Boundary spanners catalyze cultural and prescribed fire in western Canada

Abstract

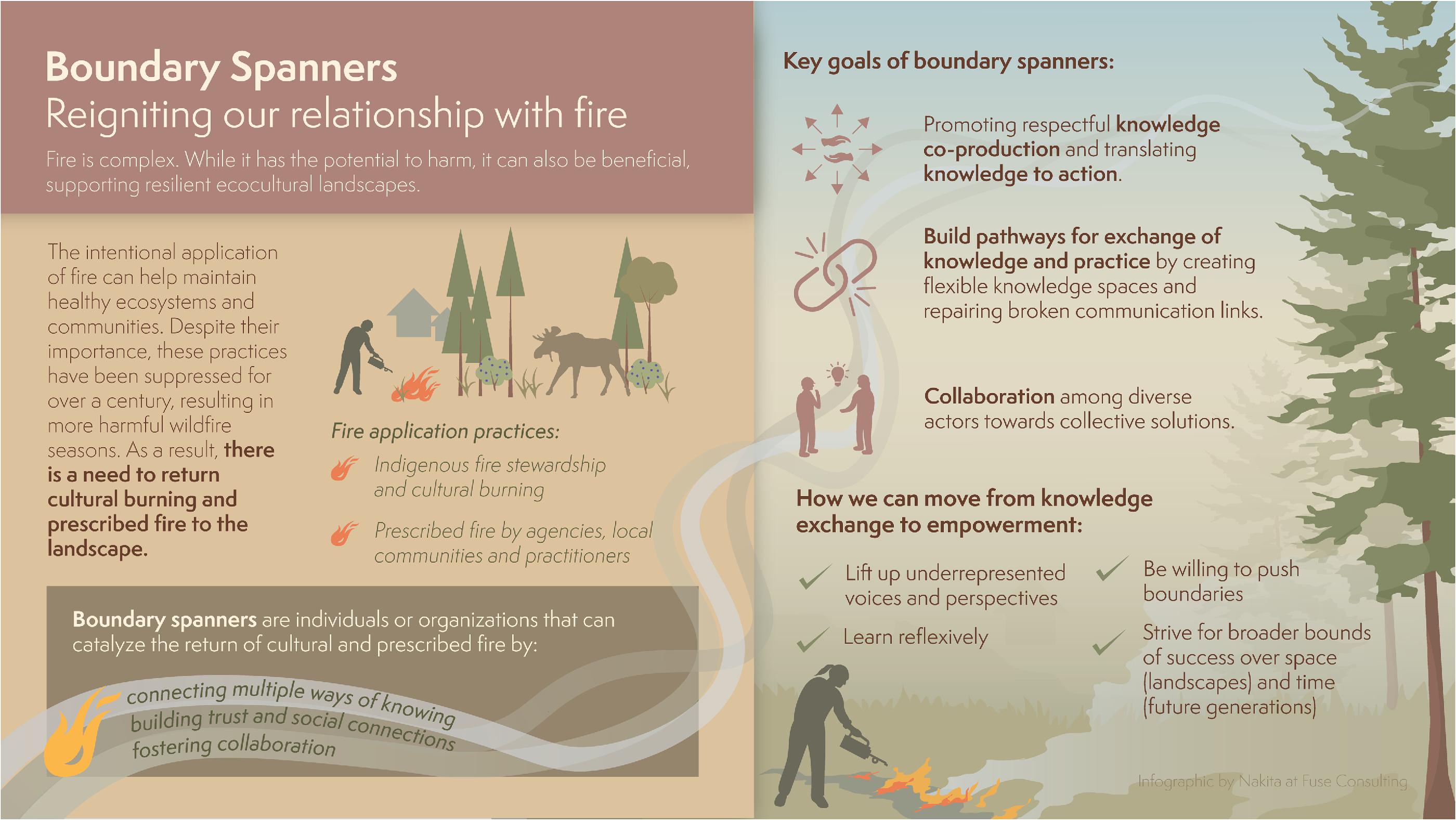

Western Canada is increasingly experiencing impactful and complex wildfire seasons. In response, there are urgent calls to implement prescribed and cultural fire as a key solution to this complex challenge. Unfortunately, there has been limited investment in individuals and organizations that can navigate this complexity and work to implement collaborative solutions across physical, cognitive, and social boundaries. In the wildfire context, these boundaries manifest as jurisdictional silos, a lack of respect for certain forms of knowledge, and a disconnect between knowledge and practice. Here, we highlight the important role of “boundary spanners” in building trust, relationships, and capacity to enable collaboration, including through five case studies from western Canada. As individuals and organizations who actively work across and bridge boundaries between diverse actors and knowledge systems, we believe that boundary spanners can play a key role in supporting proactive wildfire management. Boundary spanning activities include: convening workshops, hosting joint training exercises, supporting knowledge exchange and communities of practice, and creating communication tools and resources. These activities can help overcome unevenly valued knowledge, lack of trust, and outdated policies. We need collaborative approaches to implement prescribed and cultural fire, including a strong foundation for the establishment of boundary spanning individuals and organizations.

Introduction

In western Canada, the increasing frequency and severity of wildfire is leading to growing negative impacts on human and ecological communities (Coogan et al. 2019; Hagmann et al. 2021). The challenge of managing wildfire is particularly complex because it is dynamic—threatening human lives, environmental values, and infrastructure, while also maintaining and promoting the diversity and resilience of ecosystems (Hoffman et al. 2022a). Complexity also arises from uncertainties related to interactions between climate change and the legacies of past management practices (Tymstra et al. 2020). Furthermore, management decisions are often constrained by jurisdictional and geographical boundaries and institutions and knowledges that typically operate in disconnected silos (e.g., distinct disciplines in western science, applied practitioner knowledge, and Indigenous knowledge and science) (Safford et al. 2017; Copes-Gerbitz et al. 2022). Addressing this modern wildfire challenge not only requires spanning boundaries to facilitate greater collaboration among a diversity of actors and disciplines, but also working across knowledge systems to produce actionable information that can inform equitable decision-making (Colavito et al. 2019; Davis et al. 2021; Copes-Gerbitz et al. in review).

Navigating this complexity is particularly challenging in the revitalization and application of prescribed and cultural fire, which has become a priority for many communities and levels of government to address the growing risk of wildfire in western Canada (Canadian Council of Forest Ministers 2016; Abbott and Chapman 2018; Sankey 2018; Canadian Council of Forest Ministers Wildland Fire Management Working Group 2021). Many Indigenous communities, for example, are seeking to implement cultural burning as part of broader processes of cultural revitalization and (re)assertion of sovereignty (Dickson‐Hoyle et al. 2021; Nikolakis and Ross 2022). However, contemporary efforts to support cultural and prescribed fire are constrained by several factors. These include disparate knowledge systems and expertise that are unevenly valued or accredited across colonially constructed organizations, agencies, and scientific disciplines (Hoffman et al. 2022b). Furthermore, a widespread lack of trust between Indigenous knowledge holders and government decision-making authorities poses challenges for more recent initiatives designed to guide the application of fire that is informed and co-produced by both Indigenous knowledge and western science (Dickson‐Hoyle and John 2021; Hoffman et al. 2022b). Building trust through respectful and effective knowledge exchange among the diversity of actors working to implement prescribed and cultural fire is therefore critical (Coleman and Stern 2018; Colavito et al. 2019; Goodrich et al. 2020; Davis et al. 2021). Collaboration is also key for developing actionable changes to policies that currently constrain who, where, how, and when prescribed and cultural fire can be applied (Hoffman et al. 2022b; Clarke et al. 2023).

In this perspective, we highlight the critical role of “boundary spanners” in facilitating collaboration and knowledge co-production to promote the application of cultural and prescribed fire. The contributions of boundary spanning individuals and organizations to collaborative fire management and applied wildfire research are increasingly recognized in the United States, such as in Fire Science Exchange Networks and Cooperative Extension Programs (Kocher et al. 2012; Davis et al. 2021; Grimm et al. 2022). While not without challenges, including connecting with Indigenous knowledge holders, (Collins et al. 2022), these examples from the United States demonstrate the importance of dedicated boundary spanner programs, not just projects. In western Canada, the value of boundary spanning is not widely acknowledged, which means there are few dedicated boundary spanning individuals, networks of practitioners, or organizations. Further, although there is growing recognition of the importance of boundary spanners or extension specialists more broadly, their role and contributions remains poorly understood (Goodrich et al. 2020). This lack of understanding leads to boundary spanners continuously being overlooked and undervalued (Bednarek et al. 2018), even when they play a critical role in supporting and implementing cultural and prescribed fire.

We represent a collaborative group of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous fire researchers, knowledge holders, and practitioners working and living in western Canada who each perform boundary spanning roles through our diverse professional and personal roles (please see accompanying positionality statement). Through our work, we have witnessed and experienced the chronic undervaluing of boundary spanners, including burnout (Crosno et al. 2009) and lack of professional recognition or institutional support for boundary spanning activities (Bednarek et al. 2018; Goodrich et al. 2020), which often occur “off the side of the desk.” In academia, for example, there is a greater recognition of products and outputs (particularly published papers) over processes (including knowledge sharing activities), the latter of which are a main focus of boundary spanners. These issues are exacerbated when boundary spanners are expected to facilitate long-term collaborative processes, but also produce immediate results to address the short-term urgency of wildfire or the demands and timelines of academic or funding requirements. Furthermore, boundary spanning activities are increasingly expected of individuals who do not have adequate training and experience in facilitation and mediation, or who lack the collaborative ties or resources to support relationship building with diverse actors and knowledge holders (Tushman and Scanlan 1981; Goodrich et al. 2020).

While boundary spanners are often defined as either individuals or organizations that play a bridging role between producers and users of science (Safford et al. 2017; Colavito et al. 2019; Grimm et al. 2022), in this paper we extend this definition to highlight the functions of boundary spanners in promoting collaboration, collective action, and knowledge co-production among diverse knowledge holders. In doing so, we offer a novel contribution to the boundary spanning literature, broadening its scope beyond the (western) science-policy interface and emphasizing the critical contributions of Indigenous and local knowledges and actors to fire research and practice. First, we examine the scope of boundary spanners and identify key needs for boundary spanning roles and functions to facilitate the application of cultural and prescribed fire in western Canada. We then describe examples of boundary spanning individuals and organizations currently working at the intersection of science with Indigenous knowledge and practice in the context of prescribed or cultural fire in western Canada. Finally, we highlight how addressing the current wildfire challenge requires investing in boundary spanning individuals and organizations through dedicated positions, enhanced job scope for specific training and qualifications, and allocated time in positions to undertake critical boundary spanning work.

Boundary spanning for collaboration and knowledge co-production

The concept of boundary spanning originated in the organizational science and management literature, with a focus on specific organizational roles and functions that support information processing and relationships across organizational boundaries (Aldrich and Herker 1977; Tushman and Scanlan 1981; Kapucu 2006). This concept was later expanded to also include individuals (both within and outside formal organizations) who intentionally situate their work to connect across different boundaries (Tushman and Scanlan 1981; Williams 2002; Bednarek et al. 2018). Boundary spanning individuals and organizations can cross technical (e.g., methodological), physical (e.g., geographic, technology, communication systems), cognitive (e.g., differences in understanding, worldviews, knowledge, disciplines or language) and social (e.g., trust, norms, professional or social identity) boundaries, which can be barriers to mutual understanding and collaboration (Long et al. 2013; Termeer and Bruinsma 2016; Safford et al. 2017; Jesiek et al. 2018). Importantly, both boundary spanning individuals and organizations exist across a spectrum of formality, often depending on whether boundary spanning activities are a priority; some function in clearly defined, dedicated, and supported roles or organizations, whereas others may incorporate boundary spanning activities into their work, despite not being recognized or supported in doing so (Aldrich and Herker 1977; Coleman and Stern 2018). Given the role of both individuals and organizations, the variety of boundaries being spanned, and the spectrum of formality, boundary spanners interface across a range of scales (Buizer et al. 2016), including in fire contexts (Davis et al. 2021).

A growing body of literature has examined the role of boundary spanners working at the science-policy interface to strengthen relationships between producers and users of science, and to guide evidence-informed decision-making (Kocher et al. 2012; Bednarek et al. 2018; Grimm et al. 2022). The increasing focus on knowledge co-production, defined as the “collaborative process of bringing a plurality of knowledge sources and types together to address a defined problem and build an integrated or systems-oriented understanding of that problem” (Armitage et al. 2011, p. 996), is driven by the recognition that complex sustainability challenges such as climate change and wildfire require collaborative solutions that span boundaries (Termeer and Bruinsma 2016; Bednarek et al. 2018; Carey, Landvogt and Corrie 2018). Furthermore, boundary spanners themselves can be experts who help create, facilitate, and translate unique knowledge and scientific outcomes (Davis et al. 2021). By connecting processes and actors across different types of boundaries, boundary spanners strengthen collaboration by fostering trust, mutual understandings and shared problem definitions, and facilitating knowledge exchange and translation (Termeer and Bruinsma 2016; Coleman and Stern 2018; Satheesh et al. 2022).

Building trust among actors and promoting respectful knowledge co-production requires attending to issues of equity and unequal power relations (Goodrich et al. 2020), and moving beyond informing and consulting towards empowering (Bamzai-Dodson et al. 2021). Research examining boundary spanners working at the science-policy interface specifically focuses on their role in linking the producers and users of scientific knowledge, and developing actionable scientific outputs through activities such as convening forums, hosting training exercises, supporting knowledge networks and communities of practice, policy advocacy, and creating and sharing communications tools and resources (Buizer, Jacobs and Cash 2016; Colavito et al. 2019; Goodrich et al. 2020). These information-sharing and knowledge exchange activities involve more than simply disseminating information; boundary spanners actively reframe, translate and mobilize information across boundaries for different contexts or audiences (Jesiek et al. 2018), iteratively and adaptively filling identified knowledge gaps and ensuring outcomes are useful. Furthermore, attending to issues of equity requires examining perceived or real power imbalances (Goodrich et al. 2020), which can help move boundary spanning from the science-policy interface into the knowledge-practice interface by including forms of knowledge not often recognized as “science.” Through efforts to facilitate knowledge co-production, boundary spanners can also support collaborative decision-making capacity, equipping individuals and organizations with tools to work towards collective solutions (Bamzai-Dodson et al. 2021).

Supporting boundary spanning roles requires efforts to support boundary spanning organizations and individuals. Specifically addressing rigid organizational structures that have not included knowledge translation and extension as part of an organization’s core mission or strategic plan is key (Buizer, Jacobs and Cash 2016; Djenontin and Meadow 2018). Simultaneously, effective boundary spanning individuals must have the skills, experience and subject matter expertise to convey legitimacy, understand the language and realities of different physical, cognitive, and social contexts, and respectfully connect with relevant professionals and experts in their field (Tushman and Scanlan 1981; Colavito et al. 2019). For example, qualities such as empathy, emotional intelligence and an openness to learning and improvising are key attributes of a boundary spanner (Long et al. 2013; Termeer and Bruinsma 2016; Goodrich et al. 2020). In addition, boundary spanners must be skilled in developing and sustaining social connections and trust both within and outside of their own sphere (Mell et al. 2022) and to mediate between different interests (van Meerkerk and Edelenbos 2018). As such, boundary spanning should not be viewed as an entry-level position (Colavito et al. 2019) or equivalent to communications or facilitation roles. Instead, leadership within organizations should support boundary spanning as a distinct individual skill and practice by providing professional development opportunities and training to technically and culturally competent staff, prioritizing long-term investment of time and resources into boundary spanning activities, and integrating these roles and functions into existing organizational and decision structures (Buizer, Jacobs and Cash 2016; Bednarek et al. 2018; Goodrich et al. 2020).

Boundary spanners can support cultural and prescribed fire in western Canada

Cultural burning is one facet of Indigenous fire stewardship that involves the intentional application of fire by Indigenous knowledge holders for diverse objectives following specific cultural protocols and teachings transmitted across generations (Lake and Christianson 2019). Cultural fire has been a part of western Canada’s landscapes for millennia, although its application was limited through a combination of colonization and fire suppression policies starting in the late 1800s (Christianson et al. 2022; Hoffman et al. 2022b). Prescribed burning, in contrast, is the intentional application of fire, usually by agencies, consultants, and industry, for silviculture, fuel management and/or ecological objectives (Hoffman et al. 2022b). Throughout western Canada, communities and governments are looking to revitalize the use of cultural and prescribed fire to address the growing threat of more frequent and severe wildfires (Lewis et al. 2018; Sankey 2018; Xwisten Nation et al. 2018; Dickson‐Hoyle et al. 2021; Nikolakis and Ross 2022; BC Ministry of Forests 2022). However, siloes between multiple forms of fire knowledge and a lack of trust between practitioners and agencies continues to pose barriers to implementation (Hoffman et al. 2022b; Clarke et al. 2023). These barriers are reinforced by the boundaries between the diverse technical, geographical, cognitive, and social contexts within which fire is embedded. Boundary spanning individuals and organizations are thus critical to facilitate the creation of two-way knowledge and practice exchange pathways required to support collaborative and proactive approaches to revitalizing cultural and prescribed fire at different scales.

Numerous inquiries (e.g., Abbott and Chapman 2018; Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs 2018) and research strategies (e.g., Sankey 2018) in Canada highlight the value of Indigenous and local fire knowledge and expertise, and the importance of incorporating these into both research and management. Improved understanding of fire effects on both ecosystems and cultural values is also important for supporting the application of prescribed and cultural fire. However, there is the persistent risk that Indigenous and local knowledge is simply extracted from the cultures and contexts in which they are embedded, to be “integrated” into government-led prescribed or cultural fire initiatives (Hoffman et al. 2022b). Despite the growing attention to Indigenous fire stewardship, and the willingness of Indigenous leaders and communities to create a shared future of fire stewardship, agency expertise continues to be privileged over Indigenous fire knowledges or expertise (Dickson‐Hoyle and John 2021). Therefore, there is a need to support networks of boundary spanners and boundary spanning activities that can promote respectful processes of knowledge co-production among scientific and Indigenous experts, and fire managers and policymakers. Critically, this work must happen across scales (e.g., provincial, regional, local) to ensure that local-level solutions (e.g., cultural and prescribed burning) are enabled by higher-level mandates and policy instruments (e.g., legislation, regulations, policies) (Hoffman et al. 2022b). Furthermore, while there have been calls for enhanced contributions from the social sciences (Sankey 2018), fire research and management in western Canada is predominantly informed by western natural sciences. Boundary spanners can also play a key role in promoting transdisciplinary and problem-centered research and in translating information to derive actionable insights that can inform policies and practices for cultural and prescribed fire.

In western Canada, complex organizational and jurisdictional boundaries also result in the siloing of knowledge and expertise, and pose barriers to collaborative decision-making across scales. For example, since the 1990s in British Columbia (BC), decision-making for fire management and forest management on “Crown” land has been the statutory responsibility of two different organizations: the (current) BC Wildfire Service and the Ministry of Forests, respectively (Copes-Gerbitz et al. 2022). This separation of decision-making, coined the “big divorce,” disconnected expertise between the two intertwined topics, such that for the last 30 years objectives for fire have often been made with minimal consideration of the objectives of forestry, and vice versa (Copes-Gerbitz et al. 2022). In addition, this separation contributed to the decline in prescribed (especially broadcast) burning, as forestry practitioners received less support for burning while simultaneously grappling with concerns over liability and smoke (Copes-Gerbitz et al. 2022; Hoffman et al. 2022a). These issues are further exacerbated in the context of cultural burning, which aims to achieve both fire-related and forestry-related objectives, among other cultural objectives, but must contend with and navigate different organizational requirements (Lake and Christianson 2019; Hoffman et al. 2022b). Today, the complex and contested jurisdictions throughout Indigenous territories, over which Indigenous peoples continue to assert Rights and Title, limit the ability of Indigenous communities to implement cultural burning (Hoffman et al. 2022b).

Collectively, these legacies have created mistrust and barriers to collective action among governments and communities. Boundary spanning individuals and organizations can help to navigate these barriers at different scales by building trust between Indigenous and provincial leadership and fire experts in forums to identify shared values, objectives, and opportunities for shared decision-making; facilitating agency cross-training or collaborative training opportunities to build mutual capacity and share expertise; and connecting research with decision- and policy-makers to highlight diverse expertise and pathways needed to enable prescribed and cultural fire (Shindler et al. 2014).

Learning from boundary spanning in western Canada

Below, we highlight the contributions of several boundary spanning organizations and programs supporting collaboration and knowledge co-production in cultural and prescribed fire in western Canada. These contributions, written by individuals who are doing boundary spanning work within their organizations, demonstrate the importance of boundary spanning functions such as filling knowledge gaps, co-producing knowledge, building capacity, and developing trust and relationships. They also highlight diverse pathways of boundary spanning that emerge from place-based practice, and the importance of dedicated boundary spanning individuals and organizations (Fig. 1). Although the case studies below are unique to the places in which they are embedded in western Canada, they offer learnings on the range of boundary spanning activities implemented by individuals and organizations that may be broadly applicable to other contexts.

Fig. 1.

1. Building relationships through art: BC Wildfire Service Cariboo Region and local artists

Since widespread wildfires burned in the Cariboo Region of south-central BC in 2017, a priority for local BC Wildfire Service staff has been to support the revitalization of prescribed burning in collaboration with Indigenous peoples. Doing so required new, more respectful ways of learning and two-way communication. In a new approach for meaningful engagement with Indigenous communities, staff from the BC Wildfire Service partnered with a local artist and art educator to facilitate reflective, community-based art sessions focused on storytelling and sharing different worldviews about fire and cultural burning. These creative storytelling-through-art conversations were held as a series of three to five sessions at three different Indigenous communities in the Cariboo Region in 2022. Indigenous community members, including Elders, youth, Firekeepers, knowledge holders, and families were invited to attend and express their connection to land, values, and stories through multi-media artwork. Participants were invited to use the charcoal from fire-affected bark, natural colours from local plants, and various paints to tell their stories associated with fire. In one case, the local artist did a live drawing of place-based engagement in a forest where a cultural burn was being planned, to capture the spirit of collaboration and importance of grounding conversations in place (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The storytelling-through-art sessions provided an environment for shared learning and mutual understanding, which helped to start building the trust and respectful relationships necessary for revitalizing cultural burning in the Cariboo Region. For example, discussions included important values associated with fire, priority locations for revitalizing cultural burning, cultural considerations such as ceremony and intergenerational knowledge transmission, and capacity-building for Indigenous fire crews, topics that are not normally discussed when planning government-sponsored burns. Staff from the BC Wildfire Service and local land managers learned about cultural burning from the perspective of Indigenous knowledge holders and stewards. Important pathways were established for cross-cultural and institutional support of prescribed burning with Indigenous peoples, crossing cognitive boundaries of different worldviews of fire and ways of knowing. Considered a success by all participants, art sessions will continue to be an important part of collaborative planning to revitalize cultural burning.

2. Filling practitioner knowledge gaps: The Wildland Fire Ecology & Management Program

The Wildland Fire Ecology & Management (WFEM) program is a new continuing education certificate offered by the University of British Columbia (UBC)—Okanagan Campus. The WFEM program was conceptualized in 2019 during a meeting of wildfire experts, including First Nation, academic, government, and industry partners who discussed barriers to implement proactive fire management. Three primary limitations to innovative fire management were identified: (1) the lack of training in fundamental principles of fire ecology from both Indigenous and western science perspectives; (2) the need to translate and extend these knowledges to applied fire management; and (3) the need to provide training to a broad and diverse group of professionals who are increasingly involved in fire management and risk mitigation. To address these limitations, the WFEM program seeks to cross cognitive boundaries between science and practice as well as Indigenous and western knowledges, and cross physical boundaries by providing learning opportunities to people from multiple regions and sectors. Potential participants in the WFEM program include (but are not limited to) Indigenous and non-Indigenous firefighters, wildfire managers, government employees, foresters, resource managers, ecologists, biologists, and urban planners, each of whom plays an important role in addressing current and future challenges in fire management.

Designed to embody the principles of Two-Eyed Seeing (Wright et al. 2019), Indigenous and western knowledges are braided and spanned throughout this three-part program. Participants receive the cross-cultural training needed to understand (1) the fundamentals of fire ecology and practice, (2) the role of fire in variable landscapes and across Indigenous territories, and (3) the complex history and contemporary relationship of people and fire. Focused on wildfire in western Canada, the program broadens the scope of applied knowledges beyond the boreal forest to include fuel types and potential fire behavior unique to western montane forests, and ecosystem-specific tools and techniques for developing fire prescription plans that are inclusive of cultural fire values. Asynchronous, online delivery reduces barriers (e.g., distance and time) and financial costs, while providing an experiential learning environment for participants from diverse backgrounds spanning territories, jurisdictions and agencies. The curriculum is presented using place-based case studies and interviews with collaborators, with reflective learning activities demonstrating the application of tools. The program culminates with a capstone project in which participants use the newly acquired knowledge and tools to develop and communicate a fire plan for their own community.

Boundary spanners were essential during the development, implementation, and ongoing curriculum updates. To ensure the WFEM program provided both Indigenous and western science perspectives, the curriculum was developed by Indigenous Firekeepers and biophysical and social scientists from UBC. Additional input was provided by a scoping committee including representatives from multiple levels of government (First Nations, regional districts, and provincial), professional associations, forest industry, and wildfire management organizations. Continued collaboration and knowledge extension with these groups is essential to the success of the WFEM program, as new learning materials and field-based workshops are developed and implemented, fostering a fully integrated community of practice in fire ecology and management.

3. Knowledge co-production and capacity-building: First Nations Emergency Services Society

The First Nations Emergency Services Society (FNESS) of BC is working to build resilient Indigenous communities through an all-hazards approach to emergency management. FNESS originated in 1986 as the Society of Native Indian Fire Fighters of BC, with an objective to reduce the number of fire-related deaths on reservations. Today, FNESS incorporates six core business programs (Mitigation, Preparedness and Response, Recovery and Emergency Support Services, Fire Services, Decision Support, and Administration) to support emergency services for Indigenous communities. The FNESS main offices are in Kamloops on the traditional territory of the T'kemlúps te Secwépemc, a Secwépemc Nation community, and in North Vancouver on the traditional territory of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish Nation), but most of the 60+ employees work remotely to respond to place-based needs more effectively across the province. Many of these employees bridge important technical gaps and provide critical professional identities for Indigenous fire practitioners to support safer and healthier communities.

The FNESS Mitigation program includes revitalizing cultural and prescribed fire as a central goal. A key strategy to achieve this goal was to identify individuals with specific skills who could build collaborative relationships and trust with Indigenous communities. In 2022, FNESS hired two new Cultural and Prescribed Fire Specialists whose primary role is to develop relationships with Indigenous communities and better understand specific technical, cultural, and social needs required to revitalize cultural and prescribed fire. One outcome of having open, transparent and culturally appropriate communication was that several barriers were immediately identified with regard to building capacity and technical skills that were able to be directly and swiftly met by FNESS.

Through empowerment of fire practitioner identities in Indigenous communities, FNESS was able to act as a bridge and identify specific community needs. FNESS was then able to increase funding for wildfire risk mitigation, preparedness, and response funds to the most at-risk communities from the Department of Indigenous Services Canada and the BC Wildfire Service and Ministry of Forests. FNESS acts as the first point of contact for Indigenous communities, providing critical trust and relationships for partnerships with provincial and federal government agencies. In this way, they help cross technical boundaries of agency versus Indigenous approaches to fire and cognitive boundaries embedded in different languages (such as those within the Incident Command System versus Indigenous stewardship). For example, FNESS is a formal partner in the Department of Indigenous Services Canada First Nations Adapt Program, which supports research and practice to revitalize cultural burning by Indigenous communities in BC (e.g., Xwisten Nation et al. 2018).

4. Connecting science to practice: Canadian Prairies Prescribed Fire Exchange

The Canadian Prairies Prescribed Fire Exchange (CPPFE) is an inter-agency collective established to increase capacity for knowledge sharing and cross-training for prescribed fire as a conservation management tool. The CPPFE is based centrally in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, with partner groups spanning physical boundaries by working across three provinces, including Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. The CPPFE collaborates with fire practitioners from diverse backgrounds and experiences including landowners, communities, conservation groups, and experienced firefighters, helping to bridge a technical boundary where employees of government agencies often have access to more training and “certification” than non-government individuals. This initiative specifically provides opportunities for individuals that have been marginalized or underrepresented in fire management to learn about prescribed fire in a safe and respectful way.

The CPPFE acts as a strategic hub for grassland fire knowledge, bringing together expertise to fill training requirements and supporting knowledge exchange between experienced fire practitioners and individuals with place-based expertise. In October of 2022, the CPPFE held the first Canadian Prairies Training Exchange (TREX) event based in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Forty participants from 11 agencies and organizations attended, including students, conservation staff, wildland fire personnel, and fire departments. Participants brought knowledge and experience from all four western Canadian provinces. They engaged in diverse training opportunities throughout the week, and an ideal weather window allowed participants to burn seven prescribed fire units over five days (Fig. 3). This TREX, and similar events hosted by CPPFE, provide an opportunity for individuals to gain skills and partner organizations to build capacity, while simultaneously achieving fire management and conservation goals. Furthermore, TREX was an opportunity to share knowledge, develop and strengthen partnerships, and gain experience working in a complex multi-organization structure. Incorporating practitioners with a range of experience levels allows pairing of mentors with trainees to facilitate a one-on-one working environment. By identifying potential barriers around funding and training for prescribed fire, the CPPFE promotes and makes accessible emerging best practices and recommendations to increase the application of prescribed fire across grasslands in western Canada.

Fig. 3.

5. Empowering and building capacity for First Nations youth: Yukon First Nations Wildfire

Yukon First Nations Wildfire (YFNW) is a partnership of nine Yukon First Nations, including fire experts and their economic and community development corporations. A First Nations’ fire organization, YFNW was founded on the belief that Indigenous knowledge and innovative strategies can be incorporated into wildfire response and proactive fire management, crossing key cognitive and technical boundaries between different worldviews and approaches to fire. The YFNW creates opportunities for people from all walks of life, including the Warrior Program that was established to support at-risk youth throughout the territory. YFNW trains, manages, and employs all-hazard response crews, providing career opportunities in wildfire and fuel management, as well as flood mitigation and response and education in a practical setting. By focusing on youth, YFNW is developing their capacity as firefighters, community members, and future leaders, and crossing social boundaries by connecting different generations of fire practitioners.

Currently, YFNW is present in Yukon communities through the Initial Attack and Sustained Action wildland fire programs, and by providing specialized services such as fuel management. YFNW also provides wildfire response to northern communities in BC during extreme fire seasons. For example, in summer of 2018 when wildland fire threatened the community of Telegraph Creek, YFNW deployed a Wildfire Response Crew to support the Tahltan First Nation whose territory was impacted. This was the first formal agreement to provide mutual Nation to Nation support during an emergency situation and was the outcome of a long-term collaborative process bringing together the cultural expertise of individual Nations and identifying mutually beneficial solutions.

YFNW provides economic benefits to its First Nation Development and Community Corporation Partners and social benefits to Indigenous community members across the Yukon. This model allows the organization to concentrate on investing in youth and building programs that will help them excel in fire management, risk reduction, or other emergency response contexts. YFNW is working with partners at national, provincial/territorial, and local levels to facilitate conversations that address existing training gaps and expand response training and culturally appropriate certification standards across multiple hazards, including wildfire. YFNW’s short-term goals include revitalizing cultural burning in Yukon communities and continuing to develop the capacity of Yukon First Nations youth.

Enabling more boundary spanning for prescribed and cultural fire

The boundary spanning individuals and organizations featured above perform key roles, including: convening meetings and agreements; implementing projects; engaging in community outreach; leveraging funding support; planning projects; and sharing expertise (Huber-Stearns et al. 2022). Other examples stem from Indigenous and local communities who are finding innovative ways to bring more cultural and prescribed fire back to western Canada’s landscapes through collaborations while centering their local, place-based expertise (Christianson et al. 2014; Lewis et al. 2018; Xwisten Nation et al. 2018; Copes-Gerbitz et al. 2020; Dickson‐Hoyle et al. 2021; Hoffman et al. 2022b; Nikolakis and Ross 2022). The case studies presented here highlight the importance of boundary spanning led by individuals and organizations across different scales, including at local and regional (Cariboo fire art and YFNW), provincial (FNESS and WFEM Program), and cross-provincial scales (CPPFE). Through this multi-scalar approach, barriers to expanding cultural and prescribed fire—such as disparate knowledge systems and lack of trust—can more appropriately be addressed through aligned efforts.

There are also opportunities to learn from jurisdictions outside western Canada. In the United States, boundary spanning organizations such as the Joint Fire Science Program’s 15 Fire Science Exchange Networks financially support staff and connect researchers regionally to develop and communicate research that is responsive to policy and public needs. Another example is Cooperative Extension Programs, which are part of the Land-Grant University System, whereby faculty (usually campus-based) and regional (usually county-based) advisors span a continuum of scientific research and knowledge mobilization positions to address key information and practice gaps. For example, in the University of California system there are over 700 academic positions, of which 130 are campus-based cooperative extension faculty, 200 local county-based advisors across 57 local offices, and nine Research and Extension Centers throughout California. Specifically in a wildfire context, the Forestry and Natural Resource Program at Oregon State University supports six regional fire extension specialists who work directly with communities and practitioners to develop science-based products (e.g., webinars, fact sheets, academic publications), support partnership-building and policy change, and are embedded within the university in permanent positions to contribute to and communicate emerging science. While these examples of dedicated and well-funded organizations with a mission to enhance boundary spanning offer time-tested models and lessons, they also continue to grapple with settler-colonial roots, legacies, and ongoing impacts of the perceived superiority of western science. Land-grant universities, for example, were established through dispossession of Native American land and initially supported colonial ideals of “agriculture and mechanic arts” (Stein 2020). Similarly, the Joint Fire Science Exchanges continue to face challenges connecting with and representing Indigenous knowledge holders and practitioners (Collins et al. 2022). Recognizing and avoiding the re-creation of colonial systems will be critical to expanding boundary spanning in western Canada.

Boundary spanning individuals and organizations see a clear and immediate need to work collaboratively across knowledges, disciplines, and practices to support the widespread application of cultural and prescribed fire in western Canada (Fig. 1). In this paper, we highlight the boundary spanners that are developing and implementing place-based and solutions-oriented processes and tools to inspire additional boundary spanning activities. We also recognize that boundary spanning in wildfire is not new; programs such as Alberta’s Partners in Protection (the forerunner of FireSmart Canada), which started in the 1990s, were built to connect wildfire prevention and mitigation efforts and were early pioneers in this realm (McGee et al. 2015). Nevertheless, the negative impacts from recent and current wildfire seasons, and the public and political pressure that follows, are catalyzing new opportunities, funding sources, and collaborations that require boundary spanning experts and activities to enable cultural and prescribed burning. Similar to cases in the western United States (Huber-Stearns et al. 2022), these activities are allowing for more coordinated efforts to address complex wildfire challenges while emerging from, and responding directly to, diverse settings, contexts, and needs across western Canada.

A major outstanding challenge for many of the people and organizations engaged in boundary spanning efforts is that their work is undervalued, and is often not viewed by their organizations as part of their core job duties. This invisible labour, together with a lack of support and incentives, means there are few dedicated opportunities to build capacity and the necessary skills to engage in boundary spanning activities. Financial and professional development support, such as training time, are needed to develop skills such as relationship-building (e.g., facilitation, negotiation, mediation, and conflict resolution), communication with diverse audiences (e.g., accessible writing, communication, or design courses), and ethical practice (e.g., principles of Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession ). Furthermore, processes such as relationship-building and the development of relevant outputs take time, which is often not recognized or built into existing positions. For example, the expected or funded length of degree-granting programs are not typically flexible enough to allow for long-term relationship building. Relationship building and knowledge extension often fall into the categories of “extra” with many boundary spanners doing unpaid labour. Without incentivized opportunities, such as training and formal boundary spanning positions, western Canada will struggle to meet the growing demand for revitalizing cultural and prescribed fire.

Conclusions

Today’s wildfire challenges must be met by boundary spanning individuals and organizations willing and able to navigate the complexity of relationships, jurisdictions, and multiple landscape values and objectives. Boundary spanners need to be valued, prioritized, and utilized to enable more cultural and prescribed fire as innovative fire management solutions—both effectively and respectfully. Western Canada urgently needs more individuals, organizations, and dedicated positions to connect diverse knowledges, experiences, priorities, and perspectives of fire.

Statement of positionality

The views, positions, and examples presented in this paper represent the authors and when applicable (and with permission) the institution, organization, agency or Nation they represent. Amy Cardinal Christianson (Métis, she/her) and Dave Pascal (Lil'Wat First Nation, he/him) are Indigenous fire practitioners and scholars whose Nations’ knowledge extends millennia through intergenerational teachings. Jodi Axelson (she/her), Mathieu Bourbonnais (he/him), Kelsey Copes-Gerbitz (she/her), Lori Daniels (she/her), Sarah Dickson-Hoyle (she/her), Robert Gray (he/him), Kira Hoffman (she/her), Peter Holub (he/him), Nick Mauro (he/him), and Dinyar Minocher (he/him) are applied scientists, fire ecologists, social scientists, and/or fire practitioners who are not Indigenous. Collectively the authors have over 280 years of fire experience and are actively working to expand boundary spanning opportunities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank Dr. Jillian Harvey for reviewing this manuscript and providing important feedback. Thank you to Sarah Sigurdson for permission to share and showcase her artwork. This research was supported through a NSERC Postdoctoral grant to Hoffman and a NSERC-Canada Wildfire Research Network grant awarded to Daniels.

References

Abbott G., Chapman M. 2018. Addressing the new normal: 21st century disaster management in British Columbia. Victoria.

Aldrich H.E., Herker D. 1977. Boundary spanning roles and organization structure. Academy of Management Review. pp. 217–230.

Armitage D., Berkes F., Dale A., Kocho-Schellenberg E., Patton E. 2011. Co-management and the co-production of knowledge: learning to adapt in Canada’s Arctic. Global Environmental Change, 21(3): 995–1004.

BC Ministry of Forests 2022. 2022/23-2024/25 Service Plan. Available from https://www.bcbudget.gov.bc.ca/2022/sp/pdf/ministry/for.pdf [accessed November 2022].

Bamzai-Dodson A., Cravens A.E., Wade A., Mcpherson R.A. 2021. Engaging with stakeholders to produce actionable science: a framework and guidance. Weather, Climate, and Society, 1027–1041.

Bednarek A.T., Wyborn C., Cvitanovic C., Meyer R., Colvin R.M., Addison P.F.E., et al. 2018. Boundary spanning at the science–policy interface: the practitioners’ perspectives. Sustainability Science, 13(4): 1175–1183.

Buizer J., Jacobs K., Cash D. 2016. Making short-term climate forecasts useful: linking science and action. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(17): 4597–4602.

Canadian Council of Forest Ministers. 2016. Canadian wildland fire strategy: a 10-year review and renewed call to action.

Canadian Council of Forest Ministers Wildland Fire Management Working Group. 2021. A roadmap for implementing the Canadian wildland fire strategy using a whole-of-government approach. Available from http://cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/publications [accessed January 2022].

Carey G., Landvogt K., Corrie T. 2018. Working the spaces in between: a case study of a boundary-spanning model to help facilitate cross-sectoral policy work. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 77(3): 500–509.

Christianson A., Mcgee T.K., L'hirondelle L. 2014. The influence of culture on wildfire mitigation at Peavine Métis Settlement, Alberta, Canada, Society and Natural Resources, 27(9): 931–947.

Christianson A.C., Sutherland C.R., Moola F., Gonzalez Bautista N., Young D., Macdonald H. 2022. Centering indigenous voices: the role of fire in the boreal forest of North America. Current Forestry Reports, 8(3): 257–276.

Clarke L., Shapiro E., Sandborn C. 2023. Reducing wildfire damage by encouraging prescribed and cultural burning.

Colavito M.M., Trainor S.F., Kettle N.P., York A. 2019. Making the transition from science delivery to knowledge coproduction in boundary spanning: a case study of the Alaska fire science consortium. Weather, Climate, and Society, 11(4): 917–934.

Coleman K., Stern M.J. 2018. Boundary spanners as trust ambassadors in collaborative natural resource management. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 61(2): 291–308.

Collins N., Meldrum J., Schuster R., Burkardt N. 2022. 2021 Assessment of the Joint Fire Science Program's Fire Science Exchange Network. Virginia. Scientific Investigations Report 2022-5052. Available from https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2022/5052/sir20225052.pdf [accessed January 2023].

Coogan S.C.P., Robinne F.-N., Jain P., Flannigan M.D. 2019. Scientists’ warning on wildfire—a Canadian perspective. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 49(9): 1015–1023.

Copes-Gerbitz K., Sutherland I.J., Dickson-Hoyle S., Baron J.N., Gonzalez-Moctezuma P., Crowley M.A., et al. in review. Guiding principles for transdisciplinary fire research: insights from early-career researchers. Fire Ecology.

Copes-Gerbitz K., Daniels L.D., Hagerman S.M., Dickson-Hoyle S. 2020. BC community forest perspectives and engagement in wildfire management. Report to the Union of BC Municipalities, First Nations’ Emergency Services Society, BC Community Forest Association and BC Wildfire Service, Vancouver, Canada. Available from https://www.ubctreeringlab.ca/post/wildfire-management-in-bc-community-forests-2020 [accessed September 2020].

Copes-Gerbitz K., Hagerman S.M., Daniels L.D. 2022. Transforming fire governance in British Columbia, Canada: an emerging vision for coexisting with fire. Regional Environmental Change, 22(2): 1–15.

Crosno J.L., Rinaldo S.B., Black H.G., Kelley S.W. 2009. Half full or half empty: the role of optimism in boundary-spanning positions. Journal of Service Research, 11(3): 295–309.

Davis E.J., Huber-Stearns H., Cheng A.S., Jacobson M. 2021. Transcending parallel play: boundary spanning for collective action in wildfire management. Fire, 4(3): 1–20.

Dickson-Hoyle S., John C. 2021. Elephant Hill: Secwépemc leadership and lessons learned from the collective story of wildfire recovery. Secwepemcúl'ecw Restoration Stewardship Society.

Dickson‐Hoyle S., Ignace R.E., Ignace M.B., Hagerman S.M., Daniels L.D., Copes‐Gerbitz K. 2021. Walking on two legs: a pathway of indigenous restoration and reconciliation in fire-adapted landscapes. Restoration Ecology, 1–9.

Djenontin I.N.S., Meadow A.M. 2018. The art of co-production of knowledge in environmental sciences and management: lessons from international practice. Environmental Management, 61(6): 885–903.

Goodrich K.A., Sjostrom K.D., Vaughan C., Nichols L., Bednarek A., Lemos M.C. 2020. Who are boundary spanners and how can we support them in making knowledge more actionable in sustainability fields? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 42(June 2019): 45–51.

Grimm K.E., Thode A.E., Satink Wolfson B., Brown L.E. 2022. Scientist engagement with boundary organizations and knowledge coproduction: a case study of the Southwest Fire Science Consortium, Fire, 5(2).

Hagmann R.K., Hessburg P.F., Prichard S.J., Povak N.A., Brown P.M., Fulé P.Z., et al. 2021. Evidence for widespread changes in the structure, composition, and fire regimes of western North American forests. Ecological Applications, 31(8).

Hoffman K.M., Christianson A.C., Gray R.W., Daniels L. 2022a. Western Canada’s new wildfire reality needs a new approach to fire management. Environmental Research Letters, 17(6): 061001.

Hoffman K.M., Christianson A.C., Dickson-Hoyle S., Copes-Gerbitz K., Nikolakis W., Diabo D.A., et al. 2022b. The right to burn : barriers and opportunities for Indigenous-led fire stewardship in Canada. FACETS, 7, 464–481.

Huber-Stearns H.R., Davis E.J., Cheng A.S., Deak A. 2022. Collective action for managing wildfire risk across boundaries in forest and range landscapes: lessons from case studies in the western United States, International Journal of Wildland Fire, 31, 936–948.

Jesiek B.K., Mazzurco A., Buswell N.T., Thompson J.D. 2018. Boundary spanning and engineering: a qualitative systematic review, Journal of Engineering Education, 107(3): 380–413.

Kapucu N. 2006. Interagency communication networks during emergencies, The American Review of Public Administration, 36(2): 207–225.

Kocher S.D., Toman E., Trainor S.F., Wright V., Briggs J.S., Goebel C.P., et al. 2012. How can we span the boundaries between wildland fire science and management in the united states?, Journal of Forestry, 110(8): 421–428.

Lake F.K., Christianson A.C. 2019. Indigenous fire stewardship. Encyclopedia of Wildfires and Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) Fires, 1–9.

Lewis M., Christianson A., Spinks M. 2018. Return to flame: reasons for burning in Lytton First Nation, British Columbia. Journal of Forestry, 116(2): 143–150.

Long J.C., Cunningham F.C., Braithwaite J. 2013. Bridges, brokers and boundary spanners in collaborative networks: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 13(1).

McGee T., McFarlane B., Tymstra C. 2015. Wildfire: a Canadian perspective. Wildfire hazards, risks, and disasters, 35–58.

Mell J.N., Van Knippenberg D., Van Ginkel W.P., Heugens P. 2022. From boundary spanning to intergroup knowledge integration: the role of boundary spanners’ Metaknowledge and proactivity. Journal of Management Studies, 59(7): 1723–1755.

Nikolakis W., Ross R.M. 2022. Rebuilding Yunesit’in fire (Qwen) stewardship: learnings from the land. Forestry Chronicle, 98(1): 36–43.

Safford H.D., Sawyer S.C., Kocher S.D., Hiers J.K., Cross M. 2017. Linking knowledge to action: the role of boundary spanners in translating ecology, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 15(10): 560–568.

Sankey S. 2018. Blueprint for Wildland Fire Science in Canada (2019-2029). Edmonton, AB.

Satheesh S.A., Verweij S., Van Meerkerk I., Busscher T., Arts J. 2022. The impact of boundary spanning by public managers on collaboration and infrastructure project performance. Public Performance and Management Review, 0(0): 1–27.

Shindler B., Olsen C., Mccaffrey S.M., Mcfarlane B.L. 2014. Trust: a planning guide for wildfire agencies & practitioners—an international collaboration drawing on research and management experience in Australia, Canada, and the United States. p. 21.

Standing Committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs 2018. From the ashes: reimagining fire safety and emergency management.Available from http://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/INAN/Reports/RP9990811/inanrp15/inanrp15-e.pdf [accessed September 2019].

Stein S. 2020. A colonial history of the higher education present: rethinking land-grant institutions through processes of accumulation and relations of conquest, Critical Studies in Education, 61(2): 212–228.

Termeer C.J., Bruinsma A. 2016. ICT-enabled boundary spanning arrangements in collaborative sustainability governance. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 18, 91–98.

Tushman M.L., Scanlan T.J. 1981. Boundary spanning individuals: their role in information transfer and their antecedents. Academy of Management Journal, 24(2): 289–305.

Tymstra C., Stocks B.J., Cai X., Flannigan M.D. 2020. Wildfire management in Canada: review, challenges and opportunities. Progress in Disaster Science, 5, 100045.

Williams P. 2002. The competent boundary spanner. Public Administration, 80(1): 103–124.

Wright A.L., Gabel C., Ballantyne M., Jack S.M., Wahoush O. 2019. Using two-eyed seeing in research with indigenous people: an integrative review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1–19.

van Meerkerk I., Edelenbos J. 2018. Profiling boundary spanners. In Boundary spanners in public management and governance. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, Northampton. 93–112.

Xwisten Nation, Christianson A.M., Andrew D., Caverley N., Eustache J. 2018. Burn plan framework development: re-establishing indigenous cultural burning practices to mitigate risk from wildfire and drought. Canadian Institute of Forestry. Available from http://www.cif-ifc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/CIF_Xwisten_Nov2018_FINAL.pdf [accessed November 2018].

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

FACETS

Volume 9 • 2024

Pages: 1 - 11

Editor: Nicole Redvers

History

Received: 26 June 2023

Accepted: 19 January 2024

Version of record online: 4 July 2024

Copyright

© 2024 Authors Hoffman, Copes-Gerbitz, Dickson-Hoyle, Bourbonnais, Daniels, Gray, Mauro, Minocher, and Pascal; and The Crown. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Data Availability Statement

There are no datasets that accompany this perspective.

Key Words

Sections

Subjects

Plain Language Summary

The Role of Boundary Spanners in Advancing Collaborative Wildfire Management in Western Canada

Authors

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: KMH, KC, SD, JA, ACC, RWG

Data curation: KC, SD, MB, JA, PH, NM, DM, DP

Funding acquisition: KMH, KC, LDD

Investigation: KMH, KC, SD, JA, ACC, LDD, PH, NM, DM, DP

Methodology: KMH, KC, SD, MB

Project administration: KMH, KC

Resources: KMH, KC, SD

Supervision: LDD

Visualization: KMH, KC, DM

Writing – original draft: KMH, KC, SD, MB, JA, ACC, PH, NM, DM, DP

Writing – review & editing: KMH, KC, MB, JA, ACC, LDD, RWG, PH, NM, DM, DP

Competing Interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.

Funding Information

Canada Wildfire

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Other Metrics

Citations

Cite As

Kira M. Hoffman, Kelsey Copes-Gerbitz, Sarah Dickson-Hoyle, Mathieu Bourbonnais, Jodi Axelson, Amy Cardinal Christianson, Lori D. Daniels, Robert W. Gray, Peter Holub, Nicholas Mauro, Dinyar Minocher, and Dave Pascal. 2024. Boundary spanners catalyze cultural and prescribed fire in western Canada. FACETS.

9: 1-11.

https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2023-0109

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

Cited by

1. Wildfires are spreading fast in Canada — we must strengthen forests for the future