Co-creating Ethical Space in wildlife conservation: a case study of moose (Mooz; Alces alces) research and monitoring in the Robinson Huron Treaty region (Ontario, Canada)

Abstract

Graphical Abstract

Positionality

Introduction

Methods

Approach

Study area and participants

Semi-structured Interviews

Transcription and coding

Results

Participants’ relationships to moose

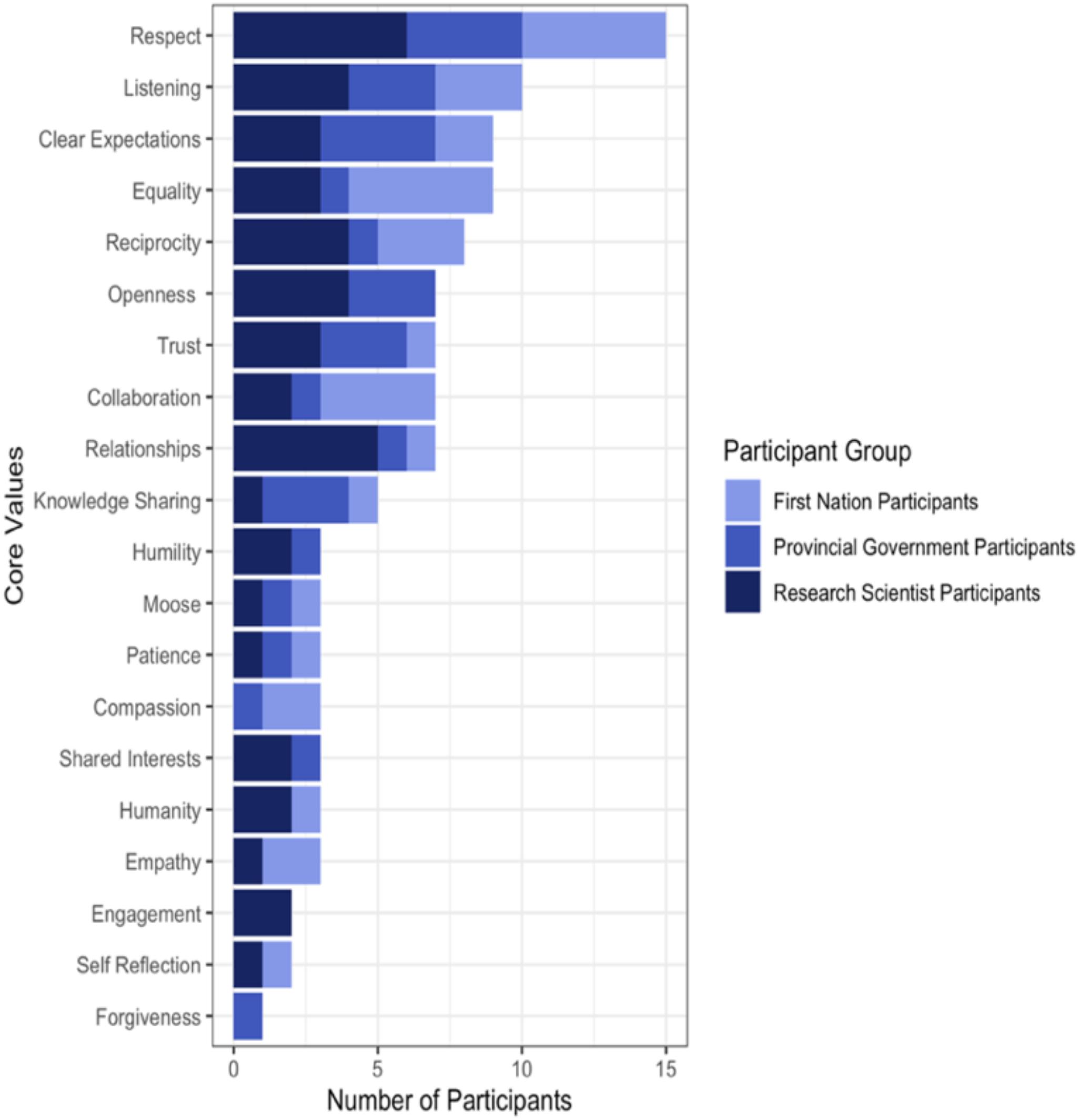

Defining and fostering core values

Respect

“I guess it's context specific. When thinking about getting folks together who may have different cultural backgrounds, or knowledge systems, or ways of knowing, or being, I think respect can mean many things, and I think it can differ with individuals or communities or Nations… but when I think of respect, I think of respecting all ways of knowing, being, knowledge systems, not considering one way of knowing or being as superior to another. Respect means… being patient, listening to one another. Respect means… allocating time, you know, a sufficient amount of time. Like, invest time into relationships, spending time on relationship building, that's respect, right? Respect for one another. Respecting cultural protocols. So, for example, if Indigenous Peoples were part of the meeting, or gathering, typical protocols might be to open with an Elder prayer or a few words and to close, maybe to have a smudge. So being respectful, even if things you don't understand, potentially, and listening and learning” – Anonymous Participant

| Value | Example tangible actions |

|---|---|

| Respect | • Allocate time during early stages of collaboration for casual opportunities to build relationships and continue meaningful engagement • Engage early to ensure all perspectives are considered during planning and maintain constant communication throughout • Actively create opportunities for all attendees to share in ways they are most comfortable (e.g., storytelling) • Use of a talking stick to hold space for the speaker (relates to culture-specific protocols, discuss among partners to determine appropriateness) • Physically and mentality present during gatherings and engaging in active listening rather than passive • Situate people in circles when gathering to avoid hierarchical-like settings • Have a tangible item present to represent and show respect for moose (e.g., hide, drum, or antlers) |

| Listening | • Avoid interrupting others • Acknowledge others when they contribute knowledge, comments, or concerns rather than dismissing or ignoring • Listen for the purpose of understanding and learning, rather than responding |

| Clear Expectations | • Identify a general objective • Co-create a set of guidelines to ensure that everyone agrees and understands how the partnership process will take place • Hire a facilitator or moderator to uphold agreed upon guidelines |

| Equality | • Select gathering locations that reflect and celebrate the diverse peoples, cultures, and knowledges present and infuse opportunities that support cultural practices, if desired • Physical spaces—horizontal leadership, attendees at the same physical level (contrasted with a stage or podium) and in circles • Equal opportunities for attendees to share and in various ways (e.g., microphone, small groups, and written) • Recognize the weight of who speaks first and fill this role with careful consideration • Balanced representation (e.g., gender, age, and race) |

| Reciprocity | • Dedicate time at onset to determine how the partnership will benefit everyone involved • Summary reports in a format that benefits all. Isolating concerns, discussions, findings, etc., may help grant proposal writing, determining future steps, advocating for priorities, or influencing policy decisions • Invest in the partnership by spending time on and learn from the land, embracing opportunities to learn/engage with cultural traditions, share conservation techniques, and give back outside of project boundaries and requirements |

| Openness | • Embrace and include cultural practices (e.g., opening prayer, smudging, and tobacco offering) to open minds, foster good intentions, and speak on behalf of past, present, and future generations • Position participants in a circle to foster safety and security • Reflect on the partnership as a dynamic journey that may change directions based on priorities • Careful consideration to the creation and use of agendas and whose priorities they reflect. A co-created “purpose” or “outline” was preferred and recommended to allow for more flexibility • At an individual level, being available, interested, and receptive of learning about other’s perspectives through active listening |

| Trust | • Trust does not develop with one single action, but with an accumulation of actions and time • Consistency in who is present at gatherings and in communication among partners • Transparency of intentions • Follow through on responsibilities and promises |

| Collaboration | • Facilitate partnerships that are built upon an ongoing process and continuous dialogue • Co-create research and monitoring priorities and approaches to addressing them • Proceed at a pace that all participants feel comfortable, with recognition that building trust and relationships take time • Guided by shared values; therefore, specific actions relate to those of all other values |

| Relationships | • Dedicate time and resources to invest in relationship building prior to sharing knowledge or making decisions • Small consistent actions over time—same people, continuous dialogue, and reciprocity • Build relationships at a personal level outside of formal discussions (e.g., by sharing a meal, coffee, or time on the Land) • Gather throughout the partnership for the purpose of building relationships, without seeking project-related benefits |

| Knowledge Sharing | • Intentionally create physical spaces for knowledge sharing that foster equality and openness among participants and knowledge systems (see above). Importance of spaces that are familiar, comforting, and welcoming (e.g., out on the Land) was emphasized when sharing knowledge • Actively create welcoming and meaningful opportunities for all to share (relating to respect, listening, and openness; see above) • Consider appropriate group size, preference for smaller sizes when sharing knowledge • Time of year for gatherings should be discussed among partners to align with the interests of all partners (consideration to cultural practices, capacity, and accessibility) • Produce consistent updates/summaries following discussions that are accessible and available to all participants |

Note: Core values listed only include those identified by more than five participants.

“Were you seated as if you were sitting at a residential school listening to your nun speak? Or were you sitting in a circle where you're comfortable together? The only reason I say something like that is because I think those are the things that, when it comes to relationship building and understanding who you are working with, knowing that traumas and triggers are there, and that generations of our people suffered, and knowing to be mindful of those things, and seating yourself differently, so to not cause trauma and triggers” – Samantha Noganosh

Listening

“Listening, listening, listening, listening, you don't need to have something to say for everyone's comments… you don't need to tear someone's ideas down, every time they speak. They probably think those things for a reason. Find out why they think that way, and why they're saying the things that they are communicating.” – Anonymous Participant

“Listening doesn't mean you can't speak. It just means that while someone else is speaking to you, you“re letting them finish and maybe giving them that couple of seconds and not feeling like you need to come back with a response or … an example or … something comparable. You just listen and validate what they said … It's just the acknowledgement ‘I heard you. I”m absorbing it, and I want to take what you're telling me’ and you move it forward.” – Anonymous Participant

Clear Expectations

“Knowledge co-production is supposed to be goal oriented. And, if they are shared goals, then the opportunity for those diversity of perspectives to come around and disagree in a safe environment becomes possible.” – Anonymous Participant

“I think [the goal] deserves careful attention and consideration, and is not something that should be rushed into… Is it relationship building? Or is it relationship building with the added benefit that we are talking about moose? Or is it purely moose? So, for me something like this [defining the goals] would … change the narrative. It'll change the way people think, I think” – Anonymous Participant

Equality

“I really think it's critical to reflect on the power dynamics or the perceived power dynamics. Who has power in the relationship? And purportedly from where does that power come?… So when we think about, coming together for a conversation around moose, I think it's a really important question for particularly the participants who think they have power or purportedly have power, to reflect on that power and then do the inverse. If you have power, you don't really need to tell people you have that power, you need to go out of your way to make clear that that power isn't going to be weaponized in your conversation, that if we are genuinely working towards a common goal and a shared equitable space” – Anonymous Participant

“I think the physical space is more important than I think we give it credit for. Simple things like putting tables in circles and having more horizontal leadership… it's not someone standing at a podium, speaking down at everyone. It's everyone on the same level, physically. Everyone in the same kind of plane, physically” – Anonymous Participant

“We have to understand that it may not be all the time that we have to demand these things [hosting in community]. But bringing it to a parity where it's evenly weighted. Because it's not reasonable to expect them [non-community members] to always come to the community and do the meetings. But by incorporating some of these values that we're talking about, kind of brings us to that more ethical space than what it is right now, without getting too demanding on them too, though. Because we don't want to start doing what they are doing to us, right? By demanding them always to come here.” – Anonymous Participant

Reciprocity

“And that could take compromise and … arguments and frustration, but just to find a space where everyone can benefit at least a little bit and including, hopefully, moose” – Anonymous Participant

“I think something very specific that can help foster reciprocity is having very clear and written out, asks, expectations, and outcomes. Not that that is the only way that reciprocity can be fostered, but just to ensure that everyone signing on to the scenario understands what they are getting out of it. And I think those things need to be written down and acknowledged by everyone” – Anonymous Participant

Openness

“Openness to other worldviews, other opinions, other knowledge, things not working out, things having to take a turn, because of different priorities or concerns of other people. And, just being open to not knowing all the answers or everything at the start and kind of going on a journey with everyone else there” – Anonymous Participant

“…having a schedule of some sort, but not making the schedule very rigid. Having some fluidity to it… So you just have the general things that are going to be discussed, and… just having those open, round table, circle discussions” – Norm Dokis

Trust

“We get together and we talk about these things. We develop trust, but it often has to be done at a personal level… It takes time and needs to be acknowledged that it takes time. It takes a long time to get some level of trust to the point where you can actually work together.” – Anonymous Participant

“I think one of the worst things that non-Indigenous researchers, academic academics, government biologists can do is to continue to say they“re going to do something and then not do it. In my mind, it's almost better to just not even say you”re going to do something. Because that's what the historic relationship has been between Indigenous Peoples and crown governments and colonial institutions it is just a constant letdown and a constant building of mistrust, like saying you're going to do one thing and then doing another and, and not much transparency” – Anonymous Participant

Collaboration

“Like the Two Row Wampum: walking the same road, right? The same path, but two different people. I think that's important to carry on into meetings as well, understanding that and we“re not here to wrestle over one or the other. And to come out a winner or a loser, it's to work together, because we have that same road where we”re walking down, right” – Anonymous Participant

“It should be an ongoing process and a continuing dialogue, I think, more than a one-off workshop or a session, you know, even so, I think, yeah, that's how I would view it is a regular occurrence, you know, that we're going to keep doing this, you know, at some, like regular intervals over such a time. And I think that would even, if sometimes there wasn't a lot of information to share, it keeps people engaged in the process. And I think it also provides opportunity for people to get to know each other better, and to I think there's value in that.” – Anonymous Participant

“…perhaps these wampums at meetings are very important as well, because they kind of like are a living entity, when you bring them out… and can contribute to what the intent of everything that we“re doing here… between the two parties, the First Nation and a proponent or the government, is that we”re here to work together for a common benefit for both parties.” – Anonymous Participant

Relationships

“I do like to think about shared community and how we build communities, and how we take things away from communities but need to be cognizant of putting the labor in to build the community or, otherwise we don't have it. So, when we have shared interests or shared resources, I think a lot about the concept of community, and what it is, and how it takes work. I guess within that, for me, the idea that relationships are also labor, whatever they might be, whether they're between organizations or between individuals” – Anonymous Participant

“So, I think more time… should have went into relationship building, as opposed to seeking benefits. For example, instead of you know, just having, you know, meetings where you're talking business, business, business, how about hanging out in the community and get to know each other? And yeah, so I think, yeah, definitely. trust building and relationship building, I think should be more prioritized.” – Anonymous Participant

Knowledge sharing

“The more that we can work together and share the knowledge, I think the better off it is, given that often there can be two different viewpoints or two different ways of seeing it… Sharing that knowledge and understanding at the end of the day, creates more knowledge” – Anonymous Participant

“I think Lands-based would be super ideal for any sort of [knowledge sharing] discussion, because the Land is medicine too, right? And, how can folks get stressed out if they walk out the door, and they are, you know, under a canopy of trees, or sitting by a lake. Because the Land is medicine, and that's what you need. I think in these scenarios, where there's been poor relationships in the past, having an environment around you that can be so healing, and I think that would be ideal” – Anonymous Participant

Application

Consider the process to support long-term partnerships

“It's when we think about the methodology of capturing traditional knowledge, you have to build trust, you have to go back over and over again, you can't just go in once and be parasitic about your approach.” – Norm Dokis

Importance of building meaningful relationships

“I think those [values] cover it, in a long, long-term perspective as well, like this is founded on relationship. So, I think you can't do this kind of thing without forging a relationship, and then the relationship has to be very genuine” – Anonymous Participant

Ability to evolve through reflection and striving to do better

Adaptive, sort of. I don't think anyone will get it right, the very first shot…So to have that ability to grow and learn from one another, and to know that's a priority, so that everyone in the room says anything you see that can be improved, like of something you liked or didn't like,” – Anonymous Participant

Concluding remarks

Acknowledgements

References

Supplementary material

- Download

- 61.26 KB

- Download

- 15.24 KB

- Download

- 141.25 KB

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Copyright

Data Availability Statement

Key Words

Sections

Subjects

Authors

Author Contributions

Competing Interests

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Other Metrics

Citations

Cite As

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.