Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI), a mild or moderate form of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), is characterized by intense inflammation and pulmonary edema. The clinical picture involves a reduction of lung compliance, dyspnea, and increased hypoxemia and ventilatory effort (

Mowery et al. 2020;

Saguil and Fargo 2020). In addition, the inflammatory cells that migrate into the lung generate changes in their functions and morphological features, complicating treatment (

Grommes and Soehnlein 2011;

Fei et al. 2019). For that reason, this disease is responsible for about 200 000 cases in the United States and has a high morbidity and mortality rate in critical patients. The cellular mechanism involved is related to the high production of inflammatory cytokines, e.g., tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8, the activation and chemotaxis of macrophages and neutrophils, as well as the formation of free radicals, which assist in the persistence of the inflammatory picture (

Robb et al. 2016;

Mowery et al. 2020). It is considered an inflammation of difficult control and difficult diagnosis with little information about its development. However, ALI can progress during different phases, becoming a complex pulmonary syndrome with a broad spectrum (

Lin et al. 2018).

Several predictive models have been used to assess the severity and outcomes of ALI, as well as its complications. Among them, the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation score considers acute and chronic physiological variables to predict mortality, and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score evaluates organ dysfunction and is a reliable predictor of mortality (

Knaus et al. 1985;

Vincent et al. 1996). Additionally, the Lung Injury Prediction Score is used to predict the risk of developing ARDS in hospitalized patients, while the Berlin definition categorizes ARDS severity based on clinical and gasometric criteria (

Ranieri et al. 2012). Common complications associated with ALI include respiratory failure, multiple organ dysfunction, and secondary infections, which are efficiently predicted by these models (

Gajic et al. 2011;

Ranieri et al. 2012). Furthermore, individuals recovering from ALI may experience long-term physical and mental health impairments that affect their quality of life (

Fan et al. 2014;

Huang et al. 2016). Readmissions may be necessary, and hospital costs per person are estimated to range from $8476 to $547 974 (

Boucher et al. 2022). Therefore, its prevention and the search for new therapeutical approaches become relevant strategies.

Thyroid hormones (TH) are crucial for individuals’ development and physiological metabolism, also causing severe pathologies when thyroid dysfunction occurs (

Mullur et al. 2014). L-thyroxine is considered a gold standard in treating hypothyroidism. In addition to affecting life quality, the hypothyroidism can also cause an inflammatory clinical picture that seems to be positively modulated by this hormone (

Tellechea 2021). In an experimental model, a treatment performed with L-thyroxine in rats with hypothyroidism showed a reduction in inflammatory mediators such as C-reactive protein, IL-6, and TNF-α (

Abbas and Sakr 2016). Other evidence with L-thyroxine demonstrated modulation in the proliferation of macrophages, migration, senescence, and secretion of inflammatory factors, in addition to improvements in memory deficits and oxidative stress (

Ning et al. 2018;

Bavarsad et al. 2020).

There are inflammatory aspects common to both hypothyroidism and ALI. Hypothyroidism is characterized by elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines, factor also present in ALI. L-thyroxine may potentially exert a beneficial anti-inflammatory effect in ALI, by normalizing the elevated cytokine levels, as it does in hypothyroidism. Besides, the symptoms and complications of hypothyroidism, such as fatigue, cardiovascular diseases, and musculoskeletal issues (

Magri et al. 2010;

Chaker et al. 2017), are conditions that patients with ALI, especially those in intensive care units for extended periods, may also experience. Therefore, we decided to investigate whether pre-treatment with L-thyroxine, a widely used medication, could reduce inflammatory levels in ALI.

Additionally, the physical exercise (Ex) is a viable and widely recommended option to assist drug treatment. This natural resource has shown benefits in the prevention and adjuvant treatment for individuals with various diseases and age ranges (

Booth et al. 2012;

Sáez de Asteasu et al. 2019;

Martha et al. 2021). Chronic aerobic exercise has been extensively studied and proven to be effective in improving overall health and enhancing the immune system. It is known to induce beneficial adaptations, including enhancing the body’s antioxidant capacity, reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and increasing the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (

Bruunsgaard 2005;

Gleeson et al. 2011). These changes are crucial for modulating inflammation and preparing the body to combat severe inflammatory conditions, such as ALI. Also, Ex has been increasingly studied, especially in experimental models for combating ALI (

Gholamnezhad et al. 2022) and sepsis (

Wang et al. 2021).

From this perspective, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of L-thyroxine in Raw 264.7 macrophages stimulated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and their association with Ex in a mouse model of ALI. Considering that L-thyroxine is an essential hormone to maintain body homeostasis and that Ex acts systemically in the organism, we hypothesized that pre-treatment with L-thyroxine and its association with Ex could mitigate the inflammation caused by LPS, modulating the inflammatory response.

Materials and methods

In vitro cell culture

The RAW 264.7 (CLS Cat# 400319/p462, RRID:CVCL_0493) cell line from the ATCC bank (Virginia, USA) was cultivated in Eagle medium modified by Dulbecco (DMEM; GibcoTM, Life-technologies, USA) medium and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; GibcoTM, Life-technologies, USA) and the antibiotics penicillin and streptomycin (10 000 units/mL, GibcoTM, Life-technologies, USA) at 50 units/mL at 37 °C in an incubator moistened with 5% CO2. All experiments were performed in triplicate and only cells that did not exceed 12 passages were used.

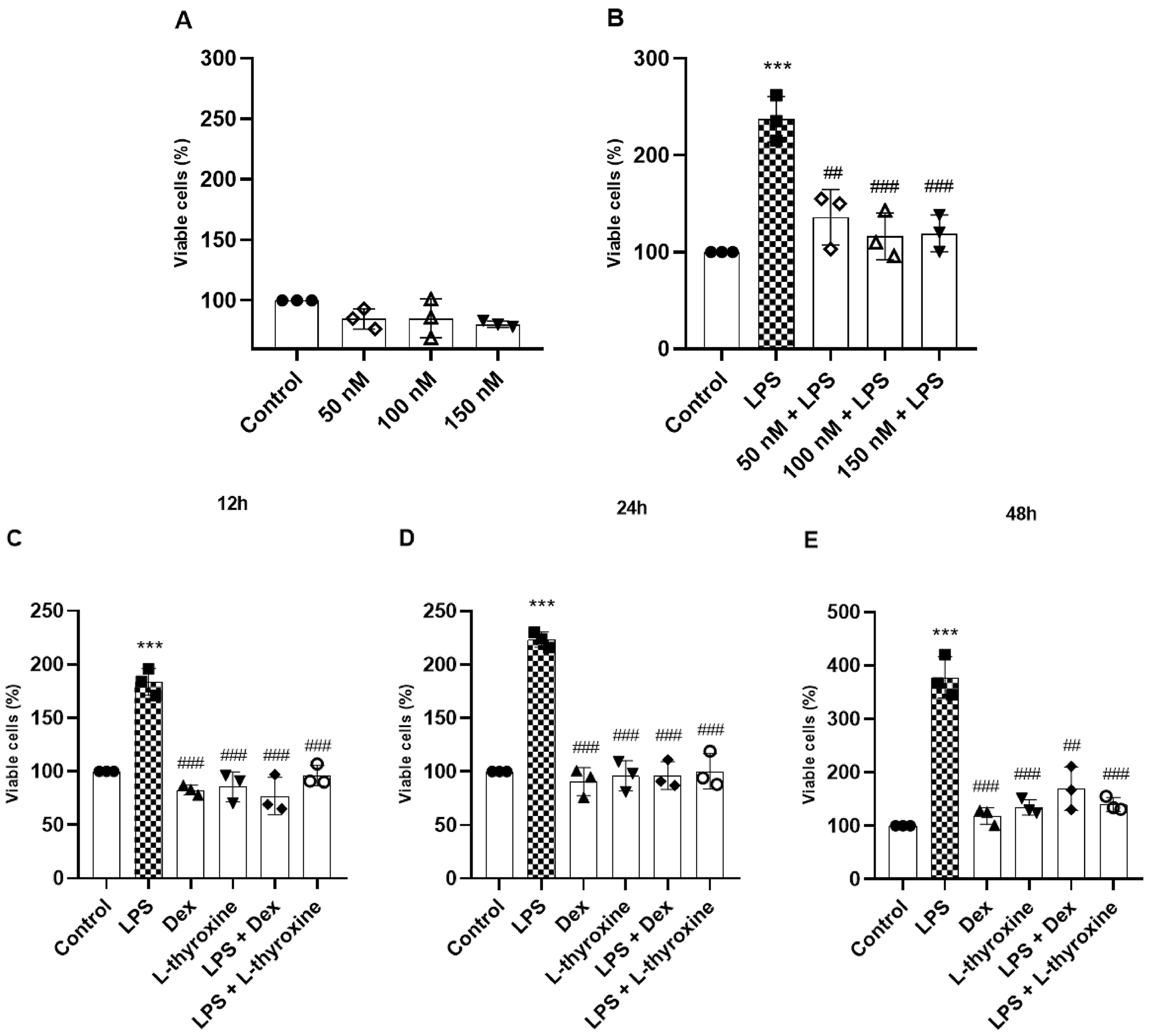

Preparation and pre-treatment with L-thyroxine

The stock solution of L-thyroxine (Sigma–Aldrich, USA) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Merck, USA) and then diluted in DMEM at different concentrations (50 nmol/L- 150 nmol/L). These concentrations were used according to

Ning et al. (2018). The RAW 264.7 cells were distributed into 6–24-well plates according to each experiment. After 24 h, the cells were pre-treated with these different concentrations of L-thyroxine for 1 h. Subsequently, the cells were activated with 1 µg/mL of LPS (

Escherichia coli 026: B6, Sigma–Aldrich, USA) for 12 h. Next, the cells were collected for the analyses described below, which assisted in the choice of the therapeutical and study concentration of L-thyroxine. Dexamethasone (Dex; Sigma–Aldrich, USA) was used as the positive control in the tests (10 µmol/L).

Cell viability assay

The effect of L-thyroxine on cell viability was evaluated through the bromide of 3-[4,5- dimethyl thiazole -2-il]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium (MTT; Sigma–Aldrich, USA) assay. The cells were distributed into 24-well plates containing 0.6 mL of DMEM. MTT was added into all plate wells and the plates were incubated for 3 h. Next, the supernatant was discarded and DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals produced by MTT. The optical density was read in an ELISA microplate reader (EZ Read 400; Biochrom, USA) at the wavelengths of 570/620 nm.

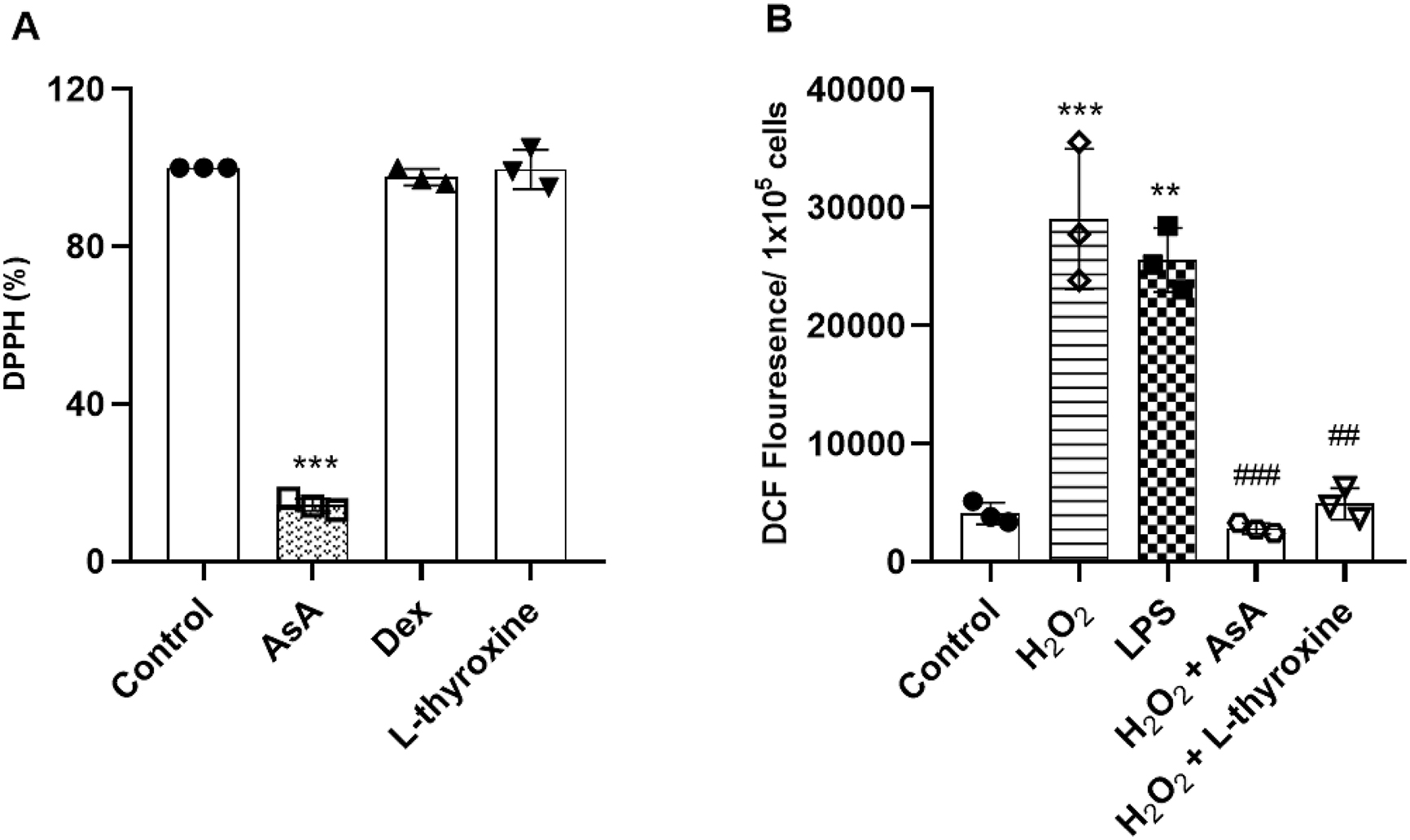

Antioxidant activity

The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH; Sigma–Aldrich, USA) method was used to determine the antioxidant activity percentage of L-thyroxine. DPPH is a purple, stable free radical that can be reduced in the presence of an antioxidant molecule, giving origin to a colorless solution. Ascorbic acid (AsA; 550 µg/mL; Sigma–Aldrich, USA) was used as a positive control. The optical density was measured at 515 nm using an ELISA microplate reader (

Kedare and Singh 2011).

Evaluation of the reactive oxygen species

The diacetate of 2′,7′- dichlorofluorescein (DCFH-DA; Sigma–Aldrich, USA) assay was performed to evaluate the generation of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). The DCFH-DA is a non-fluorescent compound that, when oxidated by ROS, becomes fluorescent and gives origin to 2′,7′- dichlorofluorescein (DCF; Sigma–Aldrich, USA) (

Kalyanaraman et al. 2012). Next, 1 × 10

5 cells were cultivated and treated with L-thyroxine (150 nmol/L), hydrogen peroxide (100 umol/L) or LPS (1 ug/mL). Ascorbic acid (550 µg/mL) was used as an antioxidant control. Later, cells were washed twice with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and incubated with 10 µmol/L of DCFH-DA at 37 °C for 30 min. The fluorescence intensity was measured by VICTOR® microplate reader (PerkinElmer, USA) at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and at an emission wavelength of 520 nm.

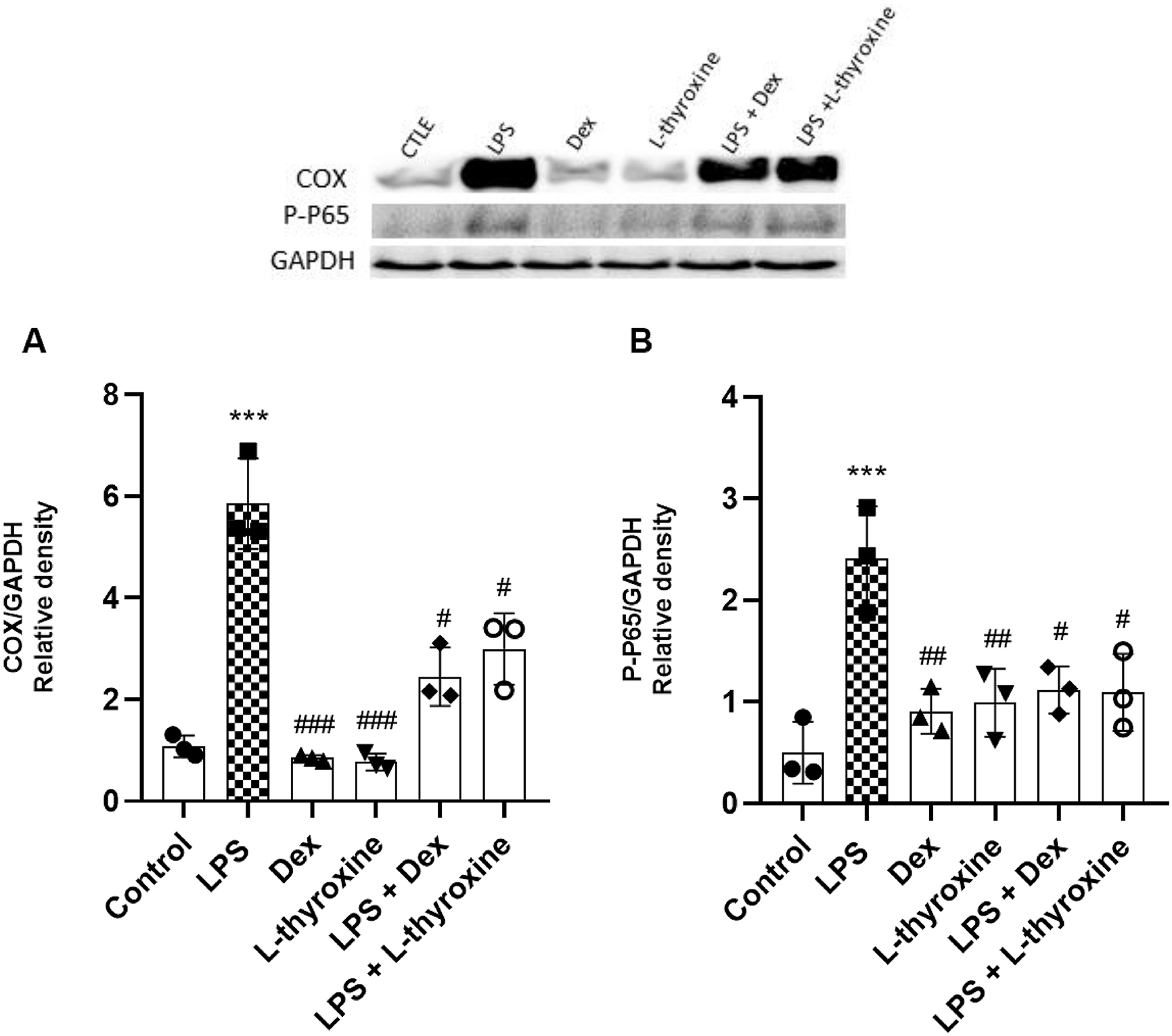

Western blot

The cells were seeded in 6-well microplates and then lysed with a specific buffer containing protease inhibitors. The total protein concentration in the samples was measured with a NanoDrop Lite spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). Aliquots from each sample contained equal amounts of protein (50 µg), which ran in 10% polyacrylamide gel (SDS-page) and were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (California, USA). Soon after, the membranes were blocked with a buffered saline solution and skim powdered milk for 1 h. Next, the material was incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibodies anti-NFκB p-p65 (1:250, Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 3033, RRID:AB_331284) anti-COX-2 (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 12282, RRID:AB_2571729) and anti-GAPDH (1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# 39-8600, RRID:AB_2533438). Subsequently, the blots were incubated with the secondary antibody anti-IgG (1:2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) for 2 h. The protein bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Lifescience). Band quantification was performed using the software ImageJ.

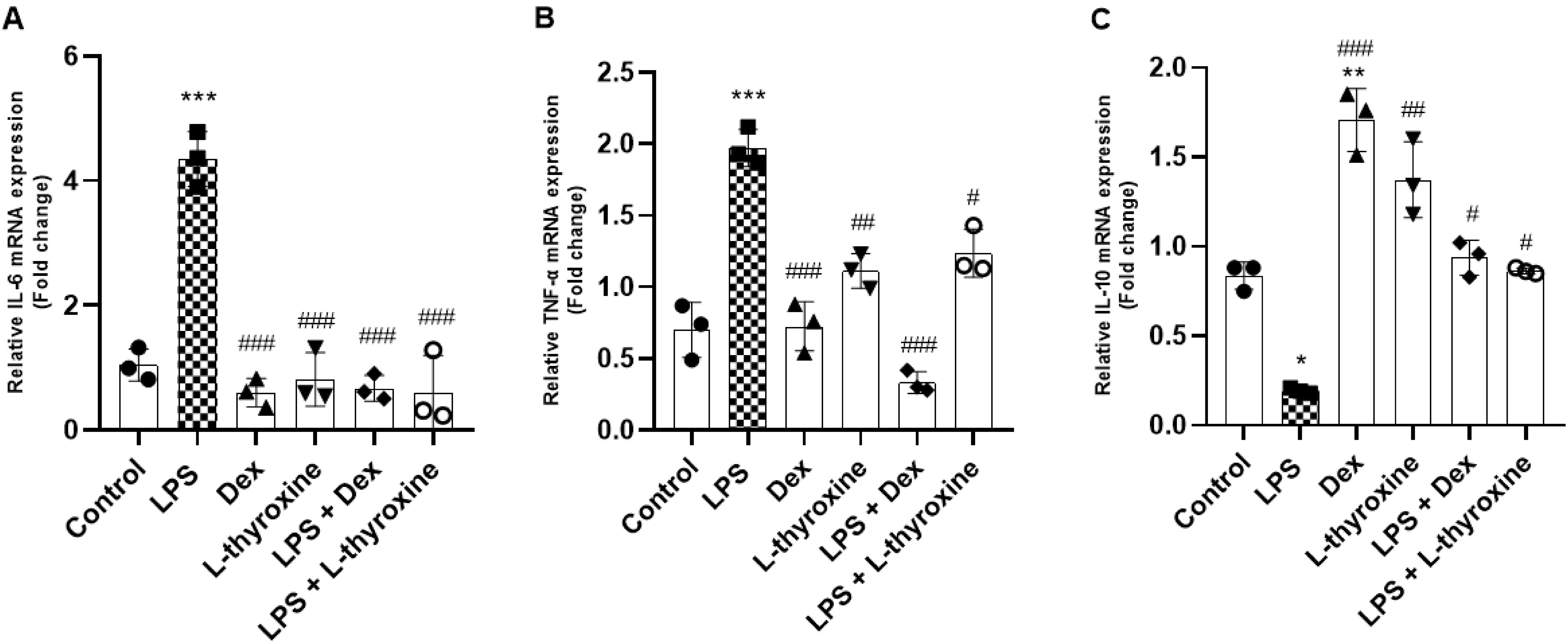

Gene expression

The cells were distributed into 6-well microplates containing 2 mL of DMEM, and the total RNA of the cell culture was obtained using Trizol (Invitrogen- Massachusetts, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Next, cDNA was synthesized through reverse transcription using a commercial kit Goscript

TM Reverse Transcriptase (Promega, USA) with 5 µg of total RNA for each sample. The real-time (RT-qPCR) reactions were performed using an SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; Thermo-Fisher Scientific, USA) to identify the synthesis of double strands in the reaction. Beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) was used as an endogenous control. The relative expression of mRNA was calculated using the ΔΔCq method (

Livak and Schmittgen 2001). The sequence of primers used was: B2M, forward, 5′-CCCCAGTGAGACTGATACATACG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CGATCCCAGTAGACGGTCTTG-3′; TNF-α, forward, 5′-ATAGCTCCCAGAAAAGCAAGC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CACCCCGAAGTTCAGTAGACA-3′; IL-10, forward, 5′-GCCAAGCCTTATCGGAAATG-3′ and reverse, 5′-AAATCACTCTTCACCTGCTCC-3′; IL-6, forward, 5′-TGGAGTCACAGAAGGAGTGGCTAAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTGACCACAGTGAGGAATGTCCAC-3′. RT-qPCR was performed with an initial step of 20 s at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles with 10 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C. The melting curve profile of the PCR products was obtained after an initial step of 15 s at 95 °C, followed by an incubation at 60 °C for 1 min (for reannealing) and heating of 0.3 °C/s to 95 °C.

In vivo experiments in animals

The study was carried out with male C57BL/6 mice (RRID: MGI:2159769). All studied animals were between 8 and 12 weeks old, weighed between 23 and 25 g and were provided by the Center for Experimental Biological Models of the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS). To achieve a more precise control of variables, it was decided to use male mice. Hormonal levels can influence the inflammatory response, and male mice tend to have more stable hormonal levels compared to females, which undergo reproductive cycles. The animals were split into groups of five per cage (22 cm × 16 cm × 14 cm), over shelves at a controlled temperature (24 ± 2 °C), a light/dark cycle of 12 h, with free access to food and water, and were acclimated for a week before the study. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation of PUCRS (number 9611). All experiments were conducted following the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Methodological approach and ALI induction

The animals were split and handled according to their experimental groups as described below:

1.

Control: The mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and intranasal (IN) PBS was administered. Next, DMSO was administered via the intraperitoneal (IP) route.

2.

ALI: The mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and received LPS via the IN route (2 mg/kg) to induce ALI (

Haute et al. 2023).

3.

ALI + Dex: The mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and received LPS via the IN route. Next, Dex (1 mg/kg) was administered via the IP route (

Tu et al. 2020).

4.

ALI + L-thyroxine: The mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and received LPS via the IN route. Next, L-thyroxine (30 µg/kg) was administered via the IP route. The concentration chosen was based on the proportion of the animal’s weight, according to previous studies with L-thyroxine and the treatment time adapted to the ALI induction protocol (

Seyedhosseini Tamijani et al. 2019;

Bavarsad et al. 2020).

5.

Ex + ALI: The mice performed Ex for five weeks and were then anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and administration of LPS via the IN route.

6.

Ex + ALI + Dex: The mice performed Ex for 5 weeks and were then anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and IN administration of LPS. Next, dexamethasone was administered via the IP route.

7.

Ex + ALI + L-thyroxine: The mice performed Ex for five weeks and were then anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and IN administration of LPS. Next, L-thyroxine was administered via the IP route.

The mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (0.4 and 0.2 mg/g, respectively) 12 h after ALI induction and euthanized by exsanguination through cardiac puncture. Next, the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and lung tissue samples were collected.

Exercise

Animals from groups Ex + ALI; Ex + ALI + Dex; and Ex + ALI + L-thyroxine were submitted daily to an exercise session on a motorized treadmill, during the 5 weeks that preceded the day of ALI induction. The animals were familiarized with the treadmill in 10 min sessions at a speed of 5 m/min for one week to reduce stimuli related to handling and the environment. Initially, the brisk walk speed and time were 10 m/min, being 20 min/day on the first day with an increment of 10 min/day until reaching 60 min/day, to reach an exercise intensity of approximately 70% of maximum oxygen consumption (VO

2) of the animals. After that, exercise sessions at a speed of 10 m/min for 60 min, 5 days a week, were used (

Wu et al. 2007). Before starting the protocol, the animals were habituated to the room for 30 min. No stimulus, such as an electric shock, was applied to motivate the animals to brisk walk. Animals that refused to brisk walk, presented any visual sign of distress, or had any difficulty to follow the protocol were exclude from the study.

Bronchoalveolar lavage sampling

The animals were previously anesthetized (0.4 mg/g ketamine and 0.2 mg/g xylazine), and BAL sampling was performed by applying an injection and aspiration of 1 mL of PBS containing 2% SFB (process performed twice) using a tracheal cannula initially placed into the animal.

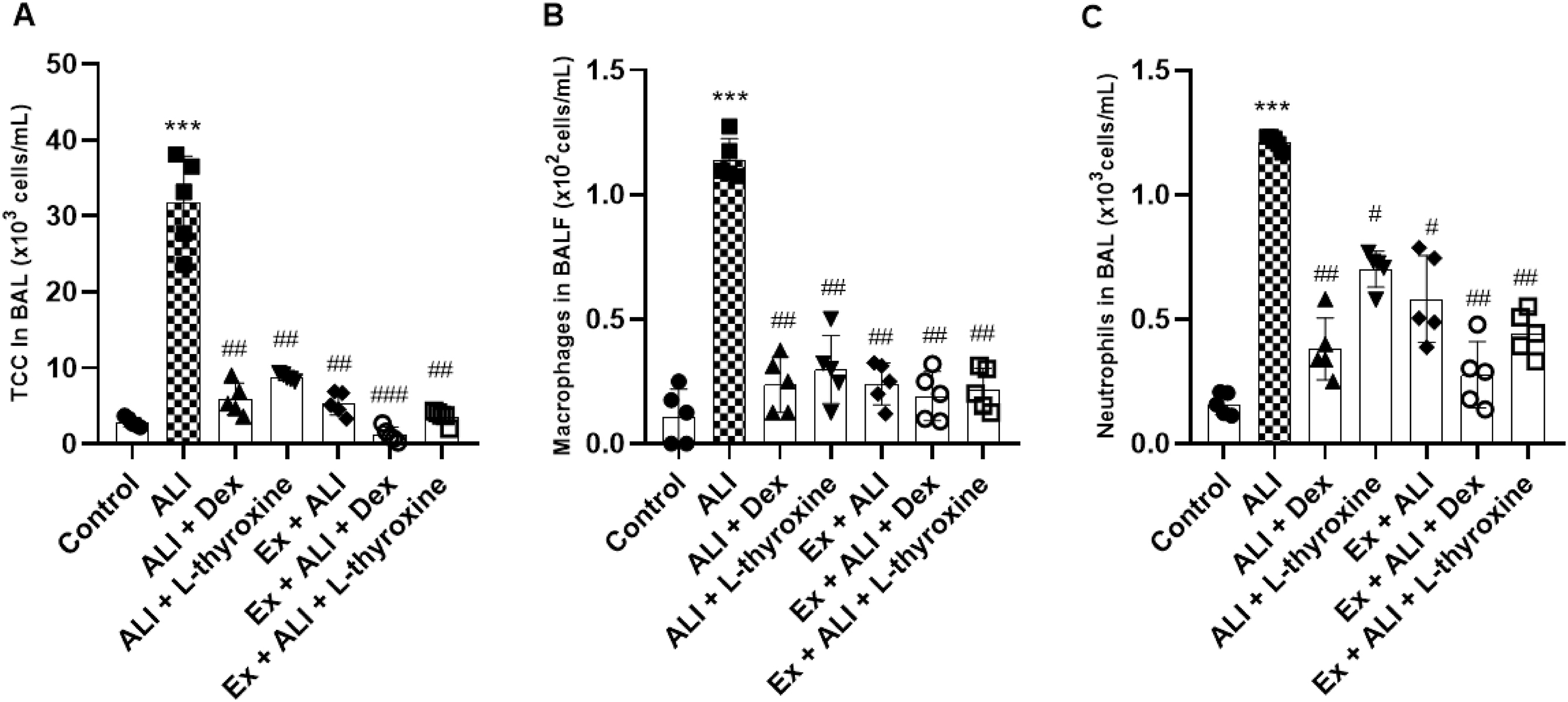

Total and differential cell count

The BAL material collected was centrifuged (1000 × g for 10 min) and the supernatant was reserved. The cell pellet was diluted with 350 µL of PBS to perform the counts. The exclusion method with Trypan blue in a Neubauer chamber (Boeco, Germany) allowed performing the total cell count and calculating cell viability. Slides were prepared to evaluate the differential cytology of inflammatory cells using 80 µL of cell material previously diluted with PBS in a centrifuge (FANEM, São Paulo, Mod. 218) at 500 rpm for 5 min. Next, the slides were fixed in ambient air and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Panótico Rápido; Laborclin, Brazil). The different cell types were analyzed by optical microscope and, after counting 400 cells, the relative and/or absolute numbers were expressed.

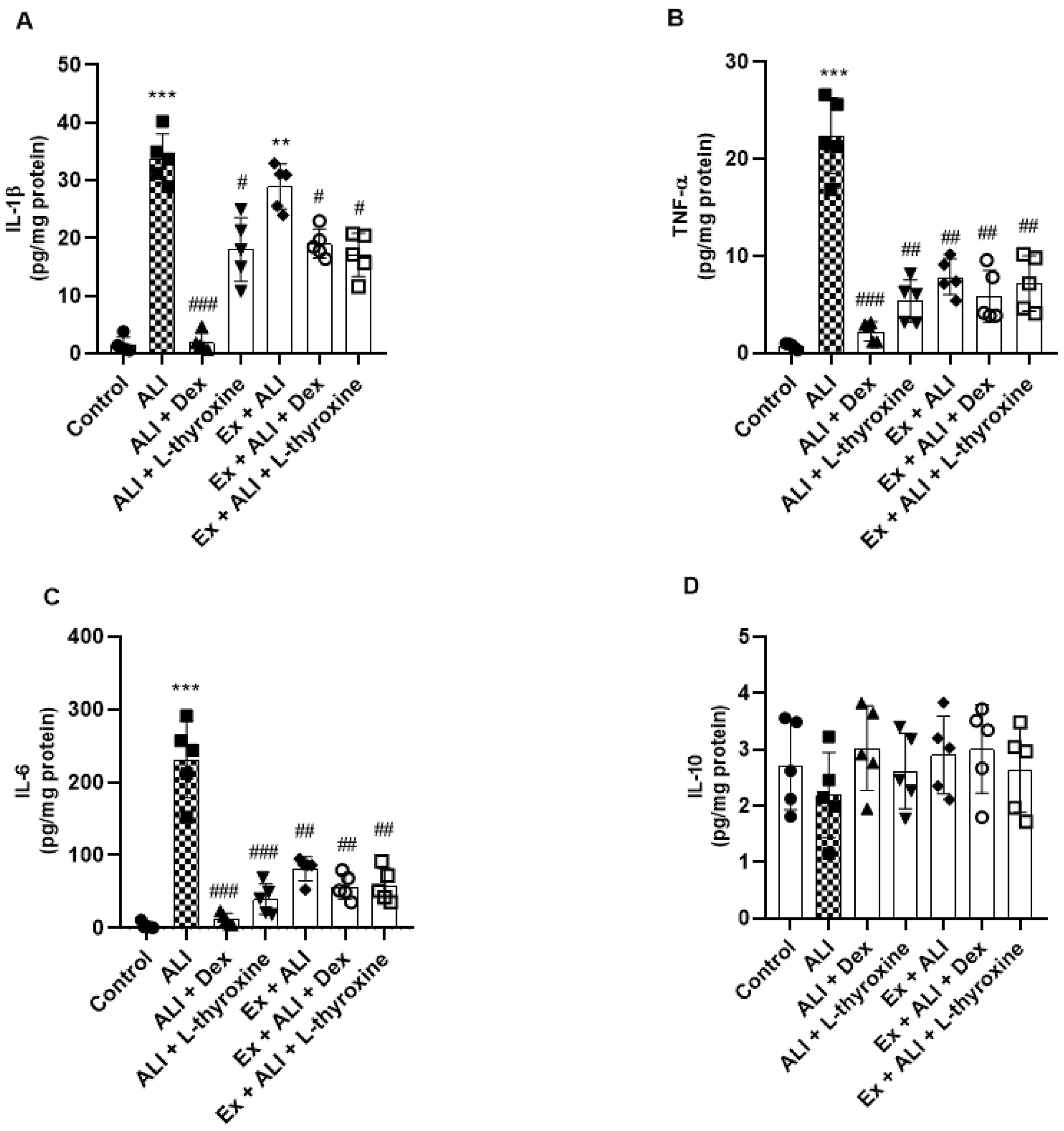

Cytokine quantification

The lung tissue samples were collected and macerated with a PBS solution. The simultaneous quantification of cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 was performed using ProcartaPlex (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in the MagPix device (MILLIPLEX®), and the software xPONENT® 4.2 (MILLIPLEX®) was used to analyze the data generated.

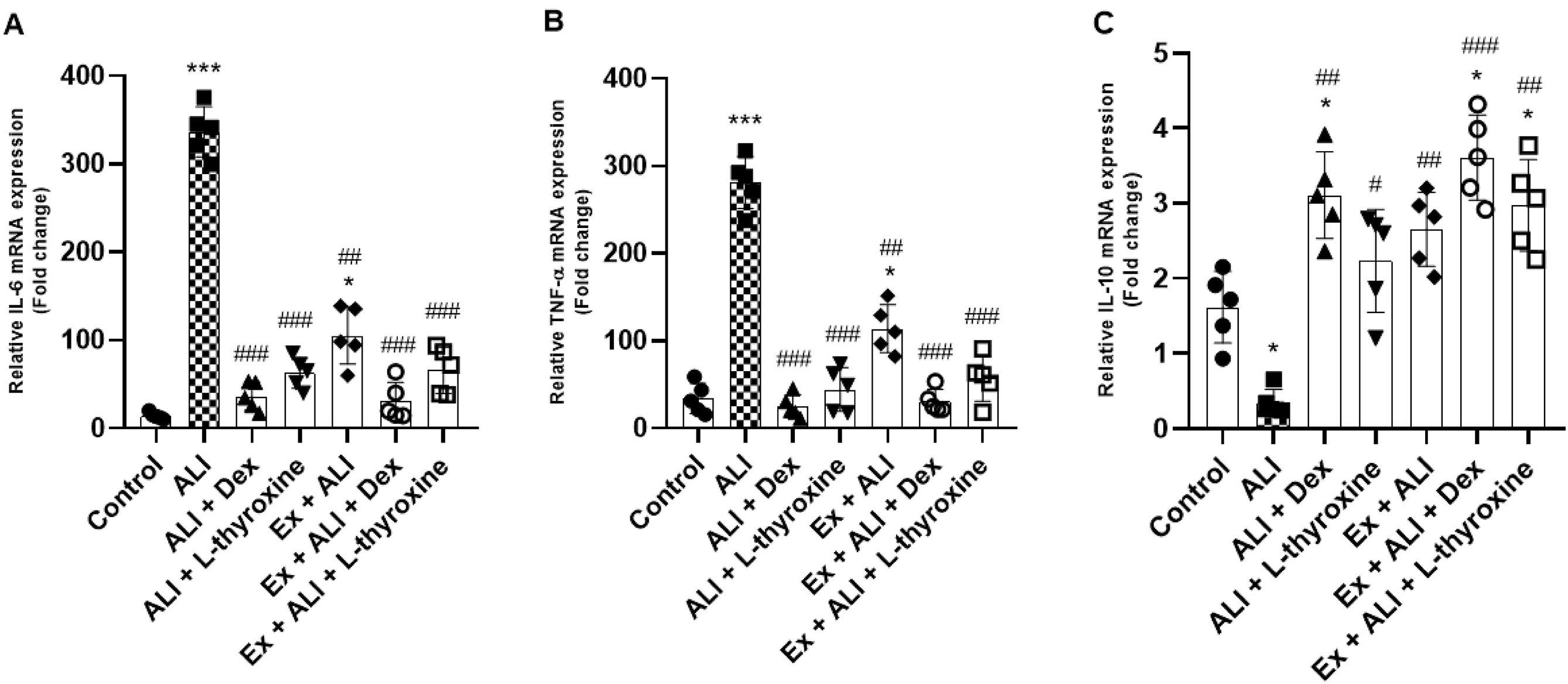

RNA and RT-qPCR extraction from lung tissue

After euthanasia, the lung tissue was separated and stored in an ultra-freezer (−80 °C) for RNA extraction. The total RNA was extracted from all samples using Trizol, following the manufacturer’s recommendations. cDNA synthesis and RT-qPCR were performed as mentioned in the “Gene expression section” section, using the same primers and methods.

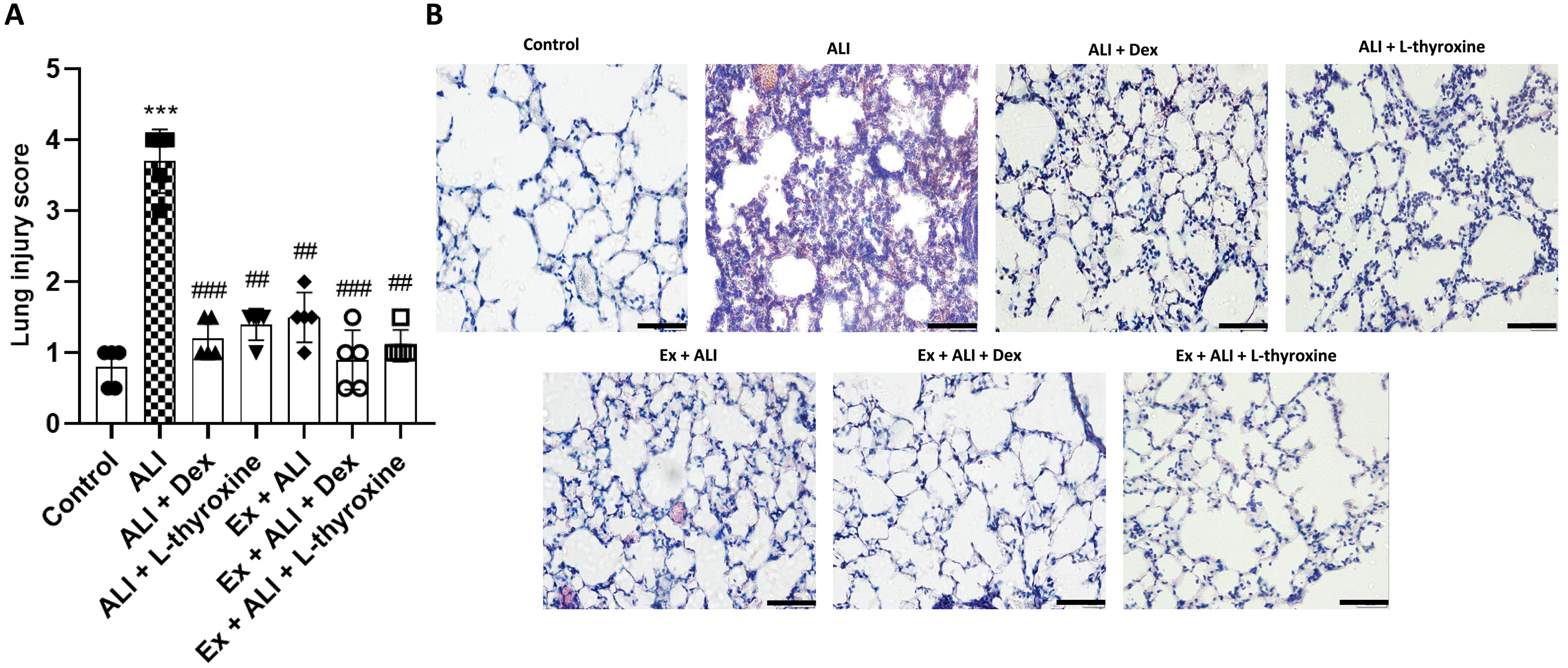

Histopathological analysis of lung tissue

For this procedure, 10% formaldehyde was used in the lung tissues, after which they were stored for 24 h in formalin. Next, the tissues were embedded with liquid paraffin, and, after that, the slides were produced with 4 µm thick histological sections. Later, H&E staining was performed to identify the inflammatory infiltrate. The changes in lung tissues were assessed through a semiquantitative evaluation approach (

Zhang et al. 2017). In summary, histological criteria were blindly assigned to measure the severity of pulmonary inflammation, including interstitial inflammation, infiltration of inflammatory cells, congestion, and edema. The histopathological assessments ranged from 0 (normal state) to 4 (severe grade) and were determined by averaging the assessments assigned to each individual mouse in their respective groups. The images were captured with a DP73 camera coupled to a light microscope BX43 (Olympus, Japan).

Statistical analysis

At first, we conducted in vitro experiments with RAW 264.7 cells, performing three independent experiments in triplicates to evaluate whether our hypothesis about the ability of L-thyroxine to reduce inflammation was warranted or not. Then, we presented the results obtained with the animals (in vivo) as mean ± standard deviation (SD). We used five animals per group with the aim of minimizing the need for animals in research, in strict adherence to ethical considerations that promote the right to life and animal welfare, while ensuring the validity of the results. Studies with similar approaches have also adopted a comparable sample size (

Scheffer et al. 2019;

Jin et al. 2020). Data were expressed as mean ± SD and were analyzed by one-way Analysis of variance (ANOVA).

P < 0.05 was defined and considered statistically significant. Subsequently, Tukey’s post-test for multiple comparisons was performed. All statistical analyzes were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, CA).

Discussion

Our results demonstrated that pre-treatment with L-thyroxine positively regulated the inflammatory response in macrophages stimulated by LPS. Since the lung is one of the most affected organs by the release of pro-inflammatory mediators during sepsis (

Winters et al. 2010) and trauma (

Pierce and Pittet 2014), we decided to investigate whether L-thyroxine could cause a protective effect in an ALI model induced by LPS. Furthermore, we included Ex as it is recommended to assist in treating hypothyroidism symptoms (

Werneck et al. 2018) and there is evidence of its beneficial effects in ALI (

Gholamnezhad et al. 2022). Thus, we evaluated the effects of L-thyroxine in association with Ex on the inflammatory levels of mice with ALI. Although the anti-inflammatory effects shown by L-thyroxine were not summed to those of Ex, our results indicate that combining L-thyroxine with Ex was beneficial against the lung inflammation caused by LPS. Therefore, we demonstrated, for the first time, the capacity of L-thyroxine in modulating mechanisms related to ALI and its effects in association with Ex in ALI induced by LPS.

The RAW 264.7 cell line has been widely used to investigate in vitro inflammatory function, particularly due to its response to LPS, which promotes the release of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α (

Tang et al. 2019;

Yi et al. 2019). Our results corroborate these findings, demonstrating that exposure to LPS significantly increased the levels of these cytokines. Additionally, we observed that LPS stimulates the generation of ROS, consistent with literature evidence (

Baek et al. 2020). We found that L-thyroxine, although not demonstrating antioxidant activity via the DPPH method, reduced ROS formation in RAW 264.7 cells exposed to H2O2. These findings are supported by studies indicating that hypothyroidism increases ROS production (

Santi et al. 2010;

Cheserek et al. 2015) and L-thyroxine treatment normalizes this production (

Chakrabarti et al. 2016).

Furthermore, L-thyroxine modulated the inflammatory response by reducing the expression of Cox-2 and the phosphorylated subunit of NF-kB, p-p65, which are crucial regulators in the inflammatory process. Selective Cox-2 inhibition is a well-established mechanism of action for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (

Zarghi and Arfaei 2011) and NF-kB activation is a fundamental pathway in inflammatory response (

Liu et al. 2017). Our results indicate that L-thyroxine may exert a significant anti-inflammatory effect by interfering with these mechanisms.

As described by

Qin et al. (2016), LPS exposure elevates mRNA expression of IL-6 and TNF-α in RAW 264.7 cells. In our study, L-thyroxine demonstrated the ability to reduce these increases. Interestingly, L-thyroxine did not increase IL-10 mRNA expression but prevented its decline induced by LPS. This may be attributed to the action of TH, including L-thyroxine, in maintaining organismal homeostasis (

McAninch and Bianco 2014) and modulating immune responses (

De Vito et al. 2012).

In the literature, it is documented that inflammatory cytokines and C-reactive protein are elevated in hypothyroidism (

Tayde et al. 2017;

Tellechea 2021) and L-thyroxine treatment normalizes these levels (

Marfella et al. 2011), indicating a positive role in stabilizing the immune response. Experimental models show anti-inflammatory actions of TH and their receptors (

Chen et al. 2012;

Furuya et al. 2017). In critically ill patients with sepsis, low levels of circulating L-thyroxine are found in plasma (

Al-Abed et al. 2011), yet the role of TH in innate immune response remains poorly understood, with conflicting results (

Wenzek et al. 2022). In our ALI model, L-thyroxine, both alone and in combination with Ex, modulated the inflammatory response, decreased inflammatory mediators, and improved tissue function, which are significantly altered in ALI.

Previous studies indicate that exercise can alter the profile of pro and anti-inflammatory cytokines depending on its execution protocol (

Improta-Caria et al. 2021). In intensive care units, aerobic exercise on a cycle ergometer as early mobilization has been used to prevent delirium, reduce muscle loss, and improve lung function in critically ill patients, including those with ALI (

Aquim et al. 2019). These interventions reinforce the idea that physical exercise is not only safe but also beneficial in critical health contexts. Furthermore, the American Heart Association has published guidelines for primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases, recommending at least 150 min per week of moderate-intensity physical activity or 75 min per week of vigorous-intensity exercise (

Arnett et al. 2019), further encouraging regular exercise practice.

Moderate-intensity aerobic exercise on a treadmill has been shown to decrease IL-6 and TNF-α levels in both humans (

Abd El-Kader et al. 2013) and mice (

Lang et al. 2020) and our results confirm that moderate exercise can reduce IL-6 and TNF-α levels in mice. Additionally, we observed an increase in IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels in animals with ALI, which was significantly reduced with L-thyroxine pretreatment and in combination with exercise. Previous studies have identified elevated levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β associated with a worse prognosis in ALI (

Meduri et al. 1995;

Voiriot et al. 2017) and our findings corroborate the increase in these inflammatory agents in ALI. Gene expression also reflected these changes, with a reduction in IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA levels following pretreatments.

While we did not observe a significant difference in IL-10 through the ProcartaPlex assay, the combination of L-thyroxine with exercise increased IL-10 mRNA expression. This synergy is crucial, as both L-thyroxine and exercise alone were able to prevent IL-10 levels from declining but not to increase them. The ability of exercise to increase IL-10 levels (

Abd El-Kader and Al-Shreef 2018), combined with the effects of L-thyroxine, contributes to an increase in IL-10 mRNA expression in ALI, suggesting a beneficial combined action in modulating the inflammatory response.

Considering the correlation with humans, it is important to observe the effects in our study by performing training in the target zone of 70% of maximum VO

2 or maximum heart rate. However, for humans, this training zone is individual (due to factors such as fitness level, age, and comorbidities) and should be determined through a treadmill exercise test (

Fletcher et al. 2001) or using formulas based on the Karvonen model (

She et al. 2015). Therefore, the treadmill speed varies from person to person.

Although we observed a decreased in ALI in male mice, when pre-treated with L-thyroxine and Ex, the same should not be directly assumed for female mice as they could present different inflammatory responses. Our study was conducted with only male mice to minimize hormonal variability, since males exhibit more stable hormone levels compared to females, who experience hormonal fluctuations due to the estrous cycle, and to reduce initial behavioral and physiological variability (

Scotland et al. 2011;

Villar et al. 2011;

Bojalil et al. 2023). Additionally, inflammatory response methodologies usually employ male mice (

Gholamnezhad et al. 2022). We recognize that our approach limits the generalization of our findings to both sexes, and therefore our results serve as a basis for future studies that will include both males and females.