Graduate student experiences and perspectives related to conducting thesis research within long-term ecological projects

Abstract

Long-term ecological research (LTER) projects are considered valuable training grounds for graduate student researchers, yet student voices are largely absent from discussions of LTER merits in the literature. We aimed to identify benefits and challenges encountered by current and former graduate students in conducting graduate research within LTER projects. To explore graduate student experiences and perspectives, we conducted a survey comprising both closed-ended questions (i.e., multiple choice and Likert scale) and open-ended questions. From the responses, we identified emergent categories related to positive and negative experiences using sentiment analysis. We found agreement with purported benefits in areas including networking and access to established field sites and protocols. However, participants also identified data accessibility, authorship decisions, communication, and interpersonal conflicts as significant sources of challenges. We synthesized survey results with existing literature to provide actionable recommendations for principal investigators in four main areas (data, authorship, communication, and management) through an LTER lens. In addition to providing longitudinal data, LTER projects offer graduate students both physical and methodological infrastructure that can serve as the scaffold for new research questions to be developed. However, the likelihood of success of student research, as well as the success of the students themselves, can be improved when the needs of graduate students are prioritized.

Introduction

Long-term ecological research (LTER), characterized as the regular monitoring of a given set of variables in natural systems over many years, has proven to be a valuable and productive approach to understand patterns and disentangle ecological and evolutionary relationships (Tinkle 1979; Lindenmayer et al. 2012; Hughes et al. 2017; Kuebbing et al. 2018; Vucetich et al. 2020). Long-term studies of natural systems offer unparalleled opportunities to follow individuals, populations, and abiotic variables across variable conditions, acquire repeated observations for individuals across organismal lifespans, and provide insight into the potential drivers behind population trends, ecosystem dynamics, and evolutionary changes (e.g., Lack 1964; Armitage 1991; Clutton-Brock and Sheldon 2010; Dantzer et al. 2020). Resulting datasets may also augment short-term field manipulations to allow inferences to be placed into a broader context (e.g., Krebs 1991), permit study replication (e.g., Pace et al. 2019), and may be analyzed a posteriori to ask new questions of old data (e.g., Lindenmayer et al. 2012). Collectively, LTER is also increasing our capacity to study global patterns (e.g., International Long Term Ecological Research Network, Vanderbilt et al. 2015; USA LTER Network, Hobbie et al. 2003; SPI-Birds, Culina et al. 2020). As a result, contributions of research conducted in LTER projects to science and policy have been identified as being disproportionately large (Hughes et al. 2017).

LTER projects also serve as training grounds for many ecologists and evolutionary biologists. A survey of 92 long-term projects worldwide reported the involvement of 658 postgraduates and 257 postdoctoral fellows on projects ranging in length from 5 to 68 years (Mills et al. 2015). Long-term research projects are perceived to provide “excellent opportunities for undergraduate and graduate study and research” (Waide and Kingsland 2021, p. 51) with access to existing protocols, permits, established field sites and research stations, years of standardized data collection, and knowledgeable predecessors and/or collaborators. Connections to broader networks of sites and researchers, and the associated capacity for interdisciplinarity in collective research, are further supposed benefits of conducting graduate studies in such frameworks (Swank et al. 2001). Indeed, the International Long Term Ecological Research Network explicitly included the training of future long-term scientists as one of its primary goals (Gosz et al. 2010). Given that ecology PhD recipients generally see a high recruitment rate into academic positions (68.2% of employed ecology PhD recipients; Hampton and Labou 2017), many involved in LTER projects may continue to benefit at the tenure-track level (Waide and Kingsland 2021), in turn training the next generation of scientists.

Examples of challenges documented in non-LTER scenarios include bridging cross-disciplinary work with various collaborators (Romolini et al. 2013), navigating fieldwork as a novice (Leon-Beck and Dodick 2012), and managing mental health and well-being (Evans et al. 2018; but see Swank et al. 2001). Many of these challenges are likely to also be present in LTER projects given shared characteristics (e.g., collaboration, fieldwork, etc.). The nature of LTER projects in involving multiple years of data collection (and therefore, protocol consistency and data management), and often multiple researchers and field technicians across time, may introduce additional challenges that may not be encountered in non-LTER projects. While LTER projects have demonstrable benefits to science and individual career advancement, some of these benefits, such as access to archived datasets and collaborations involving multiple principal investigators (PIs), may come with hidden costs shouldered by trainees.

The voices of graduate student trainees is largely missing from the published discourse on LTER training. Indeed, keyword searches conducted in Web of Science and JSTOR in July 2023 for (“graduate student” and “long-term research”) or (“graduate student” and “long-term ecological research”) in all search fields yielded only 20 articles, which when checked, were not of topical relevance. Seemingly, the value that graduate students bring to LTER projects through their intellectual contributions and ideas for new directions, as well as the purported benefits derived from training in LTER projects, are highlighted by PIs on such projects (e.g, Hobbie et al. 2003; Waide and Kingsland 2021) rather than by graduate students themselves.

Here, we explored potential benefits and challenges experienced by past and current graduate students conducting thesis research within an LTER project, through a voluntary survey. We aimed to identify, not only benefits and challenges, but also motivations for joining a given LTER project. We synthesized the literature and the survey results to offer actionable recommendations to improve graduate student experiences within LTER frameworks.

Materials and methods

Context

In 2017, a symposium for long-term research in Canada was held to mark 70 years since the opening of the Algonquin Wildlife Research Station (Wildlife 70 Symposium, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario). Delegates to the symposium produced a statement that recommended the establishment of a LTER network across Canada to foster collaboration, communication, and ongoing support. To lay the foundation of the proposed network, the Section for Long-Term Research within the Canadian Society for Ecology & Evolution (LTR-CSEE) was established in 2018 and the section held its first symposium in 2019 (co-organized by author AEW; author MRB participated as a panelist). The inclusion of graduate student voices is considered fundamental to the development of the proposed network and was the motivation for investigating perspectives to facilitate discussion in the ensuing 2019 symposium. We designed a survey to investigate the experiences of graduate students to provide preliminary sentiments and areas for discussion at the symposium, which we then formally analyzed and present in the present study. We, the authors, acknowledge participation in LTER throughout our doctoral research (see conflict of interest statement below). Each of us have contributed to the collection of long-term project data over multiple field seasons, in addition to auxiliary data specific to our graduate thesis research. We have each published collaborative papers using long-term project data. While we have benefited personally and professionally from these experiences, we also empathize with some of the challenges expressed regarding graduate student experiences and were thus motivated to formally explore them more broadly. Against the backdrop of establishing a national LTER network in Canada, our intention with this survey-based study was to listen to and elevate the voices of graduate students in the conceptualizations of “best practices” for LTER and graduate research broadly.

Survey design and distribution

We invited current and former graduate students to complete our voluntary survey if they had conducted at least part of their graduate thesis research in conjunction with an LTER project. Although our experiences and connections are primarily within or linked to Canada, we did not restrict the survey based on geographic location (see survey distribution details below). To gain a wide variety of opinions, participants could complete the survey irrespective of current position or thesis project status (i.e., completed or in progress).

The survey, designed in consultation with a social scientist with experience in survey design, comprised 43 questions, including multiple choice questions, multiple answer questions, Likert scale questions, and open-ended questions, which could be filled out with written statements (see Supplementary Online Material File 1 – Survey Questions). The survey and survey methods were approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Saskatchewan Approval #1283. The first two questions asked about the respondent’s current position, for which degree program they were involved in a LTER project, and approximately what proportion of the graduate project relied on core data collected by the LTER project. Multiple choice questions assessed respondents’ career stages, degree types, and the extent to which their research depended on LTER data. Participants were then asked to answer all remaining questions “with your most recent long-term research project experience as a graduate student.”

The survey questions were founded on core categories we anticipated to be of significance (e.g., data, authorship, communication, collaboration, etc.) based on the literature, our own experiences, and collegial discussions. Likert questions addressed topics including project development, support, data use and protocols, authorship, communication, capacity for future work, and professional development. Participants responded using a 5-point Likert scale where 1 indicated strong disagreement and 5 indicated strong agreement. Short answer questions asked participants to list an (1) unexpected potential benefit, (2) unexpected challenge, and then specifically (3) an authorship related concern and (4) data related concern. We also provided an open comment box for short-answer questions and an “other” option for multiple choice questions to allow participants to express sentiments that were not captured by our predetermined questions.

Participants could skip questions and no information was gathered related to participant identity (i.e., name, gender, and ethnicity) or details that could link individuals to specific projects (e.g., study species, field site location, institutions, time since graduation, etc.) to protect participants, especially those that are currently enrolled as graduate students, and to obtain the most honest information possible without fear of retribution. We acknowledge that individual experiences may vary along axes of identity including (but not limited to) gender and ethnicity, and that we could not examine these trends as data were purposefully not collected here for reasons stated above.

We administered the survey through Survey Monkey (www.surveymonkey.com) and accepted responses for 1 month, from 1 July to 1 August 2019. The survey was distributed in English, through existing contact networks via email (including PIs in North America and Europe known to lead LTER projects in North America, Europe, Australia, and Africa), and through social media (primarily Twitter). Recipients of the survey announcement were encouraged to in turn share the invitation with their contacts, including current and former students, to further the reach. We acknowledge this likely biased our sample to individuals currently active in research or research-adjacent positions, and likely toward North American and European participants. However, we are confident that our survey captures sentiments that allow for the initiation of formalized discussions amongst research groups and institutions on ways to bolster benefits and mitigate potential drawbacks to students within their LTER programs and thus, helps guide the lines of inquiry for further comparative and cross-sectional studies.

Analysis

We summarized responses to multiple choice questions as a percentage of respondents that selected each option, including any responses to the “other” option. Questions requesting a response using Likert scale structuring (scale of 1–5) were not symmetrical around topics or sentiments. Therefore, for each of these questions, we transformed the number of responses at each level of the Likert scale into a percentage (e.g., 25% responded with a rating of 1). We then tested for correlations among five broad topics (Supplementary Tables 1–5) using Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and averaged percentages across questions with correlation coefficients ≥0.7 to prevent reporting duplicate response sentiments. Short answer responses and responses under the “other” option for multiple choice questions were analyzed using methods adapted from ground theory, a methodology for identifying emergent categories within survey responses (Charmaz 2014). We identified main categories and sub-categories through a two-step coding procedure (Hay 2005) whereby two reviewers independently coded responses into major categories and then, based on comparisons across reviewers, further categorized responses into focused sub-categories, where applicable. To mitigate acquiescence bias (i.e., associate positivity with the question statement, potentially masking the respondents true position), participants were coded only when they explained their experience (Newing 2011). Using this framework allowed us to contextualize the data while also allowing for participants’ unique experiences to be represented. Both Likert responses and categories derived from short answer responses are presented in terms of their prevalence across respondents (per Sandelowski 1998).

Results and discussion

Past studies have described the impact of LTER projects on the advancement of scientific knowledge (e.g., Clutton-Brock and Sheldon 2010) and the training of the next generation of biologists (Waide and Kingsland 2021). Here, we explored the graduate student experience within LTER projects through survey results from 127 participants. On average, 76% of the survey was completed by participants (given they could skip questions). We were able to obtain a broad sample across current career stages (n = 112 for this question) with 21 Master’s students (19%), 39 PhD students (35%), 21 postdoctoral fellows (19%), 16 professors (14%), four government agency scientists (<1%), and 11 people who worked outside academia or a government agency (1%). Our sample was also split across degree types performed in an LTER program, with 50% of the participants having conducted their PhD (n = 55), 29% their Masters (n = 32), and 22% both their Masters and PhD (n = 24) in conjunction with a LTER project. Reliance on the LTER core project data (n = 112) was also highly variable, with one third of graduate projects (n = 38) relying completely on the LTER project data while 29%, 19%, 13%, and 4% relied only 75% (n = 33), 50% (n = 21), 25% (n = 15), and 0% (n = 5) on the data collected within the LTER project, respectively. Given that answers came from participants currently in various career stages and who conducted LTER research in different degree programs (Master’s and PhD) with variation in reliance on LTER data, we are confident we obtained a wide variety of experiences and believe their convergence on response categories adds weight to topic importance. Below, we discuss some of these major categories that emerged from our survey. Note that for the quotes, we have provided lightly copyedited text where necessary for clarity or to maintain anonymity while maintaining the original sentiment.

Motivations for joining LTER

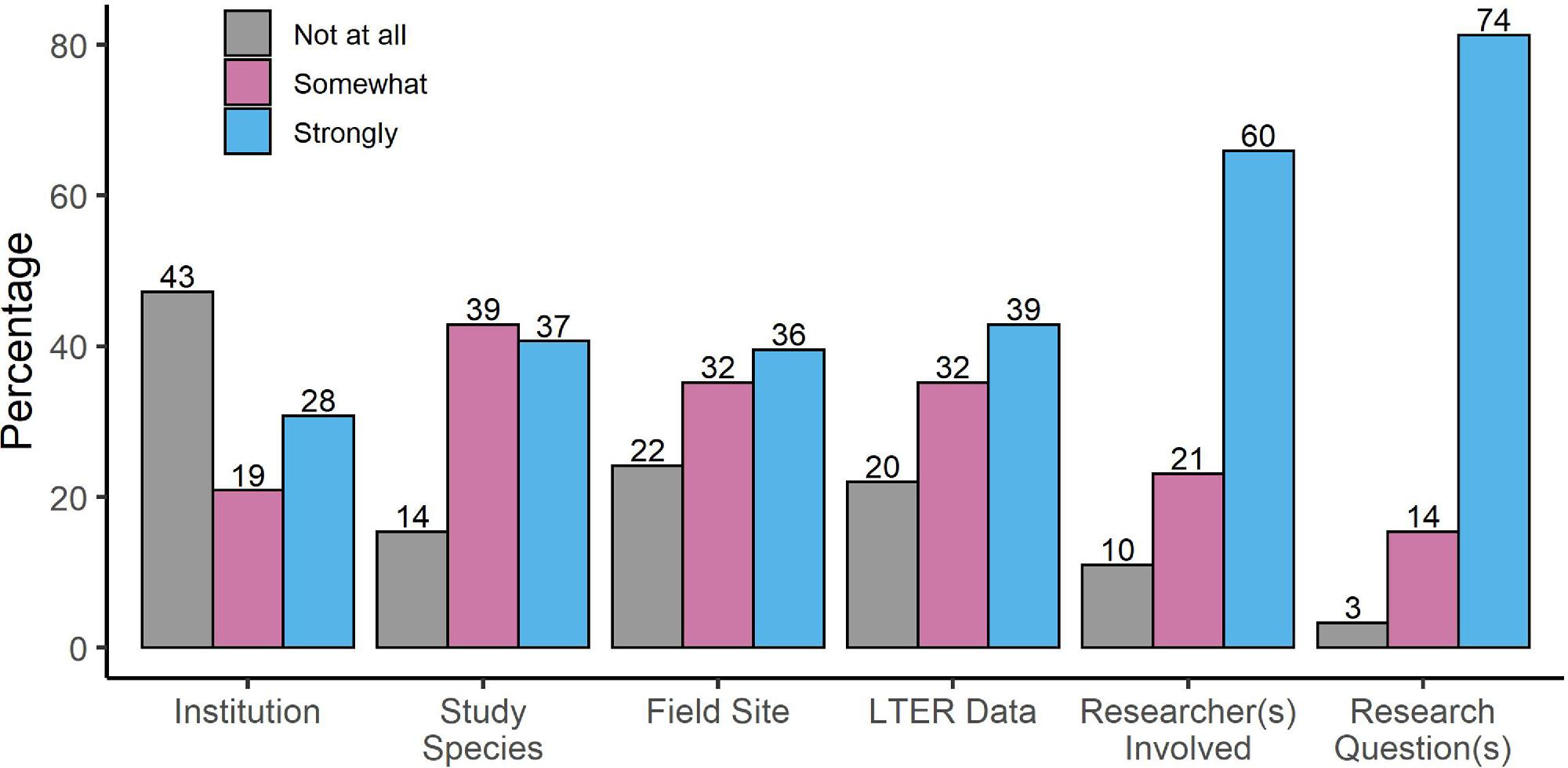

We asked participants to rank the strength of influence of their motivations for choosing to work with a particular LTER project. The two strongest motivators were the potential research questions being addressed in the LTER and the researchers involved in the project, with 74% and 60% of participants, respectively, saying it strongly influenced their decision (Fig. 1). Other project-related elements, including the long-term data, study species, and field site were identified as moderate motivators, with 39%, 37%, and 36% of participants, respectively, indicating these factors motivated their choice to join the LTER project (Fig. 1). The institution affiliated with the LTER project did not motivate the decision for 63% of participants (Fig. 1). Finally, six individuals chose “other” as a motivator, specifying availability of funding (n = 3), the supervisor (n = 2; e.g., “picked a PI at a great institution with funding”), or previous affiliation with the project (n = 1) motivated their choice. As such, the reputation of the LTER project and the researchers involved were more influential than institutional or program choice, which should be noted both by researchers and by institutions themselves looking to recruit graduate students.

Fig. 1.

Benefits of conducting graduate research in an LTER project

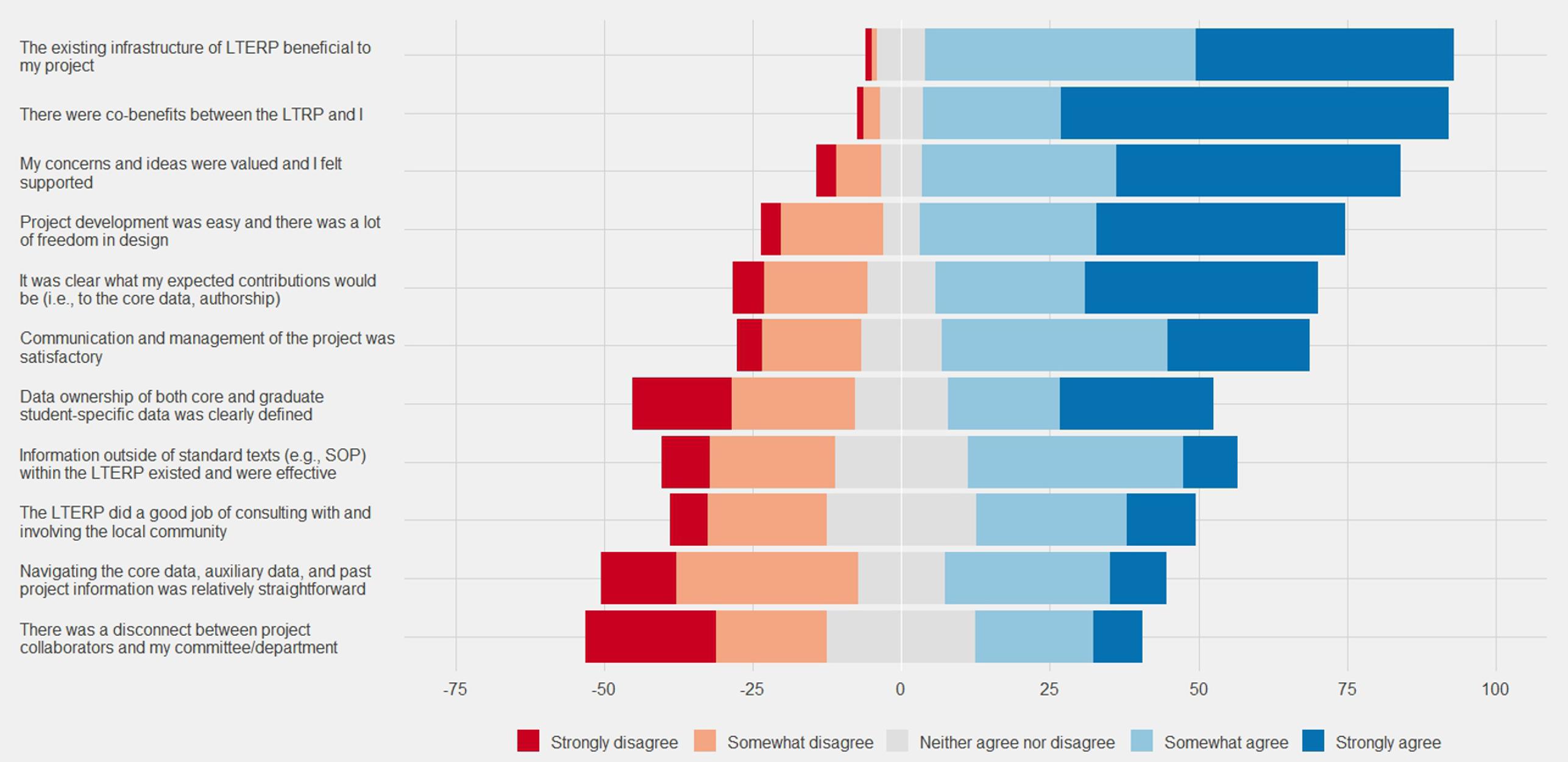

Consistent with previous data and assertions in the literature (e.g., Gosz et al. 2010; Waide and Kingsland 2021), we found the perceived benefits to be broad and numerous. Sentiments expressed through Likert questions were generally positive, indicating clear benefits to working within an LTER project (89% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that LTER participation is co-beneficial). These benefits included support in project development (72% agreed or strongly agreed), the existing infrastructure of the project (89% agreed or strongly agreed), and the built-in support system (i.e., participants felt valued and supported within the LTER project, with 81% agreeing or strongly agreeing; Fig. 2). There was moderate agreement toward there being clear expectations for expected contributions toward data collection for core LTER project and publications (65% agree or strongly agree). We found moderate agreement for clear communication and management more generally (62% agreed or strongly agreed; Fig. 2). This led to respondents being in favour of involvement with long-term research at a future stage of their career (88% agreed or strongly agreed) and participants generally felt like they would positively recommend LTER projects to other graduate students (87% agreed or strongly agreed; Fig. 2; Supplementary materials). These sentiments confirm the perception that LTER projects act as training opportunities as claimed (Gosz et al. 2010), and demonstrate that they are indeed experienced as such, and in a positive manner, by the trainees themselves.

Fig. 2.

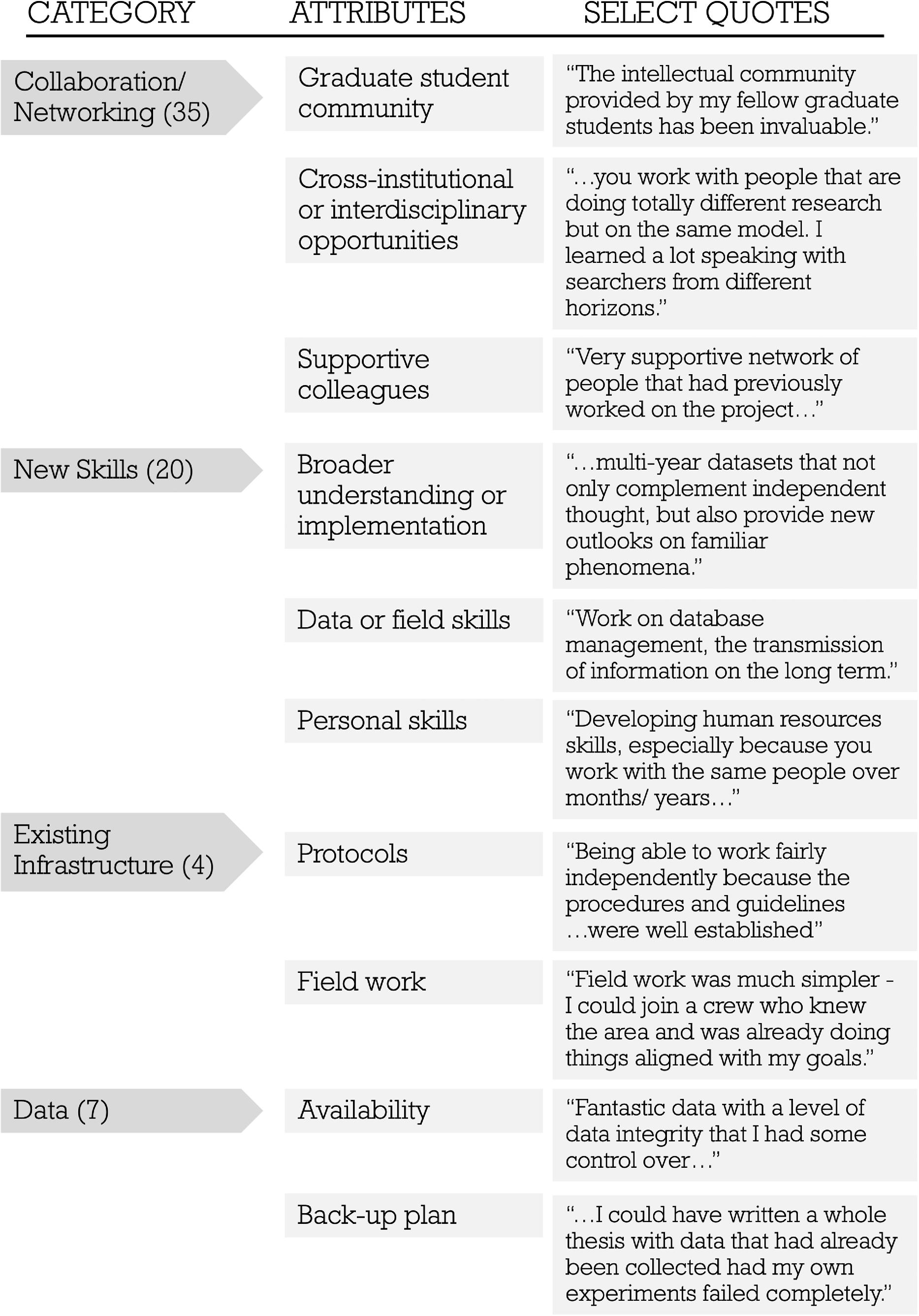

The general benefits identified in the Likert questions also translated to our thematic analysis, where we identified four major categories of unexpected benefits participants (n = 66) gained from working within an LTER project: (1) networking and collaboration (n = 30), (2) developing new skills (n = 23), (3) existing infrastructure (n = 4), and (4) project data (n = 7; Fig. 3). Participants who indicated they benefited from collaboration and networking opportunities were the most prevalent (45% of responses) given they were able to work with a multitude of graduate students, institutions, or disciplines; there was a general sense of support and community arising from working within a collaborative network (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

“I feel very fortunate to have taken part in a very long term [taxon] study. I felt tied to researchers who had been part of the study before me, and went on to work on other long term research studies partly because of this fact. It was good for my connections and network development, it was good for my understanding of an ecological system, and it was good for my thesis and development as a scientist".

“I am on the whole exceedingly lucky to have been steeped in a rich ecological history, which comes from the LTRP I am a part of. There are direct connections to fascinating lines of inquiry and a community of great support and caliber. All collaborations come at the cost of navigating difficult personality conflicts. But, that is a cost well worth the benefit of observing an ecosystem on a time scale greater than can be observed by one person alone”.

The development of new skills was the second most prevalent category (35% of responses), with skills acquired including conceptual skills related to perspective and thought within the field, technical skills related to fieldwork or data analysis, and personal skills such as interpersonal development, communication, and developing work-life balance (Fig. 3). The benefits of existing infrastructure (6%) and long-term data (11%) were less prevalent thematically, but responses indicated that these benefits allowed participants to learn from established protocols and experienced people, and that data sample size and its utility as a back-up plan was useful in the event that there were failures with other aspects of the student’s project (Fig. 3).

“It gave me a sense of security in the sense that I knew data already existed. It allowed me to concentrate more on the questions and the methods related to my project rather than worrying about data aresues”.

The above sentiments point to LTER programs offering a multitude of support systems, both in terms of personal support (e.g., mental health, networking, and skill sharing) and research support (through established protocols, infrastructure, datasets, and knowledgeable collaborators; Waide and Kingsland 2021). It seems likely that these support systems contribute to the general feelings of positivity, and perhaps even augment mental health or provide a sense of security. Some sentiments under the skill acquisition category also imply that being a part of LTER may also produce researchers that have a broader foundation in the field; for example:

“…I believe LTERs promote a grander view of biological sciences among students. As opposed to thinking about research along a timeline of a handful of years (the life of a graduate project), students are encouraged to think far into the future, which stokes ambition for larger scientific ventures. This shift in perspective likely broadens the scope of questions they grapple with, and might aid in the transition to faculty positions which necessitate a comprehensive research plan that spans the duration of their academic career “.

Thus, the benefits of LTER participation for graduate students should not be understated, and LTER programs should aim to augment and strengthen the clear personal and research-based benefits that come as a result of being established and often collaborative programs.

Challenges in conducting graduate research with an LTER

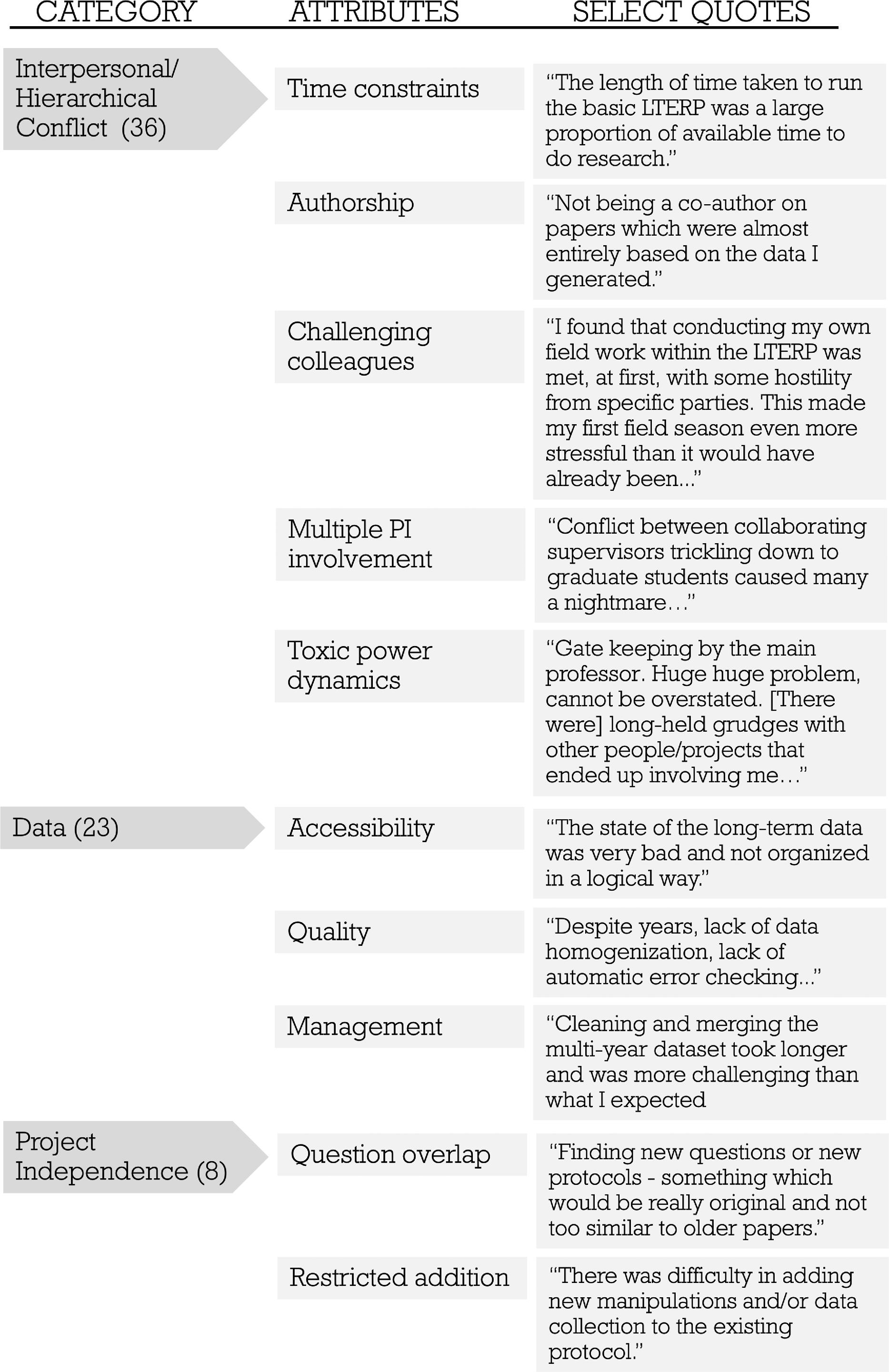

Based on Likert questions, participants expressed a more negative outlook when it came to local community consultation (34%), navigating various forms of project data (e.g., core and auxiliary datasets; 37%), accessing information outside standard texts such as available protocols or publications (e.g., past research that did not yield a published paper; 46%), and data ownership (45%; Fig. 2). While we tailored Likert questions to topics expected based on the literature and our own experiences, given the opportunity to expand in short answer questions (n = 67), participants identified challenges within categories mostly focused on interpersonal conflict (n = 36), with fewer related to data and project issues (n = 23 and 8, respectively; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

In text responses to the question asking what unexpected challenge was faced, interpersonal and/or hierarchical conflicts was the most prevalent category (54% of responses spoke about this issue). This main category was related to five sub-categories including (1) prioritization of core LTER project needs over individual graduate projects resulting in time constraints on independent graduate student work (n = 6), (2) the exclusion from or granting of unjustifiable authorship (n = 4), (3) dealing with challenging colleagues (n = 5), and (4) navigating divergent priorities, poor communication, or the politics among multiple PIs (n = 9; Fig. 4). There were concerning responses from multiple participants who identified toxic power dynamics (n = 4) related to territorial or gatekeeping behavior, sentiments which unfortunately are seen in science more broadly (Fig. 4; Tuma et al. 2021).

“Power dynamics are difficult to navigate. I am reluctant to visit one of the field sites because of an abusive personality. Managing a relationship with the field site has been challenging”.

The second most prevalent category had to do with data related challenges (34% of responses) with sub-categories related to: (1) accessing data, including lack of clear documentation on data collection and structure (n = 10), (2) data quality, given the way the data were stored, collected by multiple people, or the lack of data cleaning (n = 7), and (3) excessive time being spent on data management related to cleaning, manipulating, or merging various forms of the LTER datasets (n = 6; Fig. 4). Finally, project independence was the last major category to come out of respondent answers (12% of responses), which was also a challenge for some participants given they had a hard time coming up with new questions that were not already published (n = 7), or had been answered in unpublished work that new students did not know existed (n = 1; Fig. 4).

When asked specifically about data related concerns, participants (n = 66) primarily responded with concerns around data quality and consistency (n = 29, 44%), with sub-categories arising from many different people collecting over the years (12%), and lack of standardized protocols or methodological creep over the length of the LTER project (24%; Table 1). A second major concern was related to accessibility (n = 17) through an inability to locate data or access data (53%), or lack of protocols and metadata to explain the data collection (29%; Table 1). Finally, a less prevalent concern was related to long-term data ownership (n = 10) given the efforts put into data collection (Table 1). Only six of 66 participants had no data-related concerns.

Table 1.

| Concern | Illustrative responses |

|---|---|

| Data | “Relying on the core dataset from previous years means that I am wholly reliant on data that is collected by researchers I have never met. There is a fair amount of trust that goes into that”. |

| “I find it difficult to access past data that belongs to other graduate students but is essential to my project”. | |

| “Methodological creep: that the methods used by one person might differ in ways that people don't realize or write down, such that methods change over time without people noticing”. | |

| “Who does my data belong to? And how long does that ownership agreement last”? | |

| Authorship | “Authorship criteria are nebulous, i.e., when a past collaborator/student/researcher should or should not be on a paper. Is there a time limit beyond which authorship should be replaced by acknowledgement or citation to a paper”? |

| “N/A. I think as long as the authorship expectations are outlined from the start, that some conflict can be averted”. | |

| “I have not had too many negative experiences surrounding authorship, but I did find that when collaborative projects within an LTERP are mentioned to all included, if you express interest in contributing as a graduate student, you're often ignored”. | |

| “Since the LTERP is well established, there are clear lines between each student's work while allowing us to share our data to reach our respective objectives”. |

When asked specifically about authorship related concerns, there were five major categories (Table 1). Above all else, there was a call for clear guidelines to be established (n = 18; Table 1). In descending prevalence, participants also had inclusion-related concerns (n = 18; i.e., lack of student inclusion and/or including others with questionable authorship merit), navigating the differing opinions of multiple PIs (n = 3; i.e., through differing writing styles or ideas on project direction), overlap among publications due to multiple student involvement (n = 2) and one instance of conflict of interest in publishing results not in line with what was desired by the funding body (Table 1). Twenty-two of 66 participants had no authorship-related concerns, particularly when expectations were clearly set out ahead of time.

Some challenges identified here are certainly not unique to LTER projects. For example, the scientific literature is rife with examples of data-related calls for transparency and replicability across all fields (e.g., Baker 2016). Interpersonal and hierarchical conflicts are pervasive in the workforce in general and navigating such conflicts in an academic setting require skills that are not as prioritized in traditional natural science training (Hund et al. 2018), such as mentorship, effective non-scientific communication, and conflict resolution. The scope of the remaining issues (data and authorship) have been discussed in terms of proper data archiving (Mills et al. 2015; Evans 2016), reproducibility (Pace et al. 2019), and data preservation and rescue for future generations (e.g., the Canadian Institute of Ecology & Evolution’s Living Data Project; Bledsoe et al. 2022). Additionally, authorship guidelines have been discussed in a general sense (Vancouver Convention, updated 2021), and more specifically for data contained in data repositories (Wallis and Borgman 2011) and in relation to long-term projects (Huang et al. 2020).

Potential benefit–challenge relationships

Further exploration of benefits and challenges within individual responses revealed emergent benefit–challenge pairs. Of the respondents who indicated collaboration and networking as a benefit, 16 identified interpersonal or hierarchical conflict as a challenge, 12 had data issues, and six had challenges with project independence. For example, one participant who identified “building a network of collaborators” as an unexpected benefit went on to identify an unexpected challenge being ‘integrating my ideas with other researchers on the project.” Another who developed “a strong international network with other researchers involved in long-term projects” encountered the challenge of “not being a co-author on papers which were almost entirely based on the data I generated”. It could be that collaboration and networking can lead to the stated challenges. For example, working in larger collaborative groups can lead to more interpersonal conflict (e.g., Müller 2012), project overlap among many students on the same long-term project, or issues with data when many people are contributing to the same dataset.

For the participants who identified an unexpected benefit related to skills, nine identified data as a challenge, followed by six with interpersonal or hierarchical conflict. The connection between skill development and encountering data challenges could be that overcoming data-related challenges necessitate technical skills development. For example, a participant who had the benefit of “being ‘gifted’ detailed and multi-year datasets” in turn “found [themselves] concerned with data quality”. Another possible connection may stem from participants valuing enhanced skills development above collaboration or networking. One participant felt “having to quickly get familiar on how to extract data and understand the whole process” was a benefit, yet found a challenge in “trying to understand how data was collected and processed in early years of the project”. Another found the existing database management and “transmission of information on the long term [project]” to be beneficial, but appeared frustrated by the “lack of automatic error checking, no shared R code”.

The difference in collaboration/interpersonal tendencies versus data-focused tendencies across questions may allude to different interests and values of graduate students coming into such projects, and perhaps different projects may attract or better serve different values. However, the degree of overlap among the benefits of collaboration, networking, and skills development with the challenges of interpersonal conflict and data could collectively be interpreted as a suite of characteristics of prevalent graduate student experiences in LTER projects. The framing of the questions leading to these responses as unexpected challenges and benefits is important to be mindful of here, especially in relation to existing data, researchers involved, and possible research questions to be investigated as motivators to join a LTER project (Fig. 1).

Study constraints and considerations

This study was designed to be exploratory in nature, casting a net for a range of respondents and investigating a wide scope in topics and questions, with the intention of identifying emerging categories and potential areas for improvement. We also aimed to center the experience of graduate students, both past and present. As such, we encourage our results to be interpreted as an important place from which to continue a conversation about the roles and responsibilities of participants in LTER, and how participation in LTER may be bolstered or hindered by current practices. While the survey received a relatively small number of responses, the emerging sentiments provide a valuable sketch of what researchers at the beginning of their careers are experiencing within well-established projects.

Looking forward, it is also important to consider the experiences and perspectives that are not included in this survey. The trade-off we faced between gathering more detailed participant data and the protection of participants, largely at a more vulnerable stage of their careers, meant that we were unable to explore the influence of demographics and/or identity on expressed graduate student experiences. The challenges faced by individuals in LTER frameworks may be further exacerbated for individuals in equity-seeking groups (Tseng et al. 2020; Duc Bo Massey et al. 2021). We encourage individuals involved in LTER projects, particularly those in leadership positions, to take steps to support safe and equitable research. For example, thoughts about gender breakdowns and mental health in LTER projects came out in the “Additional Comments” section of our survey:

“I encourage you to look at gender authorship breakdown as I suspect some LTERs are doing very poorly in this regard, despite, more or less, even ratios at the grad and tech level”.

“Perhaps not unexpected, but maintaining one's mental health can be particularly challenging in a remote environment in which you are expected (both explicitly and implicitly) to work long days, forgo regular days off, and constantly be positive/upbeat. Also, cabin fever is real, even when you spend all day in outdoor solitude”.

Without comparison to individuals in non-LTER programs, it is difficult to tease apart benefits and challenges that are unique to LTER, and what are typical of collaborative projects or even of graduate school in general. Indeed, some challenges acknowledged in discussions of LTER are not necessarily due to the structure of LTER projects themselves (e.g., fieldwork taking students away from campus; Swank et al. 2001). Administering this survey to graduate students of ecological projects that are not considered “long-term” could reveal many similarities to perspectives expressed here. Regardless of whether challenges are unique to LTER or shared with scientific endeavors beyond LTER, these experiences are clearly occurring within LTER projects. Our results inform our objectives to explore experiences within LTER projects and identify key areas of strengths and improvement, regardless of the specificity to LTER. In this framing, many of the results of this study will be highly informative for a suite of research projects beyond the disciplines of ecology, evolution, and conservation, and beyond the temporal restrictions of being “long-term”.

Recommendations

We recommend the following actionable items for consideration by PIs of LTER projects to ensure both the quality and efficiency of the project and that the next generation of researchers receive high caliber and enjoyable training experiences. We lead with interpersonal recommendations given the frequency of the collaboration/networking-interpersonal conflict benefit–challenge pairing identified above.

1.

Management and interpersonal relations

When possible, participants at all levels should take professional training in management, conflict resolution, and mentorship (see Hund et al. 2018). These skills are often learned “on the fly,” but science is inherently a human endeavor, and receiving training to develop these skills can help navigate highly collaborative projects with differing power dynamics across roles. Formal training for workplace (including field) safety and sexual harassment training that considers participant identities are also critical components for a safe and healthy work environment (e.g., Rudzki et al. 2022).

“Proper management is essential to creating a balanced workplace. I've worked on other LTER projects that were managed phenomenally and fewer people were burnt out, frustrated, or unpaid. The quality of the data was also much better”.

2.

Communication

Integral to all aspects of LTER, we recommend timely and regular communication be a top priority. Creating clear and equitable avenues for communication among all participants, especially across supervisor–student levels, is critical firstly for safety, but also for the integrity of data collection and the ethical dissemination of findings down the road. Open and honest communication about both the benefits and the challenges of conducting research in LTER projects can provide opportunities to minimize and/or mitigate negative outcomes.

“There are huge benefits and some major concerns, but it is probably that way anywhere - transparency and communication would help a lot, as with any scenario”.

3.

Data

Collect data using well-documented protocols and organize data in central, accessible formats with thorough metadata. Long-term projects may have a legacy of unclear internal practices from past years or decades that make contemporary solutions more challenging to implement, but with purpose and documentation it is never too late to improve processes. We recommend LTER researchers harness the existing and rich literature already out on proper data archiving (Mills et al. 2015), existing database structures (e.g., SPI-Birds, Culina et al. 2020), and data preservation (e.g., Bledsoe et al. 2022).

“LTER requires, in my opinion, hiring an employee to ensure homogenization of data, compilation, transmission of information…”.

4.

Authorship

Establish ethical, consistent, and transparent policies around authorship, especially on projects with several collaborators (e.g., Huang et al. 2020; Cooke et al. 2021). The collection of data included in a LTER dataset often involves many more people over many years than other scientific endeavors might, which can cause tension surrounding author inclusion. We suggest here that criteria for fair, equitable, and inclusive authorship be explicitly discussed and clearly communicated with all involved parties early on in LTER involvement.

“Even within a project, or a lab, authorship requirements are grey and not well documented - transparency and consistency would be nice, especially at the onset of a project”.

While the above recommendations may not seem novel, the true recommendation here is to prioritize these considerations preemptively. Open discussions on these topics, early and often, can ensure the myriad benefits persist (and even grow), while shrinking the negative effects.

Conclusion

Collectively, participants who conducted their graduate research in conjunction with a LTER project view the experience as positive. However, negative experiences referenced by some participants serve to identify aspects of project management that research leaders should prioritize to improve the experience of all participants, and aspets that prospective graduate students may want to consider more carefully when contemplating graduate programs. While there have been shifts in recent decades to begin to address issues related to mentorship (Hund et al. 2018), pedagogy (e.g., Tanner and Allen 2006), and inclusivity and diversity in the field (e.g., Tseng et al. 2020), academia still has many strides to make on these issues, and LTER projects that train graduate students should begin and/or continue to consider them explicitly.

Future work should build on the categories emergent from this study from perspectives of graduate students and of project PIs. For example, determining the extent to which the patterns reported here are attributable to individual student characteristics versus those of the projects will help better understand and serve graduate student interests, while also guiding PIs in focusing efforts on training and organizational protocols. Doing so will require expanding the sample population to reduce potential biases in our sampling methods (e.g., toward North American/European projects) and to acquire key attributes such as gender, nationality, etc. Furthermore, an explicit study of PI experiences would complement the current study, particularly to explore perceptions on how these projects are run from a leaders’ perspective. It may be that some of the benefits and challenges reported here by trainees are rooted in logistical and organizational challenges faced by the PIs themselves (e.g., stressors related to acquiring funding, students not publishing their work, among others). Such insights will help further guide actions and policies to help mitigate challenges and continue to enhance the training quality and other benefits of participation.

Long-term ecological research projects offer important opportunities for graduate-level training. We found general support among current and past graduate students for the touted benefits and identified challenges connected to data organization and navigating collaborative environments. The perceived value of LTER projects to the careers of early career scientists is significant, and highlights an avenue for future research to investigate the realized impacts on careers. Uptake of the recommendations offered here will ensure a more positive student experience, contributing not only to the success of the students, but, given the strong indication of desire to return to long-term research in the future, to the success and longevity of long-term research in this field.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jeff Bowman for invitations to join the ad-hoc steering committee for LTR-CSEE, and for co-chairing the Section’s inaugural symposium with AEW, as both opportunities encouraged the undertaking of this project. We thank Stan Yu for guidance in designing the survey and conducting ethical social science research. We thank Jeff Bowman, Landon Jones, Jared Elmore, Natasha Ellison, three anonymous reviewers, and the FACETS subject editor for constructive feedback that greatly improved the quality of this manuscript. There was no dedicated funding to report for this survey. AEW was personally supported during data collection and writing through the Teacher Scholar Doctoral Fellowship, a Mitacs Research Fellowship, a sessional lectureship, and graduate assistantship at the University of Saskatchewan, MRB through a postdoctoral fellowship at Mississippi State University, and AKM through a Liber Ero postdoctoral fellowship.

References

Armitage K.B. 1991. Social and population dynamics of yellow-bellied marmots: results from long-term research. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 22: 379–407.

Baker M. 2016. 1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility. Nature, 533: 452–454.

Bledsoe E.K., Burant J.B., Higino G.T., Roche D.G., Binning S.A., Finlay K., et al. 2022. Data rescue: saving environmental data frome extinction. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 289: 202209382.

Charmaz K. 2014. Constructing grounded theory. SAGE.

Clutton-Brock T., Sheldon B.C. 2010. Individuals and populations: the role of long-term, individual-based studies of animals in ecology and evolutionary biology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 25: 562–573.

Cooke S.J., Nguyen V.M., Young N., Reid A.J., Roche D.G., Bennett N.J., et al. 2021. Contemporary authorship guidelines fail to recognize diverse contributions in conservation science research. Ecological Solutions and Evidence, 2: 1–7.

Culina A., Adriaensen F., Bailey L.D.,Burgess M.D., Charmantier A.,Cole E.F., et al. 2020. Connecting the data landscape of long-term ecological studies: the SPI-Birds data hub. Journal of Animal Ecology, 90: 2147–2160.

Dantzer B., McAdam A.G., Humphries M.M., Lane J.E., Boutin S. 2020. Decoupling the effects of food and density on life-history plasticity of wild animals using field experiments: insights from the steward who sits in the shadow of its tail, the North American red squirrel. Journal of Animal Ecology, 89: 2397–2414.

Duc Bo Massey M., Arif S., Albury C., Cluney V.A. 2021. Ecology and evolutionary biology must elevate BIPOC scholars. Ecology Letters, 24: 913–919.

Evans S.R. 2016. Gauging the purported costs of public data archiving for long-term population studies. Plos Biology, 14: e1002432.

Evans T.M., Bira L., Gastelum J.B., Weiss L.T., Vanderford N.L. 2018. Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36: 282–284.

Gosz J.R., Waide R.B., Magnuson J.J. 2010. Twenty-eight years of the US-LTER program: experience, results, and research questions. In Long-term ecological research: between theory and application. Edited by F. Müller, C. Baessler, H. Schubert, S. Klotz. Springer.

Hampton S.E., Labou S.G. 2017. Careers in ecology: a fine-scale investigation of national data from the U.S. Survey of Doctorate Recipients. Ecosphere, 8: e02031.

Hay I. 2005. Qualitative research methods in human geography. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press.

Hobbie J.E., Carpenter S.R., Grimm N.B., Gosz J.R., Seastedt T.R. 2003. The US Long Term Ecological Research Program. Bioscience, 53: 21–32.

Huang T.Y., Downs M.R., Ma J., Zhao B. 2020. Collaboration across time and space in the LTER Network. Bioscience, 70: 353–364.

Hughes B.B., et al. 2017. Long-term studies contribute disproportionately to ecology and policy. Bioscience, 67: 271–278.

Hund A.K., Churchill A.C., Faist A.M., Havrilla C.A., Love Stowell S.M., McCreery H.F., et al. 2018. Transforming mentorship in STEM by training scientists to be better leaders. Ecology and Evolution, 8: 9962–9974.

Krebs C.J. 1991. The experimental paradigm and long-term population studies. IBIS, 133: 3–8.

Kuebbing S.E., Reimer A.P., Rosenthal S.A., Feinberg G., Leiserowitz A., Lau J.A., Bradford M.A. 2018. Long-term research in ecology and evolution: a survey of challenges and opportunities. Ecological Monographs, 88: 245–258.

Lack D. 1964. A long-term study of the great tit (Parus major). The Journal of Animal Ecology, 33: 159–173.

Leon-Beck M., Dodick J. 2012. Exposing the challenges and coping strategies of field-ecology graduate students. International Journal of Science Education, 34: 2455–2481.

Lindenmayer D.B., Likens G.E., Andersen E., Bowman D., Bull C.M., Burns E., et al., 2012. Value of long-term ecological studies. Austral Ecology, 37: 745–757.

Mills J.A., Teplitsky C., Arroyo B., Charmantier A., Becker P.H., Birkhead T.R., et al., 2015. Archiving primary data: solutions for long-term studies. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30: 581–589.

Müller R. 2012. Collaborating in life science research groups: the question of authorship. Higher Education Policy, 25: 289–311.

Newing H. 2011. Conducting research in conservation: social science methods and practice. Routledge.

Pace M.L., Carpenter S.R., Wilkinson G.M. 2019. Long-term studies and reproducibility: lessons from whole-lake experiments. Limnology & Oceanography, 64: S22–S33.

Romolini M., Record S., Garvoille R., Marusenko Y., Geiger S. 2013. The next generation of scientists: examining the experiences of graduate students in network-level social-ecological science. Ecology & Society, 18.

Rudzki E.N., Kuebbing S.E., Clark D.R., Gharaibeh B., Janecka M.J., Kramp R., et al. 2022. A guide for developing a field research safety manual that explicitly considers risks for marginalized identities in the sciences. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 13: 2318.

Sandelowski M. 1998. Writing a good read: strategies for re-presenting qualitative data. Research in Nursing & Health 21: 375–382.

Swank W.T., Meyer J.L., Crossley D.A. 2001. Long-term ecological research: Coweeta history and perspectives. In Holistic science: the evolution of the Georgia Institute of Ecology (1940–2000). Edited by G.W. Barrett, T.L. Barrett. Sheridan Books. pp 143–163.

Tanner K., Allen D. 2006. Approaches to biology teaching and learning: on integrating pedagogical training into the graduate experiences of future science faculty. Life Sciences Education, 5: 1–6.

Tinkle D.W. 1979. Long-term field studies. Bioscience, 29: 717.

Tseng M., El-Sabaawi R.W., Kantar M.B., Pantel J.H., Srivastava D.S., Ware J.L. 2020. Strategies and support for Black, Indigenous, and people of colour in ecology and evolutionary biology. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4: 1288–1290.

Tuma T.T., Adams J.D., Hultquist B.C., Dolan EL. 2021. The dark side of development: a systems characterization of the negative mentoring experiences of doctoral students. Life Sciences Education, 20.

Vanderbilt K.L., Lin C.C., Lu S.S., Kassim A.R., He H., Guo X., et al. 2015. Fostering ecological data sharing: collaborations in the International Long Term Ecological Research Network. Ecosphere, 6: 1–18.

Vucetich J.A., Nelson M.P., Bruskotter J.T. 2020. What drives declining support for long-term ecological research? Bioscience, 70: 168–173.

Waide R.B., Kingsland S.E. (Editors). 2021. The challenges of long term ecological research: a historical analysis. Springer.

Wallis J.C., Borgman C.L. 2011. Who is responsible for data? An exploratory study of data authorship, ownership, and responsibility. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 48(1): 1–10.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Material 1 (DOCX / 12.2 KB).

- Download

- 12.21 KB

Supplementary Material 2 (DOCX / 11.1 KB).

- Download

- 11.11 KB

Supplementary Material 3 (DOCX / 20.8 KB).

- Download

- 20.80 KB

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

FACETS

Volume 9 • 2024

Pages: 1 - 12

Editor: Marie-Claire Shanahan

History

Received: 17 March 2023

Accepted: 7 December 2023

Version of record online: 28 March 2024

Notes

Study protocols and survey materials were approved by the University of Saskatchewan Behavioural Research Ethics Board (BEH-1283).

Copyright

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Data Availability Statement

Data requests should be directed to the University of Saskatchewan Behavioural Research Ethics Board reachable by email ([email protected]) citing the approval ID (BEH-1283).

Key Words

Sections

Subjects

Plain Language Summary

Experiencing long-term ecological research projects as a graduate student: benefits and challenges

Authors

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AEW

Data curation: AEW

Formal analysis: AEW, MRB, AKM

Investigation: AEW, MRB, AKM

Methodology: AEW, MRB

Project administration: AEW

Visualization: MRB

Writing – original draft: AEW, MRB, AKM

Writing – review & editing: AEW, MRB, AKM

Competing Interests

AEW was, at the time of writing, a PhD student associated with the Kluane Red Squirrel Project. MRB was a PhD student associated with the Kluane hare-lynx project. AKM was a PhD student on both aforementioned projects. All authors have benefited from these projects’ long-term data for publication. This manuscript was conducted independently from both projects and without input from its associates. AEW was a student bursary recipient at the LTR symposium held in 2017. As of writing, AEW was the first and only graduate student member, while MRB was the first postdoctoral member of the LTR-CSEE advisory committee. MRB and AKM had completed the survey prior to onboarding as authors (onboarding occurred 2 years after data collection), but fully anonymized responses prevented removal of their comments. AEW is at the time of submission an employee of Canadian Science Publishing, publisher of FACETS. None of the authors involved in the manuscript were involved in the peer-review process, nor is there any formal reporting relationship whereby one of the co-authors supervises or is supervised by any of the editorial team that handled the manuscript.

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Other Metrics

Citations

Cite As

Andrea E. Wishart, Melanie R. Boudreau, and Allyson K. Menzies. 2024. Graduate student experiences and perspectives related to conducting thesis research within long-term ecological projects. FACETS.

9: 1-12.

https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2023-0041

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

Cited by

1. Long‐term studies should provide structure for inclusive education and professional development