Introduction

Few biomedical grant applications are successful (

Guthrie et al. 2018a). When an application is rejected, applicants are typically encouraged to revise and resubmit their applications (

Lauer 2016;

Crow 2020), an expensive and time-consuming task (

Herbert et al. 2013;

Gross and Bergstrom 2019). Given the low chances of success, researchers may question whether it is worth resubmitting the grant application (

Crow 2020). Here, we describe the outcomes of resubmitted applications to the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Open Grants competitions.

In the U.S., resubmitted applications to the National Institute of Health (NIH) programs are more successful than new applications (

Lauer 2016;

Nakamura et al. 2021), though success rates remain modest (

Lauer 2016). Researchers require clear, actionable information to help them decide whether to resubmit a rejected grant application (

Derrick et al. 2023), without which they may face multiple rejections from the same competition (

von Hippel and von Hippel 2015). For NIH competitions, quantitative results (e.g., scores, ranking) from the peer review of the rejected application are related to whether someone decides to resubmit (

Boyington et al. 2016;

Hunter et al. 2024) and the success of the resubmission (

Lauer 2017). There are few data for other programs and countries, and it is not clear whether data from the NIH can be generalized to other funding systems (

Lasinsky et al. 2024). Other factors such as applicants’ sex/gender, their previous funding success, and reviewer and review panel characteristics may also be related to whether a grant is funded (

Guthrie et al. 2018a). Some of these factors may be related to how CIHR project grants are assessed (

Tamblyn et al. 2018). However, to date, factors related to the success of resubmissions to the CIHR Project Grant Competition have not been explored.

Biomedical science and its benefits to society depend on successful applications for public research funding (

Yin et al. 2022). Substantial resources are wasted on repeated unsuccessful applications (

Gross and Bergstrom 2019). To help researchers decide whether to resubmit their rejected grant application, this exploratory study analyzed over a decade of resubmission data from the CIHR Open Operating Grant and Project Grant competitions. The aims were to describe the data to (i) identify success rates of resubmitted CIHR operating and project grant applications and (ii) highlight which factors were the most important for resubmission success.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of observational data collected by CIHR between 2010 and 2022. When appropriate, the methods are reported in accordance with the relevant requirements of the Minimum Information about Clinical Artificial Intelligence Modeling (MI-CLAIM) checklist (

Norgeot et al. 2020). A completed checklist is included in the Supplementary Material (Table S1). The Behavioural Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia approved the study (H23-00719; 31 March 2023).

Context

The CIHR Open Grants competition—which currently accounts for approximately $750 million of CIHR’s $1.3 billion annual funding budget—is open to independent researchers at any career stage who seek funding to support their proposed fundamental or applied health-related research. The Open Grants competition comprises both the Open Operating Grants and the Project Grant competitions, data from which were extracted for 2010–2015 and 2017–2022, respectively. Each Peer Review Committee ranks the applications it considers in a competition in an approach intended to account for varying ways that grant applications are scored by approximately 60 different Peer Review Committees in each competition. The application rank, and not its score, dictates funding decisions.

How CIHR handles resubmitted grant applications

Applicants may submit a previously unfunded application in a subsequent Open Grant competition round. There is currently no limit on the number of times an unsuccessful application can be resubmitted. Although applicants can respond to the previous application’s feedback, CIHR instructs peer review committee members to consider a resubmitted grant application as a new application (i.e., relative to all others in the current competition) and states that “…addressing previous reviews does NOT guarantee that the application will be better positioned to be funded….” A resubmitted application can be reviewed by a different peer review committee than the previously unfunded application and committees do not have access to the previous version of the resubmitted application, though members are asked to read and evaluate the applicant’s response to the previous review (

Canadian Institutes of Health Research 2016).

Study design and dataset

Applications submitted to the Open Grant competition were surveyed to identify those that were new applications, unsuccessful, and followed by resubmission to the same program by the same Principal Investigator (PI). Data were extracted from 50 138 applications to the CIHR Open Operating Grant and Project Grant competitions. Applications submitted to the 2016 Open Grant competitions were not included because different reviewing and adjudication methodologies were used at that time. For the random forest model (see Data analysis, below), a randomly selected subset (20% of the data) was held back for model testing (“Test dataset”), and the remaining 80% of data were used for model training (“Training dataset”).

Consent

Every researcher who submitted an application to the CIHR Project Grant Competition consented to the CIHR Policy on “Use of Personal Information”. CIHR maintained a record of all grant applications and the assessment records (including information from the Canadian Common Curriculum Vitae) of researchers who applied for funding. Our study included an objective of quality assurance and quality improvement of CIHR’s programs and thus fell under Article 2.5 of Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans.

Data analysis

We performed an exploratory analysis (

Tukey 1980) to (1) describe the proportion of new and resubmitted applications that were funded and (2) identify the importance of variables related to the outcome (funded/not funded) of resubmissions using a random forest model. The primary outcome was the proportion of successful resubmitted and new grant applications (%). Analysis was performed using the R programming language (version 4.3.1) and the

randomforest R package (

Liaw and Wiener 2002;

R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2023)

Data wrangling

The PI’s sex was hypothesized to be a significant explanatory variable (

Guthrie et al. 2018a). Applications where the PI had not self-identified their sex (

n = 37) were excluded. Applications were identified as resubmissions if they included a response to a previous review and could be paired with a preceding unfunded new application submitted by the same PI. The unit of analysis was application pairs. Resubmissions that could not be paired with a previously unfunded application (

n = 9310) were excluded from analyses.

Variable importance

We used a 10-fold cross-validated random forest model to identify the importance of candidate variables related to the outcome of resubmissions. A random forest is an ensemble learning model that combines multiple decision trees, and provides methods to describe the relative importance of explanatory variables, such as the Gini variable importance measure (

Breiman 2001;

Saarela and Jauhiainen 2021). We used a random forest model because of its ability to derive ranked lists of variables important to the outcome and handle nonlinear relationships and interactions between variables and outcomes. We used partial dependence plots to visualize the marginal effect of important variables on the probability of funding. Plots showing the results of hyperparameter tuning are shown in the Supplementary Material, Fig. S1. The parameter values selected maximized model sensitivity (true positive classification) and specificity (true negative classification) (mtry = 3, nodesize = 1, ntrees = 1000).

The relative importance of each explanatory variable was calculated using the mean decrease of Gini impurity (a method for assessing how effectively the explanatory variables split the data based on the primary outcome) aggregated across the folds. While the primary aim of our study was description, not prediction, for completeness, we also measured the prediction accuracy of the model using the unseen (Test) dataset; these results are shown in the supplementary material.

Explanatory variables

The secondary outcome was the Gini importance of each of the candidate explanatory variables related to resubmission success. Candidate explanatory variables were selected from the factors related to grant resubmissions identified in our recent scoping review (

Lasinsky et al. 2024) and other work highlighting possible biases in grant peer review selection (

Tamblyn et al. 2018;

Guthrie et al. 2018b,

2019) and from factors related to resubmissions in other funding competitions (

Boyington et al. 2016). Two variable categories were identified: (i) characteristics of the applicant (the named PI) and (ii) factors related to peer review. Variables included in the final model were: self-identified applicant sex (male, female), previous total CIHR funding awarded in CAD$M to all projects where the PI was a named team member (“PI $ Funding”), the number of CIHR-funded projects that contributed to “PI $ Funding” at the time of application (“PI # grants”), whether the applicant had chosen English or French as the application language, whether the resubmitted application was reviewed by the same peer review committee (true, false), whether the resubmitted application was reviewed by one or more of the same peer reviewers within the peer review committee (true, false), and the score (“Previous Score, out of 5”) and ranking (“Previous % Rank”) of the preceding application.

Discussion

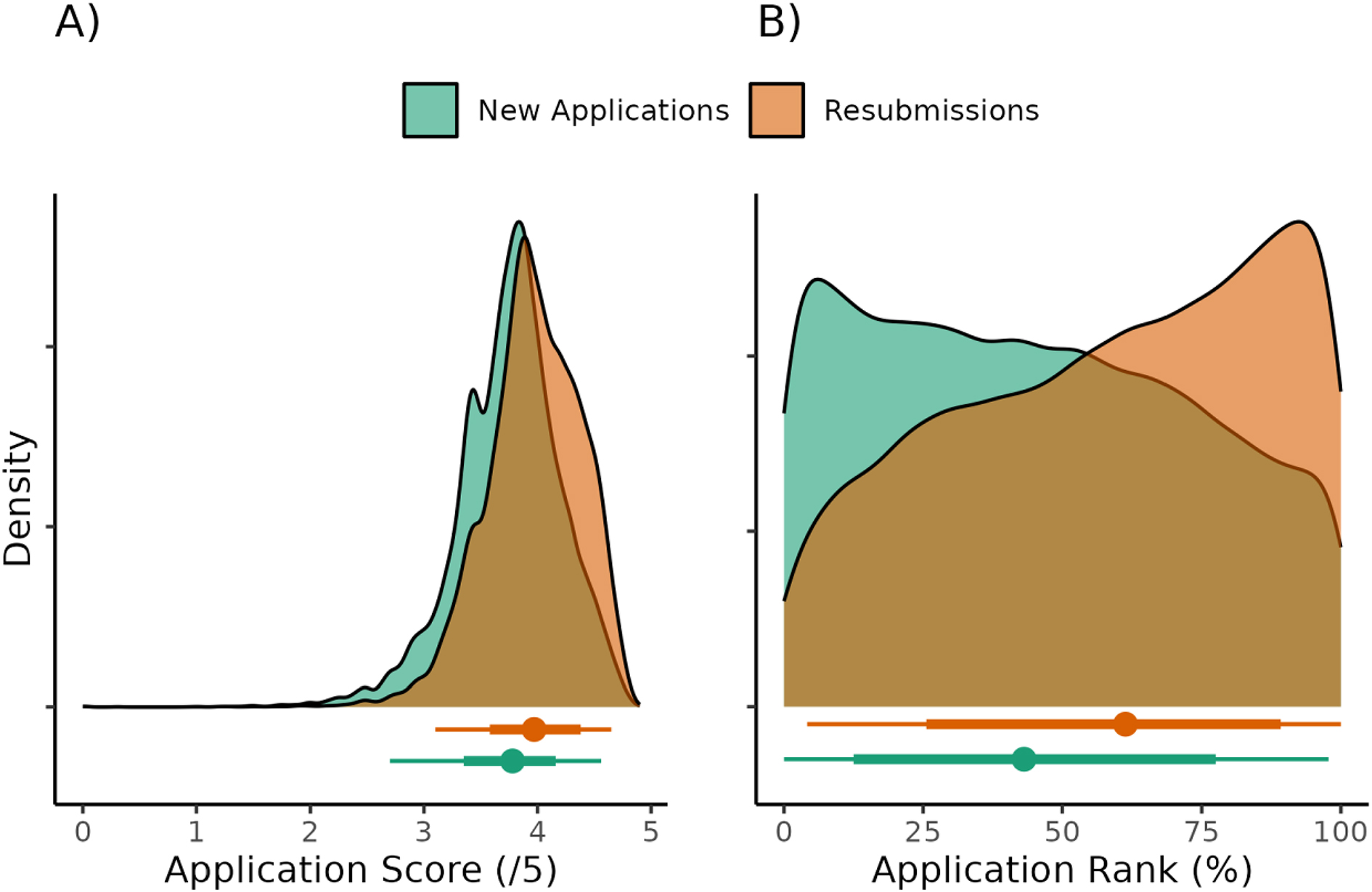

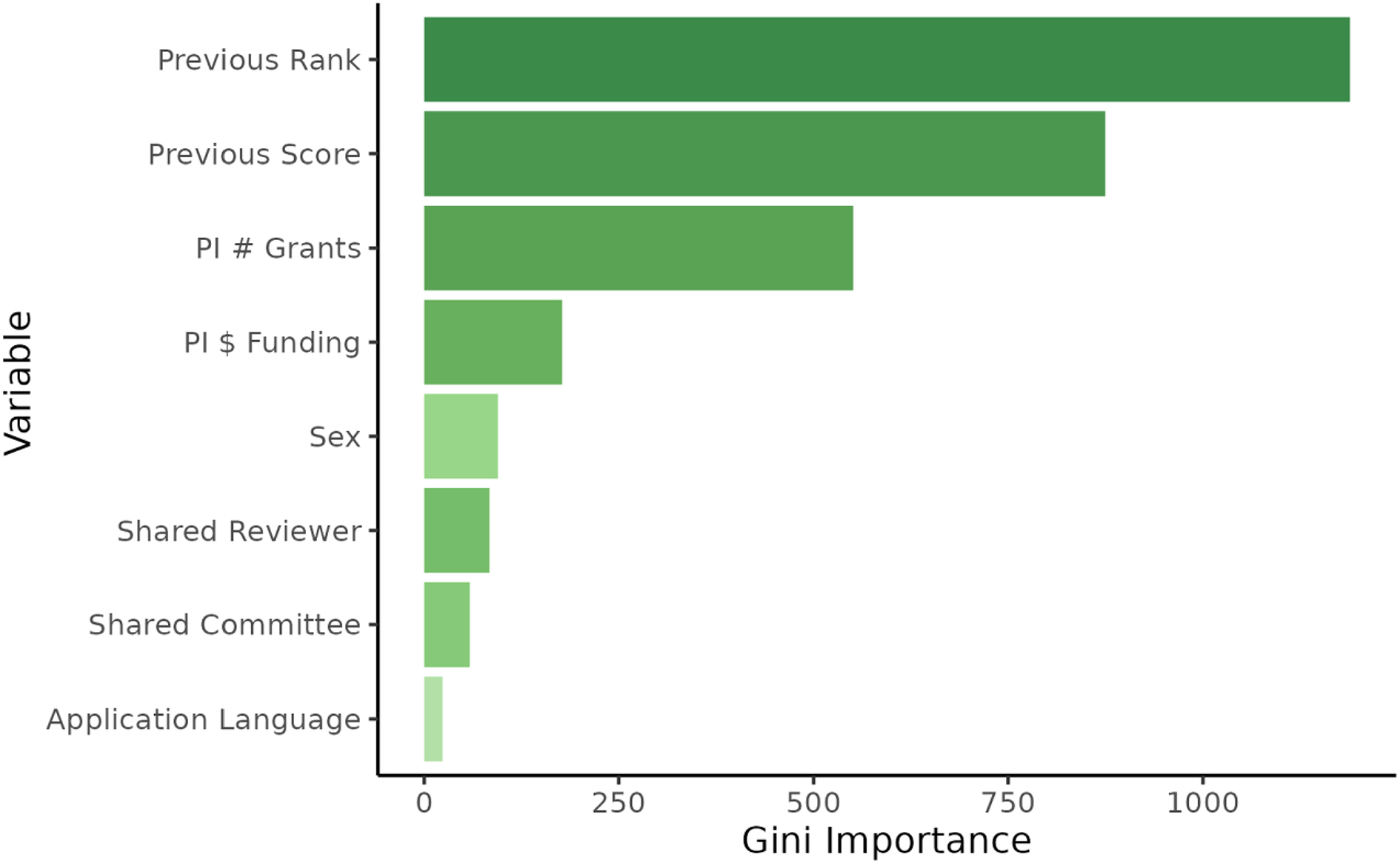

Our results add to the literature on health research grant funding and peer review in two ways. First, we show that resubmitted applications to the CIHR Project Grant Competition were funded more often and ranked and scored higher than new applications. Second, we show that the peer review ranking of the previous application was the most important variable related to whether a resubmitted application was funded. Applicant sex, application language, and peer review continuity were the least important. Applicants who are considering resubmitting an unsuccessful application should feel encouraged by improved peer review outcomes for resubmissions and may wish to consider the ranking of their previous application when deciding whether to resubmit a grant application to the CIHR Project Grant Competition.

Matching data from the U.S. NIH (

Lauer 2016;

Nakamura et al. 2021), here we found a greater proportion of resubmitted applications were funded than new applications, and on average, resubmissions received a higher rank and score. We suggest three potential drivers of improved outcomes: First, it is possible that those who chose to resubmit were those who could adequately respond to the peer review feedback. Second, because CIHR treats resubmissions as new applications and instructs reviewers to compare them only to their present cohort, those who resubmit may be those whose application was more likely to be funded anyway (i.e., the application may be good but not quite good enough compared to the previous cohort it was initially judged against). Finally, a proportion of applicants whose applications received unfavourable reviews may choose not to resubmit, increasing the proportion of resubmissions that are likely to be funded.

Unlike journal peer review, providing applicant feedback is a lower priority of grant peer review committees (

Guthrie et al. 2018a). However, applicants are recommended to, and do, use feedback to help with grant resubmission (

Derrick et al. 2023;

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases 2023;

Hunter et al. 2024). High-quality feedback helps researchers decide whether to submit their application (

Derrick et al. 2023) low-quality feedback can confuse applicants (

Gallo et al. 2021) and may lead to multiple unsuccessful resubmissions (

von Hippel and von Hippel 2015). CIHR has clear guidance for reviewers to promote high-quality reviews (

Canadian Institutes of Health Research 2018) and evaluates the performance of peer reviewers (

Ardern et al. 2023), which may have contributed to the improved success of resubmissions seen here. Unlike journal peer review (

Superchi et al. 2019), there has been little scientific evaluation of the impact of grant peer review feedback quality (see also

Derrick et al. 2023), perhaps due to the continuing opacity of many grant peer review systems despite increasing calls for transparency (

Horbach et al. 2022;

Bouter 2023;

Schweiger 2023). Given the substantial time, effort, and financial costs to applicants and society of grant applications, revisions and resubmissions (

Herbert et al. 2013;

von Hippel and von Hippel 2015;

Schweiger 2023), more research is warranted on how reviewer feedback impacts the volume, quality, and success of subsequent grant applications.

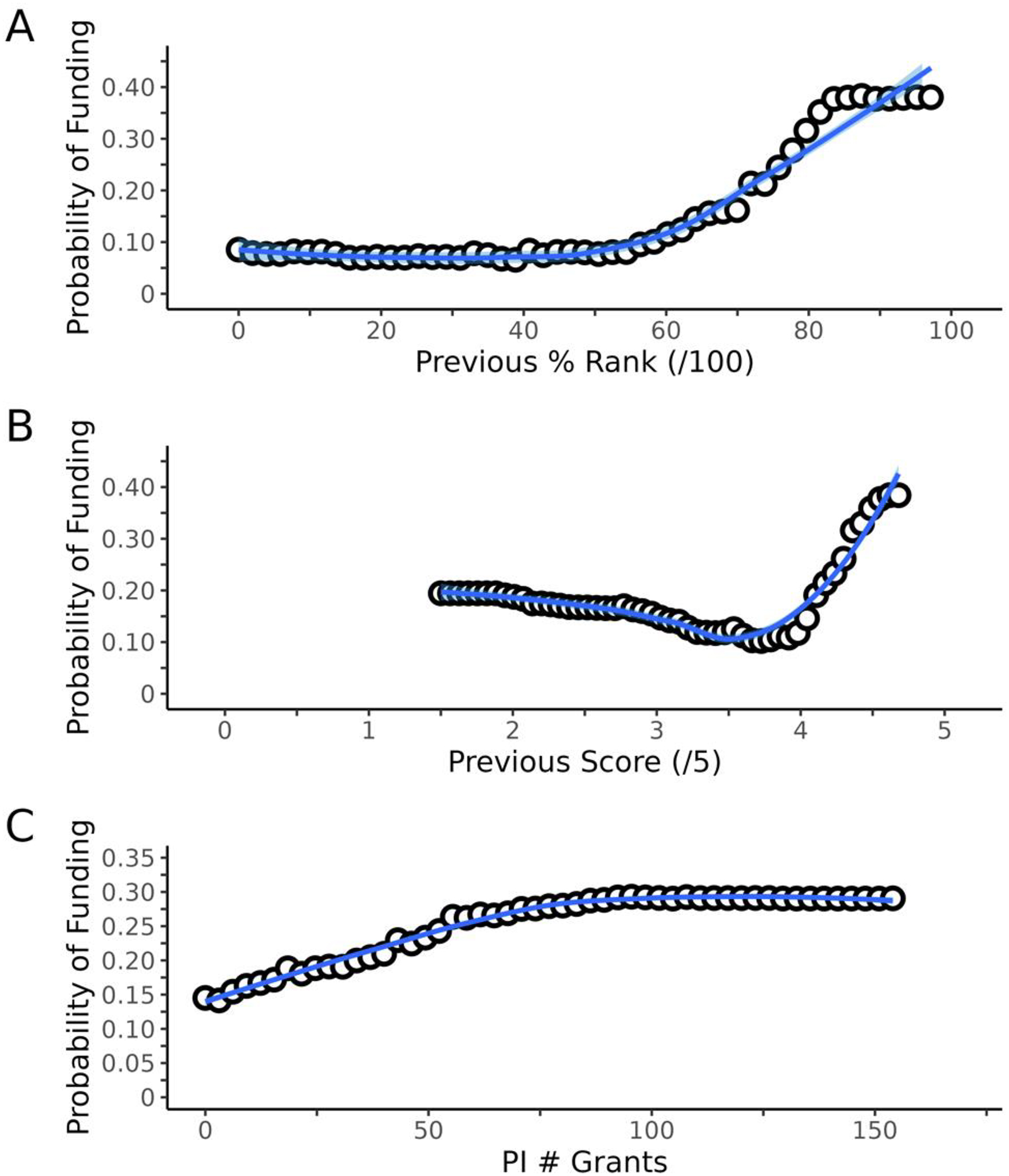

The most important factor related to the outcome of a resubmitted CIHR Open Grant competition was the rank given to the previous application. While many applicants may have assumed that the result of the previous peer review was related to the binary outcome of a resubmitted application, this is direct evidence of the relationship. The importance of rank compared to score may surprise some applicants, especially given the relevance of previous scores for resubmissions in other funding systems (

Boyington et al. 2016;

Lauer 2017;

Hunter et al. 2024). For some applicants, knowledge of the relationship between the previous applications’ rank and resubmission success may help them make an informed decision about whether to resubmit a grant application. In particular, the relationships between previous rank and score, and the probability of funding success, shown in

Fig. 4, may be informative. A cautious interpretation of these figures suggests a higher probability of funding success for applications that were previously ranked 60% or above and with scores of 4.0 or above. There was a slightly higher probability of funding for applications with very low previous scores (∼2) than those with previous scores of ∼ 3.5. Lower-scored grants were rarely resubmitted (see Fig. S1 and

Table 1), possibly because they were “streamlined” (not discussed) by peer reviewers. Unmeasured factors may have increased the probability of funding for these outliers, and we caution against extrapolating the data. Future research is warranted to understand the motivations and approach of applicants who successfully resubmit very low-scored grants to help guide applicants.

The number of CIHR-funded projects the PI had been awarded was the third most important factor, after previous application rank and score. This result could be interpreted in at least two ways. The first is that grant writing is a skill (

Weber-Main et al. 2020), and one might assume that researchers may become more skilled in responding to reviewer comments with experience, especially with successful grants (

Guyer et al. 2021). An alternative interpretation is that the result reflects the “Matthew effect” in grant funding wherein previous success begets future success. A small group of previously successful researchers, rewarded more often on that basis, would threaten the assumed meritocracy of research funding systems (

Bol et al. 2018). Our observational data do not allow us to disentangle these explanations, though we speculate that both may be true. We found that applicant sex was among the least important factors related to resubmission outcome. However, we cannot conclude that sex bias does not affect the outcome of resubmission, and this topic remains an important avenue for future research (

Ceci et al. 2023;

Schmaling and Gallo 2023).

Recent innovations in grant peer review including “funding lotteries” (

Heyard et al. 2022) and double-blind peer review processes (

Qussini et al. 2023) have been designed to reduce inherent bias in grant selection and peer review. Future research should examine whether the relationship between past success and the outcome of resubmissions still exists in applications to competitions that use these mechanisms designed to reduce bias.

This was an exploratory cross-sectional study, which precludes causal inferences about the relationship between the applicant and peer review characteristics and grant resubmission success. We echo previous calls for further examination of grant peer review systems, including randomized controlled trials, to examine the causal factors that influence funding success (

Grant 2017;

Severin and Egger 2021;

Horbach et al. 2022). We were unable to study the influence of many often-reported biases in grant systems. For example, racial disparity in grant peer review and awards is well documented. However, because these data were not routinely collected by CIHR during the timeframe under consideration, we were unable to include self-identified race or ethnicity as factors in this analysis.