1. Introduction

Brassica rapa (turnip) is an essential root and leaf crop cultivated worldwide and it belongs to the family

Brassicaceae which approximately consists of 35 000 species. Delicious roots and green leaves are the reasons for the cultivation of

B. rapa, its roots are used in making salads, and green leaves are consumed after cooking or steaming which are more beneficial for human health in comparison with turnip roots because the roots contain the least amount of phenolics (

Dejanovic et al. 2021). In addition,

B. rapa has some traditional beneficial effects like turnips are therapeutic agents for various types of liver and kidney diseases. Turnips have also pharmacological importance, they are antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antidiabetic, cardioprotective, nephroprotective, antitumor, and analgesic (

Paul et al. 2019). Studies show that turnips are rich in glucosinates, sulfur compounds, carbohydrates, e.g., polysaccharides, and minerals, e.g., calcium 4500 mg per kg, zinc 15.7 mg per kg, and iron 81.1 mg per kg (). They also contain vitamin C, flavonoids, isothiocyanates, phenolics, volatiles, and saponins, and the slices of turnip contain 61%–39% of essential and nonessential amino acids (

Sun et al. 2022).

Various pathogenic fungi drastically affect the growth and yield of different species of this plant. Some of

Brassica species’ common and most impacting fungal diseases are powdery mildew, downy mildew, Alternaria leaf spot, white rust, and blackleg. The combination of

Alternaria brassicae,

Alternaria japonica, and

Alternaria brassicicola causes the Black spot disease in

B. rapa which decreases the germination and causes shuttering of premature pods,

Albugo candida causes the white rust disease in

B. rapa to which 60% of the yield was lost in Canada. Powdery mildew is caused by the pathogen

Erysiphe cruciferarum in

Brassica crops and lost yield worldwide (USA, Australia, and European and Asian countries) (

Mourou et al. 2023).

Plants contain specified proteins designated as plant defensins (PDFs) to tackle such infections. These proteins are expressed in the cell wall of plant cells or extracellular spaces and are found in different parts of the plant such as seeds, leaves, flowers, roots, and stems (

Yao et al. 2019). PDFs are small cysteine-rich proteins mainly consisting of a cystine-rich domain, a variable region on the C-terminal, and a signal peptide on the N-terminal (

Yao et al. 2019). In

Arabidopsis thaliana, two families of PDFs were identified (PDF1 and PDF2). Several studies reported the organ-specific expression of PDF1.1 (

Yao et al. 2019). PDFs are also involved in the detoxification of heavy metals. They were entitled to this name due to their function and structural homology to that of insect and mammal defensins. These proteins are triggered by the pathogenic attack or any sort of abiotic stress, most commonly the antifungal infection (

Kovaleva et al. 2020). Different studies have reported their anti-fungal response in different plants. For example, one of the investigations has reported that PDFs of

Nicotiana alata,

Solanum lycopersicum, and

Pisum sativum induced fungal cell death by disrupting the plasma membrane which ultimately inhibited the cell division (

Sathoff et al. 2019).

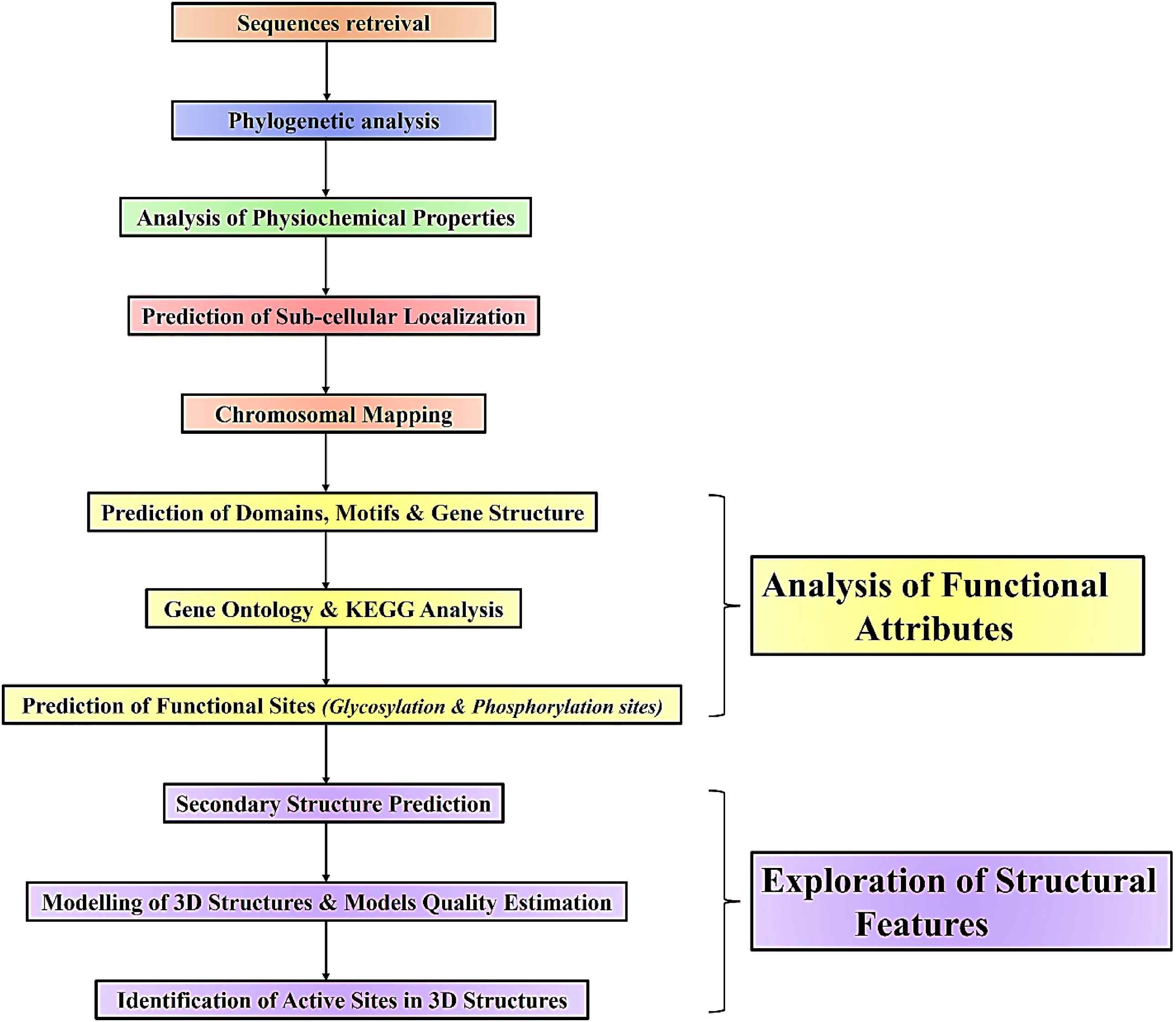

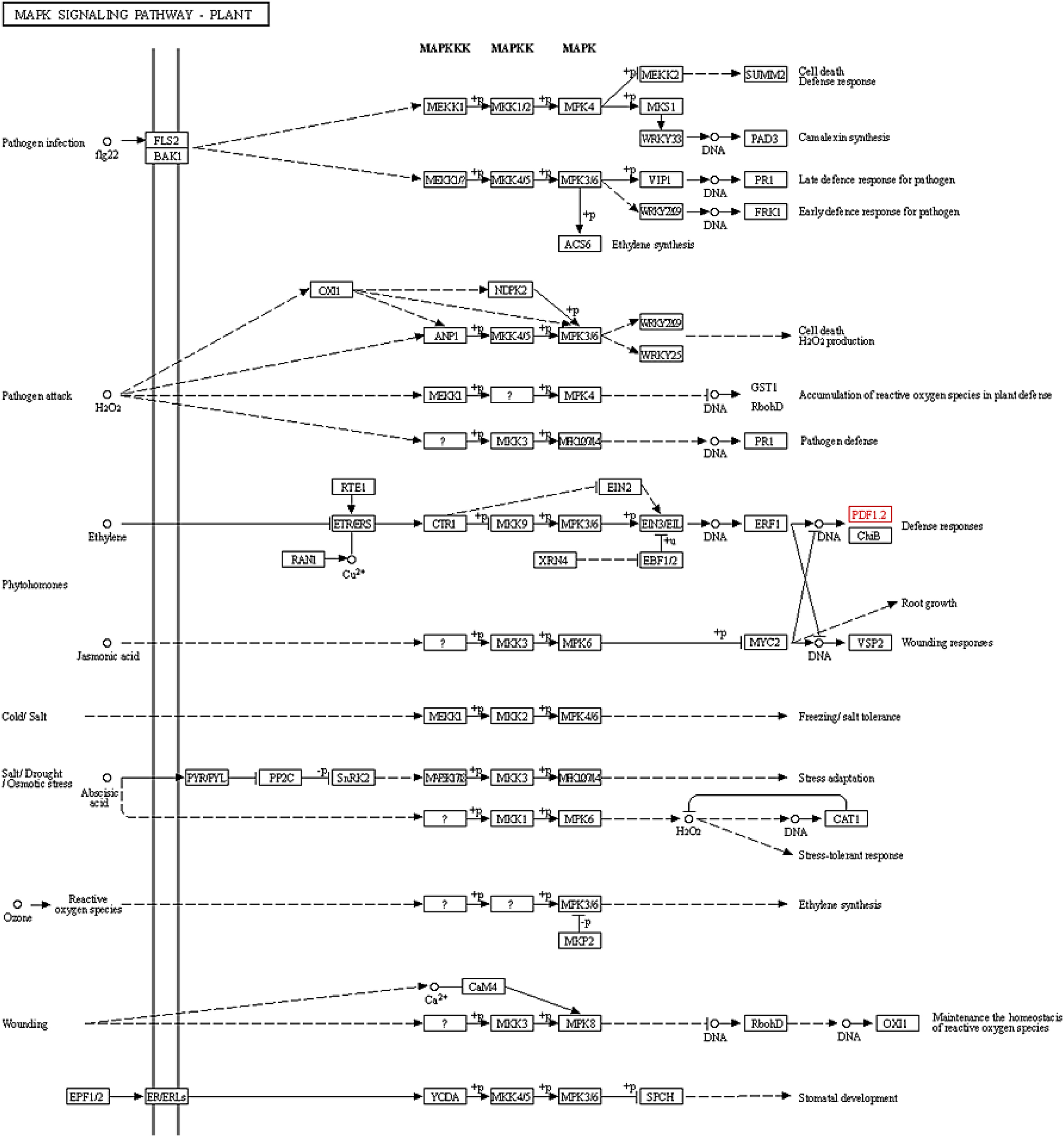

In this particular study, we have illustrated various aspects of PDF1.1 protein in B. rapa using the Bioinformatics tools, to comprehend their major characteristics. In this context, phylogenetic analysis, analysis of a conserved domain, motifs, physicochemical characterization, subcellular localization, prediction of secondary structure, and homology modeling along with exploring the pockets in respective structures were predicted. The main objective was to find the gene ontology or biological and molecular function of PDF1.1 protein in B. rapa. This study’s key findings indicate that the PDF1.1 protein in B. rapa exhibits strong antifungal activity, potentially playing a role in activating the MAPK signaling pathway to enhance the plant’s defense response against fungal pathogens. By understanding the role of PDF1.1 in plant immunity, researchers may develop strategies to induce the expression of these genes in B. rapa, providing an effective means to bolster resistance. This work offers a foundation for future efforts in breeding or engineering Brassica varieties with enhanced pathogen resilience, which could lead to more sustainable crop protection and improved yields.

4. Discussion

Turnip is also known as

B. rapa which is cultivated worldwide. It is also a medicinal plant and has lots of health benefits. Turnips are a rich source of carbohydrates, volatiles, and phenolic compounds, and have many pharmacological benefits such as antioxidant, antidiabetic, and anti-inflammation vegetables (

Paul et al. 2019). The growth of

B. rapa plant is significantly impacted by various fungal diseases, such as powdery mildew, black spots, and white rust, which collectively contribute to reduced crop yield worldwide. However, PDF1.1 proteins exhibit antifungal properties that inhibit the growth of these harmful fungal pathogens, helping to protect the plant and improve its resilience against these diseases (

Cao et al. 2021;

Mourou et al. 2023). PDFs are also found in other plants, such as

Medicago sativa (alfalfa), where they play a protective role by inhibiting crown rot disease (

Sathoff et al. 2019). Our results about the

B. rapa PDFs are that these proteins have antifungal properties and are involved in the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway.

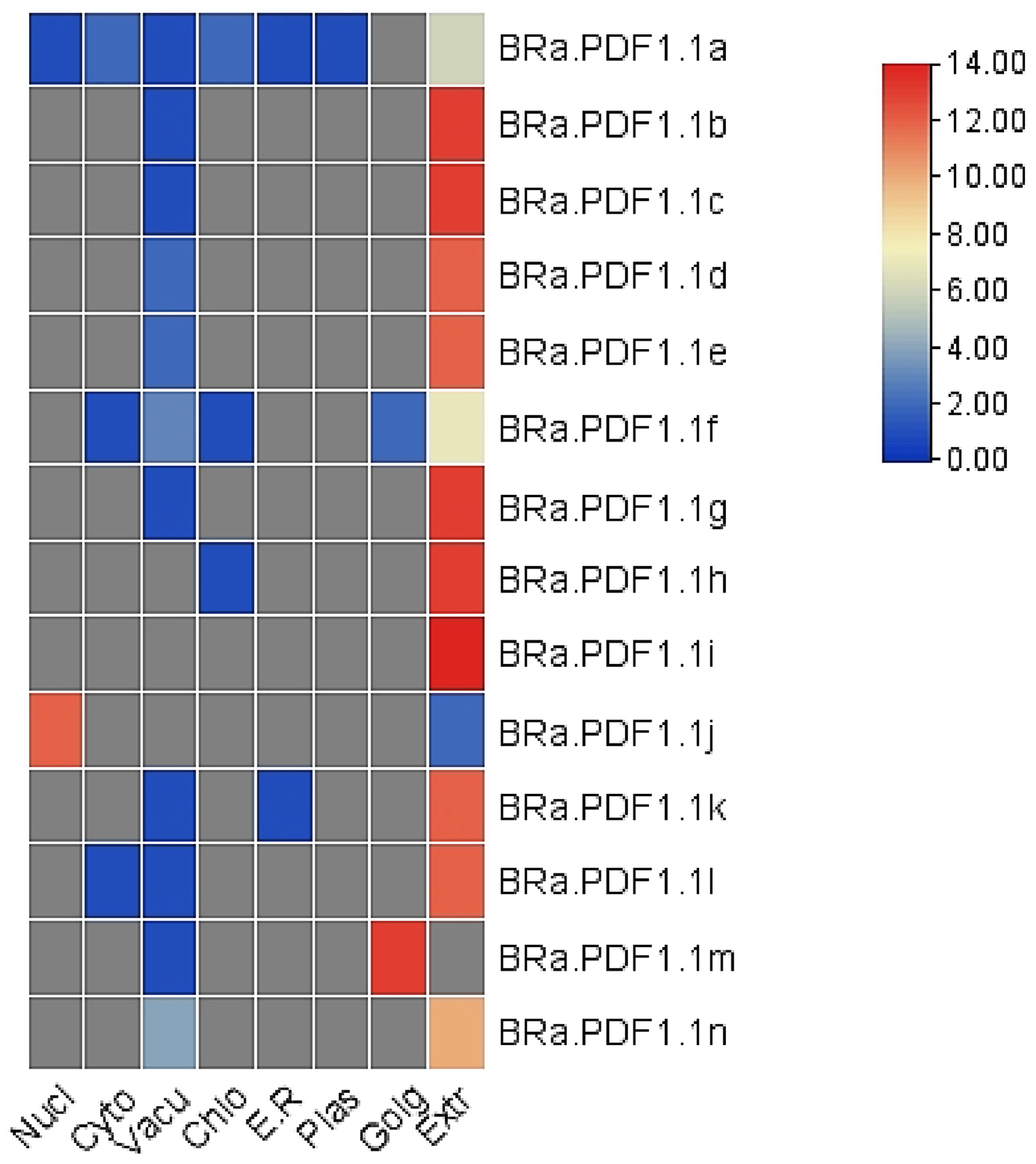

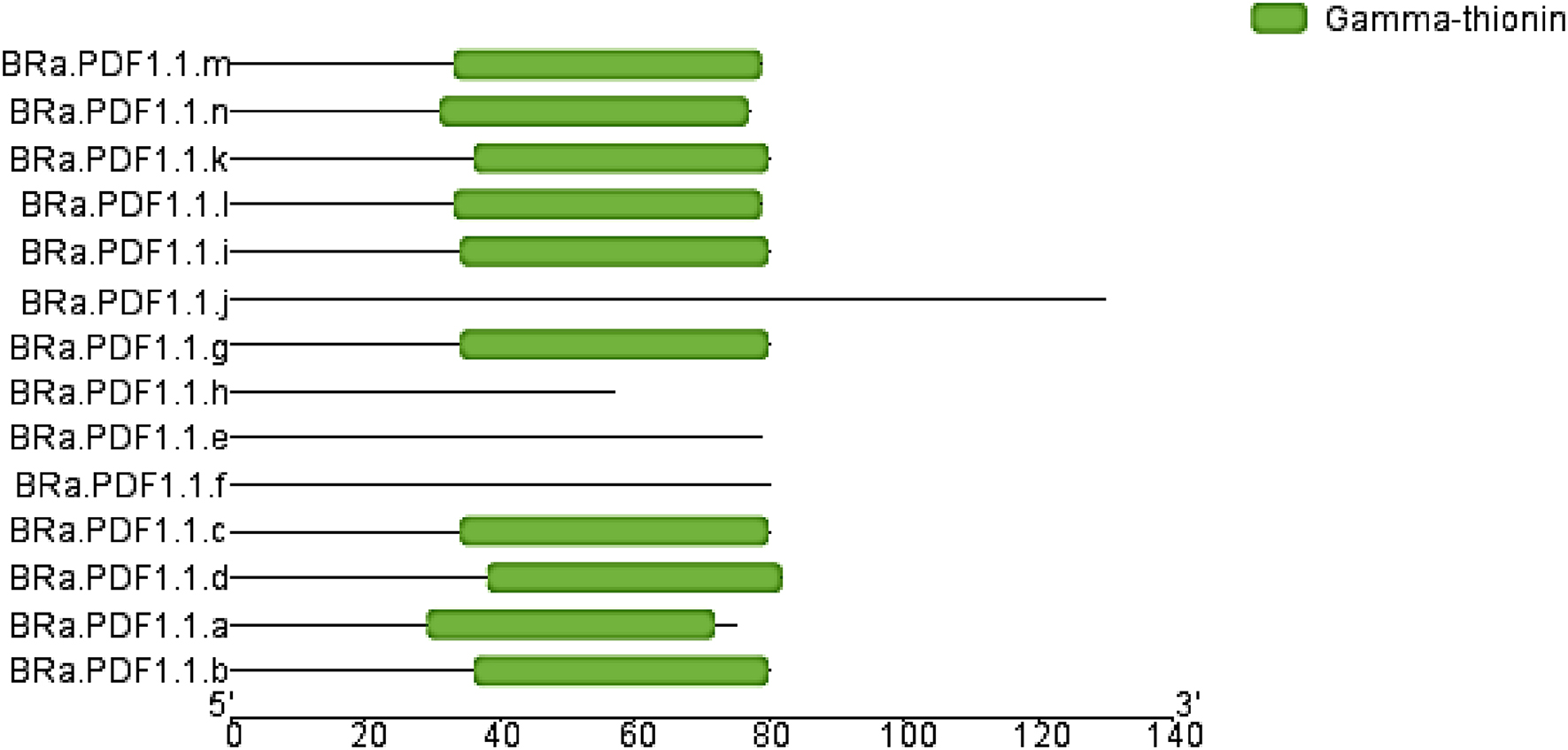

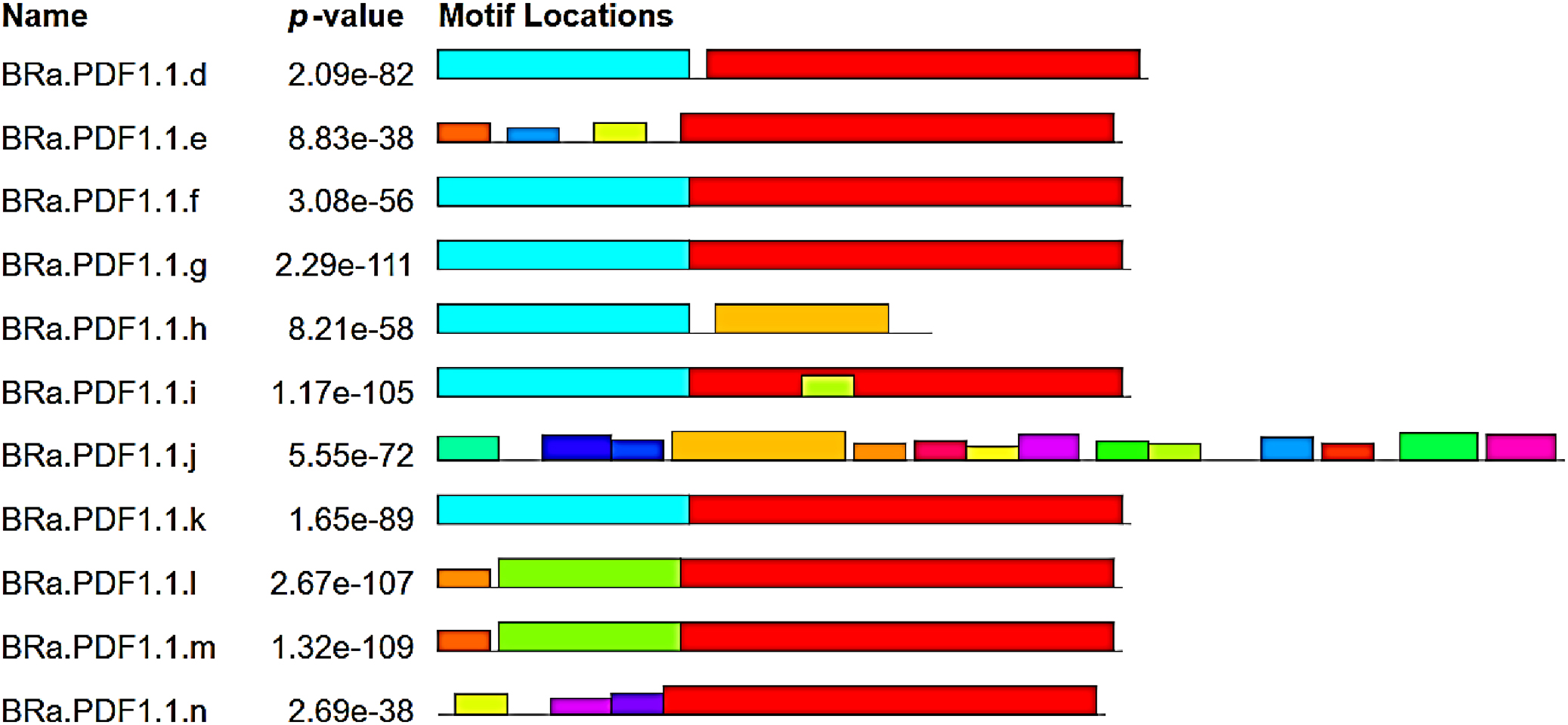

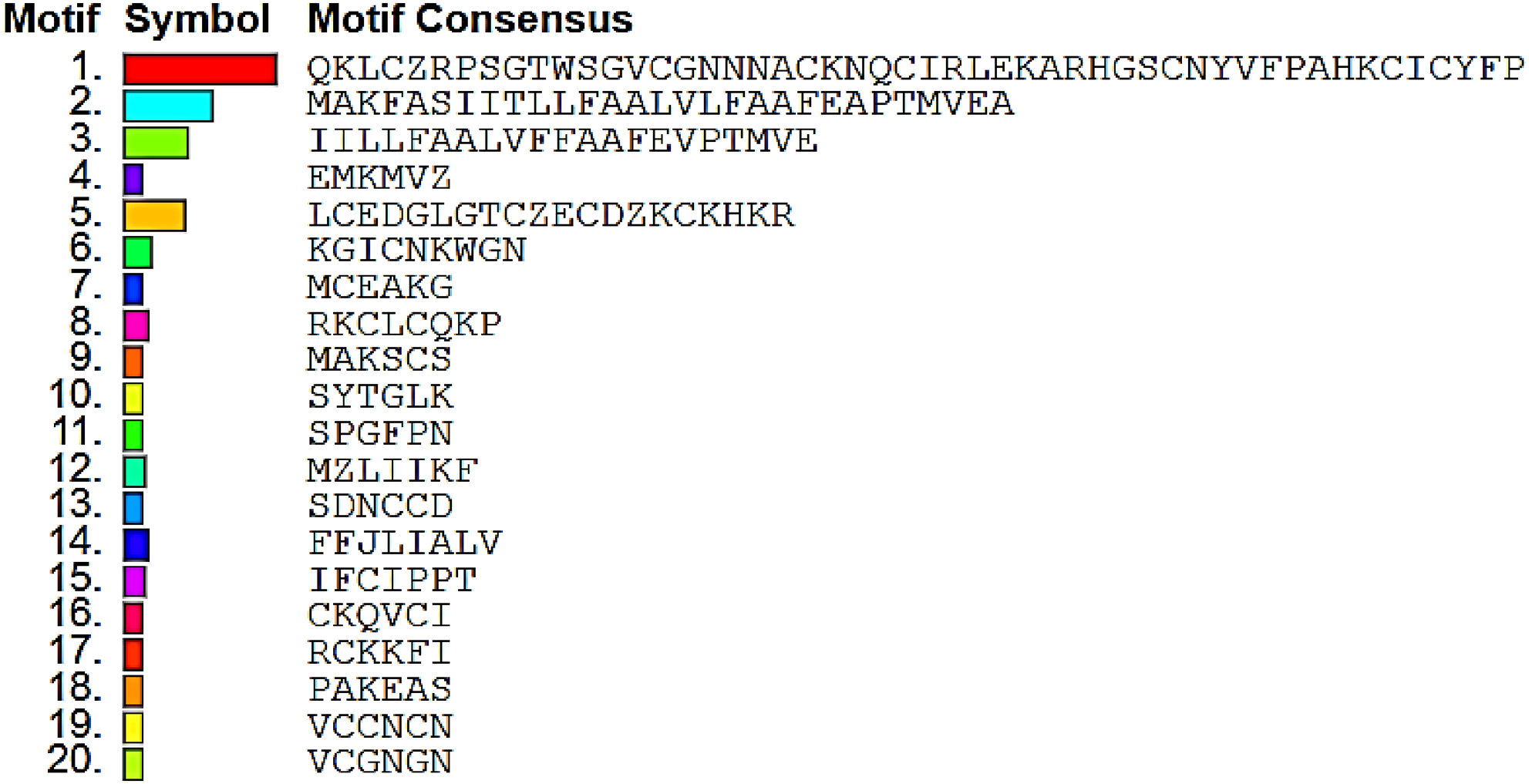

Antimicrobial proteins or peptides including defensins degrade the plasma membrane and pathogens’ cellular activities are impaired (

He et al. 2015). PDFs were first studied in wheat and barley seeds and these proteins are localized in the peripheral areas, xylem, or stomata cells (

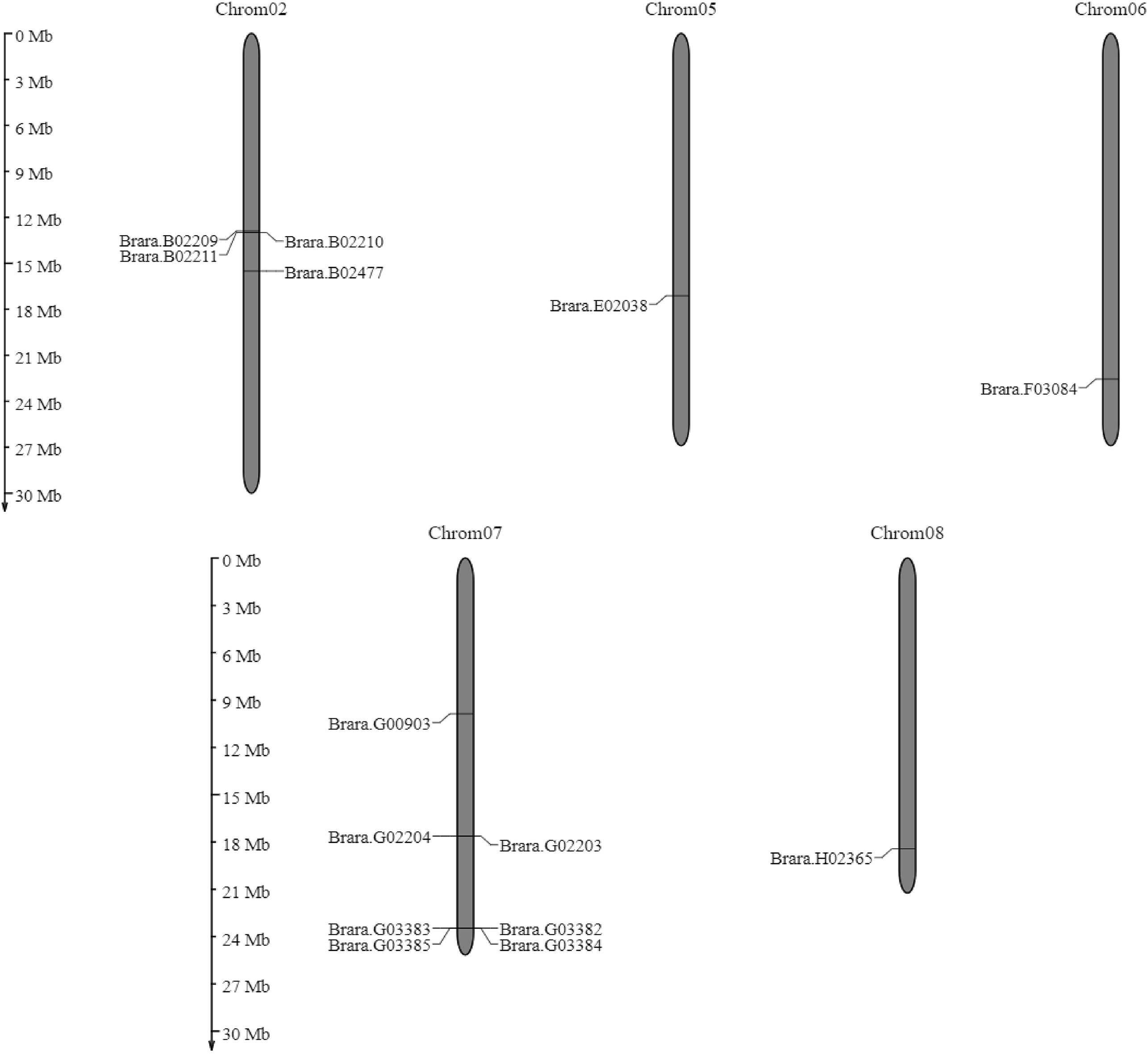

Lacerda et al. 2014). The results of this study showed that these proteins consists of the range of 57 to 130 amino acids (mostly eight cysteine residues) with molecular weights 6162.26 to 13867.87 kDa. These are the stable proteins and its isoelectric point (pI) varies from 5.05 to 9.57. Most of the

BRa.PDF1.1 genes from the 14 are located on chromosome no. 7, while some are present on chromosomes no 2, 5, 6, and 8, in

B. rapa. Fourteen BRa.PDF1.1 proteins have the same gamma-thionin domain and 20 conserved motifs were identified. We also found that these proteins are localized in extracellular space, vacuoles, nucleus, cytosol, etc. (

Zhao et al. 2022). AhDef proteins (peanut defensin) are made up of 66 to 86 amino acids with molecular weight ranging from 7.41 to 9.96 kDa and its isoelectric point (pI) varies from 6.03 to 9.77. Most of the AhDef from 12 genes are located on chromosome no 8 while some are present on chromosomes no 1, 3, 11, 16, and 18. Likewise in BRa.PDF1.1 proteins the AhDef also have a gamma-thionin domain but they have eleven conserved motifs. They also reported in their study these genes are expressed in the plasma membrane or protoplast and these proteins show resistance to

Ralstonia Solanacearum bacteria (

Vriens et al. 2014). PDFs are small peptides made up of 45 to 54 amino-acid residues and induce their response against biotic or abiotic stress as well as salicylic acid, ethylene, or methyl jasmonate.

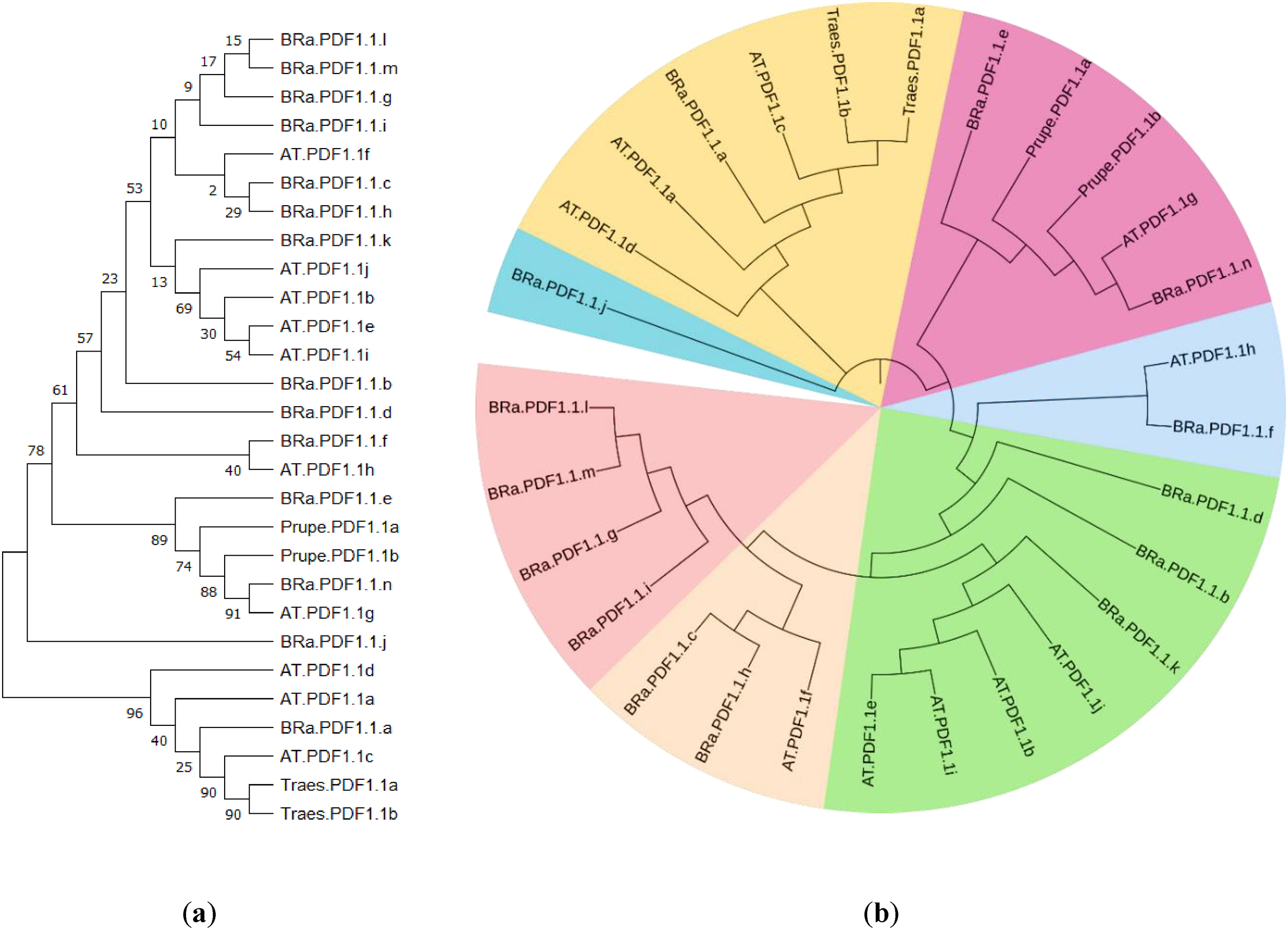

Our results regarding the phylogenetic analysis suggested that

B. rapa PDF1.1s exhibit maximum homology with

Arabidopsis thaliana but also show similarity with peach PDF1.1s in the maximum likelihood tree. The phylogenetic analysis shows that the

Brassica napus PDFs (BnaPDFs) show homology with

Arabidopsis thaliana PDFs

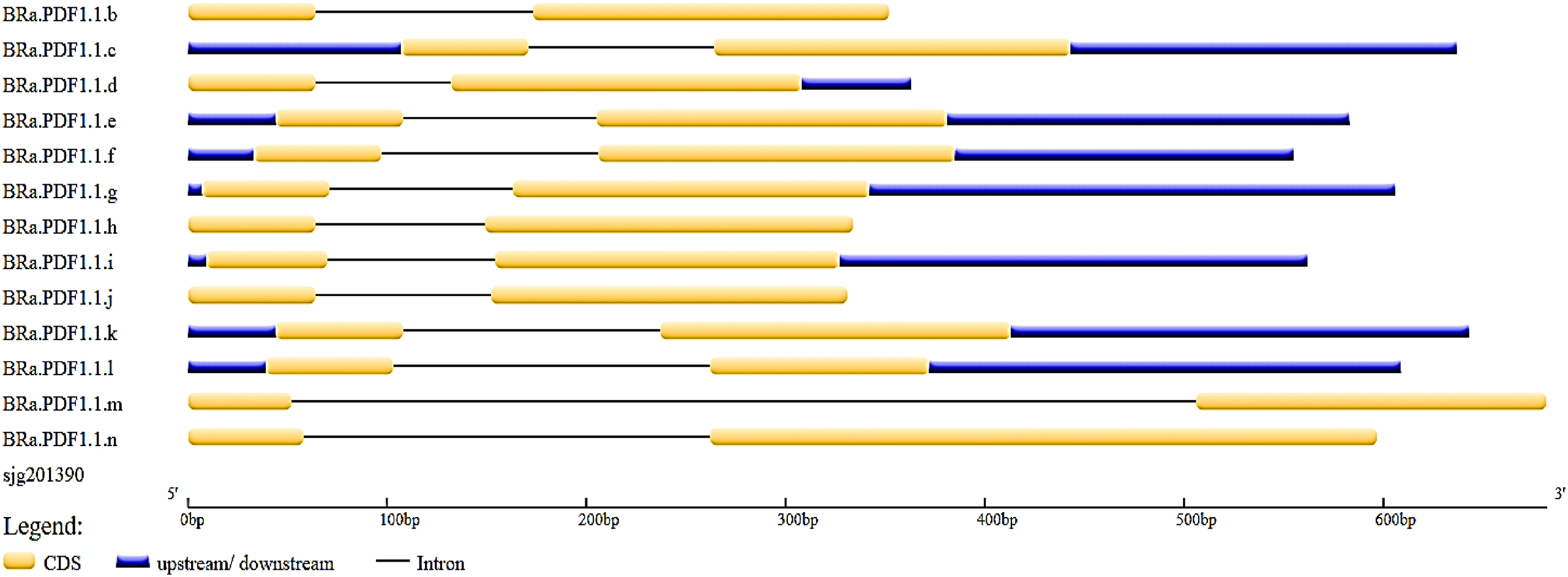

. They also found that they have alpha helix as a main component with 30% to 60%. Gene ontology (GO) of BnaPDFs and BRa.PDF1.1s was the same. The results of BnaPDFs are similar to BRa.PDF1.1s but only

BnaA5.PDF1.4 has three exons and two introns. They also report that the BnaPDFs have only one transmembrane except for one protein (BnaC1.PDF1.4). The MEGA X software has also been utilized in other studies, including one focused on generating a neighbor-joining tree to illustrate the evolutionary relationships among MYB proteins from various plants, such as

Oryza sativa,

Zea mays,

B. rapa,

Brassica napus, and

Arabidopsis thaliana (

Luo et al. 2023). The analysis conducted using the Gene Structure Display Server revealed the number and positions of introns and exons within the gene sequences. Through this tool, we discovered that all

B. rapa PDF genes contain two exons and a single intron, while

B. rapa FPsc.014 specifically exhibits longer exon regions. Additionally, this tool successfully identified the intronic and exonic sequences within

chalcone synthase genes, providing further insights into their structural composition (

Hussain 2023). Furthermore, gene ontology analysis of

Hylocereus polyrhizus using the PANNZER2 web server indicated that its main biological function is the transactivation of downstream genes (

Xiao et al. 2025).

The secondary structure analysis of BRa.PDF1.1 proteins revealed that the alpha helix was the dominant structural component, ranging from 12.00% to 82.46%. Additionally, these proteins contained smaller proportions of random coils, beta turns, and extended strands. Similarly, SOMPA was used to predict the secondary structure of the meristem defective protein in the model plant

Arabidopsis thaliana, which showed 47.20% alpha helix content (

Muccee 2024). The 3D structure predicted via the Phyre (

Paul et al. 2019) web server of PDFs has one alpha-helix and three anti-parallel beta-sheets (

Lacerda et al. 2014) which is similar to the BRa.PDF1.1s. In contrast, PDFs of

Medicago spp,

Heuchera sanguinea, and

Nicotiana alata are also involved in the MAP kinase signaling pathway (

Aerts et al. 2011;

Vriens et al. 2014;

Dracatos et al. 2016) just like the PDFs of

B. rapa. The role of the MAPK signaling pathway has been investigated in sugarcane to understand its response to pathogenic attacks, specifically by the fungus

Colletotrichum falcatum, which is the primary causative agent of red rot disease (

Gujjar et al. 2024). This disease poses a significant threat to sugarcane crops, impacting yield and quality. By examining the MAPK signaling pathway, researchers aim to uncover the molecular mechanisms involved in sugarcane’s defense against this pathogen (

Gujjar et al. 2024). Sclerotinia stem rot caused the

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum phytopathogen which affects 400 different hosts/species including the

Brassica napus (

Bolton et al. 2006). PDFs play a crucial role in a plant’s innate immune system, serving multiple protective functions. Beyond directly destroying fungal pathogens, they inhibit plant cell ion channels, block alpha-amylase and trypsin enzymes, which disrupts insect digestion, and exhibit strong antibacterial properties as well. These combined actions enhance the plant’s defense against a wide range of biotic threats.