Science and engineering aim to solve some of the most challenging problems faced by humanity, as well as fundamental questions about our universe and its most elementary constituents. From climate change to disease, designing better homes to curing cancer, science plays a central role in understanding our existence and improving our lives. However, for scientific fields to tackle the most profound challenges, we need to address the longstanding challenges to equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics; science and STEM are used interchangeably in this article). On this basis, full equity and representation in STEM were proposed as the primary science “moonshot” of our time (

Graves et al. 2022). The “moonshot” terminology conveys the idea of a monumental challenge that may be achieved with the right mindset, which combines courageous effort, audacious belief, and collective action. Graves et al. argued that the “STEM equity moonshot” is the

primary moonshot because it is foundational to achieving other science-society challenges.

The challenges to EDI in STEM affect

who engages in STEM and their experiences, as well as

how STEM activities occur, their success, and their applicability to society (

Gvozdanovic et al. 2018;

Kearney et al. 2021;

Kozlowski et al. 2022;

Thomson 2022;

Council of Canadian Academies 2024). This article considers “EDI” in a broad way, aligning with the Dimensions Charter (

Government of Canada 2019) and recent Council of Canadian Academies report (

Council of Canadian Academies 2024).

Equity is a principle that relates to fairness, with individuals of all identities, characteristics, and backgrounds being treated fairly and respectfully, considering, for example, opportunities, access, treatment, power, outcomes, and resources, while recognizing historical and systemic barriers.

Diversity relates to heterogeneity or differences within a group, often considered in terms of race, ethnicity, gender identity or expression, family status, disability status, sexual orientation, age, socioeconomic situation; diversity recognizes that an individual’s combination of characteristics and intersecting identities contribute to their experiences.

Inclusion can be considered an ongoing process of intentionally creating welcoming and respectful environments and systems in which inequities in power and privilege are addressed, and where there are opportunities for everyone for flourish. At the individual level, inclusion refers to a sense of belonging and feeling valued, supported, and respected (

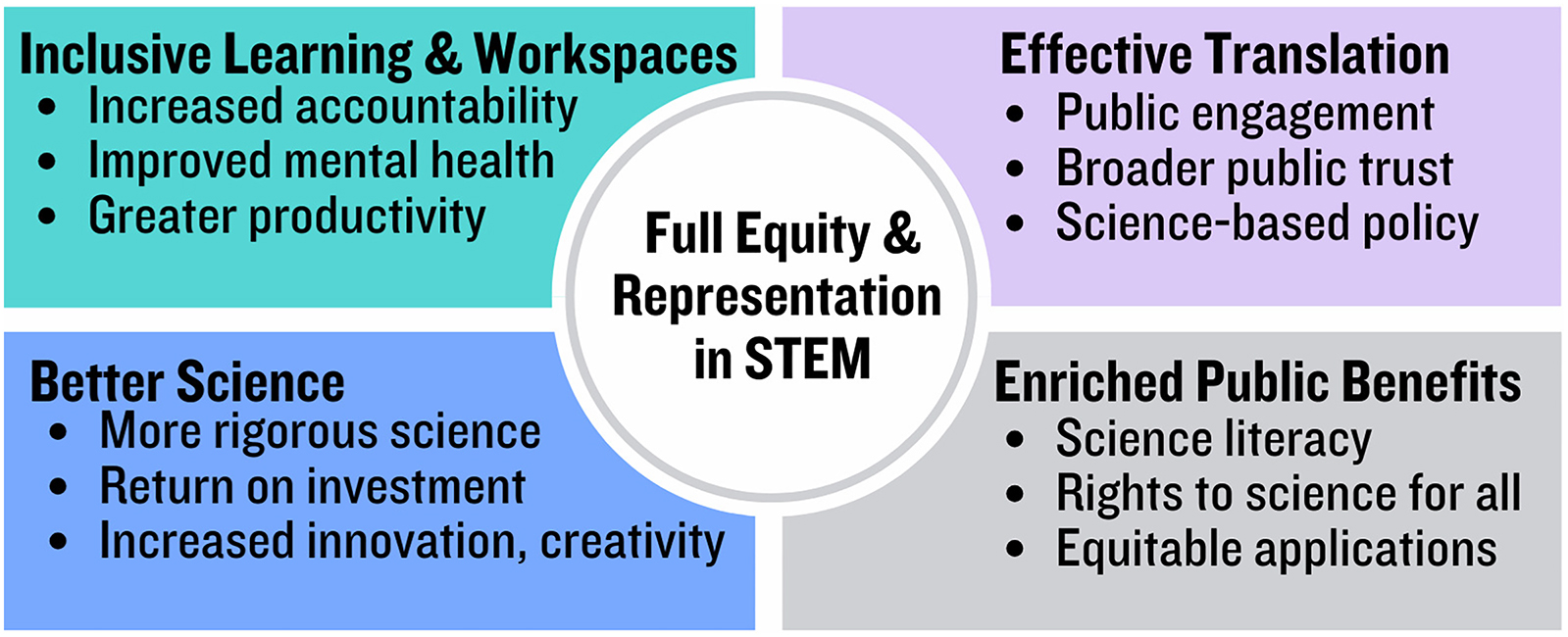

Council of Canadian Academies 2024). The benefits of EDI in STEM institutions and society are profound, spanning the realization of human rights, improved learning and workspaces, and better science that reflects social needs and priorities across societal groups (

Kearney et al. 2021;

Kozlowski et al. 2022) (

Fig. 1). Finally, integration of EDI throughout STEM research and development has been shown to lead to better science and engineering (

Nielsen et al. 2017;

Fine and Sojo 2019;

Tannenbaum et al. 2019;

Hunt et al. 2022;

Phuong et al. 2022).

The importance of full equity and representation in STEM cannot be overstated and many scientists and engineers are motivated to effect change; however, they may lack the knowledge and skills to do so, or feel overwhelmed and unprepared (

Prochaska et al. 2006;

Coe et al. 2019;

Graves et al. 2022;

Dancy and Hodari 2023). With this in mind, we developed resources that we hope will empower scientists and engineers to support widespread change. Advancing EDI is a journey, and concrete actions—small and large—will contribute to meaningful change. Advancing EDI is also an innovation challenge (

Kang and Kaplan 2019) that can be tackled in ways that are familiar to scientists and engineers: for example, experimenting with new methodologies, collecting data, adjusting tactics, and learning from mistakes and triumphs.

Aligning with the spirit of EDI advancement as both an ongoing journey and an innovation challenge, we have developed two resources for the scientific community: (1) an EDI “Toolkit” for teaching (

Harris et al. 2024b) (

Fig. 2); and (2) an EDI “Pocket Guide” for research (

Harris et al. 2024a) (

Fig. 3). These resources are not meant to be read from end-to-end nor implemented all at once; rather, they aim to inspire actions at different points along these journeys by providing specific strategies, ideas, activities, and practical tools for integrating EDI into STEM teaching and research. Neither document is intended to be an exhaustive resource, but rather a starting point to stimulate reflection, spark thoughtful conversations, and inspire action. Ideally, these resources will be adopted across departments or faculties, as the work of transforming teaching is most effective when adopted collectively (

Wieman et al. 2010) and when faculty are supported by their peers (

Bathgate et al. 2019). The present

Perspective article provides an overview of the Teaching Toolkit and Research Pocket Guide, as well as details for how to access and adapt both resources. We hope that sharing these documents widely will lead to adoption of actions that advance EDI in STEM, inspire further growth, and lead to meaningful change in the inclusive culture of our institutions and fields of study.

Teaching toolkit: “Science is for everyone: Integrating equity, diversity, and inclusion in teaching science and engineering—a toolkit for instructors”

Inclusive teaching is about fostering inclusive classroom environments and engaging in practices that support learning across diverse student populations in our courses.

Dewsbury and Brame (2019) describe the development of an inclusive teaching practice as a

process that requires instructors to engage in deep reflection about their teaching, a process that parallels instructors’ expectations for learners to reflect on their learning (

Dewsbury and Brame 2019). We propose that this reflection happens in concert with concrete steps that build upon each other to propel a deeper understanding and transformation of teaching practices.

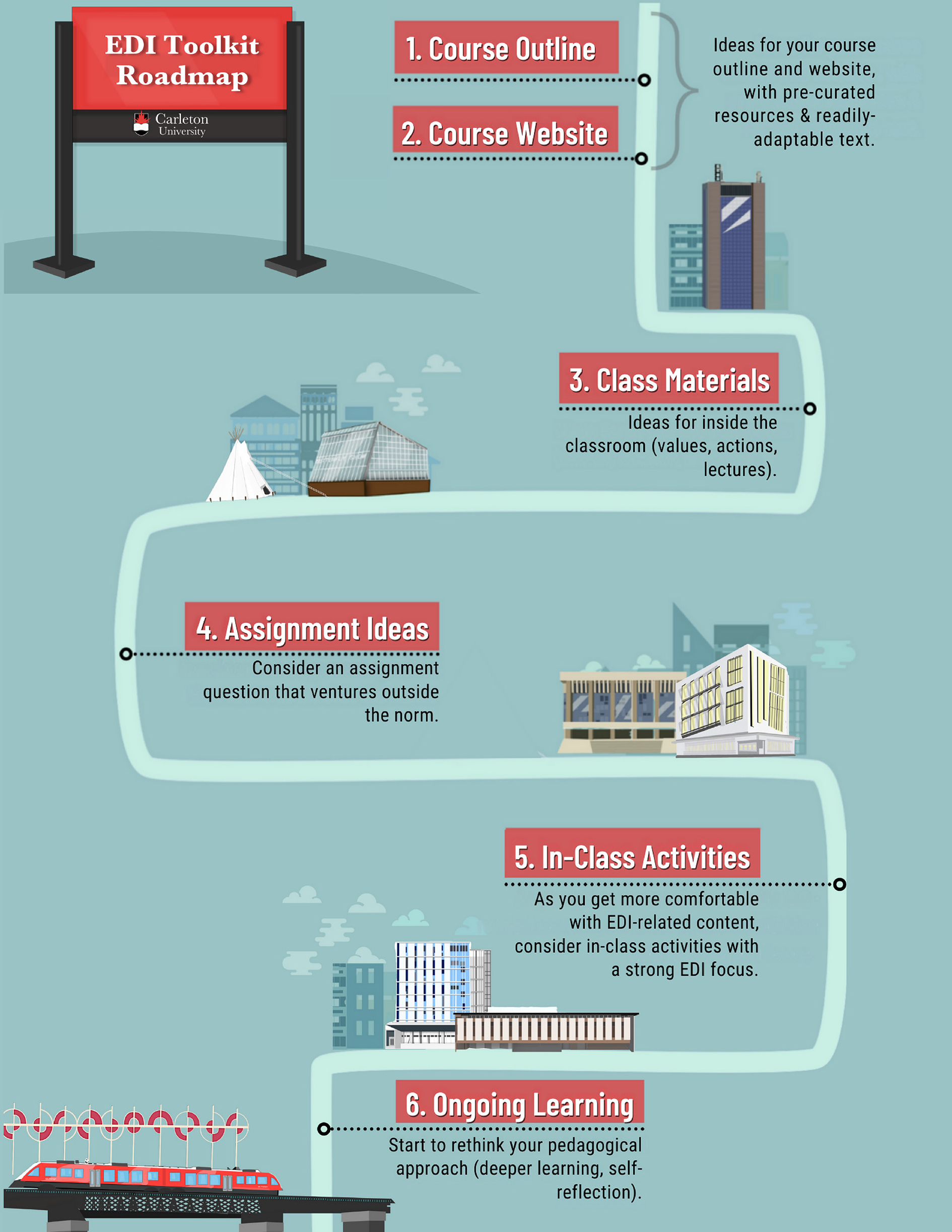

Crafted with instructors in mind, the Teaching Toolkit offers actions, activities, and tools specifically designed to assist those who are not experts in EDI. Its unique structure operates as a journey, encouraging users to engage with its contents progressively, as shown in the table of contents “roadmap” (

Fig. 4). The toolkit presents concrete ideas that are straightforward for an instructor to implement in their course.

The toolkit is divided into six sections, each addressing different aspects of course design and the delivery process (

Fig. 4). In every section of the toolkit, there are “Have you considered?” bullets that provide ideas on ways to promote inclusive learning environments. Examples include using multiple modes of expression for assignments, multiple assessment components, and sharing rubrics and assessment criteria with students. These suggestions align with recent research findings demonstrating that increased course structure and active learning approaches reduce failure rates in undergraduate STEM courses (

Freeman et al. 2014) and disproportionately benefit historically underrepresented students (

Haak et al. 2011;

Eddy and Hogan 2014;

Theobald et al. 2020). The suggestions also incorporate Universal Design for Learning principles, such as multiple modes of expression and providing students with options and flexibility, an approach to teaching that advances equity for all students (

Fritzgerald 2020;

Novak and Chardin 2021).

The first two sections of the Teaching Toolkit offer suggestions for a course outline and course website inside a learning management system. These suggestions range from example text that can be used in a land acknowledgement, to community guidelines (with an example code of conduct), to institutional mental health resources, and course syllabus template. The course syllabus template is embedded with inclusive teaching practices and the annotated template includes notes that briefly describe those practices. For example, it prompts instructors to include specific course design features such as distributed practice, low and medium-stake assessments, and active learning, all of which have been identified as inclusive teaching practices (

York et al. 2024). Informally, the colleagues on our campus who have used the teaching toolkit specifically mention the utility of the syllabus template as an easy way to prepare their syllabi while compelling reflection on their teaching practices. Most of these suggestions are small actions that instructors can easily incorporate (e.g., include land acknowledgment in a course, or explicitly state how instructors would like to be addressed) or tools that they can use (e.g., NameCoach (

https://cloud.name-coach.com) to help with pronunciations, or links to institutional supports for mental health). The goal is to provide instructors with small actions that, as an aggregate, can make their courses more inclusive and make a difference to students. No list of inclusive teaching practices is exhaustive; instead they are concrete measures that instructors can take to explicitly address equity with conscious course design (

Tanner 2013). For a more comprehensive approach, readers will be interested in the work of Artze-Vega and colleagues who have written the

Norton Guide to Equity-Minded Teaching (

Artze-Vega et al. 2023).

The third section of the Teaching Toolkit, “In the Classroom”, focusses on actions, values, and course material that can be implemented to improve the classroom environment. These range from suggestions of using non-gendered terms (e.g., “folks”), incorporating examples of scientists from different backgrounds, and including Indigenous Knowledge in an ethical and authentic way (

Steele et al. 2020). The “Have you considered?” subsection invites the instructor to reflect on specific classroom approaches (including Universal Design for Learning (

Fritzgerald 2020;

Novak and Chardin 2021)), the role that the hidden curriculum can play (

Hariharan 2019;

Balls-Berry et al. 2024), and consider accessibility in lab and field work.

The fourth section, “Assignment Ideas”, proposes a range of creative assignments designed to extend students’ skills beyond the content mastery and quantitative skills that are often emphasized in STEM courses. These assignments—like “Science Hero” and “Debunking Fake News”—foster the development of communication and knowledge translation skills, as well as different ways of thinking. They also offer opportunities for students to develop their identity as a scientist, which contributes to student retention, particularly for individuals from under-represented groups (

Kalender et al. 2019). Each assignment is accompanied by explanations on how they promote EDI, with example assignment templates and rubrics.

As an example of an Assignment Idea, the “Science Hero” activity challenges students to select an inspirational figure relevant to the course. Students are asked to describe the individual’s contributions to their field and articulate their personal rationale for “hero” status. This integrative learning activity helps students create connections between personal, academic, and professional experiences; it acknowledges the potential for affective learning (i.e., involving emotion) in developing motivation, inspiration, and engagement alongside traditional knowledge and skills (

Rowat 2005). Our experience (from teaching a physics course (

Thomson et al. 2019)) is that the activity inspires student excitement as they learn about the course topic in a self-directed way while also making a connection to the person behind the scientific contributions. Themes that have emerged from student responses to this non-traditional assignment include passion for research, importance of knowledge translation, persistence in the face of adversity, contributions to training and mentorship, and valuing diversity. We have also observed that this creative activity supports student engagement, positive classroom cultural values, and development of a physics identity (

Rowat 2005;

Albanna et al. 2013;

Kalender et al. 2019), and addresses the often-overlooked learning outcome of considering physics in its historical, professional, and Canadian context.

The fifth section, “In-Class Activities”, introduces pre-designed EDI-focused activities that are engaging and easy to integrate into class time. These activities cover topics such as impostor syndrome and unconscious bias, and include optional discussion prompts and interactive elements. The goal of these mini-lessons is to raise individual awareness of the sometimes-invisible barriers, and thereby further equip students with tools to recognize these challenges.

The final section, titled “Ongoing Learning”, is a curated selection of resources for those committed to deepening their understanding of EDI. The resources provided here range from short articles and infographics to more extensive materials like journal articles, external toolkits, and podcasts. This section is designed to drive deeper learning and self-reflection for those looking to expand integration of EDI into their teaching.

The overarching goal of the Teaching Toolkit is to simplify the adoption of EDI in STEM education. It aims to provide practical, effective tools for educators to start or continue their journey of integrating EDI in teaching. It also emphasizes the role educators play in shaping students’ experiences and perspectives, highlighting our vision of relatively small steps in EDI advancement leading to substantial positive impacts.

Research pocket guide: “Striving for inclusive excellence in science and engineering research: a pocket guide”

There is ample evidence that diverse teams of researchers are collectively smarter, more creative, and produce better science (

Phillips 2014;

Nielsen et al. 2017;

Fine and Sojo 2019;

Thomson 2022). However, striving for inclusive excellence in research is not as simple as just recruiting diverse scientists into the field. We need to rebuild academic systems that recruit and train researchers from groups underrepresented in STEM (due to biases and inequities at many systemic levels), while simultaneously adapting research environments to foster inclusion and a sense of belonging for these individuals (

Graves et al. 2022;

Helman et al 2020). This involves identifying and addressing barriers that equity-deserving groups face, raising awareness about bias and discrimination in STEM research, and exposing the hidden curriculum of academic research (

Kang and Kaplan 2019;

Jayabalan et al. 2021). We also need to integrate EDI considerations into designing and conducting research (

Tannenbaum et al. 2019;

Hunt et al. 2022). To tackle these broad goals, we need to start with small actions that will collectively amplify into wide-spread change.

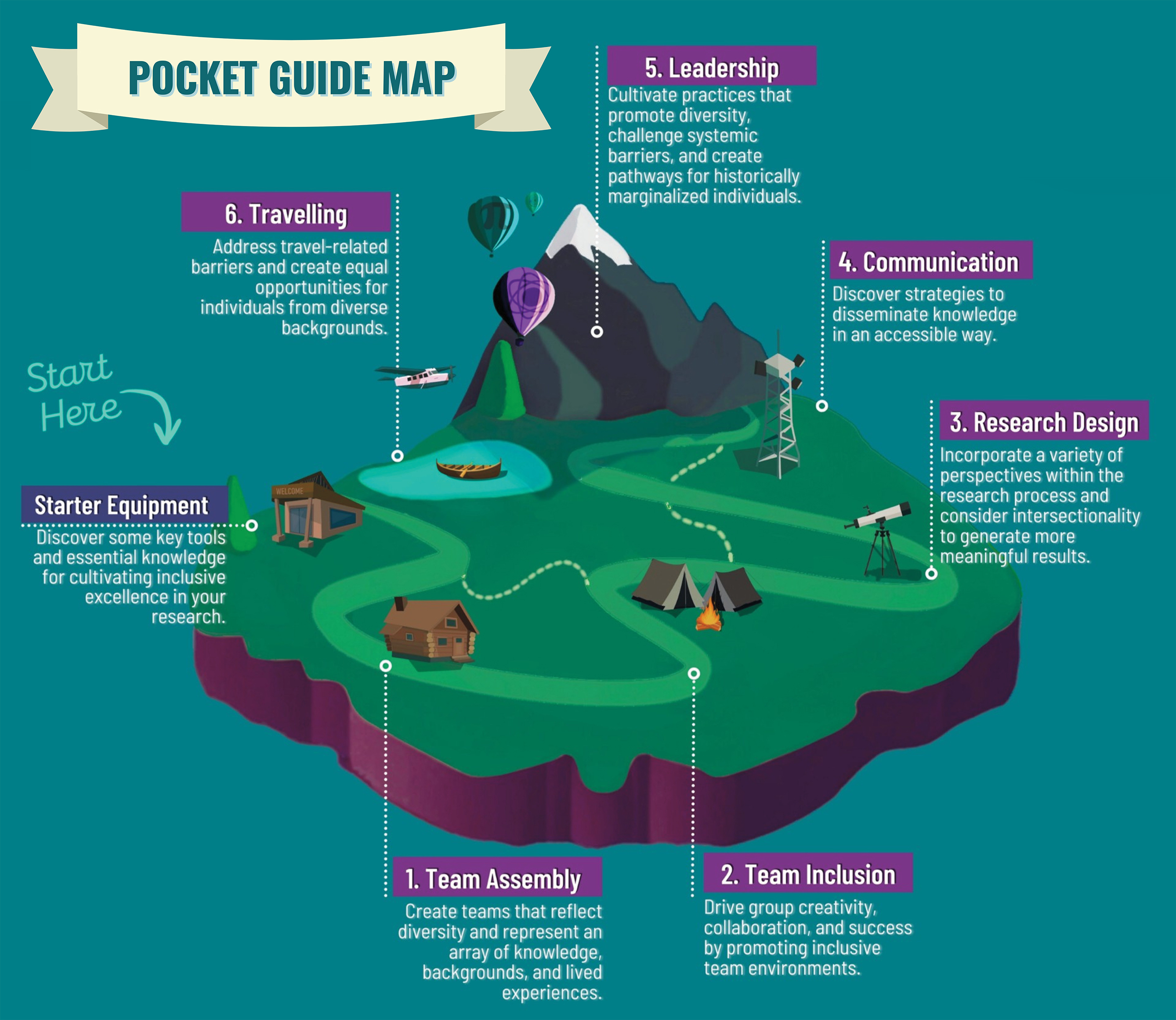

With this ambitious goal in mind, we designed the Research Pocket Guide as a dynamic reference tool for use by anyone engaged in STEM research (

Fig. 3). The materials are accessible to all researchers, including undergraduate and graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, research staff, and team leaders. The goal of this Pocket Guide is to encourage scientists and engineers at every career stage to integrate deliberative equitable practices into their research (

Fig. 5).

The Pocket Guide first offers “Starter Equipment” that caters especially to those less familiar with EDI concepts. The starter resources act as the bedrock to the guide, providing foundational knowledge in key areas such as unconscious bias, allyship, and intersectionality, all within the context of science research. There is a link to a “how-to guide” for advancing EDI (

Thomson 2022) and two introductory activities: (i) EDI Skill Builders Base Deck that includes strategies to alleviate worries when navigating EDI with your team; and (ii) SWOT: EDI Edition, a fundamental activity to assess

Strengths,

Weaknesses,

Opportunities, and

Threats for your team with respect to EDI. The SWOT analysis builds on the use of SWOT as a teaching tool in addition to a results-oriented strategic planning tool (

Helms and Nixon 2010). The SWOT activity offers research teams the opportunity to identify unique strengths and areas of weaknesses where skills, knowledge, and resources are lacking. In doing so, opportunities open for the team to identify actions that could help advance EDI, while recognizing threats e.g., to an inclusive research environment. Finally, the “Starter Equipment” includes tools and references to help craft research proposals, recognizing that many researchers integrate EDI in their funding applications.

With the starter equipment assembled, the Research Pocket Guide is then divided into six main sections (

Fig. 5). Each of these sections is consistently structured with three components: (i) “

Did you know that…” contains key information and statistics that underscore the urgency of EDI initiatives relevant to the section; (ii) “

Have you considered?” describes practical suggestions and small actionable ideas, often including additional materials that were custom-made by the Pocket Guide authors or links to external resources; and (iii) “

EDI Skill builders” describes tangible activities and exercises that may be carried out interactively by research groups.

The first section, entitled “Assembling Research Teams”, provides resources to support equitable practises when building research teams, such as an Equitable and Inclusive Academic Hiring Practises Workshop and links to online modules about bias (

Government of Canada 2024). Suggestions for small actions that will improve hiring practices include advertising open positions in diverse public forums and circulating job ads to dedicated networks that support members of underrepresented groups. This section also underlines the importance of Indigenous research and reconciliation from the start of the research process (

Wong et al. 2020), from weaving Indigenous Knowledge into the scientific method (

Sidik 2022) to including Indigenous researchers and their knowledge (

Gewin 2021).

Recognizing that recruiting a team from across diverse backgrounds is only effective if the research environment promotes a sense of belonging for all team members (

Good et al. 2012;

Lewis et al. 2016;

Kalender et al. 2019), the second section in the Research Pocket Guide focusses on “Fostering Inclusion Within Teams”. For example, we encourage researchers to consider creating a lab handbook (

Tendler et al. 2023) that provides transparency around expectations; a link to a handbook template and additional resources is provided to help make this task easier (

Tendler et al. 2022). A lab handbook can be written by the PI alone or created collaboratively with team members; the exercise of creating this document is a powerful opportunity to stimulate reflection about current lab practices, flag problems or areas of miscommunication within the team, and identify strategies to improve the lab environment and clarify expectations. If a lab handbook already exists, we recommend that the team collaboratively re-evaluate and update this document annually to promote reflection and a sense of belonging. Other ideas for fostering inclusion include organizing regular social gatherings at inclusive venues and openly discussing the importance of taking breaks and requesting time off. We also provide a useful template for conducting anonymous surveys to understand team members’ perspectives about the research environment and to address issues about team dynamics; this aligns with the innovation challenge approach of collecting input data, analyzing it, and implementing strategies within research teams.

The fourth section shifts from conducting research to thoughtfully communicating research findings. We provide practical suggestions for recognizing diverse audiences, such as presentation design accessibility tips, resources for ALT text and closed captioning, and considerations for communication with neurodivergent individuals (

Goulet 2022). We also suggest including a land acknowledgement in your presentations as a small action that supports reconciliation (

Wong et al. 2020).

In the fifth section, entitled “Leadership and Mentorship in Research”, we encourage team leaders to think beyond their individual research labs and advocate more broadly for change. For example, as event organizers, researchers can advocate for designing events that are accessible and welcoming to people with diverse lived experiences, expertise, and identities (

Barrows et al. 2021). As an invited speaker, researchers can raise awareness about lack of inclusion or diversity within a panel or event. Leaders can implement strategies to ensure an equitable distribution of labour to overcome persistent inequities in research (

Macaluso et al. 2016) and service workload for members of equity-deserving groups (

O'Meara et al. 2021). We also provide resources to help recognize and limit unconscious bias when writing letters of reference, and to reflect on communication style (e.g., preferred communication styles for neurodivergent individuals).

The sixth section focuses on travel considerations for researchers who are attending conferences or conducting field work. This section touches on financial barriers, supporting female travel needs related to health, hygiene, and bodily functions when conducting fieldwork, as well as acknowledging the diverse safety concerns that team members may face when traveling (

Bauer 2021).

Finally, there is a link to “Tools and inspiration going forward” which brings together additional resources to complement earlier sections. These include books on creating a culture of accessibility in the sciences (

Sukhai and Mohler 2017), working towards equity for women in science by dismantling systemic barriers to advancement (

Sugimoto and Larivière 2023), and Indigenous wisdom and scientific knowledge (

Kimmerer 2015), a special issue of

Nature (Racism: Overcoming Science’s Toxic Legacy (

Nobles et al. 2022)), journal articles (

Willis et al. 2020;

Ross et al. 2022), as well as other toolkits and web resources.

We believe that the Research Pocket Guide is more than just a collection of resources; it is a potential catalyst for change within the scientific community. It signifies a shift from passive acknowledgment of EDI to proactive engagement and allyship that can be integrated in bite-sized, manageable actions. By offering tools and resources that seamlessly integrate into the various steps of the scientific research process, the guide aims to cultivate an environment where equity, diversity, and inclusion are not just welcomed but recognized as crucial for genuine scientific progress and innovation.