Introduction

Emerging zoonotic diseases present a threat to the health of wildlife and humans (

Woolhouse and Gowtage-Sequeria 2005;

Jones et al. 2008). In fact, over 70% of novel infectious diseases are of zoonotic origin (

Jones et al. 2008) with further spillover from animals to humans expected as a result of the intensification of habitat loss from agriculture and infrastructure expansion globally

(UNEP 2020). Critical to the prevention and management of zoonotic disease threats is consistent monitoring, implementation of pertinent research, information sharing and knowledge integration, and the establishment of clearly defined pathways for collaboration and communication among multidisciplinary partners (

Mackenzie and Jeggo 2019;

UNEP 2020). As partners are likely to stem from diverse backgrounds and opinions, representing organizations with overlapping—though undoubtedly differing—mandates, common priority items can create a shared responsibility and potential to streamline management actions and generate collaborative and innovative solutions (

Häsler et al. 2020).

While multiple avenues for collaboration exist in the management of zoonotic diseases, prioritization activities and equal engagement from partners actively working in zoonotic disease surveillance and management are considered to be a leading approach to address complex multisectoral problems because of the cost-effectiveness and ease of implementation (

Salyer et al. 2017). Approaches that create shared responsibility are particularly suitable when confronted with novel challenges laced with uncertainty and unpredictability (

Häsler et al. 2020), as is often the case with emerging infectious diseases (

Mazzamuto et al. 2022). Therefore, by developing mechanisms for engagement and enhancing One Health capacity among partners, there is a greater ability to effectively tackle complex problems in rapidly changing environments.

Within the context of threats of emerging concern, there is a need to focus research and monitoring efforts. This central question of “what to do first” is common to many fields where there are more questions than resources to address them. Over the past few decades in the world of conservation, this need to prioritize what to focus on has become more common as the biodiversity crisis deepens. Determining what themes, issues, or needs to focus efforts have resulted in undertakings such as annual horizon scanning, evidence synthesis reviews, as well as other processes (

Hines et al. 2019). The purpose being that by better aligning research with policies and mandates, we can make the results more relevant to management decisions, and more likely lead to actions resulting in conservation successes on the ground (

Rudd 2011). These processes are particularly critical when emerging threats pose a suite of possible research and monitoring that could be worked on, but as with most emerging threats, resources are ramped up in a reactive manner, and thus choices need to be made on what to focus on first.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAIV) H5N1 subtype clade 2.3.4.4b is a newly emerging virus in Canada and North America, with significant potential impacts on wildlife and domestic animal health (

Caliendo et al. 2022;

Giacinti et al. In prep). With the first detection late in 2021 in North America, there was a national interagency collaborative effort to enhance AIV surveillance in wild birds. Canada's Interagency Surveillance Program for Avian Influenza Viruses in Wild Birds has been in place since 2005 and includes several surveillance components but primarily opportunistic sampling of sick and (or) dead and live apparently healthy wild birds (

Giacinti et al. in prep). For dead/sick bird surveillance, work was led by the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative (CWHC), and by provincial, territorial, and Indigenous governments (PTIs). Live bird and environmental sampling was led by Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) in collaboration with PTIs and academic partners. Importantly, the sampling in 2022 was largely opportunistic due to timelines and permitting requirements associated with migratory bird field programs. In Canada, HPAIV has been detected in every province and territory, and mortality in at least 40 000 wild birds has been attributed to the virus in 2022 (

Giacinti et al. In prep).

Given the long-term persistence of the current HPAIV in Europe and the continued detections in North America, it was recognized in 2022 that ECCC and partners needed to prioritize HPAIV-related information that needs to inform surveillance planning and identify avenues of potential collaboration between ECCC and external/interagency partners. Here, we describe an expert elicitation exercise that was undertaken using a collaborative One Health approach, with the following three objectives:

1.

Determine top priority HPAIV-related information needs under five themes (i.e., assessing population level impacts in wild birds, data management, reporting and communication, disease dynamics, surveillance methods and protocols and, pathogen transmission).

2.

Determine criteria to guide actions on disease surveillance and research when multiple species are affected by HPAIV.

3.

Given current resources, determine the feasibility of meeting top priority information needs, identify the major barriers/program areas that determine progress toward meeting them and establish relative importance of the highest priority under-resourced needs.

We also retrospectively reflect on the utility of the structured communication process as a tool. This tool can be adapted and employed at regular intervals across wildlife health programs to collaboratively inform evidence-based planning and policy making and as a way to support transparency in the science-to-policy cycle.

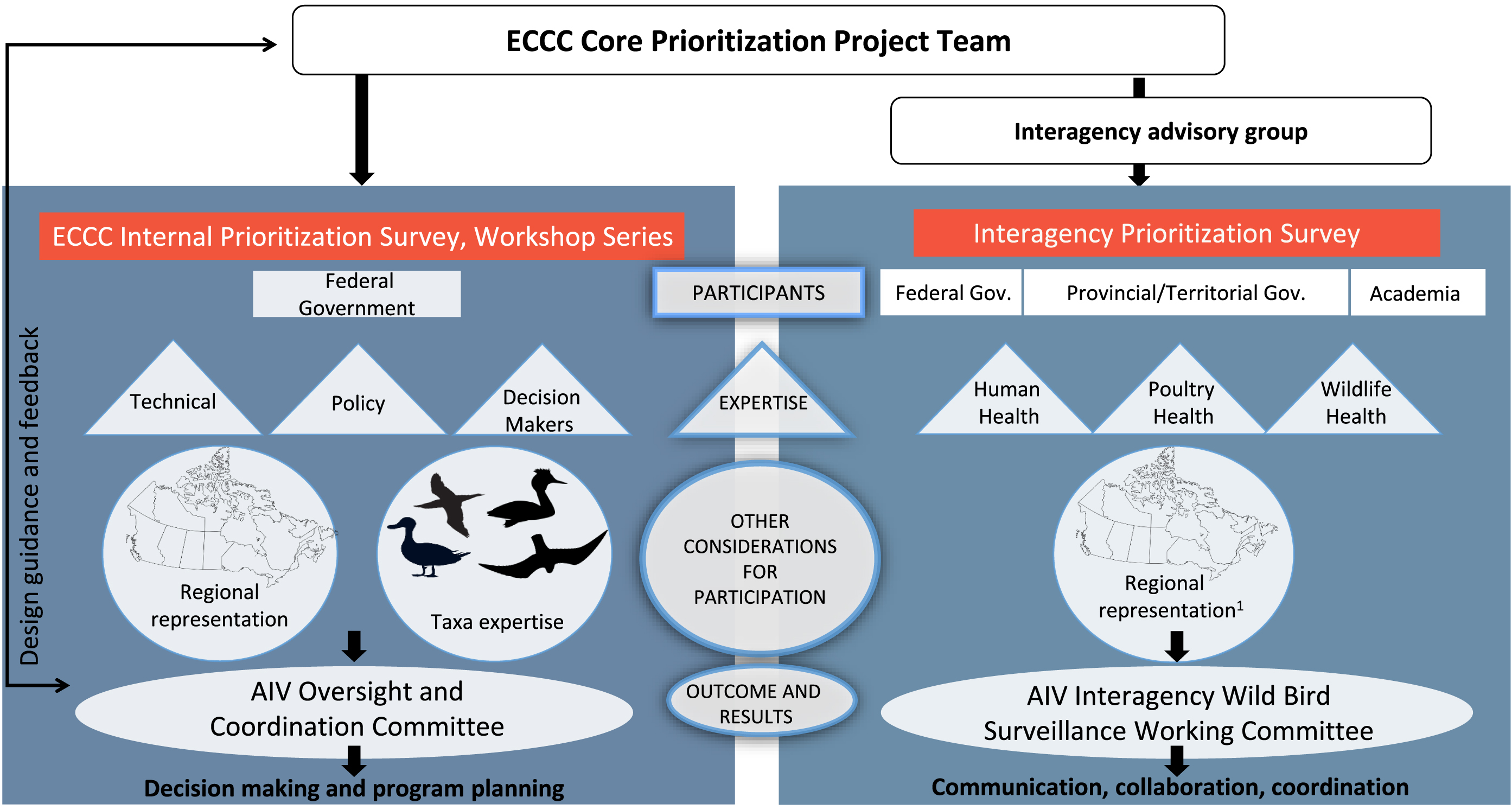

Approach for Objectives 1 and 2: determining top priority HPAIV-related information needs and criteria to guide actions on disease surveillance (surveys and workshop 1)

We, (the ECCC Core Team), evaluated expert opinions for the ECCC group and interagency group through a survey customized for each group. To prioritze information needs (Obj.1) based on consensus within the ECCC group, we used a modified Delphi technique that, in addition to the survey, involved a post-survey workshop (i.e., Workshop 1). The Delphi technique is a primary research tool that gathers and distills expert opinions on a complex topic through a structured group communication process (

Hasson et al. 2000). A Delphi expert elicitation process is commonly characterized by a series of survey iterations with controlled feedback via the principal investigator to find points of consensus and (or) dissensus among participants using a statistical estimator of group opinion (

Dalkey 1969). We considered this approach to be a design compatible with values consistent with One Health concepts such as listening/reflecting, information sharing, and the consideration of multiple viewpoints. Multiple iterations allow for participants to incorporate new knowledge and provide updated opinions based on the opinions and reasoning of their peers, and due to the anonymity of the process, participants can share ideas without fear of judgment, which can mitigate the influence of unequal power dynamics (

Dalky and Rourke 1972;

Frewer et al. 2011). In our modified process, since multiple survey iterations were not practical due to time constraints and participant workloads, Workshop 1 served as an opportunity in which ECCC participants could review their peers’ qualitative response justifications and take them under consideration as they re-rated survey items that did not already achieve consensus in the initial survey (see Workshop 1).

Due to time constraints, the interagency survey was issued without a follow-up survey iteration or workshop, and thus is not reflective of a Delphi approach per se. However, we were able to use results from the many items that did reach consensus in the intial surveys as well as the most popular criteria to guide action on surveillance (Obj. 2) to find areas of agreement between the two participant cohorts and to look for areas of joint priority and possible avenues of collaboration.

Survey design, implementation, and analysis

To design the surveys for the internal ECCC group of experts (CWS and STB) and the interagency One Health partners, the ECCC Core Team and Interagency advisory group consulted with their respective colleagues to produce a vetted, refined information needs list that reflected their own sector's themes and mandates to be evaluated by their peers in the survey (Obj. 1) and generate a list of suggested criteria that should guide surveillance actions that survey participants could choose from (Obj. 2). The ECCC Core Team blind coded the information needs under five themes that encapsulated the main areas of focus for both cohorts: assessing population impacts in wild birds; disease dynamics; pathogen transmission; surveillance methods and protocols; and data management, reporting, and communication. These themes were coded for analysis purposes, and needs in the survey were not organized by theme.

Survey items in their entirety are shown in the Supplementary material (Tables S1 and S2). Both the internal ECCC and interagency survey began with a consent page that described the survey objectives, survey content, and how the data would be used (Q1, Supplemental material Tables S1 and S2). The knowledge that was acquired during this process was specific to professional opinion on a matter that the experts were predetermined to have (e.g., through their formal professional roles). The first section of the surveys collected demographic information and included questions to capture respondent diversity, experience, and self-reported expertise in six categories of birds (i.e., waterfowl, seabirds, raptors, upland birds, waterbirds, and landbirds), among others. The demographic information collected varied slightly between the two surveys (Tables S1 and S2).

In the survey sections pertaining to Objective 1, the aim was to assess the perceived priority level of the ECCC or Interagency advisors’ information needs (31 and 27 needs, respectively). We asked the participants to rate each information need on a five-point Likert scale according to perceived priority level (i.e., Essential, High, Medium, Low, Not at all a priority), with priority defined as the intersection between urgency and importance.

Table 1 illustrates how we then determined the priority level (point-of-consensus) for each of the information needs as well as the degree of consensus among the participating group by using an approach applied by Robert de Loë to explore complex policy questions via a policy delphi (

de Loë 1995).

If considering responses from two adjacent categories on the Likert scale shifted the consensus up a level/levels (e.g., from medium to high), the consensus was recorded as spanning two categories on the scale (

Table 1). For example, if an information need was found to be “High” priority at a low, single category consensus level (e.g., 51%) and considering the contiguous “Essential” priority responses (e.g., 39%) moved the consensus level to high consensus (at least 80% of votes spanned these categories), the need was recorded as high consensus and the point-of-consensus recorded as “Essential–High” (E-H). Since the ECCC group completed their survey first, the results (i.e., top priority information needs and most popular criteria) were included as items in the interagency survey alongside the additional information needs identified by the Interagency advisory group. There were a total of 12 information needs common to both surveys.

The participants were also asked to justify some of their ratings in an open-ended comment following each rating to provide context for results and content for subsequent workshop discussions. Respondents were instructed to skip any information need that they felt they could not adequately rate based on their expertise. In the survey section pertaining to Objective 2, the aim was to establish the most popular criteria that the respective cohort thought should be used to guide actions when multiple species are affected by HPAIV. Survey participants could choose five from the predetermined list and were prompted for additional suggestions.

We distributed the online survey, which consisted of 44 questions to 65 participants in ECCC's CWS and STB groups and included both scientists and managers. The survey was open to participants from 16–26 January 2023. The interagency survey consisted of 39 questions and was distributed on 30 March 2023 to 62 potential participants. Participants of the interagency survey were composed of AIV IWBSC members and respondent referrals to ensure that a range of diverse perspectives under the One Health umbrella were represented. To accommodate some members of the AIV IWBSC that were not able to complete the survey during the original distribution period, we re-opened the survey for 3 days, which allowed for these additional entries.

Workshop 1: ECCC revote on “No-Consensus” information needs (2 March 2023)

Workshop 1 was held virtually and open to all participants of the internal ECCC survey. The overall aim was to reach consensus on the five information needs that did not achieve consensus on a priority level during the course of the ECCC internal survey. For each of those needs, we presented workshop participants with anonymous rating justifications that had been entered into the survey by their colleagues. We presented rationales that offered unique insight, or served as a counter-perspective to rationales of those participants that rated the same need at a different priority level. Participants were allowed approximately 5 min to consider the evidence and bring any additional points to the group either verbally or via the online chat (both methods attributable) for consideration before the participants anonymously re-rated the information need.

Results

Online survey demographics

The ECCC survey response rate was 74%. Sixty-nine percent of respondents were from CWS, 23% from STB, and 8% non-reporting. Respondents’ average number of years in their current position was 8.5 years (median = 5.5 years), and the average time spent at ECCC was 10 years (median = 9 years). Respondents' work was focused mainly in the Atlantic region followed by Ontario and Quebec (Fig. S3). Self-reported expertise for six bird groups varied across taxa (Fig. S4). Expertise at any level was highest for waterfowl followed closely by waterbirds and seabirds. There was a higher proportion of respondents reporting a high level of expertise in waterfowl and seabirds relative to the other bird categories (Fig. S4).

The interagency survey response rate was 48%, with the survey distributed to a total of 62 experts from the Interagency Wild Bird Surveillance Working Group. Twenty respondents applied wild bird surveillance in the context of wildlife health, eight in animal health, and two in public health (Fig. S5). Overall, the respondents were almost equally split between federal and provincial organizations (43% and 39%, respectively), with the balance representing academia via the CWHC (18%) (Fig. S5). Similar to the ECCC group, the interagency group represented people from across several regions, including those focused nationwide (40%), Atlantic (26.7%), Pacific (10%), Prairies (10%), Ontario (6.7%), and Quebec (6.7%) (Fig. S6).

Interagency expert participants represented 13 agencies and organizations, including four federal agencies with interests in HPAIV (Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), Public Health Agency of Canada, Indigenous Services Canada, and Parks Canada). Eight provincial governments were represented, including British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, as well as academic experts via the CWHC. Notably, there were no respondents in the interagency group that identified as northern, although the nationwide selection may include people that represent northern interests and programs in addition to other areas (Fig. S6).

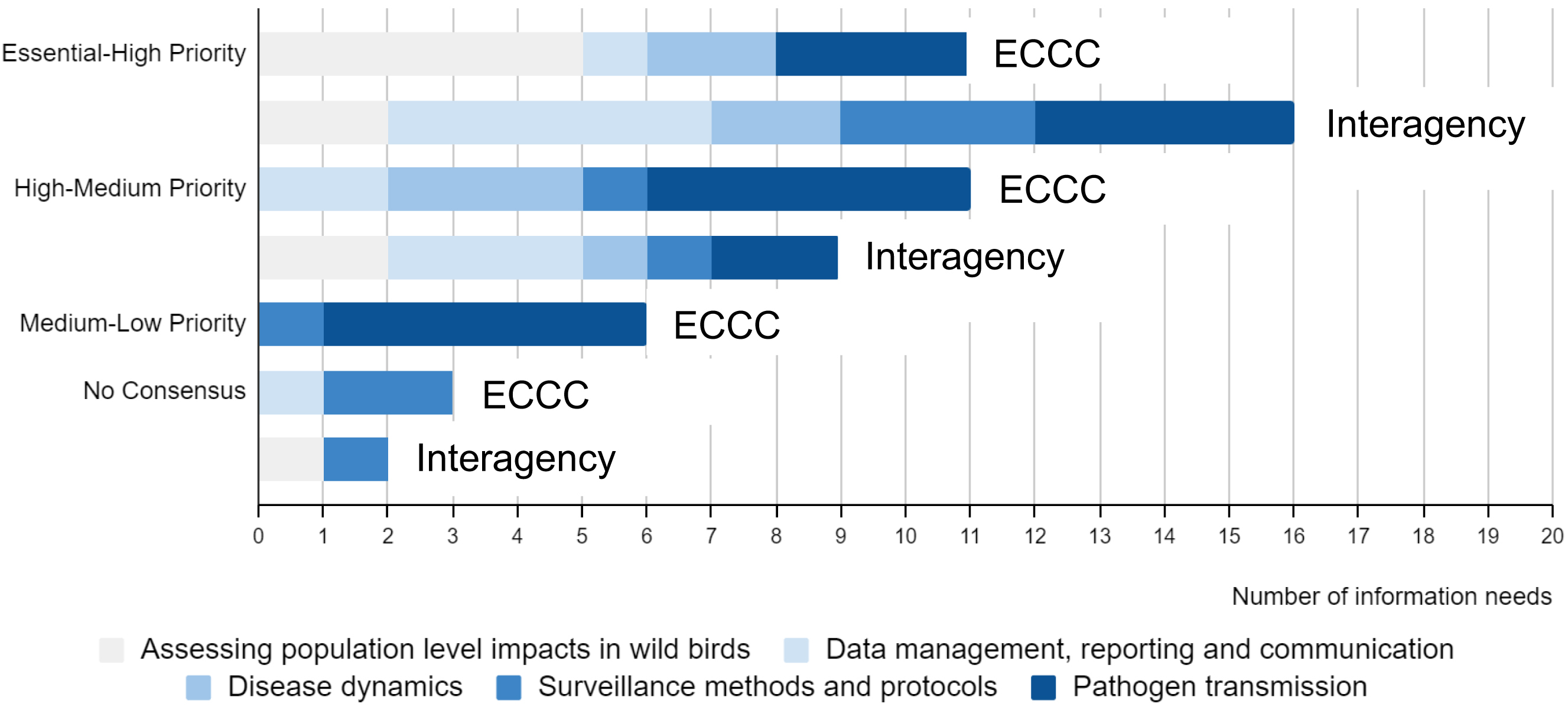

Prioritizing HPAIV-related information needs (Obj. 1)

Information needs reached the highest level of consensus when two adjacent categories on the Likert scale were considered together, thus no information need remained at a single category consensus. From this, we can infer that there was not much polarization in expert opinion regarding item priority levels. ECCC participants considered an equal number of information needs to be Essential–High (E-H) priority and High–Medium (H-M) priority, although overall, the consensus level was higher for the E-H priorities (

Table 2). We also found that no information needs identified were L-NP priority at any consensus level, which is not surprising given that this was a curated list of information needs developed by the ECCC Core team. Initially in the ECCC survey, a total of five information needs did not meet consensus on any level. After Workshop 1, in which participants considered their colleagues’ written rating justifications from the survey for “no consensus” items and re-rated them, three (9.7%) still lacked consensus (

Table 2).

Overall, the interagency respondents rated 59% of the information needs to span E-H priority (at any consensus level), and most of the remaining needs (33%) to be of H-M priority (

Table 3). The only item to reach a high level of consensus spanning the E-H categories was a need exclusive to the interagency survey, a “Harmonized regional and stakeholder reporting of wild bird AIV surveillance data”. The two needs, “Development of strategic recommendations on how to prioritize sample collections (e.g., when are full necropsies recommended vs. swabs vs. serology?)” and “A better understanding of migratory bird species/populations in Canada susceptible to high mortality and morbidity rates” did not reach a clear consensus (

Table 3). As with the ECCC process, no information needs reached a single category consensus; all information needs that reached consensus spanned two categories adjacent to each other on the Likert scale and none were considered to be N-P priority at any consensus level. However, unlike the ECCC cohort, interagency participants did not consider any need to be of M-L priority, and thus comparatively rated their needs to be of higher priority overall (i.e., all at least H-M priority). Group conviction in the priority level ratings was comparable between cohorts; although 13% of the ECCC group's needs reached a high consensus level irrespective of priority level as opposed to about 11% of the needs in the interagency group, the interagency participants had more medium consensus needs when compared the ECCC group, which had an equal number of needs reach low or medium consensus (

Tables 2 and

3).

The ECCC and interagency groups’ information needs were organized by theme (

Fig. 2). Since the surveys were not identical and had a different amount of information needs under each theme, comparisons between groups at the theme level was not straightforward. However, there were some notable observations.

All five of the information needs under the theme of “Assessing population level impacts in wild birds” were considered of E-H priority for the ECCC group. As established E-H priorities, all the needs under this theme were carried over from the ECCC to the interagency survey where the interagency participants considered them to be less of a priority, collectively (

Fig. 2).

The interagency group rated their needs under several themes to be of higher priority when compared to the ECCC group including the themes of “Surveillance methods and protocols” and “Data management, reporting, and communication” (

Fig. 2). The interagency group also considered their needs under the “Pathogen transmission” theme to be of higher priority, generally; the interagency group had fewer needs (6) to rate than the ECCC group (13) but considered all of theirs to be of E-H or H-M priority, whereas the ECCC group were more divided. The ECCC group rated 38% of their “Pathogen transmission” information needs to be of M-L priority, and all were related to the evaluation of the effectiveness of several approaches in reducing the spread of HPAIV (i.e., pausing research, closing tourism to or scaring birds off colonies, pausing rehabilitation, and bird banding programs).

In terms of individual needs, of the 12 information needs that were common to both surveys, the ECCC group and the interagency cohort agreed on seven in terms of priority level (all E-H), and of those, three reached the same level of consensus between the groups (

Table 4).

Criteria to guide actions when multiple species are affected by HPAIV (Obj. 2)

The top five criteria that ECCC experts thought should guide disease surveillance and research when multiple species or populations are impacted by HPAIV included Species at Risk, species commonly harvested in the US and Canada, species that may pose risks to the commercial poultry industry, species for which Canada hosts at least 10% of the global population, and species likely to have suffered population impacts due to HPAIV in 2021–2022 (

Table 5). Given that some regions had very few respondents, regional differences among experts were difficult to establish, but there were some items of note. For example, the only unanimous criterion in the top five across regions was “Species likely to have suffered population impacts due to HPAIV in 2021–2022” with 79% of all ECCC respondents selecting this criterion. Notably, for northern region respondents, a top criterion included prioritizing species that pose human health risks to those with recognized and affirmed treaty rights, which did not factor in the top five overall or with any other regional group.

ECCC respondents had the opportunity to suggest criteria beyond the predetermined criteria choices in the survey via an open-ended prompt (Table S1, Q13). Suggestions included non-listed species undergoing or recently experiencing population declines that threaten conservation or viability, Indigenous Government-identified priority species, species for which actions to mitigate spread or impacts of HPAIV would be easily or moderately easily implemented (e.g., species where recreational or scientific activities are taking place in or around the colony) and species that demonstrate behaviour that increases transmission risk.

The interagency survey showed that the most popular criteria to guide surveillance beyond 2022–2023 was to focus on species known to be asymptomatic carriers that drive large-scale transmission and spread. In total, 77% of the interagency respondents selected this criterion in their top five, which was not reflected in ECCC's top five criteria (

Table 5). By comparison, this criterion ranked 8th in the ECCC online survey. Overall, three of the top five criteria from the ECCC survey were also in the top five criteria for the interagency survey. This included species where population level impacts were likely, species that post a risk to commercial species, and those commonly harvested. Notably, species that pose a risk to human health were also included in the interagency top five, whereas this was 7th on the ECCC ranking. Interagency participants’ additional criteria suggestions included prioritizing surveillance during periods where there are juvenile birds in the population that are immunologically naive and vulnerable to mortality in susceptible species or populations. Also suggested was to prioritize Arctic nesting colonial species or provincial populations of an avian species listed under a provincial Species at Risk Act, among other criteria.

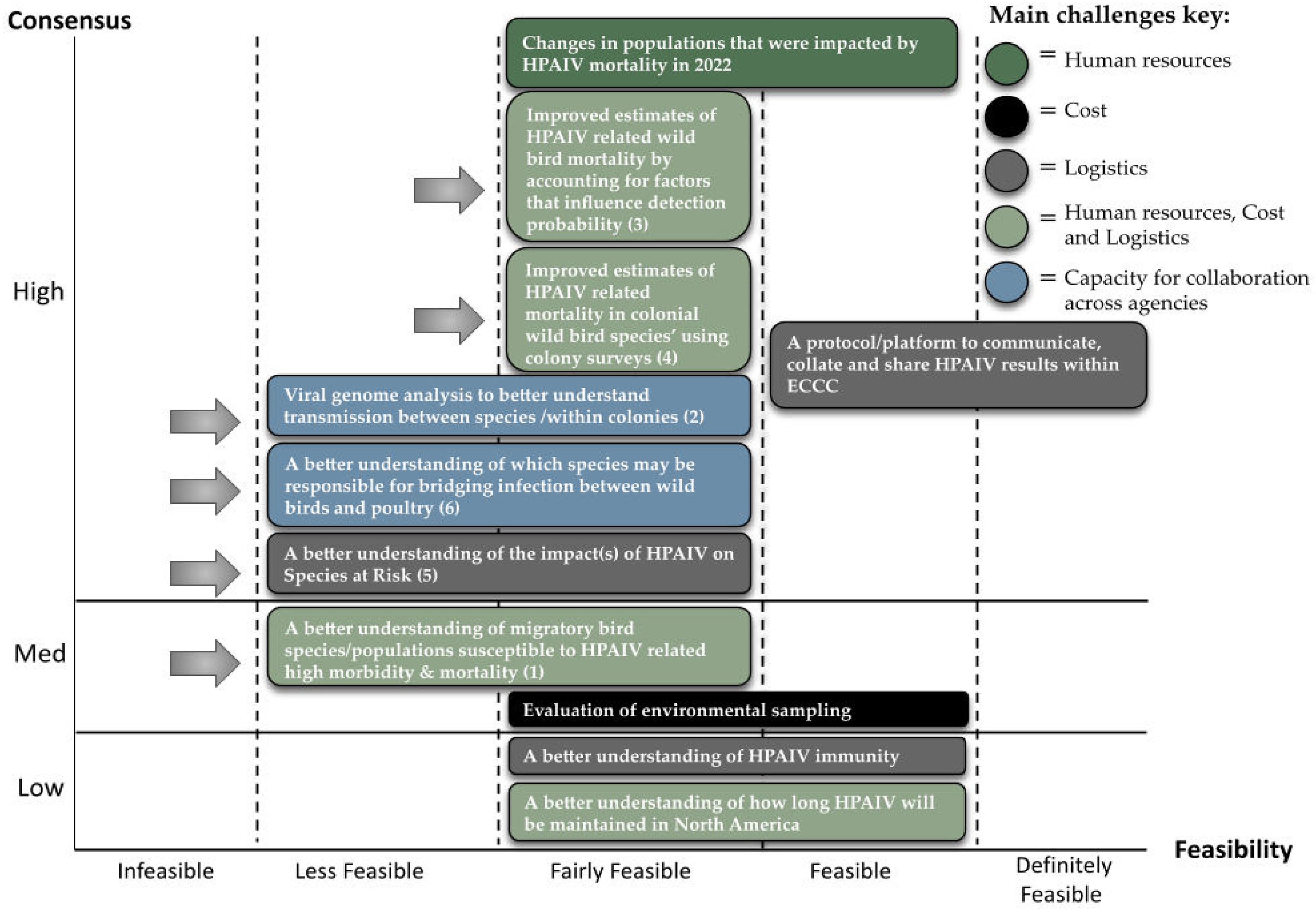

Feasibility of meeting ECCC top priority information needs and leverage points for progress; establish relative importance of highest priority under-resourced needs (Workshops 2–5)

During Workshops 2, 3, 4, and 5, the ECCC group further explored the feasibility of meeting the 22 most highly prioritized information needs to better understand resource needs within existing programs. The aim was to determine not only the main challenges in meeting needs but helping the group triage top needs based on the amount of support they required and establish the importance of the E-H needs that were considered under-resourced relative to one another according to the group.

Figure 3 and Supplementary material Fig. S7 (E-H and H-M needs, respectively) show a synthesis of the data gathered from the ECCC survey and Workshops 1–4 to meet Objectives 1 and 3. Eight E-H and H-M needs were rated either to be Feasible–Fairly feasible (F-FF), Feasible (F), or Definitely feasible–Feasible (DF-F). Although four of the needs did not reach consensus on perceived feasibility (all at the H-M level), none of the remainder were considered solidly DF or Infeasible (I), meaning the group considered the majority of the needs to be capable of being accomplished within a reasonable period of time pending varying degrees of additional resources/support. According to participants, the main challenges to meeting most of the relatively lower feasibility E-H needs (indicated by arrows in

Fig. 3) included logistical challenges often in combination with human resource limitations and financial constraints (

Fig. 3). When Workshop 4 participants ranked the six lower feasibility E-H needs based on relative importance in the face of insufficient resources, the top ranked “A better understanding of migratory bird species/populations in Canada susceptible to high mortality and morbidity rates” required an influx of resources on multiple fronts (

Fig. 3). Participants stressed the need for increasing capacity for collaboration with agencies outside of ECCC (sticky notes placed under the “Other” category in Google Jamboard) as a forefront challenge in fulfilling two E-H needs, including the second-ranked “Viral genome analysis to better understand transmission between species and within colonies”. Logistical challenges were heavily implicated as challenges to progress for the lower feasibility H-M needs (Fig. S7). We found that the leverage point for the majority of the E-H needs were in the program area of field needs, or field needs in combination with modelling capacity (Table S3).

Discussion

To prioritize research and monitoring activities related to HPAIV, the expert opinion process outlined here was carried out over the course of 6 months. The process engaged 65 staff members from across two branches within ECCC (CWS and STB) and an additional 28 experts from a total of 13 agencies/organizations. A subset of ECCC participants ranging from 25%–40% of the survey respondent group attended any one of the five online workshops, which was deemed as good representation given the workload and scheduling demand during this time. Overall, we had representation from all ECCC regions as well as a range of expertise and levels of experience with the AIV file.

Coding information needs into five themes helped shape a comparative understanding of priorities between ECCC and interagency partners. For example, the needs that reached consensus for ECCC under the themes of “Data management, reporting, and communication” and “Surveillance methods and protocols” are of lower priority when compared with the other themes and when compared with the interagency group ratings for those same themes. According to the justifications provided for the ECCC ratings in the survey, this is mostly because participants view them as largely in place and functioning sufficiently. For the interagency group, “Harmonized regional and national stakeholder reporting of wild bird AIV surveillance data”, “Improved protocols/platforms (e.g., dashboards, flowcharts) that communicate HPAIV results among federal, provincial, territorial, municipal, Indigenous partners, and other non-public stakeholders”, and the capacity to expand surveillance to other wildlife species, like mammals were of utmost importance. Additionally, given varying surveillance goals and changing viral ecology in wild birds, the interagency group considers a formalized, structured and collaborative process across partners to evaluate the optimal combination of surveillance methodologies to be a pressing need. The results indicate that greater emphasis should be placed on data and communications coordination across partners—a central tenet of One Health programs.

Needs associated with the theme of “Assessing population level impacts” were the most highly prioritized by the ECCC participants with several of the needs also achieving high group consensus thus distinguishing them from needs under other themes. Closing these knowledge gaps is vital to fulfilling ECCC's mandate of conserving migratory bird populations and key to informing their management (e.g., hunting regulations, impacts to subsistence/traditional harvest, visits to colonies). Participants' strong connection to this mandate and related commitments is evidenced by some of the rating justifications, which mention the Migratory Bird Convention Act, the Migratory Bird Treaty, and the fact that aspects of these information needs were identified already as critical work through other internal processes. From an efficiency perspective, experts also mention that work assessing impacts is a key step to preventing high regulatory burden for SARA-listed species. The interagency group's results echoed ECCC's for two of these needs, including the need for knowledge about the impact of HPAIV on Species at Risk as well as understanding the impacts on populations that experienced HPAIV-related mortality in 2022. According to ECCC experts, a fair-significant amount of resources channeled primarily toward the areas of logistics and coordination are required if we are to advance our knowledge on the HPAIV impacts on Species at Risk. For example, coordinating with provincial and territorial environmental agencies and Parks Canada to access and monitor populations in Important Bird Areas is required. Evaluating changes in populations that experienced HPAIV-related mortality in 2022 is one of ECCC's most important needs and was determined to require a minor to fair amount of resources mainly as human resource investment in key program areas.

“Understanding and reducing pathogen transmission” as a theme generated by far the most unique information needs for the ECCC cohort (13). Top priority needs under this theme that were also top priority for the interagency group include viral genome analysis, knowledge of which species may be responsible for bridging infection between wild birds and poultry in biosecure facilities, and the need to evaluate environmental sampling techniques that can monitor presence/absence of HPAIV at sites. To prioritize virtual genome analysis and identifying bridge species, a fair to significant amount of resources directed either toward collaborative planning or in providing analytical/lab capacity is required. Partnerships are also important. For example, since research related to bridge species requires the testing of migratory birds on agricultural landscapes, collaboration with the CFIA as well as provincial agricultural agencies would facilitate permissions to access for capture and sample collection. Viral genome analysis requires planning and implementing bird sampling at the national level and also requires CFIA support. The main challenge in evaluating monitoring techniques is the cost due to the resources needed to process samples. However, experts also pointed out that environmental sampling of feces, sediment, and water alongside migratory bird sampling around sites that are known to have been exposed to an HPAIV event also requires CFIA and provincial/territorial agency support. Based on these results, collaborative and joint work plans would appear essential to more fully understand pathogens.

After the expert opinion process, the results from this exercise were used to select and prioritize research and monitoring actions in 2023. More specifically, the results informed the multimonth planning process for fieldwork for 2023 as many of the top priority information needs that could be addressed within ECCC's existing operational scope were integrated into work plans. First, this was done by taking the top criteria results, and the priority information needs were used to assess swabbing opportunities that were collected from across ECCC programs (

Table 5). The CWS Wildlife Health Unit (led by Brown) staff collected information about the opportunities to sample birds in the 2023 field season, including species, locations, date, and potential sample sizes from staff across ECCC. These sampling opportunities were then scored against the criteria in

Table 5, and those that scored in at least one category were selected to proceed in 2023. It should be noted that many sampling opportunities scored in multiple criteria from

Table 5 and were recognized as of high priority as they addressed several research objectives.

Additionally, the priority needs identified were used to identify additional sample types that would need to be added to field collection protocols (e.g., blood and egg collection). For example, as a part of addressing the information needs relating to understanding immunity, ECCC staff piggybacked on existing seabird egg collection programs to subsample hundreds of eggs from a suite of species across eastern and central Canada. Efforts to build laboratory capacity to test these samples was also needed. In response, ECCC developed in-house capacity for AIV serologic testing, including method and sample type validation, in collaboration with CFIA. Therefore, results from this prioritization exercise produced short-term actionable recommendations that were able to be incorporated into surveillance field plans in the same fiscal planning year, and identified specific program areas requiring additional investment in field and lab capacity.

We do note that the sample size of the participants does limit the type and interpretation of results yielded by the process. We made an effort to include participants working in a variety of program areas and with differing expertise to ensure a robust and comprehensive approach to the generation and evaluation of information needs. However, we were not able to statistically evaluate differences between groups. More survey participants (ideally over 50) would allow for the use of different statistical methods that may highlight differences in priorities depending on location or organizational role. Additional participants during Workshop 1, in which participants re-rated “no consensus items”, would have been especially illuminating given that several participants changed their ratings when presented with justifications from their colleagues. While anecdotal, the change suggests that experts updated their thinking based on this systematic way of facilitating an exchange of ideas. Still, it is necessary to strike a balance between maximizing sample size and producing results within a timeframe appropriate to inform planning. Although a formal evaluation of the process did not take place, results were considered useful by ECCC decision-makers to develop work plans appropriate to address high priority information needs, identifying under-resourced areas and establishing shared priorities within a One Health landscape.

Of longer term interest was the value of the process itself as a systematic and informed approach that can be used at regular intervals across wildlife health programs to collaboratively identify and prioritize information needs (see Supplemental material for generalized workflow map, S8). Below, we discuss the results and their implications for planning and policy making. An important aspect of this process to consider for large organizations such as ECCC is that even within departments there may be different groups with different mandates and priorities related to an emerging One Health issue like HPAIV, and that have different management and reporting structures. When large organizations are considered as one entity, with monolithic perspectives, there will be missing critical points of view. Given that interagency dialogue and information sharing are key One Health priorities, it is important to ensure that the right suite of expertise is engaged within and across organizations.

A One Health approach asks us to consider not just a multisectoral approach but also careful consideration of the research to policy cycle ensuring that the project output can inform planning and decision-making. To do so involves incorporating policy informing endpoints as part of the research objectives from the beginning, thus ensuring the link to the policy levers is enshrined in the process. As one of its strengths, the prioritization process used here ensured clear links to policy through the involvement of both on-the-ground experts and managers that are making decisions about responses to HPAIV in migratory birds. By involving managers and scientists in project updates and results-sharing throughout, multiple parties were able to learn together about the most urgent information needs, the knowledge gaps, the current lines of evidence, and resource gaps. The tight science-policy link ensured that decision-makers were not waiting for the final report to inform processes that were underway, but instead were able to integrate the group's knowledge and discussions in an ongoing way as decisions on emerging items were needed.

Applying a One Health lens aligns with several of Canada's international commitments, including at the G20 and the G7 forums (

WOAH 2021;

G7 Research Group 2022). Although lacking formalized One Health governance bodies or policy, the Canadian government is already applying a One Health lens to issues like SARS-CoV-2, chronic wasting disease, and avian influenza. A One Health approach describes the intersection of human, animal, and environmental health, including wildlife and their habitat, and aims to optimize health at all levels through the development of collaborative strategies to create long-term, sustainable solutions (

Infection Prevention and Control Canada (IPAC) no date). The operationalization of a One Health model can help build a strong evidence base for designing research programs and developing decision-making tools to evaluate and solve cross-sectoral problems (

Conrad et al. 2013). At the foundation of a One Health model is information exchange between partners

(Government of Canada 2021), a tenet critical for managing emerging and complex issues where much of the science has not yet been established or shared through typical research channels (e.g., peer-reviewed journals). Further, the creation of tools through collaborations among One Health partners can support scientifically sound decision-making when faced with quickly changing scenarios when there is often a lack of information available. Using a One Health lens prompts us to consider how pathogens interact with entire systems, with varying levels of direct and indirect impacts to animal, environmental, and human health. It also calls upon us to balance the risks of interventions across domains. This process and results described here demonstrate a model on how One Health processes can be implemented in a science program context.