Introduction

Climate and landscape change are altering the boreal forest at unprecedented rates (

Pimm et al. 1993;

Sala et al. 2000). Climate plays a significant role in determining vegetation growth rate (

Brecka et al. 2018), plant distribution (

Soja et al. 2007), and phenological timelines (

Post et al. 2018;

Park et al. 2020). Concurrently, the boreal forest is experiencing rapid rates of deforestation, primarily due to fire and forestry, but also fossil fuel extraction, surface mining, and agriculture (

Hansen et al. 2013;

Pickell et al. 2015). These disturbances convert mature forest into early-seral stands, altering the composition and productivity of the plant community (

Haeussler et al. 2002;

Sulla-Menashe et al. 2018). The effects of climate and landscape change have cascading impacts, including on herbivores who rely on these changing plant communities for nutrition (

Bradshaw et al. 2003;

Weisberg and Bugmann 2003). For example, the transition of mature forest to early-seral stands typically increases forage availability for ungulates during the summer (

Strong and Gates 2006;

Edenius et al. 2015;

Finnegan et al. 2019), although the effect varies according to silviculture treatments such as planting (

Boan et al. 2011), herbicide application (

Strong and Gates 2006;

Koetke et al. 2023), and removal or burning of woody material that remains after harvest (

Edenius et al. 2014).

Diet, or the ingestion of nutrients, is inherently important to understanding an animal’s nutritional ecology, including outcomes for reproduction and survival. However, it is difficult to quantify diet for many free-ranging species. Typical methods are expensive, invasive, or time-intensive (e.g.,

Hodder et al. 2013;

Thompson et al. 2015;

Denryter et al. 2017). Recent advancements in DNA metabarcoding have improved our ability to quantify diet items in pellet samples (

Pompanon et al. 2012;

Ando et al. 2020). DNA metabarcoding uses PCR amplification and high-throughput sequencing to identify the genetic signatures of plants and fungi (

de Sousa et al. 2019). In comparison to microhistology, metabarcoding can be more cost effective (

Nichols et al. 2015), less labour intensive (

King and Schoenecker 2019;

Littleford-Colquhoun et al. 2022), and can reveal greater taxonomic precision (

Port et al. 2016). However, there is still some uncertainty in establishing the relationship between quantifiable DNA fragments (i.e., read counts) and the biomass of the diet item that was consumed. There also are questions about sample age and viability and potential challenges associated with the resolution of the reference library when differentiating genetically similar diet items (

Bonin et al. 2020).

Woodland caribou (

Rangifer tarandus caribou), an ungulate found across Canada, are forage specialists during winter that feed primarily on terrestrial and arboreal lichens (

Thomas et al. 1996). In comparison, moose (

Alces americanus), deer (

Odocoileus spp.), and elk, sympatric ungulates found across much of the range of caribou, are more generalist foragers (

Franzmann and Schwartz 1997). Moose consume over 200 species, although willow (

Salix spp.) and birch (

Betula spp.) are common forage items across much of the North American range of the species (

Franzmann and Schwartz 1997). In Alberta, the winter diet of moose is dominated by trees and shrubs (

Nowlin 1978;

Renecker and Hudson 1986,

1988). To the best of our knowledge, the diet of white-tailed deer (

Odocoileus virginianus) has not yet been evaluated in western North America. In other regions, white-tailed deer are known to have a varied diet including deciduous trees and shrubs, coniferous trees, forbs, grasses, and fruits (

Hewitt 2011). During winter, mule deer consume true firs (

Abies spp.) and Douglas fir (

Pseudotsuga menziesii), deciduous shrubs, and various forbs (

Williams et al. 1980;

Hodder et al. 2013;

Rea et al. 2017). In general, elk consume grasses (

Holsworth 1960;

Woods 1972;

Salter and Hudson 1980;

Churchill 1982;

Kohl et al. 2012), however, forbs, shrubs, sedges, and ground litter also are common diet items (

Holsworth 1960;

Woods 1972;

Salter and Hudson 1980;

Churchill 1982). A few studies found trace amounts of conifers and mosses in the winter diet of elk (

Woods 1972;

Churchill 1982;

Kohl et al. 2012).

Despite the importance of forage for an animal’s ecology, there are few recent studies of the diet of sympatric ungulates in western Canada. We used metabarcoding of pellet samples to identify the winter diets of deer, moose, elk, and caribou found across west-central Alberta. Similarities and differences among diets indicate potential niche overlap that may lead to competitive exclusion. This is particularly significant for understanding the predator-prey dynamics of woodland caribou, an Endangered species in much of western Canada, and for understanding apparent competition (

DeCesare et al. 2010), where forage subsidies are hypothesized to be attracting other prey species into caribou ranges (

Fisher and Burton 2021;

Fuller et al. 2023).

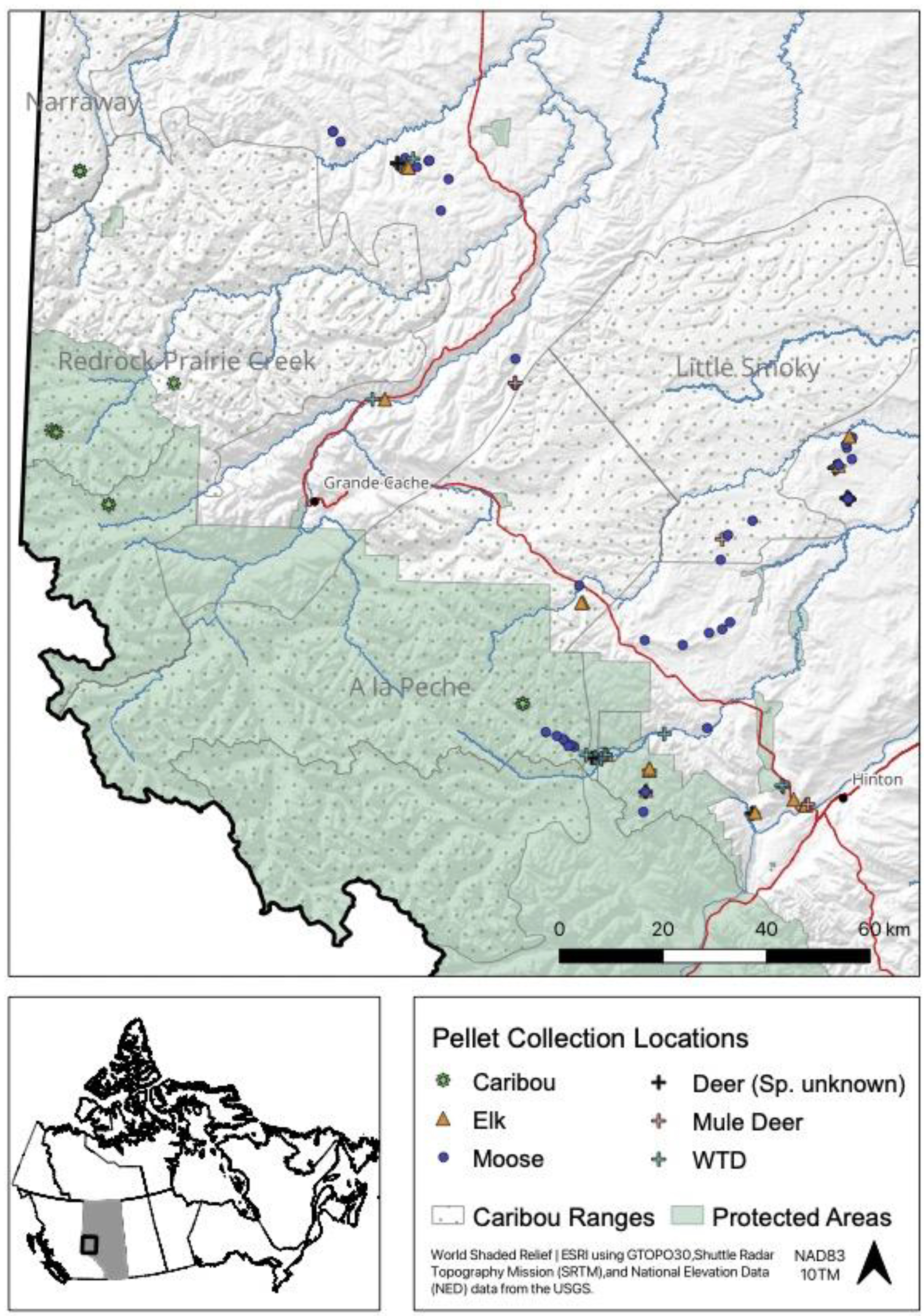

Results

We submitted 88 samples for metabarcoding analysis that were collected from 88 discrete sites (Supplemental Table 1). In most cases, sampled pellet groups were >500 m apart (N = 46), however, some groups were within 100 m (N = 14) of another pellet group, but from a discrete or unique trail in the snow. We used genetic analyses to identify the deer species of 28 of 29 pellet samples. The source of one sample from a white-tailed deer was visually identified. The final dataset included 24 white-tailed deer (systematic sample = 4, opportunistic sample = 20), 5 mule deer (systematic = 3, opportunistic = 2), 36 moose (systematic = 10, opportunistic = 26), 15 elk (systematic = 2, opportunistic = 13), and 8 caribou samples (systematic = 0, opportunistic = 8). There were approximately 6.9 million reads from the 88 samples. From the metabarcoding analysis, there were 3.7 million reads for plant DNA and 3.1 million reads for fungal DNA. In total, 921 123 reads were unidentified or unknown at the family level. On average, each submitted sample returned 43 587 (range: 204–195 469) reads of plant DNA and 35 737 (range: 0–195 206) reads of fungal DNA. Samples from white-tailed deer comprised 33% of the total reads, while 8% were from mule deer, 38% from moose, 14% from elk, and 6% from caribou. These values were roughly in-line with the proportion of samples submitted for each ungulate.

Diet composition

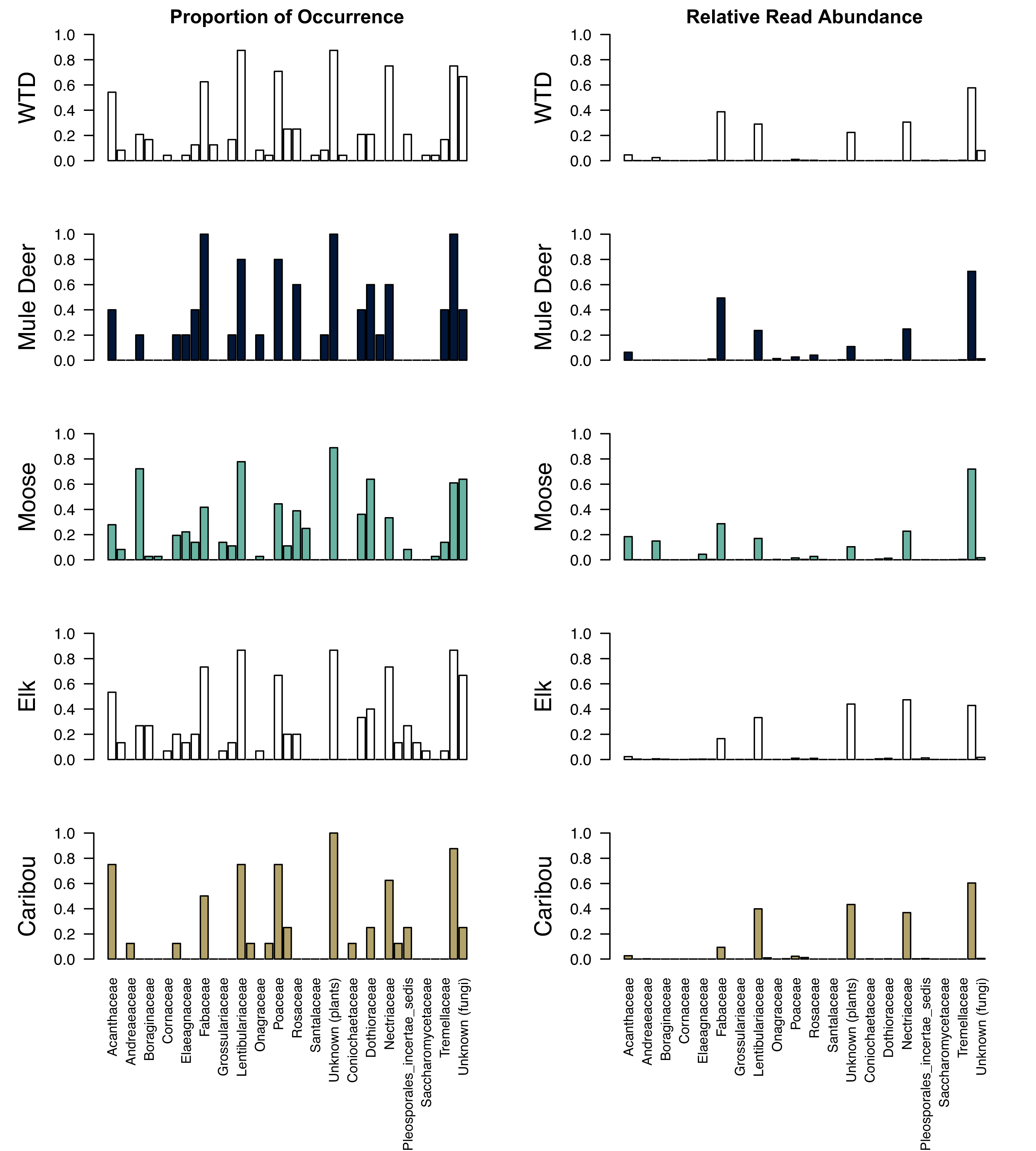

Thirty-seven distinct taxonomic families were identified by the metabarcoding process (

Fig. 2; Supplemental Table 2). Bionectriaceae, Herpotrichiellaceae, Nectriaceae, Pleosporaceae, Pleosporaceae

incertae sedis, and Tremellaceae were families of fungi classified as “probably lichenicolous” and associated with a lichen species found in our study area (

Brodo et al. 2001;

Lawrey and Diederich 2018;

Government of Alberta 2022). For all five ungulate species, Lentibulariaceae (carnivorous plants, common butterworts) was one of the most frequent plant families identified within the winter pellet samples (>75% of all samples). Poaceae (grass) was identified in >70% of samples for white-tailed deer, mule deer, and caribou. Grimmiaceae and Santalaceae (mosses and sandlewoods) were only found in samples identified as white-tailed deer, Andreaeaceae and Melanthiaceae (mosses and bunchflower) were found only in caribou samples, and Salicaceae (willow) was found only in moose samples.

The most frequently identified fungal family was associated with decaying organic matter (Trichocomaceae). Nectriaceae, a lichen-associated fungi, was identified in >70% of samples for white-tailed deer and elk. Bionectriaceae, another lichen associated fungi, was only found in white-tailed deer samples, and Herpotrichiellaceae, also lichen associated fungi, was only found in mule deer samples. Psathyrellaceae, a common mushroom fungus in our study area, was only found in elk pellet samples.

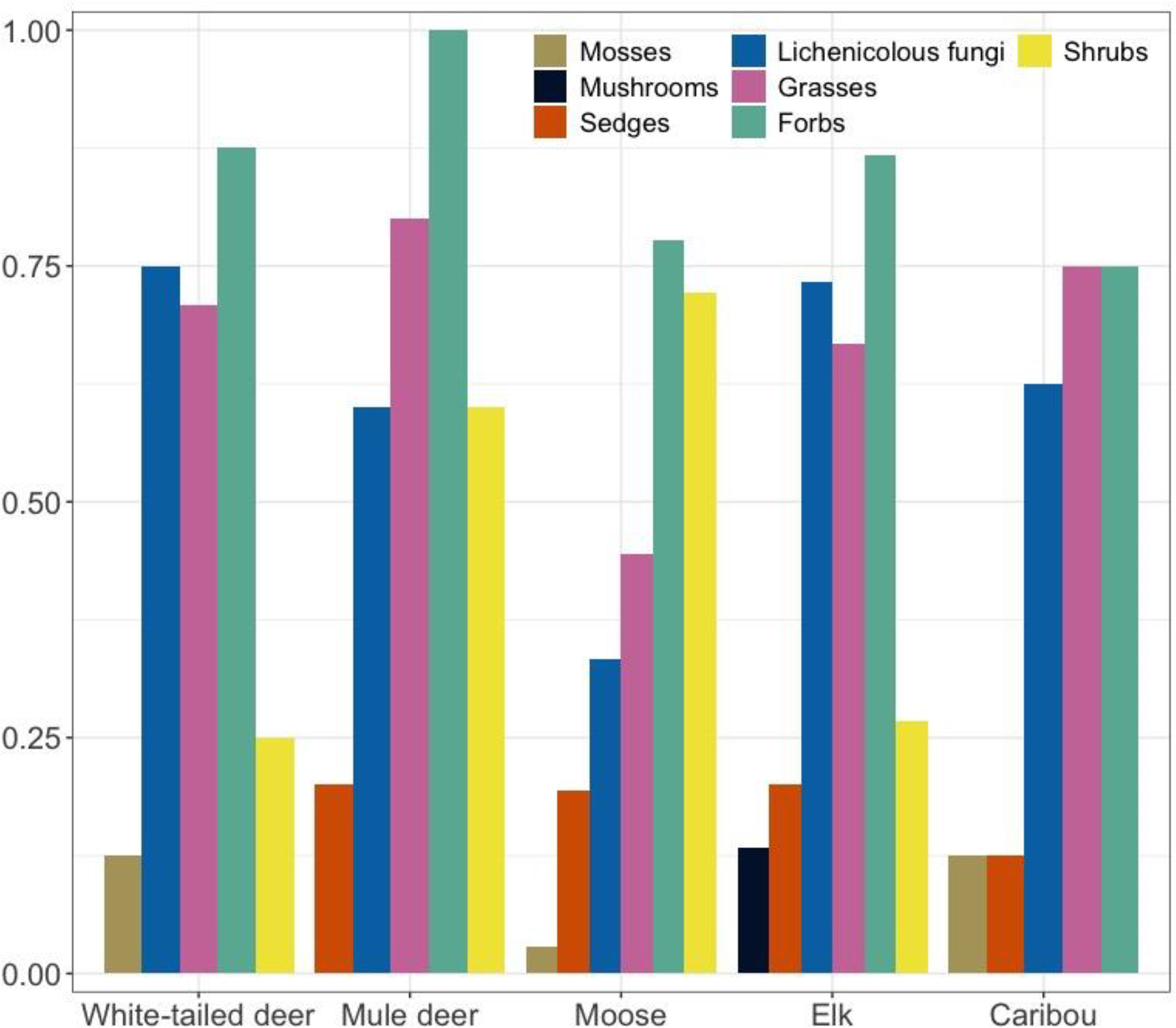

Lichenicolous fungi, grasses and forbs were identified in pellet samples from all five ungulates (

Fig. 3). Shrubs/deciduous trees were identified in samples from all ungulates except caribou, and sedges were identified in samples from all ungulates except white-tailed deer. Mosses were found in pellet samples from white-tailed deer, moose, and caribou.

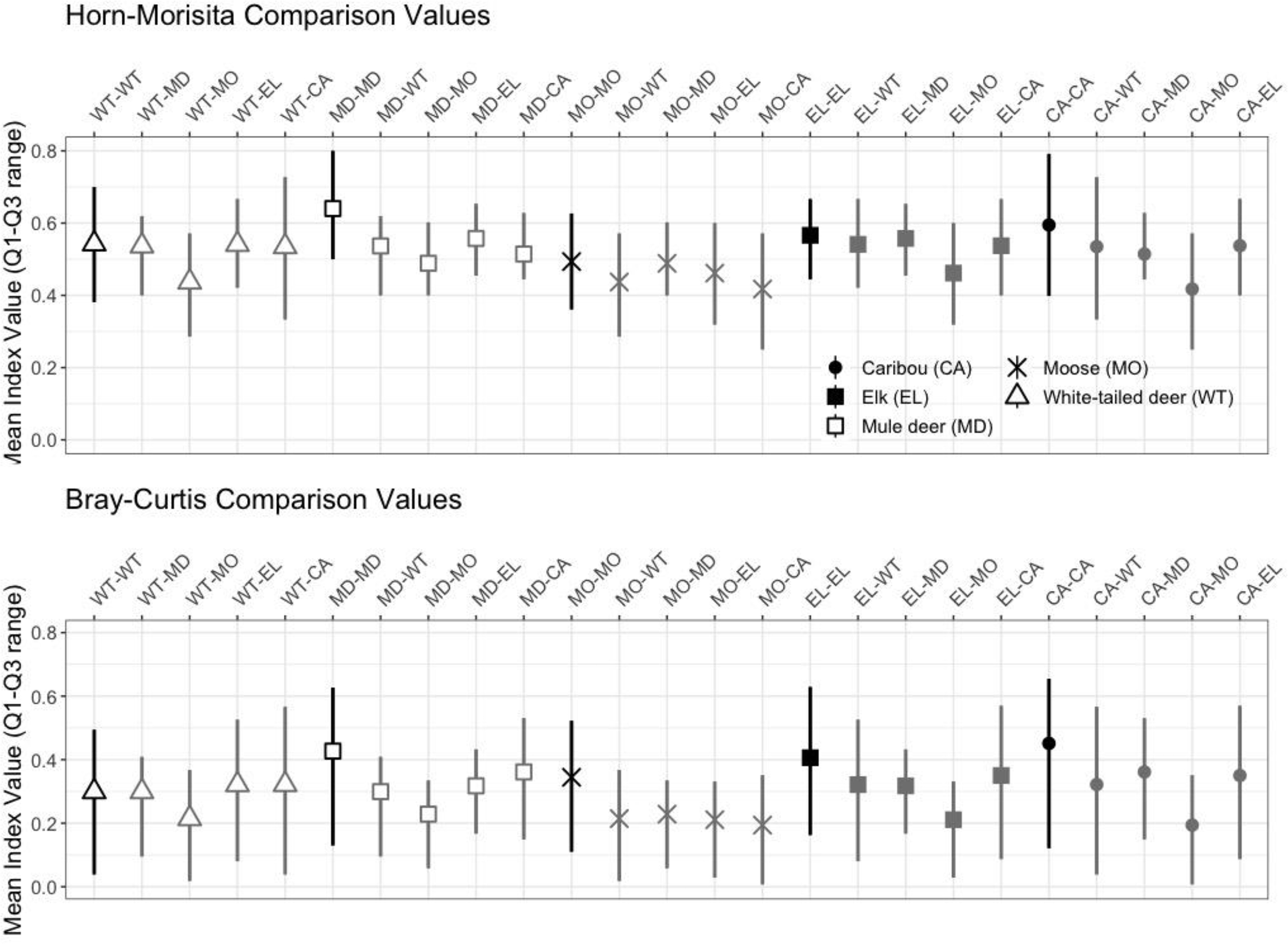

Across samples, the mean Horn-Morisita similarity index ranged from 0.4175 to 0.6402. Samples from the same ungulate were more similar to each other when compared to samples from other ungulates (

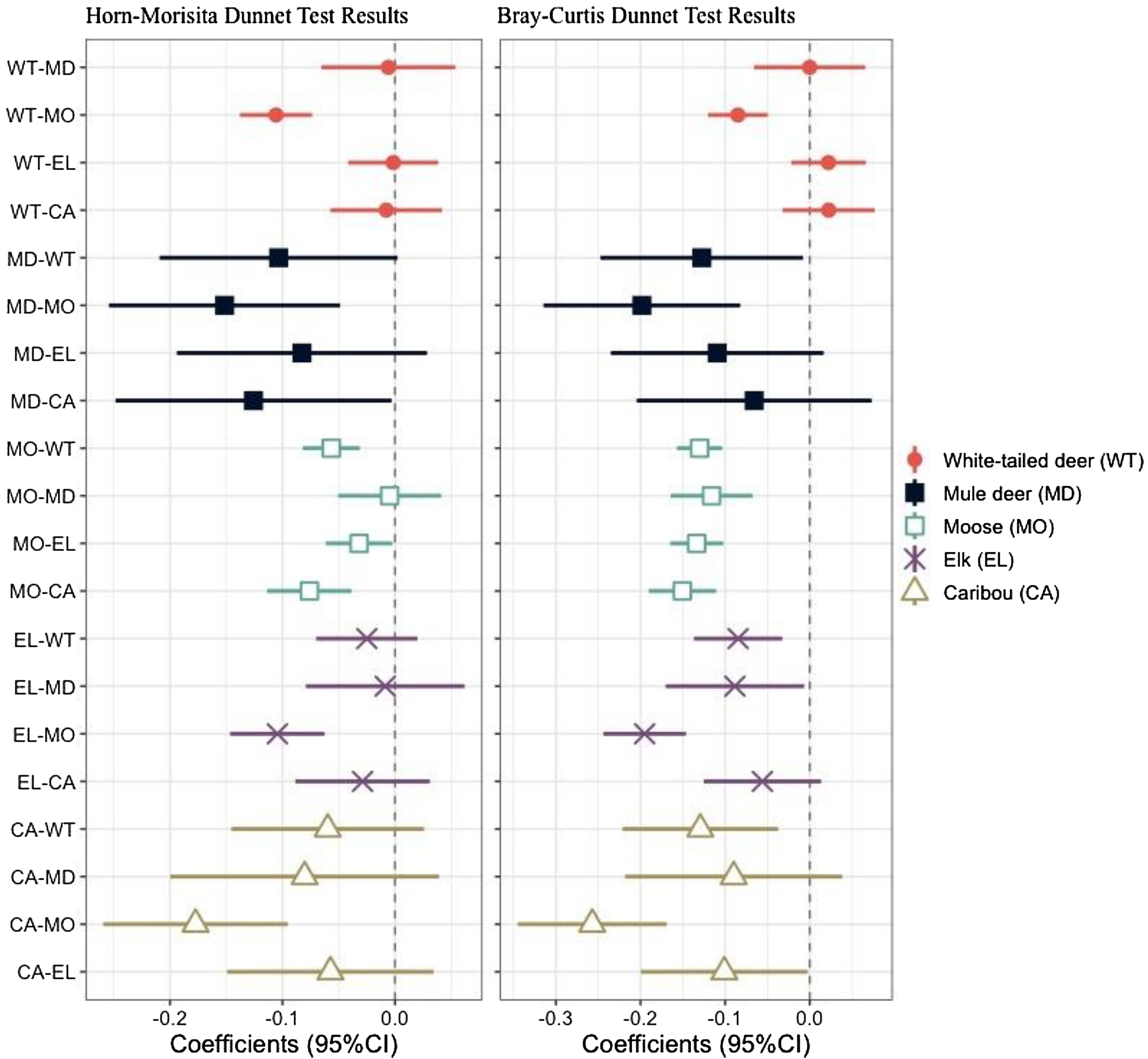

Fig. 5). In general, moose samples had the lowest mean similarity with other ungulate samples and elk had the greatest mean similarity. These differences were typically not statistically significant, except when comparing moose with other ungulates (

Fig. 6).

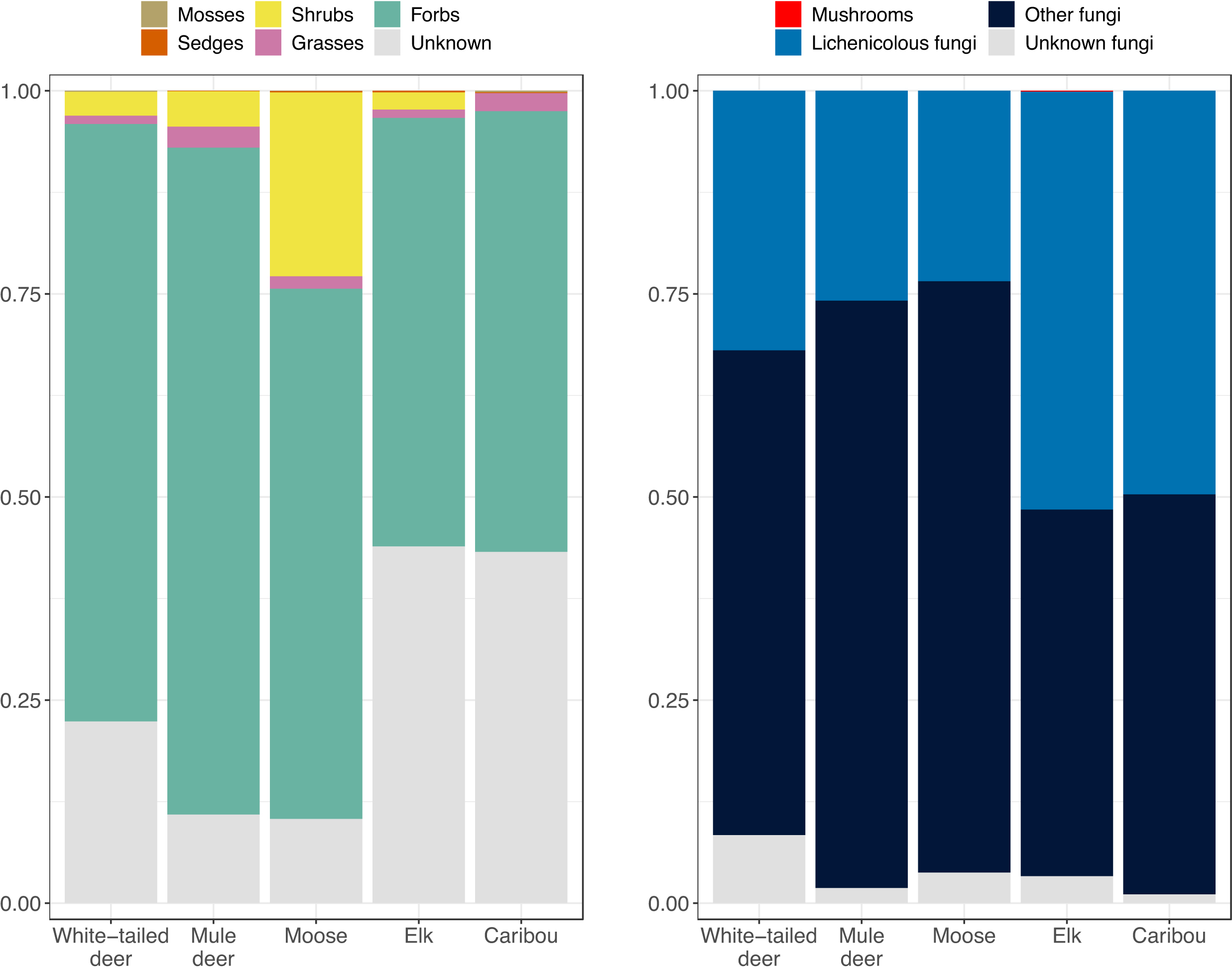

Diet abundance

The top five most abundant families of plants and fungi were similar for all five ungulates: Fabaceae (legumes), Lentibulariaceae (carnivorous plants, commonly butterworts), Nectriaceae (lichenicolous fungi), and Trichocomaceae (fungi associated with decaying material;

Fig. 3; Supplemental Table 2). Acanthaceae (mint) was one of the most abundant families for moose. Considering diet items by forage group, forbs were the most abundant group for all five ungulates, comprising 53%–82% of the reads from plant DNA (

Fig. 4). Shrubs/deciduous trees made up relatively little of the plant reads for deer and elk samples (2%–4%) and were substantially more abundant for moose (23% of plant reads). Lichenicolous fungi made up 23%–49% of the fungal DNA reads for each ungulate. Mosses, mushrooms, sedges, and grasses made up very little of each ungulate's diet.

Bray-Curtis similarity indices revealed that there was separation in diet among the five ungulate species (i.e., index <1.0) and that pellet samples from the same ungulate were more similar in diet to each other when compared to samples from other ungulates (

Fig. 5). The exception to this pattern was white-tailed deer, where individual samples were more similar in diet to elk and caribou than to other white-tailed deer. However, the 95% confidence intervals overlapped for the species-species comparisons suggesting considerable imprecision in the raw data or results of the metabarcoding analysis. The average similarity index for each comparison ranged from 0.1951 to 0.4512 (

Fig. 5). As with the Horn-Morisita index, moose had the lowest mean similarity index, but conversely to the Horn-Morisita results, caribou had the greatest mean similarity index when comparing abundance of each plant or fungal family. Using an ANOVA and post-hoc Dunnett Test, we found these differences to be statistically significant for moose compared to all other ungulates, for mule deer compared to white-tailed deer and moose, for elk compared to white-tailed deer, mule deer, and moose, and for caribou compared to elk, moose, and white-tailed deer (

Fig. 6).

Discussion

This study provides the first diet comparison of the five forest-dwelling ungulates in west-central Alberta. We found that forbs were common in the diet of all five ungulates in this region during winter. The diet of the study ungulates had an overlap of 21%–30% when considering the abundance of plant and fungal families. However, this overlap was less than reported in several previously published studies (41%–95%:

Hobbs et al. 1983;

Leslie et al. 1984;

Singer and Norland 1994;

Kirchhoff and Larsen 1998;

Torstenson et al. 2006), but similar to research from northwestern British Columbia and the Yukon (

Hodder et al. 2013;

Jung et al. 2015). For example,

Hodder et al. (2013) reported that the diet of moose and elk overlapped by 11%, moose and mule deer by 24%, and elk and mule deer by 31%. In our study, moose had the most distinct diet (Horn-Morisita overlap 42%–49%, Bray-Curtis overlap 19%–22%), likely due to the abundance of

Betula spp. that was relatively rare in the diets of the other four ungulate species.

Our results corroborate recent findings that caribou have a more varied diet than previously thought (

Denryter et al. 2017;

Mitchell et al. 2022;

Webber et al. 2022). In particular, the diet of sampled caribou was not dominated by lichen during winter, in comparison to previous research in our study area (

Thomas et al. 1996). We found that 75% of caribou samples contained grass and forb DNA, while 60% of the samples contained DNA associated with lichenicolous fungi. Unfortunately, the resolution of the analysis did not allow for an identification of specific genera that are known forage items of caribou (e.g.,

Cladina spp.,

Cladonia spp.,

Stereocaulon spp.;

Thomas et al. 1996;

Environment Canada 2014), so we could only identify the family of fungi that may be associated with those more specific forage species. In contrast to previous studies (summarized in

Webber et al. 2022), the metabarcoding did not identify DNA of shrubs or deciduous trees in the caribou pellets that we collected. Also, we had a relatively small sample of pellets (

N = 8), greatly limiting the generalizability of the findings to the population as well as woodland caribou, more generally.

Relative to the other four ungulates, moose had the greatest abundance of shrubs and deciduous trees, primarily from the

Betula family, in their diet. In many regions, moose rely on conifer species such as fir during winter (

Hodder et al. 2013). However, we found no conifer in any of the samples that we collected. It is possible that conifers were not a significant component of ungulate diets as the typical forage species (

Abies spp

.,

Taxus spp

.,

Pseudotsuga mensiezii) were relatively uncommon or absent from our study area. Elk are often associated with grass (

Holsworth 1960;

Woods 1972;

Salter and Hudson 1980;

Churchill 1982;

Kohl et al. 2012); however, we found deer, elk, and caribou had similar occurrence of grass species in their diet, and grass was only a small portion of the DNA reads for the individuals we sampled. We found that the diet of white-tailed deer and mule deer was varied, which was expected for these species, but the sample size was extremely small for mule deer (

Franzmann and Schwartz 1997;

Hewitt 2011).

Limitations

The results of this study were informative but must be considered in the context of the limitations of sampling and DNA metabarcoding of fecal samples. Although we have no measure of absolute diet for the species or study area that we sampled, there is the possibility of misclassification of taxonomic family. Indeed, a number of the results were surprising. For example, there was no evidence of conifer trees (Pinaceae) in any of the pellet samples. Previous diet analyses from western Canada reported that moose and deer consumed

Abies spp.,

Pinus spp., and Douglas-fir during winter (

Hodder et al. 2013;

Rea 2014;

Rea et al. 2017;

Koetke et al. 2023). Also, the laboratory analysis revealed some plants that were likely very rare across the study area during winter. For example, Lentibulariaceae, including butterworts and bladderworts, are small flowering plants typically found in wet aquatic habitat. We must assume that the shoots of those plants would be unavailable as forage during winter.

Sampling of fecal pellets occurred soon after snowfall. This resulted in uneven sample sizes and non-random distribution of the sample locations. Collection sites may be biased towards proximity to roads, which can influence the availability of plant species and ultimately diet (

Roever et al. 2008). The small number of samples (

N = 88 for five species) resulted in limited generalizability of the findings. Also, the sample was unbalanced, with relatively few samples for caribou (

N = 8) and mule deer (

N = 5). Finally, animal diets vary spatially and over time (e.g.,

Bojarska and Selva 2012;

DeBano et al. 2016;

Koetke et al. 2023). Future work in our study area would benefit from greater and seasonal sampling that more fully represents spatial variation as well as within and among season differences in diets.

Pellet samples for caribou were provided from previous projects and had been frozen for five years prior to analysis. Long-term storage could have influenced the viability of the DNA with a differential effect of degradation among plant and fungal types (

Nsubuga et al. 2004). However, previous research has shown limited differences in DNA extracted from samples frozen for multiple years (

Gavriliuc et al. 2021). Our results were based on fungal DNA present in the samples, which was then inferred to be lichenicolous based on fungal associations (

Mitchell et al. 2022). We assumed fungal DNA was consumed purposefully by the ungulate. However, it is possible that fungi were not targeted forage items but were consumed incidentally (e.g., endophytic) or fungal spores settled out on pellets after defecation. While DNA metabarcoding is expected to provide higher taxonomic resolution than methods such as microhistology (

Port et al. 2016), we found only 30% of the fungal reads and 60% of the plant reads identified to the genus level.

Key messages

Forage and forage subsidies have garnered attention for their role in apparent competition between caribou and white-tailed deer (

Fisher and Burton 2021;

Fuller et al. 2023). That interaction is thought to be facilitated by less severe winters and an increase in the availability of early-seral plants resulting from human-caused land clearing (e.g., forestry, oil and gas extraction). Despite those concerns, there has been no research into the diet of white-tailed deer in this region. Our study provides some insight into the diet of white-tailed deer in west-central Alberta, and the first comparative analysis of the diet of caribou and four possible apparent competitors. We found that vascular plants, specifically forbs, were a substantial component of each ungulate’s diet. This commonality in diet may influence the overlap between caribou and the other ungulate species in this system.

Competitive exclusion occurs when two species occupy the same niche, resulting in one species being excluded (

Armstrong and McGehee 1980). Our results suggest that there is a relatively low risk of these five ungulates occupying the same forage niche, but there may be competition for specific food items. Caribou rely predominately on lichen for winter forage (

Thomas et al. 1996), and we found lichenicolous fungi in >30% of the samples for each ungulate. Specifically, Nectriaceae made up >25% of the fungal DNA reads. This corroborates other evidence that many ungulates use lichen for winter forage (

Thomas 1990;

Latham and Boutin 2008;

Hodder et al. 2013). Our results provide some evidence of possible exploitative competition between caribou and other ungulates in west-central Alberta. However, we have no understanding of the total consumption of shared plants or lichens among the five ungulates that we studied. Similar family groups within pellet samples does not mean that forage is limiting or that niche overlap has a direct fitness effect for caribou, deer, elk, or moose. In theory, these ungulates could have an identical proportion of each family group within their pellets, but diet could be differentiated at the species level.

We reported some ecologically plausible patterns in the diet of the five species in this study, but indeterminate results suggested that there was still some need to evaluate the efficacy and accuracy of DNA metabarcoding as a method for quantifying diet represented in fecal pellets. For our small sample, we achieved poor taxonomic resolution, relative to other studies and methods. Also, we suspected some misclassification of plant and fungal families. Nonetheless, this method is relatively efficient and could provide a foundation to explore how the concurrent effects of climate and landscape change, among other factors, may influence the nutritional ecology of sympatric Cervidae.