Did the COVID-19 pandemic disrupt food security in West African rural communities? Survey results from four regions of Senegal and Burkina Faso

Abstract

Introduction

Method

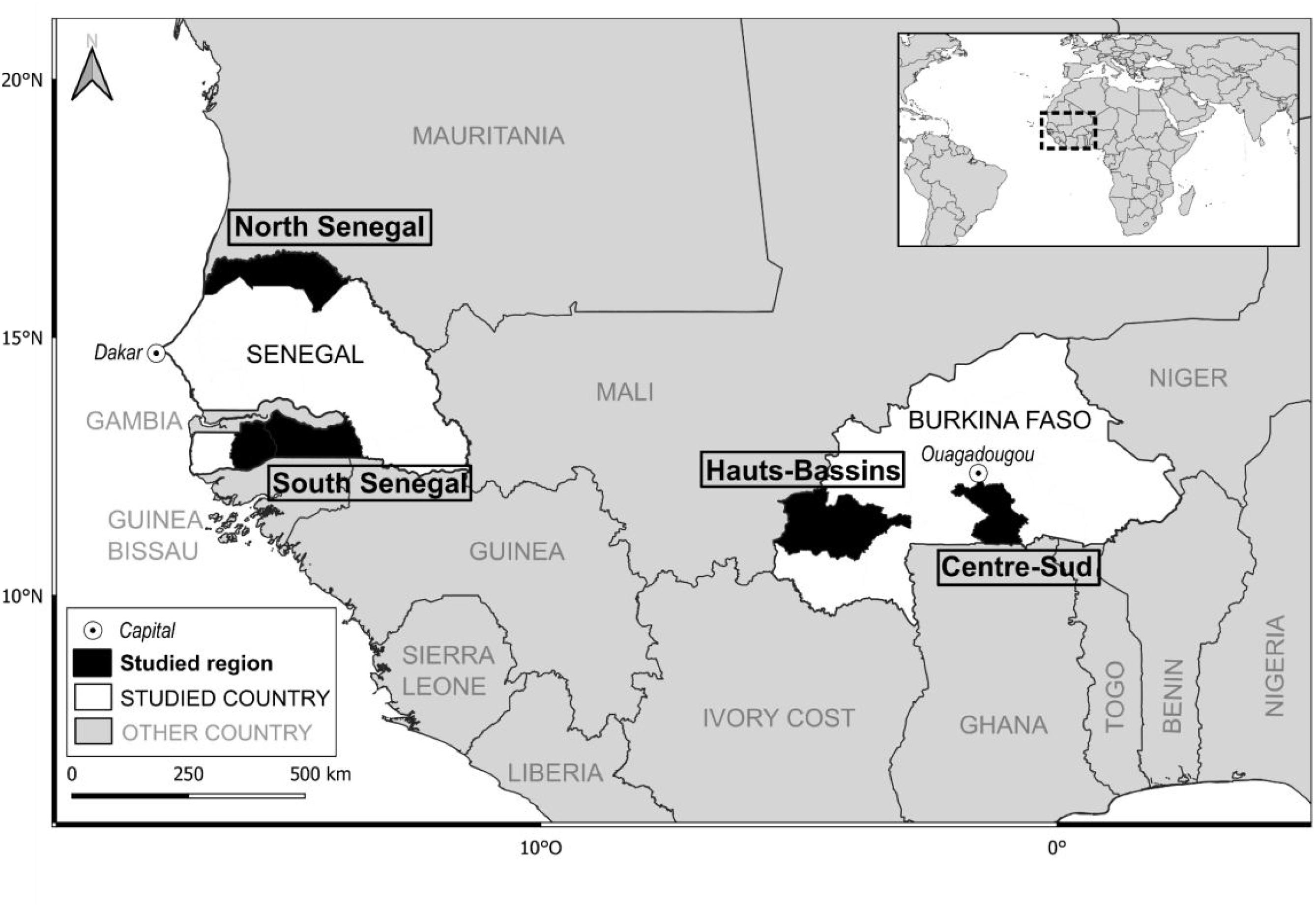

Study areas

Surveys

Thematic content analysis

Results

Interviewees’ characteristics

| Country | Community | Gender | Profession | TOTAL | TOTAL/community | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmer | Trader | Leader | |||||

| Senegal | North | Men | 16 | 10 | 3 | 29 | 60 |

| Women | 10 | 16 | 5 | 31 | |||

| South | Men | 17 | 9 | 6 | 32 | 61 | |

| Women | 11 | 14 | 4 | 29 | |||

| Burkina Faso | Hauts-Bassins | Men | 7 | 10 | 6 | 23 | 52 |

| Women | 10 | 14 | 5 | 29 | |||

| Centre-Sud | Men | 9 | 11 | 7 | 27 | 57 | |

| Women | 9 | 16 | 5 | 30 | |||

| TOTAL | 89 | 100 | 41 | 230 | |||

Interviewees are aware of the pandemic and the restriction measures

Food insecurity and disparities among sexes increased due to sanitary measures

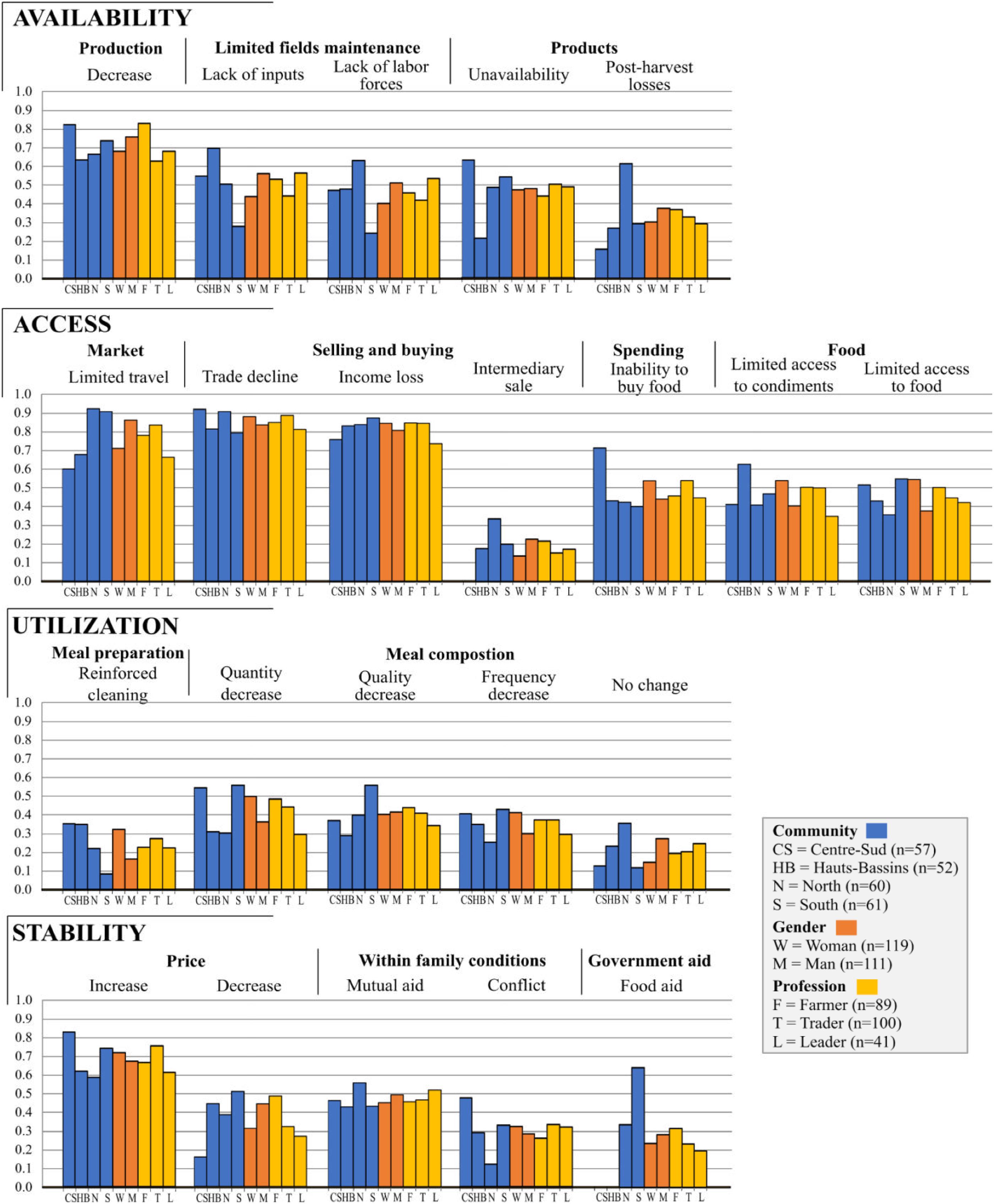

Food availability

| Pillars | Themes | Percentage (%) of responses for each subtheme | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Availability | Production | 71.7 decrease | 20.4 livestock reduction | 3.5 change | ||||

| Limited field maintenance | 49.6 lack of inputs | 45.7 lack of labor forces | 16.1 lack of seeds | 11.3 lack of tools | ||||

| Environmental conditions | 13.9 bad weather | 7.4 pests/animals | 1.7 diseases | |||||

| Products | 47.4 unavailability | 33.9 post-harvest losses | ||||||

| Access | Market | 77.8 limited travel | 73.9 attendance decline | 69.1 closure | 6.1 police conflict | 3.0 focus on local market | ||

| Selling and buying | 85.2 trade decline | 82.2 income loss | 17.8 intermediary sale | 5.7 door-to-door sale | ||||

| Cross-border exchanges | 54.3 border closure | 53.9 exchanges decrease | 14.3 illegal crossing | 14.3 negotiation with the police | ||||

| Spending | 48.3 inability to buy food | 12.2 decrease in financial reserves | 7.8 indebtedness | 5.7 increase in health | 5.7 inability to pay school | 2.6 inability to pay health fees | ||

| Food | 46.5 limited access to condiments | 45.7 limited access to food | 4.3 limited access to water | |||||

| Utilization | Transformation | 7.4 restricted access | 5.7 limited mutual aid | |||||

| Meal preparation | 24.3 reinforced cleaning | 4.8 distanced meals | 3.9 absence of shared meals | |||||

| Meal composition | 43.0 quantity decrease | 40.9 quality decrease | 35.7 frequency decrease | 20.4 no change | ||||

| Stability | Price | 69.1 increase | 37.4 decrease | |||||

| Within family conditions | 46.5 mutual aid | 30.0 conflict | 13.9 respect of sanitary measures | 9.6 lack of food | 9.6 lack of money | 3.5 lack of privacy | 1.3 respect of decisions | |

| Family mutual aid | 13.0 household chores | 9.6 farm chores | 8.3 finance | 6.1 food search | 3.9 lack of | 1.3 trade chores | ||

| Community support | 12.2 women groups | 10.0 sensibilization | 7.8 mutual aid | |||||

| Government aid | 31.7 lack of | 25.7 food aid | 4.8 money aid | 1.3 agricultural aid | 0.4 medications | |||

Note: Subthemes were coded from the interviews, then reassembled in themes and dimensions. Each subtheme is followed by the percentage of respondents who mentioned this subtheme.

What we prefer to have as support is that the State can provide us with mills, tractors to cultivate in our fields. For our market gardening too, if we could irrigate our gardens, that would greatly simplify the work. (Woman farmer – South Senegal) [translation from French, E.Q.]

We who are in onion production had a problem with the flow of our products because we no longer had the possibility of selling in other areas with the closure of the weekly markets and the state of emergency. We also had a big problem with transportation. (Man farmer – North Senegal) [translation from French, E.Q.]

| Pillars | Availability | Access | Utilization | Stability | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Themes | Decrease in production | Lack of labor forces | Limited access to inputs | Unavailability | Market closure | Decrease in attendance | Difficulty in traveling | Decrease in trade | Loss of income | Inability to buy food | Decrease in quantity | Decrease in frequency | Decrease in quality | Price increase | Price decrease | |

| Availability | Decrease in production | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| Lack of labor forces | 0.48 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| Limited access to inputs | 0.48 | 0.41 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| Unavailability | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Access | Market closure | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Decrease in attendance | 0.63 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.61 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Difficulty in traveling | 0.60 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Decrease in trade | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Loss of income | 0.67 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.61 | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Inability to buy food | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Utilization | Decrease in quantity | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 1.00 | ||||

| Decrease in frequency | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 1.00 | ||||

| Decrease in quality | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 1.00 | |||

| Stability | Price increase | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 1.00 | |

| Price decrease | 0.36 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 1.00 | |

Note: K corresponds to the percentage of respondents who mentioned two subthemes. For example, K between Decrease in production and Loss of products is equal to 0.45, which means that 45% of respondents who mentioned Decrease in production or Loss of products, mentioned both subthemes. The closer K is to 1, the stronger the relationship between subthemes is.

Before the pandemic, for one hectare I harvest 20 bags of 50 kilograms of peanuts, during the pandemic I had eight bags because there was no manpower who could help me in the fields. For millet and maize, I had ten bags before pandemic and five bags during pandemic. (Man producer – South Senegal) [translation from French, E.Q.]

Yes, we had difficulty getting fertilizer because those who easily received fertilizer before were the cotton growers but since the disease started this has changed everything, which has led a lot of growers to stop cotton production because men were going to Mali to buy fertilizer at high prices now. (Woman producer – Hauts-Bassins, Burkina Faso) [translation from French, E.Q.]

Access

As I said earlier, it was easier to sell production before the pandemic. If the production exceeded the local market, it was taken to other localities. It all ended with the onset of the pandemic. We closed the cattle market, the weekly markets. The shops and restaurants where our chickens were sold have been closed. This situation makes things difficult. (Woman producer – North Senegal) [translation from French, E.Q.]

If, for example, the woman is arrested, it is serious because she has to come home to take care of the children. Whereas when we arrest the man, even if we hold him there all day. it has no consequences. But if it's the woman, she can’t stay outside for long, she has to give them money to be able to pass. (Woman trader – Centre-Sud, Burkina Faso) [translation from French, E.Q.]

You know that if you bring your products and are able to sell everything you don’t have a problem with the transport [laughter] yeah but when you cannot sell all [pause] it's a problem! If you sell all your products, the price of transport is no longer a problem for you. (Man trader – Centre-Sud, Burkina Faso) [translation from French, E.Q.]

We don’t win. There is no money, there is poverty. If you don’t have the money, what are you going to buy with? Nothing. (Woman trader – Hauts-Bassins, Burkina Faso) [translation from French, E.Q.]

No, some ingredients like oil are no longer accessible because you don’t have the money to buy them. You can’t go to the markets to buy the ingredients, you just cook what you have at home. As a result, the quality of the meals has changed. (Woman farmer – South Senegal) [translation from French, E.Q.]

We didn't even see people coming to buy it. You have to put your production on a truck and deliver it to someone in Dakar. You don’t even get in that truck. And when the latter has finished selling, he sends you your money (Man Trader – North Senegal) [translation from French, E.Q.]

That is to say that the Covid has made us aware of the issue of food sovereignty. How to consume what we produce because it is a shock. This shock showed us that there is a need to work to satisfy local consumption from local production. This really, the peasant organizations are working on it and even individuals and families are aware of this. We hope that in relation to this situation, people will take more head on everything that is the question of local consumption so that this issue can be settled definitively. In any case, this is a great opportunity for people to be sensitive to this issue as well for food. Well, maybe we can’t regulate everything straight away, but we can regulate the important part of consumption. It awakened awareness of this need. (Man leader – North Senegal) [translation from French, E.Q.]

Utilization

When the disease has come, when we wake up, we wash the dishes well, we clean the whole house, let everything be clean and then we cook the food. When it comes to eating, everyone washes their hands with soap, and then we eat. (Woman leader – Centre Sud, Burkina Faso) [translation from French, E.Q.]

It’s complicated to go to the machine [mill] since everyone is talking about the disease there. We all stay outside and take turns entering according to the order of arrival. (Woman Trader - Centre-Sud, Burkina Faso) [translation from French, E.Q.]

That before then, we had enough to eat and there was always more to keep. But now we can manage because there are no more. That if you take everything to prepare, with a full pot to consume morning, noon and evening, that will not be enough. Now, if we eat twice a day, it’s good. Before then, we could eat 3 times a day, in the morning, at noon and in the evening. But now we've canceled breakfast. (Woman trader – Centre-Sud, Burkina Faso) [translation from French, E.Q.]

Stability

Transport has become difficult since there are not many vehicles left to go to Ouaga. Before we paid 2000 CFA, today it has become 3000 f CFA, 3500 f CFA [1000 f CFA represent approx. $2.00 CAD]. (Woman trader – Centre-Sud, Burkina Faso) [translation from French, E.Q.]

Last year, red sorghum was sold at 250 f CFA per dish [about 3 kg], this year it is 600 francs, it is because there is no food that it goes up. (Woman farmer – Centre-Sud, Burkina Faso) [translation from French, E.Q.] – (note: red sorghum is/is not produced in this community)

The coronavirus turned everything upside down with the measures and restrictions, product sales had become very difficult, for example a product that cost 500f CFA could be sold for 100f CFA. Vendors were crying because they couldn’t see buyers and the markets were closed. (Woman Farmer – North Senegal) [translation from French, E.Q.]

Yes, this change is positive because even s the husband did not stay at home very often, now he stays at home and you can talk to each other. It’s good for the heart and even for the children, it's good to discuss with them because it allows you to have affinities with your loved ones and that’s a good thing. (Woman trader – North Senegal) [translation from French, E.Q.]

There is the problem of money the food you could have if you come and say you didn’have it, there are women who don’t believe when you say there isn't. There is dispute at this level. (Man trader – Hauts-Bassins, Burkina Faso) [translation from French, E.Q.]

Disparities among communities affect food security

The local market contained vegetables because they could no longer sell their harvest. Market gardeners brought their goods to the local market. (Woman farmer – North Senegal) [translation from French, E.Q.]

Discussion

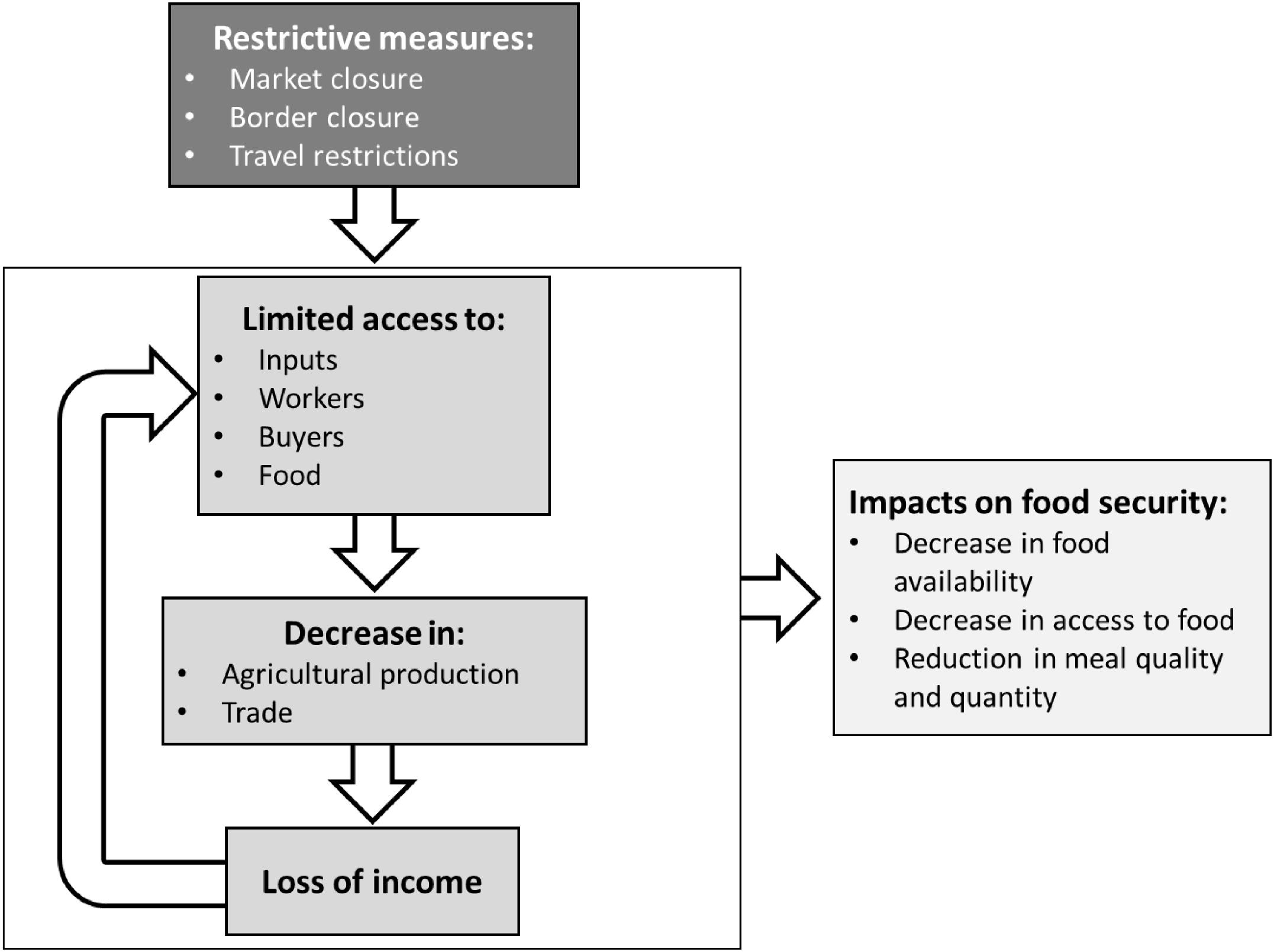

Vicious circle

Toward a food system transformation in the face of crisis

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

References

Supplementary material

- Download

- 20.37 KB

- Download

- 52.55 KB

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Copyright

Key Words

Sections

Subjects

Authors

Author Contributions

Competing Interests

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Other Metrics

Citations

Cite As

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

There are no citations for this item