Methods

Rationale for case study

Within community-centric research specifically, a case study methodology provided the opportunity to focus time and energy on a single community or “case”, which allowed for meaningful discussions, relationship building, and reflections specific to the context of MFN (

Yin 2017;

Sadowsky 2019). Through this case study we applied a mixed-methods approach (

Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007) to investigate the “

how” and “

why” (

Yin 2017) when it comes to conducting wildlife monitoring and research “

in a good way”. However, as a single case study, this work is specific to the social, cultural, and geographic context of Magnetawan First Nation. Therefore, it is important to recognize that there are limitations to applying emergent themes or ideas within other contexts. Future case studies following a similar approach may be useful as replicates—allowing for commonalties amongst cases to emerge (

Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007).

Context

Efforts described throughout this paper were components of two MSc degrees, led by two graduate students (CK and KY), who frequently visited Magnetawan First Nation and worked closely with the MFN Lands Department on expanding terrestrial wildlife monitoring in MFN territory. However, this research is built upon pre-existing, long-term relationships between the research team (namely, JP) and the MFN Lands Department, allowing for collaboration founded in mutual respect and trust. The objectives of this paper were driven by the MFN Lands Department and their interest in expanding their wildlife monitoring program, which previously focused on reptilian species at risk, to include broader biodiversity monitoring. Conversations from the work of

Menzies et al. (2022) indicated a need to speak directly to community members about how to approach wildlife monitoring and research within MFN’s territory to inform not only the work of external researchers but also the goals and priorities of the Lands Department moving forward. These conversations were rooted in the need for change, recognizing that to create a better future for the next generations we need to come together to find new, creative approaches to conservation that place values and relationships at the forefront, as described by Richard Noganosh, an Elder from MFN:

“You're not going to do what things your father or your grandfather did for 100 years. When it comes to you, if you want the change, you know what's going on, you see what's going on. So, it's you that's got to change too so you can fix this, what your forefathers done. …Because you can't keep on doing the same things and hope everything's going to heal.” – Richard Noganosh

It is important to note that this work started in 2021, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. As such, the only way we were able to move forward with this work was by taking the lead from the MFN Lands Department and allowing them to determine COVID safety protocols for any researchers entering the community. Initially, community interviews and engagement activities were delayed until it was deemed safer, and we were, ultimately, invited to conduct research under community-led COVID protocols. In following these protocols, and through collaborative decision-making across the research team, some activities were adjusted or rescheduled as needed to best suit the health, safety, and comfortability for community members and all involved.

Interview procedures

Institutional ethics permissions were obtained, as required for research involving people (University of Guelph, REB #20-10-014). In addition, as per the principles of Ownership, Control, Access, & Possession (OCAP; First Nations Information Governance Centre (

FNIGC) 2023) and in recognition of the importance of multi-level consent (

Brugge and Missaghian 2006;

Harding et al. 2012;

Kelley et al. 2013), it was important for us to receive approval not only from the MFN Lands Department, but also from individual community members and interview participants. Prior to all interviews, participants were given written consent forms and were able to give either written or oral consent. In addition, throughout the interviews, we reminded participants that interviews were completely voluntary, and that they could withdraw their consent at any time. In accordance with OCAP principles, the audio files and transcriptions of all interviews were given to MFN Lands Department (i.e., to be “owned” and “controlled” by participants and/or MFN), but we emphasized that it could be withdrawn at any time. As a final step toward ethical and respectful exchange of knowledge, we presented each participant with an offering of tobacco, as per Anishinaabe customs, and gifted an honorarium in appreciation for their time and the knowledge they contributed to the project. To select interview participants, we asked representatives from the MFN Lands Department to suggest youth (under 30 years of age) and Elders/Knowledge Holders from MFN who could provide the most relevant perspectives and expertise about community values and how they can be woven into the wildlife monitoring process. In total, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 17 people (youth > 18 years old and Elders/Knowledge Holders), and held a sharing circle with 8 youth under 18 years old to increase their comfort and participation. In total, this represented ∼25% of community residents (

n = 100).

All interviews took place in person in Magnetawan First Nation, either at the Lands Department office or participants’ homes, depending on the preference of each participant. Most interviews took place individually, though some participants preferred to do their interviews in pairs. We combined interviews with a pre-planned, multi-day community visit (i.e., “intentional visiting”;

Tuck et al. 2022), which gave us the flexibility to schedule interviews that worked with participants’ schedules and provided opportunities for opportunistic interviews and follow-up discussions. A Lands Department employee (NP) was available, but not necessarily present, for all interviews to provide a familiar face to participants who may have otherwise been uncomfortable meeting directly with an external researcher, especially in their homes. Interviews lasted between 0.5–2 h, depending on how much each participant shared.

In addition to semi-structured interviews, we held a youth sharing circle (

Kovach 2009) during a youth event hosted by the MFN Lands Department. The sharing circle occurred in two spaces: (1) gathered around a fire in a public outdoor space within the community, and (2) outside of the MFN Lands Department office where youth painted a mural representing biodiversity and their relationships to the Land. It was important to community members that we ask the youth the same questions as adult participants, as to not diminish or “patronize” the wisdom and experiences of the youth. In place of an honorarium youth participants were entered into a prize raffle and were provided with pizza and snacks.

Interview questions

To gain insight into the values and priorities that are important to MFN and find ways to practice them within environmental monitoring in the community, we asked the following questions, which were developed in partnership with the MFN Lands Department:

1.

What is your relationship to the Land?

2.

Do you get out on the Land as much as you would like to?

a.

Is there anything that would help you spend more time on the Land?

3.

Do you think there are opportunities for youth to spend time on the Land with Elders and knowledge holders?

a.

If there are opportunities, would you mind sharing what these look like?

b.

Is there anything else you would like to share about Elder-youth engagement on the Land?

4.

Are there specific values or ideas that you think are important to consider in environmental monitoring?

a.

Are there any specific ways you would like to see the community give back to the Land?

While these questions set the themes we discussed in our interviews, the semi-structured approach allowed participants to guide the direction of our discussions based on what they wanted to share (

Kovach 2009). Starting with broad questions about personal relationships to the Land and opportunities to be on the Land allowed us to ease into discussions in a more comfortable and natural way before asking more directly about research and monitoring. This also allowed us to better understand how participants related to different values—as these were evident in many of the stories participants shared throughout.

Coding

All interviews and sharing circles were audio recorded and later transcribed using Otter AI Pro (version 3.20.0;

https://otter.ai) and then manually reviewed by CK. Interview participants were anonymized unless they wanted their name (in English or Anishinaabemowin) associated with quotes they shared, whereas all sharing circle participants remained anonymous.

NVivo (release 1.7, QSR International) and Microsoft Excel were used to code interview transcripts (by CK) through deductive coding (using codes based on pre-determined themes stemming from interview questions;

Fereday and Muir-Cochrane 2006). However, the conversational nature of semi-structured interviews also required inductive coding (extracting new themes based on participant answers;

Boyatis 1998) to account for unplanned themes. To create a rich, single case study, representative quotes have been used to illustrate emergent themes and ideas (

Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007); some quotes have been edited for brevity and clarity though the intent and message were left intact. Here, our pre-determined themes were based upon previous research between the MFN Lands Department and some members of the research team (see

Menzies et al. 2022). Given that conversational interviews were directed by participant responses and therefore did not always follow a particular structure or order, each interview was coded in its entirety to detect emergent and pre-determined themes rather than coding for specific questions in isolation.

Results sharing with community

As suggested by the MFN Lands Department, prior to community-wide sharing participants were visited one-on-one to go over any direct quotes that were being used from their interview. This was also used as an opportunity to confirm how participants wanted their name to be presented (in either English, Anishinaabemowin, or as anonymous). While no participants opted to remove their name from their contributions at this time, several participants did choose to switch from being anonymous to having their name represented after being able to see their quotes and the context in which they were used.

To facilitate results sharing, we invited community members to join us for food, wildlife photo viewing, and a presentation on our research results at the MFN Community Hall. Invitations were sent out as flyers, through in-person visits and word-of-mouth, and on the social media accounts of the MFN Lands Department. Attendees were invited to share feedback throughout the presentation, be it something to change or a topic for discussion, as well as confirm if/how their knowledge and identity were shared. In addition, all attendees were provided with a feedback form to share their thoughts or commentary related to the results, as well as provide insights for future research directions. There was no explicit need for changes identified within our results; however, there was a lot of fruitful discussion about data interpretation and how it can be used by the community going forward. Following our results sharing event, a summary report was made for the MFN Lands Department including discussion from the event for them to have and disseminate as they wish.

Results

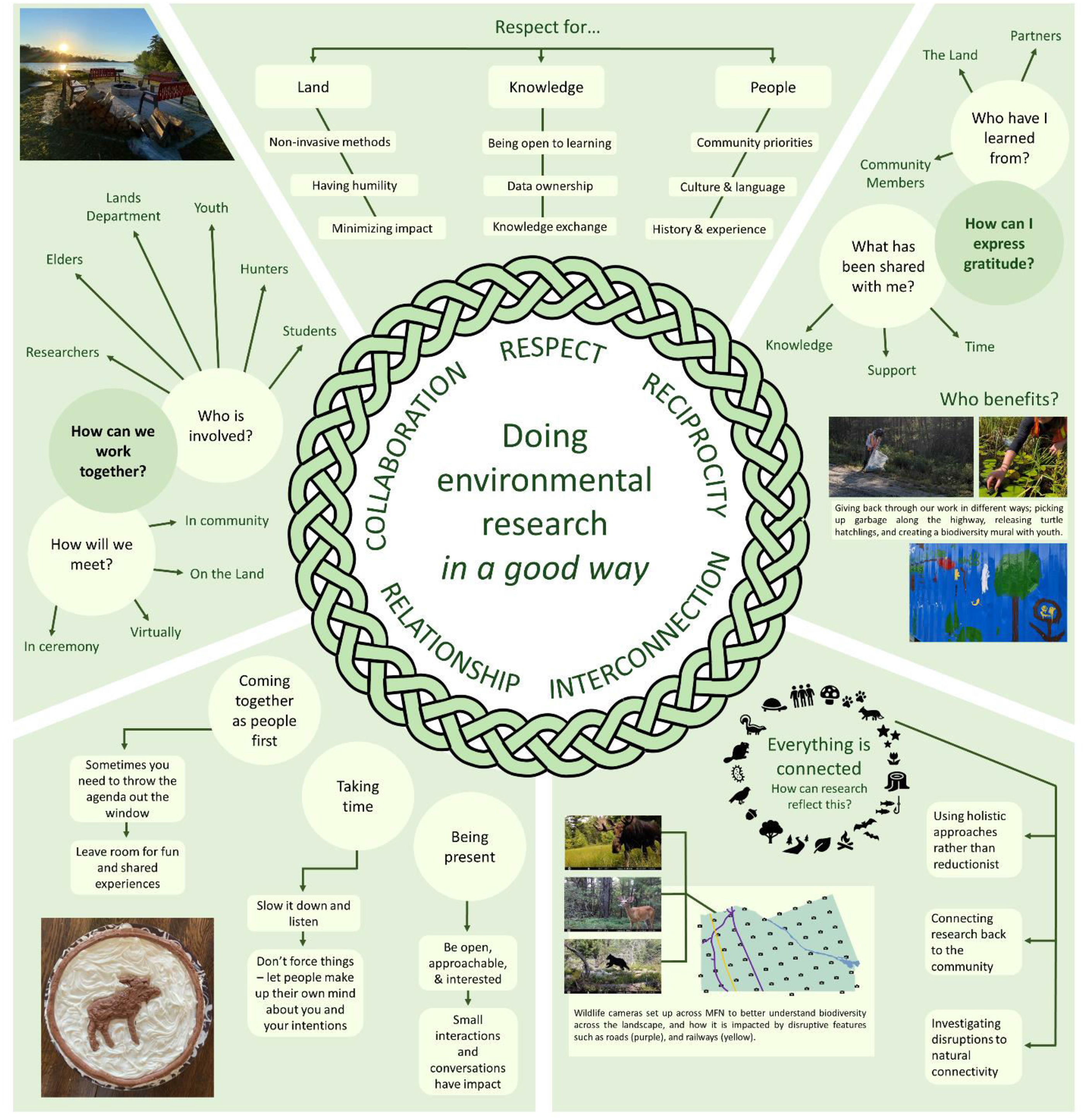

Exploring values to guide environmental monitoring

When we asked participants about the specific values that should and do guide environmental monitoring and stewardship, many were shared, including:

respect, interconnection, reciprocity, collaboration, knowledge transfer/communication, relationship, mindfulness, support, responsibility, spirituality, humility, understanding, adaptability, openness, trust, gratitude, and

transparency. Each of these values was identified in relation to caring for the Land by at least one person, either directly or indirectly, through a story, for example. Below, we highlight the five most frequent values,

respect,

interconnection,

reciprocity,

collaboration, and

relationship; share how they were defined by participants; and describe how participants would like to see them reflected in Lands-based work within MFN in the future (

Fig. 1). Note that although

knowledge transfer/communication was also one of the most common values, it is not included independently because it was often embedded within the other values and is, therefore, described within those.

Respect

Respect was the most commonly discussed value in relation to environmental monitoring, and it was expressed in a variety of ways. Primarily, participants spoke about the need to have respect for the Land, respect for people, and respect for knowledge. Several participants also mentioned the inherent value and spirit of animals, and the need for research methods that consider and respect them as such. For example:

“That's part of who we are as a people…I don't see them [wildlife] as turtles or chipmunks or birds. They're spirits. And, we're supposed to help those spirits. We're supposed to all get along. And, how do I know that spirit isn't the spirit of my son?… He's probably a chipmunk because he's fun… He was always funny. That's part of that – the values that I see coming out of the Lands Department – is that respect for all of these creatures. The respect for the Land.” – Anonymous

Having respect for knowledge—both in itself and in the way it is shared and received—was also brought up as an important consideration, especially because of the lack of respect given to Indigenous Knowledges, historically. In many ways, respecting people and knowledges go hand-in-hand, and is reflected in the interactions that take place within community, as described here:

“Having a respect of knowledge, having a respect of people, of time, of place, of tone.” – Samantha Noganosh

Knowing that those who are entering into the community have respect for both people and place, and that they will share what they learn with the community, was also very important to many participants.

“Let us know what you see out there. Especially people that come in there, you don't know who they are, or what they're looking for, and they kind of don't have respect for what we have. They want to destroy [the Land].” – Tina Pitawanakwat

While there are many different ways respect could be expressed in research, some of the main tangible examples were listening to community knowledge, following community research priorities and questions, opting for non-invasive monitoring methods, and sharing knowledge and data with community members.

Relationship

The importance of creating and maintaining meaningful relationships with both people and the Land was highlighted by many participants. When we asked participants about their own relationship with the Land, and how they show respect for it, there was a wide variety of responses, but one commonality was the element of care. Participants expressed a deep connection with the Land, and many highlighted the importance of those working on the Land in the community to share this element of care. It was also important to many participants that community members have opportunities to meet those who will be working on the Land in the community's territory—so that they can see the level of care for the Land, and for the community—themselves.

“You know, when [biologists] come in here, they become part of that community too. So I mean, you have to start talking to people and whatnot, try to get along. …I don't mind people coming here, as long as they're doing their business, what they're supposed to, and you don't damage the place. You know? I mean, this is the only Land we have as people - we certainly don't want to get rid of it in that way.” – Anonymous

Ultimately, participants expressed that relationships are an important part of working both on the Land and within community, and that time should be taken to build these relationships.

Reciprocity

The idea of giving back and expressing gratitude was described as an important part of being in relationship, both with people and with the Land. When asked about giving back to the Land, many participants spoke about cleaning up garbage and ensuring things are always left the same—or better—than they were found.

In terms of reciprocal relationships between people, simply listening and having respect for what people have to say was brought up by many participants. Approaching questions in a culturally appropriate way was also discussed by several people, referencing being offered tobacco and having an opportunity to decide if they want to, or should, engage in what they are being asked. For example, one participant said:

“You know, if somebody wants something, they have to come and ask me…They give you the tobacco and you give them the answer…And that's the other thing about it, is you have to know the person to say, well, is this person really, honestly, truly…do they really need this? You know, because you can't just give them something that they could use to harm somebody else, so you have to think about that, too.”- Anonymous

In terms of enacting reciprocity in the research process, participants suggested a number of things. Several people mentioned the value of simply sharing knowledge back to the community—making sure that results are communicated with community members, especially in a way that is accessible and can be used for community benefit. For example, one participant spoke about their excitement for having reports and compilations of community interviews and knowledge prepared as a research outcome:

“I know that there'll be such huge value in a collective stories. So, I really look forward to all this being put together. And for us to have…a collection of community knowledge, it will just be really cool to have.” – Samantha Noganosh

One of the main takeaways from our conversations was that the specific acts of giving back are less important than the intention and reflection behind them. The meaning lies in taking the time to understand who has contributed, who benefits, and working to express appropriate gratitude to those involved.

Collaboration

The importance of collaboration and working together was also highlighted, thinking about the difference between meaningful and performative examples. Some people referred to the value of bringing in subject experts to assist with specific challenges or questions identified by community, seeing opportunities for learning within the community as well as for those being invited in. However, participants also shared stories of experiences working with external parties—including government, researchers, and consultants—where a lack of understanding or shared values was a barrier to successful collaboration. For example, one participant spoke about being at a conference at which representatives from various Indigenous communities expressed a disconnect between how they want work to be done and how consultants were approaching them:

“So, at the end of the conference…one of the [consultants] got up…and he says, “We didn't know we were doing wrong. And now we know. So now when we write up a proposal or try to get a job someplace on the reserve…now we know what your values are. We didn't know that before because nobody told us.’" – Richard Noganosh

Moreover, participants described the need for everyone to play their part, working together for the collective good, and to ensure there is space for others to live up to their own responsibilities. One important aspect brought up by several participants was the need for collaborations to be built on transparency and knowledge sharing:

“Working together too, unity, working in conjunction with each other. Lands should let us in the office know what they're doing…that's the only way things are gonna work, is that we have that information at hand. I know it's a word that's been overused so much, transparency, but it's true. There's got to be real transparency…not just words.” – Lloyd Noganosh

When it comes to establishing meaningful collaboration, participants emphasized the need for being guided by a foundation of shared values from the start, and to ensure that everyone involved has the knowledge and ability to make their contribution.

Interconnection

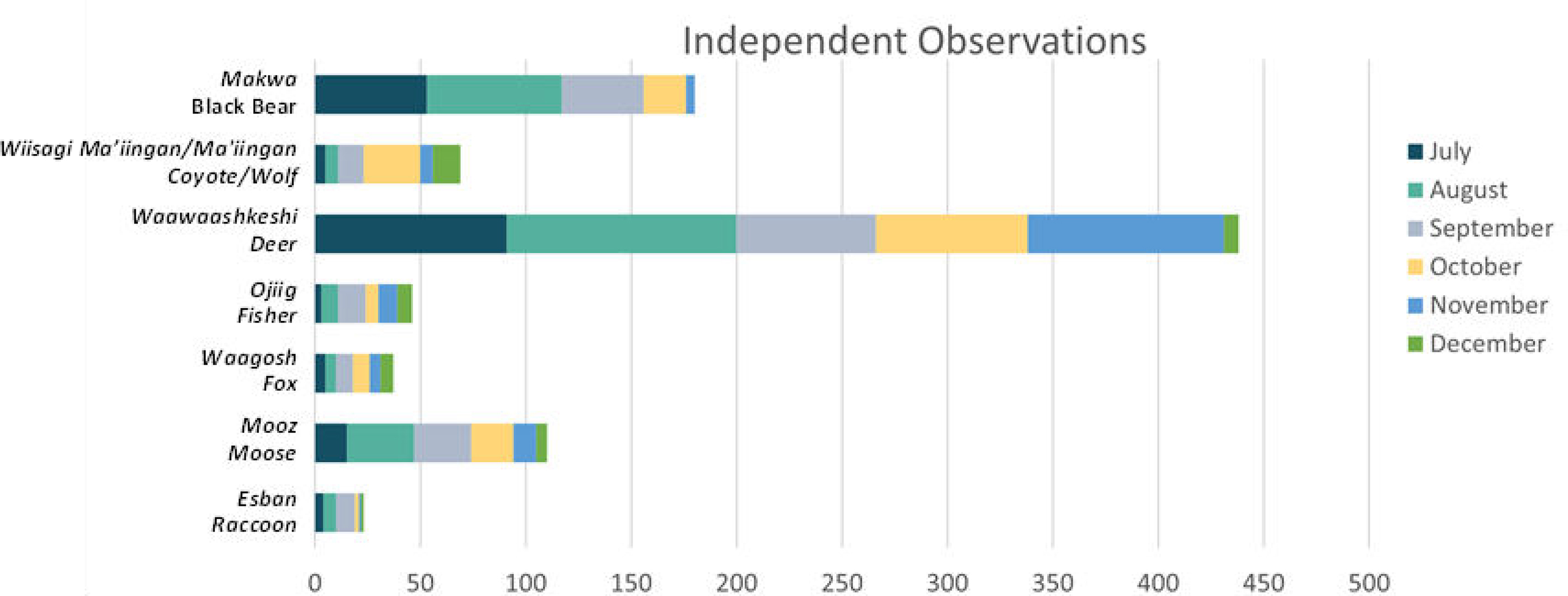

When talking about the Land, participants stressed how interconnected everything is. They emphasized the connection between current and future generations, and the need to make good decisions now to leave a healthy environment for those to come. This also led to discussion about the need for more holistic monitoring and research that asks questions not just about a single species or change on the Land, but looking more broadly to better understand and account for how species interact and coexist. For example:

“We're interconnected with everything. So, you take something away, it's going to impact. The moose need the beaver - they eat those roots in the swamp, that's medicine to them, that's their main diet. They're very connected. So, if the beaver's healthy, the moose are healthy. Look at the animals that are around and see how they're doing.” – Janis Smith

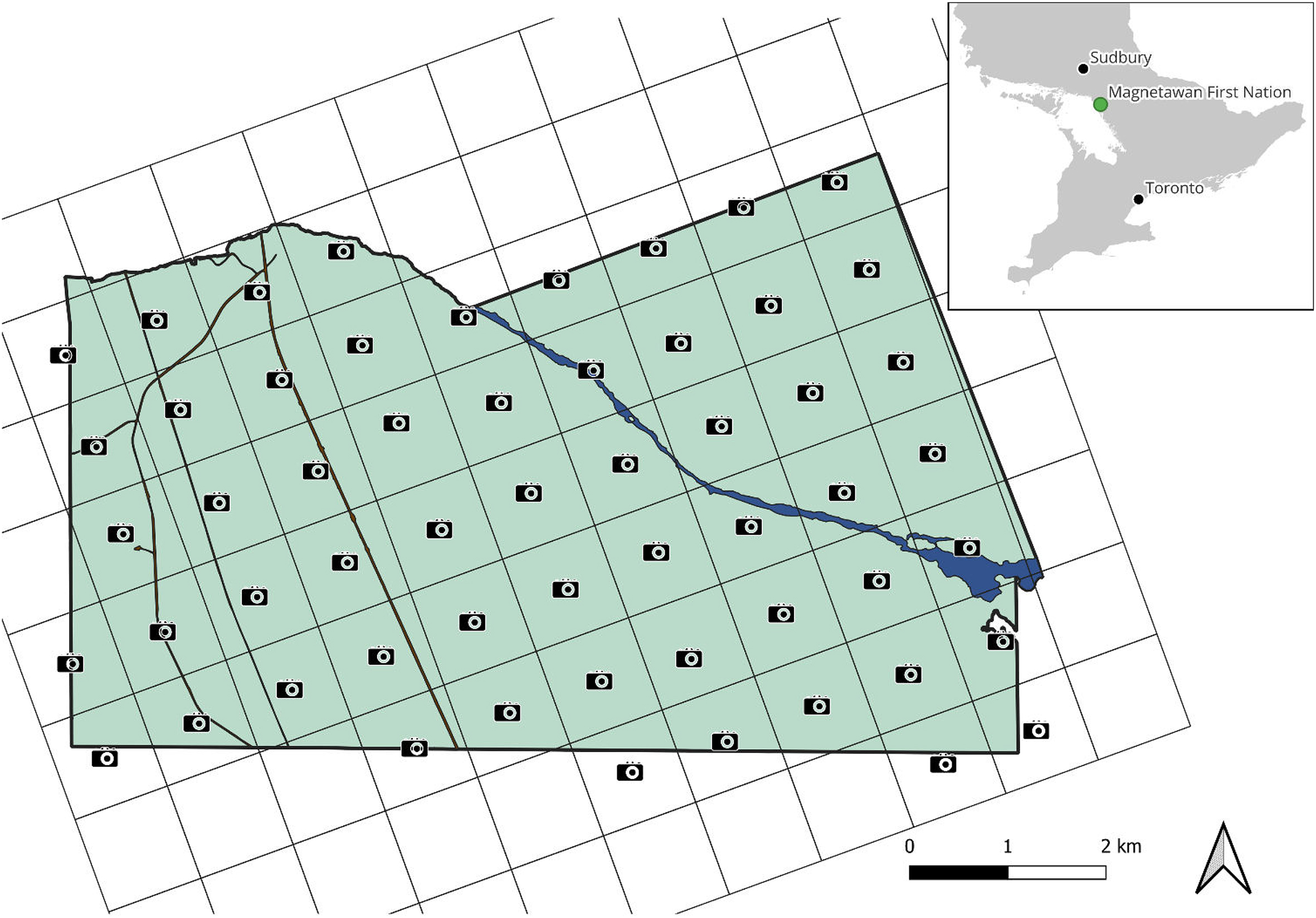

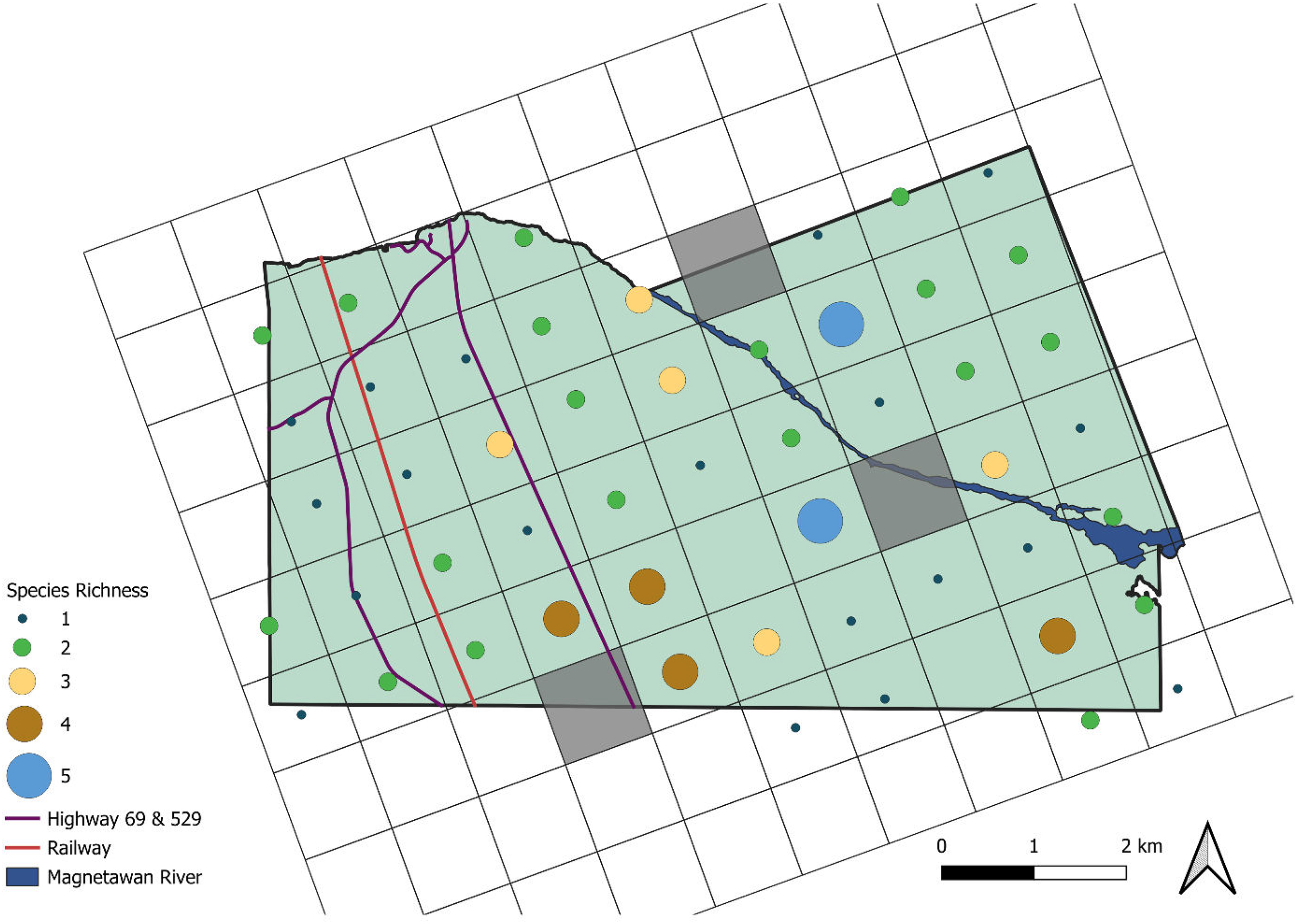

When thinking about how interconnected the Land is, participants also voiced concerns about things that cause disruption to this natural connectivity—specifically the railway and two main highways (highway 529 and highway 69, the latter of which is planned for a four-lane expansion) that cut directly through MFN Lands. For example:

“[An Elder] used to take me up on the trail there, up two-foot trail, and he used to say that they never used to go any more, any further than a mile to hunt. And once they put that highway there the animals disappeared. So, there must be a lot of things the highway does to animals. Maybe they're just…don't want to live in the area where there's, maybe noise, or whatever it may be. Or maybe they're getting run over more than anything." – Theodore Pitawanakwat

Accordingly, participants expressed that the community has a lot of questions about wildlife and how they are impacted by things that disrupt connectivity—like the highways and railway—and how to best mitigate the negative impacts.

Identifying community research priorities

In addition to thinking about values that are essential for guiding environmental monitoring, participants had a lot of ideas for future research priorities in the community. When it came to discussing wildlife monitoring and better understanding changes on the Land over time, the main considerations participants brought up were choosing research and monitoring methods that are non-invasive, creating a baseline of information about the presence and location of different species on the Land over time, finding opportunities for outreach and community engagement, and collecting data related to the highways and railway. These research priorities were shared by participants in the context of what they would like to see in current and future environmental partnerships, with emphasis on the impact for future generations.

Non-invasive methods

Participants expressed an interest in non-invasive research methods where possible, allowing for data collection that is respectful of the agency and spirit of the Land. For example:

“Progress affects everything…you need to have some, but you need to do it with less impact. And have that forethinking ahead, and think of…the next Seven Generations, all the children to come. Because we have to think about that, and people aren't.” – Janis Smith

Collecting reference information

Many participants spoke about the importance of understanding what is on the Land to inform future plans, ensuring things will be sustainable for future generations. This was discussed both in the context of gathering data now, as well as continuing to gather data over time.

“Now's the time, because in a five year feasibility study, you don't want to…figure out we should have done this five years ago because it takes five years. It's an absolute plan to come together and acknowledge what's happening in our environment.” – Anonymous

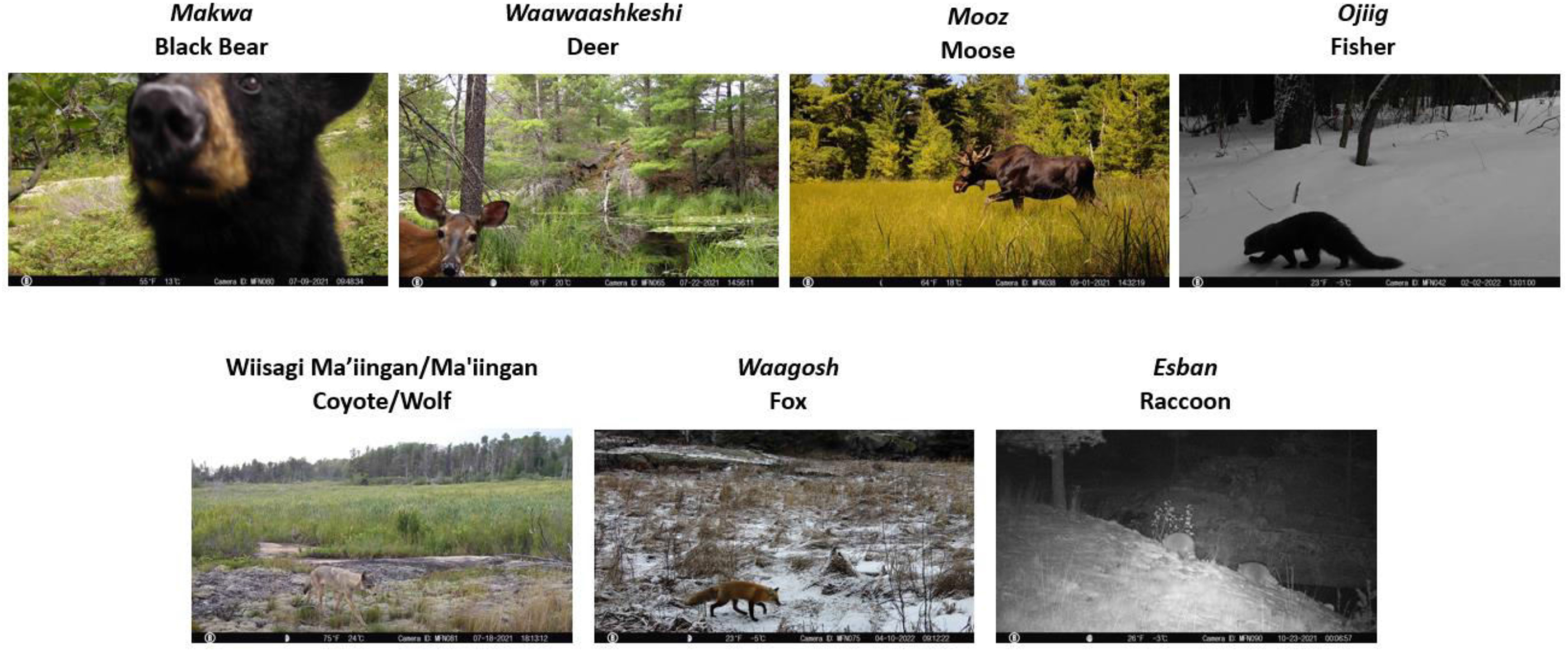

Multi-species approaches

In addition to thinking long-term, many participants spoke about the importance of looking at all species through more holistic approaches. There was interest in monitoring that would help inventory and produce documented records of wildlife within the community, to supplement the knowledge and oral histories that already exist within MFN.

“[We] have all kinds of interest…people in the community saying, “Well, what's really here?” There's a lot of things here that we still don't know that are here…there's other animals that are probably here.” – Jerry Smith

Outreach and engagement

Many participants expressed that while they love being out on the Land, many community members face challenges actually getting out because of accessibility or time constraints. Despite many people not getting out on the Land as much as they would like to, many participants expressed how much they love to see what is happening on the Land—big or small, such as:

“I think life is so important…even to watch what's on [the] Land, it's exciting to see. You see a rabbit running along and you kind of stop to watch it. Same with partridge, they sit up on the tree and they keep moving their head.” – Theodore Pitawanakwat

Some participants explicitly mentioned interest in wildlife cameras for outreach, saying:

“I think it'd be nice to have deer cameras. And then like, the random pictures that it takes just put up on a community page, or something.” – Neil Salt

Impacts of highways and railway

Better understanding how the highways and railways impact wildlife was specifically identified as a major priority for many participants. There was not only interest in a general baseline of quantitative data, but to compare wildlife data before and after the expansion of highway 69 to supplement the species at risk data that the MFN Lands Department has been collecting over the years:

“In the years to come, what's happened to the highway with the animals and that, once we put a four-lane highway through here, we need to keep an eye on it. That was one of the intentions of the original species at risk [program] was get some baseline information where we are on the highway here…Let's figure out how we're going to monitor this over the years of the highway.” – Jerry Smith

There is also a lot of community interest in new mitigation efforts along the highways that cut through MFN, such as wildlife overpasses, and participants expressed that they want to see monitoring that can support this advocacy:

“[Changing migration habits has] been my biggest concern about this new highway coming through…how to get them under or over the highway. So those are big things we're keeping in mind when we talk to [the Ministry of Transportation] in regards to that. And your work here is going to help with giving us support in that 100%.” – Angela Noganosh

It was important to hear directly from community to understand and identify research priorities that do not stem from an external research agenda. Knowing that participants want to see community-wide, multi-species monitoring that utilizes non-invasive approaches and prioritizes outreach and engagement was essential to developing a community-based monitoring program with MFN. Further, hearing that the community wants to know about impacts of the highway and railway, in addition to species inventories, was important in developing our corresponding research questions.