Introduction

The global Covid-19 pandemic, armed conflict, political disruptions, and numerous climate change-driven phenomena have, unfortunately, given us multiple opportunities to test the resilience of the global food system in recent years (

FAO et al. 2022;

United Nations Environment Programme 2022). We have seen both stronger points and points of collapse. For example, even when pandemic restrictions upended market chains, farmers with highly biodiverse production in Colombia, Nepal, Ecuador, Costa Rica, and Guatemala demonstrated their resilience by consuming their own foods as well as sharing them with others in their communities and networks (

Gómez Serna and Bernal Rivas 2020;

Adhikari et al. 2021;

Lyall et al. 2021;

Little and Sylvester 2022;

Rice et al. 2023). In some locations where unprecedented heavy rains coincided with pandemic disruptions, biodiverse production also buttressed farmers against the effects of crop losses and impassable roads (

Túquerrez 2022). Such stories of resilience stand in stark contrast to situations elsewhere. Perhaps nowhere has the interaction of globalized environmental, economic, geopolitical and public health disruptions been as evident as in Somalia. Russia's invasion of Ukraine meant that Somalia lost 90% of its wheat supply just as the country grappled with its worst drought in decades, ongoing armed conflict, remaining fallout from the pandemic, and rising global food prices. The confluence of these factors sent Somalia into a famine that saw an estimated 43 000 people die in 2022 alone, half of them children (

Wise 2022;

WHO and UNICEF 2023). While Somalia's circumstances are exceptional, they may be a harbinger of what is to come, particularly in a scenario where resources are increasingly depleted, nutrition and health disparities are broadening, and climate change brings new curveballs that affect the food system (

Shukla et al. 2019;

Willett et al. 2019).

Just as the disruptions of recent years have thrust the consequences of inequitable, fragile food systems into the global spotlight, they also present an opportunity to critically revisit and transform the structure of food systems. This interest propelled the development of the international collaboration network

Food Systems Innovation to Nurture Equity and Resilience Globally (Food SINERGY). The network was formally launched in March 2023 with a 3-day forum in Mont Orford, Québec, two pre-forum online workshops, and multiple small-group meetings. These inaugural activities united food system experts from 13 universities and research institutes as well as from 21 food policy advocacy groups, Indigenous networks, farmers’ associations, consumer organizations, social enterprises, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Participating individuals were located in 14 countries (Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Ecuador, France, Guatemala, India, Italy, Lebanon, Mexico, Moldova, Romania, Ukraine, and the United States), and the geographical scope of their collective expertise extended to many more locations.

Box 1 provides further information on Food SINERGY and the activity-based discussion methods used for generating knowledge outputs.

This article summarizes the knowledge generated by Food SINERGY discussions to date, with a focus on critical junctures for advancing equitable, resilient food systems. We situate the discussion points in the existing literature to reflect that the Food SINERGY network's expertise emerges from, and is embedded in, an extensive and evolving body of knowledge.

We begin by contextualizing the need for transforming food systems, then we move into a discussion on what constitutes food system resilience and how a food sovereignty focus can better support equity. Next, we present three avenues that Food SINERGY identified as key to creating equitable, resilient food systems. The first of these avenues, transformation across scales, discusses how resilience can be built across the local-to-global spectrum by simultaneously supporting food sovereignty and equitable international trade, as well as through seeking consonance across scales. The second, learning from stories of resilience, discusses how a diversity of innovations are challenging the conventional political and economic discourse around food systems, and highlights agroecology as a promising integrated innovation. The third, knowledge for transformation, presents the need for critical thinking around how we produce, mobilize, and ultimately use knowledge in order for it to better serve equitable, resilient food systems. We conclude by summarizing key learnings.

Why do we need to transform global food systems?

Multiple geopolitical, economic, environmental, and public health stressors have made access to nutritious foods less equitable both between and within countries. For example, as food prices soared to record highs in 2022, the world's poorest countries saw their food import bills increase by nearly $5 billion (

IPES-Food 2023). Ultimately, many of these countries were unable to produce or import enough food to feed their populations, contributing to record levels of acute food insecurity affecting 258 million people in 58 countries (

FSIN and Global Network Against Food Crises 2023). Wealthy countries were not spared from the pandemic's effects; in Canada, household food insecurity reached an all-time high, as did food bank visits (

Li et al. 2023).

Such stressors also affect within-country equitable access to nutritious food. In numerous countries, the domestic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic varied according to gender, age, socio-economic status, and employment conditions (

Picchioni et al. 2022). In particular, women-headed households, informal workers, and young adults who relied on daily wages were most likely to face severe food insecurity (

Picchioni et al. 2022). Moreover, populations who were already at higher risk for nutritional deficits not only consumed smaller quantities of food due to the pandemic's economic effects, but also shifted toward less healthy diets, with more people eating ultra-processed foods, rather than fruits, vegetables, and fresh foods (

González-Monroy et al. 2021;

Naughton et al. 2021). In 2021, a staggering 42% of the global population was unable to afford a healthy diet (

FAO et al. 2023).

The connections between the food system and environmental change are especially concerning. The food sector is currently responsible for about a third of the total greenhouse gas emissions that drive climate change (

Shukla et al. 2019;

Crippa et al. 2021), and is also the largest cause of biodiversity loss, deforestation (

Díaz et al. 2019), freshwater overconsumption, and waterway pollution from nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers (

Rockström and Karlberg 2010). Without systemic changes, emissions from the global food sector alone could make it impossible to limit warming to 1.5 °C and difficult to realise even the 2 °C target (

Clark et al. 2020). Therefore, rethinking our global food system will be necessary to meet climate targets set out by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Climate Agreement (

Willett et al. 2019;

Rockström et al. 2020). At the same time, it is also essential to rethink food systems to adapt to and mitigate the effects of specific pressures such as heat stress, droughts, flooding, salinization, desertification, ocean acidification, pests, and infectious disease, all of which are projected to increase in the future as a result of climate change (

Shukla et al. 2019). This is all the more pressing given the links between climate change, resource pressures, and geopolitical conflict, including armed violence (

Hsiang et al. 2011).

Two connected and deeply entrenched barriers to systemic transformation are the asymmetric, highly concentrated power dynamics in global markets (

Clapp 2006;

Swinburn et al. 2011) and the pervasive momentum toward agricultural intensification (

IPES-Food 2016,

2017). Crop intensification based on mechanization and heavy use of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers was the predominant strategy for feeding the growing global population over the past century. While this came at the expense of habitats, soils, agrobiodiversity, and farmer health (

Sherwood 2009:

Holt-Giménez et al. 2021), in 2009, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimated that the world already produced more than 1½ times enough calories to feed everyone (

Holt-Giménez et al. 2012). Despite such caloric bounty, close to a third of the world's population (29.6%) faces moderate to severe food insecurity, with nearly one in 10 individuals (9.2%) experiencing hunger. These figures highlight a backward slide in the global goals to end hunger (

FAO et al. 2023).

Meanwhile, the global burden of hidden hunger, referring to micronutrient deficiencies, is estimated to be even worse than that of chronic hunger (

Gödecke et al. 2018). To understand this failure, it is helpful to examine the types of calories that are produced through agricultural intensification. Global markets have pushed a global dietary homogenization, wherein only three products (corn, wheat, and sugar) account for almost 50% of calorie consumption, while 10 products account for 80% (these are, in decreasing order of importance: corn, wheat, sugar, rice, soybean oil, beans, palm oil, cassava, beer, potatoes) (

Falconi et al. 2017). This homogenization comes at the expense of the variety of foods needed to sustain nutritious and culturally diverse diets, and the associated production patterns displace biodiversity in the agricultural ecosystem (

Herforth et al. 2019). While continued investment in these products will continue to increase caloric production, it will not resolve micronutrient deficiencies or inequitable food distribution and will more likely augment obesity and diet-related chronic diseases (

Herforth et al. 2019), adding to a growing double burden of under- and overnutrition (

Shrimpton and Rokx 2012).

Agricultural and dietary homogenization is largely the result of productivist global market dynamics that prioritize short-term profits and ignore externalities to human health, equity, or the environment (

Herforth et al. 2019;

Hendriks et al. 2023). Aiming to stay afloat in this globalized economic setting, many countries embark on a “race-to-the-bottom” in which they lower their export prices to compete with each other. As a result, regions that prioritize commodity exports over meeting domestic food demand, such as Latin America and the Caribbean, experience ever-worsening “caloric unequal exchange”, meaning that they have to export a much greater volume to import a monetarily equivalent amount (

Falconi et al. 2017). Doing so, these countries feed the world at the expense of their own population's food security and nutrition, their own natural resources, and their own ecological stability (

Falconi et al. 2017). It is tragic and ironic that, while an estimated 3.8 billion people around the world live in households that rely on agriculture, forestry, and fishing (

FAO 2023), these same people are collectively the most food insecure, malnourished population group on the planet (

Berdegué and Fuentealba 2011;

FAO et al. 2023). Hence, hunger and malnutrition prove to be problems of inequality and inequitable relationships in different food system components and across scales (

Holt-Giménez et al. 2012;

Falconi et al. 2017;

Herforth et al. 2019).

Looking ahead, it is certain the global food system will continue to face unpredictable disruptions from both short-term and long-term stressors (

Shukla et al. 2019). Long-term stressors such as climate change and biodiversity collapse are especially concerning because we have yet to see the full consequences of what has already been set in motion (

Wu et al. 2015;

Lafuite and Loreau 2017;

Ding et al. 2020). For example, climate change inertia means global mean surface temperature peaks 25–30 years after emissions are released, so in any emissions reduction scenario, there is a certain amount of warming that is inevitable in the coming decades (

Samset et al. 2020). This adds to the urgency of food systems transformation.

Food system resilience

Food systems represent socio-ecological systems that include biophysical and social elements that are interconnected through feedback mechanisms (

Tendall et al. 2015). They encompass, but are not limited to, the activities of producing, processing, packaging, distributing, retailing, and consuming food, as well as the related societal, economic, political, institutional, and environmental processes of these activities at different scales (

Ericksen 2008a,

2008b;

Tendall et al. 2015). Analyzing food systems often involves examining the determinants, or drivers, of how food system activities are performed, as well as their outcomes (

Tendall et al. 2015).

The concept of “systems resilience” originated in ecology theory with respect to a system's capacity to withstand or adapt to predictable and unpredictable disturbances over time to continue fulfilling its functions and provide favourable outcomes (

Hoddinott 2014;

Tendall et al. 2015). Tendall and colleagues draw on this history as well as on the concept of food security (discussed later in this article) to define

food system resilience as “the capacity over time of a food system and its units at multiple levels, to provide sufficient, appropriate and accessible food to all, in the face of various and even unforeseen disturbances” (

Tendall et al. 2015). They propose resilience as complementary to sustainability, clarifying that sustainability “has been broadly defined as the capacity to achieve today's goals without compromising the future capacity to achieve them”, whereas resilience incorporates “the dynamic capacity to continue to achieve goals despite disturbances and shocks”.

For the Food SINERGY network, the focus on resilience reflected the need to respond to increasingly perilous and frequent disturbances driven by climate change and resource depletion, including both their explicitly environmental manifestations (e.g., storms, droughts) as well as related social, economic, and political phenomena (e.g., climate refugees, conflicts over resources). Ecological theory around resilience emphasizes the importance of diversity (e.g., of species, of functional groups) for promoting productivity and stability (

Holt-Giménez et al. 2021). Similarly, to construct resilient food systems, diversified strategies must be implemented to build stable redundancies and stopgaps into the food system, such that if one strategy fails, others can quickly and effectively fill the gap before negative consequences occur to planetary and human health and well-being.

Equity through food sovereignty

The Food SINERGY network emphasized the importance of system

transformation, noting that sustainability should not “sustain”, and resilience should not “bounce back to”, an inequitable and underperforming food system. In that both resilience and sustainability are tied to outcome-driven goals, they theoretically preclude the possibility of enhancing systems with undesirable outcomes and are inherently transformative. Even so, there exists a danger that notions of resilience in food policy discourse can be co-opted to a reductive focus on productivity and economic growth, at the expense of equity. As Holt-Giménez and colleagues warn, “without attention to relations between small scale farmers, institutions, scientific practice, markets and state power, without addressing the broader context of sovereignty of land, resources and knowledge, resilience building will be ineffective at best” (

Holt-Giménez et al. 2021). For this reason, the application of diversity as a cornerstone of resilience must be applied as a cross-cutting element (

IPES-Food 2016), referring to, among others, diversified trade arrangements, diversified market supply, diversified production, as well as social, cultural, and ecological diversity. While diversification is important, it is not enough to secure equity on its own, as it does not rectify power imbalances (

Holt-Giménez et al. 2021). Therefore, Food SINERGY identified food sovereignty as an organizing and guiding concept to promote equity in food system resilience.

Food sovereignty is a concept popularized by Via Campesina, an international network of peasant farmers, Indigenous Peoples, landless workers, pastoralists, fisherfolk, and smallholder farmers. In 1996, Via Campesina defined food sovereignty as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems” (

Via Campesina 2007). This declaration further described specific applications of food sovereignty for rectifying imbalances around human rights, economic power, and resource use

1. Since Via Campesina articulated the concept, food sovereignty has become central to the political discourse of peasant associations, Indigenous Peoples, and numerous civil society organizations around the world (

Jarosz 2014). While the meanings of food security and food sovereignty are closely intertwined (see

Box 2 for an overview), some propose that food security is largely

descriptive, offering an end goal, whereas food sovereignty is largely

prescriptive, offering not only a definition, but also guidelines on how to get there (

Clapp 2014).

Although academic discussions on food system resilience and health equity have drawn more heavily from food security (

Tendall et al. 2015;

Weiler et al. 2015), Food SINERGY in fact found the integrated approach of food sovereignty to be more pragmatic for equity promotion. For example, food sovereignty asserts not only the right to sustainably produced food, but the rights to democratic management of productive resources (land, water, seeds) and to fair terms of trade. Doing so, the food sovereignty lens enables comprehensive responses to interlinked environmental and social equity issues in the food system (

Levkoe and Blay-Palmer 2018), such as by drawing attention to how concentration of corporate power has contributed to ecosystem mismanagement, hunger, diet-related chronic diseases, as well as occupational health crises (i.e., pesticide exposure) (

Weiler et al. 2015).

Moreover, it is critical to credit the leadership of peasant organizations and of Indigenous Peoples in defining and advancing food sovereignty (

Via Campesina 2007;

Morrison 2011). While Indigenous involvement in Via Campesina's initial conceptualization was largely limited to Latin America, Indigenous scholars in North America have since proposed “Indigenous food sovereignty”, which expands on the initial rights-based focus to also include a culturally embedded responsibility to care for food systems (

Morrison 2011) such that Indigenous Peoples could move “beyond surviving to thriving” (

Maudrie et al. 2023). In practice, food sovereignty and Indigenous food sovereignty have both proven instrumental for mobilizing tangible food system changes (

Levkoe and Blay-Palmer 2018;

Delormier and Marquis 2019;

Blanchet et al. 2021). Hence, Food SINERGY found that centering food sovereignty is also a means of respecting the perspectives of the groups whose present circumstances and historic trajectories have made them the most intimately knowledgeable of the food system changes that are needed.

Takeaway messages from the food SINERGY forum

Food SINERGY was convened out of a shared concern over the food system's staggering culpability in climate and environmental change, and its implication in a multitude of social, economic, geopolitical, and public health quandaries. By the same token, transforming food systems has monumental potential to improve the environment, provide just livelihoods, address malnutrition, and reduce the frequency and severity of armed conflict and infectious disease (

Willett et al. 2019;

Clark et al. 2020;

United Nations Environment Programme 2022;

IPES-Food 2023;

United Nations 2023). In terms of climate change alone, transforming the global food system can significantly mitigate future climate change while also making the system more resilient to the consequences of it (

Shukla et al. 2019;

Willett et al. 2019;

FAO et al. 2022). Hence, it is a strategic entry point to pursue integrated solutions for complex, globally shared problems.

Synergy is achieved when an interaction or cooperation between multiple groups, actors, or agents produces a combined effect that is greater than the sum of each of their separate effects. This term speaks to the objectives of Food SINERGY to create transdisciplinary collaborations for food system transformation in favour of interacting and mutually reinforcing, positive societal impacts. We root these objectives in the cautious optimism expressed by diverse food system leaders who sustain that, in the light of uncertainty, new possibilities and pathways are opened (

Blay-Palmer et al. 2020) and that we need to challenge the narrative that there is no alternative (

Lappé 2023). Food SINERGY thus advances the below key points, intended to guide synergies, identify opportunities, and challenge narratives to transform food systems toward equity and resilience. These points are also summarized in

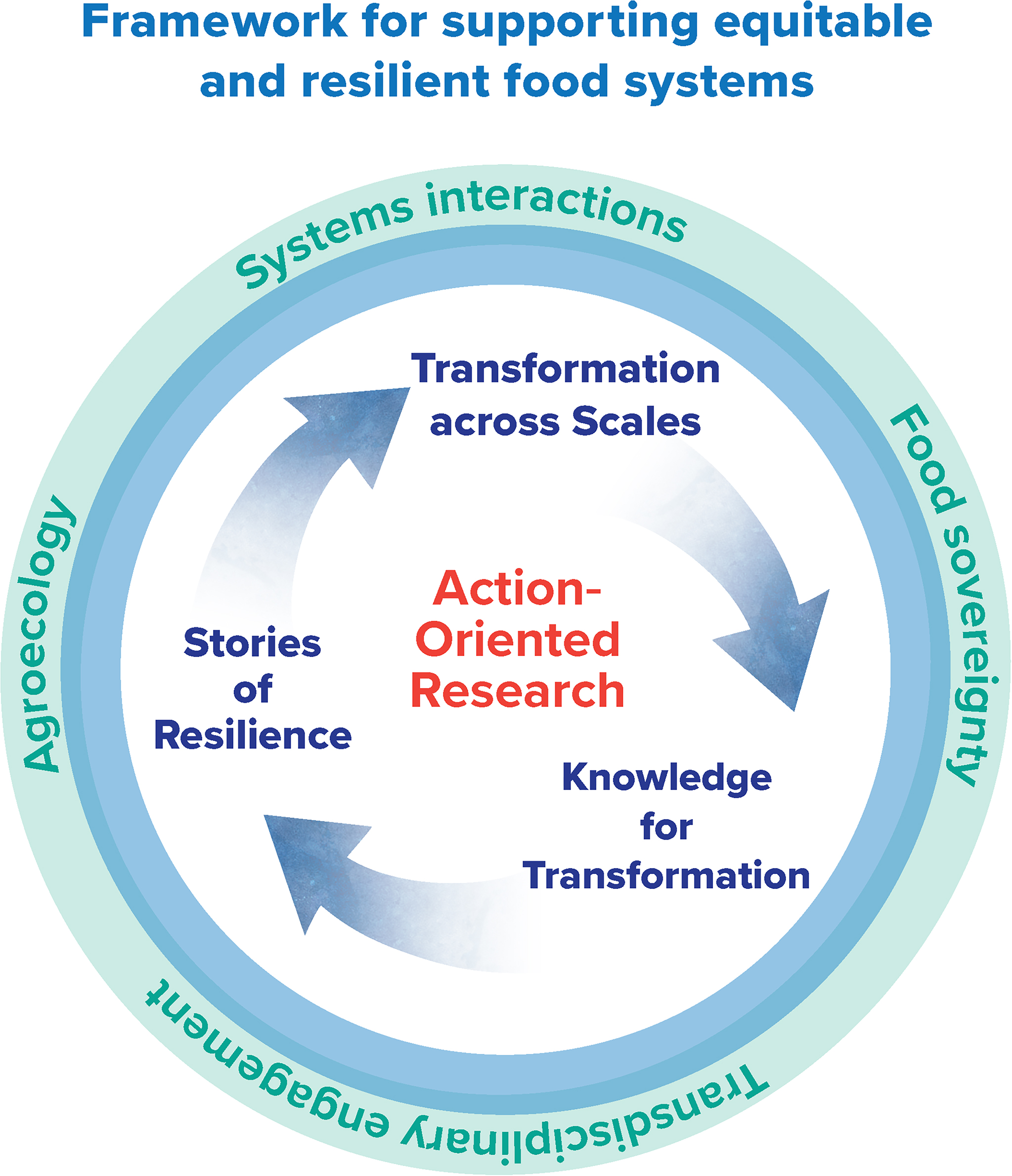

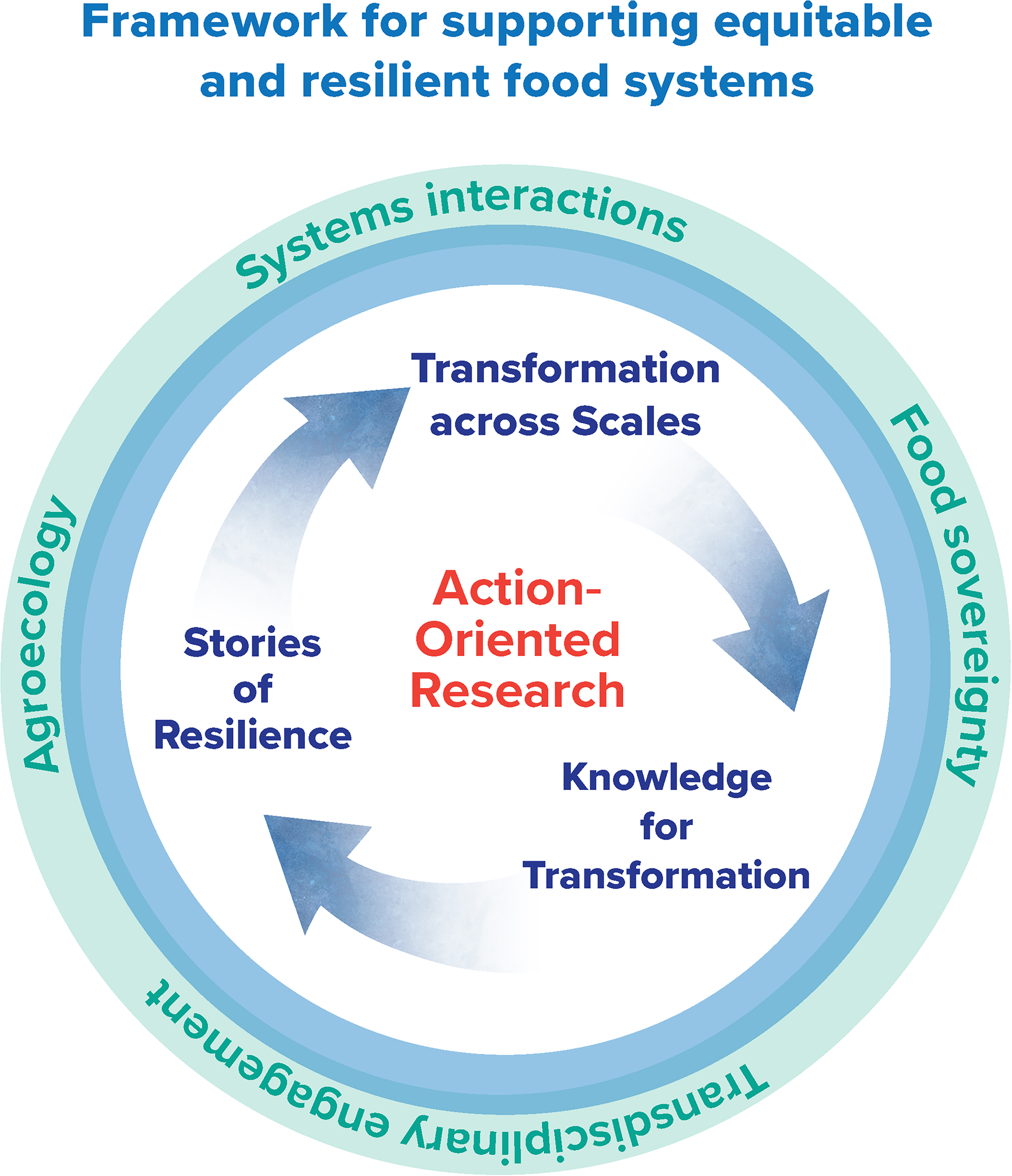

Fig. 2.

Food system resilience: Diversified strategies must be implemented to build stable redundancies and stopgaps into the food system, such that if one strategy fails, others can quickly and effectively fill the gap. As a cornerstone of resilience, diversity refers not only to diversified economic and production arrangements, but also social, cultural, and ecological diversity.

Equity through food sovereignty: Development of resilience must be transformative, such that it does not reinforce an inequitable food system. Key to this transformation is food sovereignty, an organizing concept that takes its lead from under-represented voices to provide guidance for addressing interlinked environmental and social equity concerns in the food system.

Transformation across scales: Local food systems and international trade must be reconciled to leverage complementarities between them. Food sovereignty must be supported not just locally, but at all geopolitical scales, and equitable trade agreements must be designed to protect food sovereignty around the world. To do so, it is necessary to seek consonance in policies across different scales.

Learning from stories of resilience: Existing innovations challenge predominant economic tenets and provide viable examples of how to support more equitable exchanges, more responsible resource management, and more favourable outcomes to human and environmental health and well-being. Agroecology stands out as an integrated approach that a diversity of actors, from peasant farmers to international agencies, have identified as key for equity and resilience.

Knowledge for transformation: It is necessary to build equitable and inclusive relationships between diverse types of knowledge, as well as move beyond knowledge production toward knowledge use. Participatory, transdisciplinary approaches provide tangible means for research programs to advance toward these objectives. In learning settings, a greater diversity of food system actors is key. Ultimately, research and education must not only seek to understand how food system transformation can occur, but actively contribute to shifting the food system narratives that guide decisions at all scales.