4.5. Quechua—Sumak Kausay

In the Andes, according to

Argumedo (2022), the

Sumak Kausay (“buen vivir” in Spanish), which can be translated as “harmonious existence”, is a socio-political paradigm rooted in the Quechua people’s cosmovision. It describes a holistic vision that encompasses diverse but complementary aspects of well-being. He also shared that

Sumaq Kausay is achieved only when we create balance between the realms of human activity, the natural environment, and the sacred. In addition, he stated that balance and harmony require reciprocity and respect for differences (duality and complementarity). For him, in opposition to the “market-is-king model of capitalism”,

Sumak Kausay expresses, in the day-to-day experiences of Indigenous Peoples, a way of doing things that is community-centric, ecologically balanced, and culturally sensitive. The interrelation that exists between the planet health and the life (beings) is well illustrated in the etymology of

Sumaq Kausay, where

Sumak refers to the ideal and beautiful fulfillment of the planet; and

Kawsay means “life”, a life with dignity, plenitude, balance, and harmony (

Argumedo 2022).

4.10. North Sámi—Birgejupmi

Birgejupmi is a North Sámi term for “life sustenance, livelihood, survival capacity, and the way people (individuals and communities) maintain themselves in a certain area with its respective resources, which exist or can be found in the natural and social environment”. It requires know-how skills, resourcefulness, reflexivity, professional, and social competence. It ties together people, communities, humans and non-human beings, landscape and natural environment, the ecosystem, healthy social and spiritual development, and identity.”

Irja Seurujärvi-Kari shared that “[t]he term birgejupmi derives from the verb

birget—to maintain life, which is used widely in everyday talk.

Birgejupmi means life skills and collectively cumulated knowledge that a society and people need to be able to master their life in a holistic way. Therefore, children have been traditionally raised to be

iešbirgejeaddji—independent, self-supporting, able to deal with unexpected situations and solve challenges, both individually and together with others, in a given environment with its resources. Good life maintenance traditionally means good reciprocal relationships between human and non-human beings and the environment in terms of sustainability. Reciprocity, in this connection, means the maintenance of healthy societies and healthy environment with its diversity and resources” (

Porsanger and Guttorm 2011, pages 17−21).

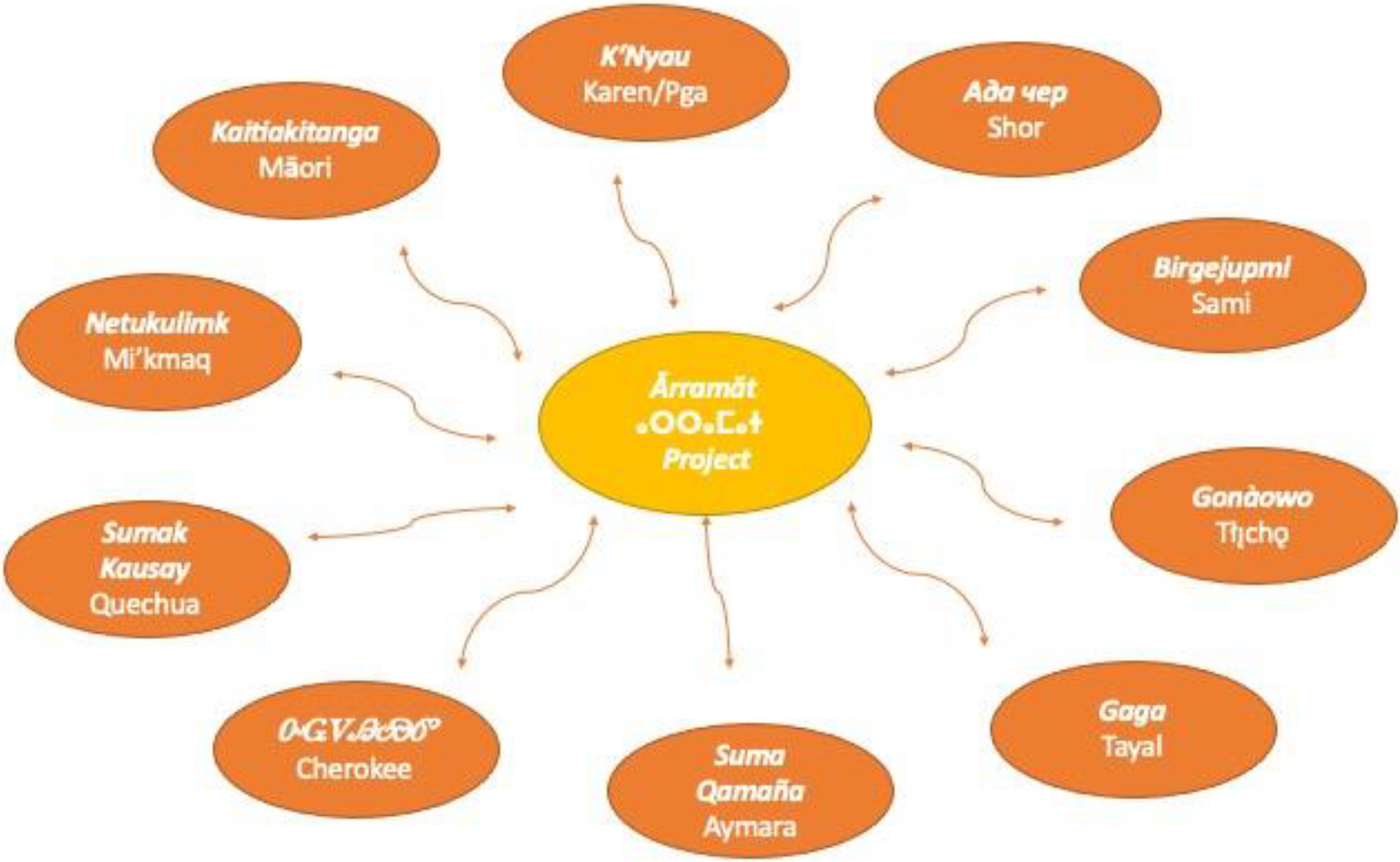

4.12. Tuareg—Ărramăt

It emerges from all these Indigenous concepts that there is an inextricable link between human beings and Mother Earth. She has laws and teachings that she passes onto us, and we need to respect them to keep the balance we all need to continue to exist. In the second part of this chapter, we will share with you the path to indigenize our research project application through the utilization of an Indigenous word:

Ărramăt. To adopt a concept that reflects all the dimensions of our project, in particular the holistic approach, the ethic for our working relationships among us and the Indigenous territories, we initiated virtual talks and discussions with linguists, Elders, women, and youth from the Kel Tamasheq (

Solimane et al. 2021).

Several words were suggested, including

Essoufou, which is a concept that is used to assess health and well-being both for beings and non-beings but more for comparison. For example, when MW asks someone who is sick about her/his health, if he/she feels better, he/she will respond by saying: “

essofegh imanin acheli dagh”, which I translated from Tamasheq to English as: I feel/or prefer myself better today. However, all the people interviewed agreed on the concept of

Ărramăt, which is defined in the dictionary as being a magical effectiveness, the good health, the physical strength, according to

Prasse et al. (1998). For the interviewees of this project, this concept means both a state of balance among

ihenzuzagh (environment, habitat),

irezedjen (animals),

deg adam (human beings), and a state of (full) health and well-being of the last.

The meaning of an Ărramăt state appears through several elements in the traditional livelihood of Kel Tamasheq and in their worldview. For example, for these People, the state of Ărramăt is shared by environment, animals, and humans. We say that some ihenzuzagh have the Ărramăt or contain the Ărramăt, which means that they are free of any echar (wrong) or elaroret (something that disturbs). Also, it means that humans can live in harmony among themselves as well as with other beings and nature, as this land gives enough resources (water, grass, beautiful landscape) to feed people, their livestock, and other beings, consequently maintaining their physical, mental, and spiritual health and well-being.

However, the

Ărramăt is not guaranteed; it is not a static state. For example,

ihezenzuzagh (environment, habitat) can lose it if they are overused because they are inhabited in a disrespectful way, or by a high number of animals or humans, or for a long period. This is precisely what has justified the transhumance that is practiced by the Kel Tamasheq, not only to find new grazing pastures, but also to preserve the

timchar, which is the space from which the camp will move. No one should exhaust or degrade the balance and respect that guide the relationships within an ecosystem. Everyone should leave the land in a state from which it can regenerate during the next season (

Mahmoud 1992). Also, in lands of high pastoralism where nomadism during the rainy season has been abandoned, where pastures have been overexploited, this has led to irreversible desertification of the land. On the other hand, in the low pasture areas where the exploitation of pastures has been alternated, the vegetation has not been degraded (

Barral 1974). So, pastoralism as a mode of environmental management is beneficial for the well-being of pastures, animals, and humans. This way of life contributes to

Ărramăt.

In addition, nomadic pastoralists follow specific indicators of decrease in Earth’s wealth that can guide the choice of

ihenzuzagh, as well as the choice of the moment and the place to which it is necessary to move. These indicators can be observed at different levels:

a.

From the environment:

Tichikwalene (whirlwind) and

Eylal (mirages) in hot season, for the Kel Tamasheq who still practice nomadism, one of these two events/signs suggests the moment to move closer to water points. There is also

tidjarakene (clouds), which announces

akessa or raining season (wintering).

Alemoz (plants of the Brassicaceae family) and

Takana (cram cram or

Cenchrus biflorus) announce the post-wintering season. It is the period when the Kel Tamasheq move in search of fresh grass for the well-being of animals.

Amaldja (

Acacia nilotica fruits) announces

tadjrest or cold season, where movements happen toward places where there is salt (salt lick). There is also the water which becomes cloudy,

adelogh, which is a sign of imbalance, and which indicates that it is time to leave these

timshar, because without water there is no life for animals nor for humans and there is a disbalance in nature. The Kel Tamasheq have a proverb that relates this central place of water people:

aman iman, “water is life” or is “the soul” (

Ansary et al. 2021). This proverb suggests that besides physical dependency, these people have also a spiritual relationship with water.

b.

The animals: the sharp decrease of milk, the polyphagy, and the decrease of libido for the herd are signs of iba en Ărramăt, or “lack” of Ărramăt, which translates as not reaching a state of health and well-being.

c.

The humans: tebehewt en elem which is skin’s dull appearance. The skin loses its radiance, its natural tone, and becomes dry and loses its brightness. There is also a state of fatigue.

These indicators are occasionals and disappear when people change timshar. However, in this case of climatic crisis, such as drought, it is unfortunately a state of generalized faintness and for all ihenzuzagh in a given region, thus having impacts on other elements of nature. In this case, movements are unusual, uncontrolled, and can extend to territories that are not the ones where Kel Tamasheq are used to nomadize for grazing their herds. This can also explain several inter-communal conflicts between pastoralists nomads and sedentary farmers.

Besides these observable indicators, there are also what we call teneyast or “prospection”. These indicators are collected either by sending a member of the camp to the place where the people are considering moving by asking people who live there when meeting them at the market, during a baptism, a wedding, or for a cup of tea. Some examples of questions that are usually asked for that purpose are: “Are the animals good?”, “Are the animals mating?”, and “Do cows have enough milk?”.