Description of coordinating structures and governance

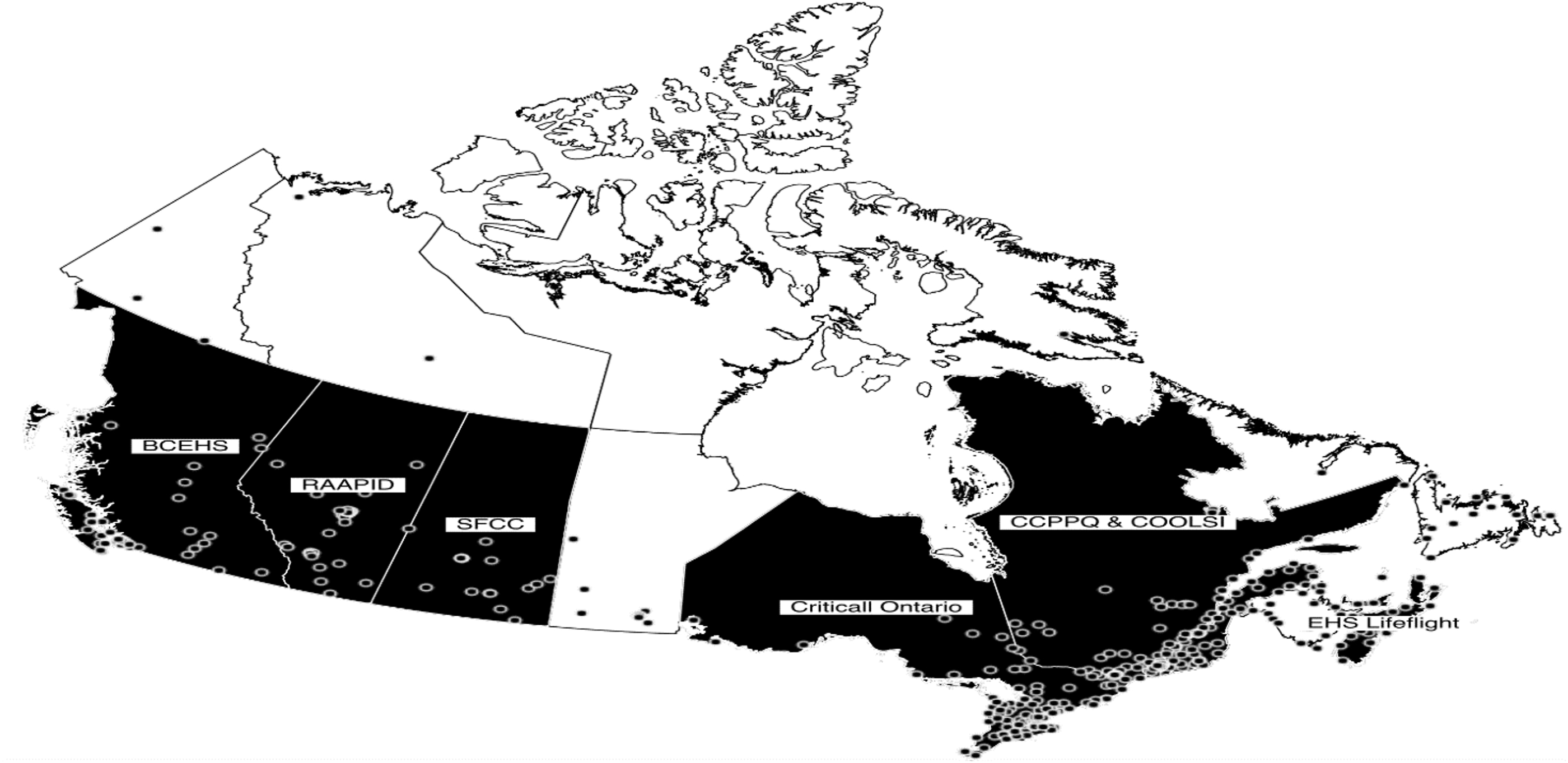

A global presentation of the coordination structures (territory served, number of transfers requests processed annually, years existence number, composition of governance team, guidelines, and category of patients) is shown in

Table 1. Canadian territories currently do not have coordination structures, which is an important result in itself.

Regarding the roles of the governance team and the associated responsibilities, it was reported that the medical director in CritiCall Ontario is involved in out of country repatriation and participates at provincial tables while following up with provincial physicians if needed. There are also medical associates that are available in real time to resolve any conflicts or issues that require additional support to the call center. The executive director ensures the lead strategy, operating plan, and managing budgets.

At the CCPPQ, responsibilities of the governance team included training staff, the formalization of decisional algorithms, periodic reports, analysis of issues, quality improvement, escalation of problems to expert groups, or territorial medical managers, etc. There are managers who are responsible to manage systems and teams, to participate in provincial discussions and tables, while involved in strategy and operating plan.

At RAAPID, physicians act as a dyad with the manager/director to support clinical elements of the processes and engagement. Managers have a background in nursing and support day to day operations, change management and strategy.

Alike RAAPID, COOLSI co-management with a director and a medical manager is responsible for strategic development. Director is responsible for human resources.

EHS Lifeflight is a provincially paid, private company. Governance is by a president/COO (was a nurse), director with a large portfolio (was a nurse + paramedic), and senior manager (who was a paramedic). Their structure includes a medical director.

It was reported that the SFCC management included paramedics instead of nurses. Nurses help triage connections between physicians for patient transfers. Managers oversee the coordination centre.

At the BCEHS, there are no nurses in the governance team. Medical directors are responsible for health authorities (six different health authorities in British Columbia). Each department has a manager and a physician lead. The physician lead oversees any new initiative from a medical perspective and sits on board meetings that require a physician lead. They also have physicians on call 24/7 to help with prioritizing transfer and ground support for paramedics (approx. 44 physicians).

As for the guidelines in place (

Table 1) and notably the mandatory use of the coordinating structure for the transfer of certain patients, BCEHS mentioned that all Life Limb and Threatened Organ patients or any patient that uses BCEHS resources should use the transfer coordination center in the eventuality of a transfer.

The CCPPQ indicated that it is mandatory for the transfer of at-risk pregnant women, newborns requiring intensive care and the reorientation of those under 18 years old requiring intensive pediatric care. The use of COOLSI is recommended for intensive care patients.

CritiCall Ontario indicated that it is mandatory for life-threatening or limb-threatening conditions. EHS Lifeflight reported that it was mandatory for transfer of neonatal and pediatric critical transfers. RAAPID answered that the PICU/NICU transfer teams were mandatory for neonatal and pediatric critical team transfers. The SFCC reported that it was mandatory in the transfer of trauma, critical and stroke cases.

Further, when asked if their coordination structure followed any other guidelines that were not listed among the options, the BCEHS reported that, with the exception of repatriations, the various subspecialties have their own specific guidelines developed by health authorities in collaboration with the BCEHS; COOLSI’s respondents reported resorting to the use of a coordinating physician when necessary. EHS Lifeflight reported triage amongst all services. RAAPID explained that they have specific call flows for different medical departments, to guide the regional placement of patient.

Processes

Regarding the services offered (

Table 4) for medical advice/tele expertise, it is provided by physicians from the structure at EHS Lifeflight, by physicians from the territory in five structures (BCEHS, CCPPQ, CritiCall Ontario, RAAPID, and SFCC) and by a physician from either the territory or from the structure in one case (COOLSI). Among the six structures that handled patient repatriation requests, the coordination of these transfers could be processed by clinical staff only in four (CCPPQ, COOLSI, EHS Lifeflight, SFCC), by nonclinical or clinical staff in RAAPID, by nonclinical staff in BCEHS. All structures except for COOLSI offered a certain level of specialized interhospital transport coordination.

Table A in Supplementary Material shows for which care units the various coordinating structures processed transfer requests. When asked if they performed interhospital transfer coordination for any other units, the BCEHS specified that it regularly handled transfer requests for all units except rehabilitation. The CCPPQ reported that it handled requests for the perinatology and pediatric units. RAAPID also could process urgent transfer requests from clinics and COOLSI reported that it took on psychiatry and rehabilitation center transfer requests only to face the pandemic situation. BCEHS elaborated that transfer requests were either classified as red, which were processed as soon as possible, yellow, in which the time was specified by admitting specialist, green, which were scheduled appointments, so the targets were to make their appointment or blue, which were patient repatriations for which there were no target; CritiCall reported that it had two priorities: life or limb, where the target was 10 min or urgent and emergent where the associated delay was 15 min. All structures except the CCPPQ and CritiCall Ontario had a process in place for the transfer of patients from specialized to less specialized services.

Three structures, the BCEHS, CritiCall Ontario, and RAAPID arrange transportation once the destination had been identified and the remainder does not. These structures that make transportation arrangements do so for ground, airplane, or helicopter transportation. Only the BCEHS has its own transport team, the other two working with external partners.

Regarding the type of information asked and collected during the transfer, it was reported that all structures collected information on the reason for transfer. Every structure except CritiCall Ontario collected information on patient vital signs. Every structure except for the BCEHS and CritiCall Ontario collected information on patients summary of hospital courses. The CCPPQ and EHS Lifeflight reported collecting information on medication lists. The CCPPQ and EHS Lifeflight also collected information on lab reports. It was also reported that BCEHS, COOLSI, and EHS Lifeflight collected radiological images during transfers.

Finally, when asked if any other information was asked during the transfer, the BCEHS reports that depending on the transfer, it collects information on infectious precautions, if there was trauma (if relevant), whether the patient is intubated or not. The CCPPQ responded that the COVID test results were asked; RAAPID also collected information on care needs, that is, need for isolation, transport needs, and safety concerns.

The modalities used for sharing clinical information are detailed in Table B (Supplementary Material) and those relating to the updates between transfer acceptance and patient transport are displayed in Table C (Supplementary Material).

We also inquired about the performance indicators for which the results are displayed in Table D in Supplementary Material. As for additional performance indicators used within their organization, the CCPPQ mentioned the number of transfers to measure performance; COOLSI indicated time to acceptance; CritiCall Ontario quoted time to first call out, time to patient acceptance, time of arrival, whether the patient is declared life or limb or not and whether the consultation was accepted or declined with the associated reason. Finally, the BCEHS reported calls in waiting/answered to determine if their services are meeting the level of demand. The measures in place to ensure continuous improvements are presented in Table E in Supplementary Material.

All but one of the structures (EHS Lifeflight) were reported to have changed their processes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. At the CCPPQ, the changes were the existence of COVID-19 designated centers, the implementation with COOLSI of an algorithm to organize who does what as well as in which context to call the COOLSI and higher accountability. At the COOLSI, the pandemic resulted in added responsibilities, as it also took on transfer toward regular wards, as well as rehabilitation and psychiatry patients, in addition to ministerial instructions regarding dedicated COVID centers and changes in capacity. CritiCall Ontario reported that they needed to stay on top of changes and processes as the need arose: they were at the Covid Command Table and involved in discussions, policy changes, and changes to level of authority for movement of patients. CritiCall Ontario was also involved with Saskatchewan and Manitoba in moving patients to Ontario and back to their provinces. In addition, CritiCall Ontario continued to support the re-opening and sustainability of the system and worked to finalize the redirect process for hospitals and regions. Finally, CritiCall Ontario was actively involved in several projects to further assist with rural needs and virtual care opportunities. RAAPID reported that more requests became coordinated within their structure, which was not mandatory, to improve communication and predictability of patient movement between sites, particularly those with COVID symptoms. Consequently, there was involvement of their team with increased frequency in more movements. The SFCC went from being a regional coordination structure to a provincial one.