Introduction

Ending hunger and all forms of malnutrition and achieving food security by 2030 is the global wake-up call of the second Sustainable Development Goal (SGD-2) (

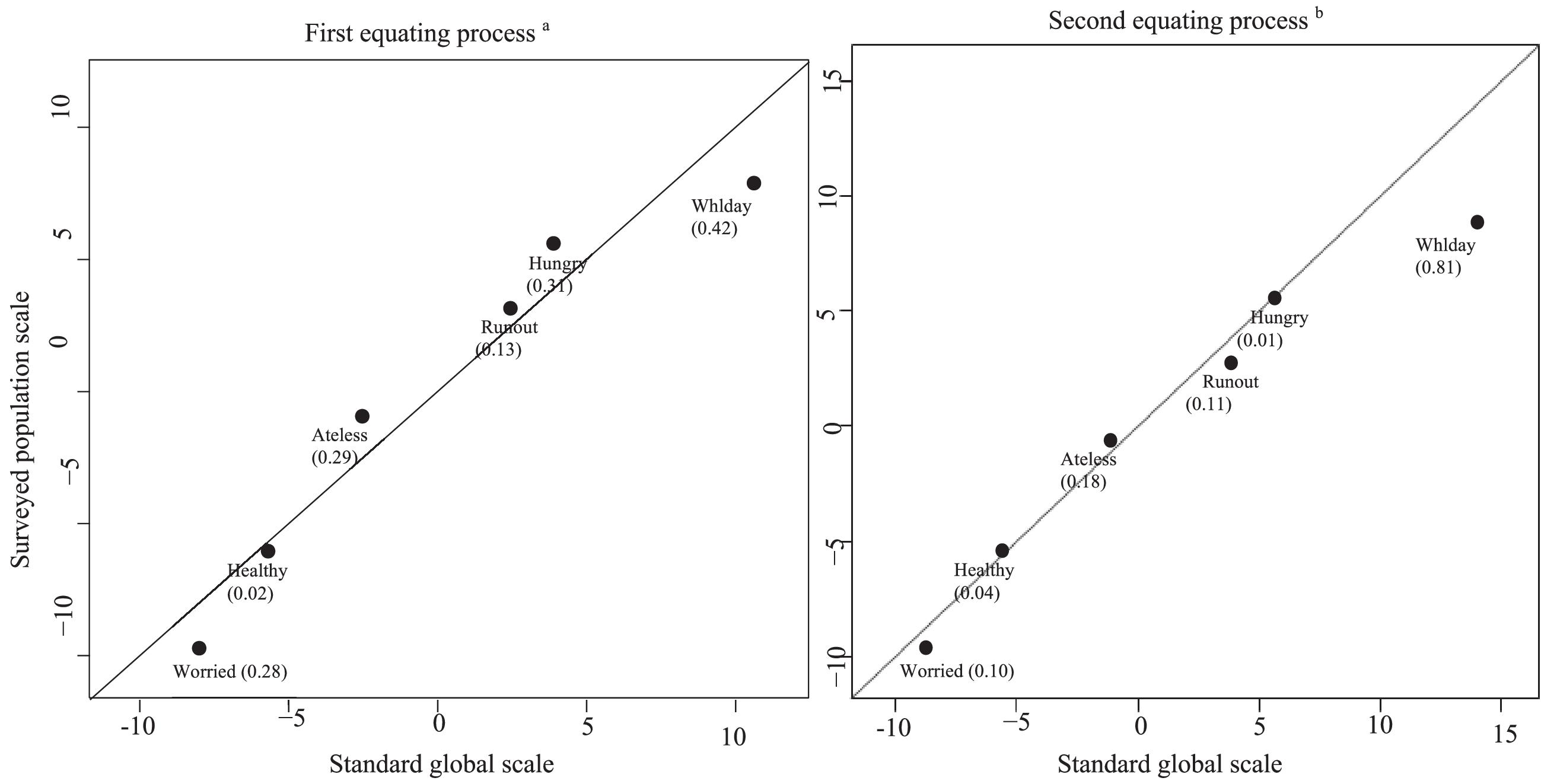

United Nations [UN] 2019;

Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO] 2022). However, in the 2021 report about the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World, several agencies of the UN system (FAO, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the United Nations Children's Fund, the World Food Programme, and the World Health Organization) reported that more than 2 million people in 2019 experienced moderate or severe forms of food insecurity (MSFI), thus declaring an unprecedented setback in meeting SGD-2 (

FAO et al. 2021a).

Like other unobservable or latent traits, food insecurity cannot be measured directly. However, it can be estimated (

FAO 2016a,

b). For this purpose, several food experience-based scales have been proposed (

Salvador Castell et al. 2015). Examples of these scales are the Latin American and Caribbean Food Security Scale (

FAO 2012) or the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (

Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project 2020), developed by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and its partners, including governmental and non-governmental organizations and academic institutions. However, the current recommendation focuses on using the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), considered the first MSFI measurement system based on experience with comparable results (

FAO et al. 2019). The “prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity of the population based on the FIES” is the indicator 2.1.2 of the SDG-2 (

FAO et al. 2019). Since 2019, FAO has reported its official MSFI statistics based on the FIES. The increase in MSFI in Latin America and the Caribbean was more pronounced than in other regions, reaching 41% in 2020 (

FAO et al. 2021b).

It has been noted that official data on this indicator may differ considerably depending on the institution or the year of reporting. In this way, in Ecuador, the FAO reported 32.7% of the MSFI in 2018–2020 (

FAO et al. 2021a), while the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses of Ecuador (INEC) estimated a range of values for the MSFI between 14.65% and 17.83% in 2017 (

Moreno et al. 2018). This MSFI range resulted from its estimation across various scenarios. Displaying results in diverse scenarios aims to assess the impact on prevalences by defining different groups of items, some of which were considered not comparable with the FAO's global FIES during the estimation process. This suggests a methodological dilemma concerning the use of this indicator, which may stem from various sources. Thus, variations among institutions obtaining the measurement could lead to different data collection methodologies or discrepancies in defining and measuring the indicator. In this sense, it has been suggested that the methodology for calculating MSFI prevalence according to international standards proposed by FAO may be somewhat arbitrary (

Moreno et al. 2018). Additionally, factors such as data quality, sample coverage, sampling methods, and reporting practices can influence the observed differences in the indicator across various reports and data sources. However, the MSFI estimate is just a methodological detail compared to achieving SGD-2, as COVID-19 and the measures implemented to contain it have substantially increased economic stress, unemployment, or the number of working hours, and also contributed to the decline in household income (

Erokhin and Gao 2020;

World Health Organization [WHO] 2022). All this may have had repercussions on the state of food security of the population (

Comunidad de Estados Latinoamericanos y Caribeños;

FAO et al. 2015;

FAO 2020).

In fact, global post-pandemic forecasts suggest that 265 million people worldwide will suffer from severe food insecurity, which is double the number compared to 2019 (

Famine Early Warning Systems Network [FEWS NET] 2020). In this regard, a study conducted in Chile compared the levels of food security prevalence before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, observing a significant increase in MSFI from 30% in 2017 to 49% in 2020 (

Giacoman et al. 2021). Similarly, a study conducted in Argentina in 2021 found a prevalence of MSFI of 47.29% (

Pantaleón et al. 2021); in this country, MSFI grew from 19.2% (2014–2016) to 35.8% (2017–2019) and severe food insecurity grew from 5.8% (2014–2019) to 12.9% (2017–2019), showing a progressive increase in this indicator in recent years (

FAO et al. 2020).

It has been estimated that, in 2020, women suffered 10% more from MSFI than men, compared to 6% in 2019 (

FAO et al. 2021b). The evidence shows that MSFI is a historical and structural problem present in women (

Jung et al. 2017), with an emphasis on female-headed households (

Negesse et al. 2020), black women, and women with less education (

Schall et al. 2022). It is known that women receive lower wages, have fewer savings possibilities, work in more insecure jobs, or live in poverty more often than men (

UN 2020;

Bapolisi et al. 2021). Hence, economic aspects and various social determinants, including gender, are related to MSFI (

Jung et al. 2017;

Negesse et al. 2020). Research conducted during the pandemic coincides with and reinforces the pattern of high prevalence of MSFI among women in countries like Brazil (

Schall et al. 2022) and the United States (

Belsey-Priebe et al. 2021). These studies highlight how women and households supported by females were the most affected by hunger and MSFI. Regarding Latin America, a study conducted in the early phases of COVID-19 found a high prevalence of MSFI in the region, as well as associations linking MSFI with female gender and residential area (

Benites-Zapata et al. 2021).

However, other characteristics should also be considered. For example, the analysis of the geographical areas where women reside has indicated a greater risk of MSFI in rural areas compared to urban areas, according to global statistics (

FAO et al. 2021a). Nonetheless, these findings might offer a generalized perspective and may not accurately depict the situation in each country. Thus, for instance, in 2021, a higher prevalence of MSFI was observed in urban areas compared to rural areas in Pakistan (

Ghulam et al. 2021).

The discouraging statistics showing the increase of MSFI in Latin America and Ecuador require permanent monitoring and the implementation of timely actions. It is worth noting that in the case of Ecuador, MSFI increased by 12 percentage points between the periods 2014–2016 and 2018–2020 (

FAO et al. 2021b). However, statistics often focus on the entire population, without distinguishing between men and women and rarely highlighting the specific needs of women or the persistent and disproportionate gender gap, which pushes them further into unemployment and poverty (

Diab-El-Harake et al. 2022).

There are harmful consequences for women's health associated with MSFI, such as increased anxiety and depression (

Trudell et al. 2021), overweight and obesity (

Hernández et al. 2017), and cardiovascular diseases (

Salinas-Roca et al. 2022). The problems of the high prevalence of MSFI in women also transcend the household, as they are associated with lower food variety and quality (

Larson et al. 2019), and have negative consequences for maternal, fetal, and child health (

Cunningham et al. 2015). Due to the elevated prevalence of MSFI in Ecuador, provisions for food sovereignty are explicitly outlined in several articles of its Constitution, namely 13, 15, 280, 281, and 413 (

National Assembly of the Republic of Ecuador 2008). In response, the Government of Ecuador enacted the

Organic Law of Food Sovereignty (2010), which mentions the State's responsibility to encourage the consumption of healthy and nutritious food in Article 3, and the

Organic Law of Rural Lands and Ancestral Territories (2018), aimed to address the needs of Ecuadorian Indigenous populations. Also, programs were developed to improve the nutritional situation of the population, including: the Integral Micronutrient Program focusing on pregnant women, infants, and children under 60 months (

Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador 2011); the National Agricultural Strategy for Rural Women (

Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock of Ecuador 2020), and the Intersectoral Food and Nutrition Plan-PIANE 2018–2025 (

Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador 2018). Additionally, in 2019, the

Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (2020) formulated a strategy to bolster food security in Ecuador. This initiative was implemented through the National Agricultural Strategy for Rural Women, engaging 1300 women in its formulation. The MSFI also influences Ecuador's social programs. Thus, during the period of data collection for this study (in the year 2020), the National Plan for Good Living 2017–2021 was in force. This Plan prioritized the development of productive and environmental capacities to attain food sovereignty and enhance rural living standards under Objective 6. The Plan also mentioned the imperative to narrow women's income gaps, eradicate all forms of violence, and promote women's empowerment (

National Secretariat of Planning and Development 2013).

Within the framework of SGD-2 monitoring, the objective of this pilot study is to analyze the differences in MSFI experienced by Ecuadorian women during the COVID-19 confinement, according to their sociodemographic and economic characteristics.

Results

In relation to sociodemographic and economic characteristics, the responses were collected from the surveyed population of 2058 women between 18 and 68 years, with an average age of 23 years. Among them, 61.0% of women indicated residence in the Andean highland region, and 75.6% reported living in an urban area. Additionally, 80.3% indicated working in the public or private sector, while nearly half (40.4%) disclosed having pursued university studies. Moreover, 70.7% stated being married or in consensual union, and 75.8% reported having one or two children. Finally, 73.5% indicated having economic resources for their expenses, while approximately half (50.6%) reported experiencing a reduction in income during the confinement period (

Table 3).

Regarding characteristics related to food insecurity, a notable proportion of surveyed women (41.2%) stated feeling concerned about having healthy food (Worried). Additionally, 25.9% expressed being unable to afford healthy and nutritious food due to a lack of resources (Healthy). Moreover, 16.1% indicated having consumed limited food varieties due to financial constraints (Fewfood), while 9.5% mentioned skipping one of their three daily meals due to inadequate resources to acquire food (Skipped). Responses below 5% were recorded for questions concerning eating less than what was deemed adequate (Ateless) and going without food due to financial constraints (Runout). Percentages were below 1% for the Hungry question—0.8% of women reported experiencing hunger due to not eating—and Whlday—0.1% of female respondents reported going an entire day without eating (

Table 4).

Significant differences were detected between the percentages of surveyed women who experienced MSFI according to whether they lived in the Amazon region (17.7%), the Ecuadorian Highlands (15.1%), or the Pacific Coast (10.4%) regions (

p < 0.01) (

Table 5). In this sense, the risk of experiencing MSFI is higher for women residing on the Pacific Coast compared to those in the Ecuadorian Highlands (OR = 0.65, 95% CI 0.48–0.90,

p = 0.01). The percentage of women who experienced MSFI was also significantly higher among women who were married or in consensual union (15.3%) than among those who were single, divorced or widowed (11.5%) (

p < 0.05). Accordingly, being single, divorced, or widowed serves as a protective factor against experiencing MSFI (OR = 0.72, 95% CI 0.54–0.95,

p = 0.02).

In relation to the economic characteristics of the sample, there were significant differences between the subpopulations of the two categories considered. Thus, the percentage of women who experienced MSFI was higher among women whose income dropped during confinement (16%) than among those whose income did not drop (12.4%) (p < 0.05). Also, the percentage of women who experienced MSFI among women who did not have money for personal expenses during confinement (32.4%) was higher than among those who reported having resources for personal expenses (7.6%) (p < 0.001). In line with previous findings, the risk of experiencing MSFI was higher among women who encountered a reduction in income during confinement (OR = 1.35, 95% CI 1.05–1.73, p = 0.02) and particularly for those with no income for personal expenses (OR = 5.83, 4.49–7.57,p < 0.001).

Prevalence rates of MSFI for the surveyed population and for the subpopulations according to sociodemographic and economic characteristics

The MSFI prevalence rate for the surveyed population was 16.99% (90% MoE = 2.59) (

Table 6).

The values of the MSFI prevalence rates for each subpopulation (

Table 6) were consistent with the percentages of respondents who experienced MSFI calculated from the raw scores (

Table 5): the higher the percentage of female respondents who experienced MSFI in a subpopulation, the higher the value of the prevalence rate in said subpopulation, and vice versa.

The MSFI prevalence rate for the subpopulation of women with public or private employment (17.01, 90% MoE = 1.52), as well as that for the subpopulation constituted by housewives and students (16.93, 90% MoE = 3.06), were similar to the prevalence rate for the surveyed population. The MSFI prevalence rate for the surveyed women living in rural areas (18.13, 90% MoE = 2.83) was higher than the prevalence rate for all surveyed women, as was that for women who suffered a reduction in their income during confinement (18.31, 90% MoE = 2) and, particularly, for those who did not have resources for their personal expenses (29.53, 90% MoE = 3.21).

Despite having larger margins of error due to the smaller size of the subpopulations (

Table 1), the MSFI prevalence rate for women living in the Amazon region (21.37, 90% MoE = 4.24) and for women with three or more children (20.97, 90% MoE = 4.71) surpassed the prevalence rate for the surveyed population. Similarly, the prevalence rate of MSFI for women in the Ecuadorian Highland region (17.66, 90% MoE = 1.77), for women with primary/secondary education levels (17.26, 90% MoE = 1.77), for women who are married or in consensual union (17.36, 90% MoE = 1.63), and for women with 1 or 2 children (17.13, 90% MoE = 1.54) were slightly higher than the prevalence rate for the total women surveyed. In contrast, the MSFI prevalence rates for women residing in the Pacific Coast region (13.44, 90% MoE = 2.40), for women without children (12.63, 90% MoE = 3.57), for those who did not experience a decrease in their income (15.71, 90% MoE = 1.85), and for those who had resources for their personal expenses during confinement (12.47, 90% MoE = 1.40) were lower than the MSFI prevalence rate for the surveyed population. Likewise, the MSFI prevalence rates for women living in urban areas (16.63, 90% MoE = 1.55), for women with university studies (16.61, 90% MoE = 2.12), and for those who stated that they were single, divorced, or widowed (16.12, 90% MoE = 2.47) were slightly lower than those for the total women surveyed.

Discussion

This research provides evidence on the differences in MSFI among specific subpopulations of women in Ecuador in relation to the decrease in income during the COVID-19 confinement. This underscores the importance of studying vulnerable groups as a contribution to the formulation of more inclusive policies. In addition, it adds to increasing knowledge about other determinants of inequality in food insecurity among Ecuadorian women, whose intersection should be considered in future research. In this sense, the particularly severe situation faced by married women in rural areas and those in the Amazon region who lack financial resources for personal expenses highlights the relevance of empowering women (

FAO 2017a).

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of Ecuador managed the health crisis through a total of 58 health emergency declarations and orders. These measures included: the organization and strengthening of public and private health services with health infrastructure regulations; the diagnosis (rapid tests and PCR tests) and treatment of COVID-19-infected patients (including a toll-free telephone line); training and provision of financial incentives for health professionals; and the provision of supplies and coordination with other entities and institutions, such as fire brigades and provincial governments (

International Labor Organization 2021). The National Emergency Operations Committee was established to manage risks and take and execute actions related to COVID-19. This national measure has been criticized for lacking citizen participation in decision-making (

Torres and López-Cevallos 2021). Additionally, other immediate consequences of confinement on women, such as the increase in domestic violence (

Wake and Kandula 2022), have also been shown to be associated with MSFI (

Huq et al. 2021). The entire situation stemming from the pandemic resulted in an economic downturn related to the interruption of commerce, tourist activities, and the closure of companies (

León and Erazo 2021). The already unequal economic status of women is expected to further deteriorate following the pandemic worldwide (

UN 2020;

Bapolisi et al. 2021).

It is important to mention that, in 2020, the UN announced that 84% of single-parent households were formed by women (

UN-Women 2020) and that, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses of Ecuador, 69.2% of households in Ecuador could not afford the monthly cost of the Basic Family Basket (

Programa Mundial de Alimentos 2021). In addition, people's problems in meeting their nutritional requirements in Ecuador are related to the poorest income decile and to low protein consumption (

FAO et al. 2020). However, there is a scarcity of data on food insecurity in Ecuador disaggregated by sex or by other vulnerable groups—both in official data and in previous studies, which makes it difficult to quantify the problem of food insecurity among women. Based on our research, women experiencing income reduction and those lacking personal funds during the pandemic exhibited higher MSFI prevalence rates than their counterparts who did not experience income reduction or had financial resources for their expenses, respectively. These differences were found to be statistically significant. Thus, hunger and acute and chronic malnutrition will continue to be a problem and a burden on the economies of many countries (

FAO et al. 2020). However, as mentioned in previous research (

Pool and Dooris 2021), low income alone does not explain the prevalence of MSFI. That is why, despite the limitations of our data, we conducted an analysis on the recognition that gender equality could be a necessary and innovative concept and practice to improve MSFI, even more than income. Furthermore, the empowerment of women could have an important impact on the social determinants of health (

Ruiz-Cantero et al. 2019) and on the nutritional status of populations (

Sugawara and Nikaido 2014;

Cunningham et al. 2015), regardless of the economic situation of the household and the demographic characteristics of the population (

Engle 1993). In this sense, women can play an interesting role in the eradication of MSFI because of their participation in food production, in agriculture (

Ene-Obong et al. 2017), and in obtaining resources for their families (

Sarki et al. 2016), as well as because of their role in child and family well-being, through care in dietary diversity and feeding practices (

Larson et al. 2019). Proof of this was the important role that Ecuadorian rural women played in agriculture and marketing baskets with agricultural products for the population during the pandemic within the framework of the National Agricultural Strategy for Rural Women (

Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock of Ecuador 2020). However, our findings show higher values of MSFI prevalence in rural women, which denotes a divergence between their contributions to the population's food security and the challenges of proposing strategies to mitigate MSFI exclusively in them.

The condition of being a woman must also be accompanied by an analysis of its intersection with other social and maternal-infant dimensions. Thus, in our study, we found differences in the prevalence of MSFI among women from more vulnerable groups compared to more empowered women. A higher prevalence of MSFI was observed in women from the Amazon region compared to the Ecuadorian Highlands and the Pacific Coast regions. In this regard, the FAO, in its 2020 Report, conducted an analysis of the poor economic situation of the Amazon region, which could limit a healthy diet for its inhabitants (

FAO et al. 2020). We also observed that women in this study experienced a higher prevalence of MSFI in households with more than three children or adolescents. This result is consistent with a study conducted in Chile, where a higher number of children is shown as a risk factor for MSFI (

Giacoman et al. 2021). In 2020, the average number of children per woman in Ecuador was three (

INEC 2021). This could be an aspect of interest for public policies and their adaptation to this context. In addition, in our study, we found that being married may be a risk factor for a higher prevalence of MSFI, as marriage and the presence of young children could explain the low participation of women in the labor force (

UN-Women 2020).

However, a study conducted in Chile showed that, during the pandemic, female-headed households had fewer MSFI problems than male-headed households (

Giacoman et al. 2021). It has been observed that women tend to manage the resources better than men (

Larson et al. 2019) and, when they are the main contributors to household income, the risk of MSFI is substantially lower than when this role is assumed by the male partner or spouse (

Schmeer et al. 2015).

Finally, we found a high percentage of women who were concerned about not having access to healthy foods. The global trend in food security refers to the growing uncertainty that a healthy, balanced, and diverse dietary pattern is becoming increasingly costly. This is related to the high prevalence of undernourishment (12.4%) reported by the FAO for Ecuador in the period 2018–2020 (

Alle et al. 2021;

FAO 2022). Food insecurity is therefore not only synonymous with hidden hunger and acute and chronic malnutrition (

FAO et al. 2021a). Food insecurity can also have consequences for other aspects of people's health and well-being, for example, by causing negative psychosocial effects (

Ballard et al. 2014). The experience, fear, uncertainty, or anxiety of not having healthy food constitutes a serious problem in itself, as it indicates a violation of a human right, that is, having adequate food (

FAO 2018). In this regard, the impact of social norms that restrict the participation of married women in earning their own income should also be analyzed.

Limitations and strengths of the study

The main limitations of this study are, on the one hand, the use of non-probabilistic sampling—which prevents the generalization of our results to the population—and, on the other hand, the use of an online survey as a data collection technique—which could bias the information obtained; furthermore, online surveys face the challenge related to participant selection, given the difficulty in reaching certain demographic groups or engaging participants. This can result in a lack of representation of certain age groups, residential areas, or educational level groups. However, we show empirical evidence of the MSFI problem in a group of Ecuadorian women. Our study shows a MSFI prevalence rate of about 17% in a sample of Ecuadorian women as a pilot contribution to the monitoring of the SDG-2, with interesting differences by population subgroups. These data are similar to the figures shown by the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses of Ecuador (

Moreno et al. 2018). However, it should be noted that these figures were obtained before the pandemic situation, and the FAO has warned that these figures may be even higher nowadays (

FAO et al. 2021b).

It should also be noted that the application of the specific FIES module for the pandemic situation (

FAO 2020) was not possible, since our survey was conducted before this module was available. In any case, it would be advisable to incorporate the FIES into national surveys (preferably periodic ones). This would allow not only to obtain MSFI prevalence rates that could be inferred for the entire population, but also to analyze its evolution over time.

With a view to including the FIES module in future surveys, it would be necessary to study (prior to its application) whether there are problems of interpretation of the items that presented a high outfit and, if necessary, to reformulate them (in the case of this study, Skipped and Fewfood). In this sense, cognitive tests could be used to verify the level of understanding of the questions, both in their structure and in their order. These tests could be applied to population groups shaped according to the cultural and regional variability of the country. Cognitive tests use a qualitative method that focuses on the reasoning behind the respondents' answers and have been shown to improve understanding of questions on surveys (

Willis and Artino 2013).

Regarding the application of the FIES instrument, a 12-month reference period—with a previous linguistic and cultural adaptation—is recommended (

FAO 2018). This would allow a better understanding of the questions in the FIES. In this sense, as suggested by the FAO, the order of the questions in the survey should be, first, demographic or general questions, second, the FIES items, and, finally, those relating to economic characteristics.

To ensure a certain degree of success, future studies similar to this descriptive study of socioeconomic and geographic dimensions associated with food insecurity will be enriched with an intersectional analysis of these dimensions. Women's food insufficiency is related to vulnerability factors such as intersectional identities and disparities (

Moen et al. 2020). These include low income, resource management (

Belsey-Priebe et al. 2021), rural area of residence (

Benítez-Zapata et al. 2021;

VanVolkenburg et al. 2022), marital status (having a partner or not), and household composition (having children or not) (

Silva et al. 2023). These were some of the sociodemographic characteristics of this study that were related to MSFI. Other disparities that have been analyzed in previous studies, such as women as heads of household (

Negesse et al. 2020), low education (

Grimaccia and Naccarato 2020), skin color (Afro-descendants) (

Santos et al. 2023), and household composition that includes older adults (

Silva et al. 2023), highlight the relevance of the intersectional perspective. This perspective can contribute to identifying elements that perpetuate exacerbated health inequalities when combined with other disparities and specific conditions of vulnerability.

The term intersectionality refers to the critical idea that race, class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nationality, ability, and age do not operate as unitary and mutually exclusive entities. Instead, they are interrelated phenomena that are reciprocally constructed (

Crenshaw 2013)). Understanding the historical aspects of gender discrimination could help ensure that discrimination against women is not seen as an isolated problem; therefore, addressing the issues of MSFI in women must consider their own particularities (

Crenshaw 2013;

Peek et al. 2020). Health risks related to food insecurity, concern for future generations, and the burden of gender responsibility, including gendered responsibilities for domestic and care-giving roles (

Izquierdo 2003), as well as gendered cultural expectations about food stewardship, may contribute to food anxiety among women. Within the medium- and long-term strategies considered to attain women's food security, emphasizing education is particularly valuable. Studies have demonstrated education's role in mitigating the effects of MSFI (

Grimaccia and Naccarato 2020), analyzed within interconnected factors like income and motherhood, which significantly influence access to education. To this end, the Ecuadorian State has the

Organic Law of Intercultural Education (2011), which, among other objectives, aims to promote policies, programs, and resources directed towards women who have lacked access to education or are educationally disadvantaged.

In Ecuador, similar to other ethnically diverse countries, Indigenous women's knowledge might have a positive correlation with dietary diversity, enjoyment of food, cultural practices, and nutrition (

Kuhnlein 2017). Nevertheless, Indigenous nationalities in Ecuador have endured centuries of discrimination, with inequalities being more pronounced among women. Moreover, the various ethnic groups in the country face sexist behavior that undermines their autonomy. Interventions aimed at reducing MSFI should involve empowering women, minimizing occupational segregation, and enhancing resource redistribution (

Silva et al. 2023;

Nchanji et al. 2023), while incorporating cultural aspects that encompass an understanding of the agricultural and peasant worldview.

We conclude that, in the group of Ecuadorian women who formed part of this study, there were inequalities in food insecurity during the decline in income associated with the 2020 confinement. These inequalities were based on their socio-demographic and economic characteristics. The most severe situations of food insecurity stem from being married, living in rural areas or in the Amazon region, and having no money for personal expenses. Given the need for urgent interventions, we encourage further research to be conducted to enable state policymakers to identify the intersections between women's economic and sociodemographic characteristics and their impact on food insecurity. This will enable monitoring the results of programs and interventions with real-time data, which will ensure the functioning of food systems and strengthen effective social safety nets to safeguard food security, as well as women's empowerment in society.

To achieve SDG-2, Ecuador needs to implement a series of public policies and strategies. These strategies should focus on enhancing and strengthening the efficiency and diversity of productive systems to contribute to the variety of the Ecuadorian diet (Availability). Additionally, it is crucial to strengthen sustainable policies that support family and peasant economies, such as the National Agricultural Strategy for Rural Women, to mitigate the inflation affecting Ecuador's population (Access). Furthermore, actions must also be planned to counteract the consequences of natural phenomena and anthropogenic actions, such as deforestation and forest fires (Stability). The implementation of food and nutrition education programs is also essential (Use) (

Aulestia-Guerrero and Capa-Mora 2020;

Community of Latin American and Caribbean States 2020).