Introduction

The escalating demand for global crop production has increased inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer usage from 10 and 4.4 Tg year

−1, respectively, to 102 and 20 Tg year

−1, from 1961 to 2021 (

FAO 2022). As the world’s population approaches the projected 9.7 billion milestone (

United Nations 2022), nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers required to support the expanding agricultural production is expected to increase up to 158 and 27 Tg year

−1 by 2050 (

FAO 2018;

Mogollón et al. 2018;

Nedelciu et al. 2020). While synthetic fertilizers provide essential nutrients for high crop yield, 55% of global nitrogen and 40% of phosphorus inputs are lost to the atmosphere through volatilization, or to ground and surface waters through leaching and runoff (

Bouwman et al. 2009;

Yadav et al. 2017;

Ros et al. 2020;

Zhang et al. 2021;

Zou et al. 2022). In certain regions of world such as Asia and Oceania, this loss can be as high as 70% due to variation in the quality and quantity of fertilizers applied, crop types, soil characteristics, and climatic conditions (

Bouwman et al. 2009;

Zhang et al. 2021).

Much of this nutrient flux is due to fertilizer run-off entering different water bodies, such as groundwater, streams, lakes, and coastal environments. This advective process will likely continue to escalate, potentially disrupting normal patterns of nutrient cycling and ecosystem stability (

Alexander et al. 2008;

Loewald and Ryan 2020;

Manning et al. 2020). Excessive nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus can increase the carrying capacity of primary producers in aquatic ecosystems, and this initial spike in algal growth will then increase the abundance of consumers, leading to amplified consumer-resource oscillation cycles, which we term variance-driven destabilization (

McCann et al. 2021). This irony that the initial increase in primary productivity could disrupt normal consumer-resource interactions and ultimately destabilize an ecosystem is named the paradox of enrichment (POE;

Rosenzweig 1971). In its most extreme form, violent oscillations could drive either consumers or their resources stochastically to extinction.

A number of experimental studies have supported the principle of POE (

Rosenzweig 1971;

Luckinbill 1973;

Veilleux 1979;

McCauley et al. 1999;

Fussmann et al. 2000;

Meyer et al. 2012;

Fryxell and Betini 2023;

Tadiri et al. 2024), but the complexity in natural food webs can often dampen the destabilizing effect of enrichment through a variety of mechanisms, including predator interference, spatial refugia, and the presence of inedible or unpalatable prey (

Otto et al. 2007;

Roy and Chattopadhyay 2007;

Rall et al. 2008;

Feng and Li 2015). In the case where consumers exhibit a varying degree of resource selectivity (

Tilman 1982;

McCauley and Murdoch 1990;

Fryxell and Lundberg 1994;

Murdoch et al. 1998;

Genkai-Kato and Yamamura 1999), elevated nutrient loading could shift competitive outcomes to favor cyanobacteria and other forms of less edible algae species, at the expense of highly edible forms of green algae (

Brooks et al. 2016;

Gobler et al. 2017;

Trainer et al. 2020), which we term mean-driven destabilization (

McCann et al. 2021). In its most extreme form, such mean-driven destabilization can present as competitive displacement, leading to the extinction of green algal species and creating incidence of harmful algal blooms. In Ontario (Canada), the number of confirmed cyanobacteria-dominated algal blooms has increased from less than 5 a year in 1999 to over 60 in 2019, 20 of which were recorded for the first time from new locations (

Favot et al. 2023).

While both Rosenzweig’s paradox of enrichment and Tilman’s competitive displacement theory offered meaningful predictions of how nutrient-driven ecosystem instability may arise from local processes, in most freshwater ecosystems; however, instability will also depend on the degree of coupling among local populations occurring across the watershed (

Delin and Landon 2002;

Loreau et al. 2003;

Gounand et al. 2014;

Gravel et al. 2016;

Laan and Fox 2020;

Ryser et al. 2021;

Green et al. 2023;

Tadiri et al. 2024). This is a critical extension, allowing one to evaluate the impact of enrichment-driven instability as nutrients accumulate across the landscape due to anthropogenic land modification and extreme precipitation events (

McCann et al. 2021;

Smithwick 2021;

Tadiri et al. 2024). Recent spatial nutrient transport theory integrating nutrient-stability theory with meta-ecosystem models (

McCann et al. 2021) predicts that downstream accumulation of nutrients and detritus due to fertilizer run-off can amplify both mean- and variance-driven destabilization at a great distance depending on consumers’ feeding preference. When the consumer species consume all resource species, accelerated oscillations in the abundance of resources and consumers will dominate. When the consumer species exhibit selective feeding behaviour and leave inedible species unconsumed, competitive exclusion will drive edible species to functional extinction.

While some empirical studies have provided circumstantial evidence consistent with predictions generated by spatial nutrient transport theory (

Delin and Landon 2002;

Diaz and Rosenberg 2008;

Murphy et al. 2019), controlled experimental studies are uncommon (

Laan and Fox 2020;

Tadiri et al. 2024). Here, we use time series data collected from an experimental

Daphnia-phytoplankton-nutrient model system to test for how different forms of enrichment-driven instability (paradox of enrichment and/or competitive displacement) in a simple three-node network.

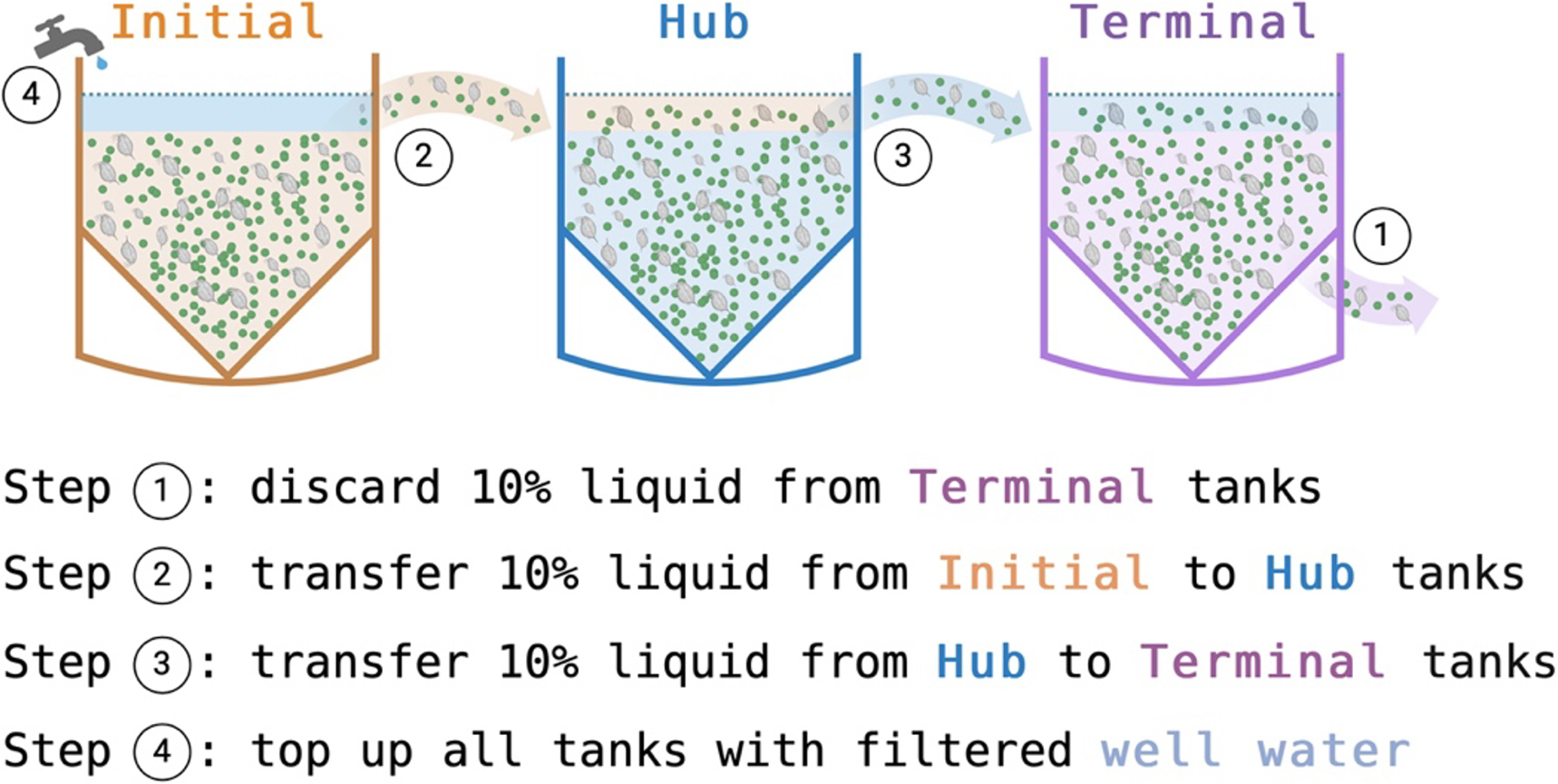

Results

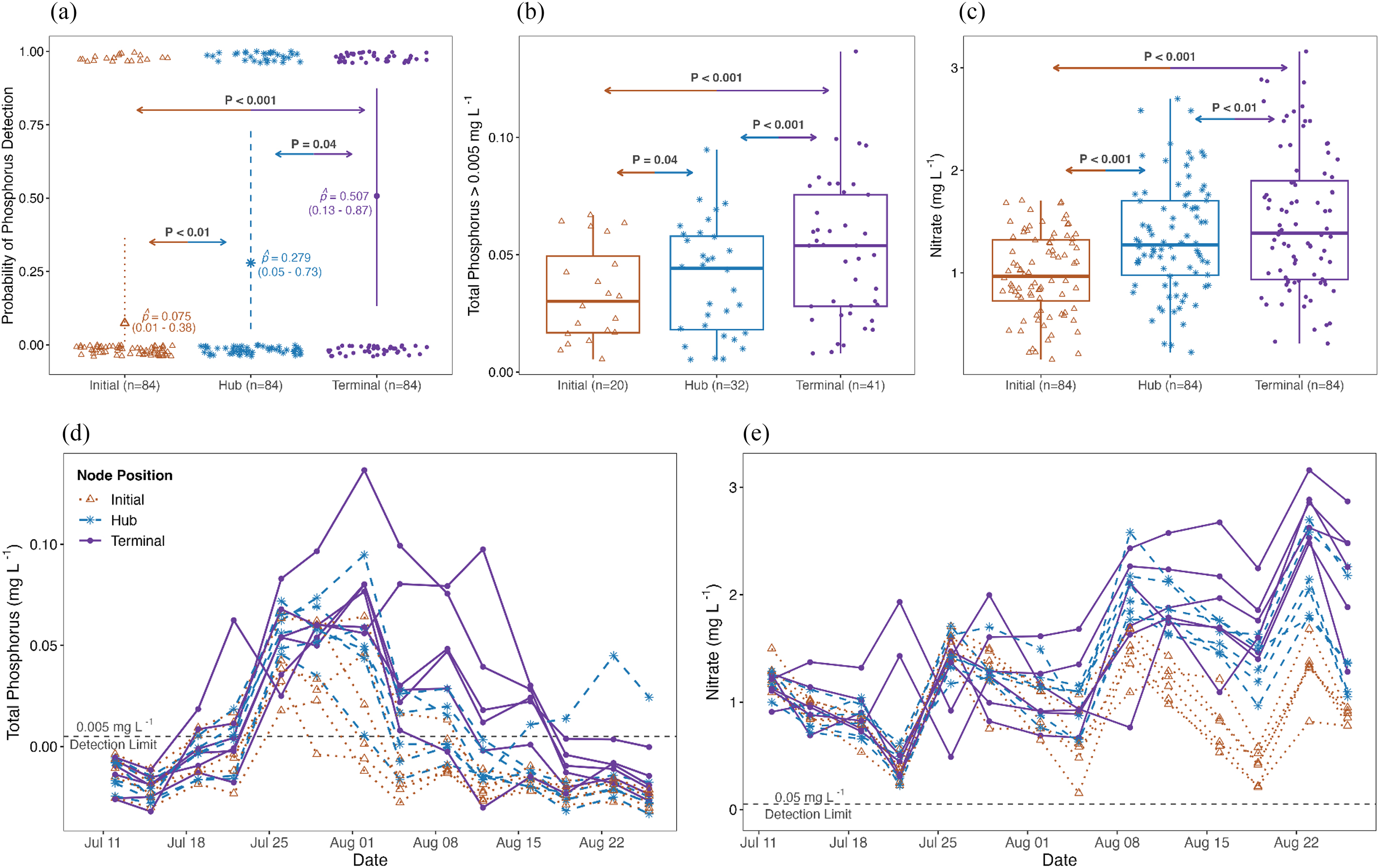

We compared the observed mean densities of nutrients, detritus load, green algae, cyanobacteria, and

D. magna across the initial, hub, and terminal nodes. Nutrients showed significant evidence of downstream accumulation consistent with predictions from spatial nutrient transport theory: terminal nodes had the highest detectability and concentration of total

P (p̂ = 0.51, CI = 0.13–0.87, Fig. 2

a; β = 0.05, CI = 0.03–0.06, Fig. 2

b;

Table 1) and

N on average (β = 1.50, CI = 1.26–1.74,

Fig. 2c,

Table 1), significantly higher than those of hub and initial nodes (

P < 0.05,

Table 1). We found that node position explained 15.4% and 13.6% of the variation in the observed mean total

P and total N concentration (

Table 1), while random effect of time and replication contributed to an additional 43% and 49% of the variation (conditional-marginal

R2;

Figs. 2d and

2e). This highlighted that spatiotemporal factors could contribute to as much as 62% of the observed variation in nutrient concentrations.

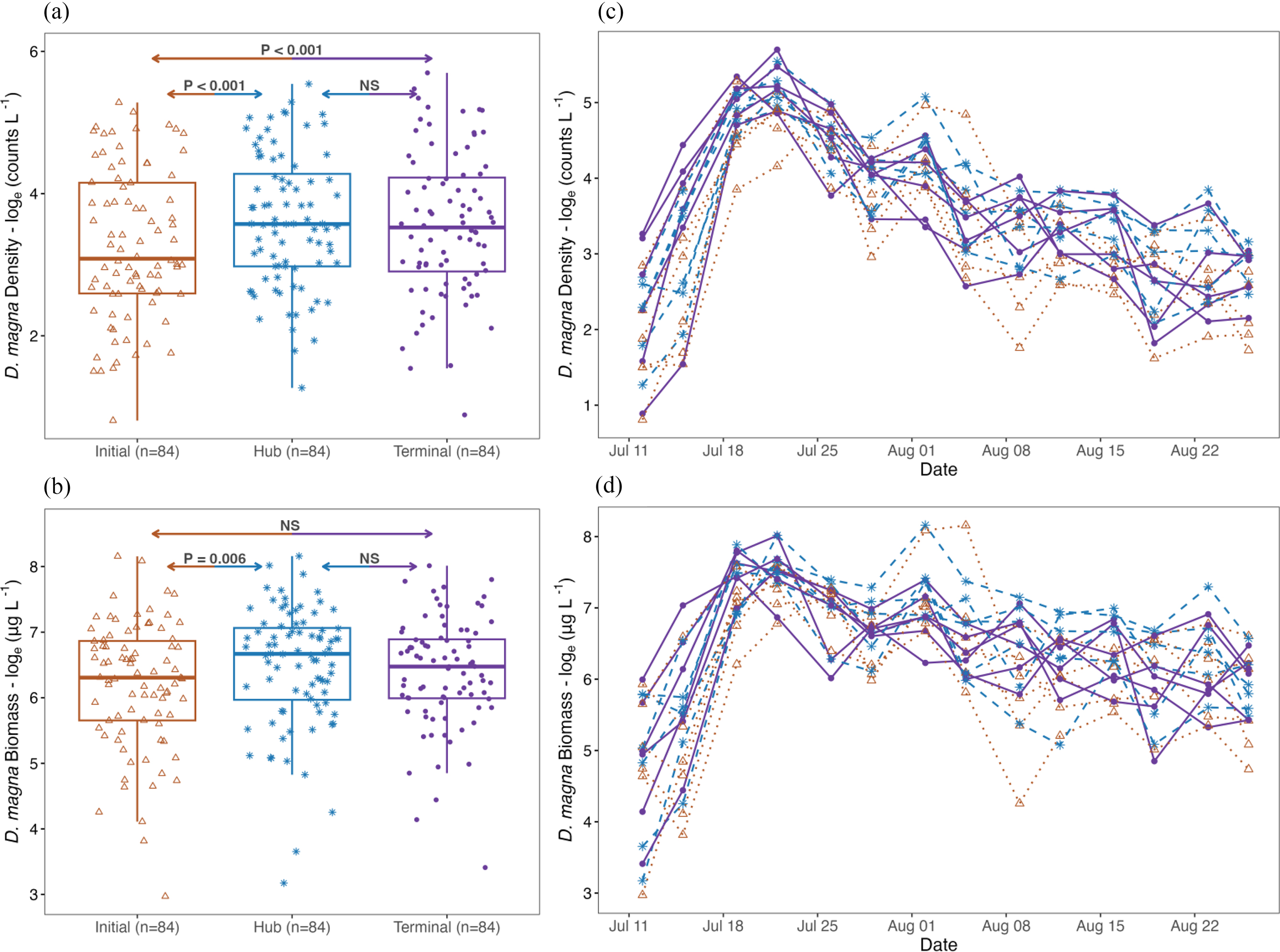

Increased levels of nutrients were associated with modest increases in the abundance of green algae and

D. magna in hub and terminal nodes relative to the initial node (

Figs. 3 and

4). While we found no difference between hub and terminal nodes (

P > 0.05,

Table 2), the initial node had the lowest densities of green algae (β = 15.48, CI = 15.19–15.77,

Table 2,

Fig. 3a),

D. magna (β = 3.26, CI = 2.78–3.73,

Table 2,

Fig. 3a), and

D. magna biomass (β = 7.48, CI = 7.09–7.88,

Table 2,

Fig. 3b). There was little evidence that cyanobacteria density responded to serial transfer, with no significant difference detected among initial, hub, or terminal nodes (

P > 0.05,

Table 2,

Fig. 3b).

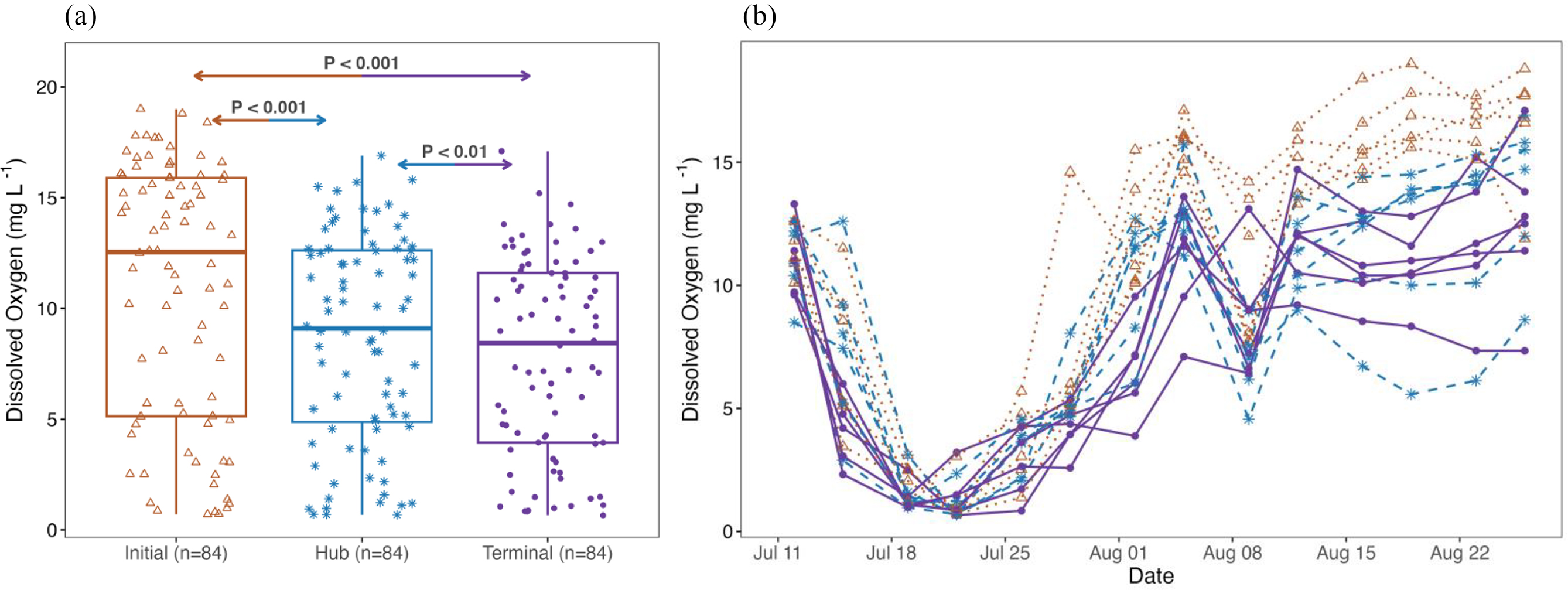

While we observed modest increase in algal and

D. magna density along the spatial gradient, we found strong evidence of reduced DO concentration downstream and recorded the lowest DO concentration in the terminal nodes (β = 7.80, CI = 5.40–10.20,

Table 1,

Fig. 5). Given that green algae and cyanobacterial cell density,

D. magna abundance, and detrital materials are all known to affect oxygen production and uptake, changes in DO concentration could be due to multiple causes. In our system where phytoplankton or zooplankton showed no difference between the hub and terminal nodes (

P > 0.05,

Table 2), we suggest that the decreasing DO was likely driven by increased detritus load and bacteria-driven oxygen uptake.

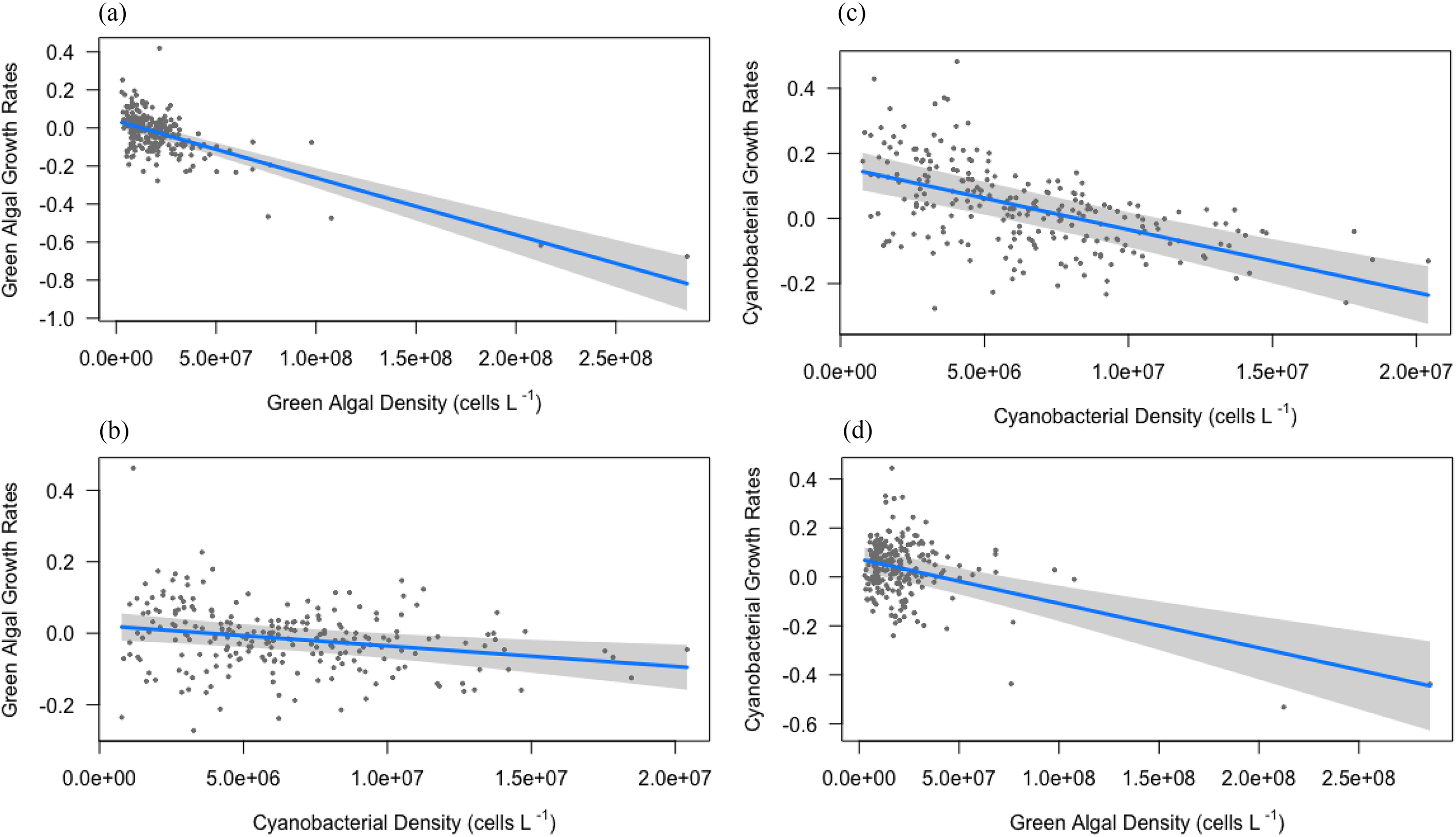

Tank position did not influence the exponential growth rates recorded for green algae or cyanobacteria (

P > 0.05, Table S1), but exponential growth rates within tanks consistently reflected localized effects of intra- and inter-specific competition (

Table 3). Green algal growth rate showed negative density dependence (

a1 = −3.00 × 10

−9, CI = (−3.52 – −2.47) × 10

−9,

P < 0.001,

Fig. 6a), and strong negative inter-specific competition with cyanobacteria (

b1 = −5.73 x10

−9, CI = (−9.59 – −1.88) × 10

−9,

P = 0.004,

Fig. 6c). Similarly, cyanobacterial growth rate decreased with cyanobacteria density (

a2 = −1.82 × 10

−9, CI = (−2.48 to −1.15) × 10

−9,

P < 0.001,

Fig. 6b) and green algae density (

b2 = −19.32 × 10

−9, CI = (−24.59 to −14.1) × 10

−9,

P < 0.001,

Fig. 6d).

D. magna growth rate demonstrated strong density dependence (

a3 = −0.0023, CI = −0.003 to −0.002,

P < 0.001,

Table 3) and a positive response to increasing green algae abundance (

b3 = 1.15 × 10

−9, CI = (0.34–1.95) × 10

−9,

P = 0.005,

Table 3), but no apparent relationship to cyanobacteria abundance. Abiotic factors such as total P, N, DO, and temperature had no detectable influence on exponential growth rates (

P > 0.05, Table S1).

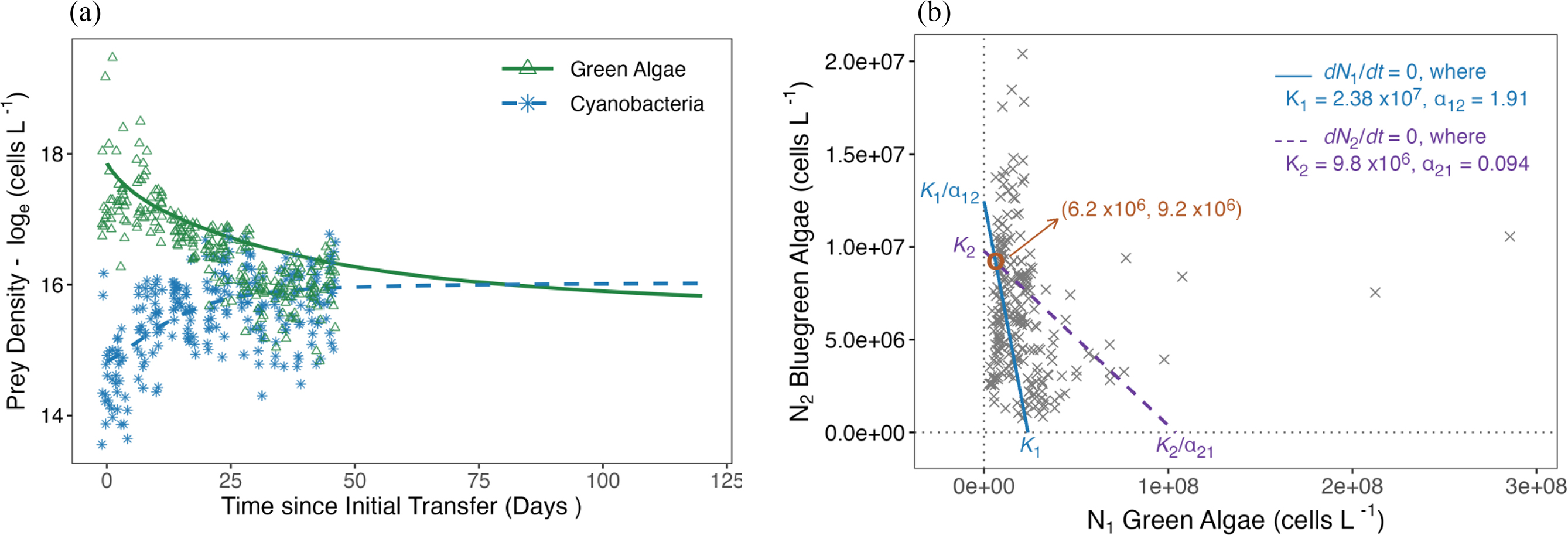

Coefficients of the Lotka–Volterra competition model suggest that even though cyanobacteria exhibited higher competitive inhibition on green algae than the converse (

α12 = 1.87 vs.

α21 = 0.094,

Table 4,

Fig. 7), stability analysis indicated a locally stable equilibrium with trajectories for both green algae and cyanobacteria converging on the interior intersection of their respective null isoclines (

Fig. 7b).

Discussion

From heavy usage of synthetic fertilizers and pesticide to large scale land clearing and modification, intense agricultural production is increasingly recognized as a key threat to aquatic ecosystem services (

Tilman 1999;

Dudley and Alexander 2017). Over half of nitrogen and phosphorus inputs from fertilizer application to farmlands can be lost to surrounding terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, destabilizing food web structure, interrupting nutrient cycling, and reducing ecosystem functions (

Bouwman et al. 2009;

Zou et al. 2022). In interconnected watersheds, nutrients can travel great distances, affecting many coupled ecosystems far from the source (

Loreau et al. 2003;

Gounand et al. 2014;

McCann et al. 2021;

Tadiri et al. 2024). To test the impact of nutrient transport on the presence and magnitude of enrichment-driven instabilities across a spatial gradient, we used the classic

Daphnia-phytoplankton-nutrient model system in a three-node unidirectional mesocosm experiment.

We found that even though nitrate, total phosphorus, and detrital materials accumulated significantly downstream (

Figs. 2 and

5), a pattern consistent with predictions from the spatial nutrient transport theory (

McCann et al. 2021), this did not result in extreme amplification of population abundance, cycling, or complete competitive exclusion of green algae in hub or terminal nodes (

Figs. 3c–

3d and

4c–

4d). Instead, our algal/cyanobacteria community converged on a stable equilibrium, where green algae and cyanobacteria co-exist at around 6.2, and 9.2 million cells L

−1, respectively, independent from node position (

Fig. 7b). Here, we discussed several factors at work in our system that could contribute to the stability in our system.

First, the enrichment level in our system could be inadequate. Given the detection limit of 0.005 mg P L

−1, we were only able to quantify total phosphorus in 37% of our total samples (

n = 92), 40% of which were below the blooming threshold of 0.03 mg L

−1 (n = 36,

Dodds et al. 2002). Even though we added liquid fertilizer weekly (∼15.8 mg P and 50 mg N Tank

−1), we found phosphorus uptake to be extremely rapid and that the phosphorus level sometimes dropped below the detection limit within 24 hours. Compared to the ideal 16:1 N:P ratio for algal growth, the exceedingly high stoichiometric ratio of N:P in our system (48:1 ± 43:1,

n = 92) suggested that phosphorus was the limiting nutrient in our system (

Guildford and Hecky 2000), which could lower algal growth rate (

Li et al. 2022) and reduce the potential for complete competitive exclusion (

Redfield 1934;

Takamura et al. 1992;

Neill 2005).

Second, strong intra- and inter-specific competition between green algae and cyanobacteria could be stabilizing. Previous work suggests that nutrient enrichment tends to amplify

Daphnia-phytoplankton prey-escape cycles most readily in simple systems composed of strictly edible algal species (

McCauley et al. 1999). In natural studies or experiments where less edible or unpalatable prey are present, enrichment rarely leads to prey-escape cycles (

McCauley and Murdoch 1990;

Murdoch et al. 1998;

Genkai-Kato and Yamamura 1999;

McCauley et al. 1999;

Mougi and Nishimura 2007), as a result of interspecific competition among algal prey (

Kretzschmar et al. 1993;

Genkai-Kato and Yamamura 1999) and/or changes in predator foraging (

McCauley et al. 1988,

1999;

Mougi and Nishimura 2007;

Yin et al. 2010). Similarly, we found that intra- and inter-specific competition between green algae and cyanobacteria were key factors influencing algal growth rates, but not

D. magna abundance (P > 0.05, Table S1). Cyanobacteria had higher maximum rates of increase (

r2 = 0.19 >

r1 = 0.071,

Table 4), suggesting they were more effective at nutrient uptake than green algae. Cyanobacteria exerted stronger evidence of competitive inhibition on the growth of green algae than vice versa (

α21 = 1.87 >

α12 = 0.094,

Table 4). While competitive displacement by cyanobacteria did not drive green algae to complete extinction (

McCann et al. 2021), it depressed long-term levels of green algal abundance to a considerable extent. Cyanobacteria reached a 50% higher density at equilibrium than green algae (9.2 × 10

6 cells L

−1 vs. 6.2 × 10

6 cells L

−1). This is particularly impressive in relation to the substantial difference in their respective carrying capacities (9.8 × 10

6 cells L

−1 vs. 2.38 × 10

7 cells L

−1).

Third, all our tanks were subject to augmented inoculations of green algae every two weeks, which could also contribute to the persistence of green algae in our system. We note that cyanobacteria slowly, and successfully, invaded our mesocosms 3 weeks after green algae density had already established population densities of 2.1 ± 1.2 × 10

5 cells L

−1. It is conceivable that algal competitive outcomes might change if initial levels of abundance or temperature conditions had been different. Slow rates of cyanobacteria invasion might be expected, because per capita growth rates of

M, aeruginosa are much lower at 18 °C than at 25 °C (

Shaw 2020), unlike green algae

C. vulgaris (

Jarvis et al. 2016).

Lastly, difference in prey palatability could influence

D. magna’s feeding behaviour. Our results showed that

D. magna population growth rates were positively related only to green algae abundance, and there was no detectable influence of cyanobacteria abundance. This suggested that while cyanobacteria in our system are edible, they were so poorly profitable that they failed to fulfill

D. magna’s energetic needs. Bench-top trials conducted in our lab were consistent with this hypothesis, showing that per capita rates of survival, reproduction, and individual mass gain by

D. magna declined with an increasing ratio of

M, aeruginosa to

C. vulgaris in their diet (

Shahmohamadloo et al. 2022). Interestingly, the lack of oscillatory predator-prey cycle from our experiment were consistent with predictions presented by Genkai-Kato and Yamamura using foraging theory (1999). In their predator-prey model, one predator could consume two prey species of varying profitability (

Figs. 1a-

4), and when the less palatable prey species approached the critical profitability threshold, oscillations were nearly muted. A similar theoretical prediction of behavioral stabilization comes from

Fryxell and Lundberg's (1994) consumer-resource models with optimal foraging by a single consumer species and two resource species, the least profitable of which is unable to sustain predators on its own. Prey escape cycles can also be muted by resource limitation (

Carroll et al. 2022;

Luckinbill 1973), complexity of natural food webs (

Rall et al. 2008;

Kretzschmar et al. 1993;

McCauley et al. 1999;

Mougi and Nishimura 2007;

Murdoch et al. 1998;

Persson et al. 2001;

Roy and Chattopadhyay 2007), landscape connectivity (

Feng and Li 2015;

Gounand et al. 2014;

Gravel et al. 2016;

Tadiri et al. 2024), behavioural plasticity (

McCauley and Murdoch 1990;

Mougi and Nishimura 2008), and rates of transport between interconnected ecosystems (

Gounand et al. 2014;

McCann et al. 2021).

There are some limitations to our study. It should be noted that our experimental design utilized a linear structure rather than a dendritic configuration (

McCann et al. 2021). We recognized that linear network would likely promote instability due to the lack of asynchronous input (

Anderson and Hayes 2018;

Tadiri et al. 2024), and we are cautious that the enrichment level in our system might not reflect the level of enrichment in natural riverine systems. Our system has two sources of enrichment: downstream accumulation from directional movement of water, nutrient, resource, consumers, and detritus, as well as weekly enrichment of fertilizers. Future work could explore how different enrichment level may interact with landscape configurations (linear vs. dendritic) to influence meta-ecosystem stability. Additionally, sexual production of ephippia in

Daphnia could influence consumer-resource dynamics (

McCauley et al. 1999), and would be worth further investigation. Finally, our experiment followed a seasonal temperature regime, coupled with a constant flow rate where all nodes had the same initial conditions. In natural environment, coupled ecosystems would exhibit a higher degree of heterogeneity of varying species composition and climatic condition, which could be another important aspect for future work.

Eutrophication from agriculture runoff remains a persistent and complex problem. As nutrients rapidly travel across coupled ecosystems via increasingly interconnected landscape (

Gravel et al. 2016;

Loreau et al. 2003;

McCann et al. 2021;

Smithwick 2021), it is essential to understand the effect and magnitude of nutrient transport on food web stability. Consistent with the recent spatial nutrient transport theory (

McCann et al. 2021), our

Daphnia-phytoplankton-nutrient model system provided evidence of strong nutrient and detritus accumulation downstream. However, these changes did not lead to an amplified

Daphnia-phytoplankton paradox cycle or complete competitive replacement of green algae by less edible cyanobacteria. Instead, our system converged on a stable coexisting equilibrium where cyanobacteria inhibited green algal growth and suppressed green algae abundance to a quarter of its normal carrying capacity. Improved stability in our system could result from nutrient limitation, prey competition and palatability, and weekly inoculation of green algae.