Introduction

Since the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015), many natural sciences and engineering researchers and institutions have increased efforts to support reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. This has included, for instance, commitments by Canada's main funder of natural sciences and engineering research (

NSERC 2022), university-level strategies (

University of Toronto 2017;

University of Victoria 2017), and a growing number of collaborations between these researchers and some of the many and diverse Indigenous communities in Canada (for example,

Kobluk et al. 2021;

Codrington et al. 2022;

Yarchuk et al. 2024). Within this diversity of both Indigenous Peoples and natural sciences and engineering researchers, some may find shared values (e.g., equity, sustainability) as well as common interests in areas such as climate change, conservation, healthy housing, and ocean management (

Wong et al. 2020;

Ocean Networks Canada 2021;

IOF 2022;

Dimayuga et al. 2023;

Lyeo et al. 2024). The potential strengths from engaging with Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Western natural sciences and engineering in mutually respectful ways have been discussed in frameworks such as Two-Eyed Seeing and The Three Sisters (

Bartlett et al. 2012;

Kimmerer 2013), and have begun to be demonstrated in practice (

Reid et al. 2021).

While increased interest in reconciliation from the natural sciences and engineering is a positive trend, some Indigenous leaders have voiced concern about pressures on their communities as a growing number of researchers seek to collaborate and partner (

Canada Research Coordinating Committee 2019). In addition, research has a colonial history of exploitative practices, which has led to distrust of research among many Indigenous Peoples (

Smith 2021). The fields of natural sciences and engineering have also been responsible for the degradation of lands and cultures of Indigenous Peoples through large-scale infrastructure projects, resource extraction, and colonial land and wildlife management policies (

Cowen 2020;

Snook et al. 2020). There are still cases today where natural sciences and engineering research is carried out without appropriate respect for Indigenous rights or for the benefits brought when members of Indigenous communities lead and collaborate in research (

Wong et al. 2020). In this paper, we use the term “respectful research” to denote research practices with Indigenous Peoples that value and prioritize the experiences and perceptions of the research process by those Peoples themselves. In respectful research, partnerships are emphasized and the communities feel that the research aligns with their cultures, worldviews, and priorities (

Wilson 2008;

Dimayuga et al. 2023).

For guidance on how to carry out respectful research with Indigenous Peoples, there is a growing body of literature from Indigenous scholars. However, this is based primarily in the social and health sciences. This includes the work of

Smith (2021), who argues that Indigenous cultural values and practices must be centred in Indigenous-focused research. It also encompasses the writings of

Wilson (2008) on research as a sacred ceremonial process that understands and honours relationships and relational accountability. Relational accountability refers to care and responsibility towards research collaborators and communities, as well as to relationships with the natural world and future generations (

Wilson 2008). Research ethics protocols provide further guidance, including those of national scope (

CIHR et al. 2022), and those developed by Indigenous communities and organizations to be specific to local context and values (

Hayward et al. 2021). However,

Wong et al. (2020) argue that many natural scientists may be unaware of this guidance or fail to see the need if they are working in Indigenous territories but not directly in contact with the people who live there. The same may be argued for the field of engineering, in which students are primarily trained in technical areas often without historical context or understanding of Indigenous, cross-cultural, empathetic, or participatory approaches. Engineers Canada recently highlighted the need to create cultural safety for Indigenous students and faculty in engineering programs at Canadian universities; a field in which it is estimated that only 0.73% identify as Indigenous Peoples (

Wolf and Martinussen 2022). In addition, a recent literature review found few technical studies that reported on respectful research practices when collaborating with Indigenous Peoples, and a general lack of detail in how collaborations were carried out among those that were reported (

Dimayuga et al. 2023).

It is clear that commitment to reconciliation from researchers and institutions within the natural sciences and engineering needs to be coupled with a better understanding of equitable and respectful research processes with members of Indigenous communities. This article describes the results of qualitative interviews with members of Indigenous communities and researchers who have participated in collaborative technical research to learn from their successes, challenges, and perspectives. In the context of the diversity of Indigenous communities and their varied cultures, values, and needs, we did not aim to produce a checklist of practices for others to follow. Rather, we sought to provide considerations to stimulate thought and preparation, and examples of what it can look like and feel like to engage in collaborative technical research with Indigenous communities. We hope the findings of this work will (a) help better prepare researchers from technical fields to make initial outreach to specific Indigenous communities in informed and respectful ways; (b) provide key considerations for working in respectful ways with Indigenous Peoples; and (c) identify areas for institutional action to better support natural sciences and engineering research that is Indigenous-driven.

The need to prepare technical researchers

Throughout the interviews, the experiences and perspectives shared reinforced the need to appropriately prepare researchers from technical fields to work ethically and respectfully in support of Indigenous-driven research. All of the community members interviewed spoke of expectations that research prioritize their needs, values, and timelines. Only if this was the case, then these community members identified potential interest in research partnerships and saw a possibility to leverage research to advance community goals. These community members shared diverse details about the context of their communities, needs, and rationales for engaging in research. The needs they discussed intersected with skills of technical researchers in areas such as addressing housing decay, protecting coastal areas from erosion, and monitoring wildlife. Research could also be a tool to combat struggles to have Indigenous voices valued by decision-makers:

“When the [eulachon] collapse first started, this is one of the things that I remember hearing my dad talk about all the time, is that they were trying to go to government and say, “You need to do something about this”…The government said, “You don't have any evidence. It's all anecdotal’.” (Jennifer Walkus, Wuikinuxv First Nation)

At the same time as these expectations and potential interest from members of Indigenous communities, however, 17 researchers spoke of a lack of training and/or support in the natural sciences and engineering to facilitate respectful work with Indigenous Peoples. Some felt unsupported or alone among their peers when they attempted such projects, while others worried of harm to communities from ill-prepared researchers in a climate in which working with Indigenous Peoples was very “fundable”. Training in natural sciences and engineering programs was generally felt to focus on technical competencies and lack content available in other disciplines on Indigenous history, interdisciplinary methods, and Indigenous cultural competency. This was spoken of with particular feeling among the trainees interviewed, with eight of the 11 trainees describing activities outside of coursework to prepare themselves which, for some, was not valued by their programs:

“I had all this core material to learn…really detailed methodological things to learn and a lot of technical skills…Then there was this whole other piece that was the cultural awareness, the understanding colonial histories, the understanding the Nations where I was going to. I was kind of expected to do that in my free time and I had no free time because I was a PhD student prepping for the field…I didn't feel supported in all that extracurricular work I was doing. I wanted that to be valued as much as was learning how to code in R.” (Maryam, Non-Indigenous Researcher)

Key considerations for individual researchers and teams

The prior section speaks to the need to better prepare technical researchers to carry out Indigenous-driven research. Building on this, five key considerations are presented for individual researchers and research teams who wish to carry out such work. These are summarized in

Table 1 and are expanded upon below.

Assessing personal preparation and mindset for a community-centred approach

Thirty-nine of the 40 participants, across all groups, spoke to the importance of a mindset that centres community needs and values, and is aware of the history and ongoing impacts of colonization. Assessment of preparation and mindset should come early and may be a different starting point from the more typical technical research process of first developing ideas and then seeking funding and partnerships based on those ideas:

“If someone came and talked to me and they had the kind of background I do, no history and no contacts, I would say, stop…Don't do anything, don't write anything, don't get invested in any way until you have spoken to people about what this means and how to do it with the best standards of ethics and engagement.” (Isabel, Non-Indigenous Researcher)

Researchers described efforts to educate themselves through online courses, articles, blogs, videos, and community websites. Reflecting on what they had learned, some researchers described how the goal of this education should not be to become an expert. Instead, preparing yourself helps to reduce the burden on the community (n = 10), open the mind to other viewpoints (n = 17), and adopt an approach that is humble, prepared to listen, and be of service (n = 24). Particularly for non-Indigenous researchers, preparation can include a commitment to reflecting on and working through any discomfort encountered from working across cultures or from community member reactions to settler-scientists within the ongoing legacy of colonialism. These discussions coalesced into the notion that technical researchers should spend time in honest reflection on their position, intentions, and personal capacity before deciding to reach out to an Indigenous community for research collaboration.

Building and maintaining trust and relationships

Building and maintaining trust and relationships was discussed in depth. A key element was “starting from a place of relationship-building” whereby people and process are valued, and the relationship is prioritized over the research agenda or timeline. Among the community members this was evident in different ways, with some (n = 3) emphasizing humbleness and personal connection and others (n = 2) speaking more of a structured community process towards research relationships. For all, whether stated explicitly or implicitly, positive or negative experiences with one research group were remembered and could affect the willingness to work with other researchers in the future.

Spending time in community and on the land and helping where appropriate were consistently identified by both community members and researchers as important to building relationships, showing commitment, and letting these expand naturally around shared interests:

“You can't build relationships through emails and Zoom with community members. It's just not how you do it. By showing up physically you show that you are serious, and you care about your relationship with them.” (Kai, Indigenous Researcher)

Researchers described how initial connections may be made easier by building off the existing relationships of supervisors or colleagues (n = 17) and/or working closely with a community liaison (n = 19). The element of time flowed through discussions of relationships, with significant time spoken of as required to begin new relationships and continued time investments as important to build and maintain trust. For researchers to understand their place in community was also an important part of successful relationships. This included respecting that community priorities come before research ones and that timelines sometimes need to be adapted to events such as a death in community or to seasonal changes in community schedules. Responsibilities to community should also be honoured, and examples were given of expanding from Master's to PhD studies to allow time for community goals to be addressed, and committing to relationships for the long-term:

“Relationships with Indigenous Peoples are forever. You don't begin working with a community with the expectation that you're going to leave that community after you're done your thesis or your project.” (Léo, Non-Indigenous Researcher)

In practice, this long-term commitment may mean working with one or a few communities for an entire career or simply keeping an open line of communication past completed research and an ongoing willingness to try to meet needs as they arise.

Community-aligned benefit and action

The next key consideration is the need to centre Indigenous-driven needs and benefits within the research process. Interviews with members of Indigenous communities made it clear that research was one tool in a range of approaches to influence decision-makers and provide tangible benefits to their peoples. All of the community member participants (n = 5) spoke of how research aims should come from or adapt to benefit the community itself. This was echoed by many of the researchers (n = 26) and sets the stage for a respectful approach. This can be supported by actions to share decision-making power through such mechanisms as memorandums of understanding, advisory groups, and partnerships. As Oliver, a non-Indigenous researcher, described: “If your boss says, “I don't want you to do it this way, I want you to do it that way,” you comply. The communities are my boss.” Part of creating Indigenous-driven research was also the importance of a holistic understanding of issues in context. That is, that technical researchers cannot merely focus on technical solutions without considering a particular community's history, values and political context, as well as the larger systems context and potential impacts of technical solutions on other aspects of the community and ecosystems.

The participants also provided examples of how the process of research and its outcomes could provide tangible benefits to a community. These included, for instance, developing briefing notes for use in consultation and advocacy activities, establishing monitoring programs for wildlife and ocean patterns, leading in-school or land-based science workshops, and preserving the voices of Elders in recordings. Flowing through this discussion was the recognition that the outputs often valued by natural sciences and engineering researchers (e.g., academic publications) may be different from those valued by the Indigenous community with whom they work.

Practical and financial considerations

The fourth key consideration is a group of practical issues to think about in the planning and implementation of research for Indigenous-driven aims. Three of the five community members interviewed spoke of the need for research approval from community structures. These three noted that their communities had structures to evaluate, approve, and monitor research by external actors. This may not be the case for other Indigenous communities, as significant diversity exists in the resources and capacity available for such purposes. Robert Nelson shared details of Metlakatla First Nation's robust structure to review and evaluate external applications. He also described how it sometimes takes outsiders time to understand that his Nation is in charge of what happens on their lands and waters:

“It took a long time for them to understand…they have to make sure all the engineers, whether it's placing the rock or looking after the title mark or looking after anything, they have to make sure that Metlakatla Stewardship Society is notified.” (Robert Nelson, Metlakatla First Nation)

Other practical considerations include allowing sufficient time for a community-engaged process. For both community members and researchers this was discussed as important to relationships. However researchers, and particularly trainees, also emphasized time constraints related to program requirements and funding timelines. Questions about appropriate budgeting to support research activities were asked of researchers. Identified budget items included some that might be unfamiliar to natural sciences and engineering researchers used to lab-based or industry-partnered projects. For example, generous travel budgets to support time in potentially remote communities, food and hosting costs for community meetings, honoraria and gifting, and community capacity-building (e.g., hiring local staff, staying in local accommodations, providing equipment). Planning for appropriate data management was also raised by both community members and researchers, with particular reference to OCAP Principles (

FNIGC 2023). Discussion showed that there was not one set way to enact OCAP, and asking about and respecting wishes around how data are stored and used was considered to be most important. A final practical consideration was to build interdisciplinary teams to provide necessary insight and experience. Technical researchers described working with community members, a cultural advisor with whom that community is familiar and comfortable, advisory groups, and social scientist colleagues.

Communication and knowledge sharing

The final key consideration for individual researchers and teams was communication and knowledge sharing. On the one hand, communication is an integral piece of embedding the community in an ongoing way in the research process, and communication and knowledge sharing was discussed by four of the community members and 26 of the researchers. In addition, verifying and sharing data with the community was identified as a key activity later in the research process. Practical examples of what this meant included hosting a community gathering with food, activities, and a presentation of results. Other means of communication included newsletters, blog posts, and brief documents created with the assistance of graphic designers. Within this discussion was a sense of care with regards to community data, with links back to practical considerations around data management and respect for OCAP. At times, this means that the results of the research may be used only by the community instead of shared publicly. It is important for researchers to prepare themselves to follow a particular community's wishes regarding how results may or may not be shared instead of their own expectations for academic publication.

Effective communication to non-scientific audiences was noted by some participants as a general weakness among researchers in technical fields. This was presented as a barrier both to communicating with communities and to sharing results with decision-makers to further Indigenous-driven action-oriented goals. Science communication was pointed to as an area in which more training is needed, and one that researchers should value, budget, and plan for as part of their research activities. At a higher level still, four community members and eight researchers shared their overarching perspectives on knowledge sharing when working with Indigenous and Western scientific knowledges. This was discussed as an area in which work is still needed to ensure that the strengths of each knowledge system are equally valued. Some expressed caution around the current focus on “braiding” knowledges and pointed to the history of “cherry-picking” Indigenous Knowledges, “shoehorning” them to fit Western narratives, or “validating one against the other”.

Institutional-level factors

Earlier in this section we discussed results that spoke to the need to better prepare natural sciences and engineering researchers to carry out research for Indigenous-driven aims, followed by five key considerations for individual researchers and research teams who wish to carry out such work. In this final results section, we summarize four institutional-level factors that were identified by the participants. Depending on context and circumstances, each of these factors was spoken of as either supporting efforts towards Indigenous-driven technical research or making such efforts more difficult. This is described with respect to each of the factors below.

Mentorship

Researchers, and particularly students, who had access to strong mentorship (n = 15) identified this as crucial to learning about and facilitating respectful partnerships with Indigenous Peoples. This mentorship included that from within research institutions (e.g., Indigenous scholars, supervisors) as well as from within Indigenous communities (e.g., Elders, community partners). These mentors shared guidance, provided connections to Indigenous partners, and fostered environments that prioritized community work (e.g., routine discussion of treaty rights, support for adaptation to community needs).

On the other hand, researchers who lacked strong mentorship (n = 9) discussed this as a challenge. Some described how those they looked to for mentorship within their technical programs (e.g., supervisors) were also new to working with Indigenous communities and could not provide advice on what to read, did not have existing contacts to build from, and were unfamiliar with how to complete research ethics applications. One graduate student shared how her thesis committee had urged her to quit her studies because they felt she was not meeting her program timelines as she invested significant time and effort into relationship-building and knowledge-sharing with the Indigenous communities engaged in her research.

Institutional policies and processes

A second institutional-level factor is that of institutional policies and processes. Sometimes, these could help to create environments conducive to building and sustaining research relationships for Indigenous-driven aims. This was the case for researchers who spoke of strong ties between their academic institutions and local Indigenous communities, or who worked within clear mandates and leadership support for partnerships with Indigenous Peoples. Some researchers in government institutions spoke of how they had stable, long-term funding as well as flexible timelines. They described this as a better fit for sustaining relationships with Indigenous communities than typical one- to two-year academic timelines and funding.

However, institutional policies and processes could also present challenges. Short graduate program timelines (n = 16), particularly for Master's students, were identified as a poor fit for the time needed to build relationships and follow a flexible, Indigenous-led process. The research ethics and approval process was also discussed (n = 14), in relation to sometimes lengthy timelines for ethics approval, the importance of valuing community ethics over institutional ones, and the suggestion that ethical review should be more routine in the fields of natural sciences and engineering. In addition, financial policies around honoraria and compensation sometimes acted as obstacles to paying Indigenous collaborators in appropriate, timely, and barrier-free ways (n = 11).

Incentive and recognition structures

A third institutional-level factor was incentive and recognition structures (n = 20), which were spoken of as generally not structured to support respectful, Indigenous-driven research. Current structures were viewed as encouraging researchers to produce outputs that would advance their own careers rather than community-oriented processes and benefits:

“This whole idea of how we do science, the way the incentives are given to researchers, the system by which they're trained, the way that they progress through their careers, is not conducive to being accountable and having humility…If there's researchers out there that are just looking for their next funding and their next papers and stuff like that, we're going to have this problem all the time.” (Emma, Non-Indigenous Researcher)

Part of the issue was seen as a lack of recognition and understanding in technical fields of the time and effort that is required to carry out community-engaged work: “It's assumed that it's part of the project manager's work, but I don't think we're aware at [institution] how much time that can consume and how much time it requires to do it effectively” (Tomas, Non-Indigenous Researcher). This can lead to concerns, particularly for early researchers, about the impact on their future opportunities if carrying out research different from that typical of their fields that results in fewer academic publications.

Funding structures

The final institutional-level factor identified was funding structures (n = 30). Although researchers recognized that funding structures were changing to better support research for Indigenous-driven aims, these were still primarily presented as a challenge. Some participants (n = 9) felt that funding structures felt backwards because many do not support early conversations to identify community needs but do require detailed explanations of planned research. Others expressed that short-term funding made it difficult to support the long-term relationships that are foundational to work with Indigenous communities (n = 12), spoke of challenges with appropriately compensating for and funding the types of activities required for Indigenous-driven work (n = 11), and discussed the ability of research institutions to access and hold funding and the power this gives over research direction, process and timelines (n = 6). Even considering these challenges, researchers holding established relationships with communities showed a commitment to leveraging funding to serve the interests of those with whom they worked by, for example, writing grants knowing that project details would adapt to community interests, lengthening timelines when needed, and paying community members out-of-pocket to ensure timely and barrier-free compensation. One researcher noted that they had occasionally worked with financial administrators knowledgeable about community-engaged research and willing to advance funds to compensate community members. This suggests that building awareness about community-engaged research among financial administrators at research institutions could help to shift policies and practices to avoid the need for out-of-pocket payments by researchers.

Discussion

Overall, the results of this study align with the growing body of literature on the importance of ethical and respectful Indigenous-driven research. Researchers who wish to work with Indigenous communities should do so from a position that supports Indigenous-determined goals and respects the power of Indigenous Peoples to control what activities are carried out in their territories and with their data (

Wong et al. 2020;

Cannon et al. 2024). The power of Indigenous Peoples is particularly shown in the ways in which Indigenous organizations, leaders, and scholars are driving interest and action in key areas not only of relevance to their communities but to the broader population. This includes, for instance, the Assembly of First Nations calling attention to mold and decay in housing on First Nation reserves and Keepers of the Circle providing training pathways and partnerships for Indigenous women to help build sustainable and healthy housing (

Assembly of First Nations 2022;

Keepers of the Circle 2024). It also includes leading conservation efforts by such action as Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (

IOF 2022). Through this work, the strengths of Indigenous Knowledge Systems are evident. Indigenous Knowledge Systems upheld balanced relationships with nature for thousands of years prior to colonization and often encourage a relational approach that values responsibilities to each other, the environment, and to future generations (

Wilson 2008;

McGregor et al. 2023). Non-Indigenous researchers should be attentive to the fact that an Indigenous research agenda may not always include a role for them (

Williams et al. 2020). On the other hand, there is also the potential for collaboration between Indigenous and Western scientific knowledges to create greater understanding if this is carried out within a process that equally values both (

Bartlett et al. 2012;

Latulippe 2015).

The results of this study reinforce the need to increase efforts within the natural sciences and engineering to support research for Indigenous-driven aims. Participants identified that more researchers are taking interest in working with Indigenous communities but that they have not necessarily been trained to do this work well. Based on the experiences and perspectives shared by members of Indigenous communities and researchers who have engaged in collaborative work, we presented key considerations to stimulate thought and preparation among others planning and carrying out such endeavours. While these considerations were discussed by both community members and researchers, we found the emphasis within them sometimes differed between these two groups. The interviews with Indigenous community members were each set within the significant detail and context they shared about their specific communities. Despite evident diversity in locations, needs, cultures, and resources between their communities, through all of their discussions was an emphasis on action and advocacy to advance community priorities. For the Indigenous community members, this emphasis on action flowed through all the other themes from preparation and expectations for researchers, to community-aligned benefits of projects, to effective knowledge sharing. While working for community benefit was also raised by all the researchers interviewed, all but four were non-Indigenous researchers and the majority of the discussions were less personal and political in terms of motivations for research. For researchers, cutting across all the other themes was a sense of struggle against the established processes of their institutional systems as they attempted to carry out research for Indigenous-driven aims. Researchers who were more experienced or trainees with strong mentorship seemed to have more positive experiences than those who were newer to the field and/or lacked such mentorship.

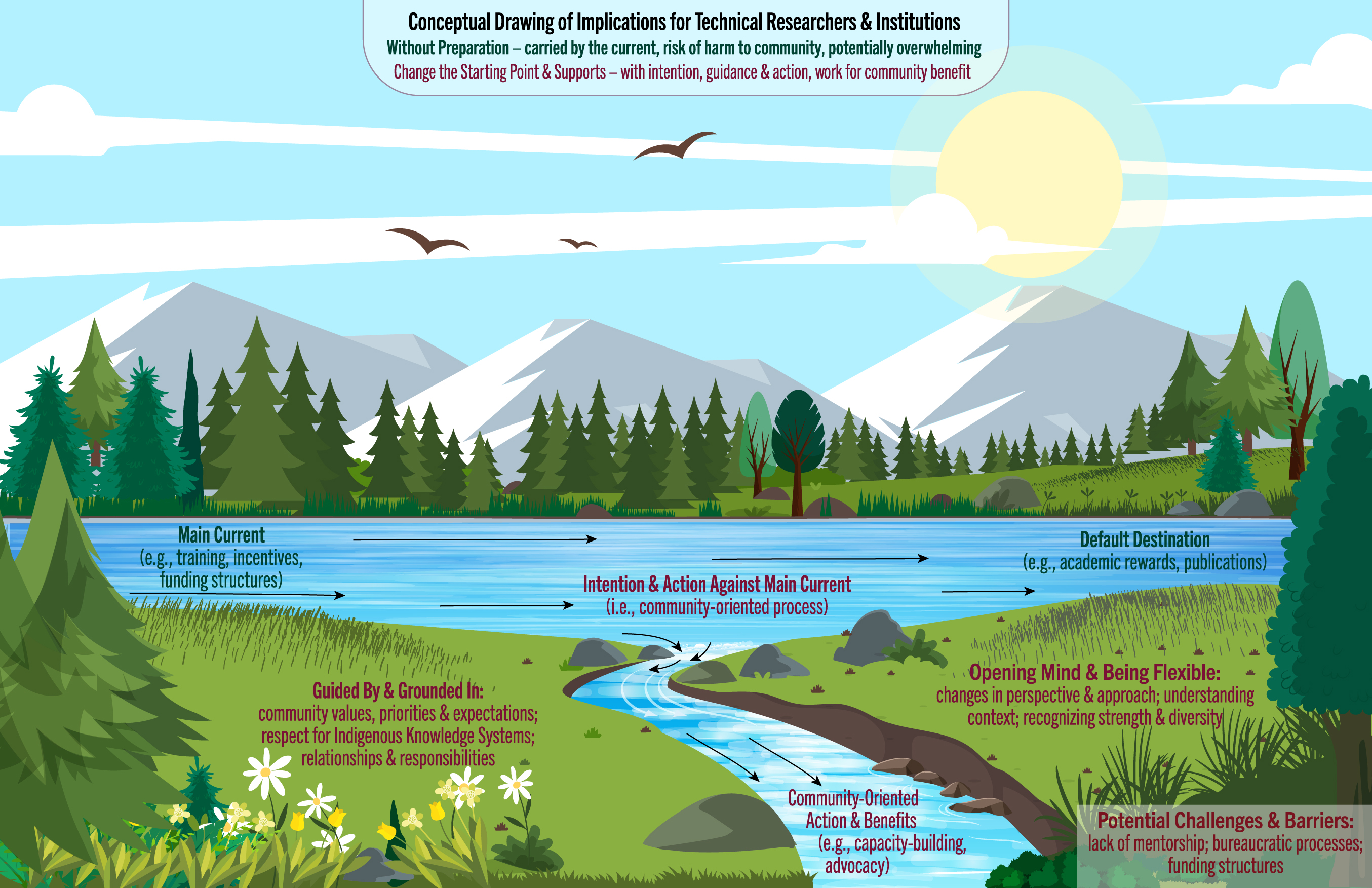

In all, the lessons learned from this project show a need to re-frame the starting point in the research process away from specific project design to assessing personal preparation and mindset to support Indigenous-driven technical research. They also point to factors of the institutional environment that can help to facilitate or hinder respectful research for Indigenous-driven aims. In

Fig. 1, we share a conceptual drawing to represent the high-level implications of these results for researchers and their institutions. The forces at play driving the direction and focus of technical researchers may be viewed as the currents in a strong river flowing towards its main destination. These currents are the training programs, funding, and reward structures that incentivize natural sciences and engineering researchers to work within relatively short timelines and to produce academic outputs of benefit to their careers. A deeper consideration of the river and its roots leads one to understand where it flows from (e.g., colonial institutions), and the push of its main current (i.e., Western science-centred power).

At the same time, some researchers and partners work against the main current of the river towards an alternative route (an Indigenous community-oriented and community need-based process). This route requires a different starting point. Rather than jumping straight in, it takes deliberate action and significant effort and commitment, as its destination (community-oriented benefits) is not primarily supported by the main current in technical fields. It also requires guides who are familiar with this route and understand how to travel it (e.g., community partners, Indigenous advisors, mentors). Along the way, if they listen and remain open and flexible, researchers will come to see and understand strength, diversity, and connectedness (i.e., Indigenous worldviews, diversity, and action). However, it is also a rockier route with potential barriers along the way (e.g., bureaucratic processes). Without adequate preparation, even with the best intentions, researchers may be carried by the main currents to more typical academic outcomes or feel overwhelmed by the process. With the appropriate preparation, however, technical researchers may successfully contribute to Indigenous-driven aims and reconciliation.

Recommendations

Further to this conceptual understanding and grounded in the findings of this research, we recommend six actions for research and research funding institutions to help foster environments supportive of respectful research with Indigenous Peoples. While the majority of the results earlier in this article speak to actions that individual researchers and students can take to support Indigenous-driven research, the recommendations in this section focus on the need for structural change within the institutions these researchers work. Such institutions are not limited to academia but may include those in the public and non-profit sectors as well. The specific recommendations we provide are set within a broader need for the decolonization of research and research funding institutions to support Indigenous self-determination. Decolonization is a term that may be used in different ways by different authors (

Cicek et al. 2023). In this article, we understand decolonizing efforts as seeking to make space for Indigenous and international cultures by working to remove bias and hierarchies that privilege Western approaches (

Wolf et al. 2022;

Hill et al. 2023). In light of this, decolonizing institutions and training programs may be considered as groundwork to create mindsets and spaces for undertaking collaborative approaches, such as Two-Eyed Seeing, that promote respectful work across both Indigenous and Western scientific worldviews. While some institutions have taken steps towards decolonization (

University of Toronto 2017;

University of Victoria 2017;

Canada Research Coordinating Committee 2019), continued and concerted effort is required to ensure the implementation of strategic plans and progress towards stated goals. The recommendations that we provide from this research work in support of decolonization of research institutions, are listed in

Table 2, and are discussed in more detail below.

The first of these recommendations is for research and research funding institutions to mandate Indigenous cultural competency training for all staff at all levels. Cultural competency training should aim to counter tendencies to overlook or homogenize the diversity of Indigenous Peoples and to create understanding of the importance of informing oneself about the particular place-based governing systems, protocols, and values of potential Indigenous partners. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Call to Action number 62 focuses on the need to embed Indigenous contributions and Knowledges into how we teach Canada's youngest students. The need for education and training to support reconciliation is further emphasized with respect to the corporate sector in Call to Action 92 (

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015). These Calls to Action recognize the broad educational gaps that exist in Canadian society on understanding Indigenous history and worldviews. While examples of cultural competency training do exist at research institutions (

University of Toronto 2021;

Memorial University of Newfoundland 2024), these are often optional programs rather than mandatory ones.

Further to the first recommendation, as a second, we also suggest training and mentorship for technical researchers in Indigenous studies, community-engaged methods, and approaches that understand technical solutions within larger contexts (e.g., systems approaches, empathetic design). This specifically seeks to address the training limitations in natural sciences and engineering fields identified by the participants as well as siloing between disciplines. To support efforts to add Indigenous context and increased self-reflection in technical training, it is possible to draw on an emerging body of resources on how to decolonize scientific institutions and the curriculum of fields such as engineering (

Wolf et al. 2022;

Cicek et al. 2023). For fields such as the natural sciences and engineering, this includes critical reflection on power relations within research institutions and on the power given to Western science to create evidence about our world (

Hill et al. 2023).

Our third recommendation is to adapt incentive and recognition systems to value all stages of community-oriented research and outputs identified as valuable by communities themselves. These may include outputs not traditionally valued by research institutions to support community interests or respond to requests on the community (e.g., as part of government consultation and impact assessment processes). This involves a change in understanding of what is deemed to be a success by academic standards and how the performance of researchers is evaluated. For many researchers in the natural sciences and engineering, career progression may still be evaluated with academic publications as a primary indicator of success. This overlooks the significant time and effort community-engaged researchers put into such activities as relationship-building, establishing Memorandums of Understanding, and creating knowledge products of value to their Indigenous partners. One piece of changing the predominant paradigm of success is for researchers, within both academic and government institutions, to have dedicated and valued time in workplans for relationship-building and maintenance.

Fourthly, we recommend an increase in funding opportunities for technical research collaborations with Indigenous communities, particularly for funding held by Indigenous organizations and communities where the capacity exists to do so. Holding funding confers greater power over decision-making and the direction of research.

Williams et al. (2020) argue for Indigenous research sovereignty, and that the current research governance approach enacted by Canada's main federal research funding agencies does not do enough to counter historic injustice towards Indigenous Peoples and support their research goals. At the same time, the resources and capacities of Indigenous communities vary greatly and, for some, holding research funding has the potential to create administrative burden. Investments in Indigenous community-based research administration capacity is needed from Canada's federal research funders (

Williams et al. 2020). Strategic partnerships between communities may also allow resources to be pooled, while individual researchers may contribute to capacity-building by hiring local community members to help with project administration, providing training to community members as part of projects, and offering their skills to support Indigenous partners in setting up research administration processes. Participants in this current study also spoke of the need for more long-term funding opportunities to account for the significant time investment that is required to build relationships and honour commitments to Indigenous communities.

As a fifth recommendation, we point to the need for mechanisms within technical research institutions to support sustained, long-term connections with local Indigenous communities. Such mechanisms may help to guide technical researchers who are less familiar with relationship-building processes and sustain relationships beyond single individuals. It may also make it easier to introduce researchers with tighter timelines (e.g., graduate students) into pre-existing collaborations in respectful ways. Examples of potential mechanisms may include permanent staff and dedicated offices within research institutions to engage in ongoing and non-project focused ways with local Indigenous communities, and to manage and provide advice to researchers within organizations. Demonstrated commitment to partnerships with local Indigenous communities by senior administration may also lay the foundation for relationships with researchers and teams, including supporting Elders and Knowledge Keepers to have roles in governance structures, participating in local community events where appropriate, and inviting feedback and open communication regarding the activities and directions of research institutions.

The final recommendation works in support of all the prior recommendations. While the intent is not to place the burden of reconciliation efforts on Indigenous Peoples themselves, increasing representation of Indigenous Peoples within research and funding institutions may go hand in hand with broader structural efforts to decolonize these institutions, support Indigenous-led research, and integrate Indigenous ways of knowing and doing into education and research processes. Indigenous Peoples are currently underrepresented among those holding science, technology, engineering, or mathematics degrees more broadly as well as within the profession of engineering (

Wong et al. 2020;

Wolf and Martinussen 2022). Examples of strategies to improve the recruitment and retention of postsecondary faculty and students include meaningfully incorporating Indigenous cultural supports on university campuses (e.g., Elders in residence, Indigenous cultural centres), implementing equity-based hiring processes including for senior administrative positions, providing, and supporting Indigenous mentors for new hires and students, targeted outreach and financial support for Indigenous students, and flexible learning options to allow students to remain connected to their home communities (

Pidgeon 2016;

University of Victoria 2017;

King and Brigham 2022).