Identifying indigenous knowledge components for Whudzih (Caribou) recovery planning

Abstract

Introduction

Materials and methods

Positionality statement

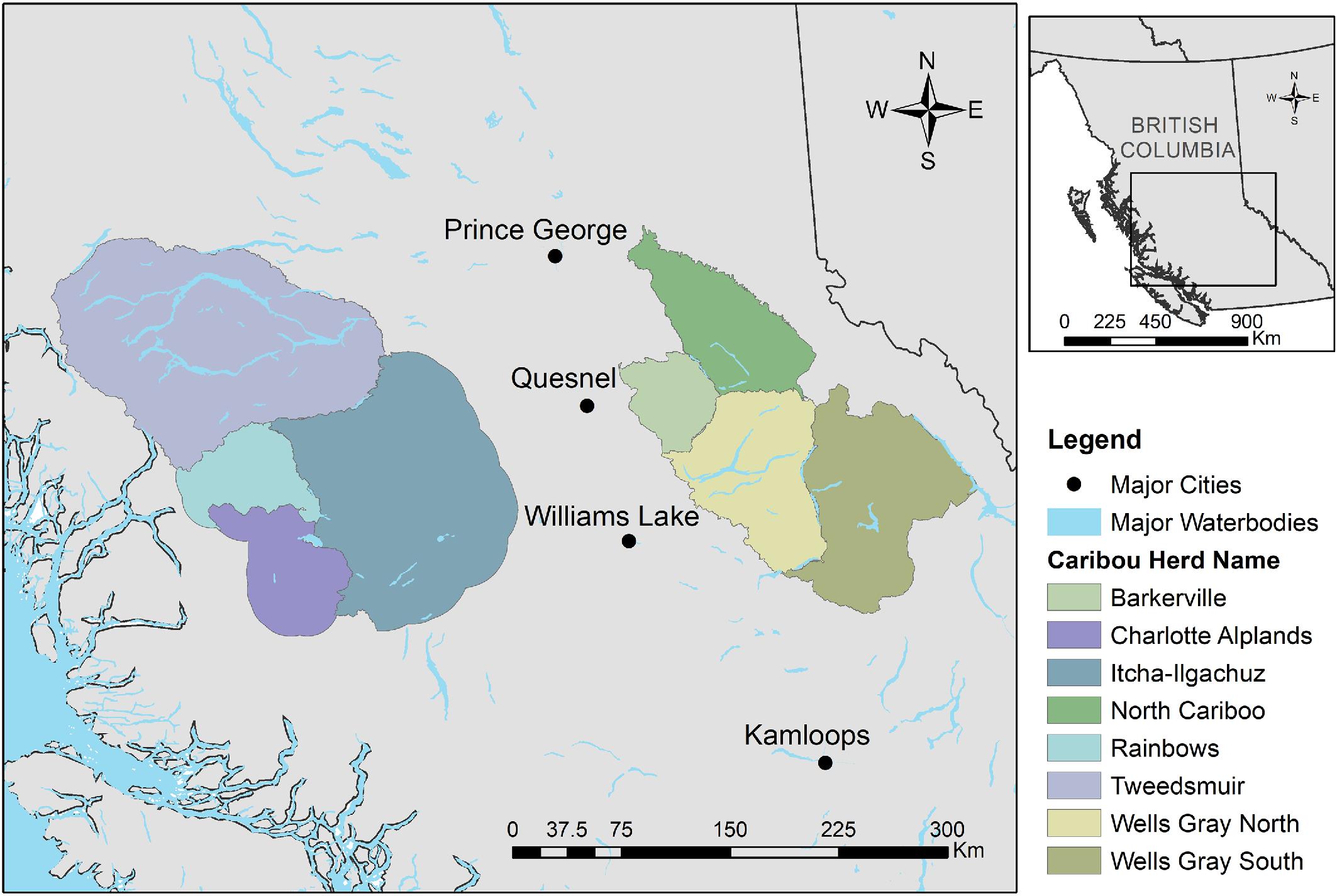

Study area

Survey of professionals

Indigenous knowledge interviews

Results

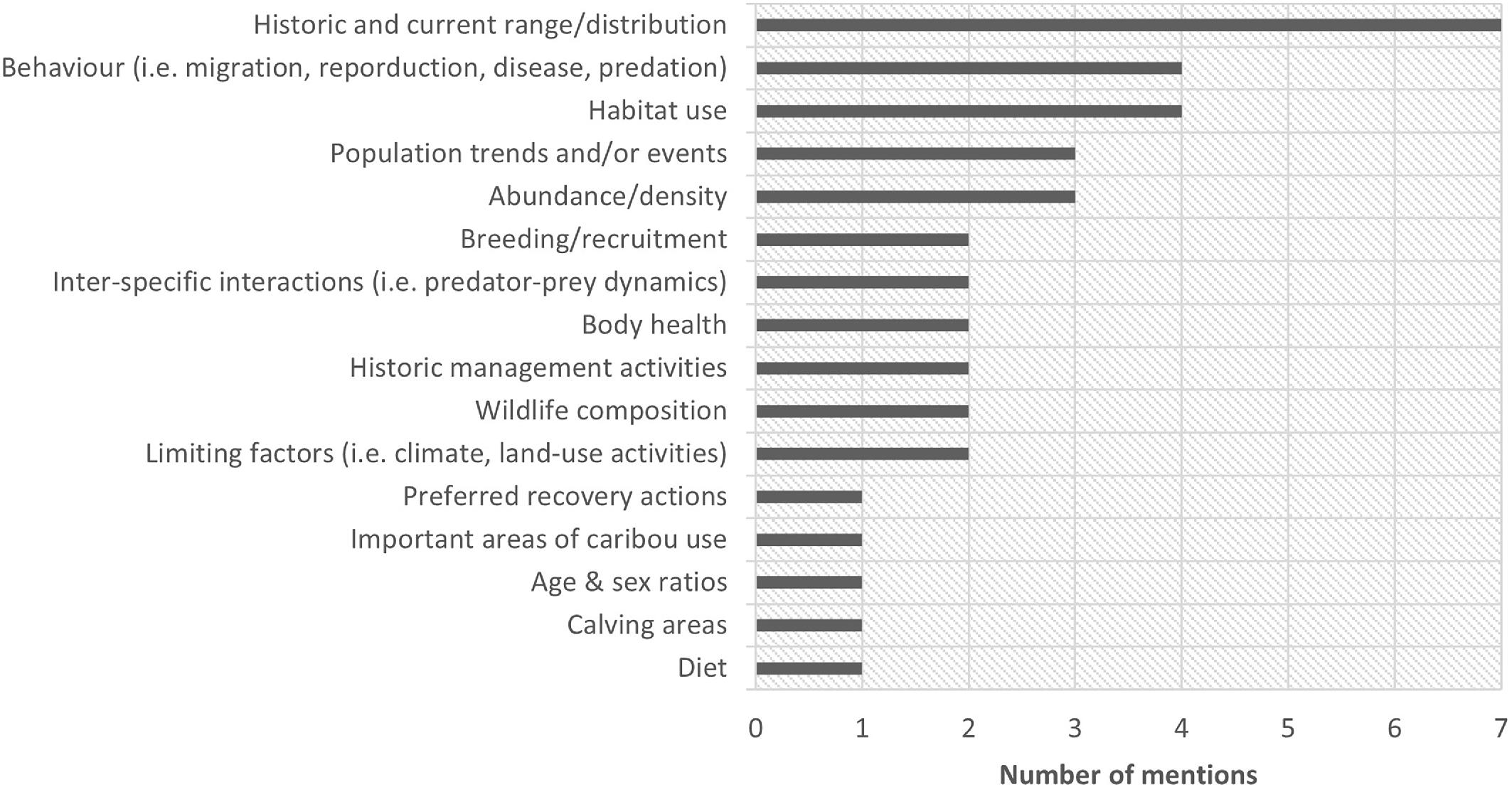

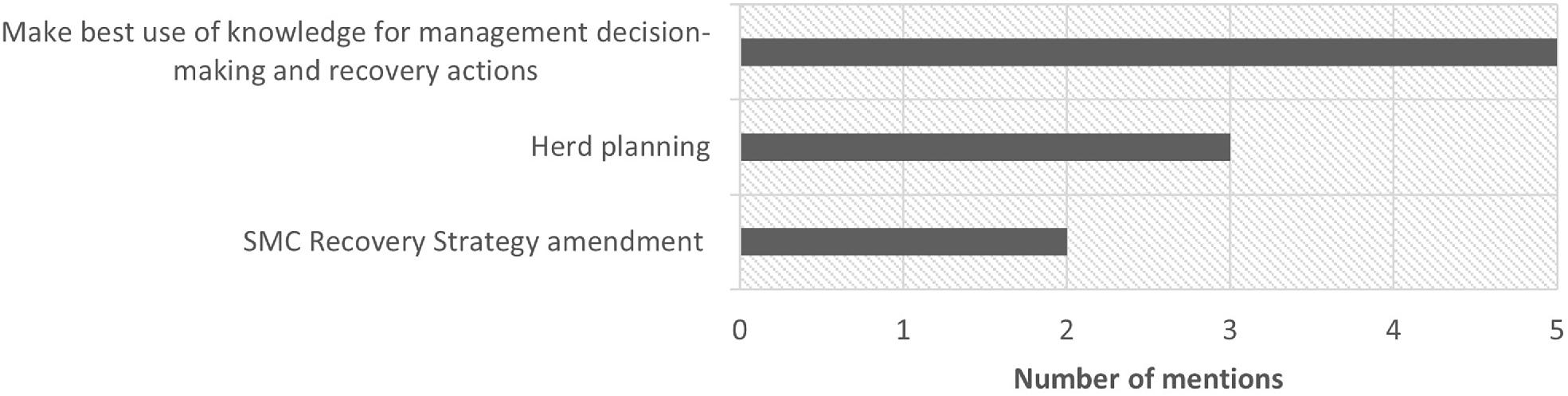

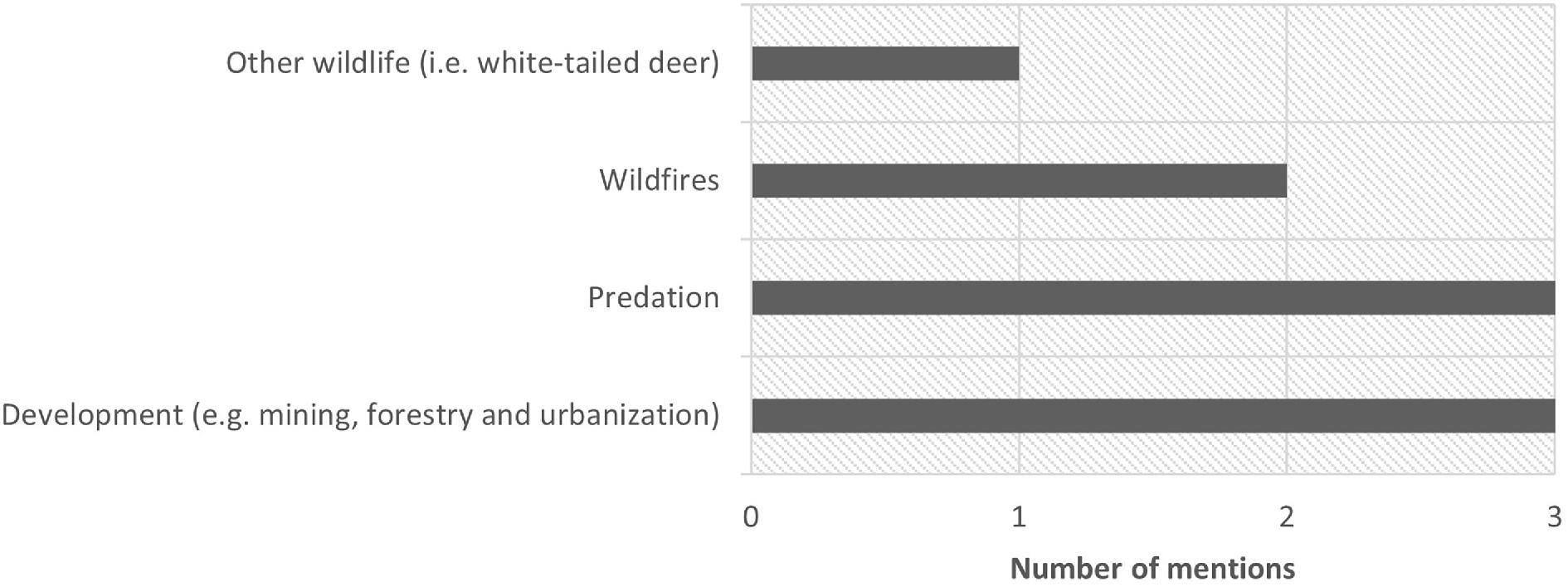

Survey of professionals

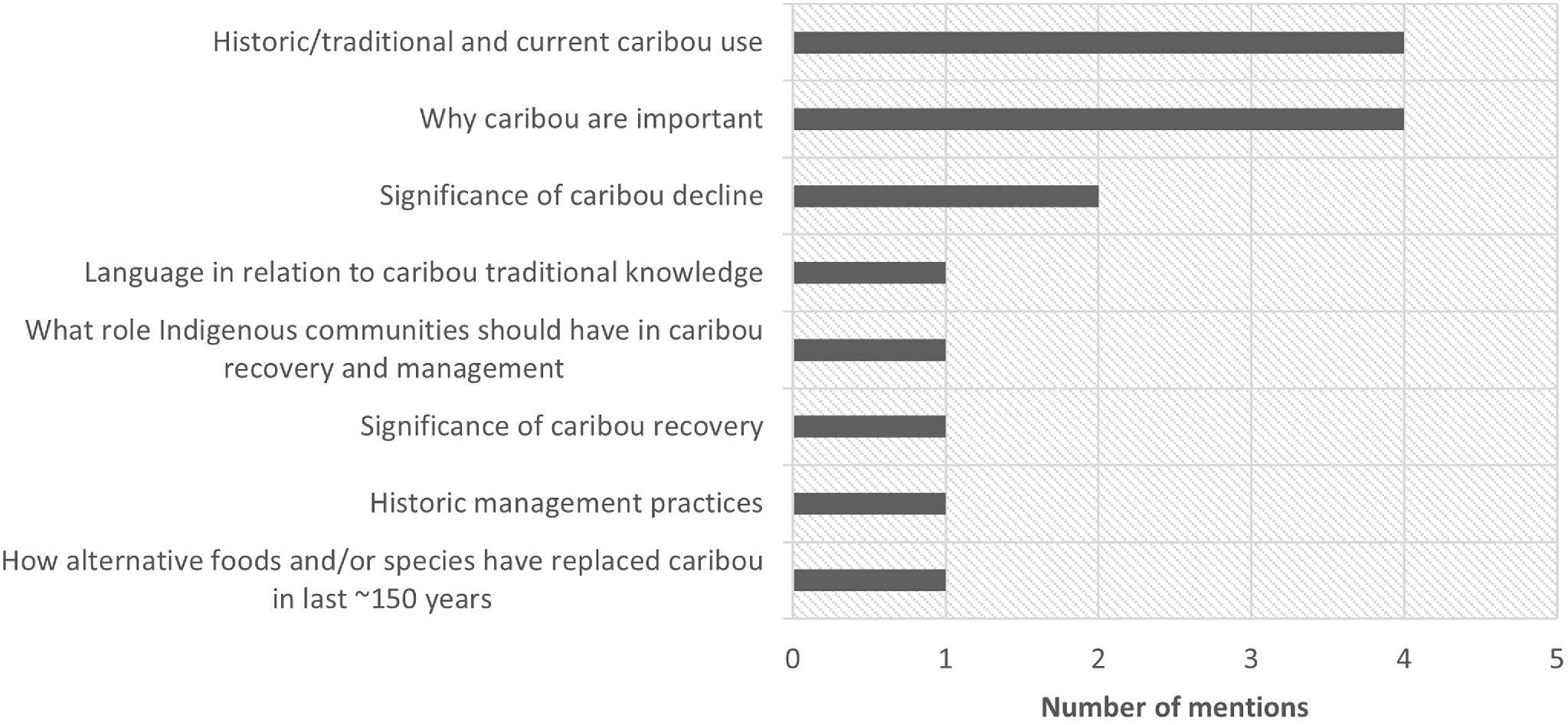

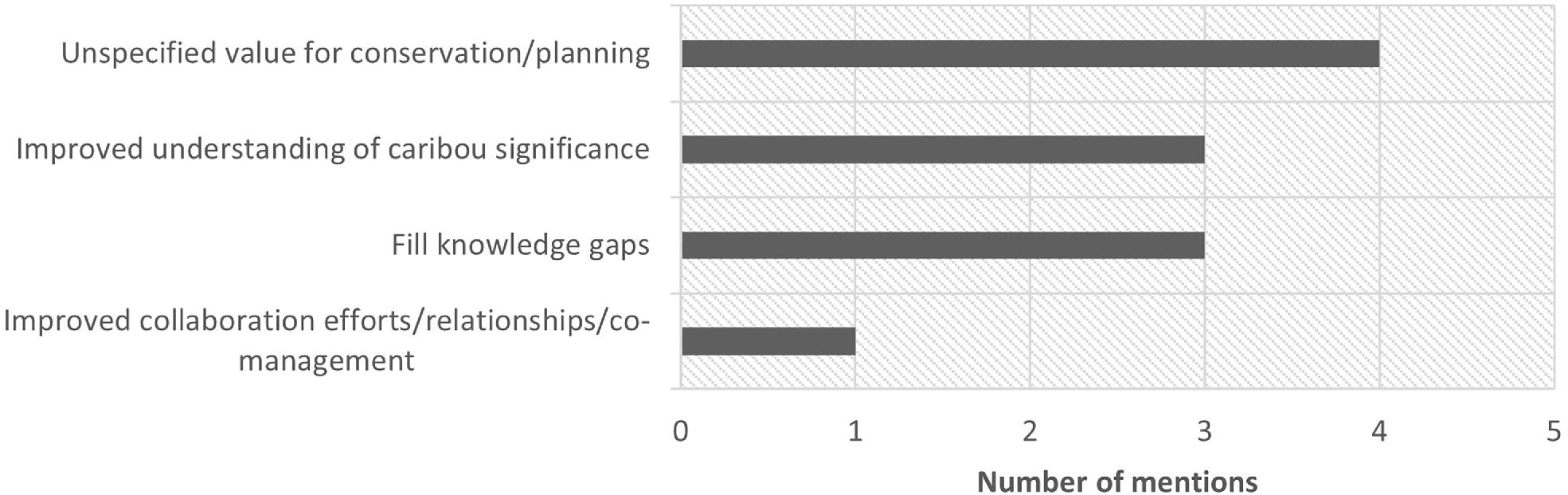

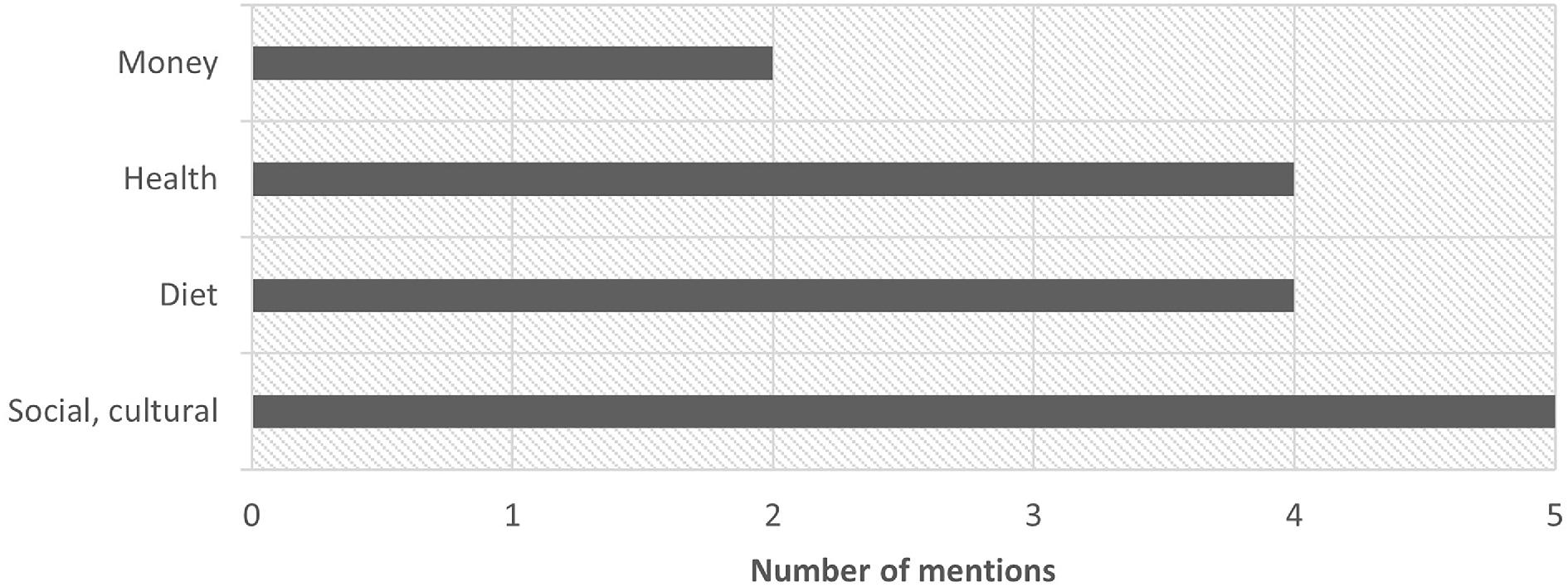

Indigenous knowledge interviews

Indigenous knowledge on caribou demographic information

“[Caribou is] probably more like a delicacy now- it's hard to come by.”-Participant 7

“[Caribou have] probably declined because I haven't seen [any]. Even when I'm hunting moose, you know, we never see them. Back in the west and back in Barkerville […] never seen any, so it's really declined.”-Participant 4

“The ones I[“ve] seen in Lhoosk'uz, they were pretty healthy. They look beautiful, just you know, not bony or anything. And at Barkerville I[‘ve] seen them- it was spring time, so they had their winter hair, so they look kinda [in] good shape and the young ones too- they seem to be ok- walking ok- so I didn't see anything wrong with them.”-Participant 5

“We'd see a couple here and there but the ones we did see they […] didn't look very healthy. It was poor but I'm pretty sure it was tick season too, they had hair patches.”-Participant 1

“I think basically in the settled areas- [the caribou] had moved away and come further out. Like out in [Barkerville] and out towards Esdilagh. And northwest of there and northeast of Quesnel and East out into the Bowron Lakes […] maybe to the southwest. I've heard of them being down like into Quesnel Lake and I haven't heard of any to the south [of there].”-Participant 7

Social-ecological knowledge on caribou

“If somebody drops off caribou, I'd be extremely happy because I have to feed my family for, however long I can. Anything like fish and moose meat but caribou, we get excited when we get caribou, because we don't get it that much.”-Participant 1

“I really believe that the caribou have a lot to teach us, if we had every[one] come out to hunt or to observe a game […] when we were hunting an animal- it brings us into [our] territory. This territory out here [Barkerville] is a lot different than our territory back in town- and so we would have an extended stay out here and we would be practicing different cultural practices. And we would be teaching all of this, [and] learning different parts of our territory with regards to different medicines and berries that we would pick on this territory as opposed to vegetation that we would find back home. And the other animals that we would hunt or gather here. That would be one of the main things that the caribou would be teaching, just by us coming out and seeking them. We would automatically have to adapt to the surroundings.”-Participant 7

“From what I've heard [caribou] was just as important as moose and deer. So, it was kind of a necessity.”-Participant 2

“[Caribou] was pretty important because that was the main herds in the area. A lot of our people, the Carrier people, that was their main food source pre-contact and they pretty much used the caribou for everything. Like for sewing for thread, the hide for making clothing and moccasins and stuff like that and the bones for tools, all that kind of stuff. When a young boy became a man he had to shoot his own caribou […] that was kind of like a coming of man ceremony. So, they would send him out in the bush and he'd have to come back with an animal and the preferred one was a caribou because there was mostly caribou back then. And this was before the moose was introduced into our area, because moose is a northern animal, so the moose pushed a lot of the caribou out of our area. Around contact times- the non-native people put out a bounty on the caribou herds in this [Barkerville] area. Similar to what they did to the Plains Buffalo and they told the non-native to just kill as many caribou as they can for themselves so they can starve our people out of the bush and […] make us come to the cities to depend on the governments and stuff.”-Participant 3

Indigenous perspectives on caribou management

“I think the starting point just started and we have no communication with whoever is trying to protect [the caribou], like through government or game warden or whoever is supposed to protect [the caribou]. There has to be a main person in the government and the main person in with the band. Right now, we need Elders- we have an Elders group here- we need to communicate with our Chief and Council, the band manager and all that. We have to be on the same page as [those] dealing with people that are trying to protect the caribou. We need to hear about it as Hunters and Elders and we have to come together and work together.”-Participant 5

“There is a system that we had back[then], pre-contact. I remember my uncle William telling me the same story when I was a young kid and he said when there's a herd of moose or a herd or elk, whatever animal you are hunting, you gotta leave the big ones, the big bull moose, because they are the ones making the babies with the momma animals right? Then you got the ones that are younger than the bigger bull moose and you gotta leave those ones behind because there are the ones that are going to take over after the big bull moose are gone. And the ones that are diseased you leave those ones, you don't shoot those ones, because those ones feed the wolves, you know. And then the ones that are in between, like the bucks and the diseased, there is more [of] those and those are the ones that you take. So that's a traditional teaching that my uncle William talked a lot [about] from Kluskus and here. So, we had a system on how we hunted them because each one was for a purpose, each animal in the herd has a purpose for the environment, so it could be equal.”-Participant 3

“I mean we as a First Nation's people only kill when it is needed. And […] we try to utilize every part of the animal. If we are to kill a wolf we use the hide for clothing or something or other and the same would be for any part of the animal that we could utilize. We would not shoot it and leave it there to die- because every animal has a spirit, every living thing has a spirit.”-Participant 7

“It's not only the wolves, it's the grizzly bears too that's getting [the caribou]. Spring time, especially. That's when they're really hungry and they go after a moose, caribou, any sight of animals. We have that problem at the ranch. We're always losing calves and our cattle to the grizzlies […] because we are up in the mountains.”-Participant 4

“There has to be some kind of process […] having respect for nature. [O]ur people respect animals and we need to do a proper ceremony if we are killing off the wolves, not killing them off but, managing them. There would need [to be] ceremonies or something that would need to be done beforehand.”-Participant 1

“I think moose population would be maintained by just native people anyways, because that's the main source of food [for us].”-Participant 1

“[Indigenous People] should have a big role in there, because it's our land and we want the best for our land, we don't want people all over. And the elders know a lot of stuff to help and they can guide other people, like how to go about the stuff instead of just sending colonizers in to do a job that maybe we would want to [do and] would benefit from.”-Participant 1

“[We need to have] more involvement with our people in that management system so that the herds can be preserved better. Because we, our people, lived with these animals for thousands of years, we kind of know how to manage them- you know- it's not like some European way of doing things, where they did it differently. [S]o they should have a lot more involvement of our people in those systems. Because it is, it was, our livelihood- but now its kind of not there anymore.”-Participant 3

“We had probably lost any traditional knowledge that we may have [had] down here with regard to this herd because they are so few and we as a people hadn't been out engaging with the animals and […] being out on the land and seeing them. But I mean traditional knowledge doesn't have to be from us. If we […] were to go and mingle with the people up in the north and learn their traditional knowledge and practices because […] no matter what First Nation we all feel that the animals have spirits, and we have the same beliefs whether we practice the same or not. We all believe that the animals have spirits and that they have to be treated with respect. They had been dealing with [caribou] for thousands of years up in the North and they are more numerous. To see how they practice their hunting and how they interact we could probably learn a lot from them even if it were just like for a hunting season to go out there and see how they practice their hunting and listen to their stories. Stories have always been a big part of our heritage and to go up and listen to the Inuit or whomever has the knowledge.”-Participant 7

“Yes, I do think that First Nation led monitoring, if this were to be made and it doesn't have to be lucrative, but for youth to know that they would have a future in this type of field and know that they have a meaningful job, it would give them something to strive for instead of something that they are forcing themselves to get up and do everyday. I feel that for the most part, a lot of First Nations would rather be out in a setting like this as opposed to sitting in a gas station or a supermarket or something in the city. To be able to get up and say I'm going to get up and go out into the bush and go and help the caribou or something or other. It gives them something to look forward to.”-Participant 7

Discussion

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

Supplementary material

- Download

- 27.11 KB

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Copyright

Data Availability Statement

Key Words

Sections

Subjects

Plain Language Summary

Authors

Author Contributions

Competing Interests

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Other Metrics

Citations

Cite As

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

There are no citations for this item