A recent literature review of private land conservation studies worldwide identified Canada as one of the most studied countries, following the USA, Australia and South Africa (

Cortés-Capano et al. 2019). However, besides a few notable exceptions (e.g.,

Gerber 2012;

Bunce and Aslam 2016), land trusts have not been studied much in Canada even though they are an increasingly important approach to private land conservation. At the same time, there has been increasing interest in trying to understand how land trusts could adapt their operations in response to the impacts of climatic change on the distribution of plant and animal communities (e.g.,

Ruddock et al. 2013;

Rissman et al. 2015;

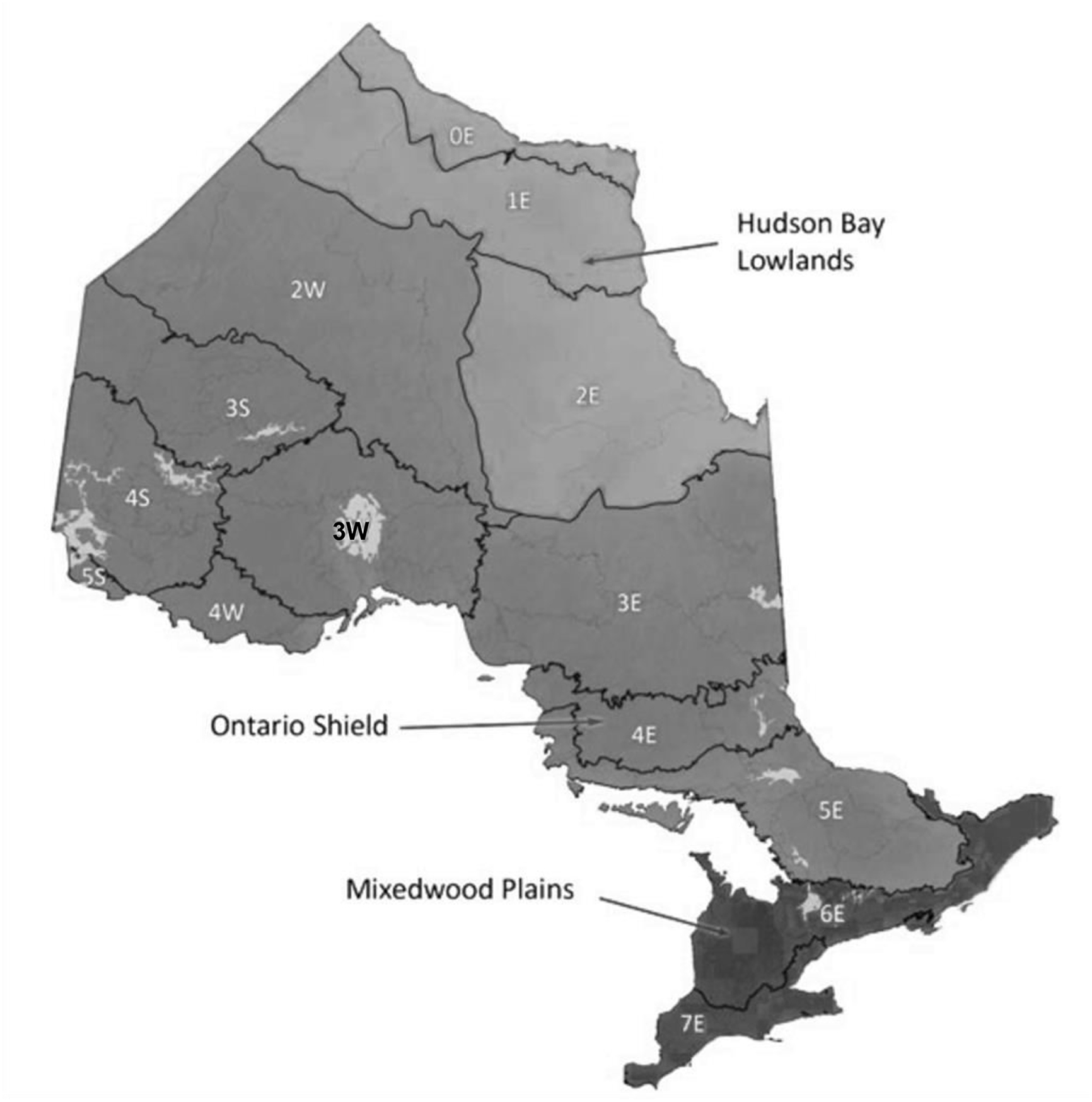

Owley et al. 2018). Our work is addressing this combined need for increased knowledge on Canadian land trusts and on land trust climate change adaptation. Focusing on land trusts in Ontario, Canada, the experiences gathered through our knowledge translation process demonstrated a number of challenge and facilitator themes for the uptake and application of climate change knowledge.

6.1. Challenges and facilitators

Our results mirror the findings of other studies in the conservation decision-making space. Regularly encountered factors that influence the use of evidence in decision-making include the accessibility of evidence; the relevance and applicability of evidence; the capacity, resources, and finances of a participating organization; and transaction costs for learning the evidence (

Kadykalo et al. 2021;

Cooke et al. 2023). Many land trusts that participated in our knowledge translation activities reported funding constraints as a challenge to pursuing climate change work at their organization. Environmental non-governmental organizations (NGOs), such as land trusts, are often facing funding challenges that affect their ability to do mission work or take on additional projects (

Weerawardena et al. 2010;

Beachy 2011;

Lasby and Barr 2018;

Canada Helps 2022). Various studies have demonstrated that many NGOs lack adequate funding, particularly predictable and long-term funding, to sustain operations (

Weerawardena et al. 2010;

Beachy 2011). In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic was a very difficult time for all NGOs, causing losses of revenue, increased costs, and demand for their services outstripping capacity (

Ontario Nonprofit Network 2022). Of all Canadian NGOs, environmental organizations receive a very small proportion of the donations from overall charitable giving in Canada, ranging between 2% and 5% over the last two decades (

Lasby and Barr 2018;

Canada Helps 2022). These funding challenges in turn affect organizational capacity in the form of staff recruitment, retention, and training, staff time allocation, volunteer training and supervision, and access to resources needed to address climate change.

Climate change adaptation and mitigation actions are lacking at global and national scales, despite the known urgency of the crisis. Multiple studies have identified that adaptation is not being undertaken by many groups due to lack of capacity, unclear frameworks, lack of understanding of real or anticipated climate change impacts, and confusion of what needs to be done (

Lemieux and Scott 2011;

Lemieux et al. 2011;

Eisenack et al. 2014;

Baird et al. 2016;

Stafford-Smith et al. 2022;

Barr et al. 2021;

Henstra 2017) . Our experiences suggest that capacity constraints in the land trust community are manifested in several ways. Land trusts reported lack of staff time, volunteer time, technical expertise and knowledge about lands as barriers to acting on climate change. Much like businesses in Canada, the majority of NGOs tend to be small organizations with 60% having less than 10 employees (

Statistics Canada 2007). Unlike small businesses, however, NGOs rely very heavily on volunteers for labour with the average Canadian NGO having a full-time equivalent split of 36% volunteers and 64% employees and contractors (

Statistics Canada 2007).

The story is quite different for environmental NGOs where the split is skewed much heavier towards volunteers (70% volunteers and 30% staff) (

Statistics Canada 2007). Recent reports show the trend continues with 90% of Canadian charities employing ten or fewer full-time staff and 58% being fully run by volunteers (

Canada Helps 2022). NGOs are also facing a human resources crisis for recruitment and retention of staff members, likely due to precarious and lower paying work than other sectors (

Ontario Nonprofit Network 2022).

Paralleling the previously described national-level trends, most Ontario land trusts are small and depend on volunteers for labour. Of the 24 Ontario land trusts for which data was available at the time of the current study, thirteen (54%) had ten or fewer staff members and eight (33%) had no paid staff members at all (M. Johnston-Clayton, personal communication, March 9, 2023). These capacity restrictions often result in staff members who are overworked and unable to take on additional projects or challenges, such as climate change adaptation, or to train and supervise additional volunteers. A mixture of staffed and volunteer land trusts participated in our knowledge translation activities, but the majority (76%) of those who participated in the workshop series were land trusts with salaried staff members, suggesting that adequate human resources is a key component of engaging with climate change adaptation work.

But a lack of climate change adaptation capacity is not limited to the environmental NGO sector in Canada. A recent study by

Barr and Lemieux (2021) indicates that also Canadian national parks seem to lack progress on climate change adaptation despite the growing understanding of a need to do so. The evidence suggests that while national parks may have strengths such as in the mapping of the local ecological resources and access to climate change planning tools, there are challenges such as in the training of staff members and their empowerment to take climate change action (

Barr and Lemieux 2021).

Given that land trusts operate in a range of locations, with differing geographic and demographic pressures and concerns, it is unsurprising that there is also a range of perceptions for how to best prepare for climate change. Adaptive management approaches may be avoided for numerous reasons including difficulty understanding climate science (

Nordgren et al. 2016), resource deficits (

Lonsdale et al. 2017), cognitive dissonance or apathy toward the problem (

Davidson and Kecinski 2022), or a preference for a passive management approach (

Hagerman and Satterfield 2013). The latter is particularly prevalent in more remote land trusts where larger intact habitats are being protected and where the range of acute environmental threats might be relatively lower compared to land trusts located in more densely developed regions.

Despite the reluctance of some land trusts to actively engage in climate change adaptation, most land trusts already make management decisions for their stewarded lands that regularly align with climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies. Decision makers consider environmental, financial, and policy factors when choosing management practices to minimize environmental impacts to soil and water quality, and in doing so support climate change mitigation efforts. Land trusts have an important role in protecting existing forests, reforesting areas, and reducing emissions from deforestation, which might be the alternative for the lands in question. Simply setting aside land for conservation, protecting it from development or degradation, can be a climate change mitigation strategy (

Huang et al. 2019). There is an opportunity to more strongly and effectively integrate climate change adaptation and mitigation actions that could lead to a more efficient allocation of financial funds to both kinds of projects, and reduction of trade-offs between various land use activities (

Locatelli et al. 2016).

Restoring highly ecologically sensitive lands can improve water quality (

Johnson et al. 2016), enhance wildlife habitat (

Hiller et al. 2015), reduce greenhouse gas emissions (

Gelfand et al. 2011), reduce soil erosion and nutrient loads (

Gleason et al. 2011), and limit potential flood damage (

Todhunter and Rundquist 2008). Reframing climate change adaptation strategies as modest changes to the on-the-ground land conservation work already being done may help lift the existing philosophical constraints or perceptions that are preventing climate change adaptation action now. This may result in an overall increase in land trusts involved in this work and overall community awareness, preparedness, and action.

Several facilitating factors were also identified that have led to climate change adaptation action in land trusts and could be used to encourage more action across Ontario. Collaboration between conservation organizations was identified as an important facilitator for climate change adaptation action. Our experiences suggest that this collaboration could consist of the sharing of resources and regular communication between these organization. Other studies have also found that collaboration between organizations can be an important opportunity for facilitating climate change adaptation actions such as a study in several North American landscapes including northern Ontario (

Lonsdale et al. 2017). This collaboration does not need to be just between conservation organizations. Relationships built between various kinds of actors including environmental NGOs, local governments, Indigenous communities, landowners, and scientists can be effective at mobilizing resources, broadening support, and more fulsome implementation in local contexts (

Russell et al. 2014;

Lonsdale et al. 2017). In addition, collaboration among agencies with neighboring jurisdictions can support regional efforts for climate change adaptation, as suggested by a study of two regions in Colorado and South Dakota, USA (

Lemieux et al. 2015).

Our experiences suggest that land trusts can benefit in their climate change adaptation planning from the use of tools that support the analysis of climate change vulnerabilities. Use of these tools can help shift priorities to account for potential climate change impacts, an important consideration when entering into conservation easements, a frequently used strategy for land trusts (

Rissman et al. 2015;

Owley et al. 2018). Application of these and related tools often is facilitated by collaboration between users when learning to use the tool and acquiring the required data. This collaboration requires users to communicate explicitly with each other about the study areas and clarify any inconsistencies in knowledge and understanding. In this way, using a tool can help users think more deeply about their climate change problem, even if they do not continue to use the tool afterwards. For instance,

Reiter et al. (2018) found that users of environmental decision support systems for climate change adaptation tended not to continue using the tools after their development phase. But the majority of end users valued the tools, and their experiences with the tools led them to engage in climate change adaptation actions and changed their understanding of climate change adaptation. Not surprisingly, though, continued user support by organizations that developed climate change adaptation tools has been identified as a factor leading to even greater success in facilitating change in climate change adaptation practices (

Reiter et al. 2019). While not addressed in our knowledge translation study thus far, building on the abovementionedorganizational support function, one of the end goals of the currently described knowledge translation process is the creation of a climate change adaptation community of practice under the guidance of OLTA, which is expected to lead to even greater gains for land trusts’ climate change adaptation.

6.2. Knowledge translation and organizational change

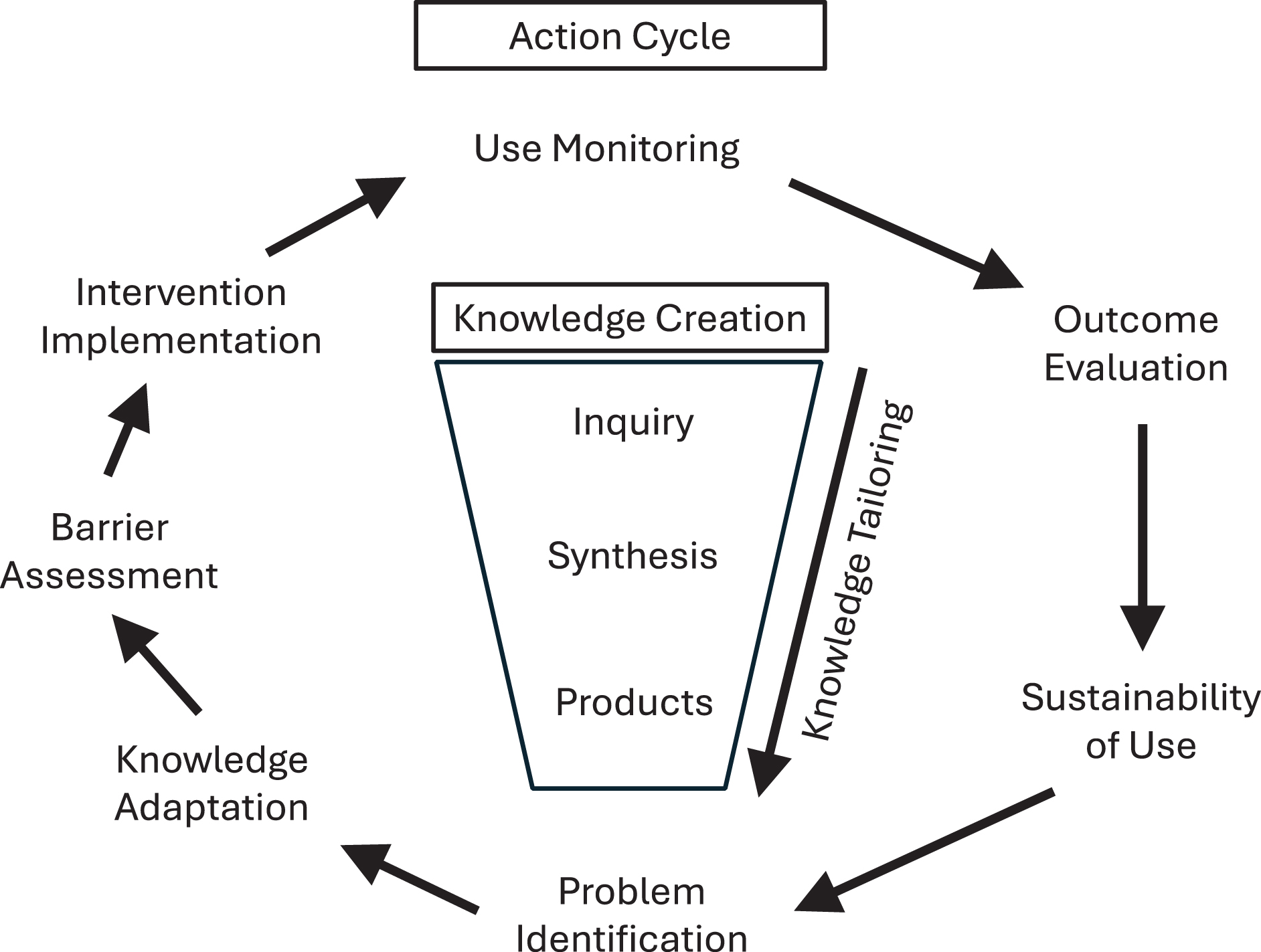

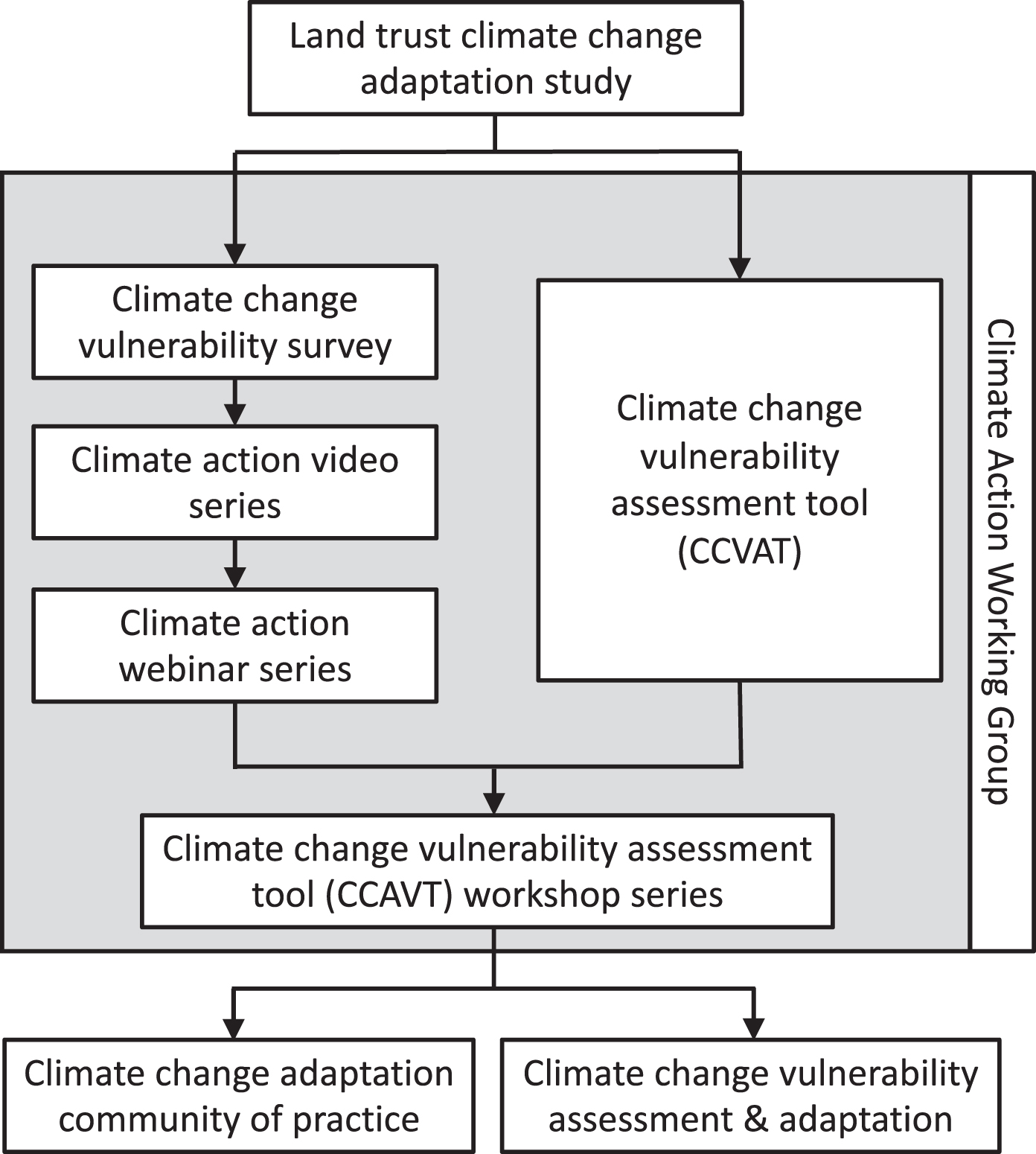

Our work is connecting with several elements of the Knowledge to Action Process Framework (

Graham et al. 2006). We have created a knowledge translation tool, the climate change vulnerability assessment tool (CCVAT), that has synthesized much of the available climate change knowledge for Ontario, and have cast it into a form that is tailored for the land conservation context. We have designed and implemented knowledge intervention initiatives aimed at increasing awareness and knowledge of climate change vulnerabilities and adaptation options for Ontario land trusts, as well as creating enabling situations that allow land trusts envision and plan climate change adaptation projects. Subsequently, we have worked with several land trusts to use their new knowledge about climate change vulnerabilities and adaptation and apply it in several pilot land conservation projects. Finally, we have started the process of spreading climate change adaptation knowledge further throughout the land trust community and promote its sustained use with initial steps at forming a community of practice (

Wenger 2011).

A considerable body of research exists that covers various aspects of the process of knowledge translation for better conservation decision-making. Often, this research identifies scientists who are creating research outputs that may be ill-suited for practical application as the reason for insufficient knowledge translation (e.g.,

Kharouba 2024). However, the responsibility for generating conditions under which practice-relevant knowledge can be created and exchanged, is shared by science producers and science users who need to work together (

Bisbal and Eaton 2022;

Ladouceur et al. 2022;

Cooke et al. 2023;

Bisbal 2024). A critical component in the Knowledge to Action Process Framework (

Graham et al. 2006) is the connection of knowledge creation to the action cycle. Well-adapted synthesis products are required for this connection to work, but this step requires user needs to be (made) known to scientists (

Cooke et al. 2023). Boundary organizations can help here by bridging between scientists and practitioners, serving as knowledge brokers, and producing boundary objects that facilitate knowledge exchange (

Kadykalo et al. 2021;

Bisbal and Eaton 2022).

The CCVAT, produced by OLTA as a boundary object to promote the uptake of climate change adaptation knowledge by land trusts, provided the abovementionedbridge between science and practice (

Cooke et al. 2023). The CCVAT thus presented the connection between knowledge creation and the action cycle in the Knowledge to Action Process Framework (

Graham et al. 2006). However, our results highlight that even under conditions of an identified science need (i.e., climate change adaptation by land trusts) and existence of a tailored boundary object (i.e., CCVAT), barriers for knowledge translation remained. The current knowledge translation project embraced learning of new evidence as a social process that engaged groups of researchers and practitioners (

Toomey 2023). But despite these favorable conditions, barriers were observed among land trusts relating to lack of resources, limited technical capacity and domain knowledge, as well as competing priorities.

The elements of the Knowledge to Action Process Framework (

Graham et al. 2006) that are less well developed in our work so far relate to the monitoring of climate change knowledge use and evaluation of the outcomes of knowledge use. However, the involvement of OLTA as a key stakeholder in the current knowledge translation work promises sustained momentum for this initiative. As a leading institution in the land trust movement in Ontario and in Canada, OLTA is well positioned to periodically reach out to member land trusts and other land conservation practitioners and inquire about their progress in climate change adaptation work. Current advice suggests that such inquiries should cover quantitative and qualitative data collection approaches, where quantitative data offer the possibility of generalizing results while qualitative data can indicate deeper meaning and provide contextual information (

Straus et al. 2010). The results from this inquiry could then be used to influence how climate change adaptation knowledge might be further translated and applied in the land conservation sector into the future.

The next steps for increasing climate change preparedness of the Ontario land conservation sector include the continued sharing of resources and tools with the community through webinars and workshops. While OLTA represents the interests of Ontario land trusts, it also draws much interest from other land conservation practitioners that regularly participate in OLTA activities and make use of OLTA resources. An important facilitator will be to secure funding that can be used to improve the existing climate change adaptation tool. For instance, the accessibility of the tool could be increased by creating a general user interface that reduces as much as possible any requirements for prior knowledge and experience with computing software. Also, the knowledge database that is underlying the tool could be continuously expanded with newly emerging scientific information (e.g., new downscaled climate change projections or species ecological information) and experiential information contributed by land conservation practitioners, as is possible with some other conservation decisions-making tools (

Margoluis et al. 2013;

Christie et al. 2022;

Cooke et al. 2023).

Other uses for additional funding might include actions to overcome capacity limitations in the land conservation sector, for example through a dedicated climate change adaptation outreach position. Such a position could be housed by a regional or national land conservation organization such as OLTA or the recently formed Alliance of Canadian Land Trusts. Other steps that can help overcome challenges for climate change adaptation include fostering a community of practice to increase the use of shared resources, communications between organizations, and access to background literature and studies. As well, collaboration with other organizations across sectors (e.g., governmental conservation agencies) may help overcome institutional limitations and facilitate regional climate change adaptation (

Lonsdale et al. 2017). Finally, collaboration might be beneficial across jurisdictions, such as with the Land Trust Alliance in the USA, which has well-established climate change tools and programs in place that could be adapted to the Ontario context and applied here (e.g.,

Water Words that Work 2018).