Assessing species at risk legislation across Canadian provinces and territories

Abstract

Introduction

Methods

Results

British columbia

Listing process

Species and habitat protection

Recovery

Updates

Alberta

Listing process

Species and habitat protection

Recovery

Updates

Saskatchewan

Listing process

Species and habitat protection

Recovery

Updates

Manitoba

Listing process

Species and habitat protection

Recovery

Updates

Ontario

Listing process

Species and habitat protection

Recovery

Updates

Québec

Listing process

Species and habitat protection

Recovery

Updates

Newfoundland and labrador

Listing process

Species and habitat protection

Recovery

Updates

New brunswick

Listing process

Species and habitat protection

Recovery

Updates

Prince Edward Island

Listing process

Species and habitat protection

Recovery

Updates

Nova Scotia

Listing process

Species and habitat protection

Recovery

Updates

Territories

Yukon

Listing process

Species and habitat protection

Recovery

Updates

Northwest territories

Listing process

Species and habitat protection

Recovery

Updates

Nunavut

Listing process

Species and habitat protection

Recovery

Updates

Recommendations

Pursue dedicated and harmonized species at risk legislation

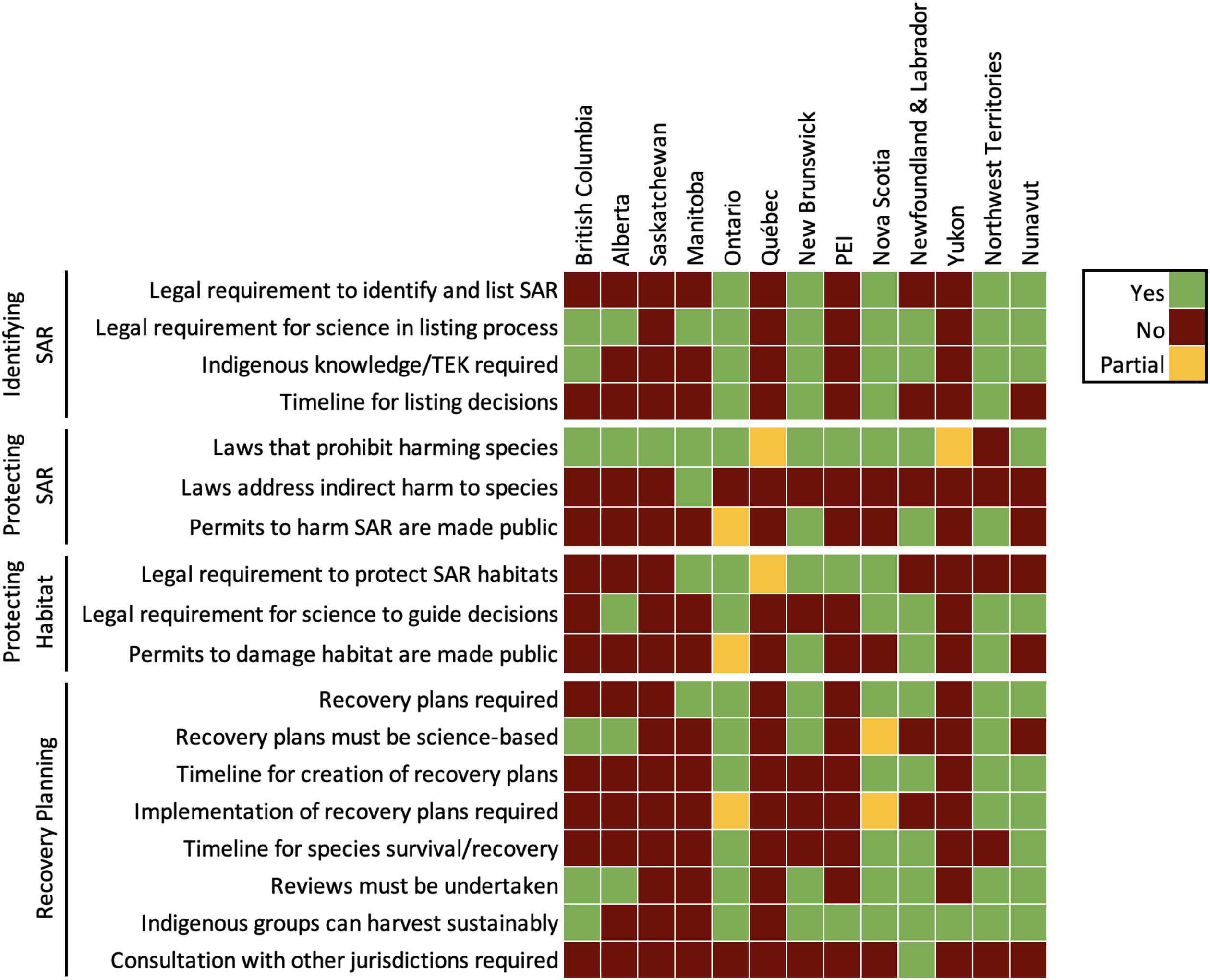

| Problem | Most affected provinces/territories | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Species at risk regulations are dispersed among multiple acts or in acts dedicated to hunting or wildlife management | British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Québec, PEI, Yukon, Nunavut | (1) Establish dedicated species at risk legislation encompassing all relevant taxa |

| Final listing decisions are not made by independent experts or are influenced by discretionary power | British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Québec, Newfoundland and Labrador, PEI, Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut | (3) Establish a fully independent committee responsible for assessing species at risk (5) Appoint members with scientific, Indigenous and traditional knowledge (2) Automatically designate species following committee recommendations and Indigenous consultation |

| Species protection and/or recovery plans are not required or are subject to discretion | British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Québec, Newfoundland and Labrador, PEI, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Yukon, Northwest Territories | (6) Establish automatic prohibitions against harming listed species and their critical habitat (2) Establish recovery plan requirements for listed species |

| Timelines are not present or are not enforced (assessed only for provinces with dedicated SAR legislation) | Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Northwest Territories | (4) Establish enforceable timelines for key steps in the listing and recovery process for SAR (5) Limit exceptions for extensions |

| Exemptions and permits compromise species and habitat protection | British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Québec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Northwest Territories, Nunavut | (5) Eliminate the use of “conservation funds” for granting exemptions (5) Limit exemptions to activities that will not place species further at risk(3) Prioritize Indigenous rights to manage their traditional territories and the species within them, and explore co-management where appropriate |

| Habitat protection is limited to public land | British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, PEI, Yukon | (3) Identify critical habitat of SAR(6) Automatically protect critical habitat on public and private land(6) Encourage partnership with landowners by providing compensation and conservation incentives |

| Listing process and recovery plans are not made publicly available or are not open to public comment (assessed only for provinces with dedicated SAR legislation) | Manitoba, Québec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia | (7) Establish a publicly accessible website with information on assessment committees, listing process, listed species, permits, and recovery plans(7) Provide an opportunity for public comment on recovery plans |

Note: Note that we consider written law only, and do not consider implementation. The numbers in brackets refer to the corresponding recommendation section in the text.

Reduce reliance on discretionary power

Embrace Western science and Indigenous rights, science, and evidence

Establish reasonable timelines

Restrict and regulate exemptions

Protect habitat on government and private lands

Commit to transparent decision-making

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Copyright

Data Availability Statement

Key Words

Sections

Subjects

Authors

Author Contributions

Competing Interests

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Other Metrics

Citations

Cite As

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.