1. Introduction

Hypertension is the leading cause of premature mortality worldwide, with an estimated prevalence of 20%–30% among adults with essential hypertension (

Mills et al. 2020;

Sabri et al. 2021;

Zhou et al. 2021). The prevalence varies significantly across regions, with high-income countries demonstrating modest declines in hypertension rates while marked increases are observed in low- and middle-income countries (

Mills et al. 2016;

Zhou et al. 2017). In pediatric populations, hypertension predominantly presents as secondary hypertension, often a result of inadequate weight management and metabolic syndrome, while essential hypertension prevalence ranges from 4.7% to 19.4% (

Kliegman et al. 2007;

Sabri et al. 2021).

The last two decades have seen a pronounced rise in the prevalence of pediatric hypertension, driven by a complex interplay of physiological and environmental factors. Changes in family structure, such as the rise in single-child households, have been suggested as contributing factors to this trend (

Zeng et al. 2013;

Song et al. 2019). Pediatric hypertension, defined as blood pressure exceeding the 95th percentile for a child's height or weight, has been closely linked with the development of essential hypertension later in life and an increased risk of lifelong cardiovascular complications (

Raitakari et al. 2003;

Falkner and Daniels 2004;

Kliegman et al. 2007;

Sabri et al. 2021). Due to the significant associated risk for various cardiometabolic diseases—including heart failure, myocardial infarction, sudden cardiac death, cerebrovascular accidents, and chronic kidney disease—early detection through routine blood pressure screening from the age of three is advocated to improve management and outcomes (

Kliegman et al. 2007).

In the ongoing exploration to unravel the etiologies and contributing factors of hypertension, considerable research has focused on environmental determinants. Among these, the impact of birth order on systolic and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) has been investigated; however, studies yield inconsistent outcomes. While Wells and Lawlor identified a propensity for firstborns to develop hypertension during childhood and early adolescence (

Lawlor et al. 2004;

Wells et al. 2011), other studies found no significant association between birth order and blood pressure levels (

Jelenkovic et al. 2013;

Howe et al. 2014).

Understanding the role of birth order, as a non-modifiable risk factor, is crucial for the precise evaluation of modifiable risk factors, through better recognition and estimation of risk factors effect sizes and subsequently, designing targeted interventions as necessary (

Siervo et al. 2010). Despite many individual studies addressing this topic, systematic reviews and meta-analyses synthesizing the evidence base are lacking. This study aims to fully evaluate the relationship between birth order and blood pressure, to enhance our understanding of its significance, strength, and quality. Furthermore, identifying risk factors for adverse cardiovascular outcomes could provide hints toward early preventive strategies to slow disease progression. Thus, our research seeks to clarify the association between birth order and the risk of systolic and diastolic high blood pressure.

4. Discussion

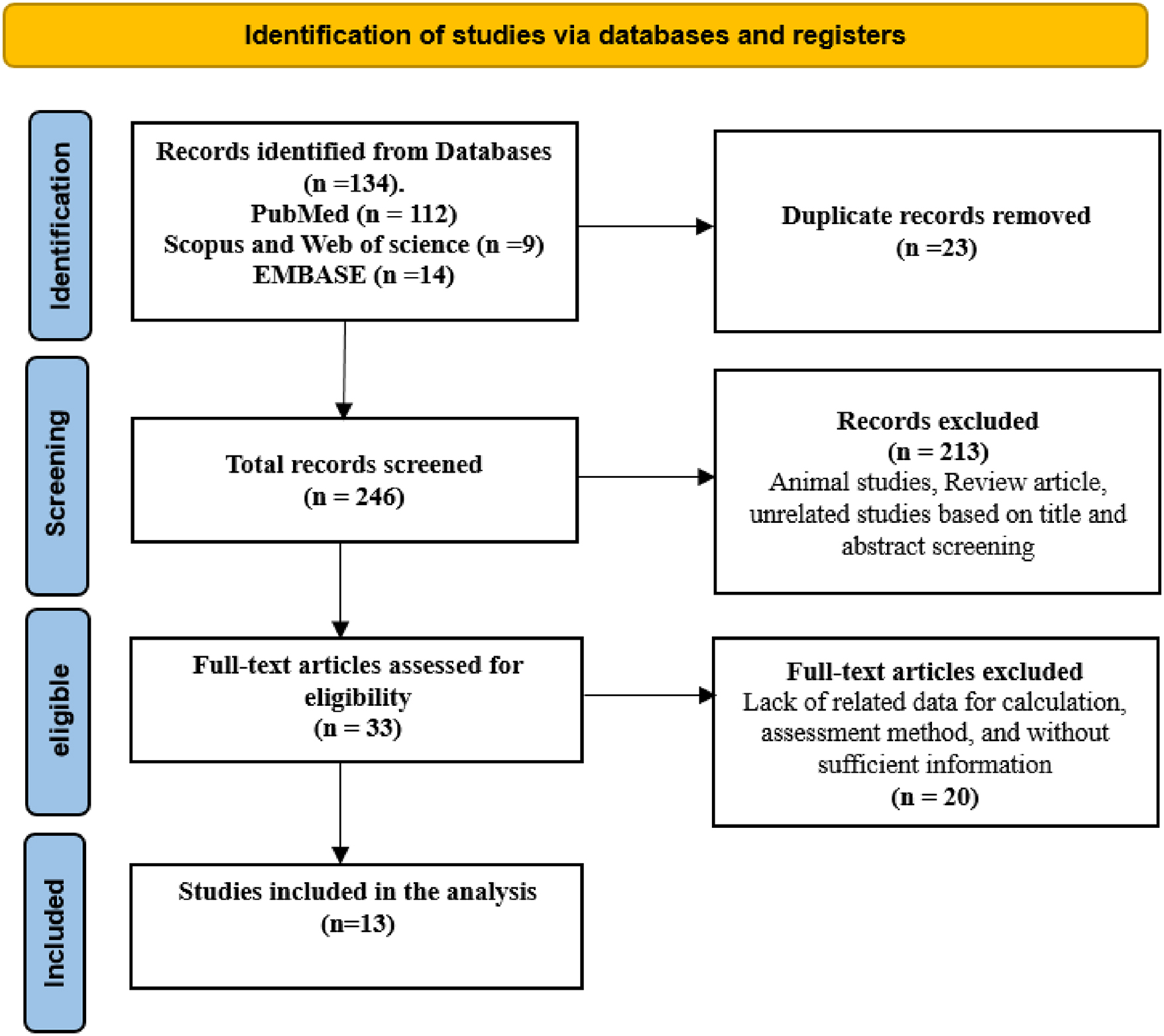

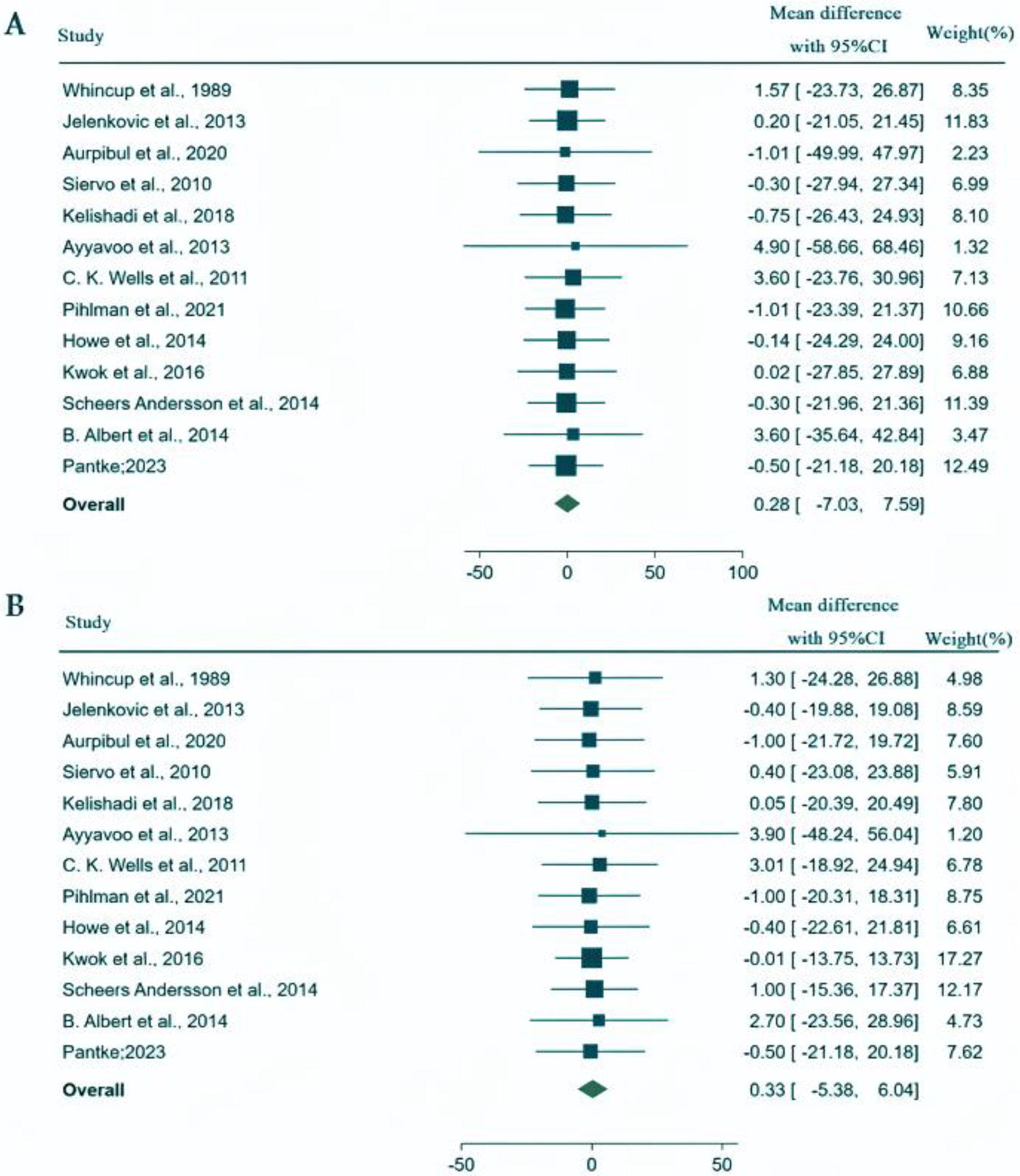

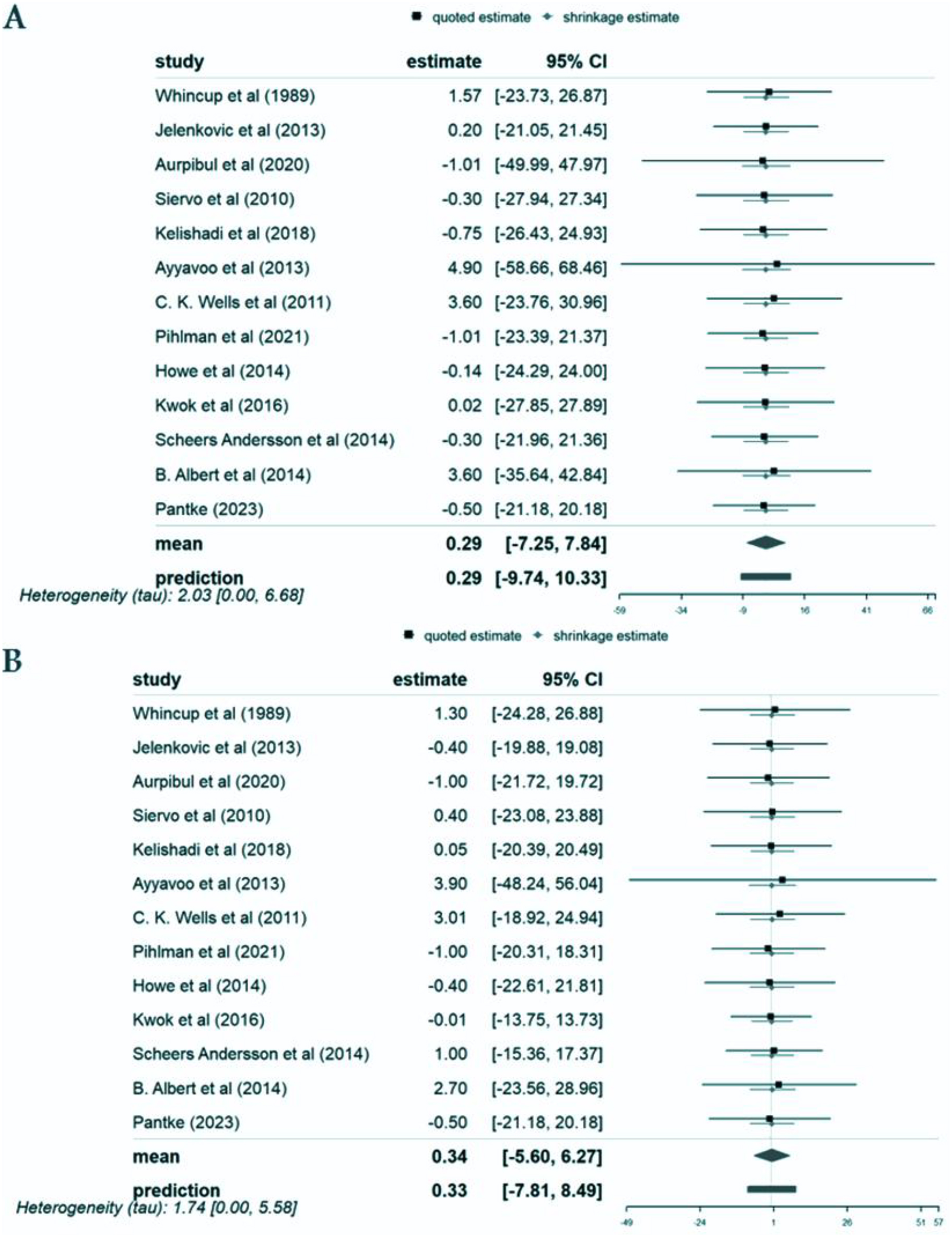

We conducted our analysis using data from these 13 studies carried out in Europe, Asia, and the Americas involving a total of 1113 639 participants, of which the populations were 1078 834 youth, 15 915 from pediatric populations and 18 890 participants from combined youth and pediatric populations. We found that the mean SBP and DBP mean differences between first-born and later-born individuals were 0.28 mm Hg (95% CI: −7.03, 7.59) and 0.33 mm Hg (95% CI: −5.38, 6.04), respectively. These mean differences did not represent a statistically significant effect. Similarly, analyses by patient populations, geographical locations, and study types showed no statistically significant differences in blood pressure about birth order.

To our knowledge, this study represents the first systematic review and meta-analysis examining the association between birth order and both systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Given the global rise in hypertension and obesity among young populations (

Helen et al. 2013), understanding these associations is crucial for identifying early-life risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, major causes of mortality in industrialized nations (

Gaziano 2007).

The relationship between birth order and cardiometabolic risk factors has been a subject of extensive investigation in recent years. Numerous meta-analyses and systematic reviews support the notion that birth order significantly influences risk factors such as obesity, dyslipidemia, diabetes (types 1 and 2), cardiovascular disease, and insulin resistance. Prior meta-analyses have identified a notable correlation between lower birth order and an increased risk of obesity, and suggested a protective effect of higher birth order against childhood-onset type 1 diabetes, especially in children under 5 years of age (

Meller et al. 2018). Schooling CM et al.’s findings further indicate that birth order may influence developmental patterns with lasting health implications (

Meller et al. 2018).

Contrary to expectations and existing hypotheses, our findings do not support a significant impact of birth order on systolic and diastolic blood pressure. This aligns with the work of Jonathan C. K. Wells et al. (

Gaziano 2007), which, despite initial observations of higher systolic blood pressure in firstborns among adolescents, found no statistically significant association after adjusting for relevant maternal and child factors. Conversely, studies by (

Ayyavoo et al. 2013) and others have reported associations between birth order and increased blood pressure, suggesting a potential risk of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases later in life.

Laura D. Howe and colleagues' exploration of birth order and cardiometabolic risk factors revealed weak and inconsistent associations, further complicating the narrative. Their research speculates on the influence of prenatal and postnatal environmental differences between first-born and later-born children, which could affect cardiovascular and metabolic system development, thus influencing blood pressure and body composition in later life (

Howe et al. 2014).

First-born children's exposure to a restricted nutrient supply during intrauterine growth due to the structural properties of the uterine spiral arteries is hypothesized to contribute to lower birth weights and, consequently, a higher risk of hypertension (

Valdés-Ramos et al. 2002;

Ayyavoo et al. 2013;

Kwok et al. 2016;

Pantke et al. 2023). This phenomenon, coupled with impaired glucose metabolism and reduced insulin sensitivity known as the thrifty phenotype hypothesis, underscores the complex interplay of physiological and environmental factors in the development of hypertension (

Siervo et al. 2010;

Pihlman et al. 2021).

The association between birth order and various cardiometabolic risk factors has been a point of controversy. Differences have been reported in outcomes like weight, obesity, and hypertension between first-born opposed to later-born offspring. Hypertension is a well-established cardiometabolic risk factor, establishing that essential hypertension accounts for nearly 95% of adult populations (

Carretero and Oparil 2000). Therefore, a better understanding of the factors contributing to the development of hypertension or influencing blood pressure is fundamental in enhancing the effectiveness of prevention and treatment strategies. Among these factors, the role of birth order as a non-modifiable risk factor has been an issue of great interest (

Ghandi et al. 2018). A better understanding of how birth order contributes to blood pressure could go a long way in unraveling the tangled threads between modifiable risk factors and hypertension, sharpening our capacity to prevent and manage this rampant condition and enabling us to provide more individualized recommendations in clinical settings.

For clinicians, these findings provide reassurance that birth order should not be considered a significant risk factor for hypertension or blood pressure abnormalities. Other established risk factors, such as age, obesity, physical activity, smoking, diet, and genetic predispositions, should remain the primary focus in assessing and managing blood pressure. Clinicians can be confident that while birth order might influence other developmental aspects (e.g., academic achievement, personality), it does not play a major role in determining blood pressure levels. This allows for more targeted interventions focusing on modifiable lifestyle factors, rather than unnecessary concern about birth order in cardiovascular health assessments. The clinical takeaway from this study is that birth order does not appear to influence systolic or diastolic blood pressure in a clinically significant manner. Clinicians should not consider birth order as an important factor when assessing a patient's risk for high blood pressure or cardiovascular disease. Instead, emphasis should remain on well-established risk factors that have a clear and substantial impact on blood pressure regulation.

Several limitations need to be addressed when interpreting this study's results. First, we could not measure family size or age gaps between siblings, which might impact the relationship between birth order and cardiometabolic risk factors. Secondly, parenting styles and children's use of technology have changed considerably over the past two decades, and these changes may alter the dynamics between parents and children and the potential impact of birth order on those dynamics. These factors may not be sufficiently captured in the present study. Another important factor known to contribute to the cardiometabolic risk profile is prematurity. Unfortunately, none of the studies included had data available on the prematurity status of participants. Sex is a well-known determinant of cardiometabolic risk profile; unfortunately, none of the studies reported results by gender. Therefore, this important variable could not be included in our analysis.

Although observational studies generally provide less convincing evidence than randomized controlled trials, we evaluated the methodological quality of the studies included in this meta-analysis. However, the fact that our study is based on thirteen published studies limits its external validity and generalizability. In addition, it was not stated whether the included studies distinguished between essential (primary) and secondary hypertension: this may affect the accuracy or the interpretation of outcomes.

Considering the gaps within the current literature, future studies should focus on a comprehensive evaluation of the differences between the cardiometabolic profiles associated with first-born and later-born children through adolescence to adulthood. Such studies should include factors such as age gap, sex, underlying diseases, physical activity, nutritional habits, and psychiatric profiles. In this way, more definitive results can be obtained better to understand modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors of cardiometabolic health, enabling more accurate recommendations regarding clinical practice.