The between-day reliability of fasted circulating irisin concentrations: a cohort study

Abstract

Introduction

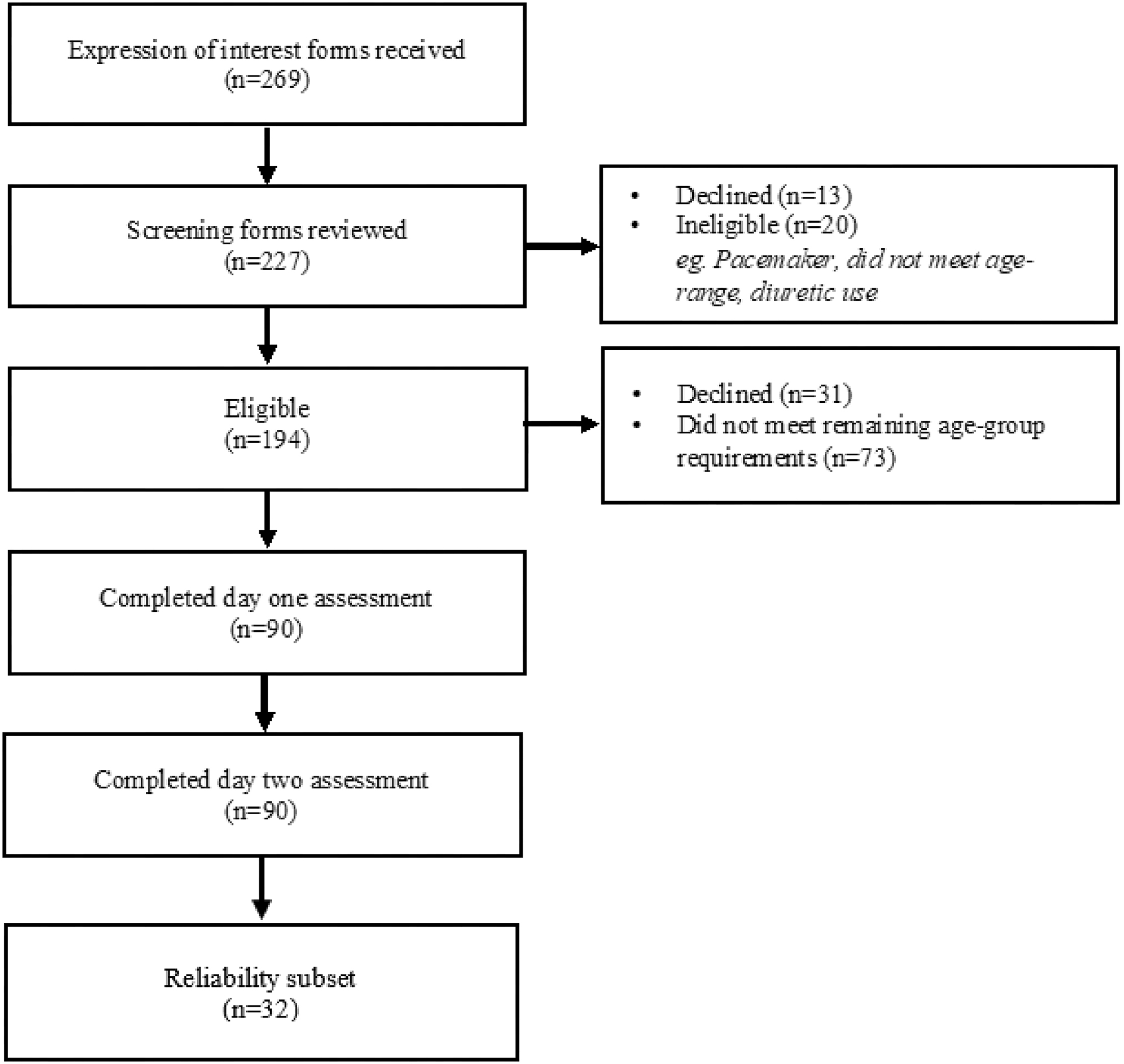

Methods and materials

Results

| Pooled | Age-groups | ANOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants | Young | Middle | Older | p | |

| n | 32 | 9 | 17 | 6 | – |

| % female | 53 | 67 | 53 | 34 | – |

| Age (years) | 47.8 ± 18.2 | 23.1 ± 3.4 | 52.4 ± 6.9 | 71.7 ± 4.7 | – |

| Body mass (kg) | 75.5 ± 15.7 | 74.3 ± 12.9 | 76.2 ± 18.3 | 74.9 ± 13.9 | 0.955 |

| Height (cm) | 171.0 ± 8.1 | 173.2 ± 9.3 | 170.3 ± 7.9 | 169.6 ± 6.4 | 0.627 |

| BMI (kg.m−2) | 25.8 ± 5.0 | 24.7 ± 3.2 | 26.3 ± 6.1 | 26.0 ± 4.2 | 0.750 |

| FFM (kg) | 47.6 ± 10.2 | 48.4 ± 11.3 | 47.1 ± 10.5 | 47.8 ± 9.3 | 0.958 |

| FM (kg) | 27.3 ± 10.9 | 25.3 ± 10.3 | 28.5 ± 12.4 | 26.7 ± 7.6 | 0.776 |

| BF% | 35.9 ± 9.2 | 34.1 ± 11.4 | 36.8 ± 9.2 | 35.8 ± 5.9 | 0.787 |

| Irisin (ng.mL−1) | 0.92 (0.96) | 0.86 (2.01) | 1.04 (1.06) | 0.62 (0.93) | 0.814 |

Note: Descriptive characteristics of pooled and age-group separated participant characteristics derived from the 4-compartment model, presented as mean ± SD, irisin presented as median and interquartile range. *Significant mean difference (p ≤ 0.05) via one-way ANOVA (parametric data) or Kruskal–Wallis (non-parametric data), FFM, fat-free mass, FM, fat mass, ng.mL−1: nanograms per millilitre.

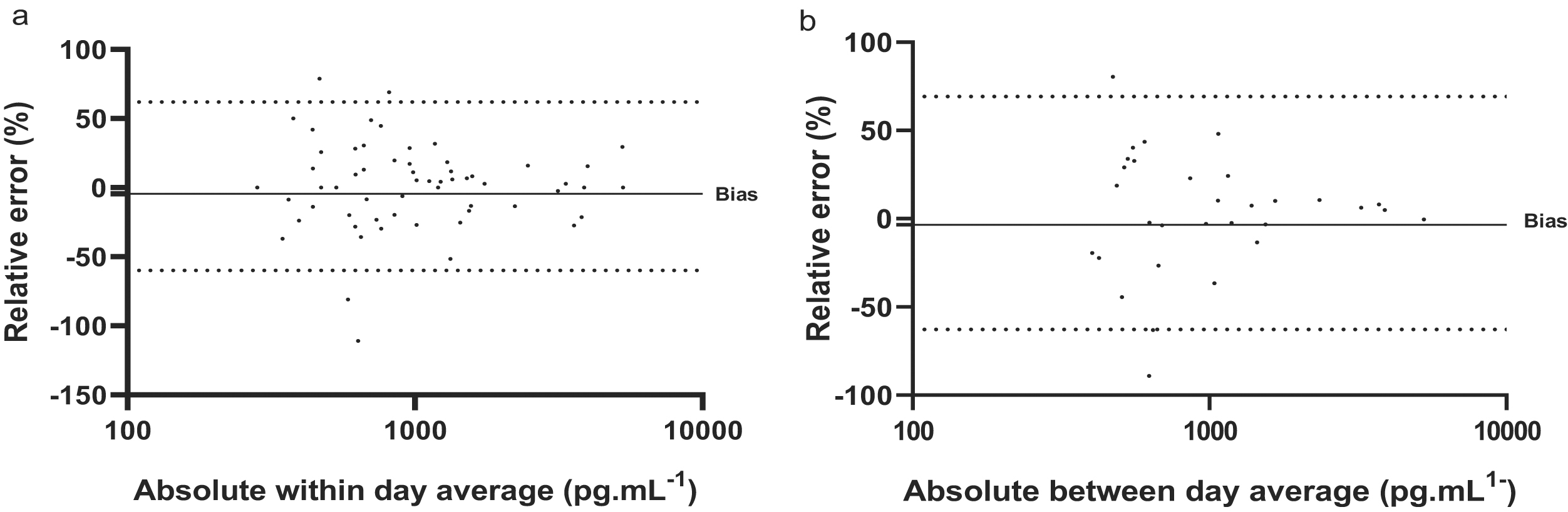

| Error type | Within-day | Between-day | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 32 | 32 | |

| Average valuesa (ng.mL−2) | Median | 0.93 | 0.92 |

| IQR | 1.02 | 0.96 | |

| Mean Δb | % of raw | 71.1 | 67.5 |

| Absolute | 0.66 | 0.62 | |

| 95% CIc | −1.07, 0.11 | −0.40, 1.35 | |

| TEEd | CV | 11.6 ± 10.9 | 12.7 ± 11.3 |

| ICCe | r | 0.927 | 0.963 |

| Proportional Bias | r | 0.133 | 0.221 |

| p | 0.302 | 0.201 | |

| Sexf | r | – | 0.012 |

| p | – | 0.948 | |

| Age | r | – | 0.053 |

| p | – | 0.795 | |

| Body composition | r | – | ≤0.158 |

| p | – | ≥0.875 | |

Discussion

References

Supplementary material

- Download

- 16.14 KB

- Download

- 26.81 KB

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Copyright

Data Availability Statement

Key Words

Sections

Subjects

Plain Language Summary

Authors

Author Contributions

Competing Interests

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Other Metrics

Citations

Cite As

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

There are no citations for this item