We set out to investigate the attributes of successful species recoveries in Canada. Our finding that 22% of the 36 sentinel species are now in a lower extinction risk category is consistent with what

ECCC (2023a) reports for all 530 species that have been reassessed (i.e., 20%). Surprisingly, however, we also found that only eight of 422 species (1.9%) with multiple COSEWIC assessments met our initial criteria for “success”: increasing abundance and decreasing extinction risk over time. This finding corroborates the limitations noted by

ECCC (2023a) and demonstrates that measuring change in extinction status only is an imprecise way to deduce whether population-level change in the wild is also happening concurrently.

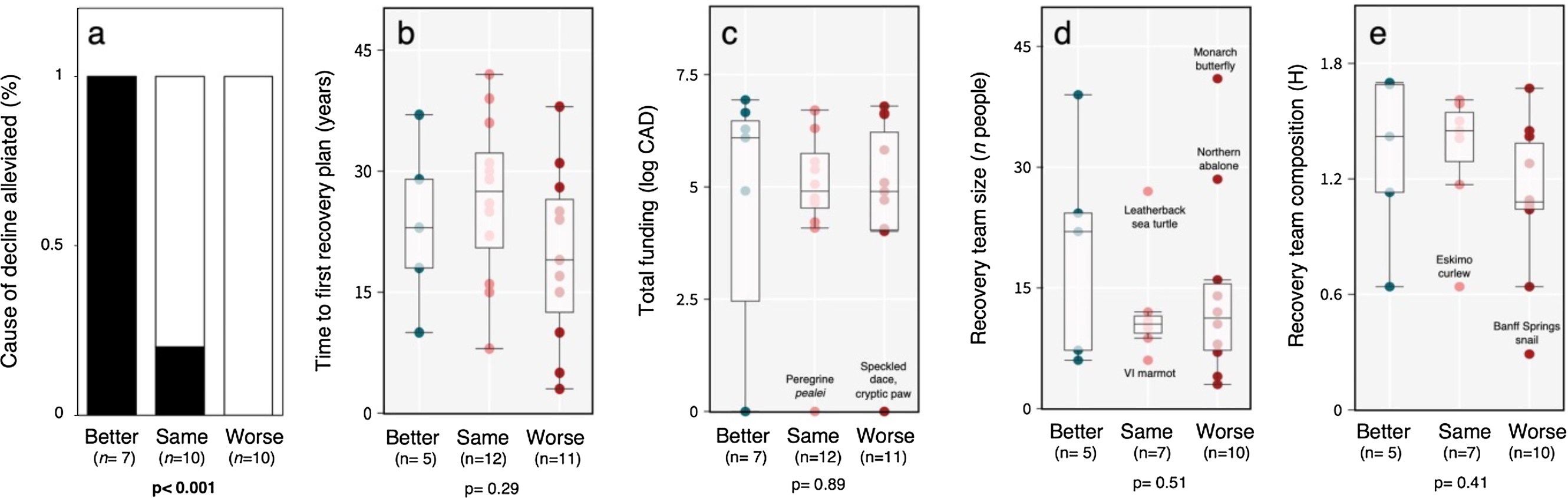

We found that the targeted alleviation of their initial causes of decline was the common thread that tied recovering species together, even when considering the personnel and financial resources invested. While it is perhaps unsurprising that alleviating the source of decline supports recovery, the relative rarity of this outcome was apparent across our historical analysis of sentinel species (

Table 1) and more recent case studies (

Table 2). It is important to acknowledge that for many successes, the original cause of decline was tangible, and could often be addressed through a singular targeted measure. As a result, during the first half of the 20th century, the primary approach to species recovery and conservation was through regulatory intervention, often to reduce overexploitation. For certain species with distributions extending into the United States (e.g., grey and humpback whales, Peregrine falcon), the prevailing American socio-political climate of the 1960–70s enabled widespread support for many environmental laws (including the ESA), which were seen as both effective and desirable (

Waples et al. 2013). Today, as wildlife populations are subject to cumulative anthropogenic pressures, action taken to address declines must also be considerate of this complexity, making both design and implementation exceedingly challenging relative to the past.

4.1. Identifying successful recovery pathways

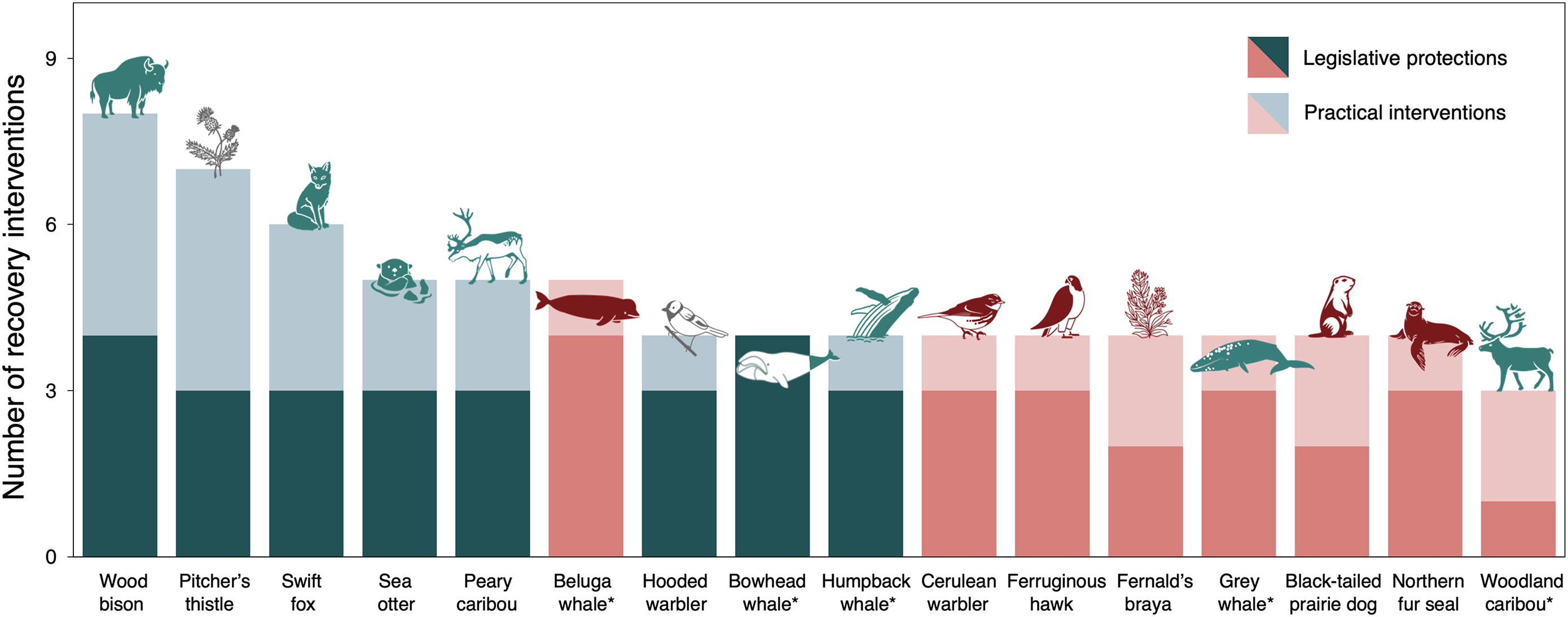

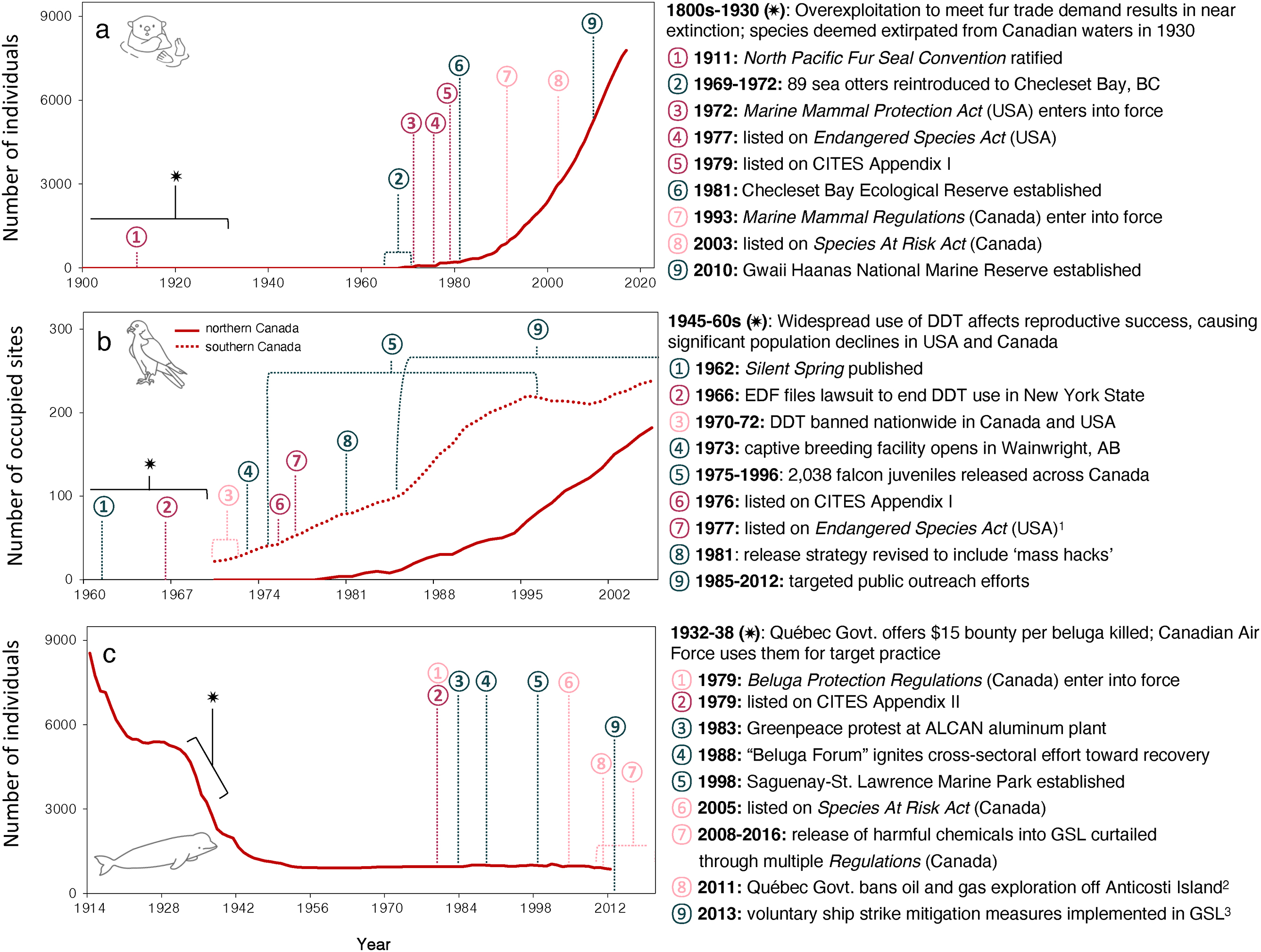

The onset of recovery efforts for some successes dates back over a century. And, in all cases, the most important first step was to

stop doing something harmful before

starting recovery interventions. We found that when laws and regulations were focused on alleviating direct, identifiable human threats and pressures, their implementation helped ensure the conditions necessary for successful recovery were met. Our findings are consistent with the results of

Ingeman et al. (2022), who show that the recovery of apex predators around the world is most significantly linked to the implementation of national legislation and international agreements that directly limit mortality. We also find that regulatory intervention was only the first step in rebuilding abundance and strategic applied approaches were also needed, especially for severely depleted or extirpated species such as the sea otter and swift fox. This finding is in keeping with work documenting the recovery of large carnivores in Europe, which showed that coordinated legislation to alleviate mortality from human–wildlife conflict across species’ ranges paved the way for these species to benefit from subsequent habitat restoration efforts (

Chapron et al. 2014).

Further, while reintroductions are not an option for all wildlife, we find they have helped increase abundance and decrease extinction risk for a diversity of birds and mammals in Canada following legislative protection and alleviation of their main cause of decline (e.g.,

Figs. 5a and

5b). Similarly,

Bolam et al. (2021) found that legislation, reintroductions, and ex situ conservation (e.g., captive breeding) are the interventions most likely to have prevented extinction for mammal populations around the world (with invasive species control, ex situ conservation, and habitat protection being the top preventative actions for birds). In Canada, reintroduction and other translocations are considered relevant for 38% of SARA-listed species (mostly plants), including Fernald’s braya (

Swan et al. 2018). Our results suggest that ensuring translocated wildlife enter an environment dissimilar to their current one (i.e., places with significantly reduced human disturbance) is likely critical for long-term success.

To this end, although we found significant differences in the number of interventions between successes and setbacks, our case study review shows that it is also the

quality as well as the

quantity of interventions that matters. This appears especially true for habitat protection. While most species had some degree of habitat protection, our case studies showed substantial variation in how much of a given species’ range or habitat type this included, whether sensitive life history areas were covered (e.g., breeding sites), and if the spatial protection also effectively mitigated human disturbance. Further, we found evidence of dedicated habitat restoration for only one species, the Pitcher’s thistle. Unlike protection, restoration requires perpetual maintenance and long-term monitoring of site characteristics to achieve outcomes related to habitat quality and the maintenance of associated ecological processes (

Ruiz-Jaen and Aide 2005). Focusing on restoration efforts to bolster existing spatial protections appears especially important for sedentary species, such the Fernald’s braya, which suffers from degraded habitat quality from recreational disturbances within (and adjacent to) areas designated to provide protection.

These observations are in keeping with past research showing that the primary threat for most species in Canada—habitat loss and degradation—has been insufficiently addressed for a large majority of threatened species (

Coristine and Kerr 2011;

Favaro et al. 2014;

Ray et al. 2021). Indeed, the benefit and efficacy of area-based conservation can also only be realized at-scale if protection in one place is not negated by development or habitat degradation in another. For migratory species, habitat protection in breeding or over-wintering locations appears especially important but often these areas fall outside of Canadian jurisdiction. One of the setbacks, the Cerulean warbler, exemplifies both challenges. This bird has been significantly impacted by the loss of old growth forests in southern Ontario and by logging, agriculture, and land development in the Andes—where it overwinters—with 60% of its habitat already lost by 2006 (

COSEWIC 2010).

4.2. Where to from here, Canada?

Although many threats related to overexploitation were historically addressed by targeted legislation, more diffuse threats—and their cumulative impacts—are harder to remedy. In June 2024, the Canadian federal government released its 2030 Nature Strategy which aims to ensure ecosystem-level action to halt and reverse biodiversity loss through an integrated, inclusive, adaptable, holistic evidenced-biased approach whereby all levels of government and social sectors are involved (

ECCC 2024). Based on our research we offer three main considerations as federal, provincial and territorial governments, businesses, and conservation leaders move toward achieving this vision.

First, to manage, restore, and conserve areas for enhancing species diversity and ecological processes (Targets 1, 2, and 3)—including the recovery of threatened species (Target 4)—we need an integrated approach that views the objectives of these Targets as synergistic and complementary rather than independent (

WCS 2024). We agree with the message highlighted repeatedly in the 2030 Nature Strategy (

ECCC 2024) that no single jurisdiction can protect threatened wildlife, and that restoration and conservation planning will need to embrace broader ecosystem restoration goals across all levels of government. In general, collaborations between municipal, provincial, and Indigenous governments continue to be well positioned—and have substantial power—when it comes to ensuring habitat restoration and protection since the Canadian federal government cannot achieve 30% protected area (Target 3) without assistance from other jurisdictions (

ECCC 2024).

Inconsistencies in provincial species-at-risk legislation and how it gets implemented need to be alleviated across jurisdictions (

Gordon et al. 2024). We also suggest that stronger bilateral action will be necessary to effectively protect transboundary species (i.e., species distributed across the Canada–US border), as well as other migratory species, and their associated ecosystems. This is especially important as many of these species are already endangered and suffer from the added impacts of climate change influencing their distribution (

O'Brien et al. 2022). Results from our case studies showed that consistency in US and Canadian legislation (e.g., concurrently prohibiting DDT), as well as joint efforts from American and Canadian recovery teams benefited multiple successes. To-date, however, transboundary collaboration has been limited for at-risk species and should be strengthened to ensure maximum efficacy of habitat protection and recovery interventions (

Olive 2014). At the other end of the spatial scale, thoughtful municipal spatial planning will also play a vital role in the coming years, especially since achieving both positive conservation and socio-economic outcomes from protected area establishment depends heavily on meaningful inclusion of local stakeholders (

Oldekop et al. 2016). As municipal governments work to meet the needs of growing human populations, so too must they strive to freeze their spatial footprint to prevent further loss of natural habitat while simultaneously restoring natural spaces adjacent to areas of high human density.

Second, for species that are endemic to Canada or lack the potential of a rescue effect, having strong domestic legislation combined with comprehensive on-the-ground interventions appears especially important. The original RENEW species recovery program was established to be “pan-Canadian” and cross-sectoral, to “establish a national programme for recovering wildlife at risk [that is] shared by all and not confined by territorial or provincial boundaries” (

RENEW 1989). While RENEW no longer exists, the Pan-Canadian approach was reinvigorated in 2018 to provide a cross-jurisdictional framework for the planning and operationalizing of multi-species and ecosystem-based conservation (

ECCC 2018). Notably, two successes in our study (Peary caribou and wood bison) were included in the first subset of six “priority species” identified for coordinated recovery through this initiative. The chosen priority species (four caribou, wood bison, and sage grouse) were selected largely for their cultural significance and most are distributed across higher latitudes in regions with low direct human impact (

ECCC 2023b). Yet, the Arctic (>66.5°N) is also warming faster than anywhere on Earth (

Rantanen et al. 2022) and industrial resource extraction is anticipated to increase throughout the region (

Hanaček et al. 2022). Since our findings show the importance of addressing both the underlying threat and ensuring environmental conditions are conducive to recovery, we emphasize that for the Pan-Canadian initiative to be successful long-term, reductions in greenhouse gas emissions combined with spatial efforts to ensure population connectivity and survival are required (

Mallory and Boyce 2019). Such measures could include, for example, prohibitions on all extractive activities in calving grounds and ice crossing corridors (

Kitikmeot Regional Wildlife Board 2016).

In addition to planning for climate-related threats, we note that ongoing extractive activities, development, and human disturbance (including in protected and conserved areas) continue to limit wildlife recovery, including for certain provincially listed at-risk species in our study (i.e., piping plover

melodus and Fernald’s braya). Three decades ago, Canadian species recovery documents emphasized that, “although development projects produce short-term economic benefits, a truly sustainable economy requires a healthy environment” (

RENEW 1994) and the private sector was viewed as an important stakeholder in helping achieve recovery targets (

RENEW 1990). Today, GBF Target 15 specifically asks businesses for better assessment and disclosure of dependencies and risks to biodiversity and private sector actors are explicitly called on to combine their “net zero” approach in the face of climate change with a “nature positive” approach to reduce biodiversity loss (

UNEP 2022). As such, there is a genuine opportunity for the private sector to invest in conservation and sustainable practices, especially for industries that rely on natural resources and are thus affected directly by biodiversity loss (

ECCC 2024).

Lastly, in keeping with GBF Target 21, we encourage further review of successful pathways leading to species recovery within Canada and stronger accountability when it comes to the outcomes associated with aspirational federal goals. Intention is the first step for establishing recovery documents and designating interventions but, as we found, intent alone does not guarantee the quality of an intervention or that recovery will occur. Thus, we suggest that not only measuring progress toward the implementation of the 2030 Nature Strategy objectives but also explicitly defining metrics to assess the outcomes of these objectives is a critical aspect of accountability missing from Canada’s recently proposed

Nature Accountability Act (Bill C-73, first reading 13 June 2024). Basic indicators such as changes in absolute population abundance, which we used here, could be useful in this regard (

Callaghan et al. 2024), but many other options to measure the effectiveness of conservation approaches have also been identified (

Westwood et al. 2014;

Geldmann et al. 2021).

Equally, while our study focused primarily on the outliers (i.e., best and worst cases), future work could attempt a more comprehensive analysis of ecological and socio-political attributes associated with all COSEWIC species. Such information could perhaps contribute to the new IUCN Green List (

Akçakaya et al. 2018) or equivalent national framework that more comprehensively defines and collates successful recovery interventions. Although species recovery teams no longer exist in the same way as in the past (i.e., the years of our sentinel species analysis) we also encourage a continued focus on understanding who is represented in species conservation in Canada, how relationships between different stakeholders and rightsholders evolve, and where meaningful ecosystem-focused conservation efforts can be applied in keeping with the many commitments made under the GBF. For example, we found that zoos and environmental NGOs have been prominent in ex-situ conservation (reintroduction and maintenance of genetic diversity) and the involvement of these institutions is likely to increase in light of the GBF, with calls for multi-scale coordination to foster the implementation of the GBF Targets (

Moss et al. 2023). Equally, many First Nations, Métis, and Inuit are already leading by example when it comes to species recovery in Canada (

Menzies et al. 2021;

Lamb et al. 2022;

Rachini 2023). Indeed, the recovery of culturally important wildlife is of critical importance to Indigenous communities who have legal and cultural ties to these species (

Lamb et al. 2023). Yet, as with many species and habitat protection efforts in North America over time (

Kantor 2007), the social, cultural, and economic impacts of successful sea otter and wood bison reintroductions discussed in our case studies demonstrate the complexity inherent in balancing the benefits to wildlife with the rights of people (Targets 9 and 22). As such, meaningful co-facilitation with affected rightsholders must remain a fundamental aspect of ethical conservation initiatives going forward. Conservation of species and spaces in Canada must support Reconciliation with Indigenous communities and not infringe on their aspirations to self-govern (

Zurba et al. 2019).

4.3. Recovery is a moving target: research limitations

While this work reviews some of the interventions and legal frameworks that have contributed to reversing species declines, we stress that our results highlight patterns and commonalities rather than direct causalities. As such, our findings are not meant to suggest that the interventions we discussed are the only pathways whereby recovery efforts could or should occur, nor that efforts lacking these elements will ultimately fail. Rather, we hope this work provides food for thought as part of a much larger conservation conversation, and the importance of reviewing and learning from successes—which are often outliers—as a critical part of planning to achieve biodiversity protection goals.

We intentionally chose to investigate all Canadian wildlife. However, the taxonomic diversity in our analysis made comparing interventions and outcomes challenging given inherent differences in life histories, scale and location of threats, and applicability of different conservation interventions. The primary analytical challenges we faced were the availability consistency of information for the species we reviewed. While our approach to analysing the two COSEWIC datasets was systematic, we did have to decide which setback species to retain for detailed analysis, which introduced some subjectivity and meant that certain taxonomic groups (e.g., fishes) were not included.

Unfortunately, not all wildlife in Canada have been assessed by COSEWIC, much less received multiple assessments. As we observed for multiple caribou species (see Supplementary Methods), a species’ risk status can change with new information, which can make comparisons between assessments challenging. Further, the classification of species into only three at-risk categories may also mask progress (or a lack thereof). For long-lived species with low fecundity and/or high age at maturity, noticeable population-level changes could take decades even under optimal environmental conditions and recovery efforts, while the high vulnerability of some species to catastrophic natural events may always preclude them from being listed as anything other than “Endangered” despite population increases (e.g., whooping crane, Banff Springs snail). The irregular release of COSEWIC assessments and recovery documents meant certain species were not included in the analysis and/or the trajectory of a species may have changed since its most recent assessment. For example, over half of sentinel species’ last COSEWIC assessments were conducted before 2014, which means information we obtained related to their “causes of decline” or “key threats” (

Table 1) is likely outdated in some cases. Equally, the RENEW funding data we used were available for only a subset of years and the substantial allocation of funds to some high-profile birds and mammals may be linked to the fact they were assessed decades before the first mosses and arthropods.

For the successes and setbacks, the asynchrony of COSEWIC assessments resulted in a relatively low sample size of species for investigation and, potentially, a mismatch between the information we used and what is currently happening in the wild for those we did investigate. We acknowledge that any attempt to quantify recovery will only ever capture a single snapshot in time and space and while COSEWIC assessments can provide important information on long-term trends, a de-listing should not be considered an endpoint for conservation interventions and monitoring. Rather, it is a single grade on a continuous report card.