Access to Environmental Justice in Canadian environmental impact assessment

Abstract

Contemporaneous reforms to Canada and British Columbia's environmental impact assessment legislation have the potential to advance Access to Environmental Justice. Access to Environmental Justice is the ability of individuals and communities who are disproportionately and negatively impacted by environmental decisions to access legal and regulatory processes and to have their concerns heard and addressed through environmental decision-making and dispute resolution. Access to Environmental Justice connects concepts of environmental justice, public participation, the rule of law, and access to justice to provide a framework for evaluating the implementation of environmental impact assessment laws. We conducted a preliminary analysis of early implementation of legislative reforms in Canada and British Columbia. Our analysis indicates that a number of factors influence who is seeking to access environmental justice through environmental impact assessment, including geography, project type, and the availability of a legislative mechanism that allows anyone to request an assessment. Whether Canada and British Columbia's reforms are advancing Access to Environmental Justice requires continued analysis as projects continue to be assessed under the new laws.

1. Introduction

Environmental impact assessment (EIA) is a central decision-making tool in Canadian environmental law, used by governments to evaluate, decide upon, and justify approvals for major projects, such as mines, dams, pipelines, and highways, each with wide-ranging ecological and social impacts.1 Public participation and engagement with affected communities and Indigenous Peoples are widely understood as enduring, if imperfect, features of EIA law (O'Faircheallaigh 2010). Unlike other forms of environmental regulation in Canada, such as permitting which occurs largely without the scrutiny of the public eye, EIA is, in principle, an important site through which the public and Indigenous Peoples may engage directly with decision-makers and project proponents and have meaningful impacts on environmental and resource decision-making (Glucker et al. 2013; Stacey 2020).

This vision of EIA as contingent upon active and meaningful engagement with affected communities was reinforced by British Columbia and Canada during the major reform processes leading to their respective 2018 and 2019 EIA statues.2 Canada's reform process committed to “rebuilding trust in the system” in response to criticism of the existing limited opportunities for public participation, challenges for the public and Indigenous Peoples in accessing information, and inadequate explanations for the final decisions (Canada 2017b; Jacob et al. 2018). Similarly, BC states that its “revitalization” of EIA has “[e]nhanc[ed] public confidence by ensuring impacted First Nations, local communities and governments, and the broader public can meaningfully participate in all stages of environmental assessment through a process that is robust, transparent, timely and predictable” (2018, 8). As of 1 February 2023, 22 project proposals are being assessed under the federal Impact Assessment Act, SC 2019, c 28 (IAA), and 11 project proposals are being assessed under BC's Environmental Assessment Act, SBC 2018, c 51 (EAA). Many more proposals have still been subject to requests for designation, as we describe below. While we still await the first completed EIAs under the new regimes, we can nonetheless observe their early implementation and begin to assess whether the reforms are achieving their stated aims.

To do so requires a clear understanding of the aims that animated the law reform process and how these have ultimately crystallized into opportunities for individuals and communities to access EIA. In this paper, we identify Access to Environmental Justice as an overarching aim of the reform processes leading to the IAA and EAA, and we provide an early analysis of how these new statutes are meeting this aim. Access to Environmental Justice means the ability of individuals and communities who are disproportionately and negatively impacted by environmental decisions to access legal and regulatory processes and to have their concerns heard and addressed through environmental decision-making and dispute resolution. To illustrate Access to Environmental Justice in EIA and to begin to evaluate how the new legislation furthers this goal, this article provides initial baseline data on who has accessed BC and Canada's new regimes and how they have sought to be heard.

In Part Two, we define and explain Access to Environmental Justice in relation to four related legal and interdisciplinary concepts: environmental justice, public participation, the rule of law, and access to justice. While some or all of these concepts may be familiar to EIA researchers and practitioners, we distill from each concept its distinct contribution to EIA and explain how all four work together to support Access to Environmental Justice. Part Three describes the materials we relied upon, our methods, and the definitions we devised to assess who is accessing EIA and how. In Part Four, we present our findings, highlighting factors that seem to influence who is seeking to access environmental justice through EIA, including geography and project type. We observe that expanded access to requests for designation—the ability for anyone to request an assessment—appears to be an important site for accessing environmental justice. Finally, we identify information gaps related to key reforms and identify issues in need of further study.

A preliminary empirical analysis such as this always invites more questions than it answers. Our objective is to bring a fresh perspective to EIA law by defining Access to Environmental Justice, showing how it explains recent law reform, and demonstrating how Access to Environmental Justice may be used to evaluate EIA regimes in practice. By combining techniques of legal interpretation and empirical analysis, we provide early insights into the implementation of BC and Canada's EIA legislation on the ground.

1

The terminology for assessment regimes varies across jurisdictions. BC uses ‘Environmental Assessments’, whereas the Federal scheme refers to ‘Impact Assessments’ to denote the broader range of social and health impacts that major projects may have. Throughout this paper, we use the acronym EIA to refer to both.

2

A note on terminology: legislation, statute, and Act are all synonyms and will be used interchangeably. ‘Law’ is a more encompassing term that includes the whole body of binding rules and principles for EA: legislation, regulations, regulatory decisions, and judicial decisions.

2. Access to Environmental Justice

Access to Environmental Justice is the pursuit of environmental regulation and dispute-resolution mechanisms that are, in actuality, accessible and responsive to individuals and communities who disproportionately experience environmental risks, harms, and benefits. We explain Access to Environmental Justice as the intersection of four distinct but often interrelated concepts that underpin EIA: environmental justice, public participation, the rule of law, and access to justice. While each of these concepts is individually the subject of extensive scholarship, EIA effectively highlights their interrelatedness both in theory and in practice. We take our cue from the expert panel convened in the federal reform process, which wrote:

“[t]he assessment process can contribute positively to a project's social license if, and only if, that process takes into account the concerns of all parties who consider themselves or their interests to be affected by that project. The exclusion of individuals or groups from the assessment process erodes any sense of justice and fairness… the new assessment process must be inclusive” (Canada 2017a, n.d., 13–14).

This passage encapsulates four related concepts. The connection between justice, fairness, and social license all link to environmental justice, the notion that environmental laws should instantiate substantive equality and not perpetuate disproportionate environmental risks and burdens on marginalized individuals and communities. The notion that decision-makers should hear and consider the concerns of those affected is addressed by the theory and practice of public participation. The expert panel's concern about excluding individuals and groups and its emphasis on inclusivity link to the concept of access to justice, which addresses the barriers within the legal system that impede equal access to legal processes and dispute resolution mechanisms. Finally, in noting that justice and fairness flow from taking into account the concerns of those affected, the panel draws on the rule of law, a core legal value that includes the right to be heard. Below, we address each of these concepts in turn.

2.1. Environmental justice

Environmental justice describes a constellation of ideas, scholarship, and social movements that identify and challenge existing laws and institutions that reproduce an unequal distribution of environmental benefits, harms, and risks (Gonzalez 2015; Chalifour and Scott 2020, 155). Environmental justice responds to problems such as environmental racism and violence, in which marginalized communities “bear disproportionate and often devastating impacts [of] the conscious and deliberate proliferation of environmental toxins and industrial development” (Women's Earth Alliance and Native Youth Sexual Health Network 2016, 13–15; Bullard in Gosine and Teelucksingh 2008, 4). While early environmental justice movements emerged from the struggles of Indigenous and racialized communities, environmental justice scholarship and activism have expanded to include demands for equality across a variety of identity markers, including gender, socio-economic status, and disability (Young 1983; Bullard and Johnson 2000; Gosine and Teelucksingh 2008, 21; Jodoin et al. 2020, 104–11; Chalifour and Smith 2010, 510–12; Scott 2014, 300–302). Through the close intertwining of theory and grassroots organizing, environmental justice brings a critical perspective to environmental law reforms, which—even despite promising aims—may reinforce existing societal inequalities (Scott 2014).

A guiding tenet of environmental justice is “we speak for ourselves”—a recognition that individuals and communities have knowledge, experience, and agency, and must have a role in decision-making that affects their interests (Agyeman et al. 2010, 4–5). Environmental justice scholars and advocates thus ask of environmental and resource decision-making: “[w]hose voices have been heard, whose have been silenced?” (Agyeman et al. 2010, 5). They have identified three interrelated dimensions of environmental justice—its substantive, procedural and recognition dimensions—that help to answer these questions, each of which is engaged through EIA (Schlosberg 2003; Chalifour 2015, 97).

Substantive justice refers to the equitable distribution3 of environmental risks and benefits across society (Chalifour and Scott 2020, 63–65). Disproportionate burdens of toxic pollution and inequitable access to urban green spaces are two well-studied experiences of environmental injustice (Chalifour and Scott 2020, 64). Procedural justice refers to equality of access to information, processes, and remedies for environmental decisions (Young 1983; Chalifour 2015, 96). Finally, recognition concerns who is “seen” by decision-makers as potential recipients of environmental benefits or burdens and whose knowledge is considered in shaping outcomes (Chalifour 2015, 96–97). It also speaks to deeper, systemic issues intrinsic to colonial governance systems in which the perspectives, knowledge, and participatory rights of affected communities are degraded and devalued, laying the groundwork for substantive injustices to be wrought (Schlosberg 2004, 518–19; Booth and Skelton 2011; Whyte 2011). Indigenous legal orders and worldviews contain distinct understandings of environmental justice, which cannot simply be subsumed within environmental justice conversions dominated by western perspectives (Whyte 2011; McGregor 2018).

EIA is a legal framework that blends substantive, procedural, and recognition dimensions of environmental justice. As a key decision-making point for major project development, it culminates in the allocation of benefits, risks, and burdens across society, including environmental impacts. For instance, approvals of oil sands developments allocate substantial benefits to proponents and disproportionate environmental harms to neighbouring and downstream First Nations (Gosine and Teelucksingh 2008, 37–41; Chalifour et al. 2009; Women's Earth Alliance and Native Youth Sexual Health Network 2016). The outcome of EIA is, in principle, shaped by the process for the assessment of environmental impacts and whose concerns are heard within that process. Relatedly, the very structure of EIA engages the recognition dimension of environmental justice: certain knowledges and worldviews fit more easily than others into western science and common-law frameworks for assessment and decision-making. Moreover, ultimate recognition comes from decision-making authority and enforcement, which in the Canadian legal system is generally a provincial or federal government. These three dimensions of environmental justice provide a framework for critique of EIA and, given past practice, invite skepticism about whether law reform can actually achieve environmental justice (Young 1983; Chalifour and Scott 2020, 76–77, 83–88).

3

Equitable and equal are distinct concepts. Equal references to the allocation to recipients of the same resources. Equitable refers to an allocation that matches the distinctive features of recipients so as to reach an equal outcome. See, e.g., Daniels (2017).

2.2. Public participation

Public participation is described by the International Association on Impact Assessment as “the involvement of individuals and groups that are positively or negatively affected, or that are interested in, a proposed project, programme, plan, or policy that is subject to a decision-making process” (André et al. 2006, 1). Improving public participation is nearly unanimously considered a positive in the design of EIA systems (O'Faircheallaigh 2010, 19; Glucker et al. 2013; Noble 2015, 218). The expert panel on Canada's EIA law reform, referenced above, found that “[m]eaningful public participation is a key element to ensure the legitimacy of IA processes. It is also central to a renewed IA that moves IA towards a consensus-building exercise, grounded in face-to-face discussions” (Canada 2017a, 36).

O'Faircheallaigh explains that there are at least three common objectives for public participation in EIA (O'Faircheallaigh 2010). First, members of the public can provide important information about the proposal (for example, about local impacts) that decision-makers need to make the best possible decision. Secondly, public participation in decision-making en\hances the democratic legitimacy of EIA decisions. Third, public participation can “reframe[e] decisions [and] shift the balance of power” by challenging the existing framework for EIA processes and decision-making (Armitage 2005, 246–249; O'Faircheallaigh 2010, 22–24). For example, groups who are marginalized by state-led assessment processes may conduct their own EIA, reframing decisions and challenging the legitimacy of the state-led decision-making process (O'Faircheallaigh 2010, 23; Tsleil-Waututh Nation 2015; Nishima-Miller and Hanna 2022; Sankey et al. 2023).

Just as there are multiple objectives of participation, there are multiple constituencies within the “public” itself (Glucker et al. 2013, 109; Noble 2015, 200–202). Noble suggests that one way to distinguish between these constituencies in EIA is to consider the stakes that different groups have in the outcome of an assessment, along with their potential for influence on that outcome (Noble 2015, 200–204). Residents near a proposal site may have high stakes in the assessment results but low influence since many residents tend to be uninvolved in environmental planning. Equally important is who sits outside of these public constituencies. Indigenous Peoples exercise rights to self-determination and self-government, an important relational difference (UNDRIP 2007, arts 3–4). While some approaches discussed in the context of public participation may also be suitable in the context of Crown engagement with Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous Peoples acting through representative institutions do not engage with EIA on the same sovereign-subject basis as the public. They do so through government-to-government relationships (whether or not they are treated as such by Canadian governments) (Nichols 2018, 96–100).

Disentangling these multiple aims, governments, and publics starts to show how realizing “meaningful” public participation, as described during EIA reform processes, will be complex and contested. However, the following general points can be observed from the literature. First, meaningful participation requires that the public, at the very least, enjoy a level of involvement greater than tokenism; i.e., non-participation veiled as placation or mere access to information without the ability to effect outcomes (Arnstein 1969, 216–17). Second, and relatedly, meaningful participation entails early participation, which enables input and the possibility of influence on the process and the decision (Hartley and Wood 2005; Noble 2015, 237; Hanna and Arnold 2022, 16). Third, meaningful participatory processes must account for the fact that the public does not simply lie ready and waiting to engage in EIA. Rather, proactive educational, capacity-building, and engagement work will be needed by government agencies (Noble 2015, 221–22, 237). Finally, while governments might seek to reserve the final say of an assessment for themselves, it is meaningful participation that ensures the accuracy and legitimacy of decision-making (Beierle and Cayford 2002, 74; O'Faircheallaigh 2010, 22; Noble 2015, 218). Governments need the public to participate. Here, public participation crosses over with the rule of law, a concept that similarly emphasizes the importance of a fair process to generate lawful and legitimate decisions.

2.3. Rule of law

The rule of law describes a core commitment of democratic legal systems—that the exercise of public power should be constrained by legal norms and not subject to the whims of those in positions of power. For example, a person applying for a passport should know that a government official will consider the same factors and apply the same rules to their application as to any other.

While the concept of the rule of law is endlessly debated in legal and political theory (Waldron 2002), we can identify three accepted components that are important for understanding its relevance to the Canadian EIA (Liston 2017, 144; Stacey 2020). First, no one is above the law, not even the state. Both individuals and government officials alike are subject to the law. Second, in the Canadian context, the Supreme Court of Canada has specified the rule-of-law requirements for governmental decisions—such as passport decisions and EIA approvals (Canada v. Vavilov 2019, Baker v. Canada 1999). Government decisions must be made using a fair process that allows those subject to the decision to “know and respond to the case against them”, and for those decisions to be reasonable ones, supported by reasons of fact and the relevant law (Baker v. Canada 1999). Finally, the rule of law requires effective mechanisms for holding governments accountable when they do not fulfill these requirements. Courts or other independent arbiters must be available to determine whether these legal standards are met if a decision is perceived to be unfair or unreasonable (Bingham 2011, 90–96; Liston 2017, 144).

In this way, the rule of law is about compliance with the principles of fairness and the applicable legislation. This means that a court or other arbiter will not generally inquire into whether the government decision was, on its own, a good or wise policy decision. Instead, Canadian courts demand reasons for government decisions that demonstrate it has properly accounted for the relevant facts and governing laws (Canada v. Vavilov 2019). These requirements of a fair process and reason-giving promote transparency and accountability in government decision-making (Canada v. Vavilov 2019; Daly 2016).

Environmental law scholars have noted the connection between EIA and the rule of law. Fisher describes EIA as providing “procedure in the public interest” (Fisher 2016, 425). EIA blends the rule of law's requirements of fairness and the right to be heard with the concept of public participation (see also: Hartley and Wood 2005). Through EIA, it is not just the proponent who can claim these rights but also the public broadly. Further legislative requirements on what must be assessed and how these factor into decision-making directly shape what is a reasonable decision. Compliance with these legislative requirements is an aspect of the rule of law and, thus, the lawfulness and authority of the decision. EIA provides a framework for those affected by the decision to see what information was taken into account and the basis on which the decision was made. Accordingly, decisions that appear deficient can be challenged in court for their compliance with the law. This EIA requirement of reasoned, public decision-making contributes to upholding the rule of law.

The concept of the rule of law is complicated in a landscape of legal pluralism. Federal and provincial laws have been layered onto pre-existing Indigenous legal orders, which have their own processes and standards for authoritative decision-making (Borrows 2010, 6–7). While Canadian courts often insist that the rule of law must mean settler law, especially in resource conflicts (e.g., Platinex Inc. 2006, Coastal GasLink Pipeline Ltd. 2019), Canada and British Columbia's commitments to implementing the UN Declaration on the Right of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP 2007) require this assumption to be replaced by the understanding of Canada as a place of multiple co-existing legal orders (Nichols and Morales 2021; Lindberg 2022, 55). Embracing this reality requires a rule of law that provides an overarching framework for “a fruitful, workable, ongoing discussion and cooperation between distinct legal orders” (Scott and Boiselle 2019, 277–78). While BC and Canada's EIA laws are very much settler laws, both reference the UN Declaration and were enacted with the stated purpose of improving the legitimacy and accountability of EIA decision-making in both settler and Indigenous communities (Wright 2020).

2.4. Access to justice

Finally, Access to Justice (A2J) concerns making the legal system, in fact, available for everyone in society. A2J takes a “people-centred approach”, by focusing on the beneficiaries of the legal system. The ability to access courts and expensive legal services is a pressing concern of A2J literature. As former Supreme Court Justice, Thomas Cromwell once quipped, “[m]any of my lawyer friends freely admit that they could not possibly afford their own services” (Cromwell 2012, 40). An inaccessible legal system means that many problems go unresolved, sometimes with devastating consequences. For example, a parent may not seek joint custody of their children in a contentious divorce due to inadequate legal support, even though joint custody may be in everyone's best interests (McLachlin 2008). Barriers to accessing justice align with other forms of discrimination in society, tracking identity markers of Indigeneity, gender, race, disability, socioeconomic status, etc. (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls 2019, 185).

However, A2J ideally is about more than basic access to courts and lawyers. It also involves the empowerment of individuals to engage with the legal system and law-making in broader ways that allow laws to become more responsive to society's requirements of justice (Macdonald 2001, 318–20; Farrow 2013, 983–84).4 As Macdonald describes, the real challenge of A2J literature and movements is “[h]ow do we give as much emphasis to the “justice” component of the phrase “access to justice” as we do to the “access” component so that citizens will actually want to pursue justice?” (Macdonald 2001, 320). A2J seeks to rectify inequalities and enhance citizen engagement in the law through practical reforms that, for example, reduce the cost of legal services, improve public knowledge of the law and legislative procedure, simplify court and tribunal processes, and accommodate a range of physical, mental, language, and other capacities within legal institutions (Hughes 2008, 777–81). Reforms to legal practice as well as designing new institutions, with equal access at the fore, are leading responses to the access to justice crisis. For example, the online forum and simplified process of BC's Civil Resolution Tribunal provides resources and support that empower individuals resolve their own legal issues related to small claims, strata property and some motor vehicle accidents without the assistance of a lawyer (Salter 2017). For Indigenous Peoples, access to justice entails revitalizing Indigenous laws, processes and institutions for dispute resolution on their own terms (Friedland 2014; Sankey et al. 2023).

Issues of A2J arise within EIA. Despite laudable aims of public participation and collaboration with Indigenous Peoples, the reality on the ground is often quite different. EIA, as a multi-staged and formalized decision-making framework, is designed principally for sophisticated, repeat users: the government decision-maker (Taylor 1984) and proponents (Murray et al. 2018). Research on EIA has highlighted the “cognitive inaccessibility” of mountains of EIA documentation and legislation due to obtuse and technocratic language unintelligible to non-experts (Sinclair and Diduck 2015, 79). Yet even those mountains of information are incomplete. For instance, a study of the South Saskatchewan River found that a quarter of the sampled EIAs from the region had incomplete documentation on public registries or referred readers to technical reports that were not publicly accessible (Ball et al. 2013, 471, 477). A study by Findlay also found that requests to obtain documents from EIA agencies often went unanswered or resulted in “endless redirections” (Findlay 2010 in Noble 2015, 224). Parallel issues of access—from fundamental design to bureaucratic practice—arise in EIA as in the legal system more generally.

4

In this respect, the issue of access to justice as it intersects with Indigenous Peoples has additional layers. The Canadian legal system is set up in ways that exclude Indigenous laws and worldviews and that actively discriminate against and perpetuate colonial harms (Iacobucci 2013, Friedland 2014).

2.5. Access to Environmental Justice

Access to Environmental Justice connects environmental justice, public participation, the rule of law, and A2J. All four concepts are closely interlinked in the EIA. As a legal framework requiring transparent, fair, and reasoned decisions, EIA has the potential to render inclusive decisions that advance environmental justice and hold governments to public account. Access to Environmental Justice emphasizes the important connections between these underlying concepts and enables us to see how, in practice, they will be operationalized (or not) through the same aspects of legislative design discussed in more detail below. Moreover, Access to Environmental Justice raises critical questions about EIA implementation: are equity-seeking groups accessing EIA? If so, what perspectives, claims, and knowledge do they bring? How are these received in the EIA process, and do they register for the ultimate outcome? Who is not accessing EIA, and what are the barriers? To seed the field for a more detailed analysis of these questions, we begin with two foundational assessments: who is accessing environmental laws and how they are seeking to be heard through these newly reformed legal frameworks.

3. Materials, methods, and definitions

3.1. Materials

Our research consists of a detailed document review of the legislation, regulations, judicial decisions, online environmental assessment registries, and financial disclosure data. Legal materials, such as Canada and BC's new EIA statutes, associated regulations, and relevant court decisions, were accessed using CanLII (https://www.canlii.org/en/), a not-for-profit organization whose mandate is free access to up-to-date legislation and judicial decisions. We obtained project proposal-specific EIA information from the government EIA online registries, which are required by their respective statutes (BC Environmental Assessment Office n.d.; Impact Assessment Agency of Canada n.d.). For each EIA, these online registries contain documents submitted by proponents, Indigenous governing bodies (IGBs), individuals, organizations, and other governments. Finally, we also looked at financial data relating to disbursements made by the Environmental Assessment Office of BC (EAO) and Impact Assessment Agency (IAAC). This funding was provided to IGBs, organizations, and individuals through each jurisdiction's respective participant funding regime. Federal disbursements were found using the Federal Government's proactive financial disclosures website (Canada n.d.). We obtained BC funding data through direct contact with the EAO.5

5

While BC funding is also available to Community Advisory Councils to cover reasonable and necessary travel and out-of-pocket expenses, the Act contemplates that participant funding shall generally go to Indigenous Nations only, and this was reflected in the financial data we received from BC (EAA ss 22(2), 48).

3.2. Scope

Our dataset includes proposals subject to one or both of BC's and Canada's new EIA legislation. We focused our study on project-based assessment only, which remains the predominant form of EIA in Canadian law and practice. Regional assessment and strategic assessment raise equally important questions of Access to Environmental Justice—at the regional and policy scales—and are worthy of their own studies. We also excluded proposals on federal lands, which are assessed through a separate process under the IAA. All project-based EIAs that started under or transitioned to either the EAA or IAA from their enactment up to 1 February 2023, the cut-off date for our analysis of engagement data, are included in this dataset.6 The financial data similarly pertain only to projects assessed under the new EAA and IAA, but this dataset ends on 27 October 2022, as we were limited to the data supplied by the provincial agency. Where a proposal triggered both the IAA and EAA processes collectively, we analyzed engagement and financial disbursements for both assessments. Finally, given our focus on Access to Environmental Justice, we did not consider engagements by or between the proponent and the relevant EIA agency, except to the extent necessary to understand developments in the EIA process. We take it as a given that EIA in BC and Canada is a proponent-driven process, which provides the proponent with a high degree of access to EIA agencies (Westwood et al. 2019).

6

Our dataset is open access: doi:10.5683/SP3/SRIIBK. Note that for projects that were transitioned under the new legislation, our data only captures engagement on those projects that took place under the new legislation and not prior to the transition.

3.3. Methods

We analyzed and described who is accessing EIA and how they are doing so, as follows. First, to identify and analyze who is accessing EIA, we relied on the texts forming the basis of our literature review above, in particular Noble's suggestion that “[o]ne way to approach identification of publics within EIA is to consider the “influence” of a group versus their “stake in the outcome””, to draw different categories of actors within EIA (Noble 2015, 222). Alongside these dimensions of “influence” and “stake”, we also considered markers relevant to accessing environmental justice, namely, representation, recognition, and capacity. From this, we drew the following categories for who is seeking access to EIA (Table 1). We then applied these concepts to the different groups appearing as authors of comments and documents in materials found through the EIA registries and within the financial data we obtained. Where necessary, we obtained additional information about the authors through simple Google searches to seek, for example, organization and group websites that explained their missions and organizational structures.

Table 1.

a. Individuals: Persons interested in contributing to the EIA. Included in this category were all anonymous comments/documents, and those in which a personal name was used. Where names were given, we included individuals who either (a) did not identify themselves as intervening on behalf of or part of any other groups; or (b) despite appearing affiliated with an organized group, identified that their participation was on their own behalf. b. Community groups: Collectives of local individuals, generally sharing similar stakes in the outcome, but who, through collectivization, seek to exert greater influence. Community groups include self-described local users or recreational users of an area affected by the proposal, who have collectivized to either (a) intervene in the EIA and project or (b) engage in socio-ecological issues that may be affected by the proposal. Examples would include groups such as “Fraser Voices Society”, “My Sea to Sky”, or “Sparwood and District Fish and Wildlife Association”. c. Non-governmental organizations (NGO): Environmental NGOs are “self-governing, private, not-for-profit organizations that are geared to improving the quality of life of disadvantaged people [or the environment]” (Vakil 1997, 2057). Their interests are distinct from those of the above actors, as their involvement is motivated by the extent to which the proposal threatens or affirms the NGO's organizational mandate. In this category, we include all not-for-profit organizations with either environmental or social justice mandates not already captured by our community group definition. Examples include “Ecojustice”, “Wildsight”, or “What the Frack Manitoba”. d. Companies: Companies are all registered for-profit corporations other than the project proponent. Generally speaking, company involvement in EIA is motivated by financial interest (for example, construction contracts for the development of the project sites or general support of a proposed project within the same industry). e. Industry groups: Industry groups are collectives that promote the interests of a particular industry yet are not necessarily incorporated or directly for-profit. Like companies, industry group involvement in EIA is generally financially motivated, yet indirectly through, for example, employment opportunities or other success of the industry with which they are affiliated. Examples include the “Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers” and the “Mining Association of Canada”. f. Indigenous governing bodies (IGBs): IGBs are representative institutions of Indigenous Peoples in Canada (UNDRIP 2007, arts 3, 18). Indigenous Peoples are owed constitutional duties of consultation by settler governments under Canadian constitutional law, distinct from any consultative processes owed to the general public (Haida Nation v. British Columbia 2004; Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada 2005). The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples affirms that interactions between Canadian governments and Indigenous Peoples occur on a nation-to-nation basis (UNDRIP arts 18, 19, 32). While the IAA adopts the language of “Indigenous governing bodies” and identifies IGBs as jurisdictions for certain purposes under the Act (IAA s 2), the EAA arguably signals weaker recognition through the terminology of “participating Indigenous nation” (EAA s 14). When referring to entities that hold themselves out as representing a First Nation, Métis, or Inuit community, we use the term Indigenous governing body. g. Indigenous organizations: This category includes all groups other than IGBs whose identity and/or mandate centers on issues of Indigeneity. This includes, for example, treaty rights advocacy groups, Indigenous women's organizations, and Indigenous industry groups. Indigenous organizations may bring to EIA issues of Indigenous jurisdiction, stewardship, economic development, and the distinctive impacts of the proposal on Indigenous Peoples; however, they do not advance these issues as representative governing bodies. |

Categorizing how EIA was accessed was based on a close read of the new legislation to identify modes of engagement, using legal methods of statutory interpretation (Sullivan 2003) and supporting scholarship (e.g., Doelle and Sinclair 2019; Gibson 2020). Through statutory interpretation, we can see that reforms to the IAA and EAA have expanded, deepened, and reinforced possible opportunities for affected individuals and communities to understand and access the EIA beyond the basic form of written comment (Table 2).

Table 2.

a. Request for designation: A request to the agency to conduct an EIA for a proposal that otherwise would not require one. Any person can make this request under both provincial and federal legislation (see EAA s 12; IAA s 9) b. Written comment: A standard form of participation in EIA (Noble 2015, 224–25). Entering specific stages of the EIA requires the agency to provide notice of developments in the EIA process and to enable comments and input from the public. Generally speaking, the opportunity to comment is provided at the early engagement or planning stage, the assessment stage, and the ultimate decision stage. The format is open-ended and facilitated through the online registry: anyone can comment on the EIA and supply whatever perspectives, concerns, evidence, or other input they wish. c. Individual template: A specific kind of comment based wholly or substantially on a standardized template comment drafted by a lead individual or organization. We treated this as a separate mode of engagement because the numbers of template comments, when they exist, typically dwarf other modes of engagement, and they raise distinct questions about collective action and agency influence. d. Community Advisory Committee (BC only): A committee that must be established by the EAO where they consider there is “sufficient community interest in the project”. The role of the committee is “to advise the [EAO] on the potential effects of the applicable project… on the community” (EAA s 22(1)). The EAO's guidelines describes committee members as a collective of representative community members. e. Participant funding: Funding made available to certain parties to enable their participation in the EIA. The IAA participant funding program is open to the public and Indigenous Peoples (IAA s 75), whereas the EAA funding program is available to participating Indigenous Nations only to defray their costs of participating in the assessment (EAA s 48(1)). Participant funding enhances the capacity of interested actors to access EIA and to engage more substantially with the process. f. Judicial review: A court process in which a judge assesses whether an EIA decision by the agency or government was made lawfully. A court challenge can be brought by someone directly affected by the decision (for example, Indigenous Peoples on whose traditional territories the project is proposed) or someone acting in the public interest. The court's role in judicial review is to determine whether the decision complied with the law, not whether the decision ultimately made was a good one. In relation to Indigenous Peoples only: g. Agreements: An agreement entered into with an IGB that determines how the EIA is conducted, by whom, and what procedures will be followed. The agreement may relate, for example, to the conduct of a Review Panel, or the exercise of a ministerial decision whether to approve the proposed project (IAA ss 39(1), 114(1)(c); EAA ss 7(b), 41; and DRIPA ss 6-7). h. Substitution: An agreement that replaces a federal or provincial EIA process with the assessment procedure of an IGB (IAA s 31; EAA ss 41, 24(3)(a)(iii)). |

Expanded opportunities come in the form of early involvement. One of these opportunities is the “request for designation”, the ability of any person to lodge a request with the agency to conduct an EIA on a proposed project that would not otherwise be required under the legislation (EAA s 11; IAA s 9).7 Requests for designation allow those affected to have a direct say in initiating an assessment, indicating to the government which proposals are of particular interest or concern. Similarly, both statutes contain “early engagement” or “planning” stages of the assessment process (EAA pt 4; IAA ss 10–15). The aim of these early stages is for those affected to have a say in the assessment process itself, for instance, by flagging issues of particular concern to be addressed in the assessment.

Deeper engagement is made possible by legislative reforms that create opportunities beyond the standard model of written comments submitted to the agency. In BC, this includes Community Advisory Committees, which are a formal mechanism for supplying local knowledge to the agency. A Community Advisory Committee must be established where there is sufficient community interest in a proposal (EAA s 22). In addition, both the EAA and IAA retain the option of assessment by panels, formalized hearing processes that typically grant interested parties official status to make submissions and pose questions (EAA s 24(3)(a)(ii); IAA s 44). Importantly, both the IAA and EAA recognize new and deeper modes of engagement with Indigenous Peoples. The EAA requires the agency to undergo “consensus-seeking” with participating Indigenous Nations at key process and decision-making points for the EIA (e.g., EAA ss 16(3) 19(1); 29(3)). Moreover, the Act allows for agreements to be entered into with Indigenous Nations to recognize Indigenous-led or joint EIA (EAA s 41(2)–(3)). The IAA includes IGBs as jurisdictions (IAA s 2). This means that Canada can decide to rely on assessments led by IGBs in the same fashion they often rely on assessments conducted by provincial authorities (IAA s 31, Wright 2020, 196–97).

Furthermore, both statutes contain enhanced mechanisms for decision-makers to demonstrate that they have heard, considered, and addressed the concerns and issues raised by those who access EIA. The EIA must consider comments received as part of the assessment (EAA s 28(2)(c)-29(1); IAA s 22(1)(n)). Both statutes require the assessment to address the disproportionate impacts of a proposed project depending on gender, racial, and other identity markers (EAA s 25(2)(d); IAA s 22(1)(s)). The IAA now includes a requirement that the ultimate decision contain detailed, public reasons (IAA s 65(2)). The EAA includes specific reason-giving obligations that address the consent or lack of consent of participating Indigenous Nations (EAA ss 17(6), 29(2), 29(7)). In BC, where a request for designation is rejected, the relevant minister must provide reasons for their decision (EAA s 11(9)). Under the IAA, reasons for rejecting a request for designation are not mandatory (IAA s 9(4)); however, the minister's practice has been to offer reasons for requests for designation decisions.

Finally, both BC and Canada offer funding support to enable certain groups to access EIA. The IAA retains a long-standing statutory obligation to provide participant funding (IAA s 75) and the EAA now specifically authorizes a tariff program to provide funding to participating Indigenous Nations (EAA s 48).

These modes for accessing EIA are summarized in Table 2.

Finally, with respect to categorizing the types of proposals undergoing EIA, we have largely relied on the categories supplied by the agencies. Because these categories differ slightly across the two jurisdictions, we combined them into seven categories of assessment across BC and Canada's EIAs. Our resulting proposal types were Transport Infrastructure (e.g., highways); Marine and Freshwater Infrastructure (e.g., port expansion); Other Infrastructure (e.g., waste management); Mining; Oil and Gas; and Nuclear Projects.8

7

The Supreme Court of Canada ruled on the constitutionality of the federal Impact Assessment Act while this article was in production: Reference re Impact Assessment Act, 2023 SCC 23. The federal government has committed to making changes to bring the Act in line with the Court's ruling. These changes will likely affect the types of projects subject to a federal EIA, but are not likely to affect most of the modes for accessing environmental justice as described in this paper. As the federal government is considering changes to the Act, it has paused the requests for designation mechanism: “Government of Canada Releases Interim Guidance on the Impact Assessment Act" (26 Oct 2023), online: https://www.canada.ca/en/impact-assessment-agency/news/2023/10/government-of-canada-releases-interim-guidance-on-the-impact-assessment-act.html.

8

Five projects were also recategorized according to our proposal types, where the agency's categorization seemed inappropriate when compared to the activity being undertaken and why. These were the Webequie Supply Road Project and Marten Falls Community Access Road Project (both changed from "Highways and Roads" to "Mining"); the Long Pond Development Project (changed from "Building and Property Management" to "Marine and Freshwater Infrastructure"); the Hydrogen Ready Power Plant Project (changed from "Other, not otherwise specified" to "Oil and Gas’’); and the provincial assessment of the GCT Deltaport Assessment (changed from "Transportation" to "Marine and freshwater infrastructure").

4. Results and discussion

Table 3 provides an overview of who is accessing EIA and through which modes of engagement. At this high level, we see that the provision of written comments remains the dominant mode for engagement, despite the availability of different opportunities for engagement (see Section 4.4). Individuals and IGBs submit written contributions in higher numbers than other interested and affected parties.

Table 3.

| Request for designation | Written comments* | Agreement | Substitution with Indigenous nations | Court challenge | % Federal funding | % BC funding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals | 13 | 2851 | 0 | 2.83% | |||

| Community groups | 26 | 123 | 0 | 3.13% | |||

| NGOs | 45 | 170 | 0 | 6.61% | |||

| Companies | 4 | 47 | 0 | 0.07% | |||

| Industry groups | 0 | 33 | 0 | 0.49% | |||

| Indigenous organizations | 4 | 23 | 0 | 8.20% | |||

| Indigenous governing bodies | 37 | 558 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 78.67% | 100 |

*

Written comment is a broad category for all comments, documents, and other contributions made to the agency by the categories of actors listed in Table 1. It does not include template comments, which are discussed separately in the text below. Note also that Community Advisory Committees are discussed separately in the text.

To refine our analysis, we divided proposals temporally to account for variation in how far proposals have progressed through the EIA process and thus the greater opportunities for engagement that result from this progression.

We term pre-assessment proposals as all those that have not proceeded to the assessment stage, either because a request for designation was denied, the proposal was terminated, or because the assessment stage had not started at the time of our analysis. Across both jurisdictions, 38 proposals fell within our pre-assessment category.

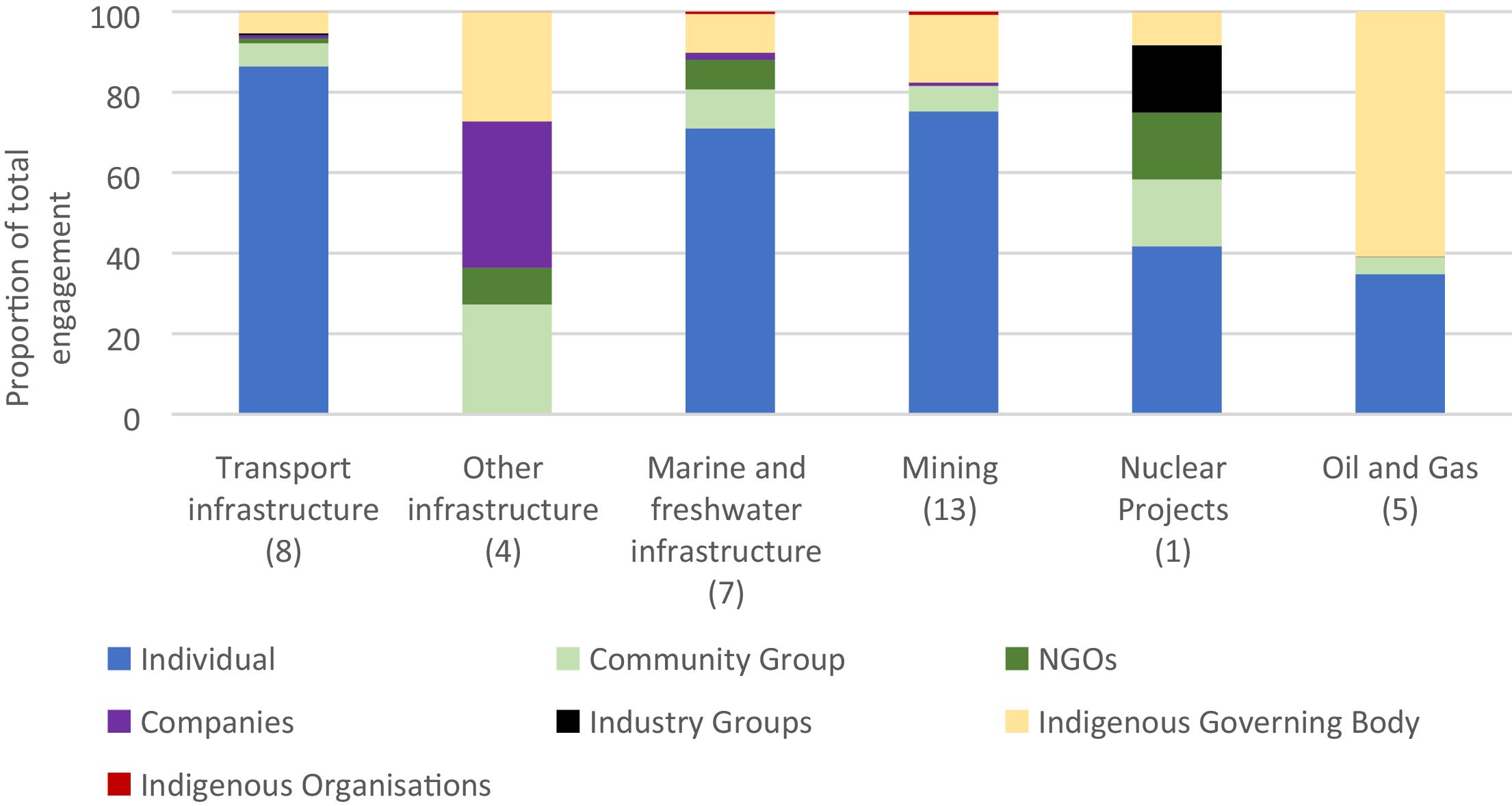

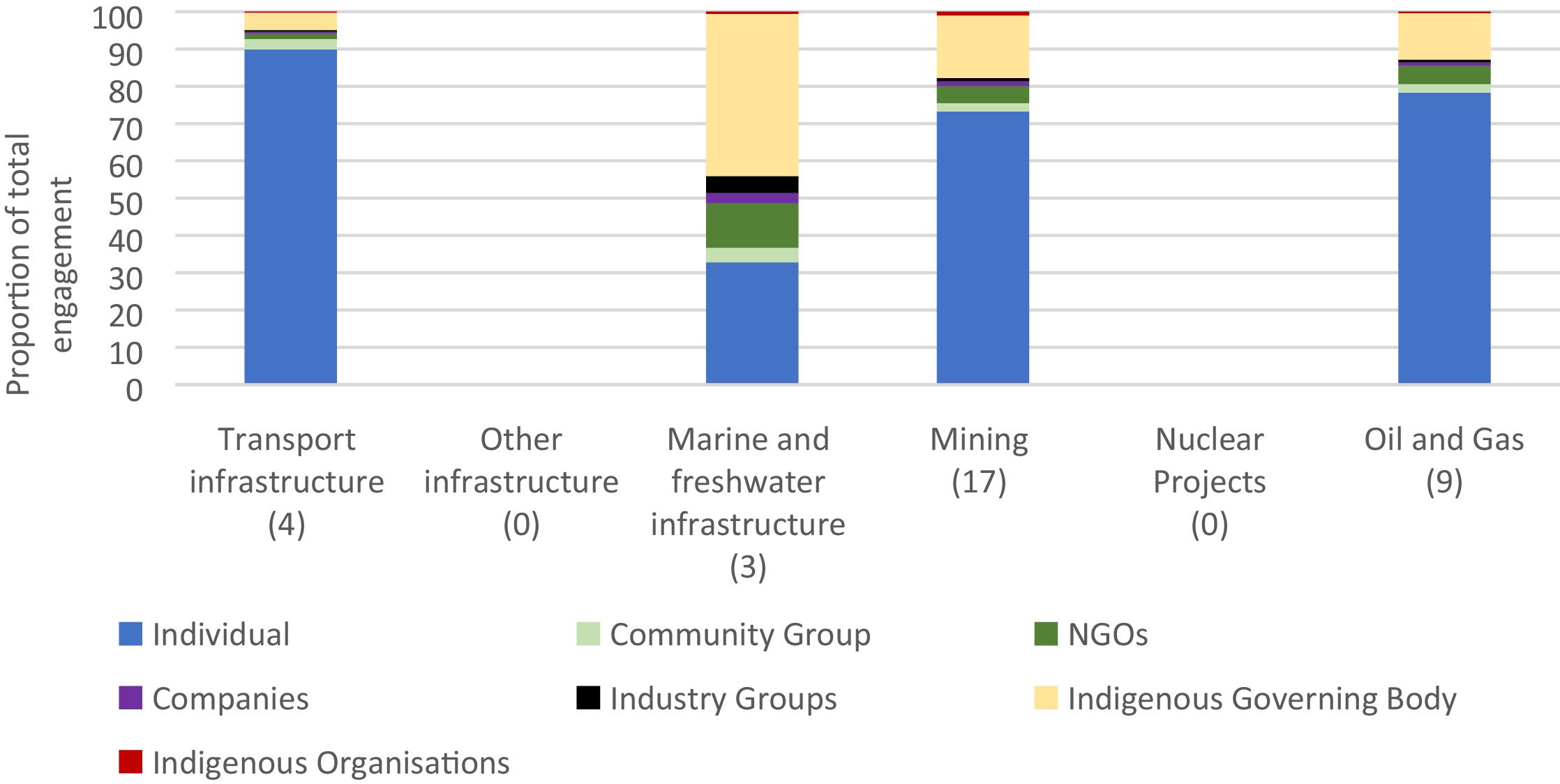

At the time of analysis, 33 proposals had proceeded through to assessment, in which we include early engagement and planning stages as well as those undergoing the actual assessment. No final reports on EIAs had yet been issued and no EIA decisions had been made. Figures 1 and 2 present our engagement data—that is, the total instances of engagement across all modes outlined in Table 2. We show the average proportion of engagements, by actor, for each proposal type. The number of individual proposals within each type is in parentheses along the x-axis.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

We highlight four themes that arise from our initial assessment of EIA data under the IAA and EAA and identify a range of questions for future research.

4.1. Geography plays a role in determining who accesses EIA and when

Comparing pre-assessment with assessment proposals, the data show shifting proportions of who is accessing EIA based on proposal type. Pre-assessment proposals see relatively high proportions of engagement by individuals for transportation proposals and marine and freshwater infrastructure (Fig. 1). This contrasts with higher levels of engagement by IGBs for oil and gas proposals. One possible explanation of these differences is that geographic proximity to a proposed project plays a role in pre-assessment engagement in the EIA regime.

Transportation and water-based infrastructure tend to be in or near urban centres with high population numbers. For these two categories of proposals, we see very high proportions of engagement by individuals, exceeding 70% of the total proportion of engagements at the pre-assessment stage. The location of proposals in or near urban centres means that more individuals are likely to be aware of these proposed developments, enabling their access to EIA at this very early stage. For example, the Bradford Bypass, Ontario Line, and Waterloo Airport Runway proposals are located in Toronto or Waterloo, both major urban centres, and have attracted high levels of engagement from individuals.

In contrast, oil and gas development often occurs in remote and rural locations, where fewer individuals may be immediately aware of and ready to respond to such proposals at the pre-assessment stage. At the same time, oil and gas proposals often have profound impacts on Indigenous jurisdiction, Aboriginal and treaty rights, and the economic development of remote and rural Indigenous communities. Canadian governments hold constitutional duties to consult and accommodate Indigenous Peoples where an activity affecting rights or titles is proposed; thus, Indigenous Peoples potentially affected by a project likely receive formal governmental notices of proposals regardless of specific EIA requirements. Proponents also often proactively reach out to IGBs, seeking to secure community support and negotiate impact benefit agreements (IBAs) (Papillon and Rodon 2017; Scott 2020). The incentives for early notification and the stakes of the projects for Indigenous Peoples could explain the high proportion of engagements for oil and gas projects by IGBs in the pre-assessment phase. Further study is needed to better understand how interactions between geography, jurisdiction, and arrangements such as IBAs affect engagement across time and project types.

Mining, however, seems to depart from this explanation, with a high proportion of individual engagement at the pre-assessment stage. In fact, this is due to relatively high individual engagement with one proposal—the Bamberton Projects—under the EAA. The Bamberton Projects proposal is for a mining expansion on Vancouver Island. Thus, the high proportion of individual engagement can be explained by its location in the well-populated eastern swath of Vancouver Island and the fact that the mine already exists and has been an ongoing source of local concern.

The proportions of engagement then shift between pre-assessment and assessment proposals. Engagement by individuals dominates engagement for oil and gas for proposals at the assessment stage, with a lower proportion for IGBs (Fig. 2).

We also see that proposals located in or near urban centers or that involve a project spanning a long distance (for example, a highway or oil pipeline) have higher levels of engagement and participant funding. Of the eight proposals with the highest levels of engagement at the assessment stage, half are located in or near urban centers. In addition, a majority of federal (51.32%) and BC (62.91%) participant funding has been allocated to proposals with one or both of these geographic features. Given these shifting proportions of engagement, an Access to Environmental Justice perspective suggests a closer examination of these proposals is needed to assess whose perspectives and knowledge are ultimately reflected in the assessment process and the ultimate decision.

4.2. Oil and gas projects dwarf other proposal types

Oil and gas proposals attract the most participant funding and an overall high level of engagement. In particular, the Gazoduq Project, a proposed 780 km natural gas pipeline that would transect northern Ontario and Quebec, has received nearly one-third of all federal participant funding (32.71%). This goes hand-in-hand with high engagement: 17.82% of all engagement across both BC and federal processes is focused on Gazoduq. Under the BC EAA, Tilbury LNG Phase 2 Expansion, another oil and gas project, has received the most funding and engagement. Over one-third of BC disbursements are attributed to the Tilbury proposal (34.55%). Tilbury received 8.28% of all engagements when calculated across both the BC and federal regimes. Table 4 shows the dominance of oil and gas in relation to participant funding and engagement relative to other project types.

Table 4.

| Oil and gas | Transport infrastructure | Other infrastructure | Marine and freshwater infrastructure | Mining | Nuclear projects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant funding | ||||||

| IAA | $3 755 236 (50.02%) | $1 570 934 (20.93%) | N/A | $619 990 (8.26%) | $1 561 182 (20.80%) | N/A |

| EAA | $501 000 (43.72%) | N/A | N/A | $325 000 (28.36%) | $320 000 (27.92%) | N/A |

| Engagement proportions (excluding template comments) | ||||||

| IAA and EAA | 32.15% | 17.51% | 0.29% | 9.28% | 40.48% | 0.32% |

Table 5.

| Total RFDs | Approved | Denied | Decision pending | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAA | 30 | 4 (13.3%) | 25 (83.3%) | 1 (3.3%) |

| EAA | 8 | 1 (12.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 2 (25%) |

Finally, oil and gas proposals have attracted significant engagement through template campaigns. Template campaigns are started by a lead commenter (often an NGO) who encourages individuals to submit comments based on their template, often resulting in hundreds or thousands of the same or similar comments being delivered to the agency (Table A2). A total of ten proposals in our dataset were the subject of template comment campaigns. While only three of these proposals were oil and gas proposals, they generated approximately half of the template comments submitted across all ten of these proposals for a total of 6425 individual template comments (49.3% of all template comments).

The prevalence and controversy surrounding oil and gas and mining in Canada are well documented, and so high levels of engagement may be anticipated (Hoberg 2018). Given the long-term environmental impacts of these projects, this amount of engagement and allocation of funding resources may well be warranted from an Access to Environmental Justice perspective. Further study is needed to determine the influence that such high engagement, including template campaigns, has on ultimate decision-making. However, it is also worth considering that there may be an opportunity cost associated with one proposal type dwarfing the engagement and funding opportunities of others. Presumably, the total pool of participant funding available for proposals is not infinite, nor is the capacity of EIA agencies to respond to large levels of engagement. The allocation of significant funding and resources to oil and gas proposals may therefore mean less is available to support engagement on other types of proposals.

4.3. Requests for designation are an important site for accessing environmental justice

Requests for designation (RFD) allow anyone to make a request to the relevant provincial or federal minister to consider conducting an EIA for a proposed project that does not otherwise require one under the relevant legislation (Table 2). Prior to the 2018/2019 legislative reforms, only BC had this mechanism, yet it was infrequently used and was virtually never successful. In the five years preceding the 2018 EAA reforms, only eight requests for designation were made, and only one was approved by the minister. This singularly approved request was made by the proponent, indicating that RFDs were not a mechanism for affected individuals, communities, and groups to access environmental justice. The RFD mechanism is new to federal EIA law.

Within our dataset, a total of 38 proposals have been the subject of RFDs: 30 under the IAA and 8 under the EAA. Across federal and BC assessments, 104 different organizations, Indigenous groups, and individuals have made requests to designate these projects as reviewable. NGOs, in particular, have been active in this space by initiating or participating 45 times in RFDs. This preliminary evaluation suggests that RFDs have become an important site for interested and affected parties to make their concerns about potential impacts known to EIA agencies. Of the 38 proposals subject to RFDs, five have been approved (see Table 5). While amounting to only a 13% success rate, it nonetheless shows that, post-law reform, RFDs are the live site of decision-making about EIA. At the federal level, RFDs are not being rejected pro forma. In fact, the federal minister and agency have adopted analysis and reasoning practices that go beyond what is strictly required by the IAA. For each RFD, the agency analyzes the concerns expressed, the potential impacts, and any existing mechanisms—outside of EIA—for addressing those issues. This analysis is provided to the minister and published with the minister's reasons for the decision. At the very least, the introduction of the RFD mechanism in the IAA has enabled interested and affected parties to provoke some measure of transparent action on the part of the agency and minister.

This transparency also enables preliminary analysis of the features that may be relevant to RFD success (see Appendix A, Table A1). First, high levels of engagement in the RFD process seem to influence the success of the RFD. Four of the five accepted RFDs had the highest numbers of requests made and the highest number of individual comments on these requests.9 Three of these accepted RFDs were also subjects of template comment campaigns. In each instance, the minister cited the concerns expressed by requesters and commenters as a rationale for granting the RFD. At the same time, it is worth noting that public concern and template campaigns may not be sufficient; the Bradford Bypass Project, which received one of the highest numbers of template comments, was ultimately not designated.

For four of the five accepted RFDs, IGBs were involved in making the requests. While this might suggest that RFDs are a site of recognition of Indigenous perspectives, concerns, and even jurisdiction, the fact that a requester was an IGB was not cited as a reason for granting any of these requests. Rather, in each case, the minister referred to potential social and ecological impacts on Indigenous Peoples and impacts on Aboriginal rights and titles. Notably, for 15 of the 17 denied RFDs in which the request was made by at least one IGB, the reasons for the denial included the statement that the minister was satisfied that impacts on Indigenous Peoples rights and titles could be addressed through other legal requirements and regulatory frameworks.

Finally, the minister's reasons for approving RFDs demonstrate specific concerns about proposal impacts. In particular, there is a consistent concern for impacts on endangered species and fish and fish habitat (issues that fall squarely within federal jurisdiction) as well as transboundary impacts that cannot be fully addressed by any one province. In addition, two RFDs were approved, in part because the proposed project was very near the threshold for automatic designation under the IAA.

While further analysis is needed, early implementation of RFDs under the IAA suggests that it is an additional mechanism for affected individuals and communities to be heard in the EIA. However, the mere availability of additional modes of engagement does not itself lead to greater Access to Environmental Justice outcomes with the ultimate EIA decision. In fact, early decision-making suggests that the federal agency and minister are principally attending to environmental impacts and jurisdictional issues rather than the broader suite of interlocking social, environmental, and economic concerns at the centre of Access to Environmental Justice.

9

Eskay Creek Revitalization Project (BC EAA) is the outlier in terms of engagement. Eskay Creek is the solely approved RFD under the EAA and is somewhat unique. The RFD approval was supported by the proponent and seems to have been initiated in order to access the consent-agreement provisions of the EAA, discussed in Section 4.4. This suggests that RFDs under the EAA may be a continuation of the pre-reform practice of responding principally to proponent preferences.

4.4. Some modes of access are opaque and untested

As described above, the EAA and IAA bring the promise of deeper and more meaningful engagement in the EIA. Community Advisory Committees and panel reviews, in principle, offer opportunities for more intensive involvement in the EIA by those interested and affected. Moreover, consent agreements and Indigenous-led assessments are mechanisms for Canadian EIA regimes to recognize and implement Indigenous environmental and stewardship laws. It is not yet clear whether any of these mechanisms will play a significant role in deepening engagement in EIA. Nor is it yet clear whether the courts will be an important site for those affected to access environmental justice.

Community Advisory Committees (CAC), a mechanism to facilitate the input of local knowledge under the BC EAA, had, at the time of analysis, been constituted for three of ten proposals undergoing a BC EIA. While it is encouraging from an Access to Environmental Justice perspective to know that these committees exist, their role, operation, and composition seem highly variable in practice. The EAO describes a flexible approach to CACs, noting that “[t]he format and structure of a CAC will depend on the potential effects of a project and community interest in a project, amongst other considerations” (Environmental Assessment Office BC 2020, 4). What this entails is far from clear. Some proposals display meeting minutes from CAC meetings in the public registry; others do not. Indeed, it is unclear whether CACs always provide a means for discussion and formalized input under the EIA, or simply enhanced notice for interested persons. The online registry invites commenters to “subscribe” to a CAC service to receive updates about the EIA at proposal milestones, which suggests the latter will generally be the case. The EAO notes that additional engagement opportunities may be available at its discretion, but without transparency on the reasoning process undertaken in exercising this discretion (Environmental Assessment Office BC 2020, 6). Since the public already has the ability to comment on project proposals under the EAA, it is unclear whether and how CACs provide a richer opportunity for community-government engagement.

The opacity of CACs raises other issues of Access to Environmental Justice. It is not clear whether interested persons and affected communities are aware that CACs are a possibility. CACs were described in the law reform process as “increasing the trust of less technically prepared participants” (Fraser and Hwitsum 2018, 26). However, the option to “subscribe” to updates for a proposal—the source of most CAC membership—is available online through an inconspicuous link for each proposal (Fig. 3). It is unclear whether the EAO is providing for an avenue of CAC participation beyond this. Even those who are aware of CACs may not see the value in participating, given the lack of clarity in their operation and potential for impact.

Fig. 3.

Panel reviews are a long-standing format for EIA in Canada (Doelle 2008, 154, 177–81). They tend to have a more formal hearing structure, allowing for intervener status and more intensive modes of participation, such as cross-examining proponent evidence. Since the reforms to the IAA and EAA, only two proposals have been assigned to panel reviews, both under the IAA. When collecting our data, neither panel review had terms of reference. It is thus too early in the process to yet know whether the processes for these panel reviews will create modes of engagement that differ from the written notice-and-comment mechanisms that characterize the standard EIA. A positive reform under the IAA was the removal of the restrictive gatekeeping requirement of standing for intervenors. However, it remains to be seen whether this will have a noticeable effect on the opportunity for concerned parties to access panel reviews.

Similarly, it is too early to know whether legislative changes to recognize Indigenous jurisdiction will have tangible outcomes on a wide scale. The Tahltan Nation and BC have entered into the first consent agreement, which makes Tahltan consent required for the proposed Eskay Creek Revitalization to proceed (Tahltan Central Government and British Columbia 2022, ss 4.3, 4.7, 4.9). It also provides that the proposal will be subject to an additional Tahltan Risk Assessment, with Tahltan's assessment and sustainability criteria. The Tahltan consent agreement shows the potential for shared decision-making in BC EIA law. We have yet to see any instances of the federal agency substituting an Indigenous EIA for its own, nor have we seen regulations or agreements that would enable this substitution. This remains a space to watch for future developments as Indigenous Peoples across the country continue to revitalize their stewardship laws and build capacity for greater roles in EIA (First Nations Energy and Mining Council 2022; Nishima-Miller and Hanna 2022; Sankey et al. 2023, 32–33).

As expected, based on the timing of our analysis, there has been little involvement of the courts in the interpretation and enforcement of the new legislation. Only three judicial reviews have been brought, and two were launched by the project proponents (Coalspur Mines (Operations) Ltd. v. Canada 2021; GCT Canada Limited Partnership v. Vancouver Fraser Port Authority 2022). The third was brought by the Ermineskin Cree Nation, which opposed the approval of an RFD (Ermineskin Cree Nation v. Canada 2021). In the Ermineskin Cree Nation case, the Court affirmed the need for the government to fulfill its duty to consult prior to approving the RFD. These court cases raise questions about new requirements for project proponents at the early stages of the process under the IAA. But it remains too soon to say whether the courts will play a significant role in upholding the Access to Environmental Justice affirming features of the IAA and EAA.

The fact that—after four years—the public record does not provide basic clarity on the implementation of new modes of engagement under the IAA and EAA is unsettling from the perspective of Access to Environmental Justice. This lack of clarity, in and of itself, suggests that reforms are falling short of the enhanced Access to Environmental Justice touted during the reform process. Recalling the critical perspective brought by environmental justice scholars, Indigenous groups, and activists, it may be that some of these reforms—in particular CACs and panel reviews—only provide a veneer of change, rather than a pathway to procedurally and substantively just environmental decisions.

4.5. Many questions remain open for further study

Our preliminary evaluation of the early implementation of these legislative reforms invites a range of questions about Access to Environmental Justice that require further study. First, since this is a study of who is accessing EIA, it does not directly answer the question of who is not accessing EIA. Follow-up work with community research partners may be able to elicit insights into issues of capacity and strategy that impact decisions to engage with EIA. Second, detailed qualitative work is needed to assess substantive dimensions of environmental justice: what concerns about disproportionate environmental harms and benefits are being raised in EIA and through what modes of engagement? How are these concerns received by the agencies, and do they influence decision-making? A closer analysis of collective modes of engagement—such as the impact of template comment campaigns and the use of CACs—can help us understand whether environmental justice concerns are being represented through these modes and, if so, their reception by government decision-makers. Third, since not all modes of advancing Access to Environmental Justice fit within the four corners of EIA, the interaction between EIA and IBAs, other forms of contracting, Indigenous proponents, and joint venture arrangements with equity-seeking groups all require further research.

Finer-grained questions also emerge. For instance, is there a trade-off between the number of modes of engagement and how meaningful or impactful this engagement is? While a range of modes may reach different audiences with different capacities, it may also create confusion or participation fatigue amongst affected communities. Relatedly, this trade-off may extend to the agencies and decision-makers attempting to synthesize and reconcile contributions from multiple modes of engagement. In short, more engagement may not generate different outcomes, such as refusing to authorize a proposal or attaching more responsive conditions or mitigation measures to such approval. In addition, future research should also closely analyze participant funding programs. By following the funding, we can better understand how the amount, timing, and conditions of the funding affect the ability of those seeking to access environmental justice to make their concerns heard. Moreover, funding research can assess issues of equity in funding disbursements. For instance, our preliminary analysis of the financial data raised potential questions about large sums of federal participant funding going to a community group seemingly established by the proponent.10 Future research should examine the interactions between agency-led and proponent-led engagement. These interactions raise questions of equity in accessing public funds as well as rule-of-law questions of independence and impartiality. The analysis here provides a framework for future study.

10

Financial data obtained through the Federal Government's proactive disclosure website shows that a total of $105 000 was paid to several individuals in relation to the Wasamac Gold Project. Those individuals are also associated with a "Neighbourhood and Community Task Force" seemingly established by proponents of the Wasamac Gold Mine Project.

5. Conclusion

Contemporaneous reforms to Canada and British Columbia's EIA laws present an opportunity to connect a number of important policy and legal concepts that help us better understand the interlocking objectives of EIA. In this paper, we have described how concepts of environmental justice, public participation, the rule of law, and access to justice intersect to form the overarching aim of Access to Environmental Justice. By this, we mean the ability of individuals and communities who are disproportionately impacted by environmental harms to access legal and regulatory processes and to have their concerns about environmental risks and benefits heard and addressed through environmental decision-making and dispute resolution. As a decision-making framework with explicit aims of providing meaningful opportunities for participation, recognizing distinctive Indigenous rights and interests, and offering reasoned decision-making that accounts for a diversity of perspectives, EIA should be understood as a key opportunity to advance Access to Environmental Justice in Canadian environmental law.

This paper has presented a preliminary analysis of whether recent reforms to the EAA and IAA have facilitated Access to Environmental Justice. It asks foundational questions about who is accessing EIA post-reforms and how they are seeking to be heard. Our initial analysis revealed a number of potential themes and influences on Access to Environmental Justice through EIA, each of which seeds the field for further study. We found that geography and proposal type both influence who is accessing EIA: pre-assessment, project proposals near urban centres tend to attract high proportions of individual engagement, whereas IGBs are more prevalent in engagement with more rurally situated oil and gas proposals. Once proposals proceed to assessment, these proportions shift. We found that oil and gas proposals dominate both engagement and disbursement of participant funding, likely reflective of the controversial status of oil and gas development in Canada and BC. We also found that new modes of engagement may be important sites for Access to Environmental Justice though whether these lead to more just outcomes on the ground remains to be seen. In particular, we found that requests for designation have been one way for concerned and potentially affected individuals, groups, and nations to be heard and responded to in EIA. And we highlight how a lack of transparency and experience impedes our understanding of whether other new modes of engagement will advance Access to Environmental Justice, such as panel reviews, CACs, and agreements with IGBs.

This study raises a range of questions about the implementation of newly reformed EIA laws. Anchoring future research in the framework of Access to Environmental Justice promises to elicit new insights about how EIA law is performing in Canada and beyond.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Gabrielle Edwards for assistance with data entry, and Kevin Hanna, Lauren Arnold, Jeffrey Nishima-Miller, and Matthew Mitchell for their helpful comments on early drafts. Thanks to the generous feedback of the three anonymous peer reviewers, whose comments all greatly improved the article. Finally, thanks to Martin Olszynski and David Wright for last-minute clarifications on some technical aspects of the IAA. Any errors are our own.

References

Agyeman J., Cole P., Haluza-DeLay R., O'Riley P. 2010. Speaking for ourselves, speaking together: environmental justice in Canada. In Speaking for ourselves: environmental justice in Canada. Edited by Agyeman J., Cole P., Haluza-DeLay R., O'Riley P. UBC Press. pp. 1–26.

André P., Enserink B., Conner D., Croal P. 2006. Public participation international best practice principles. Special Publication Series No. 4. International Association for Impact Assessment, USA.

Armitage D.R. Collaborative environmental assessment in the Northwest Territories, Canada. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 25: 239–258.

Arnstein S.R. 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4): 216–224.

Ball M.A., Noble B.F., Dubé M.G. 2013. Valued ecosystem components for watershed cumulative effects: an analysis of environmental impact assessments in the South Saskatchewan River Watershed, Canada. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 9(3): 469–479.

BC Environmental Assessment Office. n.d. Environmental assessments. Government Website. E-Project Information Centre. Available from https://projects.eao.gov.bc.ca/ [accessed 23 April 2023].

Beierle T.C., Cayford J. 2002. Democracy in practice: public participation in environmental decisions. Resources for the Future. Washington, DC.

Bingham T.H. 2011. The rule of law. Penguin, London.

Booth A., Skelton N.W. 2011. ‘We are fighting for OURSELVES—first Nations' Evaluation of British Columbia and Canadian environmental assessment processes. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management, 13(3): 367–404.

Borrows J. 2010. Canada's Indigenous constitution. University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

British Columbia. 2018. Environmental assessment revitalization discussion paper. Discussion Paper. BC Environmental Assessment Office, British Columbia. Available from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/natural-resource-stewardship/environmental-assessments/environmental-assessment-revitalization/documents/ea_revitalization_discussion_paper_final.pdf.

British Columbia. n.d. Environmental assessment revitalization—Province of British Columbia. Government Website. Environmental Assessment Revitalization. Province of British Columbia. Available from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/natural-resource-stewardship/environmental-assessments/environmental-assessment-revitalization.

Bullard R.D., Johnson G.S. 2000. Environmental justice: grassroots activism and its impact on public policy decision making. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3): 555–578.

Canada. 2017a. Building common ground: a new vision for Impact Assessment in Canada. Final Report. Expert Panel for the Review of Environmental Assessment Processes, Ottawa. Available from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/themes/environment/conservation/environmental-reviews/building-common-ground/building-common-ground.pdf.

Canada. 2017b. Environmental and regulatory reviews: Discussion Paper. Assessments. 29 June 2017. Available from https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/conservation/assessments/environmental-reviews/share-your-views/proposed-approach/discussion-paper.html.

Canada. n.d. Proactive disclosure. Government Website. Proactive Disclosure. Accessed 23 April 2023. http://open.canada.ca/en/proactive-disclosure.

Chalifour N.J. 2009. A (pre) cautionary tale about the kearl oil sands decision: the significance of Pembina Institute for Appropriate Development, et al. v. Canada (Attorney-General) for the future of environmental assessment. McGill International Journal of Sustainable Development Law and Policy, 5(2): 251.

Chalifour N.J. 2015. Environmental justice and the charter: do environmental injustices infringe Sections 7 and 15 of the charter? Journal of Environmental Law and Practice, 28(1): 89–124.