Excavating the regulatory process and risks posed by Alaska hardrock mine expansions

Abstract

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Methods

Study sites

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acid mine drainage | Wastewater from mining activities that has become acidic due to oxidation of sulfides |

| Heap leach | Process that uses chemicals to irrigate crushed, low-grade ore to extract the mineral commodity of interest, such as gold or silver |

| Mill | A facility where ore is ground to a reduced particle size and valuable metals are removed via physical or chemical treatment |

| Mining slurry | Crushed ore that is mixed with water in a mill |

| Open pit mine | Mining operation removing minerals entirely from the surface |

| Ore | Solid material containing the commodity of interest, such as gold or silver |

| Reclamation | Actions designed to make a mine that has ceased operations blend in with the surrounding landscape and possibly become usable land; often includes restoration and environmental monitoring efforts |

| Tailings | Waste product resulting from processing ore; not to be confused with waste rock |

| Tailings storage facility | Tailings are stored in either reservoirs as a saturated slurry or dry stacks after most water content has been removed |

| Underground mine | Mine whose footprint is mainly underground in shafts and tunnels to access ore deposits |

| Waste rock | Rock that has little to no ore that must be removed to access ore |

Note: The definition of heap leach was paraphrased from Ghorbani et al. (2016), while the remaining definitions were paraphrased from Dunbar (2024). We refer readers to more detailed descriptions of mining in Whyte and Cumming (2007) and Dunbar (2024).

| Term | Law | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Alternatives | NEPA | Each proposed action is accompanied by various alternatives that may produce different environmental outcomes; among these alternatives are the “preferred” alternative and the “no action” alternative |

| Environmental assessment (EA) | NEPA | Analysis that determines whether or not a federal action has the potential to cause significant environmental effects; can result in finding of no significant impact or EIS |

| Environmental impact statement (EIS) | NEPA | Robust analysis of the impacts (e.g., social, ecological) of a proposed action; first published as a draft EIS, then undergoes a public comment period, after which the draft is amended into a final EIS that responds to comments |

| Essential fish habitat | MSFCMA | Waters and substrate necessary for fish spawning, breeding, feeding or growth to maturity (16 U.S.C. §§ 1801 et seq.) |

| Fill material | CWA | Rock, sand, dirt, or other material necessary for the construction of any structure in waters of the U.S. (43 CFR § 232) |

| Finding of no significant impact | NEPA | Document that presents reasons why the agency has concluded that no significant impacts are projected for a particular action |

| Notice of availability | NEPA | Announcement in the Federal Register that the prepared EIS (draft or final) is available |

| Notice of intent | NEPA | Public announcement in the Federal Register that informs the public of an upcoming environmental analysis, describes how the public can become involved, and initiates the scoping period |

| Plan of operations | BLM/USFS mining regulations | Document describing proposed operations with sufficient details to determine whether activities would cause “unnecessary or undue degradation” of public lands (43 CFR § 3809.401 and 36 CFR § 228.3). |

| Record of decision | NEPA | Document that explains the agency's decision, describes the alternatives considered, and discusses agency's plans for mitigation and monitoring as necessary |

| Supplemental environmental impact statement (SEIS) | NEPA | Analysis of a substantial proposed change to a previous action (i.e., EIS); follows the same process as an EIS |

Note: Definitions are paraphrased from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (https://www.epa.gov/nepa/national-environmental-policy-act-review-process) unless otherwise stated. NEPA = National Environmental Policy Act; MSFCMA = Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act; CWA = Clean Water Act.

| Agency | Jurisdiction | Role | Relevant case study |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) | Federal | Oversaw ESA and MMPA compliance | Greens Creek, Kensington |

| U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) | Federal | Administered Clean Water Act §404 permit | Fort Knox, Greens Creek, Kensington, Pogo, Red Dog |

| U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) | Federal | Lead agency on SEIS (Red Dog Aqqaluk); NEPA cooperating agency (Greens Creek, Kensington); CWA implementation or oversight; CAA oversight | Greens Creek, Kensington, Red Dog |

| U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) | Federal | Oversaw ESA and major wildlife act compliance | Greens Creek, Kensington, Red Dog |

| U.S. Forest Service (USFS) | Federal | Lead agency on SEIS, issued record of decision; approved mine expansion plan of operation | Greens Creek, Kensington |

| Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (ADEC) | State | Oversaw compliance with CWA and CAA permitting (Greens Creek, Kensington) | Fort Knox, Greens Creek, Kensington, Pogo, Red Dog |

| Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) | State | Oversaw fish habitat protection and passage permitting | Greens Creek, Kensington, Red Dog |

| Alaska Department of Natural Resources (ADNR) | State | Lead agency on State of Alaska permitting and reclamation plan approval | Fort Knox, Greens Creek, Kensington, Pogo, Red Dog |

| City and Borough of Juneau (CBJ) | Municipal | Participated in NEPA/SEIS process | Greens Creek, Kensington |

Note: The agency column is sorted alphabetically within each jurisdiction (federal, state, municipal). Acronyms related to laws and policies listed in the Role column are defined in Table 4.

| Law or policy | Year passed | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act | 1980 | Establishes protections within Admiralty Island National Monument |

| Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act | 1940 | Regulates protection of bald and golden eagles |

| Clean Air Act (CAA) | 1963 | Regulates all sources of air emissions |

| Clean Water Act (CWA) | 1972 | Regulates discharge of pollutants into U.S. waters; Defines the terms of the National/Alaska Pollutant Discharge Elimination permits |

| Endangered Species Act (ESA) | 1973 | Regulates compliance with Section 7 interagency consultation |

| Executive Orders 11988, 11990, 12898, 12962, 13077, 13112, 13175 | Varies | Regulates project compliance with all Federal executive orders |

| Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act | 1934 | Regulates impacts on fish and wildlife |

| Freedom of Information Act | 1967 | Requires the partial or full disclosure of U.S. governmental documents |

| Forest Plan | 2008 | Guides forest management and conservation efforts |

| Forest Service Roadless Area Conservation Rule | 2001 | Regulates protection of roadless areas within National Forest System lands |

| General Mining Law | 1872 | Allows U.S. citizens to explore for and purchase certain mineral deposits on federal land where mining is allowed |

| Greens Creek Land Exchange Act | 1995 | Allows Tongass National Forest land to be explored and developed for mining |

| Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) | 1972 | Regulates compliance with Section 7 interagency consultation |

| Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSFCMA) | 1976 | Regulates compliance with Section 305 consultation |

| Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) | 1918 | Maintains populations of all protected migratory bird species |

| National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) | 1970 | Establishes framework to guide agency assessment of environmental impacts of proposed decisions |

| National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) | 1966 | Regulates Section 106 compliance |

| Wilderness Act | 1964 | Establishes national network of federally designated and managed wilderness areas |

| Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act | 1971 | Conveys over 45 million acres (>18 million ha) of land to village and regional Native corporations |

| City and Borough of Juneau Comprehensive Plan | 2008 | Outlines approach to community growth and development of CBJ |

| City and Borough of Juneau Exploration and Mining Ordinance | Varies | Establishes how federal, state, and local mining ordinances coordinate |

Note: The law or policy column is sorted alphabetically within each hierarchical jurisdiction (i.e., federal to municipal). This table should not be considered a comprehensive list of all laws and policies related to mining operations in Alaska.

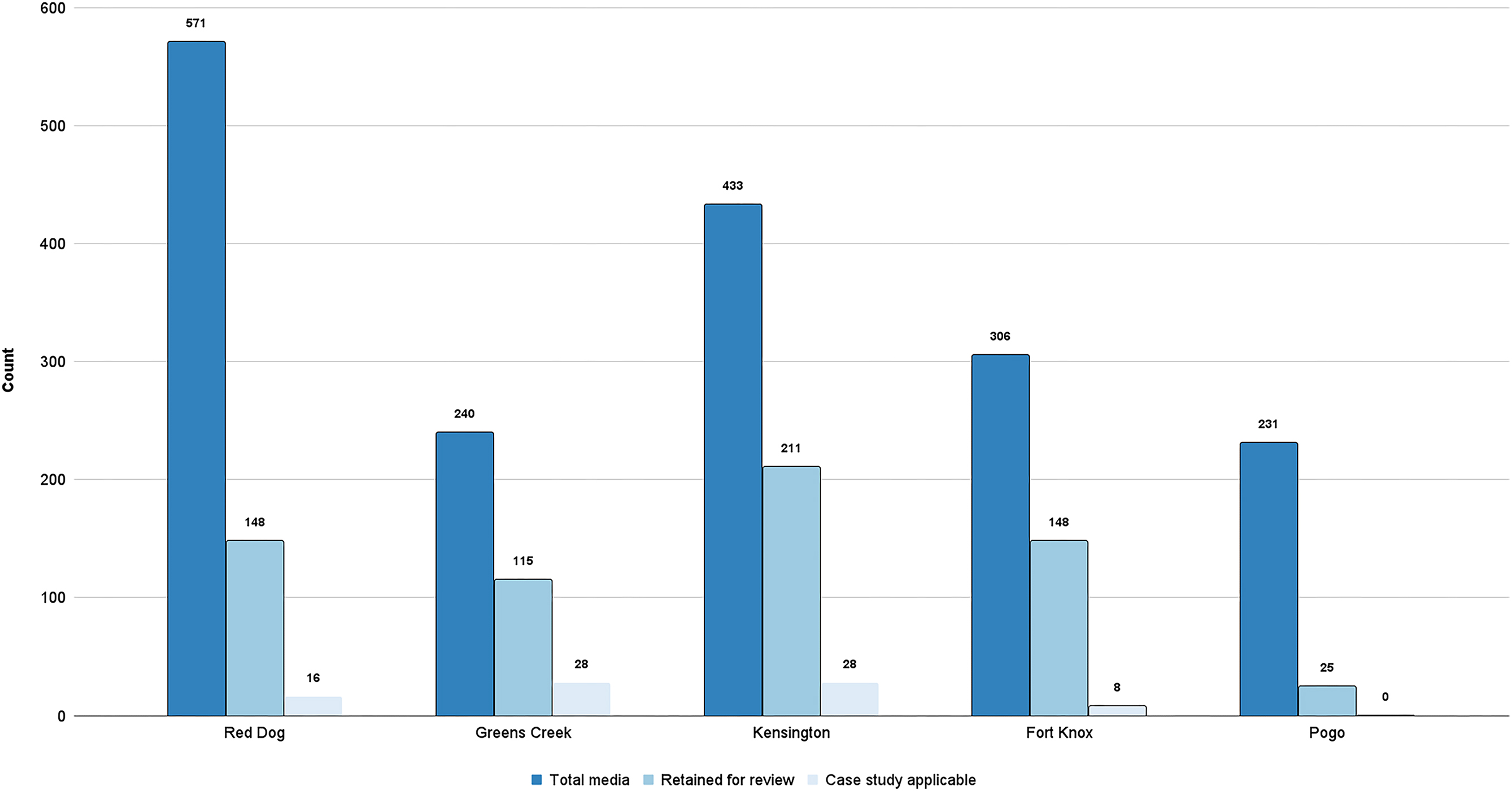

Case study approach

Selection of case studies

Results

Red Dog case study

History, setting, and operations

| Red Dog1,2,3,4 | Greens Creek5,6,7,8,9 | Kensington10,11,12,13 | Fort Knox14,15,16 | Pogo17,18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | 68.07, −162.85 | 58.13, −134.75 | 58.85, −135.09 | 65.00, −147.34 | 64.45, −144.90 |

| Materials mined (2022 production) | Zinc (553 100 mt) | Silver (9741 935 oz) | Gold (109 061 oz) | Gold (291 249 oz) | Gold (215 671 oz) |

| Lead (79 500 mt) | Gold (48 216 oz) | ||||

| Zinc (52 312 mt) | |||||

| Lead (19 480 mt) | |||||

| Operational aspect | Open pit | Underground | Underground | Open pit | Underground |

| Year original EIS published | 1984 | 1983 | 1992 | 1993* | 2003 |

| Commenced production | 1989 | 1989 | 2010 | 1997 | 2006 |

| Year of public notice for the case study SEIS | 2007 | 2010 | 2020 | 2001* | 2020/2022† |

| Current ownership | Teck Cominco Alaska | Hecla Greens Creek Mining Company | Coeur Alaska | Kinross Gold | Northern Star Resources |

| Land ownership and management | NANA Regional Cooperation | United States Forest Service | United States Forest Service | State of Alaska Department of Natural Resources | State of Alaska Department of Natural Resources |

| Number of employees (2022) | 644 | 491 | 395 | 732 | 610 |

| Annual revenue (2022 in millions USD) | $2111 | $335 | $183 | $522 | $363 |

| Financial assurance (millions USD; current as of 2022) | $629 | $92 | $43 | $102 | $72 |

Note: oz = ounces; mt = metric ton.

References: 1. Teck Resources Limited (2023); 2. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Department of the Interior (1994); 3. Alaska Department of Natural Resources (2022); 4. Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (2018); 5. U.S. Forest Service (1983); 6. U.S. Forest Service (2013); 7. Hecla Mining Company (2022a); 8. Hecla Mining Company (2022b); 9. Hecla Mining Company (2020); 10. Coeur Mining (2021); 11. U.S. Forest Service (1992); 12. Coeur Mining (2022); 13. Alaska Department of Natural Resources, Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation, and U.S. Department of Agriculture (2017); 14. Fairbanks Gold Mining, Inc. (1993); 15. Fairbanks Gold Mining, Inc. (2023); 16. Kinross Gold Corporation. (2023); 17. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2003); 18. Northern Star Resources Limited (2022).

Key expansion issue

Public process, tribal engagement, and agency response

Summary

Greens Creek case study

History, setting, and operations

Key expansion issue

Public process, tribal engagement, and agency response

Summary

Kensington case study

History, setting, and operations

Key expansion issue

Public process, tribal engagement, and agency response

Summary

Fort Knox case study

History, setting, and operations

Key expansion issue

Public process, tribal engagement, and agency response

Summary

Pogo case study

History, setting, and operations

Key expansion issue

Public process, tribal engagement, and agency response

Summary

Synthesis of key findings across case studies

Discussion

Varied permitting processes, degree of engagement, and public concerns

Cumulative effects analysis

Challenges in accessibility of the public process

Role of NEPA and public involvement in mining expansions

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

Supplementary material

- Download

- 22.93 KB

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Copyright

Data Availability Statement

Key Words

Sections

Subjects

Plain Language Summary

Authors

Author Contributions

Competing Interests

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Other Metrics

Citations

Cite As

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

There are no citations for this item