Taking care of knowledge, taking care of salmon: towards Indigenous data sovereignty in an era of climate change and cumulative effects

Abstract

In this paper, we argue that Indigenous data sovereignty (IDS) is vital for addressing threats to ecosystems, as well as for Indigenous Peoples re-establishing and maintaining sovereignty over their territories. Indigenous knowledge-holders face pressure from non-Indigenous scientists to collaborate to address environmental problems, while the open data movement is pressuring them to make their data public. We examine the role of IDS in the context of cumulative effects and climate change that threaten salmon-bearing ecosystems in British Columbia, guided by content from an online workshop in June 2022 and attended exclusively by a Tier-1 audience (First Nations knowledge-holders and/or technical staff working for Nations). Attention to data is required for fruitful collaborations between Indigenous communities and non-Indigenous researchers to address the impacts of climate change and the cumulative effects affecting salmon-bearing watersheds in BC. In addition, we provide steps that Indigenous governments can take to assert sovereignty over data, recommendations that external researchers can use to ensure they respect IDS, and questions that external researchers and Indigenous partners can discuss to guide decision-making about data management. Finally, we reflect on what we learned during the process of co-creating materials.

Introduction

Indigenous Peoples are leaders in conservation and environmental justice within Canada and globally. Non-Indigenous scientists and practitioners are increasingly recognizing that conserving biodiversity in the face of cumulative effects and climate change will require collaboration with Indigenous knowledge holders. While this recognition is long overdue, it is putting intense pressure on Indigenous Peoples to use their remaining land bases, limited through violent colonial dispossession, to solve environmental crises that were not of their making (Todd 2022; Brewer et al. 2023). The open data movement is adding additional pressure by failing to recognize that Indigenous Peoples are rights holders, not stakeholders, with the right to govern their data as they see fit (Carroll et al. 2019; Hudson et al. 2023). In this paper, we argue that Indigenous data sovereignty (IDS) is vital for addressing threats to ecosystems today, as well as for Indigenous Peoples re-establishing and maintaining sovereignty over their territories (refer to Table 1 for the definitions of key terms). To demonstrate this, we examine the importance of IDS for addressing cumulative effects and the impacts of climate change that are threatening salmon-bearing ecosystems in what is now known as British Columbia, Canada.

Table 1.

| Term | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Big data | Data amalgamated from multiple sources to create large-scale datasets to inform solutions to society-wide problems | Open Knowledge Foundation (2022) |

| Data | Attributes or properties that represent a series of observations, measurements, or facts that are suitable for communication and application | Smith (2016) |

| Data sovereignty | Managing information in a way that is consistent with the laws, practices, and customs of the nation-state in which it is located | Snipp (2016) |

| External researchers/scientists | A term we use (along with “non-Indigenous researchers/scientists”) to recognize that Indigenous Peoples are also scientists and researchers and to challenge the tendency to create a false binary between researchers and scientists versus Indigenous Peoples | Schnarch (2004); Younging (2018) |

| First Nations | In Canada, the term “First Nations” refers to a group of Peoples who were officially known as Indians under the Indian Act, which does not include Inuit or Métis Peoples. We use the term “First Nations” when speaking specifically to the project and findings we describe in this manuscript, which come from knowledge-holders and/or technical staff employed by Nations located within the colonial borders of what is now known as British Columbia | Vowell (2016) |

| Indigenous communities | When we refer to Indigenous communities throughout this manuscript, we are referring to communities in a broader sense (kinship, support, practice) that includes both urban and rural Indigenous Peoples, living within or away from their traditional territories | Peters and Andersen (2014) |

| Indigenous data | Any facts, knowledge, or information about an Indigenous Nation and its citizens, lands, resources, cultures, and communities, regardless of who collects it. Information ranging from demographic profiles to education attainment rates, maps of sacred lands, songs, and social media activities, among others | Carroll et al. (2019) |

| Indigenous data governance | The act of harnessing tribal cultures, values, principles, and mechanisms—Indigenous ways of knowing and doing—and applying them to the management and control of an Indigenous nation's data ecosystem. The mechanism by which Indigenous Nations can achieve IDS | Carroll et al. (2019) |

| Indigenous data sovereignty (IDS) | The right of Indigenous Peoples and Nations to govern the collection, ownership, and application of their own data (whether collected by Indigenous Nations themselves or external data agents), deriving from the inherent right of Indigenous Nations to govern their peoples, lands, and resources. Within international Indigenous rights frameworks, IDS is positioned as a collective right. Unlike the definition of data sovereignty, IDS is not limited by geographic jurisdiction or digital form | Carroll et al. (2019) |

| Indigenous knowledge | Knowledge created and/or mobilized by Indigenous Peoples that may include Traditional Ecological Knowledge and scientific knowledge. We recognize that there are multiple distinct Indigenous knowledges, but we use the singular term throughout the manuscript for readability | Berkes (2017); Reid et al. (2022a); TallBear (2014) |

| Indigenous Peoples | In the context of this manuscript, we use the term “Indigenous Peoples” when referring to all Indigenous Peoples in Canada (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Peoples) and globally, and when referencing general concepts that apply to across diverse and distinct Indigenous cultures and contexts (such as the term “Indigenous data sovereignty”). According to the United Nations, there are more than 5000 Indigenous groups globally, which represent more than 476 million people living in 90 countries | Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (2020) |

| Open data | Data that can be freely used, re-used, and redistributed by anyone—subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and sharealike | Open Knowledge Foundation (2022) |

| Scientific knowledge | Information that has been gathered and condensed into testable laws and principles through a systematic enterprise | Snively and Corsiglia (2016) |

| Tier-1 | First Nations in Canada engage and consult with external agencies and each other on fisheries management via a three-tiered process: Tier-1 discussions occur among First Nations only, while Tier-2 involves Nation-to-Nation discussions between federal Crown agencies and First Nations, and Tier-3 includes the Provincial and Federal Crown governments, First Nations, and third-party stakeholders. The workshop described in this manuscript was a Tier-1 process | The First Nation Panel on Fisheries (2004) |

| Traditional ecological knowledge | The culturally and spiritually based ways in which Indigenous Peoples relate to ecosystems, which reflect Indigenous systems of environmental ethics and scientific knowledge about environmental use resulting from generations of interactions | Tsosie (2018) |

| Webinar contributors | We refer to the people who attended the webinar as “contributors” instead of “attendees” or “participants” to recognize the active contributions they made to the knowledge shared during the webinar and to the materials produced post-webinar | N/A |

| Western science | Scientific knowledge with roots in the philosophy of Ancient Greece and the Renaissance, favouring reductionism and physical law | Brayboy et al. (2012) |

The well-being of biodiversity and social-ecological systems is disproportionately dependent on ongoing Indigenous stewardship of Indigenous lands and waters. Over 40% of the Earth's biologically intact landscapes are managed by Indigenous Peoples (Garnett et al. 2018), and Indigenous-managed lands host equal or greater biodiversity than protected areas around the world (Schuster et al. 2019). This high biodiversity is in many places directly attributable to ongoing Indigenous stewardship (Heckenberger et al. 2007; Cook-Patton et al. 2014; Fisher et al. 2019; Armstrong et al. 2021; Hoffman et al. 2021). Indigenous Peoples have shaped and been shaped by local environments for millennia and hold in-depth, place-based knowledge of the lands and waters they steward (Cajete 2000; Kimmerer and Lake 2001; McGregor 2004; Artelle et al. 2019; Armstrong et al. 2021; Jessen et al. 2022; Wickham et al. 2022). Through these deep relationships to place, Indigenous Peoples have developed adaptable, resilient approaches to resource use and stewardship practices that facilitate high biodiversity and support ecosystem functioning (Kimmerer and Lake 2001; McGregor 2004; Berkes 2017; Mathews and Turner 2017; Bird and Nimmo 2018; Armstrong et al. 2021). As others have argued, strengthening resurgent Indigenous governance may be the most equitable and effective way to address ongoing threats to biodiversity (Claxton 2015; Artelle et al. 2019; Johnson-Jennings et al. 2019; Pasternak and King 2019; Jacobs et al. 2022; Todd 2022; Leonard et al. 2023; Popken et al. 2023).

In Canada, the onset of settler colonialism violently disrupted many Indigenous stewardship practices and continues to impede Indigenous Peoples’ access to and control of their territories, undermining their ability to continue their stewardship (Menzies 2016; Snook et al. 2020; Atlas et al. 2021; Hessami et al. 2021; Dick et al. 2022). Despite this, many caretaking activities survived and are undergoing a resurgence (e.g., Brown and Brown 2009; Claxton 2015; Atlas et al. 2021; Cohen et al. 2021; Steel et al. 2021; Lamb et al. 2022; Reid et al. 2022b; Popken et al. 2023). As citizens of sovereign Nations1 with constitutionally recognized inherent rights per Section 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982 (Minister of Justice 1982), the rights of Indigenous Peoples supersede those of other Canadian citizens, including rights to IDS as recognized by the United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP; UN General Assembly 2007). These rights were encoded into provincial law in British Columbia by the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA; Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation 2019) and federal law in Canada by the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (Government of Canada 2021).

Given that Indigenous knowledge cannot be separated from Indigenous knowledge-holders or their lands and waters (McGregor 2004), the use of Indigenous data should not occur without recognizing the rights of Indigenous Peoples to govern the collection, ownership, and application of their data (Carroll et al. 2019; Brewer et al. 2023; Hudson et al. 2023). The First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) Principles of OCAP® (ownership, control, access, and possession) provide a framework for asserting these rights over Indigenous data in Canada (Schnarch 2004; FNIGC 2014). As discussed further below, non-Indigenous groups, particularly Western-trained scientists, have appropriated, misused, and misapplied Indigenous knowledge, both historically and contemporarily, often at the expense of Indigenous Peoples (Bruhn 2014; Rodriguez-Lonebear 2016; Snook et al. 2020; Smith 2021; Ignace et al. 2023). Indigenous communities may therefore understandably be wary of working with external researchers (FNIGC 2019; Smith 2021). Explicit incorporation of IDS ensures that Indigenous partners retain control over data by repositioning power to Indigenous Peoples (Carroll et al. 2019). Given that integrating Indigenous knowledge with Western science requires active partnerships with Indigenous Peoples and that Indigenous knowledge is a vital component for addressing climate change and its cumulative effects (IPBES 2019), it follows that IDS, as an expression of fundamental Indigenous rights (Hudson et al. 2023), is an obligatory component of sustainable resource management and biodiversity conservation.

Calls for the recognition and respect of IDS are intensifying at the same time as a growing push for open and big data (Table 1), causing tension for Indigenous knowledge-holders. The open data movement seeks to make “digital data available with the technical and legal characteristics necessary for it to be freely used, reused, and redistributed by anyone, anytime, anywhere” (Open Data Charter 2015). The movement has noble intentions; among other things, it seeks to increase transparency and reproducibility to hold data collectors and interpreters, including scientists and governments, accountable for their findings and how they spend taxpayer dollars (Huston et al. 2019). Nonetheless, the open data movement overlooks that Indigenous Peoples are rights holders, not stakeholders; they have the right to govern data about their people, lands, and resources, including decision-making about when, how, and why data are used, as well as how much control to exert over data (Carroll et al. 2019; Hudson et al. 2023). The big data movement builds on the open data movement by amalgamating open data to create large-scale datasets to solve “society-wide problems” (Cowan et al. 2014). However, this approach has the risk of overlooking the plurality of societies and exacerbates the problems facing populations for which data are lacking or have histories of misuse and abuse, including those of Indigenous, Black, and People of Color (Milner and Traub 2021). The increasing recognition that Indigenous data can inform environmental stewardship is pressuring Indigenous knowledge-holders to make data public at the same time as the open data movement is pressuring them to release control.

In British Columbia, ongoing threats to salmon-bearing watersheds provide an illustrative example of the necessity of IDS. First Nations in BC, most of which have never signed treaties recognizing Crown jurisdiction over their territories, have sustainably harvested Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) for thousands of years, supporting their needs for subsistence, livelihoods, culture, health, and wellbeing (Campbell and Butler 2010; Menzies 2016; Atlas et al. 2021; Bingham et al. 2021; Morin et al. 2021). Beginning in the mid-1800s, settler colonialism brought destructive land-use practices, as well as high commercial fishing pressure, and the introduction of canneries, and a shift from Indigenous-governed, often in-river fisheries to colonially managed mixed-stock ocean fisheries, all of which contributed to declines in salmon populations (Newell 1993; Atlas et al. 2021). Colonial land-use practices included industrial development, commercial forestry, mining, and agriculture, which continue to alter the quality and quantity of salmon freshwater habitats today, further contributing to the decline of wild Pacific salmon (Sergeant et al. 2022; Tulloch et al. 2022; Cunningham et al. 2023). In addition to threatening food security for many First Nations in BC (Nesbitt and Moore 2016), livelihoods, and future economic development (Reid et al. 2022a), declining populations of salmon also threaten sacred, reciprocal relationships between people, salmon, and rivers (Bingham et al. 2021; Carothers et al. 2021). Thus, not only has colonial management of salmon habitats decreased salmon abundance, but colonial fisheries management has decreased access to salmon fisheries and practices (Menzies 2016; Carothers et al. 2021; Steel et al. 2021; Reid et al. 2022). Empowering the ongoing Indigenous stewardship of salmon, including Indigenous control over Indigenous data, will be critical for the continuance and recovery of salmon populations and First Nations knowledge systems, and there are emerging efforts to co-create ways forward (Reid et al. 2021; Reid et al. 2022). However, again, increasing interest from non-Indigenous researchers hoping to partner with Indigenous Peoples, along with government mandates to “consider” Indigenous knowledge in Crown decision-making, is putting pressure on Indigenous community members, especially Elders (Canada Research Coordinating Committee 2019; Jessen et al. 2022; Brewer et al. 2023).

In this paper, we examine the topic of IDS in the context of addressing climate change and the cumulative effects threatening salmon-bearing watersheds in BC by combining the First Nations Principles of OCAP® (Schnarch 2004; FNIGC 2014) with emerging guidelines for respectfully co-creating knowledge (Adams et al. 2014; Kitasoo/Xai'xais Stewardship Authority 2021; Reid et al. 2021; Mussett et al. 2022).2 This manuscript was guided by content from an online workshop hosted by the Watershed Futures Initiative in June 2022, which provided an opportunity to identify possible steps forward, issue recommendations, and put those recommendations into practice. Both the workshop itself and the outputs from the workshop were co-produced by a diverse team of researchers, practitioners, and knowledge-holders (see Positionality Statement). The workshop took place in British Columbia, and apart from the note-takers and the coordination team, and it was attended exclusively by a Tier-1 audience (i.e., 43 individual First Nations knowledge holders and/or technical staff, including non-Indigenous people working for a nation). The experiences and lessons shared during the webinar and referenced within this paper come from individuals representing over 20 of the more than 200 First Nations in British Columbia (BC Assembly of First Nations 2023), but may also be applicable for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Peoples across BC and Canada, and Indigenous Peoples globally. We address three key objectives. First, we demonstrate that attention to data is required for ethical, responsible, and effective collaboration between Indigenous communities and external Western scientists and researchers aiming to address the impacts of climate change and cumulative effects affecting salmon-bearing watersheds in BC. Second, we provide steps that Indigenous knowledge-holders and their governments can take to work toward asserting sovereignty over their data, recommendations that external researchers can use to ensure they are respecting IDS, and questions that external researchers and Indigenous partners can discuss to guide decision-making about data management. Finally, we reflect on what we learned during the process of co-creating materials from the webinar.

1

We use the term “Nation” to describe sovereign Indigenous groups within the Canadian context, although the ideas developed here may also be relevant in other regions where other terminology is used to describe relevant Indigenous communities, bodies, or collectives.

2

We have intentionally avoided the term “best practices” here because, as others have pointed out (e.g., Johnson-Jennings et al., 2019; Mussett et al., 2022), “best practices” are a Western hierarchical concept that tends to elevate the role of non-Indigenous experts and communities, resulting in disadvantages for Indigenous Nations.

Literature review

Indigenous data, co-management of resources, and knowledge co-creation

Indigenous Peoples have always created, used, and cared for data (Carroll et al. 2021; Kovach 2021; Smith 2021; Jessen et al. 2022). Before settler colonialism, Indigenous Peoples governed their data via shared responsibilities, which ensured that Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing were passed from one generation to the next through practice-based activities, language, storytelling, art, and other forms of knowledge-sharing, and these responsibilities are still recognized today (Simpson 2004; Menzies 2016; Carroll et al. 2019; Kovach 2021). Unlike in Euro-Western conceptualizations of data, Indigenous data belong to the collective; they have been generated collectively across generations and tested over time, and a Nation's members share responsibilities to the Nation to ensure Indigenous data are passed to future generations (Cajete 2000; Simpson 2004; Kukutai and Taylor 2016; Carroll et al. 2019; Walter and Carroll 2021). In this sense, Indigenous data are fundamental to who Indigenous Nations are as Peoples (Smith 2016; Carroll et al. 2019). Indigenous data are also highly contextual in that its generation, stewardship, and application are place-based (Rodriguez-Lonebear 2016; Johnson-Jennings et al. 2019). Applying Indigenous data outside of its Peoples or place, for instance, by aggregating Indigenous data into large datasets, means that such nuanced context is lost. While non-Indigenous researchers may have good intentions, by collecting and seeking to make use of Indigenous data, they have created a need for Indigenous data governance to apply to external parties.

In North America, non-Indigenous scientists/researchers have a history of treating Indigenous knowledge-holders as research subjects, driving exploitation, mistrust, power imbalances, and inequality that persist today (Schnarch 2004; Houde 2007; Cohen et al. 2021; Smith 2021; Mc Cartney et al. 2022; Silver et al. 2022; Ignace et al. 2023). For example, non-Indigenous researchers have used Indigenous data without properly attributing or acknowledging it as coming from Indigenous Peoples, lands, and waters; Indigenous data have been stolen and used to enrich non-Indigenous peoples and Nations through bioprospecting and biopiracy; non-Indigenous people have interpreted Indigenous data without cultural or contextual knowledge; and non-Indigenous researchers have claimed authority over Indigenous Peoples through their interpretations of Indigenous data (Schnarch 2004; Smith 2021; Mc Cartney et al. 2022; Ignace et al. 2023). Today, Western approaches to data management have created three distinct but related needs for the management of Indigenous data to facilitate IDS: (1) government-to-government processes that recognize Indigenous data as being on equal footing with data collected using Western scientific methods; (2) safeguarding ID from misuse; and (3) high-quality data that meet the needs of Indigenous Peoples (e.g., data for governance) (Smith 2016; Carroll et al. 2019).

First, there is a need for government-to-government processes that recognize Indigenous data to be on equal footing with data collected using Western scientific methodologies (Rodriguez-Lonebear 2016; Carroll et al. 2019). In Canada, Indigenous Peoples have long pushed Crown governments to affirm UNDRIP and the various treaties between the Crown and some Nations by co-managing natural resources and establishing arrangements for respectful government-to-government decision-making arrangements. While the concept of IDS has always existed, the IDS movement first coalesced in response to the need to safeguard socio-economic data collected about Indigenous communities by non-Indigenous governments (Kukutai and Taylor 2016). This is a goal that is at apparent odds with the push for co-management of environmental resources, which, instead of safeguarding Indigenous data, emphasizes the need to make Indigenous data widely available so that it may be incorporated into environmental decision-making (Cohen et al. 2021). True government-to-government decision-making would empower Indigenous Nations to make decisions about how Indigenous data are used and would ultimately facilitate successful co-management.

Second, there is still a need to safeguard Indigenous data from misuse. While non-Indigenous scientists and Crown agencies are increasingly appreciating the inherent value of Indigenous knowledge systems, there is still a tendency to view Indigenous data (including Indigenous knowledge) through the lens of Western science, for example, as extractable, reducible, and “usable” in quantitative formats, leading to the exclusion of knowledge holders (Schnarch 2004; Simpson 2004; Houde 2007; Jessen et al. 2022). Western-trained scientists may not recognize the holistic nature of Indigenous knowledge and may attempt to extract pieces of the whole to make convenient scientific arguments. As a result, Indigenous data may be misinterpreted, utilized against Indigenous Peoples, or disregarded when it does not serve the private interests of the Crown (Simpson 2004; Houde 2007). Indigenous data may also be used in ways that violate cultural protocols; for example, some forms of Indigenous data cannot be shared with all people and all contexts, and many come with responsibilities such as reciprocity (Schnarch 2004; Simpson 2004; Tsosie 2018). In addition, Indigenous knowledge and worldviews are encoded, practiced, and passed on through Indigenous languages (Simpson 2004; Eckert et al. 2018), but research projects designed, conducted, and governed through Indigenous languages (e.g., Horsethief et al. 2022) are vastly eclipsed and outnumbered by those carried out in English, reflecting the far reach and deep impacts of linguistic imperialism and colonialism. Indigenous knowledge is almost certainly oversimplified when incorporated into Western scientific research and translated into English, further undermining the acquisition of accurate Indigenous data.

Finally, there is a need for high-quality data meeting the needs of Indigenous Peoples. Like all governments, Indigenous governments require reliable information that identifies and informs community needs (Schnarch 2004; Steffler 2016; Walter and Carroll 2021). In this context, quality data are those that are useful to Indigenous communities and support self-governance (Open North and BCFNDGI 2017), for example by enabling informed decision-making about a Nation's citizens, communities, and resources (Walter and Carroll 2021). Data collection led by Indigenous Peoples would likely collect different information and/or use different methodologies than data collected about them by non-Indigenous governments (Schnarch 2004; Steffler 2016). Areas that are of interest to Crown governments do not usually align with the interests of Indigenous Peoples (Walter and Carroll 2021), but environmental data may sometimes be an exception in that it could be useful for both Indigenous and Crown governments (see the discussion on IDS and salmon below for examples). In addition, data collected about Indigenous Peoples are often interpreted in ways that emphasize disparities (Walter 2013; Walter and Carroll 2021). By interpreting Indigenous data out of context or relying solely on Western quantitative methodologies, researchers may inadvertently produce deficit framings (Schnarch 2004; Walter 2013), which emphasize disparity, deficit, deprivation, dysfunction, and difference (also known as the 5Ds; Walter and Suina 2019).

Non-Indigenous people are increasingly working alongside Indigenous partners to co-produce knowledge, recognizing the shortcomings of extractive, top-down research practices (Adams et al. 2014; Alexander et al. 2021; Degai et al. 2022; Jessen et al. 2022; Ignace et al. 2023). There are many benefits to co-creating knowledge, including more effective decision-making about biodiversity conservation informed by actionable research outputs, improved environmental governance, and improved recognition of and respect for Indigenous knowledge, rights, and authority among non-Indigenous partners (Adams et al. 2014; Alexander et al. 2021; Reid et al. 2021; Degai et al. 2022). In addition, more diverse teams can reduce bias in research design and applications (Schnarch 2004). Still, while knowledge co-production can benefit all parties, it may lead to burdens on knowledge-holders who may already be managing an influx of requests on their time (Canada Research Coordinating Committee 2019; Jessen et al. 2022; Brewer et al. 2023). We find that the existing literature on co-producing knowledge with Indigenous partners could more explicitly consider IDS.

Open and big data movements

As noted above, the open data and big data movements are seeking to make data publicly available and to amalgamate data from multiple sources to create large-scale datasets, which they suggest will inform solutions to “society-wide problems” (Cowan et al. 2014). In Canada, the Crown government has been moving toward “Open Government” since 2012. This move seeks to make the government more accessible to everyone, with an emphasis on open data (Treasury Board of Canada 2019). The 2018-2020 National Action Plan on Open Government included a commitment to Indigenous Peoples:

“The Government of Canada will engage directly with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis rights holders and stakeholders to explore an approach to reconciliation and open government, in the spirit of building relationships of trust and mutual respect. This commitment has been purposefully designed to allow for significant co-implementation, encouraging First Nations, Inuit, and Métis rights holders and stakeholders to define their approaches to engagement on open government issues” (Treasury Board of Canada 2019).

There are important benefits to open, publicly available data. For example, making data and analyses publicly available may provide accountability for federally funded researchers by ensuring that results are verifiable (Huston et al. 2019). The big data and open data movements both create opportunities for future novel analyses, including meta-analyses that combine multiple datasets to expand analyses across broad spatial and temporal scales (Cowan et al. 2014; Huston et al. 2019; Mc Cartney et al. 2022). Open data may also help increase transparency in Crown government and decrease the risk of industry capture (Godwin et al. 2023). At the same time, the big data and open data movements also create new challenges for Indigenous Peoples working to assert sovereignty over their data and can undermine Indigenous sovereignty more broadly (Carroll et al. 2019).

Indigenous Peoples’ access to, control over, and ability to benefit from data are at risk from both open and closed data (Carroll et al. 2019). For example, if Indigenous data are excluded from large datasets that are used to inform policy, Indigenous Peoples may also be excluded from any benefits of the research. In genomics research, not including Indigenous Peoples renders them invisible and may mean that they do not benefit from emerging health technologies and advancements (Carroll et al. 2019; Mc Cartney et al. 2022). However, if Indigenous data are included in large-scale datasets without guidance from rights and interests frameworks, their representation may reflect bias in existing data ecosystems (TallBear 2013; Carroll et al. 2019). In addition, aggregating Indigenous data removes them from their contexts, which poses inherent unethical risks in Indigenous knowledge systems because the context is essential for subsequent interpretations and applications (Rowe et al. 2021). Both the big data and open data movements today operate under blanket data-sharing policies that violate several of the IDS-related rights stipulated in UNDRIP (Mc Cartney et al. 2022; Hudson et al. 2023; Ignace et al. 2023), including the rights to redress for “cultural, intellectual, religious and spiritual property taken without their free, prior and informed consent or in violation of their laws, traditions, or customs” (Article 11.2), to “maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions” (Article 31.1), and to “free, and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources” (Article 32.2) and “before adopting and implementing […] measures that may affect them” (Article 19) (Hudson et al. 2023; Ignace et al. 2023; UNDRIP Act Implementation Secretariat 2023).

The FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) Data Principles provide an example of the tendency for the open and big data movements to overlook IDS. These principles were created by a team of academics, industry representatives, funding agencies, and scholarly publishers who aimed to improve the guidelines for those “wishing to enhance the reusability of their data” (Wilkinson et al. 2016). In particular, the FAIR Data Principles were designed to enhance the ability of machines to find and use data while also supporting its reuse by individuals. In the words of the FAIR Data Principles’ developers, “All scholarly digital research objects–from data to analytical pipelines–benefit from the application of these principles, since all components of the research process must be available to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and reusability” (Wilkinson et al. 2016). Unfortunately, the FAIR Principles overlook the power differentials between external researchers and Indigenous Peoples, as well as the rights held by Indigenous Peoples to control their data (as recognized by UNDRIP) (Carroll et al. 2021; Ignace et al. 2023; Jennings et al. 2023).

Importantly, a movement toward open data does not have to be at odds with IDS. Instead, by paying attention to Indigenous data through centering and following Indigenous leadership, the big and open data movements could be an opportunity for the implementation of IDS (Mc Cartney et al. 2022). For example, in response to the FAIR Principles, the Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA) developed the CARE (Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics) Principles for Indigenous Data Governance in 2018 (Carroll et al. 2021). The CARE Principles are designed to be implemented alongside FAIR, to ensure that FAIR data usage aligns with Indigenous rights as interpreted by Indigenous communities, who choose the level at which their data are accessible to others (Carroll et al. 2021; Jennings et al. 2023). Eventually, the CARE Principles may be expanded to support the ethical use of data about specific communities (Carroll et al. 2021).

Indigenous data sovereignty in British Columbia and Canada

Within Canada, the First Nations-led movement for IDS coalesced around the Crown government publicizing health and socio-economic data about First Nations communities (Schnarch 2004; FNIGC 2019), although Indigenous Peoples have always expressed the need to define and control Indigenous data (e.g., Mauro and Hardison 2000; Rodriguez-Lonebear 2016). In BC, as elsewhere in Canada, data about First Nations Peoples have been used for purposes at odds with their best interests or benefit (Schnarch 2004; FNIGC 2019). While the Crown seeks to use data to inform decisions that are in the “public interest”, the Crown may define this in ways that harm First Nations (for example, to support building pipelines or hydroelectric dams, FNIGC 2022). There is also a dearth of information that is useful to First Nations and to inform their governance (FNIGC 2019; Walter and Carroll 2021); Nations need access to data to assess challenges facing their citizens and members and to identify solutions. Unethical research practices and misuse of data about First Nations Peoples have led to mistrust and a reluctance to share personal information and/or to engage with non-Indigenous researchers and governments (Schnarch 2004; Steffler 2016; FNIGC 2019, 2022; Jessen et al. 2022; Ignace et al. 2023). Despite repeatedly committing to building Nation-to-Nation relationships with First Nations (Prime Minister Justin Trudeau 2015, 2017, 2020, 2021), current practices by the Crown government undermine trust-building. For example, the Crown has frequently and consistently overcollected information about First Nations, as the Auditors General have pointed out repeatedly since 2002 (Schnarch 2004; FNIGC 2022). The Crown sells access to these data, including to third parties, and requires First Nations to pay and submit Freedom of Information Requests to access them, including information about First Nations fisheries (FNIGC 2022).

First Nations' sovereignty over information and data is crucial for changing these problematic paradigms and for Nations to achieve their goals for self-determination and self-governance (Rodriguez-Lonebear 2016; Carroll et al. 2019; FNIGC 2019; Brewer et al. 2023; Ignace et al. 2023). Recognizing this, in the early and mid-90s, in response to exclusionary data collection practices by the Government of Canada, First Nations leadership took concerted action to assert control and build capacity for data collection, management, and dissemination, leading to the creation of FNIGC and the Principles of OCAP® (Schnarch 2004; FNIGC 2014). More recently, the FNIGC is working to create Regional Information Governance Centres (RIGCs) to support First Nations communities in realizing the power of data and to assert ownership and control “over data that relates to their identity, their people, language, history, culture, communities, and Nations, both historic and contemporary” (FNIGC 2022). As of the 2021–2022 fiscal year, the FNIGC was working to create regional priorities for RIGCs within BC, with three core functions: statistical production services, data management services, and data capacity building services (FNPSS 2021; Hunter 2021). In addition, the 2021 Federal Budget allocated $73.5 million over three years beginning in 2021–2022 to work towards implementing a First Nations Data Governance Strategy and $8 million to support Inuit and Métis baseline data capacity and the development of Inuit and Métis Nation data strategies (Department of Finance Canada 2021).

The Supreme Court of Canada has recognized Indigenous Peoples’ right to self-government, including the right to data sovereignty (Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada 2018). In November 2019, the British Columbia provincial government passed DRIPA (Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation 2019), which established UNDRIP as the Province's framework for reconciliation; the federal government followed with the UNDRIP Act in 2021 (Government of Canada 2021). UNDRIP reaffirms the rights of Indigenous Peoples to control data about their peoples, lands, and resources (Davis 2016; Hudson et al. 2023; Ignace et al. 2023). Despite these recognitions, a recent report from the FNIGC concluded that “Canada's information regime poses a barrier to First Nations data sovereignty. This in turn impedes First Nations' exercise of good governance to, among other things, improve their health and well-being and retain their languages and cultures” (FNIGC 2022).

The BC First Nations Data Governance Initiative (BCFNDGI) considers the Government of Canada's dual commitments to reconciliation and open governance an opportunity for enacting solutions that are rooted in Nation-to-Nation dialogue and that center First Nations (Open North and BCFNDGI 2017). First Nations will need to set the terms of data ownership and stewardship to ensure they meet the needs of First Nations Peoples and communities and support self-determination (Open North and BCFNDGI 2017). For example, data-sharing and collaborations across First Nations could produce datasets with the power to inform decisions that benefit communities and ecosystems, facilitate knowledge and skill-sharing, strengthen relationship-building, and build Indigenous expertise in the production and management of data. At the same time, Nations will need to form governance mechanisms that allow for institutional oversight of research and data collection in First Nations communities (Rowe et al. 2021). Meeting this opportunity will require incorporating principles of IDS into open data policies, which are currently lacking in most existing open data frameworks. To address this, the BCFNDGI has called for an “Inter-Nation Open Data Charter” between Indigenous and colonial Nations, to acknowledge Nation-to-Nation relationships and IDS (Open North and BCFNDGI 2017).

Indigenous data and salmon

Pacific salmon in Canada provide a salient case study for examining the necessity of IDS. Salmon provide vital services for both people and ecosystems (Janetski et al. 2009). As a “cultural keystone species”, Pacific salmon play a foundational role in the culture of Indigenous Peoples across Western Canada (Garibaldi and Turner 2004; Mathews and Turner 2017; Carothers et al. 2021). Despite connecting First Nations and non-Indigenous communities across British Columbia, they face wide-ranging threats throughout their life cycles. Data about Pacific salmon are complex, spanning territories, interconnected systems, interacting threats, and competing jurisdictions. Adding to this complexity is the fact that the stressors affecting salmon are diverse, cumulative, and occur at disparate spatial scales. Moreover, in British Columbia, data about salmon are hotly contested (Viatori 2019).

First Nations need quality data about salmon systems that cover their entire life cycles, which would inform the governance of human activities impacting salmon and stewardship actions. Before colonialism, despite using technologies with the potential to over-exploit salmon resources such as fish weirs and traps (Stewart 1982; Walter et al. 2000), First Nations used data to inform management decisions that kept salmon populations flourishing (Newell 1993; Campbell and Butler 2010; Claxton 2015; Menzies 2016; Bingham et al. 2021; Carothers et al. 2021; Morin et al. 2021). By monitoring salmon returns, First Nations adapted the manner, amount, and allocation of harvesting practices to respond to fluctuating population levels, avoiding overexploitation (Walter et al. 2000; Claxton 2015; Menzies 2016; Atlas et al. 2021; Carothers et al. 2021; Morin et al. 2021). This care and attention to data enabled First Nations to care for Pacific salmon in ways that facilitated flourishing salmon populations across British Columbia.

Since the beginning of settler colonialism, the Crown and its agents—mainly the Department of Marine and Fisheries, which later became the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO)—have taken Indigenous data about salmon without consent to support the development of Canada's commercial fisheries sector. In the late 1800s, private industry used Indigenous data to inform where to install canneries, and when and where to fish certain waters (Newell 1993; Harris 2001). The Crown, backed by private industry and non-Indigenous fishers, weaponized these data against First Nations fishers and portrayed traditional fishing methods as unsustainable and destructive (Stewart 1982; Newell 1993; Walter et al. 2000; Menzies 2016). The Crown restricted First Nations’ access to salmon fisheries while simultaneously increasing access for cannery operators (Walter et al. 2000; Harris 2001; Menzies 2016). By banning traditional fishing methods and encouraging the use of industrial gear in their place, the Crown drove fishers to shift to using less sustainable gear types (Stewart 1982; Walter et al. 2000; Claxton 2015; Atlas et al. 2021; Silver et al. 2022). These exploitative policies have fomented mistrust among First Nations communities and disrupted Indigenous data infrastructure.

Today, DFO continues to be implicated in the misuse of data. Some First Nations have accused the DFO of cherry-picking or withholding data about threats to Pacific salmon or of using data to support industry over the interests of First Nations (e.g., Cox 2021; Simmons 2023). For example, the ongoing controversy about Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) aquaculture in British Columbia has been driven in part by the Crown's treatment of data (Viatori 2019; Godwin et al. 2023). DFO has been accused of suppressing “inconvenient” science to the benefit of the aquaculture industry in BC (Lavoie 2022; Woolf 2022; Godwin et al. 2023), despite research concluding that Atlantic salmon farms have introduced disease (Mordecai et al. 2021) and increased parasites such as sea lice (Krkošek 2010; Godwin et al. 2021a) to wild Pacific salmon populations (Krkošek et al. 2011; Miller et al. 2014). Most recently, a report from DFO used data from fish farm operators to conclude that while sea lice infestations have increased since 2013, there is no statistically significant association between Atlantic salmon farms and sea lice infestations in wild Pacific salmon populations (DFO 2023), a statement that independent scientists have widely criticized (Cruickshank 2023). Past research found that the fish farm industry undercounts sea lice, suggesting that the industry-collected data are unreliable (Godwin et al. 2021b). In the absence of trustworthy industry or government data, local First Nations collected Indigenous data about sea lice from Broughton Archipelago fish farms, yielding insights into lice developing resistance to treatment (Godwin et al. 2022). The lack of dependable data about sea lice and their impacts on wild Pacific salmon populations is just one example illustrating the need for data to inform First Nations’ stewardship of salmon in BC.

This example showcases the importance of IDS or open data in combatting potential industry capture by Crown regulators and decision-makers. In Canada, Crown governments have high “professional reliance”, where they rely on industries to do their monitoring and assessments of environmental risks. These industries are operating within First Nations territories. However, industry-collected data are often proprietary, and while some data are shared internally with Crown governments, they are not usually shared with First Nations for their free use. The Crown may then apply industry-gathered data selectively to further support industrial activities in First Nations territories, posing risks to the well-being of salmon and First Nations. The Crown's reliance on industry data and the lack of open data and IDS exclude First Nations and prevent them from continuing stewardship practices on their territories. Thus, the lack of open data or IDS may decrease the potential for balanced consideration of environmental risks to salmon ecosystems and the First Nations rights-holders who have stewarded salmon for millennia.

There is an urgent need for collaborative management that considers Indigenous data on at least the same level as data collected via Western scientific methods. In 2019, modifications to Canada's Fisheries Act (Bill C-68) added a directive for DFO to incorporate Indigenous rights and knowledge into fisheries management practices and to strengthen obligations to build partnerships with First Nations (Lefrance and Nguyen 2018; Claxton 2019). Meeting this directive will require explicit consideration of IDS in fisheries management (Claxton 2019). While fisheries professionals are echoing the calls for knowledge co-production (e.g., Cooke et al. 2021; Mills et al. 2022; Yua et al. 2022) and big or open data (Cowan et al. 2014; Merten et al. 2016) that are happening in broader research contexts, the importance of caring for data is often overlooked.

Materials and methods

The webinar Taking Care of Knowledge, Taking Care of Salmon: Indigenous data sovereignty was held on 2 June 2022, to identify tangible action steps and implementable recommendations for First Nations sovereignty and governance of Indigenous data related to cumulative effects and climate change in the salmon-bearing watersheds of British Columbia. The webinar was planned by a committee composed of Indigenous leaders from across BC, with a coordination committee providing logistical support (see Positionality Statement). This webinar was the second in the Indigenous Stewardship of Salmon Watersheds series. The first webinar, held in June 2021, brought together more than 50 contributors from Indigenous Nations across Western Canada to share their experiences related to cumulative effects and climate change in salmon-bearing watersheds. Among other key topics, contributors highlighted that IDS is a key requirement for First Nations as they work to steward salmon in their territories, leading to the webinar on IDS in 2022 and ultimately to this manuscript. See Supplementary Materials 1 for the full webinar agenda.

Positionality and contributions of authors

The authors are an interdisciplinary team composed of Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge-holders, scholars, scientists, and practitioners who came together for a webinar about the importance of IDS in salmon-bearing watersheds in British Columbia. I, the lead author, am a settler-descended academic who was hired by the Watershed Futures Initiative to work with the Tier-1 webinar contributors to draft outputs representing their words, experiences, and recommendations. I reflected critically on my positionality during the drafting of this manuscript to ensure that my experiences as a non-Indigenous researcher, and the biases that attest to the privileges I have been afforded as a white settler, did not greatly influence the descriptions of outputs from the webinar. I worked closely with the planning committee, coordination teams, and the webinar contributors to draft an internal report that summarized discussions from the webinar (not public), an executive summary (Supplementary Materials 2), an IDS toolkit (Supplementary Materials 3), and this manuscript. Importantly, however, any mistakes or misrepresentations in these materials are my own. It has been an honour and a privilege to work alongside the planning committee, coordination committee, and webinar contributors while drafting these outputs.

The webinar was organized by a planning committee, all of whom are members of First Nations in British Columbia: Axdii A Yee Stu Barnes (Gitksan; Webinar Chair; Chair of the Skeena Fisheries Commission); Gala“game Bob Chamberlin (Kwakwaka”wakw; Planning Committee Chair and Chairman of the First Nations Wild Salmon Alliance); Dr. Andrea Reid (Nisga'a; Assistant Professor and Principal Investigator for the Centre for Indigenous Fisheries, UBC); and Jennifer Walkus (Wuikinuxv; Councilor for the Wuikinuxv Tribal Council). The members of the coordination team worked to support the planning committee in organizing and hosting the webinar. The members of the coordination team are all researchers and practitioners of settler descent, including Sara Cannon (Postdoctoral Fellow, UBC and SFU); Emma Griggs (Salmon Watersheds Lab Manager, SFU); Julian Griggs (Dovetail Consulting Group); Jonathan Moore (Professor, SFU); and Nigel Sainsbury (Postdoctoral Researcher, SFU).

The webinar contributors are either Indigenous knowledge-holders or technical staff (who may be non-Indigenous but are employed by a First Nation). These contributors included Ryan Benson, M.Sc., Okanagan Nation Alliance; Danielle Burrows, Marine Stewardship Coordinator, Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council; Tatiana Degai, Itelmen people, Kamchatka, Russia, Assistant professor at the University of Victoria; Byron Charlie; David Dick, W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council, QENTOL, YEN/W̱SÁNEĆ Marine Guardians; Alexander T. Duncan, Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation; Kung Kayangas/Marlene Liddle (Haida Nation); Tara Marsden/Naxginkw (Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs and Hlimoo Sustainable Solutions); Maya Paul supporting the North Coast Cumulative Effects Program; Nathan Paul Prince, Traditional Land Use Coordinator, McLeod Lake Indian Band; Christine Scotnicki, Skeena Fisheries Commission; Kelly Speck, 'Namgis First Nation; Jamison Squakin (Okanagan Nation Alliance); Kasey M. Stirling, Nlaka'pamux Nation (Lower Nicola Indian Band member); Colton Van Der Minne, from Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation; Keith West, Fisheries and Wildlife Coordinator for the Takla Nation, and, Kii”iljuus (Barbara J. Wilson) MA, St'awaas XaaydaGa, Haida Gwaii. Of the 43 people who contributed to the workshop, 31 responded to our outreach, and 14 of these contributors opted to remain anonymous.

Webinar

The contributors were recruited through targeted invitations from the planning committee (SB, BC, AR, and JW), and the coordination team (SC, EG, JG, JM, and NS) recruited contributors through targeted invitations. The webinar was open to a Tier-1 audience (First Nations knowledge-holders and technical staff). All of the contributors to the workshop are co-authors of this manuscript.

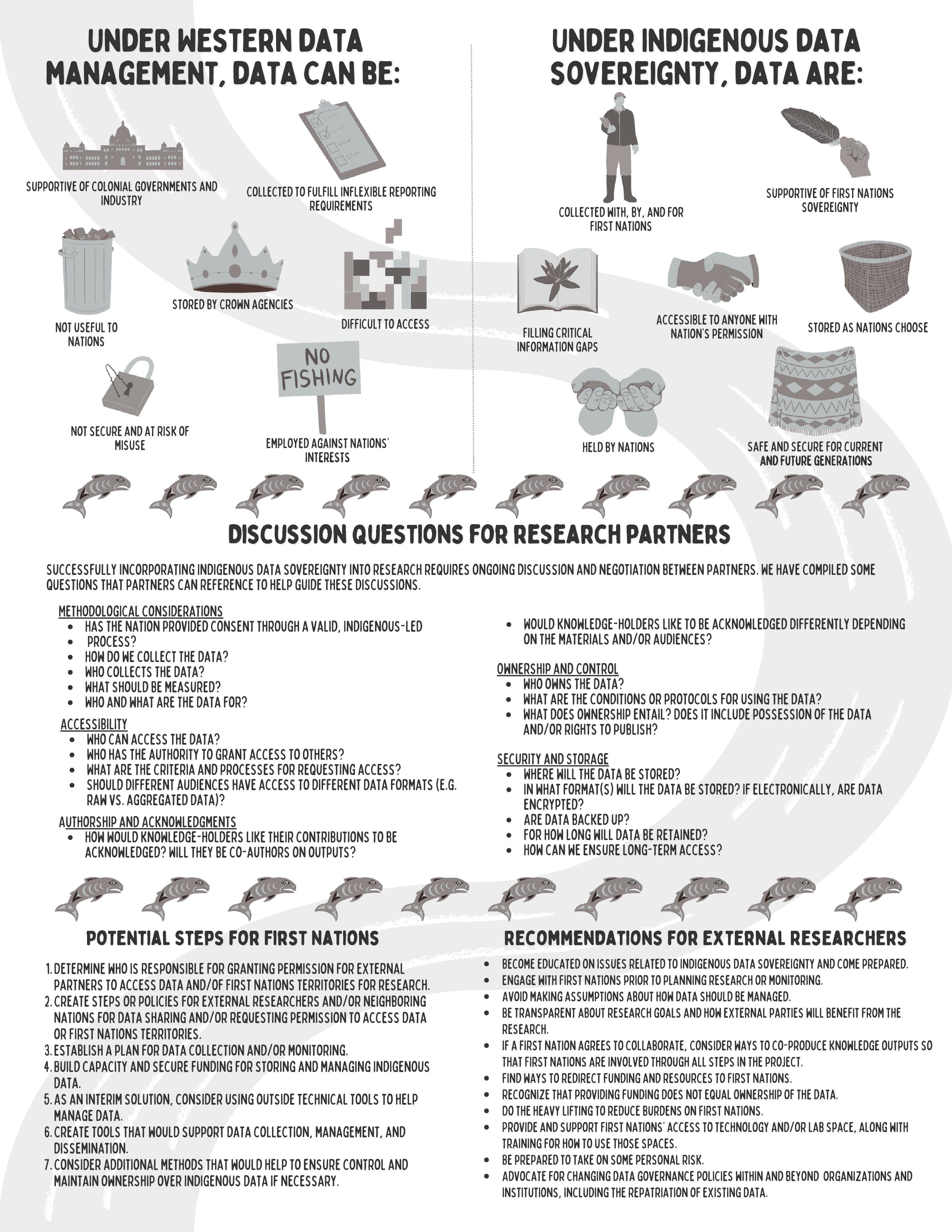

The online event included five presentations of case studies from: Dr. Andrea Reid, citizen of the Nisga'a Nation and Assistant Professor and PI for the Centre for Indigenous Fisheries at the University of British Columbia; Sean Young, Manager/Curator of Collections and Lab of Archaeology–Saahlinda Naay “Saving Things House” (Haida Gwaii Museum); Tara Marsden, Wilp Sustainability Director–Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs; Jennifer Walkus, Elected Councilor–Wuikinuxv Nation; Dr. Megan Adams, then a Postdoctoral Fellow with the Conservation Decisions Lab at the University of British Columbia; and Kelly Speck, Elected Councilor–‘Namgis Nation. The case studies are all publicly available online at https://www.watershedfuturesinitiative.com/indigenous-data-sovereignty. After the case studies, the 43 contributors, including the planning committee but not the coordination team, broke into small groups for discussions. Notetakers recorded the conversations, and Kelly Foxcroft Poirier recorded key themes graphically (Fig. 1). Contributors shared reflections from the presentations and case studies, described the current landscape of data sovereignty in British Columbia, discussed the challenges currently limiting IDS, and shared existing strategies and resources. They also brainstormed steps that First Nations can take as they work towards asserting sovereignty over their data and discussed recommendations for non-Indigenous researchers who are working on First Nations territories.

Fig. 1.

After the webinar, the coordination team invited the contributors to provide immediate feedback on the event via an online form (Supplementary Materials 4). The lead author (SC) then synthesized the notes from the notetakers into a summary report, along with draft potential steps for First Nations and recommendations for non-Indigenous researchers, that was based on the discussions from the workshop, using the notes, chat logs from Zoom®, and the graphic recording (Fig. 1). In addition, with guidance from the planning committee and the coordination team, the lead author requested all contributors to complete a Google form specifying how they would like to be acknowledged for their contributions to the workshop and the post-workshop materials and whether they would like to be named differently depending on the audience (Supplementary Materials 5). The coordination team finalized the report based on feedback and shared it with all of the webinar contributors, but did not distribute it publicly to respect the sensitive nature of some of the discussions. Some contributors opted to be named in the internal report but not in public-facing documents. If a workshop contributor did not respond after the lead author made several attempts to reach them (we did not receive a response from 12 of the webinar contributors), we included them among those who opted to be anonymous.

Next, the lead author (SC) invited the contributors to assist with drafting this manuscript, prepared a draft outline, and then organized those who expressed interest in drafting the manuscript into a writing team, which included representation from the workshop contributors, planning committee, and coordination team (AR, JG, JM, KS, MA, MP, NS, SC, TD, and TM). The writing team met twice over Zoom® throughout the process of drafting the manuscript to brainstorm, plan, draft, and discuss the text (first on 23 November 2022, and again on 2 March 2023). During the writing process, the writing team made a conscious effort to cite First Nations and Indigenous authors working within this space. The lead author received feedback and suggestions from the writing team at two steps in the process: first, after sharing a draft outline, and second, after sharing a full draft. On 30 March 2023, the writing team disseminated the draft among the remaining workshop contributors and requested further feedback and reviews by 1 May 2023. The lead author then incorporated that feedback into the final version of the manuscript, which she then shared with the contributors for final review and approval on 20 July 2023.

Results

The webinar contributors described the current data sovereignty landscape in British Columbia based on their experiences. While the results are specific to the contexts of the individuals contributing their knowledge through this workshop, all of whom were First Nations knowledge-holders and/or technical staff working for Nations in British Columbia, they may also have applicability for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Peoples across British Columbia and Canada, and Indigenous Peoples globally. The results described below are outputs from the workshop, although they may dovetail with and/or be supported by sources in the literature. We do not aim to present all the ideas we share as novel or to negate the work of others. Instead, we aim to share the experiences and suggestions raised by the workshop contributors, which provide guidance for First Nations in British Columbia and external researchers who are working to address cumulative effects and climate change in salmon-bearing ecosystems. To assist those who wish to engage more deeply with this body of literature, we have included citations where appropriate (also see the Indigenous data sovereignty toolkit in Supplementary Materials 3).

In general, contributors agreed that there have been some positive developments in relationships between non-Indigenous researchers and First Nations in British Columbia, but they also highlighted major challenges and an urgent need for continued improvement. For example, while non-Indigenous researchers are increasingly recognizing and valuing Indigenous knowledge, contributors noted that there is still a tendency for policymakers to dismiss it until Western scientific methods have proven what First Nations already know.

The contributors also highlighted an urgent need to transition away from current policies that require First Nations to track and report fish catches and share other environmental data without having a place in subsequent decision-making. First Nations communities are also often not funded for the work they do to care for and steward ecosystems and fish populations, but are increasingly being asked to provide these data to government agencies with little or no control over how those data are used. First Nations are also bogged down by reporting requirements for grants and other funding, which undermine IDS because the Nations spend time and resources collecting data required for outside agencies that may not necessarily support decision-making by the Nations themselves. First Nations communities would likely use different methods and/or collect different data if monitoring and data collection efforts were designed by the Nations themselves.

Potential steps for First Nations

During the workshop, contributors discussed steps that First Nations may be able to take to work towards asserting sovereignty over their data based on the experiences of the contributors. The steps presented here are not meant to be all-inclusive. The authors have worked together to slightly edit and add to the original steps while drafting this manuscript (see the workshop Executive Summary in Supplementary Materials 2 for the original steps and recommendations).

Step 1: Determine who is responsible for granting permission for external parties to access data and/or First Nations territories for research.

Contributors highlighted that this will require recognizing multiple authorities (e.g., hereditary and elected leaders) and reconciling governance systems.

Step 2: Create steps or policies for external researchers and/or neighbouring Nations for data sharing and/or requesting permission to access data or First Nations territories.

These policies will vary depending on the needs of each Nation but may include stipulations such as requiring research and/or data-sharing agreements in advance. Such agreements may include requirements that the Nation holds legal rights and ownership over all data collected on their territories and/or that the Nation must approve written materials making use of data before publication, i.e., what Schnarch calls “invoking a right to dissent” (2004). Several templates and guides are available to Indigenous Nations working to create these policies (please see the Data Sovereignty Toolkit in Supplementary Materials 3).

Step 3: Establish a plan for data collection and/or monitoring.

Most Nations are already collecting data, but these data are often not for their use and may go to external agencies or funders. What data would be useful for the Nation if they were not restricted by external requirements? Creating a priority list or plan, even if not immediately feasible, may help Nations to establish goals that would allow them to use their data to inform stewardship decisions. Again, Nations may be able to refer to existing templates and examples to assist with creating a plan (Supplementary Materials 3).

Step 4: Build capacity and secure funding for storing and managing Indigenous data.

First Nations in BC are making stewardship gains within their territories despite incredible odds (see the case studies from the workshop for examples). Increasing a Nation's technical capacity for storing, managing, and governing Indigenous data, and securing long-term funding to support these efforts, would further augment the existing benefits of Indigenous stewardship for salmon-bearing ecosystems. For capacity-building to be effective (and to avoid common pitfalls of capacity-building initiatives, e.g., West 2016), programs must be led by communities. Still, Nations may find support from external governments and researchers helpful. As Nations build technical capacity, they will be better able to collaborate with other Nations, and they may also learn from what other Nations have done and their successes. For example, some Nations have had success securing funding through unconventional sources, such as a local Public Utility District, while Nations working in watersheds that span the US/Canada border have received funding from transboundary watershed mitigation initiatives. Others have found allies in Crown government agencies who are willing to be creative in reallocating resources to First Nations. Extending land-based learning to younger generations can help to build and maintain capacity for data collection and the governance of Indigenous data and may also inspire First Nations youth to become further involved in these spaces.

Step 5: In the meantime, consider using outside technical tools to help manage data.

For Nations that are already collecting data for their initiatives, using third-party data storage sites or applications to manage data could help to bridge the gap until Nations can store and manage data in-house if this is their ultimate goal. Workshop contributors have used TrailMark Software or Community Knowledge Keeper, for example. In the United States, Mukurtu is an NSF-supported, free, open-source platform built with Indigenous communities to manage and share digital cultural heritage. However, Nations in Canada should familiarize themselves with the differences in privacy laws between the United States and Canada before uploading data to a US server (Levin and Nicholson 2005).

Step 6: Create tools that would support data collection, management, and dissemination.

Some Nations have already created these resources, for example, online data hubs and mobile apps. These Nations may be able to share ideas and experiences that could support other Nations. Alternatively, First Nations may want to consider pooling resources to create a neutral, centralized data hub where multiple Nations can store their data while retaining access, ownership, and control (e.g., Schnarch 2004; Johnson-Jennings et al. 2019). This approach also reduces research fatigue among community members by limiting repeated interview requests that may duplicate previous efforts and put undue pressure on community members, especially Elders (Schnarch 2004; Canada Research Coordinating Committee 2019; Brewer et al. 2023).

Step 7: Consider additional methods that would help to ensure control and maintain ownership over Indigenous data if necessary.

For example, labelling data using Traditional Knowledge labels (Local Contexts Hub 2015) may provide legal recourse if data are used inappropriately. Alternatively, retaining data in formats that are only accessible to people within the Nation may prevent its misuse (for example, recording interviews in Indigenous languages). By staying informed about evolving tools and approaches to data management, First Nations may be able to adapt their approaches to asserting sovereignty over data.

Recommendations for external researchers

During the webinar, contributors noted that external researchers, policymakers, and agencies can support IDS, both within their institutions and by supporting Nations themselves. To date, the peer-reviewed literature has mostly issued recommendations for policy changes that would facilitate IDS. While important, less has been said about how individual researchers can support First Nations who are working to assert sovereignty over data (but see Ignace et al. 2023).

The workshop contributors made several recommendations for external researchers working on First Nations territories in British Columbia. As noted above, many of these recommendations echo pre-existing suggestions in the literature, for example, to support ethical knowledge co-production (e.g., Castleden et al. 2010; Adams et al. 2014; Alexander et al. 2021; Cooke et al. 2021; Kitasoo/Xai'xais Stewardship Authority 2021; Smith 2021; Horsethief et al. 2022; Yua et al. 2022; Ignace et al. 2023).

Educate yourself on issues related to Indigenous data sovereignty and come prepared.

It is the responsibility of external researchers to learn about proper and respectful ways to approach and engage First Nations, and to share and discuss them with their colleagues (Ignace et al. 2023). External researchers must take time to read about IDS (Kukutai and Taylor 2016; Walter et al. 2021), familiarize themselves with existing tools for supporting IDS in BC and Canada, such as OCAP® (FNIGC 2014) or the CARE principles (Carroll et al. 2021; Jennings et al. 2023), review guidelines and frameworks that support engagement with First Nations (e.g., Kitasoo/Xai'xais Stewardship Authority 2021; Horsethief et al. 2022), and do some self-reflection to ensure that they have good intentions in reaching out to First Nations. Non-Indigenous researchers should understand that First Nations have reasons for being wary of external researchers and have some preliminary understanding of these reasons so that they can avoid making the same mistakes.

In addition, external researchers can do preliminary research on the Nation's data-sharing policies and provide a draft data-sharing agreement in advance. Many Nations already have data-sharing agreements, while others do not. However, external researchers must realize that many Nations are struggling to manage and track an influx of requests on their time, and even if those requests are meant to support First Nations communities, they still require significant time and effort for Nations to process and respond. Doing preliminary research on the Nation's policies and providing a template agreement in advance can reduce burdens on First Nations collaborators. Still, external researchers must defer to the Nation for finalizing these agreements and recognize that they will likely require ongoing negotiation and consultation.

Engage with First Nations before planning research or monitoring.

Nations should have the option to collaborate with outside researchers to ensure that the knowledge produced through the research is useful to them. This requires negotiation and consultation that occurs well in advance of the research project. Different projects and approaches to collecting data may require different policies to guide how the data are used, shared, and protected. Having early conversations with communities can help them to develop these policies and to build capacity for dealing with questions about managing data in the future. In addition, external researchers should take the time to learn about the Nation's current research priorities and how they relate to the proposed research. Knowing this in advance may help external researchers consider how their skills and expertise may contribute to priorities identified by the Nation. In addition, approaching Nations respectfully in advance helps to build trust between researchers and community members, and this remains an important requirement for collaborations as First Nations find that Indigenous knowledge remains undervalued and that external researchers or policymakers do not always have the best interests of the Nation in mind.

Avoid making assumptions about how data should be managed.

Nations have diverse needs, interests, and priorities, and approaches to managing data must be made by each Nation. Some Nations may opt to make data publicly available, while others may choose to release data on a case-by-case basis. As noted above, different projects and approaches may require distinct approaches to data management, even within the same Nation. Implementing IDS requires that external researchers defer to the Nations for all decisions on how data are collected, stored, accessed, and shared on a project-specific basis.

Be transparent about the research goals and how external parties will benefit from the research.

Researcher transparency is an integral part of building trusting relationships with First Nations. Building trust takes time and, in some cases, may not be feasible in the short or medium term because of the legacy of past experiences. For example, workshop contributors were not convinced that they could build trust with DFO because the agency has continued to withhold data protecting industry at the expense of First Nations. This lack of transparency has only added to the lack of trust between many First Nations and DFOs. Therefore, transparency is essential, and First Nations must have access to and control over data, including when and how it is shared publicly.

Identify ways to co-create knowledge outputs so that First Nations are involved through all steps in the process (if they agree to participate).

Currently, Nations are collecting data to meet funding requirements and/or to provide information to external parties, but without having the power to engage in decision-making or to control how those data are used. Knowledge co-creation is one way that workshop contributors thought external researchers could stop perpetuating this pattern. For example, when knowledge is truly co-created, the research is helpful for Nations, and undergoing data collection together may also build capacity for community members who want to collect and manage data in the future. Another possibility is for collaborators to appoint an advisory committee that includes First Nations community members who are on the research team alongside external researchers. In this way, community members can guide discussions about what can be done and what needs to be done, and they can properly guide the research so that it meets the needs of their communities while following respectful and proper protocols.

Find ways to redirect funding and resources to First Nations.

Funding and capacity-building were two of the key challenges noted during the webinar that face First Nations as they work to assert sovereignty over their data. In particular, Nations highlight a need for reliable, long-term funding rather than short-term funding, as is typical with academic and/or government support. Securing long-term and stable funding support may be outside the ability of an individual researcher, but it is something to be aware of in case there are opportunities for long-term research partnerships that may support a Nation. Contributors also shared additional ways that external researchers can secure support for First Nations partners. A part of this is being willing to think outside the box. Contributors shared that they have worked with allies in universities or government agencies who are willing to get creative to redirect resources to the Nations. In addition, non-Indigenous researchers should pay First Nations community members who are supporting the research or project and ensure that they are paid at the same rate as external researchers and consultants. Researchers commonly hire interns or research assistants to support data collection and other tasks. Rather than hiring from outside the Nation, work with communities to hire from within. This also supports capacity-building as community members gain experience with fieldwork and may find ways that they can use Western scientific methods to support data collection for their uses in the future. Given the tendency to undervalue Indigenous knowledge in research and policy circles, First Nations community members are often paid at lower rates than external “experts”. Some Nations are instituting policies that require wage parity; people who are members of the Nation must be paid at the same rate as employees from DFO or other Crown agencies who do the same or similar work, and Elders, who are the holders of Indigenous knowledge, must be paid at the same rate as external consultants for their time.

Recognize that providing funding does not equal ownership of the data.

Discussion groups highlighted that there is a tendency for granting agencies and/or external researchers to assume that by funding data collection, the data belongs to them. This undermines IDS, and researchers can take steps, for example, through data sharing agreements, to ensure that First Nations retain ownership and control over the data as they see fit. In some cases, external researchers may be restricted via internal university or agency policies. In these cases, they should be transparent with First Nations while advocating to change these policies within their organizations.

Do the heavy lifting to reduce burdens on First Nations.

When making requests to First Nations research partners, researchers can ask themselves whether they can address any part of the request on their own. If yes, external researchers should be prepared to take on that labour whenever possible. Again, First Nations are dealing with an influx of requests for their time, and it is important to remember this when asking partners for information or to complete tasks. This way, external researchers can avoid unnecessary burdens on their First Nations partners. Importantly, researchers should not expect any benefits or recognition in return for doing the heavy lifting. Instead, they should recognize that doing the work to reduce burdens on First Nations is one way to account for differences in power between First Nations and external researchers or practitioners.

Provide and support First Nations’ access to technology and/or lab space, along with training for how to use those spaces.

Some Nations have had to find their own ways to process data or access resources because they do not have access to laboratory spaces. Researchers who do have access to those resources can help process data and/or find ways to share lab space and equipment with First Nations so that they have the tools necessary to conduct their research. They can also provide training opportunities to help First Nations build capacity for using Western scientific methodologies.

Be prepared to take on some personal risk.

It has been the experience of some members of the coordination team that academic institutions are not equipped to support formal agreements between academic researchers and Indigenous communities. Rather than supporting and recognizing research or data-sharing agreements as a way to protect Indigenous partners from risk in the context of extreme differences in power, an institution's legal representatives may seek to protect the institution at all costs, for example, by editing potential agreements for the protection of the academic institution to the extent that they become untenable. Thus, academic researchers may need to take on personal risk when institutions refuse to guarantee the terms of a data-sharing agreement. This underlines the need for systemic and institutional changes in agreements with Indigenous Peoples and in data management.

Advocate for changing data governance policies within and beyond organizations or institutions, including the repatriation of existing data.

External researchers attempting to work with Nations to support their assertion of IDS may run into challenges with associated granting or publishing organizations. Funding agencies sometimes require that they maintain ownership of the data after a project is completed, for example, which gives them control over how the data are used, potentially at the expense of Nations. Some journals have also instituted open data policies, requiring that data be posted to an online data repository. While some Nations may not object to sharing data publicly, the choice must be the Nation's, and they should retain ownership over their data so that they can choose to remove or change access requirements in the future. By working within their institutions, pushing back against universal data-sharing requirements, or boycotting journals that are unwilling to be flexible in their data policies, external researchers can work to change norms in environmental research that are at odds with IDS. It is the experience of some of the organizing team that some journals, despite having open data mandates, will respect the need to not share data due to IDS; however, others on the organizing team have experienced pushback from journal editors in this same situation.