Our purpose in sharing this story

The formation of the Atlantic First Nations Water Authority (AFNWA) established the first Indigenous-owned and operated water and wastewater utility in Canada, currently providing services to 12 participating First Nations. The AFNWA represents an important change in the way water services are provided to First Nations. The story of the AFNWA is one of Chiefs, Elders, and community members building their own water utility to ensure safe drinking water and clean wastewater for their communities. The formation and operation of the AFNWA is guided by Two-Eyed Seeing (translated in Mi’kmaq as Etuaptmumk) principles to deliver services in ways that honour and celebrate First Nations world views and ways of knowing. We aim to tell part of the AFNWA story to share our experiences with Two-Eyed Seeing and show others how First Nations knowledge and culture can join alongside western technical practices to build Indigenous-led utilities.

The practice of Two-Eyed Seeing is to recognize that different ways of knowing and different values can be brought together to find solutions to problems and build paths together. However, learning how to meaningfully bring Two-Eyed Seeing into an engineering context requires listening and learning between First Nations people western-based engineers.

“Etuaptmumk (Two-Eyed Seeing) isn’t that well known in Engineering. It started in the Social Sciences. We may have to do an Etuaptmumk 101 for Engineers.” Tuma Young

Two-Eyed Seeing is a way of recognizing Indigenous and western knowledge and ways of knowing, first described by Elder Albert Marshall (

Bartlett et al. 2012). It is often explained as taking the best that Indigenous knowledge systems have to offer and the best that western knowledge systems have to offer and using them together to find solutions to problems, conduct research, and learn about our relationship with our surroundings.

“Etoi – is a prefix that means equal, it can be used to mean a person is ambidextrous (etoiptinan), they can use their left and right hands equally well. Or when you’re sitting next to your partner – you’re equal in how you perceive things” Ken Francis

The AFNWA acknowledges people’s relationship with water and understands the importance of protecting the water for future generations. This paper offers a perspective for blending technical knowledge of engineering decision-making in water with knowledge from Wabanaki elders concerning water that has guided a Two-Eyed Seeing approach embodied by the AFNWA.

Indigenous methodologies and ways of knowing

There are Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqey words used throughout, to communicate important cultural concepts and ideals. There is a glossary of terms in the Appendix A1.

Elders Advisory Lodge meetings and Knowledge Sharing

The authors of this paper include First Nations Elders and knowledge keepers from the Elders Advisory Lodge (EAL) of the AFNWA, Indigenous and non-Indigenous staff from the AFWNA, and non-Indigenous researchers and faculty from Dalhousie University’s Centre for Water Resources Studies (CWRS). We chose to tell this story to both First Nations and western engineering audiences by sharing direct quotes from the members of the EAL because storytelling and talking with Elders play important roles in constructing and passing down Indigenous knowledge, ways of learning about the world, and understanding our relationship to Mother Earth and each other. The majority of the conversations and knowledge sharing took place from January 2022 to March 2024 during quarterly meetings of the EAL. The Lodge is composed of Elders from First Nations that own and operate the AFNWA, including the EAL Chair Mathilda Knockwood Snache from Lennox Island First Nation, Dr. David Perley from Neqotkuk First Nation, Ken Francis from Elsipogtog First Nation, Gail Tupper from Glooscap First Nation, Charles Doucette from Potlotek First Nation, and the EAL facilitator Tuma Young from Eskasoni First Nation. Quotes taken from recordings of EAL meetings are included in this work and are attributed to EAL members and other authors. This work does not require research ethics approval, as no research was done on human subjects.

Talking Circle and Knowledge Sharing

In addition to stories and ideas gathered from EAL meetings, this paper draws on knowledge shared at a talking circle facilitated by the Atlantic Policy Congress of First Nations Chiefs Secretariat (APCFNC) in 2017 where Elders, knowledge keepers, and community members came together to inform the development of the AFNWA. Quotes and ideas shared during this public forum are included in this work, because they represent guiding ideals central to the AFNWA. These quotes are presented here without attribution, as they were initially recorded anonymously, and are referred to as “community engagement sharing circle”. The AFNWA provided the report from the talking circle to contribute to this work (

APC 2017).

The members of the EAL value storytelling and talking circles as ways of sharing and validating knowledge.

“Sharing knowledge means protecting it. If you don’t share it, it’s in danger of being lost.” Tuma Young

“This is how our hearts meet each other. We know what we’re talking about. But if there was a western person sitting there, would they understand us? And I think that's our job. That before we leave this planet Earth, we share these things.” Methilda Knockwood Snache

“As a western researcher, I think of knowledge as a collection of facts - objective and observable. Working with the Elders Advisory Lodge has taught me that knowledge doesn’t stand alone, it is relational, it is experienced, and it is personal.” Megan Fuller

Sharing and legitimizing Knowledge

This is an article rooted in describing Two-Eyed Seeing in the context of a water utility, meant to provide examples of how to operationalize Two-Eyed Seeing and value Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing in the field of engineering. The methods used in this paper for acquiring and presenting ideas and knowledge also attempt to use Two-Eyed Seeing. The authors understand the western practice of using peer-review publication and citation as one way of legitimizing information and crediting others for their thoughts and knowledge. However, the majority of the authors of this paper are First Nations people, who do not use citation of past publications to validate their knowledge. To honour both the western and Indigenous ways of legitimizing knowledge, limited citations are provided throughout to help the reader find other resources but most of the knowledge is shared as a narrative grounded in the experience and knowledge of the Elders.

“We are writing this for our people too” Methilda Knockwood Snache

“The only source I have to cite is my father, and he would cite his father. The way we would “cite” our knowledge would be to check with the Elders” Ken Francis

The need for a return to First Nations values in water service provision

The path from first contact, signing of treaties, colonial transgression of treaties, creation of the Indian Act, and the dispossession of First Nations lands and territories is a long and complex history that has shaped the current landscape, both physically and politically. While this context is crucial for understanding how First Nations came to suffer inequitable services and inadequate drinking water and wastewater systems, a meaningful introduction to this topic is beyond the scope of this paper and not the intention of the Elders and authors. We suggest the reader use other sources (See a list of references selected by EAL members for additional reading in Appendix A2) to familiarize themselves with this history to more fully understand how First Nations were relegated to Reserve land (land set aside by the government for the use of an “Indian” band), further displaced by the failed Centralization effort of the 1940’s, and forced into poverty conditions through the disruption of traditional resource distribution and implementation of insufficient federal funding schemes (as told by Elders in the Lodge and stories they have heard themselves, Knockwood Snache, M., Francis, K., Young, T., Perley, D. Neqotkuk (personal communication, January 2022–March 2024);

Hurley and Wherrett 2000).

The Constitution of Canada devolves the responsibility of drinking water and wastewater services to the Provinces and Territories, including evaluation and enforcement of standards. This creates a significant governance and regulatory gap for First Nations communities located on federal lands. While there are limited pieces of legislation that regulate water bodies, i.e., the Fisheries Act and the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, there are currently no legislated drinking water quality standards for First Nations. The funding for critical infrastructure, operation, and maintenance of drinking and wastewater facilities, and investment in capital projects is largely determined by Indigenous Services Canada (ISC). A Report on Access to Safe Drinking Water in First Nations Communities prepared by the Office of the Auditor General (OAG) released in 2021 notes that efforts to remove long-term drinking water advisories in First Nations communities were insufficient and that ISC was using an outdated policy and formula for funding the operation and maintenance of the water systems (

OAG 2021). The report concludes that lasting solutions will only be possible if reached in partnership with First Nations. This is the third report on safe drinking water in First Nations communities issued by the OAG. The first two reports were issued in 2005 and 2011 and document key gaps and recommendations to address safe drinking water for First Nations.

The

OAG (2021) report states that ISC is “aware that new approaches are needed in terms of funding the operations and maintenance of infrastructure on reserve”. ISC recognizes that there is a need for predictable funding that will support strategic decision-making built on detailed asset information. While most First Nations and the Assembly of First Nations are trying to navigate improved funding and management models with ISC, the Chiefs in the Atlantic Region have led the way on building a new path for First Nations service delivery through self-determination, specifically through self-determined Indigenous governance and values (

M'sɨt No'kmaq 2021).

The AFNWA was formed through years of community engagement, First Nations leadership, and progressive policy development led by the APCFNC. The APCFNC is a policy research and advocacy Secretariat for 33 Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqey (Maliseet), Passamaquoddy and Innu Chiefs, Nations, and communities. The APCFNC recognized that the long-standing deficiencies in centralized water and wastewater services are a complex tangle of inadequate funding, fragmented federal management, and diminished First Nations agency, all compounded by the absence of regulations enacting treatment, monitoring, and water quality standards. Those involved in developing a First Nations solution to this multitude of challenges understood that long-range funding, consolidated management, and binding standards would be needed to achieve safe and sustainable water services to protect public and environmental health. Most importantly, the APCFNC understood that any effective solution must be owned by First Nations and grounded in First Nations culture and values to address the needs and rights of First Nations people to have safe drinking water and clean wastewater.

The APCFNC engaged both First Nations and non-First Nations knowledge holders during the planning, design, and incorporation of the AFNWA. Chiefs, Elders, water protectors, knowledge keepers, engineering firms, municipal water utilities, business development consultants, lawyers, and academic institutions all worked together to imagine a new paradigm for First Nations water services (

Gould 2022). The purpose of this article is to tell some of the story of the formation of the AFNWA, and most importantly to tell the story of how Indigenous and non-Indigenous people worked to bring their different ways of knowing together through Two-Eyed Seeing to find a solution to a persistent harm caused by historical and ongoing colonialism.

A water utility for First Nations, by First Nations

The AFNWA was incorporated under the Canada Not-for-Profit Act in 2018 as the only Indigenous-owned and operated water utility in Canada. The incorporation marked a significant turning point in a more than decade-long journey to develop a First Nations-led solution to address the persistent inequities that exist in water service provision in First Nation communities. The AFNWA assumed authority and responsibility for water services (drinking water and wastewater) in participating First Nations in early 2023 and continues to work with additional Nations interested in joining the organization. The transfer of assets, operations, funding, and liability to a First Nations organization and away from the Federal Government is a significant step toward self-determination and a fundamental change in the colonial, paternalistic management structures that persist in Canada–Indigenous relationships. The AFNWA is owned and operated by the 12 participating First Nations located in the Mi'kmaq and Wolastoqey Nations, in the Wabanaki Territory (Wabanki translates to the People of the Dawn) where Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island are located.

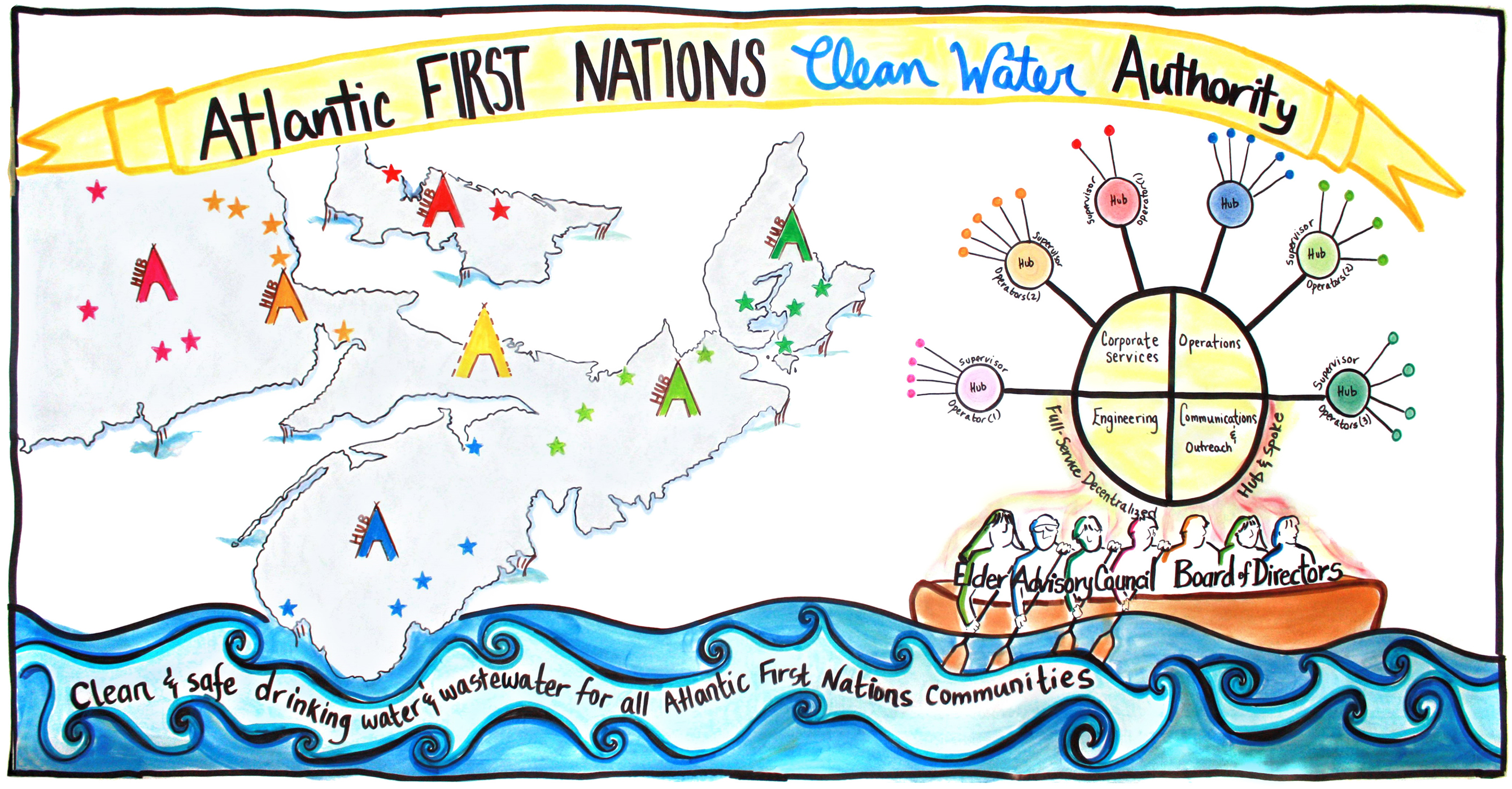

To ensure participating Atlantic First Nations receive the level of service required to meet the water authorities’ objectives, the AFNWA operations is structured as a full-service, decentralized utility (FSD), or “hub and spoke” model. Under this organizational design, service delivery is arranged into a network of several geographic hubs that offer an array of services to the First Nations (spokes).

Figure 1 shows a graphical representation of the AFNWA’s hub and spoke model. This image was made by a graphic recorder during a 2018 engagement session held by the APCFNC to design a service model for the AFNWA and is now the utility’s pictural representation of its service areas located across the Atlantic region. The image shows colourful wigwams representing the service area hubs distributed across the provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward’s Island.

Under the hub and spoke model, local community-based operations staff are organized around the following geographic areas:

•

We’kopekwitk (Eastern Nova Scotia)

•

Kespukwitk (Western Nova Scotia)

•

Mlsigeneegatig (Eastern New Brunswick)

•

Wolastokuk (Western New Brunswick)

•

Epekwitk (Prince Edward Island)

The FSD model accommodates varying circumstances such as growing or declining populations or changing (geographic) groupings of participating First Nations. Additionally, the hub and spoke allows the AFNWA to recognize First Nations’ traditional territory and Atlantic Canada’s geographic challenges by optimizing service delivery with communities being no more than a 2.5 h drive away from a service hub

Locating hubs within the communities allows the AFNWA to position expertise and operational knowledge close to water and wastewater systems while providing support from the main office and regional hubs.

Structuring the AFNWA under the FSD model allows for the most effective and efficient operation coupled with the best opportunity to foster relationships with the participating First Nations and work closely with the First Nations to build capacity for sustainable water services. This relationship is important to ensure traditional knowledge and values are integrated into how the AFNWA operates.

Wabanaki people have a fundamentally different relationship with Earth, its animals, plants, air, and water than most western people experience. They have a profoundly different understanding of their responsibilities to Earth and all of their relations, built on reciprocity and respect.

“My Elder has told me stories of when he was young, his father would take him out of Indian Day School to learn from the land. He said if he took a plant for medicine, his father taught him to offer tobacco to give thanks, to talk to the plant to acknowledge the spirit of the plant. This is something you will never see in the western ways of doing things.” David Perley

During the creation of the AFWNA, First Nations knowledge keepers, Elders, and Chiefs worked to ensure that the form and function of a First Nations water utility would not just be a copy of a western water utility. Since the creation of the reserve system and policy of centralization that moved First Nations people from their land, the provision of services has been delivered by the Federal Government of Canada. The bureaucratic approach to resource management has led to the removal of spirit, ceremony, and honouring of Mother Earth from the everyday interactions with water needed for sustenance and cleaning.

To ensure that the AFNWA is guided by the Wabanaki worldview and reflects the Mi'kmaq and Wolastoqey values and teachings, the organization worked closely with Chiefs and Councils of interested First Nations and held a series of engagement sessions from 2016 to 2018 to identify these core values and teachings and develop actions, functions, and organizational structures to embed these values in the organization. A key engagement session “Creating an Atlantic First Nations Water Authority with Culture as a Foundation: Elder Engagement” was held in March 2017 and brought together seven First Nations knowledge holders and Elders. The objectives of the engagement session were to understand the cultural and spiritual significance of water, identify core values of the AFNWA and link them to actions, share the purpose of a First Nations-owned water authority, and identify core elements of decision-making, communication, and an organizing structure that would respect First Nations values and communities. The Elders engagement session resulted in the identification of key values, decision-making practices, and organizational elements that were woven into the AFNWA’s business case, mission statement, and operation of the utility (

APC 2017).

Two-Eyed Seeing in practice

Many First Nations in Canada have a lived experience of unsafe water, frequent drinking water advisories, and in some cases years-long “do not consume” advisories. This collective burden has eroded trust in water and is contrary to the sacred relationship between First Nations people and water. During the engagement session to develop the concept of the AFNWA participants shared these thoughts (

APC 2017):

“Water quality is important. Technology can be used to remediate water and clean it. Science won’t save us.”

“Two-Eyed Seeing is needed to integrate Indigenous knowledge and Western science. This will help us undo some of the harm that has been created.”

There was a recognition that a purely western approach to a utility that used only science and engineering to provide water services would fail to recognize the sacred relationship with water that is central to First Nations’ natural laws. A return to, and celebration of, Indigenous values and culture was required for the AFNWA to fulfil its mission as a trusted First Nations partner. Self-determination and Indigenous ways of knowing and being in balance with Mother Earth are imperative to ensure safe drinking water and clean wastewater in First Nations communities and future generations. The AFNWA was formed to help address this broken trust and ensure Indigenous and non-Indigenous water stewardship knowledge was used together to uphold First Nations’ responsibility to take care of water and steward the health of Mother Earth.

Two-Eyed Seeing was proposed as a guiding principle for the AFNWA to help reconcile water quality, science, culture, and caring for youth and future generations. Those present at the 2017 community engagement talking circle shared (

APC 2017)

“…we can demonstrate Two-Eyed Seeing. We have to restore our relationship between communities and water. We need to reconnect people to the source of water and importance of it. They have a lack of trust in water.”

The AFNWA has woven Two-Eyed Seeing into organizational, capacity-building, and governance elements that are central to the organization, to ensure the best of the western systems and Indigenous systems are brought together to guide the utility.

“It was told to me that a system is automatically made better when you own it. The AFNWA is about taking responsibility out of the hand of the Federal Government and into First Nations. This was achieved when the Service Delivery Transfer Agreement was signed with Minister Patty Hajdu” James MacKinnon

Organizational structure—Elders Advisory Lodge (EAL)

The most important commitment the AFNWA has made to ensure Two-Eyed Seeing guides the utility in its operation and function is through the creation of the EAL. Elders play a crucial role in First Nation communities and are keepers of traditional knowledge and culture. To ensure the AFNWA is and remains aligned with First Nations values, culture, and knowledge, the Corporate Governance Manual sets out the creation of the EAL as an ex officio advisory committee through which community Elders provide advice to the Board. The EAL is a group of Elders and a designated facilitator that sits adjacent to the Board of Directors. The members were nominated by Chiefs and community leaders because of their knowledge of Mi'kmaq and Wolastoqey histories and ways of knowing, as well as their relationships to water and stewardship. Each Elder chose to accept their position on the Lodge for specific reasons, called to this work to protect and celebrate water and share cultural teachings and values.

The EAL has the following roles and responsibilities:

•

Inform the Board on issues of community and cultural importance

•

Advise on the overall strategy and direction of the AFNWA to ensure it remains aligned with First Nations values, culture, and knowledge

•

Inform the AFNWA of any cultural interests and concerns of the First Nations Communities served by the AFNWA

•

Provide guidance on any matter within their experience when asked to do so by the Chair of the Board

•

At the discretion of the Chair of the Board of Directors, Elders may be asked to speak to media regarding cultural and spiritual matters related to the AFNWA

•

Elders Advisory Lodge has the obligation to participate in presentations and to share Wabanaki knowledge

“Knowing the language and using the language, I have convictions in me, I have knowledge in me, I have a lot of decision-making ability in me simply because I have knowledge of the Mi'kmaq language.” Ken Francis

“We as kids would go back to the natural springs with plastic jugs every couple of days to get water. I showed them where the water came from. Its good to relive it. This traditional knowledge is in each of us, even if we don’t know it.” Gail Tupper

“This speaks to why Elders agreed to join the Elders Advisory Lodge. We don’t want to lose our culture, traditions, and stories. We don’t want to lose the past. It was the way we were brought up, our teachings, our cultures, our traditions. As an Elder on the Advisory Lodge, I don’t want to see this lost.” Methilda Knockwood Snache

“Building these relationships with elders gives us guidance. This is a need for Indigenous staff to feel the connection and welcomed in the space. This is important for youth/ younger generations within the field.” Tiannie Paul

Relationship building

The AFNWA works to ensure it brings Two-Eyed Seeing principles to both its external relationships and the internal staff relationships. Atlantic First Nations people have a fundamentally different understanding of their relationship with the world than most western cultures. Msit No'kmaq (Mi’kmaq) or Psiw Ntolnapemok (Wolastoqey) translates to “all my relations” and reflects the belief that First Nations people are in relationships to all things on earth, all of creation.

“I’ve heard that engineers need to build relationships with First Nations clients, but what does that mean? What does that look like? My time talking with First Nations operators, community staff, and Elders have helped me understand that listening and sharing help me better understand what’s important to First Nations community members and their priorities guide my work.” Megan Fuller

Kerry Prosper, a Mi'kmaq Elder, writes of netukulimk as a “culturally rooted concept [that] operates as a guide to responsible co-existence and interdependence with natural resources, each other and other than human entities. It is considered as a body of living knowledge, which underpins the moral and ethical relationships that explains their world in the past and provides for the present by sustaining the future.” (

Prosper et al. 2011).

These relationships have inherent responsibilities and obligations, guided by natural laws and Grandfather Teachings. To embrace and reflect the moral and ethical relationships with the work, the AFNWA adopted the 7 Grandfather Teachings as their corporate values to guide their service to their communities.

They are

•

Love (Kitpu/Cihpolakon—Eagle)

•

Honesty (Putup/Putep—Whale)

•

Humility (Paqtism/Malsom—Wolf)

•

Truth (Mikjikj/Cihkonaqc—Turtle)

•

Bravery (Muin/Muwin—Bear)

•

Wisdom (Kopit/Qapit—Beaver)

The AFNWA is continuously working to strengthen its relationships both within the organization and beyond with participating First Nations, stakeholders, engineering firms, academic institutions, other First Nations organizations, and those brought in to serve the communities directly. This relationship building is centred on communicating First Nations values and ensuring the cultural significance of netukulimk and msit No'kmaq are reflected in the day-to-day operations of the AFNWA, guided by the 7 Grandfather Teachings.

Actions to build relationships

Contractor meetings

The AFNWA recognizes there is a significant need for infrastructure upgrades in participating communities, and routine and emergent maintenance needs will require trusted contractors and service providers. These relationships with engineering firms, consultants, contractors, and service providers are critical to the Authority’s success. The AFNWA developed a practice of engaging with potential third-party service providers through regional workshops for construction, IT, engineering, and technology firms to share the mission and values of the AFNWA. Participants are invited from across the Wabanaki territory and dozens of industry representatives have joined in these workshops to learn about the AFNWA’s commitment to safety and hear about the upcoming capital projects and operational programs under development with the AFNWA and participating communities. The workshops are designed to allow for a lengthy question and answer period over lunch, to foster conversation and allow AFNWA staff and attendees to get to know each other. The purpose of the workshops is to begin building relationships with service providers and contractors based on sharing and listening. Many third-party service providers are non-Indigenous and may have limited experience working with, and for, First Nations. The AFNWA uses these workshops as a forum to discuss the cultural significance of water and the uniqueness of the AFNWA as a First Nations water utility.

“That is Two-Eyed Seeing. Nobody understands each other. So there has to be a common ground, somewhere you begin to explain. There is so much knowledge out there, but it’s how you ask the questions.” Methilda Knockwood-Snache

“Non-Indigenous Engineers don’t immediately understand the importance of relationships and relationship building when they go in to work with communities. Until I sat down with the Elders and listened and learned from you for over a year, I didn’t really understand it. That is Etuaptmumk to me – to be able to talk to one another and listen to one another and be able to share all of our knowledge.” Megan Fuller

“I find in groups, introductions don’t need to happen. If you just keep talking, they will eventually get to know you.” Ken Francis

Operator workshops

The AFNWA recognizes that the collective organization of First Nations builds relationships, strengthens resiliency, and supports self-determination. Historically, the water operators for individual First Nations have little cause or opportunity to meet and share knowledge. The AFNWA was initially created to bring operators together under one organization to allow for cross-training and collaboration between operators. When a First Nation chooses to join the AFNWA, all current operators are offered employment with the utility. Since 2020, the AFNWA has held quarterly operator workshops to bring people together (virtually during COVID) to build relationships, get to know each other, and learn from each other. These quarterly workshops provide training on key treatment, operations, and administrative topics, but more importantly offer the operators a chance to discuss challenges, solutions, and shared experiences. They also provide an opportunity for management staff a chance to get to spend time in person with operators who work on-site in their communities. The more opportunities to have meals together, socialize, and work together the stronger their relationships become. Sharing experiences and telling stories about successes and challenges are important ways of learning and allow Indigenous ways of knowing and learning to strengthen the utility’s collective knowledge. How we ask questions of one another and how we listen guides us on the path to Two-Eyed Seeing.

“What do you know? Because of the history and trauma of colonization, they may not value their own knowledge. But if you ask them what they remember and recall they will be able to tell you more.” Tuma Young

“Wabanaki knowledge changes based on observations by each succeeding generation.” David Perley

“Indigenous knowledge isn’t static. It moves and changes just like water.” Tuma Young

These operator workshops are opportunities to continue to grow operators’ Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing.

Elders and cultural training

Another way the AFNWA brings Two-Eyed Seeing to the day-to-day operations of the utility is through ongoing cultural training to ensure both non-Indigenous and Indigenous employees are continuously learning about the communities they serve.

“Cultural training helps us learn about Indigenous culture – how do we bring it forward so it can be useful and meaningful to our communities.” Tuma Young

“People who come to work with us should understand why we do the things we do, to make sure they are knowledgeable about our relationship with water.” Methilda Knockwood Snache

“A Mi’kmaq Elder from Elsipogtog, Andrea Colfer, told us that for us to have unity and a balanced environment, we have to recognize the rivers as our great grandmothers, because when you look at Wolastoq (Saint John River) as great grandmother your relationship to the river will change.” David Perley

“We are always learning. There are many different kinds of culture in our communities. It’s not a monolithic thing. Culture is not static, it changes.” Tuma Young

The Cultural training activities have taken many forms since the formation of the AFNWA. One example of a cultural training event was a sharing circle for all AFNWA Headquarters staff, led by the Chair of the EAL, Methilda Knockwood Snache from Lennox Island First Nation and EAL member Charles Doucette from Potlotek First Nation. The directors of Engineering and Operations, as well as the Superintendent of Technical Services and Superintendent of Operations, were joined by the Finance department, administrative assistants, IT department staff, and other AFNWA staff to participate in the sharing circle and learn from the Elders and each other.

“We left the group thinking everybody’s on the right road. It’s about being a guide to our workers and young people.” Methilda Knockwood Snache

Cultural trainings are co-developed by the Manager of Communications and Outreach and the EAL to ensure all AFNWA employees are aware of the history of colonization, the culture of the communities they serve across the Wabanaki Territory, and the value and spiritual importance of water to the First Nations.

Cultural trainings offer a chance for everyone to come together and listen and learn. It may not be immediately relevant or directly related to the day-to-day operations of the AFNWA, but seeds may be planted that will positively benefit communities.

“Some of the stuff I know I was told when I was 5, 6, 7 years old, but I didn’t know or understand what they were saying. But when you’re older it clicks. And you know. You might be only half listening right now, but in 20 years it’ll mean something to you and it will help.” Charles Doucette

Governance

Risk management—Nujo’tme’k Samqwan/Wolankeyutomune Samaqan

There is no legislation establishing standards of care for drinking water in First Nations, and only minimal standards addressing wastewater effluent requirements. The AFNWA exists in a largely unregulated and unenforced environment, despite decades of effort to improve drinking water for First Nations (

Canada 2006), including past (Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act, 2013; repealed) and current (

First Nations Clean Water Act, Bill C-61 2023) attempts at developing federal legislation. During the March 2017 Elders engagement session, the following thoughts were shared by Elders and have been incorporated into the AFNWA governance model (

APC 2017):

“Water must be looked at in a wholistic way – it is connected to the ecosystem of the forest, air, and soil, as well as people and communities”

“Nature has rights and humans have responsibilities. Stewarding the health of Mother Nature is a responsibility”

“We need enhanced wastewater monitoring”

To ensure the AFNWA’s internal standard of care addressed these key values, the AFNWA turned to the EAL to guide the development a risk management approach for water, from source to tap and back again that connected First Nations values and natural laws to drinking water and wastewater treatment standards. Central to First Nations culture is the understanding of their obligations to protect

Msit No'kmaq (all my relations) through the Mi'kmaq concept of

Netukulimk. Netukulimk is a collection of Mi'kmaq sovereign laws, collective beliefs, and behaviours that inform how humans should protect, utilize, and preserve Earth and all features of the land to honour sustainability for present and future generations (

Prosper et al. 2011; and stories shared by the members of the EAL). Because of the Mi'kmaq and Wolastoqiyik peoples’ fundamental understanding of life as cycles of interconnected pieces of a whole, the AFNWA considers drinking and wastewater management practices as one cycle, to ensure a balanced and holistic accountability to the protection of safe and clean

samqwan (water). To honour and implement Two-Eyed Seeing and the interconnectedness of all water in the care of humans the Elders, in collaboration with CWRS, developed Nujo’tme’k Samqwan (we take care of the water). This process is a cyclical continuous improvement cycle built on the WHO’s Water Safety Plan approach to reducing the risk of unsafe drinking water and unclean wastewater.

Dispute resolution

An important and culturally distinct element of the AFNWA management is (what western organizations term) dispute resolution. From a First Nations perspective, when disagreements or tensions arise, the goal of reconciliation is to reestablish balance and harmony. The EAL developed a dispute resolution process of talking circles to be conducted with a guiding set of Wabanaki principles, gepmiteetmg (confidentiality), nestaweltetasimg (consensus), tetpoltimg (equality), apisitatimg (forgiveness and healing), and wetapegsoltimg, an acknowledgement that we may be unaware of the life experiences of those who enter the circle. The traditional way of addressing disputes involves four stages: oplamatimg, ptagmatimg, eilamatimg, and apisitatimg. These translate to sharing feelings and identifying issues, finding calm and de-escalating, talking to find a shared understanding, and forgiving each other and finding consensus. The AFNWA is in the process of developing its approach to maintaining balance and harmony through on-going discussions with the EAL.

“As Indigenous people, when we agree to something, we put all of our heart into it because we know we’re going to live up to it. We don’t have to sign a bunch of agreements and articles. With that said, there is the need for some sort of formal recognition that needs to be done. I’ve always really liked the idea of the reintroduction of the Wampum Belts as a sign of goodwill and peace among the group. Maybe one of the ideas is introducing Wampum belts about getting back to balance again.” Ken Francis

The AFNWA is owned and operated by the First Nations who have signed on to the organization and it provides a collective approach to water services. As First Nations return to self-governed ways of working together, they will develop governance frameworks and mechanisms grounded in their culture and values. These examples of Indigenous approaches to risk management and dispute resolution are just two frameworks guided by Two-Eyed Seeing that include elements of First Nations and western knowledge to produce the best solutions possible.

The next steps in the journey

As a new organization, the AFNWA’s success will be determined by its ability to blaze a new trail away from First Nations’ painful history of failed federal water and wastewater provision toward a service model guided by Two-Eyed Seeing. Safe and sustainable water systems are possible in First Nations when built on the foundation of respecting traditional knowledge and culture while investing in leading-edge treatment processes, proactive risk mitigation, and pragmatic asset management. AFNWA has taken a positive step in this regard by embedding itself in the First Nations that own it and working to restore and honour the traditional relationship with water that has been dormant under the federal system. This Two-Eyed Seeing commitment to culture and engagement coupled with the expertise and resources to operate, maintain, and repair First Nations infrastructure will build long-term credibility and trust for the utility. There is much work to be done as the AFNWA begins significant operational development and capital investments and upgrades outlined in its 10-year business plan. As the AFNWA advances its mission, it will continue to tell the story of how the utility came to be and the importance of Two-Eyed Seeing to ensure the best of Indigenous and western knowledge is brought together to serve First Nations.

Continued capacity building for Two-Eyed Seeing

An important part of this new path forward will be advancing knowledge sharing and collaboration between First Nations and non-Indigenous service providers, including engineers and consultants. The AFNWA provides a model of how Indigenous technical organizations can serve as ambassadors of Indigenous values and culture for non-Indigenous people working in the water and wastewater sector. One of the authors’ objectives in writing this paper is to provide context and examples of Two-Eyed Seeing to non-Indigenous practitioners who may have limited awareness of the principle, but who want to learn more about “Etuaptmumk 101”. Together, Indigenous and non-Indigenous water stewards can work together to ensure safe drinking water and clean wastewater for First Nations now and for future generations.

Progress through storytelling

At the centre of the AFNWA mission and purpose is a dedication to self-determination. Through decades of persistence and leadership, First Nations have changed the landscape for water and wastewater provision in a variety of crucial ways. The 2021 First Nations Drinking Water class action $8 Billion settlement decision requires Canada to engage in prospective relief, so “the future will never again resemble the past” (Manitoba Court of Queen’s Bench 2021). The EAL share their voices and ideas through this article because telling and listening to stories is how we all learn. The authors hope that by sharing the story of how Two-Eyed Seeing guides the AFNWA, it will provide an example of how to ensure the future will never again resemble the past. First Nations-led solutions, like the formation of an Indigenous water utility, grounded in Indigenous knowledge, values, and culture, are the manifestation of self-determination and Indigenous water management. Indigenous scholar, Robin Wall Kimmerer, wrote in her book Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, stories are not instructions, but rather compasses, to provide orientation (Kimmerer, 2013). Through telling this story, we hope to provide an orientation to what Two-Eyed Seeing looks like in practice, so others can reflect on how these examples may be translated into action in their collaborations with First Nations and First Nations organizations. There is significant work to be done to address the longstanding inequities in First Nations drinking and wastewater services, and this work must be done through both eyes, to ensure safe water for future generations.