1. Introduction

The connectivity of populations through dispersal is important for maintaining biodiversity in a region, especially following disturbances when ecological communities may be restructured and depleted (

Thompson and Gonzalez 2017;

Chase et al. 2020;

Fontoura et al. 2022). Coastal marine habitats, in particular seagrass habitat and the species it supports, are under increasing threat from human disturbances such as coastal development, nutrient runoff, sedimentation, and the introduction of invasive species (

Orth et al. 2017;

Murphy et al. 2019;

Turschwell et al. 2021). These stressors may impact a population's capacity to maintain local and regional patterns of diversity through increased mortality, reduced fitness, and altered dispersal ability (

Hodgson et al. 2011;

Jonsson et al. 2020). Despite the significance of these projected impacts, there is still a limited understanding of how human activities can alter connectivity patterns and influence biodiversity maintenance.

Population connectivity is the exchange of individuals between populations (

Cowen and Sponaugle 2009), and in the case of a population being associated with a specific habitat type (e.g., seagrass), this connectivity can be made synonymous with

habitat connectivity to emphasize the spatially discrete and structural component of the connectivity (

Saura et al. 2014). Populations connected by dispersal in a region form metapopulations, thus linking regional processes to local species dynamics (

Hanski 1998). Incorporating human impacts into the metapopulation concept can rescale our understanding of the spatial and temporal extent of impacts to seagrass (

Carr et al. 2003;

Gilarranz et al. 2017). An organism that disperses between two populations in seagrass habitat would experience stressors present in both locations. Therefore, a stressor that may only physically occur in one discrete seagrass habitat can then still have regional consequences by affecting the fitness of individuals immigrating and emigrating, thus altering the regional population dynamics of the linked metapopulation (

Spromberg et al. 1998;

Jonsson et al. 2020;

Holstein et al. 2022). Human activities known to impact seagrass may also affect epifaunal invertebrate populations living within seagrass meadows given that measures of invertebrate abundance and diversity have been shown to scale with meadow fragmentation and shoot density (

Lefcheck et al. 2016;

Yeager et al. 2019). In addition, human activities are associated with changes in fish and invertebrate diversity (

Iacarella et al. 2018). Knowing that there can be local impacts on both seagrass and animal diversity, and given the emerging recognition of the importance of connectivity to seagrass systems (

Boström et al. 2010;

Cristiani et al. 2021), it is possible that connectivity could spread impacts or confer population resilience in response to disturbances (

Puritz and Toonen 2011;

Jonsson et al. 2020).

Adequately conserving and managing biodiversity will require considering how connectivity and human impacts interact to influence population dynamics at multiple scales. This criterion is formalized in the

UN Convention on Biological Diversity Aichi Target 11 qualitative elements for designing marine reserves, in which reserves should be “well-connected” and “integrated into the wider seascape”, among other criteria (

UN CBD 2010). Integration implies that a reserve does not exist in isolation, and therefore it is important to consider potential cumulative impacts (CIs) existing in the region when designing a new marine reserve (

Rees et al. 2018;

Meehan et al. 2020). A CI framework quantifies the effect of multiple stressors on an ecosystem component, and it has been adapted to assess impacts at global (

Halpern et al. 2008) and regional scales (

Clarke Murray et al. 2015). At the local scale (e.g., one seagrass meadow), similar CI frameworks have been developed to identify potential impacts (

Murphy et al. 2019;

Nagel et al. 2020). In most CI frameworks, however, the possibility of remote stressors having indirect impacts in other locations through connectivity is not considered (

Jonsson et al. 2020). This may be an important consideration for marine spatial planning, especially when areas of high naturalness are traditionally prioritized for protection (

UN CBD 2008), but where it may be more important to protect an impacted area and limit stressors if it is also highly connected to other areas.

Here, we quantify the potential influence of human activity on the connectivity of seagrass-associated invertebrate populations in the Salish Sea, focusing primarily on British Columbia (BC), Canada with a minor contribution from Washington State, USA. Seagrass meadows form spatially discrete patches of habitat that can be used as a model system for studying connectivity across a seascape (

Boström et al. 2006), and seagrass meadows in BC have been identified as ecologically and biologically significant areas (

Rubidge et al. 2020). We assessed how the local stressors experienced by an animal population in a seagrass meadow may indirectly impact a population in another meadow that is connected by dispersal via deleterious effects on dispersing animals such that fewer individuals disperse or survive dispersal. To predict these regional impacts from local stressors, we combined connectivity and human activity data to model the persistence of regional metapopulations under varying levels of impacts. We hypothesized that metapopulations in regions with higher levels of human activity are more vulnerable because of the potential for impacts to dispersal to cascade among connected populations. This approach results in a framework that can project regional consequences of local stressors, and following validation, it can create new criteria for prioritizing important habitat with a combination of connectivity and naturalness characteristics.

3. Results

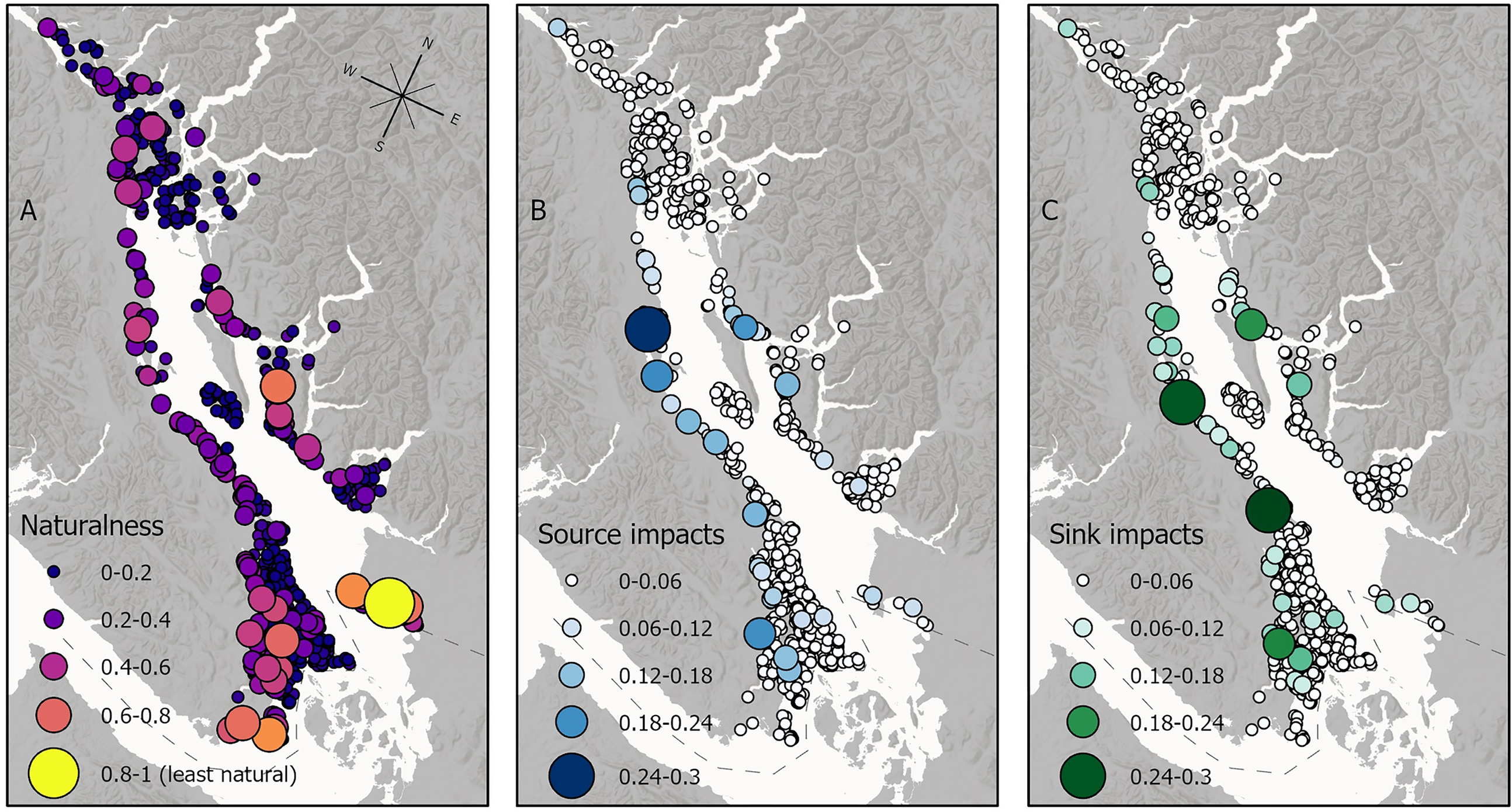

When assessing how the effects of local impacts on seagrasses and their associated faunal communities can transfer by altering animal dispersal, we found that areas of moderate to high naturalness can still experience or transfer the indirect effects of human activity due to patterns of connectivity across the seascape (

Fig. 5). For example, the meadows that are the largest sources of impacts (

Fig. 5B), are not necessarily the most locally impacted meadows (

Fig. 5A)—these meadows are strongly connected to many other meadows and therefore have the potential to disrupt the overall network of habitat connectivity even if they only experience moderate local impacts. We also observed the opposite scenario, in which the least natural meadow (Boundary Bay, BC) is not a significant source or sink of impacts because it is not strongly connected to as many other meadows. Lastly, some meadows that have few local impacts, might still be receiving many impacted recruits because they are connected to highly impacted meadows as a sink population (

Fig. 5C).

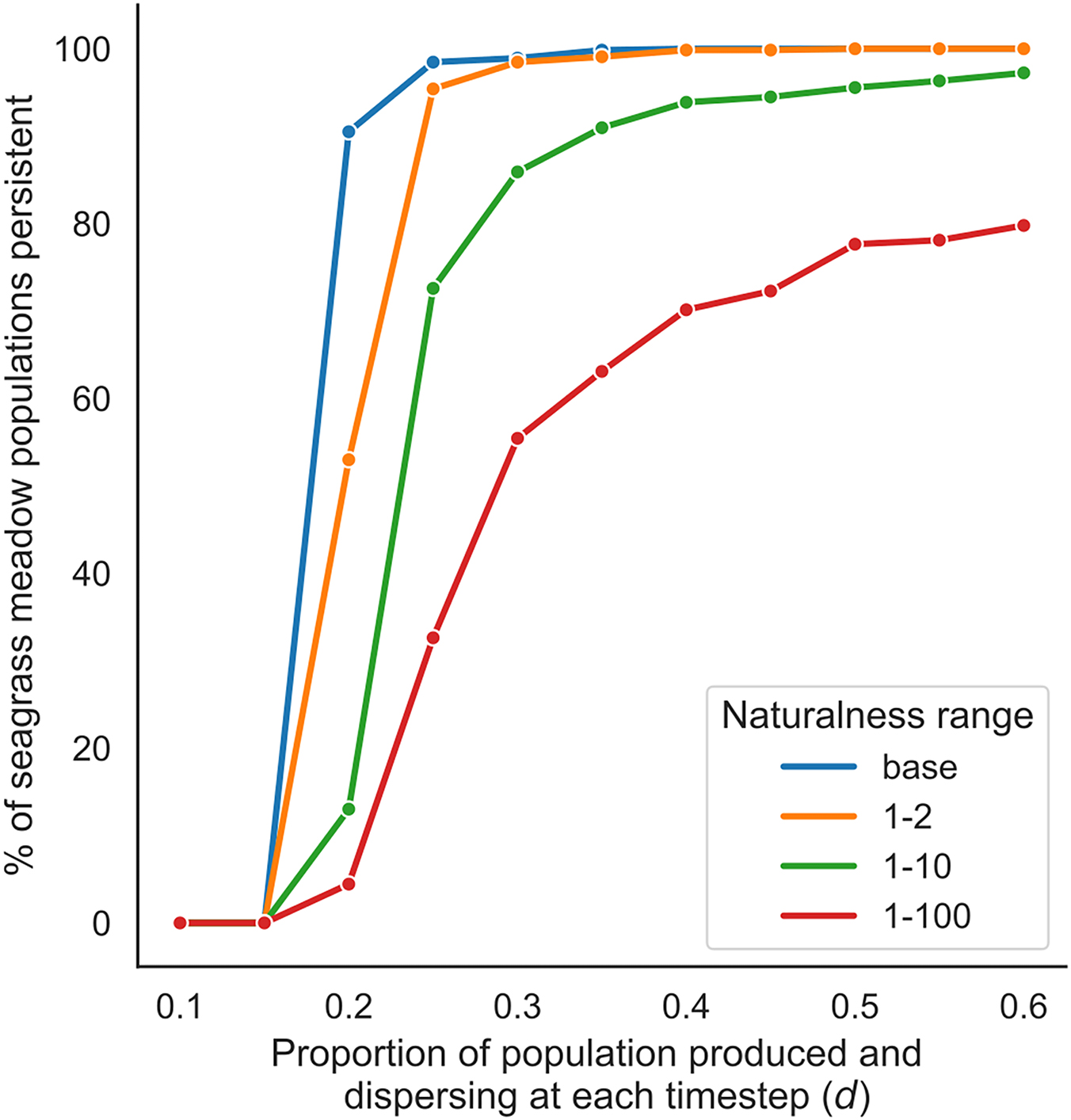

Building on the concept of sources and sinks of regionally transferred impacts, we then tested how changes to dispersal potential may impact metapopulation persistence. We found that human impacts to seagrass invertebrate populations can potentially reduce the number of persistent populations in a region due to reductions in the quantity and survival of dispersing individuals (

Fig. 6). In the absence of regionally transferred impacts, invertebrate populations in nearly every meadow were persistent. We observed only minimal differences in persistence between the

base level and 1–2 scaled range of naturalness. As human impacts intensified, the negative effects on regional population persistence also intensified (i.e., persistence was reduced by a larger amount at the 1–10 and 1–100 scaled ranges). The differences in persistence between ranges were greatest where the percentage of the population dispersing (

d) was just above the mortality rate of the population (i.e., 15%). For example, at a dispersing rate of 20%, persistence ranged from 5% to 95% indicating that the level of impacts has the greatest effect at low levels of exchange.

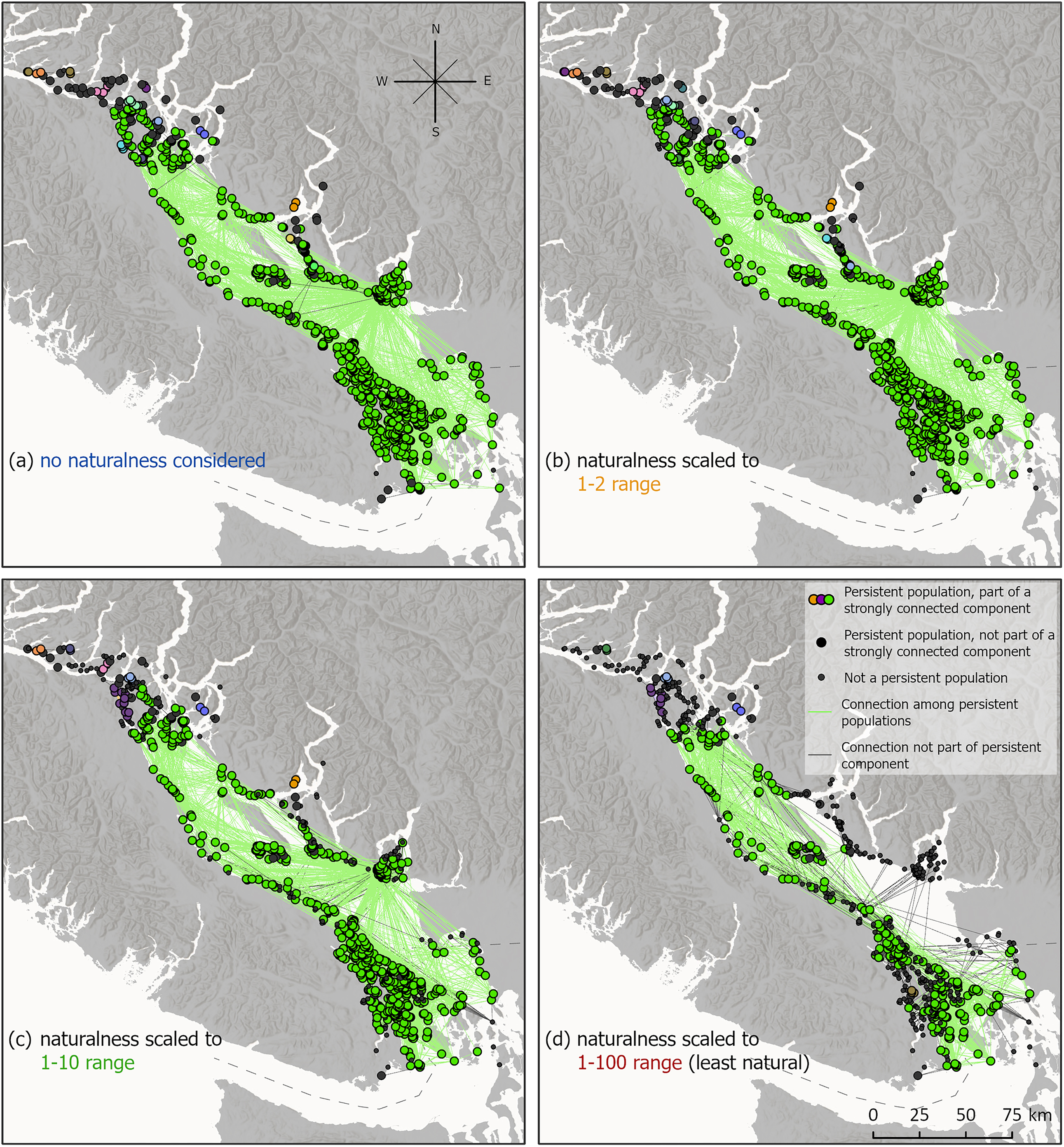

While we observed differences in persistence between ranges of naturalness, these differences were not consistent across the region. Due to numerous connection pathways, populations in many meadows were able to persist despite a reduction in recruits from some pathways. However, naturalness values were not evenly distributed in space—meadows in the southern part of the seascape were less natural—and therefore we observed more of a breakdown and splitting of the metapopulation network in these areas at the 1–10 and 1–100 naturalness ranges (

Fig. 7).

4. Discussion

Using a metapopulation model that incorporates habitat connectivity and anthropogenic pressures, we found that local impacts may alter regional patterns of metapopulation persistence across the seascape for seagrass associated invertebrates. When we allowed impacts to influence connectivity, we saw a reduction in persistence; however, connectivity pathways and probabilities were redundant and robust enough to maintain persistence for most meadows except for a narrow range of invertebrate population values (i.e., when the percentage dispersing was only slightly greater than the population mortality rate). These patterns of persistence emphasize the importance of considering habitat as a network and the topological characteristics that emerge from the connectivity of the network.

A metapopulation model parameterized with dispersal connections that vary in magnitude and direction can uncover if there is redundancy of connectivity in the system that can overcome any reductions in dispersal from human activity (

Minor and Urban 2007). This demographic “rescue effect” lowers the impact of local stressors and buffers regional biodiversity against local population size fluctuations (

Thompson et al. 2016;

Gilarranz et al. 2017;

Harrison et al. 2020). By combining our metapopulation model with estimates of human impacts, we demonstrated a “safe operating space” of the network (

Gonzalez et al. 2017), in which the persistence of the metapopulation was stable at low levels of impacts but was destabilized when the combination of impacts had a large cumulative effect. From these predictions, we can identify seagrass meadows that are both topologically important and highly impacted, where their loss would significantly reduce network connectivity and threaten overall metapopulation persistence. A key conservation challenge will then be to reconcile the priority to conserve the most natural meadows (

UN CBD 2008;

Rubidge et al. 2020) with the need to reduce impacts in and protect central but degraded meadows that potentially have greater regional influence.

While our model is largely conceptual, there is evidence of the effect of local and regional impacts on nearshore systems that support our findings. Cumulative effects from activities similar to those in this study, such as moorage and foreshore development, have been shown to reduce seagrass meadow area (

Rees et al. 2023), CIs can influence invertebrate species assemblages among meadows (

Adamczyk 2022), and nutrient inputs to seagrass meadows (similar to those from agriculture) can reduce invertebrate feeding rates (

Tomas et al. 2015). Furthermore,

Iacarella et al. (2018) found that the same suite of human pressures used in this study was correlated with a reduction in diversity of eelgrass associated fish communities in the Salish Sea. Assuming that these local pressures can impact other seagrass associated communities, we were then able to consider if these impacts are indirectly transferred and influence the dynamics of distant populations. For example,

Jonsson et al. (2020) demonstrated that connectivity increased the CIs to blue mussel populations in the Baltic Sea by as much as 30% due to reduced larval production in source populations resulting in reduced recruitment opportunity in sink populations. Similar to our study, impacts from connectivity were not distributed equally across the seascape but were significant in specific areas. This pattern highlights the importance of considering connectivity for quantifying the full regional impact of human activities that otherwise would not be obvious if only considering impacts at their source (

Jonsson et al. 2020). In another related study, point-source wastewater pollution in California was found to increase larval mortality and limit pelagic larval dispersal of sea stars. thus reducing connectivity and isolating populations of an otherwise high gene flow species (

Puritz and Toonen 2011). Seagrass in the Salish Sea is predicted to be well-connected by invertebrate dispersal (

Cristiani et al. 2021), however, as demonstrated in

Puritz and Toonen (2011) and in our high CIs scenario, certain stressors can have significant impact on what is assumed to be a connected system.

Going forward, it will be important to validate and improve estimates for the three primary modeled components of the study: (1) connectivity, (2) metapopulation persistence, and (3) human impacts.

Cristiani et al. (2021) discusses the technical limitations of the biophysical model, however, most fundamental is that our connectivity model only considers the reduction in

potential connectivity, i.e., transport and settlement. The connectivity-impacts framework could be extended to understand the effects of human activity on

realized connectivity, in which dispersing individuals successfully settle, survive, and reproduce in the sink meadow—creating a genetic connection (

Cowen and Sponaugle 2009). Assessing this kind of connectivity would require measuring genetic structure in the Salish Sea, which could then be used to validate connectivity estimates from the biophysical model (

Mertens et al. 2018;

Wilcox et al. 2023).

To account for the uncertainty in the metapopulation model, we quantified persistence across a range of naturalness and population dynamic values. However, there are many areas of the modeling approach that can be refined to reduce uncertainty. Our results show that population persistence was not sensitive to moderate human activity if reproduction far exceeds mortality. When these rates were similar, however, persistence was much more sensitive to human impacts. This range of possible parameter values in the metapopulation model can be narrowed with species-specific empirical data, such as population mortality and reproduction rates obtained from experimental and observational studies. In addition, local impacts to the sink meadow could be incorporated into a more complex metapopulation model that applies meadow specific reproduction and mortality rates to further influence overall persistence through time. An approach that also incorporates the influence of species interactions and additional environmental conditions on fitness would then move us closer to a metacommunity model (

Thompson et al. 2020).

A more accurate assessment of human impacts will require additional impact data, species-specific vulnerabilities to stressors, and knowledge of how stressors combine. Our model considers stressors from six activities, but additional activities at local, regional, and global scales are known to impact seagrass habitat (

Agbayani et al. 2024;

Murphy et al. 2024). For example, local activities like log storage can directly modify seagrass habitat, and regional development in the watershed, such as roads, can increase sedimentation (

DFO 2023,

2024). Climate change indicators such as sea level rise, ocean temperature, acidification, and freshwater outflow temperature can impact seagrass (

Weller et al. 2023;

Murray et al. 2024) and temperature change can alter invertebrate dispersal (

O'Connor et al. 2007;

Gerber et al. 2014). Our impacts model could also be improved by incorporating a full CI assessment as opposed to a simple additive approach. This would first involve quantifying the vulnerability of seagrass and invertebrates to each stressor. For example, the impacts on seagrass from logging with proper precautions may be less than the impacts from agriculture in the watershed. This vulnerability of an ecosystem to stressors could be determined from qualitative expert-opinion scores (

Teck et al. 2010) or from estimates of species’ responses to stressors (i.e., stressor-response curves), which provides an empirical relationship that can be validated with experimental and field observational studies (

Rosenfeld et al. 2022;

Jarvis et al. 2024). Lastly, we could improve our impacts model by understanding how stressors combine to have an effect greater than the sum of their parts (

Halpern and Fujita 2013). For example, gradients of light and temperature have an interactive effect on eelgrass growth rate suggesting that multiple stressors can have nonlinear impacts (

Dunic and Côté 2023).

We have demonstrated a framework that can be used to assess whether local human impacts influence the persistence of populations across a seascape by altering the quantity and survival of organisms dispersing among populations. This approach integrates two concepts which operate across scales: CIs and connectivity. Understanding these two concepts will be important for managing seagrass habitat and associated species in a landscape context, in which patterns of distribution, dispersal, and impacts will interact to influence regional management strategies (

Murphy et al. 2021). Dispersal and the spread of impacts operate across borders, and it will be essential to coordinate research efforts to generate consistent datasets among Federal, Indigenous, Provincial and State governments. Although eelgrass is declining globally (

Dunic et al. 2021), eelgrass in nearby Puget Sound, Washington is stable and resilient overall, despite a significant increase in local human and climatic stressors (

Shelton et al. 2016). Assessing the relevance of managing for human impacts in the Salish Sea will therefore require a deeper understanding of seagrass and invertebrate responses to stressors and the mechanisms (e.g., dispersal) that allow for resilience to these stressors. Ultimately, refining and validating our models will increase their utility and promote their incorporation into broader marine spatial planning efforts.