Introduction

Ontario has eight extant species of native turtles, all of which are listed as species at risk by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). The Greater Toronto Area (GTA) has five native turtle species that can still be found in its wetlands despite being Canada’s largest urban aggregation (

Dupuis-Desormeaux et al. 2021). These include one threatened species, the Blanding’s Turtle (

Emydoidea blandingii) and four species of special concern: (1) the Midland Painted Turtle (

Chrysemys picta marginata), (2) the Snapping Turtle (

Chelydra serpentina), (3) the Northern Map Turtle (

Graptemys geographica), and (4) the Eastern Musk Turtle (

Sternotherus odoratus) in addition to the non-native Red-eared Slider (

Trachemys scripta elegans) (

Dupuis-Désormeaux et al. 2019).

The urbanization of the GTA has led to an 85% loss of its historical wetlands (

Whillans 1982) and fragmentation of the remaining wetlands that feed the northern shore of Lake Ontario. GTA municipalities, such as Brampton, are designated as urban growth areas and have seen rapid expansion of their population (estimated at 13% between 2011 and 2016;

Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing 2019). The accompanying housing and road development has further fragmented the landscape and led to turtle road mortality and skews in sex ratios (

Gibbs and Steen 2005;

Dupuis-Désormeaux et al. 2017).

Over the last decade, Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) staff have been engaged and working with volunteers to walk along areas around Heart Lake Road in Brampton and its surrounding provincially significant wetland complex to document wildlife road mortality. Concerned community members conducted years of road mortality surveys that eventually led to installation of various mitigation measures, including exclusionary fencing, dedicated under-road wildlife passages, and protected turtle nesting beaches along the Heart Lake Road in Brampton (

Dupuis-Désormeaux et al. 2024).

The coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused daily routines to be disrupted, people were encouraged to work from home if possible, and many indoor activities were curtailed or cancelled. As a consequence, the usage of urban parks increased both in Southern Ontario (

Borkenhagen et al. 2021) and globally (

Geng et al. 2021)

. A similar phenomenon was taking place in Brampton, where in 2020, a group of turtle enthusiasts founded the Heart Lake Turtle Troopers (HLTT) and created a private Facebook group on which residents could post turtle photos, discuss issues and feel-good stories (such as moving a turtle off the road), and share turtle-related ideas. In late 2020, the HLTT approached TRCA to ask how they could become further involved in volunteer activities to help local turtles. Due to the restrictions of COVID-19, the increased visibility of the mitigation measures previously implemented along Heart Lake Road (Dupuis-Desormeaux et al.

2024), combined with recent local press coverage about citizen involvement in the protection of turtles, HLTT quickly grew to over 500 people with many local residents looking for ways to become involved in turtle-protection activities. A small subset of 29 people from the HLTT followers became active volunteers and were trained by TRCA in 2021 and every subsequent year. In the past, TRCA staff had documented turtle nest locations by locating signs of nest predation during weekly surveys but without much success at finding a freshly laid nest that predators had not yet taken. To protect a turtle nest, especially in areas with high densities of subsidized predators, the observer must be in a position to secure a protective structure over the nest soon after the nesting turtle has left of nesting site. Returning the next day or even a few hours later is usually not sufficient to ensure that the nest will not have been depredated. Engaging and training a large group of dedicated turtle watchers can lead to a great increase in the chances of detecting a nesting turtle.

In this study, we report on the number of turtle nests protected in 2021 and 2022 at our monitoring site. For 2021, we also report on the success of the nest protection as measured by number of observed hatchlings, number of egg shells in the nest cavity, number of unsuccessful eggs, number of dead hatchlings found in the nest cavity, and number of rescued hatchlings and eggs that were taken to the Ontario Turtle Conservation Centre and subsequently released back into local wetlands.

Materials and methods

Monitoring site

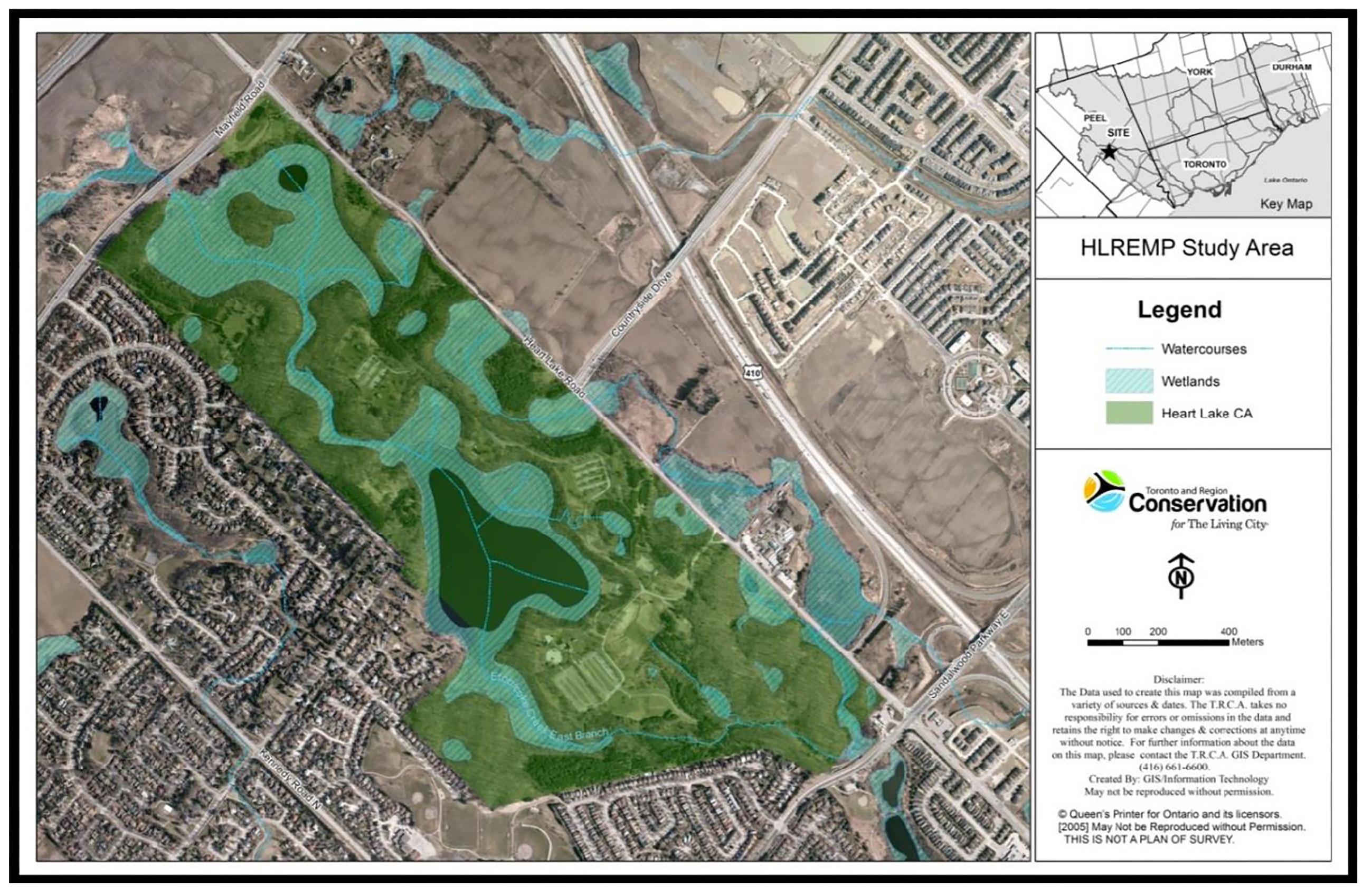

The various nest sites were located within the Heart Lake wetland complex in Brampton, Ontario, Canada (43°44′27″N, 79°47′29″W) and included sites at the Heart Lake Conservation Area, Loafer’s Lake, Donnelly Park, Professor’s Lake, and many other areas near small wetlands that are fed by various branches of the Etobicoke Creek (

Fig. 1).

Training

TRCA recruits and trains volunteers annually for a variety of volunteer programs, and these recruitment and training sessions are typically delivered in person at TRCA offices and/or on project sites. However, due to COVID-19 concerns and protocols in 2021, volunteer recruitment and training activities during this time were delivered virtually.

During April 2021, TRCA staff hosted several 1.5 h virtual volunteer recruitment sessions. Following the recruitment sessions, participants were provided with registration links to register as a TRCA volunteer and sign up for the various Citizen Science Volunteer Program (CSVP) activities. The volunteers that signed up for the turtle nest protection and monitoring activities were invited to attend one of two follow-up 1.5 h virtual sessions during which staff provided training on safety protocols, turtle species, and turtle nest identification in addition to discussing monitoring and data collection protocols. These same volunteers were trained to access a variety of digital tools to assist with scheduling volunteers, tracking turtle sightings, nest box installations, and recording volunteer efforts.

Data collection

The volunteer observations and nesting structure installation were managed and mapped using a customized survey geographic information system (GIS) tool that was developed through ArcGIS (Survey123 application), a subscription-based data gathering application that allows the user to collect data via web or mobile devices even when disconnected from the internet and upload data securely for further analysis. Staff trained volunteers to look for nesting turtles during the peak season (late May to early July). Once a turtle was detected on land, the volunteers followed it to its nesting area and watched the turtle from a distance (approximately 10 m, depending on the line of sight and local conditions) for as long as required until the female had finished laying her eggs and safely returned to the wetland. As this process could be spread over many hours, volunteers alternated if necessary. Volunteers also kept curious people and dogs at a safe distance from the turtle laying her eggs, thus ensuring minimal disruption to the turtle. After the laying female had returned to the wetland, the volunteers placed a 60 cm × 60 cm nest protector over the nest and anchored it on the corners with 30 cm galvanized nails (see

Fig. 2).

Volunteers marked the nest protector with a unique number identifier. They also noted the date, time, turtle species, and specific location (using ArcGIS Survey123) of each nest in a shared database. TRCA purchased and built nest protectors out of wood and galvanized steel mesh, and the City of Brampton built lockable storage boxes to house these protectors and some of the equipment (mallets, 12 in. nails, flagging tape, and permanent markers). The wetland sites were monitored in an ad hoc manner by volunteers, and nests were discovered at all times of the day.

The volunteers monitored the protected nests regularly (weekly during incubation and daily as the expected hatch date approached). The volunteers searched for signs of emergence holes, hatchlings, and/or predation. To report on nesting success, 6–8 weeks after the expected emergence period, nests were excavated to look for signs of successful hatching (eggshells inside the nesting cavity and/or emergence holes) or unsuccessful incubation (infertile eggs, desiccated eggs, rotting eggs, eggs penetrated by plant roots, and/or dead hatchlings inside the nest cavity or under the nest protection device). Snapping Turtle nests were excavated in November 2021, and Midland Painted Turtle and Red-eared Slider turtle (RES) nests were excavated in late May 2022 (as both these species are known to overwinter inside the nest). Trained volunteers who found suspected nesting sites (showing signs of nesting such as mounds of fresh mud) without visual confirmation of a nesting turtle would verify the suspected nest site by carefully digging the area with hand tools until the appearance of the first egg. Upon egg discovery, they re-covered the egg and installed a nest protector. Permitted volunteers also removed eggs that had been laid in active construction sites or other areas of immediate danger to the nest and moved those eggs (under Permit Authorization No. 1100266) to the Scales Nature Park (a registered incubating facility for turtles).

Results

In 2021, we documented 180 nests (105 nests were discovered because they had already been predated) and were able to place protection on 75 of these (34 Snapping Turtle, 36 Midland Painted Turtle nests; see

Table 1) using the predator-excluding devices. Although Red-eared Slider turtles are not native to our area and thus are not part of the turtle nesting protection program, volunteers also inadvertently protected five Red-eared Slider nests in 2021.

In 2022, 165 nests were discovered (55 nests had their eggs extracted from the nest and sent for incubation), and 100 were protected on site with a nest protecting device.

Snapping Turtle nests

In 2021, volunteers protected 34 Snapping Turtle nests. Excavation of the nests found 665 hatched Snapping Turtle eggshells with 10 live hatchlings discovered during nest cavity investigations. Clutch sizes ranged between 17 and 57 eggs with an average clutch size of 36 eggs (standard deviation = 10.8). We measured the success rate for nests by dividing the number of hatched turtle eggshells inside the nest by the total number of eggshells, eggs, and dead hatchlings discovered inside the nests. The success rate averaged out to be 71.1%, with 157 infertile eggs found in the nest cavities in addition to 67 dead hatchlings stranded in nest cavities (n = 10). During nest inspection, 72 eggs that had not hatched and did not appear to be damaged were discovered inside the nest cavities. These eggs were sent to the Ontario Turtle Conservation Centre in hope of incubating the turtle embryos. Out of these 72 eggs, only one egg was successfully incubated, and the hatchling was released back into the wetlands in the spring of 2022. In 2022, 73 Snapping Turtle nests were protected. Because we felt that we had sufficient data from 2021 to gauge the success of the nest protection program, we did not excavate nests in the fall of 2022 to count eggshells.

Midland Painted Turtle nests

In 2021, volunteers protected 37 Midland Painted Turtle nests. Clutch sizes ranged between 4 and 11 eggs with an average clutch size of 6.5 eggs (standard deviation = 1.8). Of the nests protected, 81 empty eggshells were discovered. However, upon excavation, 38 eggs had not hatched (either infertile or desiccated), and 26 hatchlings were found to have died inside the nest cavities (n = 8) or had become tangled in grass roots and blades (n = 1). In 2022, 65 Midland Painted Turtle nests were protected.

Red-eared Sliders

In 2021, five RES nest sites were protected inadvertently with four nests having fertilized eggs. During excavation (May 2022), we found eggs with arrested late-stage embryonic development. Clutch sizes ranged between 8 and 13 eggs, and no signs of hatchling success in any RES nests for that year were detected. In 2022, nine RES nests were protected at two different sites, and one nest had hatchlings that were found upon egg extraction (

Dupuis-Désormeaux et al. 2022).

Eastern Musk

In 2022, an Eastern Musk turtle was discovered laying eggs. The nesting turtle laid seven eggs along a busy cycling path, and her eggs were rescued and moved for incubating. Five eggs hatched at the Ontario Turtle Conservation Centre, and the hatchlings were released back into the wetlands later in the summer of 2022.

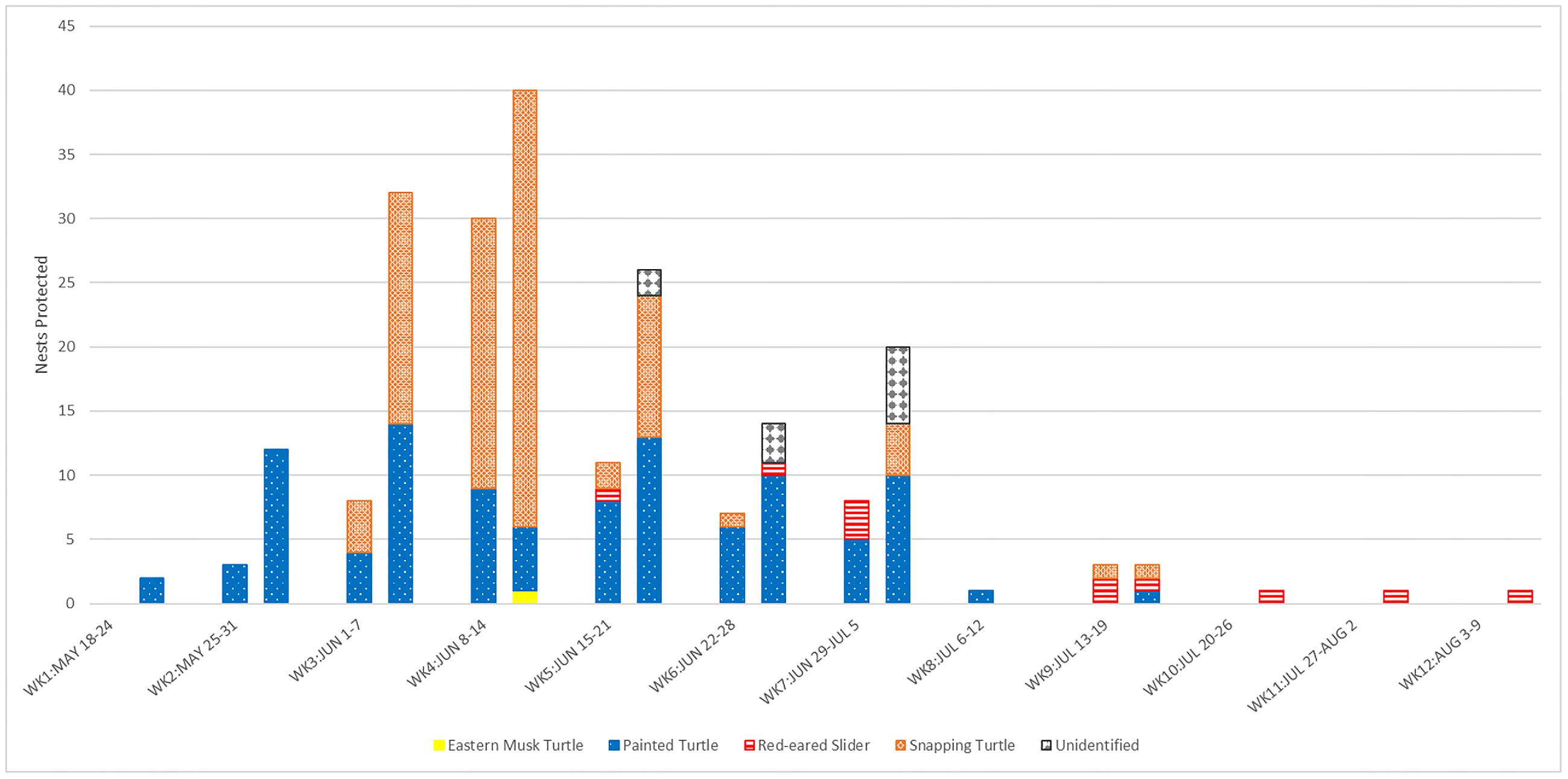

We found that turtles at our site started nesting in 2021 on May 25 (Painted) until July 16 (Snapping), and in 2022 on May 21(Painted) until August 5 (RES) (

Fig. 3).

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all the followers and volunteers of the Heart Lake Turtle Troopers who worked vigorously to protect and monitor nesting site, and specifically the organizational work done by Jamie-Lee Ball, Christina Cicconetti, Lori Leckie, Leah Nacua, and Rebecca Zimmerman. We are indebted to Scales Nature Park for their financial support, expertise, and help with removing eggs and incubation under permit (Permit Authorization No. 1100266). The authors would also like to thank Dr. Sue Carstairs and the volunteers and staff at the Ontario Turtle Conservation Centre for training in addition to their frequent help with injured turtles and egg incubation. Finally, we would like to thank the Volunteer Turtle Taxi Drivers that ferried eggs and hatchlings from various locations.