees. They don't see there's 12 other options… “Cause they're hitting their head against the brick wall. And the small things become really, really big and overwhelming and overpowering so that you can't break it down, so even when we take an issue or a job and break it down into smaller pieces. You can't see the smaller pieces, you just see the overlying, big job, the big stress, the big worry.” {P10}

And a participant described of her spouse:

“Everything was huge. Everything was so much bigger than it was, and even though you would sit down and make a list, and write things up for him, he couldn't see that little bit. He only saw, you know, “how are we gonna get the hay done? I can't do the hay, and I can't do this’ and it didn't matter how many times you said “it's okay, it's fine, we'll get it done’, they are not in the mind-set to accept that kind of rationale.” {P53}

3.3.3. Avoidance and procrastination of responsibilities

Participants described avoiding responsibilities in response to stress and poor mental health, like “push[ing] things aside” {P72} and “crawl[ing] into bed” {P32}, which stemmed from “an inability to face issues” {P72}, and led to them “getting behind” {P55} and the “business start[ing] to suffer” {P68}. For example, some participants withdrew to avoid work:

“I can't focus at work because I'm so stressed with something that's going on. I overthink everything and sometimes it'll get so bad that I'll just go home and I'll just crawl into bed and just go to sleep and just not want to deal with anything. I'll just go to bed and I just won't deal with anything.” {P32}

“I do all the books for the farm as well and I used to have it very organized and definitely I could've cared less [when I was mentally ill]. I just paid whatever bills we could pay and threw the rest in a box and I was very unorganized as far as that kind of stuff goes. So that definitely was impacted and it was just because I didn't want to look at any more numbers. I knew we didn't have the money to pay for stuff and so I didn't even want to look at it…” {P44}

while others procrastinated:

“What I'm trying to say is you're under a lot of stress and it's bothering you. You say “well I'll just leave it for tomorrow”, you procrastinate a little more and next thing you know it starts to impact your business.” {P16}

The tendency for avoidance and procrastination often served to exacerbate the issues on the farm. As one farm advisor shared,

“This is a business and stuff needed to be dealt with in a time appropriate manner, and they weren't able to see that, and they weren't able to do it. So that exasperated that situation and that made that situation 10 times worse.” {P5}

Hence, the cognitive impacts of high stress and poor mental health were reported to have ramifications for farm success.

3.4. Impacts on productivity, animals, and farm success

Negative impacts on productivity, animals, and overall farm success as a result of the personal, interpersonal, and cognitive impacts of high stress and (or) poor mental health were frequently discussed by participants. These impacts were demonstrated across four sub-themes: (a) decreased personal productivity; (b) decreased animal welfare and (or) animal productivity; (c) financial consequences; and (d) scaling back of farm business or ending farm operations.

3.4.1. Decreased personal productivity

The decreased drive and cognitive impacts associated with chronic high stress and (or) poor mental health were described as reducing participants’ personal productivity (and the ability to operate the farm (“You're definitely not as productive or as efficient, or doing as good a job”… Like, everything will suffer” {P55}). For example, one farmer shared:

“I find that when there's that day-to-day stress going on… I just become far less productive in general. So yeah, it would impact, like it impacts my capacity to do my job probably more than anything and then you just kind of start to feel like you're not doing any of it very well.” {P43}

Another farmer elaborated on the connections between mental health, productivity, and success:

“The farm looks not great, his cows – he has a pack barn so you have to be really reliant on bedding for example, and the weeks he's really happy that place looks spectacular, there's fresh straw, there's all this stuff done and you're like “oh that's great. Everything's going back on track’ and then the next week, this week when I was back there it was like total disaster. Didn't clean anything, didn't do anything… He was really down and I think that really plays a role in the success of their operation, for sure.” {P63}

The impact of high stress and poor mental health on productivity was commonly described as a vicious circle, where it decreased productivity, which then fueled additional stress, which led to feeling worse, which further contributed to poor productivity. As one participant shared of some of the farmers they work with:

“…depending on how much they're feeling stressed they just mentally can't focus, can't be productive because they just feel like they're drowning, and then that just again compounds the problem because then they're not being productive, or getting stuff done, which then means the next day they just feel worse.” {P70}

An inability to contribute to farm operations as a result of mental health challenges was also common. As one participant shared, “I'm battling this and my wife is not in the barn because she can't get out of bed and so you're losing manpower too” {P72}. Another said, “I didn't have anybody really to help me, and I came to ask my husband if he could, and he couldn't get out of bed to help me.” {P73}

3.4.2. Decreased animal productivity and (or) animal welfare

Farmers’ high stress and poor mental health were reported to impact their productivity and ability to perform to usual standards, which in some instances, led to sub-par animal husbandry and care. For example, one participant said, “I think when it was at its worst we maybe didn't do a lot of those little extra things that we used to do. You know, we didn't wash the cows as often or little things like that” {P44} and another shared, “I think he just would do the bare minimum… it became too overwhelming to do a good job.” {P58}

Participants also described decreased animal production as a result of poor farmer mental health (e.g., “I would say if you're stressed out and you're working with cattle or pigs, or whatever, any livestock—then you're gonna stress the livestock out and it's gonna affect your impact [production]” {P61}).

Other participants shared:

“I was… anxious I guess. I had no tolerance for the cattle. Like if one cow kicked at me or whatever, I was mad right away. I had no tolerance for that kind of stuff and that obviously if you treat your cattle poorly they're not gonna milk as good as if you treat them with some care and consideration.” {P39}

“I won't lie to you, it was weird to see how the cows sensed it from you and they dropped in their milk and it just wasn't good and then now that everything's getting back on the right track, cows are happier and we're happier and the milk is better and stuff like that. So yeah, I mean, you know, we let a lot of things slip 'cause, you know, you got out and milked them, and you fed them, and you did the basics but the rest of the day you just kind of didn't feel like doing nothing so. So that was the biggest thing I think, you just didn't feel like doing the extras that made things better.” {P46}

In rare instances, participants described situations where poor farmer mental health escalated to tragic situations of animal neglect or abuse, “to the point where a major intervention needed to happen for both the people and the animals under their care” {P9}. For example:

“I've had producers that have just walked out of the barn one day because they just cannot cope and have left the animals. And the families have had to come in, in emergency situation to take over the milking, taking over the feeding of the animals so that [the animals’] welfare was looked after.” {P72}

“Well it's just the guy didn't feed the pigs. The pigs all died. So we were going into the barn and all we're seeing is – I forget I don't know I think it was 500, 600 sow operation that nothing left. Just the carcasses, and what got me is that he was a well-respected producer in the area and I know the person. I said what? There's no fricking way… There's got to be huge, huge problems emotionally for you to not feed animals and to know that it takes one phone call and those animals will be fed and you just decide “I'm not feeding them”, right?” {P10}

Contrary to situations described above, other participants explained the strong sense of happiness, pride, and meaning and purpose that their animals provided them as being key contributors to their ability to “keep going”. As one participant described of their episodes of depression, “I've gone through depression myself but the only thing that kept me getting off the couch or getting out of bed was going I have to feed my animals. I have to go look after them.” {P1}

3.4.3. Financial consequences

Financial consequences associated with participants’ high stress and poor mental health were commonly reported to include decreased profit via decreased farmer and animal productivity, but also through an inability for farmers to manage their farm and finances during the period of mental health challenge. As one participant explained, a fellow farmer’s mental health struggle that led to a decline in animal care, which led to poor milk quality: the “sad part about that is at one point the milk truck fined him and they wouldn't pick up his milk anymore.” {P9}

Another participant shared:

“Oh, [poor mental health] loses money like crazy. He doesn't pay his bills, he's got interest rates, he's got, you know, collection agencies. It's like – it really compounds, and adds up. At first it doesn't seem like such a big deal. It's like “oh, no big deal. I'll pay that next month” and then I think it gets to the point it's like, “oh, but since I didn't then sell those animals… I lost money on those. I've got to pay for the feed” and he doesn't have any money left over for himself so the whole farm kind of falls apart.” {P58}

Farmers’ stress and poor mental health contributed to additional financial implications like making it more challenging to secure needed financial loans. As one agricultural bank lender described:

“In some situations it made it hard for me to do my job because the mental health concern or issue was so large that until that issue was addressed I couldn't do my job. I couldn't help them financially. I was concerned about the day to day viability even of some of these farms.” {P5}

3.4.4. Scaling back of farm business or ending farming operations

The chronic stress and (or) experience of poor mental health led some farmers to question their life in farming. As one participant shared,

“I'm tense, I get stressed out, I get angry a lot faster. I don't want to be here, I find. Like I don't want to leave but I don't want to be here but there's nowhere to go. So yeah, when it's really stressful, it's like you just wonder why you're doing this. You really second guess everything and I just don't want to be here and I wonder why anybody would want to do this sometimes.” {P54}

As a means of coping with their stress or poor mental health, several farmers described “paring down” or reducing farm operations (e.g., “They pared the operation back down so that they could manage it” {P5} and “I think at some point you just have to start to reduce it a little bit, you know? Maybe I won't milk 60 cows anymore. Maybe I'll milk 50, try to do a good job” {P12}).

In other cases, the stress of farming and the impact on mental health led to farmers questioning staying in farming (e.g., “I thought the only way out of this is putting a for sale sign at the end lane and just having a simple life, because we do not have a simple life” {P14} and “The stress of my job is overwhelming. I mean, I'm at the point where that's what is gonna make me retire. It's not gonna be my health, it's gonna be my stress that I experience on this job” {P49}).

Several participants discussed situations of completely “walking away” and leaving farming altogether (e.g., “I've had to give up farming which was a lifetime goal for me and it just became unbearable to do” {P20}). A participant shared this experience she had with her husband,

“The first time my husband had a breakdown he wanted to sell the cows and I said no, not until he was back on track and then that was the decision we would make. So we kept them after the first time. The second time he wanted to sell the cows and get out of dairy and I said okay, when you get better now we'll talk about getting out because it was too much for him when he had these breakdowns. It was too hard on him, and it was too hard on the family and myself to keep the farm running as it needed to continue on.” {P53}

4. Discussion

The purpose of this research was to help address an important gap in knowledge on the lived experience of high stress and poor mental health among farmers, as well as the resultant ramifications. Unsurprisingly, the reported effects of stress and poor mental health on physical health and cognition in farmers are similar to that reported among the general population elsewhere; it is unlikely that there would be unique physiological responses that set farmers apart from the general population in terms of the effects of stress. Where this study expands our understandings is through thick, rich description of the impacts of stress and poor mental health in farmers via that altered physical health and cognition. Specifically, this study reports far-reaching and interconnected impacts of high stress and poor mental health on the farmers themselves, the people and animals in their lives, and most aspects of their farms, farming operations, financial viability, and farm success.

Personal impacts on farmers included lost personal drive and motivation, which had significant ramifications for their farm operations. While animal care was prioritized among livestock farmers we interviewed, it was common for participants to describe neglecting other farm responsibilities, including bookkeeping, paying bills, and beyond-basic animal care when under the influence of high stress or experiencing poor mental health. In response, avoidant coping behaviours (i.e., “efforts oriented toward denying, minimizing, or otherwise avoiding dealing directly with stressful demands” (Holahan et al. 2005), including alcohol and substance use, as well as self-isolation or withdrawal from others were often described, and served to exacerbate the issues and prevent farmers from getting the care they need. Elevated high-risk alcohol consumption has previously been reported among farmers in Australia (Brumby et al. 2013) and data collected from Canadian farmers after the present study (and during the COVID-19 pandemic) showed higher mean alcohol consumption and a higher proportion of farmers with hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption compared to the general Canadian population (Thompson et al. 2022). A scoping review of global literature reported a higher prevalence of “risky alcohol consumption patterns” in farmers and farmworkers compared to the general population (Watanabe-Galloway et al. 2022). With the high volume of workload and stressors experienced by farmers on a daily basis, alcohol and substance use may provide an avoidant means of coping for some farmers; however, this style of coping can add more problems to the original issues they are trying to avoid. Indeed, avoidant coping behaviours have been associated with greater mental health and physical health symptoms (Penley et al. 2002), including poor self-rated health (Mauro et al. 2015), depressive symptoms (Cronkite and Moos 1995), and development of future chronic and acute stressors (Holahan et al. 2005).

High stress was also described to negatively impact sleep, and associations between poor sleep quantity and quality in farmers and numerous negative outcomes, including obesity and depression (Hawes et al. 2019) and on-farm injuries (Choi et al. 2006) have been reported. A positive association between stress, depression, and farm injury in a 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis (Jadhav et al. 2015) highlights the interplay between the experience of stress, poor mental health, and safety at work. Further, in some instances, the personal impacts of high stress and poor mental health among our participants included thoughts of suicide and suicide ideation. Suicide among farmers is an important societal concern; a 2016 meta-analysis of 32 studies globally that reported an excess risk of suicide among farmers, forestry, and fishery workers (Klingelschmidt et al. 2018) and a 2021 systematic review reported depression among the main factors related to farmer suicide (Santos et al. 2021).

Interpersonal impacts of high stress and poor mental health were commonly reported. Participants described negative impacts on their communication and relationships with others, including family members and members of the farm team. This was often associated with how farmers dealt (or did not deal) with their emotions of irritability, defensiveness, and anger. It is well recognized that job stress can impact interpersonal relationships (Repetti and Wang 2017). What may further set our participants, and indeed many farmers apart, is the close-knit tying together of family and business, where many farm families live and work together, all-day, every day, year-round. This close-knit nature of their relationships was described by our participants to further amplify the negative impacts, often harming the family unit and the business. In very rare instances, the issues were described to extend into domestic violence and (or) animal neglect or abuse. These findings suggest opportunity for stress management and emotional intelligence training. Goleman’s model of emotional intelligence includes knowing and self-managing one’s own emotions, and recognizing others’ emotions and managing relationships (Fernandez-Berrocal and Extremrea 2006). Given Goleman’s assertion that 80% of success in life can be attributed to emotional intelligence (vs. 20% intelligence quotient) (Goleman 2005), this may also prove a useful training for farm business and success. Exploration of the impacts of emotional intelligence training in farmers, using a measured and evidence-based approach (Fernandez-Berrocal and Extremrea 2006) would be useful.

Previous research has reported on some of the cognitive impacts of stress among farmers. For example, difficulty concentrating was a significant predictor of high stress among Canadian farmers (Walker and Walker 1987) and high stress was reported to negatively impact cognition among Latino farmworkers in the US (Nguyen et al. 2012). Difficulties with focus and decision-making were also signs reported by Australian financial counsellors with which to recognize high stress in farmers (Gunn and Hughes-Barton 2022). In our study, high stress and poor mental health were reported to have cognitive impacts, including difficulty making decisions and making poor decisions, which often had significant financial implications and (or) long-lasting impacts, in that a decision made today could continue to negatively affect the farm for several years thereafter. The reality of difficult problem-solving is similarly worrisome in that trouble-shooting issues is a daily requirement on most farms, with issues like machinery breakdown, animal ill-health or disease, logistics, etc. being common. Again, issues with trouble-shooting today could have long lasting implications for the farmers, animals, and farms. Many farmers responded to high stress and poor mental health by procrastinating or avoiding their responsibilities, naturally compounding their problems, which led to further procrastination and avoidance, and a vicious cycle ensued.

All of the personal, interpersonal, and cognitive impacts described by our participants were found to be interconnected and led to perceived impacts on farmers’ personal productivity, their animals’ productivity, and farm productivity. This is supported by extant research on the associations of farmer mental health with animal welfare and productivity. For example, higher dairy farmer occupational well-being scores were associated with higher scores on an animal welfare index, and vice versa (Hansen and Østerås 2019). A Canadian study of dairy cows found that higher farmer stress and anxiety scores were associated with higher prevalence of severe cow lameness and reduced protein content in cows’ milk (King et al. 2021). Further, serious animal welfare incidents are often associated with farmer mental health crisis (Kauppinen et al. 2010; Andrade and Anneberg 2014; Devitt et al. 2015). The personal and farm productivity impacts described by our participants naturally had financial consequences resulting from decreased farm outputs, procrastination paying bills, and acting as a barrier to securing financial loans.

In some instances, participants described the ramifications of high stress and poor mental health to lead them to significantly scale back their farm operations, and (or) leave farming altogether. This is in-line with studies from Australia, the Netherlands, and Norway that reported strong associations between declining well-being and the intention to exit farming among farmers and agricultural business owners (Gorgievski et al. 2010; Peel et al. 2016; Hansen 2022), although the difficulty in parsing out temporality (e.g., does poor well-being lead to poor farm success or vice versa?) and the interconnectedness of well-being with more commonly recognized reasons for leaving farming (e.g., pressures for farm expansion) were recognized. Our qualitative data presented here suggest that, for some farmers at least, poor well-being was a seminal factor in scaling back or exiting farming. Farmer attrition is a serious issue, both for the impacts on the farmers themselves, and given the increased need for expanded and sustainable farming to feed a growing global population (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) 2009). The FAO estimates that 60% more food production will be needed to feed a global population of 9.3 billion people, and solid arguments have been made that “doing that with a farming-as-usual approach would take too heavy a toll on our natural resources” (Graziano Da Silva 2012). We agree, and would further stress that the sustainability of farmers—via their mental health and well-being—must be highlighted as a critical factor in long-term sustainable food production. As evidenced by the data collected here, and recognized associations between well-being and personal productivity, animal welfare and production, and attrition from farming, not doing more to address the well-being of farmers would be a disservice to farmers and the global population alike.

The findings from this study support extant research with farmers in Canada and globally. In the 1980s, 140 participating farmers in Manitoba, Canada were given a list of physical and mental symptoms commonly associated with chronic stress and the five most frequently reported were “trouble relaxing, feeling tired most of the time, having trouble concentrating, low back pain, and losing my temper” (Walker et al. 1986). From a qualitative study with 20 male farmers in North Yorkshire, United Kingdom (UK) in the 1990s, Raine (1999) reported that stress caused farmers to experience difficulty sleeping, be irritable, not enjoy farming, and feel “down and anxious”, and these effects were reported to impact others in the family (Raine 1999). In the early 2000s, Parry et al. (2005) presented participating farmers in the UK with a checklist of physical and mental health symptoms during research interviews. Stress was reported to have negative effects on farmers’ mental and physical well-being, including sleep issues, back problems, worrying about work, irritability, and feeling down (Parry et al. 2005). Similarly, impacts of stress among 16 citrus growers in South Australia were reported in a 2009 paper to include depressive symptoms (e.g., feeling down/sad, loss of motivation, suicide ideation, withdrawing, negative self-talk, low self-esteem); neurotic symptoms (e.g., worrying, constant thoughts about work, nervousness); affective symptoms (e.g., frustration, disappointment, irritability); and physical symptoms (e.g., physical illness, tiredness) (Staniford et al. 2009). A 2019 paper describes using a structured questionnaire and semi-structured interview of 70 crop farmers in Nigeria and reported common effects of stress among participants to include physical (e.g., headaches, excessive tiredness, inability to sleep, back pain, relaxation problems) and cognitive/behavioural (i.e., forgetfulness, loss of temper, excessive worry) impacts (Olowogbon et al. 2019). The present study adds to our collective understandings of the issues arising from high stress and poor mental health in Canadian farmers and demonstrate widespread issues at multiple levels, including personal, interpersonal, animal, and farm.

To help ensure viable and sustainable agriculture, we must better attend to farmer mental health, helping reduce stressors and the impacts of stressors where possible. Previous reports have outlined in detail what approaches would be useful in Canada, including strategies to help address financial pressures and overwork (Canadian Agricultural Human Resources Council 2019; Parliament of Canada House of Commons Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food 2019). Increasing access to appropriate mental health care—tailored in a way that is likely to result in uptake by farmers—would also be helpful, as would “de-programming” of unhelpful beliefs around help-seeking and stigmatization of mental illness that some farmers may experience. Previous research has shown the need to custom-tailor services to farmers (Gerrard 2000; Rosmann 2005; Brumby and Smith 2009; Hagen et al. 2020). Training in communication and mental health literacy could also help agricultural communities identify issues earlier, potentially limiting impacts and improving prognoses. Existing programs like the Alcohol Intervention Training Program in Australia, potentially adapted for regional differences, may be useful to help farmers “adopt more positive alcohol-related behaviours” (Brumby et al. 2011), rather than using alcohol and other substances as a means of problem avoidance, as described by some of our participants here and noted in a recent survey of Canadian farmers (Thompson et al. 2022). Training in positive psychology skills (e.g., cognitive reframing, optimism, sleep hygiene) (Carr et al. 2021), stress management (Richardson and Rothstein 2008), coping strategies (Gunn and Hughes-Barton 2022), and resilience (e.g., eight themes described by Greenhill et al. (2009) could also help to limit the impact of occupational stressors and chronic stress, and give farmers tools to become healthier. For example, an online intervention (www.ifarmwell.com.au) that leads farmers through modules to build healthy coping strategies reduced stress and improvements in mental well-being among participants (Gunn et al. 2023). However, given a scarcity of published positive psychology interventions with farming populations, further research with farmers would be beneficial.

5. Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include a large sample size with inclusion of participants from a wide range of agricultural commodities, ages, and backgrounds, and use of multiple data validation techniques. Limitations of this study include interviewing only English-speaking farmers from Ontario, representing just one province in Canada, and limited representativeness in terms of participants’ genders and ethnicities. Participants from small commodity groups in Ontario might not have been represented in the initial recruitment as study information was shared via AWG networks; however, widespread social media was also used for recruitment. Due to the nature of the study, we are unable to infer temporality of associations from participants’ descriptions. For example, we are unable to ascertain whether high stress led some participants to experience poor sleep quality and quantity, or vice versa. The findings of this qualitative study cannot necessarily be extrapolated broadly, but rather serve to provide in-depth insights into farmers’ lived experiences. Finally, as these data were collected prior to the global COVID-19 pandemic, the lived experience of the pandemic, its associated factors, and potential long-term sequelae are not captured here.

6. Conclusion

Four main themes described high stress and poor mental health to impact farmers personally; interpersonally; cognitively; and professionally, including consequences for productivity, animals, and farm success. The perceived impacts are thus wide-reaching, extending beyond the individual affected farmers experiencing the issues, to the family and people they live and work with, often negatively impacting these relationships, sometimes irreparably. The cognitive impacts were described to seriously harm the operations of their farms, often with major financial and physical health consequences. Acting together, the personal, interpersonal, and cognitive impacts culminated to negatively impact farm operations, including implications for animal production and welfare and viability of the farm operation. Indeed, these issues were significant enough to lead to some farmers scaling back their operations or leaving farming altogether.

This research addresses important knowledge gaps, highlights the far-reaching impacts of high stress and poor mental health in farmers, and serves as a call to action for heightened attention and more importantly—action—on farmer mental health and well-being. If we want to strengthen Canadian agriculture, boost agricultural exports, and enhance agricultural sustainability, we must support the sustainability of the farmers themselves. The understandings of the impacts of high stress and poor mental health in farmers arising from this study can help enable health care practitioners to better serve their farmer patients, appeal to governments for more appropriate funding, supports, and resources, and help the many people working with farmers, and the public at-large, to better understand what farmers may experience in their service to society.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants for sharing their thoughts, feelings, and experiences with us for this study. We gratefully acknowledge the knowledge shared by our agricultural working group in the years leading up to this study. This research was funded by the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs—University of Guelph Partnership—Emergency Management Program, Egg Farmers of Ontario, Ontario Pork, Ontario Sheep Farmers, and the Ontario Federation of Agriculture.

References

Agriculture and AgriFood Canada, Government of Canada. 2023. Overview of Canada’s Agriculture and Agri-Food Sector. Available from https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/sector/overview [accessed 14 August 2023].

American Psychological Association. 2018. Stress effects on the body.pp. 1–11. Available from https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body [accessed 14 August 2023].

Andrade S.B., Anneberg I. 2014. Farmers under pressure. Analysis of the social conditions of cases of animal neglect. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 27: 103–126.

Bobo W.V., Grossardt B.R., Virani S., St Sauver J.L., Boyd C.M., Rocca W.A. 2022. Association of depression and anxiety with the accumulation of chronic conditions. JAMA Network Open, 5(5): E229817.

Booth N.J., Lloyd K. 2000. Stress in farmers. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 46(1): 67–73.

Braun V., Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2): 77–101.

Braun V., Clarke V. 2021. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. Routledge. pp. 201–216.

Brennan M., Hennessy T., Meredith D., Dillon E. 2022. Weather, workload and money: determining and evaluating sources of stress for farmers in Ireland. Journal of Agromedicine, 27(2): 132–142.

Brumby S., Chandrasekara A., McCoombe S., Kremer P., Lewandowski P. 2012. Cardiovascular risk factors and psychological distress in Australian farming communities. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 20(3): 131–137.

Brumby S., Kennedy A., Chandrasekara A. 2013. Alcohol consumption, obesity, and psychological distress in farming communities-an Australian study. Journal of Rural Health, 29(3): 311–319.

Brumby S., Kennedy A., Mellor D., McCabe M., Ricciardelli L., Head A., Mercer-Grant C. 2011. The Alcohol Intervention Training Program (AITP): a response to alcohol misuse in the farming community. BMC Public Health [Electronic Resource], 11(4): 242.

Brumby S., Smith A. 2009. “Train the trainer” model: implications for health professionals and farm family health in Australia. Journal of Agromedicine, 14(2): 112–118.

Canadian Agricultural Human Resources Council. 2019. How labour challenges will shape the future of agriculture: agricultural forecast to 2029.

Carr A., Cullen K., Keeney C., Canning C., Mooney O., Chinseallaigh E., O'Dowd A. 2021. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(6): 749–769.

Chida Y., Hamer M., Wardle J., Steptoe A. 2008. ‘Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival?’ 5(8): 466–475.

Choi S.W., Peek-Asa C., Sprince N.L., Rautiainen R.H., Flamme G.A., Whitten P.S., Zwerling C. 2006. Sleep quantity and quality as a predictor of injuries in a rural population. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 24(2): 189–196.

Cronkite R.C., Moos R.H. 1995. Life context, coping processes, and depression. In Handbook of depression. Edited by Beckham E., Leber W. 2nd ed. Guilford Press, New York. pp. 569–587.

Devitt C., Kelly P., Blake M., Hanlon A., More S.J. 2015. An investigation into the human element of on-farm animal welfare incidents in Ireland. Sociologia Ruralis, 55(4): 400–416.

Díaz Llobet M., Plana-Farran M., Riethmuller M.L., Rodríguez Lizano V., Solé Cases S., Teixidó M. 2024. Mapping the research into mental health in the farming environment: a bibliometric review from Scopus and WoS databases. Agriculture (Switzerland). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI).

Elliott M., Heaney C.A., Wilkins J.R. III, Mitchell G.L., Bean T. 1995. Depression and perceived stress among cash grain farmers in Ohio. Journal of Agricultural Safety and Health, 1(3): 177–184.

Favril L., Yu R., Uyar A., Sharpe M., Fazel S. 2022. Risk factors for suicide in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological autopsy studies. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 25(4): 148–155.

Fereday J., Muir-Cochrane E. 2006. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1): 80–92.

Fernandez-Berrocal P., Extremrea N. 2006. Emotional intelligence: a theoretical and empirical review of its first 15 years of history. Psicothema, 18: 7–12.

Firth H.M., Williams S.M., Herbison G.P., McGee R.O. 2007. Stress in New Zealand farmers. Stress and Health, 23(1): 51–58.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2009. How to feed the world in 2050. Rome, Italy. Available from http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/wsfs/docs/expert_paper/How_to_Feed_the_World_in_2050.pdf [accessed 22 November 2018].

Fraser C.E., Smith K.B., Judd F., Humphreys J.S., Fragar L.J., Henderson A. 2005. Farming and mental health problems and mental illness. The International journal of social psychiatry, 51(4): 340–349.

Gerrard N. 2000. An application of a community psychology approach to dealing with farm stress. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 19: 89–100.

Goleman D. 2005. Emotional intelligence: why it can matter more than IQ. 10th Anniv. Bantam Books, New York.

Gorgievski M.J., Bakker A.B., Schaufeli W.B., van der Veen H.B., Giesen C.W.M. 2010. Financial problems and psychological distress: investigating reciprocal effects among business owners. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(2): 513–530.

Graziano Da Silva J. 2012. Feeding the world sustainably. UN Chronicle, June, p. Vol. XLIX. Available from https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/feeding-world-sustainably [accessed 14 August 2023].

Green J., Thorogood N. 2018. Qualitative methods for health research. 4th ed. Sage Publications, London.

Greenhill J., King D., Lane A., MacDougall C. 2009. Understanding resilience in South Australian farm families. Rural Society, 19(4): 318–325.

Gregoire A. 2002. The mental health of farmers. Occupational Medicine, 52(8): 471–476.

Guba E.G., Lincoln Y.S. 1994. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Handbook of qualitative research. Edited by Denzin N., Lincoln Y. Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks. pp. 105–117.

Gunn K.M., Hughes-Barton D. 2022. Understanding and addressing psychological distress experienced by farmers, from the perspective of rural financial counsellors. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 30(1): 34–43.

Gunn K.M., Skaczkowski G., Dollman J., Vincent A.D., Brumby S., Short C.E., Turnbull D. 2023. A self-help online intervention is associated with reduced distress and improved mental wellbeing in Australian farmers: the evaluation and key mechanisms of www.ifarmwell.com.au. Journal of Agromedicine, 28(3): 378–392.

Hagen B.N.M., Harper S.L., O'Sullivan T.L., Jones-Bitton A. 2020. Tailored mental health literacy training improves mental health knowledge and confidence among Canadian farmers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11).

Hansen B.G. 2022. Stay in dairy? Exploring the relationship between farmer wellbeing and farm exit intentions. Journal of Rural Studies, 92(4): 306–315.

Hansen B.G., Østerås O. 2019. Farmer welfare and animal welfare-exploring the relationship between farmer’s occupational well-being and stress, farm expansion and animal welfare. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 170(1): 104741.

Hawes N.J., Wiggins A.T., Reed D.B., Hardin-Fanning F. 2019. Poor sleep quality is associated with obesity and depression in farmers. Public Health Nursing, 36(3): 270–275.

Holahan C.J., Holahan C.K., Moos R.H., Brennan P.L., Schutte K.K. 2005. Stress generation, avoidance coping, and depressive symptoms: a 10-year model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4): 658–666.

Hounsome B., Edwards R.T., Hounsome N., Edwards-Jones G. 2012. Psychological morbidity of farmers and non-farming population: results from a UK survey. Community Mental Health Journal, 48: 503–510.

Jadhav R., Achutan C., Haynatzki G., Rajaram S., Rautiainen R. 2015. Risk factors for agricultural injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Agromedicine, 20(4): 434–449.

Jones-Bitton A., Best C., MacTavish J., Fleming S., Hoy S. 2020. Stress, anxiety, depression, and resilience in Canadian farmers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(2).

Jones-Bitton A., Hagen B., Fleming S.J., Hoy S. 2019. Farmer burnout in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24): 5074.

Kallioniemi M.K., Simola A., Kaseva J., Kymäläinen H.R. 2016. Stress and burnout among Finnish dairy farmers.Journal of Agromedicine, 21(3): 259–268.

Kauppinen T., Vainio A., Valros A., Rita H., Vesala K.M. 2010. Improving animal welfare: qualitative and quantitative methodology in the study of farmers’ attitudes. Animal Welfare, 19: 523–536.

Kearney G.D., Rafferty A.P., Hendricks L.R., Allen D.L., Tutor-Marcom R. 2014. A cross-sectional study of stressors among farmers in Eastern North Carolina. North Carolina Medical Journal, 75(6): 384–392.

King M.T.M., Matson R.D., DeVries T.J. 2021. Connecting farmer mental health with cow health and welfare on dairy farms using robotic milking systems. Animal Welfare, 30(1): 25–38.

Klingelschmidt J., Milner A., Khireddine-Medouni I., Witt K., Alexopoulos E.C., Toivanen S., et al. 2018. Suicide among agricultural, forestry, and fishery workers: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 44(1): 3–15.

Low J. 2019. A pragmatic definition of the concept of theoretical saturation. Sociological Focus, 52(2): 131–139.

Lowe J., Griffith G., Alston C. 1996. Australian farm work injuries: incidence, diversity and personal risk factors. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 4: 178–189.

Marin M.F., Lord C., Andrews J., Juster R.P., Sindi S., Arsenault-Lapierre G., et al. 2011. Chronic stress, cognitive functioning and mental health. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 96(4): 583–595.

Mauro P.M., Canham S.L., Martins S.S., Spira A.P. 2015. Substance-use coping and self-rated health among US middle-aged and older adults. Addictive Behaviors, 42: 96–100.

Meier S.M., Mattheisen M., Mors O., Mortensen P.B., Laursen T.M., Penninx B.W. 2016. Increased mortality among people with anxiety disorders: total population study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(3): 216–221.

Nguyen H.T., Quandt S.A., Grzywacz J.G., Chen H., Galván L., Kitner-Triolo M.H., Arcury T.A. 2012. Stress and cognitive function in Latino Farmworkers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 55(8): 707–713.

Olowogbon T.S., Yoder A.M., Fakayode S.B., Falola A.O. 2019. Agricultural stressors: identification, causes and perceived effects among Nigerian crop farmers. Journal of Agromedicine, 24(1): 46–55.

Parliament of Canada House of Commons Standing Committee on Agriculture and Agri-Food. 2019. Mental health: a priority for our farmers. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Parry J., Barnes H., Lindsey R., Taylor R. 2005. Farmers, farm workers and work-related stress. Health and Safety Executive Research Report 362.

Peel D., Berry H.L., Schirmer J. 2016. Farm exit intention and wellbeing: a study of Australian farmers. Journal of Rural Studies, 47: 41–51.

Penley J.A., Tomaka J., Wiebe J.S. 2002. The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine.

Prosser J. 2011. Visual methodology: toward a more seeing research. In The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. Edited by Denzin N., Lincoln Y. Sage Publications Ltd, Thousand Oaks. pp. 479–496.

Raine G. 1999. Causes and effects of stress on farmers: a qualitative study. Health Education Journal, 58: 259–270.

Reissig L., Crameri A., von Wyl A. 2019. Prevalence and predictors of burnout in Swiss farmers—burnout in the context of interrelation of work and household. Mental Health and Prevention, 14: 200157.

Repetti R., Wang S. 2017. Effects of job stress on family relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13: 15–18.

Richardson K.M., Rothstein H.R. 2008. Effects of Occupational Stress Management Intervention Programs: a meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(1): 69–93.