Provincial diffusion, national acceptance: the transfer of conservation easement policy in Canada

Abstract

Conservation easements (CEs) are a private land conservation (PLC) tool, with landowners voluntarily selling property rights to an outside entity (governmental or nongovernmental). Pioneered in the USA, CEs were operationalized in the late 1980s, and by 2001, legislation had swept across Canada. I asked how did subnational Canadian CE policy develop? I analyzed Hansard records and interviewed government officials, finding coercion from the Federal government and environmental nongovernmental organizations (eNGOs), with transfer being ideologically, geographically, and temporally uneven. CE legislation reveals a fundamental shift in how subnational governments were trying to enhance biodiversity conservation, specifically by legitimizing PLC and non-state partners. Interestingly, this study both confirms, and pushes back against, previous Canadian policy transfer studies. I found a lack of formal subnational policy networks and an increased role of subnational policy innovators unlike previous studies, while the substantial U.S. influence align with older policy cases. ENGOs were the most active proponents to push for CE legislation, not policymakers or foreign states. Ultimately, Canadian federalism creates unique subnational policy arenas that require further study to understand the movement of conservation policy, especially with the crises of biodiversity and climate.

Introduction

Modern biodiversity conservation is at an inflection point. The Living Planet Report from the World Wildlife Fund estimates that biodiversity has decreased by 69% in the review of 4392 species (WWF 2022). This report also signifies that North American species have declined by 33%. With extinction rates nearly 1000 times higher than natural, significant drivers include habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, and natural resource exploitation (Díaz et al. 2019). The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) recognized the need to expand protected areas, with Canada becoming the first industrialized nation to ratify (UN 1992). Most countries recognized this and signed the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, with Target 3 reinforcing that at least 30% of terrestrial and marine ecosystems need to be conserved by 2030 (Watson et al. 2023).

As the worlds’ second largest country with a relatively small, but highly concentrated populace, Canadian biodiversity conservation objectives often span across public land and private property (Krauss and Hebb 2020). In this context, the central federal legislation is the Species at Risk Act (SARA), which, among other things, protects biodiversity on federal lands (Olive 2014). Provinces are empowered to create their own biodiversity laws, which has resulted in an uneven legislative mosaic across Canada. At the time of writing, six of the thirteen provinces and territories have specific species-at-risk legislation (Ray et al. 2021), reinforcing the asymmetry of Canadian biodiversity legislation and the necessity for private land conservation (PLC) (Pittman 2019; Reiter et al. 2021).

Recently, the Canadian Government has sought to mitigate these crises, with a central policy being the “30 by 30” pledge, aiming to conserve 30% of Canada's land and water by 2030 (Canada, Environment and Climate Change 2022). As of 2021, Canada had 13.5% of land and 13.9% of its territorial waters protected through a variety of structures, partnerships, and policies (Canada, Environment and Climate Change 2021). While this is substantial, the Canadian Government must protect 16.5% and 16.1% more, respectively. Additionally, federal land is scarce in the more ecologically diverse, privately owned, and endangered southern provincial landscapes (Krauss and Hebb 2020).

This presents both challenges and opportunities for governments (national and subnational), environmental non-governmental organizations (eNGOs), and private landowners to address conservation in Canada. Moving forward, conservation on private land is a clear pathway to reaching 30%. Most subnational jurisdictions have established legislation allowing PLC tools, with a popular choice being conservation easements (CEs). These are voluntary agreements that seek to entice landowners to place restrictions on their properties for conservation benefits (Rissman 2013).

While policy diffusion has been widely studied across the realms of sociology (Dobbin et al. 2007) and political science (Marsh and Sharman 2009), it has yet to be widely investigated in a purely Canadian context (Boyd and Olive 2021). Investigating the spread behind CE policies in subnational governments provides an opportunity to illuminate both an understudied conservation device (CEs) and an understudied framework (policy diffusion/transfer), while seeking to understand the complex relations between individuals, institutions, and ideas of how conservation policies are developed. My research questions are: How did Canadian subnational governments develop CE policy? To what extent can it be explained by policy transfer and diffusion?

Literature review

Policy transfer

Policy transmission, or the process of institutions exchanging knowledge and policies, show how information can be transmitted, and how such dissemination takes place (Dolowitz 2003). One key aspect of such transmission is policy transfer. This is the movement of knowledge from one setting to another. Transfer is often more focused around the roles of agency and agents (Boyd and Olive 2021). Policy migration occurs due to ideological changes, normative tensions, copying successful policies, and seeking to gain prestige (Dobbin et al. 2007).

Policy transfer mechanisms that enable migration include learning, and imitation or mimicry (Boyd and Olive 2021; Marsh and Sharman 2009). Learning is the process of new information changing beliefs in political agents (Dobbin et al. 2007). Governments gather information about foreign policies to produce more effective outcomes, however, the extent of learning can lead to varying degrees of emulation (Marsh and Sharman 2009). Imitation or mimicry is the copying of foreign models based on prior policy. Such actions may seek to gain support or legitimacy from other nations with similar (or the same) policies (Marsh and Sharman 2009). Often, Canadian policies are influenced by the U.S. due to the geographic proximity, socio-political similarities, and shared history (Hoberg 1991; Harrison 2012; Boyd 2017). Just as pollution and goods flow across borders, so too does policy and knowledge.

eNGOs and conservation easements

Land trusts have recently become a key participant in conservation, specifically as charitable eNGOs that use CEs to protect private lands (Parker 2004; Gerber and Rissman 2012; Capano et al. 2019). Land trusts and CEs have a complex history, often using handshake agreements with landowners throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries before legislation. They rapidly grew during the later 20th century as CEs gained popularity in the United States throughout the 1980s and 1990s (Gerber and Rissman 2012). Land trusts can keep governments at arm's length and can operate independently, attracting landowners who may be suspicious of governmental actions and policies. They overwhelmingly rely on CEs as they consider current land-use planning and regulations to be inadequate, politically charged, and lacking in tangible private conservation benefits (Gerber and Rissman 2012).

CEs are legally binding agreements between voluntary private landowners and easement holder, including eNGOs or a subnational government if legislation allows. They are focused on the restriction of specific property rights for conservation benefits but can include aspects like requiring public access (Wright 1993). They are flexible, involving some rights being sold to the easement holder for an agreed-upon time, usually in perpetuity (Parker and Thurman 2019). Most “run with the land” (in perpetuity), uniquely transforming a contractual right to a property right on title and existing regardless of landowner change (Parker 2004). Restrictions can include limiting development, resource extraction, or agricultural conversion (Parker and Thurman 2019). CEs provide an effective tool to navigate increasingly politicized debates around private property and conservation science, as they focus on attracting voluntary participation (Merenlender et al. 2004).

A review of global private conservation literature found several dominant themes, including a clear emphasis on CEs as the primary instrument for PLC, with property rights being overwhelmingly discussed (Capano et al. 2019). Additionally, a more recent review found that PLC studies in the U.S., with Australia, South Africa, Canada, and Europe (broadly) overwhelmingly focus on CEs (Kemink et al. 2021). Both reviews showcase that PLC in these countries—which all exhibit similar property regimes and colonial histories—rely heavily on CEs. CEs have risen in popularity since their increasing use in the United States during the 1980s. The estimated growth percentage for CEs from 1990 to 2010 was + 1588%, resulting in an additional 12 599 363 acres protected in the U.S., vastly outpacing other conservation instruments (Parker and Thurman 2019).

Theoretical predictions

Based on literature surrounding conservation policy, I expected the following predictions (or a combination) for subnational CE policies:

1.

Jurisdictions imitated earlier CE legislation through a process of policy transfer.

2.

Jurisdictions located geographically close to one another adopted CE policies through policy mimicry.

3.

Jurisdictions learned through interactions with other states to develop CE legislation.

Methods

This study analyzed all 13 Canadian subnational jurisdictions. The methods are similar to case studies provided by Boyd and Olive (2021), one of the only projects to focus on Canadian policy diffusion. Specifically, the chapters by Olive (2021) and Besco (2021) provided insight into the process of analyzing subnational policies by using legislation and the Hansard, which is the transcript for parliamentary government debates, speeches, questions, and procedures in Commonwealth countries, and draw on policy tracing through document analysis. I began by focusing on finding and analyzing CE legislation for each subnational jurisdiction, then analyzed the Hansard debates surrounding the creation of such legislation. I inductively coded each jurisdictions Hansards to understand how government officials, opposition politicians, and other experts (eNGO representatives, outside experts, etc.) were supporting and/or pushing back on the legitimization of CEs. Additionally, I sought to interview individuals who were connected to the legislation to enhance my analysis, as it could not be assumed that the Hansard transcripts would capture all lobbying and influence impacting CE legislation.

To find legislation, I searched subnational government websites using keywords such as “conservation easement”, “private land conservation”, or “biodiversity conservation”. This allowed me to quickly find the governing legislation and trace the time periods for tracking down Hansard transcripts. I then coded each document to produce categories which included: the name of the PLC tool (CE, Conservation Covenant, Conservation Agreement, etc.), the purpose for the CE, which political party introduced the legislation, whom may hold a CE, if the legislation was standalone or amended, and the Ministry responsible for oversight. As legislation is unique to its jurisdiction and focuses on fundamental aspects of CEs, this did not provide adequate data to see cited influences but allowed legislative differences to become apparent. Additionally, I relied on a now-outdated review of CE policies from Atkins (2004) for verification.

To find Hansard transcripts, I searched for the first, second, and third readings of each subnational CE bills publicly available through government websites, emailing government employees if I ran into difficulty. Most debate took place during the second reading. Barring two provinces, Quebec (QC) and Prince Edward Island (PEI), I succeeded in finding the records on my own. QC did not have English translations, requiring assistance from a provincial employee. I used Google Translate to translate these files into English. PEI does not have digitized copies of Hansards until 1988 but provided an audio file of the pertinent readings.

After coding each cited influence, I then proceeded to analyze the jurisdictions legislation to see if there was direct imitation, including the legislations name, features, and other legislative aspects. I also coded passages that discussed CEs to track the context for CE debate. I kept track of individuals, groups, and governments being discussed, how often, and in what context to build categories. This could vary widely from local conservation groups, international eNGOs, other Canadian subnational governments, and foreign states (seeTables 1–3).

Table 1.

| Jurisdiction | Legislation | Name of tool | Total eNGO mentions | Total other jurisdiction mentions | Total other mentions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prince Edward Island (PEI) | Natural Areas Protection Act (1988) | Conservation Easement or Covenant | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Northwest Territories (NWT) | Historical Resources Act (1988) | Historic Places Agreement | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nunavut (NV) (formerly NWT) | Historical Resources Act (1988) | Historic Places Agreement | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador (NFL) | Historic Resources Act (1990) | Conservation Easement or Covenant | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yukon (YK) | Environment Act (1991) | Conservation Easement | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| Ontario (ON) | Conservation Lands Act (amended 1995) | Conservation Easement or Covenant | 20 | 30 | 5 |

| British Columbia (BC) | Land Titles Act (amended 1995) | Conservation Covenant | 28 | 0 | 4 |

| Alberta (AB) | Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act (amended & transferred to the Alberta Land Stewardship Act in 1995) | Conservation Easement | 39 | 14 | 3 |

| Saskatchewan (SK) | Conservation Easements Act (1996) | Conservation Easement | 14 | 2 | 7 |

| Manitoba (MB) | Conservation Agreements Act (1997) | Conservation Agreement | 12 | 10 | 2 |

| New Brunswick (NB) | Conservation Easements Act (1998) | Conservation Easement | 14 | 2 | 0 |

| Nova Scotia (NS) | Conservation Easements Act (2001) | Conservation Easement | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Quebec (QC) | Natural Heritage Conservation Act (2002) | Nature Reserve; Conservation Servitude | 20 | 24 | 8 |

To enhance and support my content analysis, I sought interviews with officials involved in CE legislation, emailing 21 individuals from every subnational jurisdiction. The response rate was low, which is not surprising considering most legislation is over 20 years old. However, I interviewed eight participants covering six jurisdictions including the Federal government. While this is a low response rate, these individuals were very knowledgeable, having worked closely to pass this legislation (including a former Minister), and provided valuable information that reinforced findings from the content analysis. Interview questions focused on the participants’ knowledge of CE legislation, if they knew of any policy transmission, and their overall views of CEs as conservation tools. I inductively coded these interview transcripts, creating categories that included: why they thought CEs were important for PLC, why (to the best of their knowledge) did their government support and pass CE legislation, who was supporting the legislation, who was against it, where did they see influence and lobbying coming from, and was there any collaboration with eNGOs, outside experts, or other jurisdictions to create or support CEs. All interviews were conducted with approval from the University of Toronto's Ethics Board (protocol #43715).

Keeping with Boyd and Olive (2021), I followed Hall's typology of policy learning framework (1993), which focuses on differentiating orders of learning (first, second, third) to examine policy transfer. This framework allows a researcher to respond to various policy shifts. For example, first-order shifts may change details or settings, second-order shifts focus on changing acceptable instruments, and third-order shifts provide systemic changes to ideas and ideologies underpinning goals (Hall 1993). This analysis was useful after inductive coding, which provided the ability to order CE legislation into different orders. Furthermore, Hall's typology provided a lens to understand the implications of lobbying by outside jurisdictions and organized non-state interests from a theoretical underpinning.

As I was specifically concerned with jurisdictional transfer, I did not attempt to isolate or specify diffusion mechanisms outside of my initial predictions. This was outside the scope of my research and would require more data to unravel the (likely multiple) mechanisms at work, as Berry and Berry note (2018). Future research could address this, with targeted interviews and media analysis to augment findings.

Data and results

Jurisdiction breakdown

Across Canada, each jurisdiction has legislation which allows for CEs. Tenhave explicit legislation which directly provides a framework for their use. Three having historic resource laws that do not directly discuss CEs but allow for the potential conservation of private land (see Table 1 below). Table 1 showcases each jurisdiction's influences from Hansard analysis, and separated into three categories (“eNGOs”, “other jurisdictions”, and “other”). For example, in 1995, Ontario (ON) had 30 “other jurisdictional” citations, with 20 “eNGO” and 5 “other”; while Alberta (AB) had a majority of “eNGO” citations (39) and a relative scarcity from “other jurisdictions” and “other” (14 and 3, respectively).

Additionally, almost all provinces have explicit CE legislation, with Newfoundland and Labrador (NFL) being the only outlier. Yukon (YK) is the only territory to have legislation that explicitly discusses CEs. Both Northwest Territories (NWT) and Nunavut (NV) have Historic Resources Acts, which may allow for protections on private land but are not explicit. Also, both have no Hansard data discussing CEs, making it difficult to understand how PLC could work. This may be due to the historical connection these territories have (NV was created from the NWT in 2003) and their shared lack of large-scale private property.

Prince Edward Island (PEI)

PEI has the earliest legislation in Canada allowing PLC. The Natural Areas Protection Act allow for CEs to be held by land trusts and conservation groups across the province. PEI also had one of the lowest mentions of actors, groups, or governments surrounding the debate of this legislation. A single eNGO, the Island Land Trust, was mentioned once, and Environment Canada was the only other group mentioned.

Northwest Territories and Nunavut (NWT and NV)

As of this writing, both territories do not have explicit legislation for CEs and, like NFL, also rely on the provincial Historic Resources Act for preservation of historic places. As there is no definition for historic places, this does not preclude potential biodiversity conservation through the Acts but showcases a lack of focus on PLC. As such, Hansard data was deficient in discussing actors, groups, or governments.

Newfoundland and Labrador (NFL)

As discussed above, NFL is unique due to their Historic Resources Act, which potentially allows for PLC due to the broad language surrounding the Act's definition of “historic resources”, which includes archeological, cultural, and natural values. Having not originally been focused on the creation of CE policy, Hansard data are deficient of any mention of eNGOs, other jurisdictions, or individuals in support of CEs.

Yukon Territory (YK)

The Yukon stands alone as the single territory to have specific CE sections in their Environment Act. Other governments were the most widely cited examples with Canadian provinces being broadly mentioned twice. BC, PEI, and the United States were all specifically discussed. Uniquely, other actors that were not eNGOs are the second largest group to be mentioned. Local municipalities and businesses were both mentioned twice. First Nations were discussed once, interestingly as the only instance that Indigenous Peoples were explicitly discussed. Finally, eNGOs that were discussed include conservation groups (generally) (2), the Yukon Trappers Association (1), and the Association of Yukon Communities (1). A follow-up interview confirmed that the Yukon Government had looked at other jurisdictions for CE inspiration, reinforcing the provincial and U.S. influences.

In the Yukon, we did look across… We always look across jurisdictions and even in other countries to find the best practices, the current practices…So, I know at the time (of the Environment Act), looking across the country, other jurisdictions were struggling with protection of land habitat and things, and so that was why it (CE policy) was built in at that time.—Participant 4

Ontario (ON)

Ontario was a PLC policy innovator. They had CE policy created after passing the Conservation Land Act in 1988, but only the Ontario Heritage Foundation (a provincially affiliated group) was able to hold CEs, limiting their scope substantially. ENGOs were able to hold CEs after the Act was amended in 1995. Ontario had the second largest number of groups, individuals, and governments cited in support. Uniquely, they are part of a minority of provinces where politicians cited other jurisdictions more than eNGOs. Broadly, U.S. states (7) were the most highly mentioned with the states of Maryland and Colorado being each mentioned twice, with others including Northeastern states (Massachusetts, Vermont, Maine), California, and Texas. The only explicit Canadian province mentioned was BC (3), with mention of provinces across Canada being discussed once. Ontario politicians discussed various provincial departments and talked about examples in Europe once as well, specifically an example in Britain. While slightly less discussed, eNGOs still made up a sizable percentage of citations. Most mentioned included the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) (3) and the Escarpment Biosphere Conservatory (2).

British Columbia (BC)

BC's Land Titles Act authorizes the placement and protection of private land through conservation covenants under section 219. Analyzing Hansard data revealed that eNGOs were the overwhelmingly discussed actors during parliamentary debates. Specifically, Ducks Unlimited (DU) (12 mentions), Nature Trust of BC (4 mentions), and Island Trust (3 mentions) were the most cited groups in defence of protecting private land through CEs. No Canadian or foreign governments were mentioned. What stands out is the lack of mentioning other governments, as only NFL is the other province to not cite other jurisdictions.

Alberta (AB)

Alberta's Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act (EPEA) was the first legislation to include provisions for CEs. The EPEA was amended in 2009, with CE policy transferred to the Alberta Land Stewardship Act (ALSA). Hansard data shows that Alberta narrowly had the most groups discussed in support of CE legislation. ENGOs were also the most highly cited proponents. The NCC and Ducks Unlimited were the top two cited organizations (14 mentions and 9 mentions, respectively). Interestingly, an NCC employee was repeatedly named as a chief advocate and expert. Alberta also mentioned other governments 14 times. These mostly included other Canadian provinces such as PEI (3), ON (2), MB (1), NS (1), BC (1), and QC (1). Albertan politicians also discussed municipal counties, U.S. states, and Europe nations as successful CE examples.

Saskatchewan (SK)

The Hansard data for Saskatchewan's Conservation Easement Act lacked citations for actors and influences compared to other jurisdictions. While eNGOs again made up most of the cited actors, they were only mentioned once or twice. Ducks Unlimited, Saskatchewan Wildlife Federation, and NatureSask were the most discussed with each having 2 citations. No foreign governments were discussed, putting Saskatchewan in a minority of jurisdictions that did not provide other places as examples. A follow-up interview with a former Environment Minister showed that policymakers were acutely aware of legislation in the US, and how CEs were beneficial for eNGOs with conservation goals, even though they did not mention them.

Me and the staff were aware of them (CEs) and how they worked in the states… we thought this would be an excellent way to secure our vanishing landscape on private lands. We came up with a formula in collaboration with NGOs like Sask. Wildlife Foundation, Ducks Unlimited, Nature Conservancy.—Participant 5

Manitoba (MB)

Manitoba's Conservation Agreements Act data revealed that eNGOs were again the most cited group, with Ducks Unlimited (3), Manitoba Habitat Heritage Corporation (2), and the Union of Manitoba Municipalities (2) being the top three groups. Of notable interest is that politicians utilized a plethora of Canadian governments in support as well. These include AB (1), BC (1), SK (1), PEI (1), NS (1), ON (1), YK (1), and even mentioned their own Department of Natural Resources once. U.S. states were also broadly mentioned twice as evidence of successful PLC policies.

New Brunswick (NB)

ENGOs were the most cited group in support of legislative debates for NB's Conservation Easement Act. The Conservation Council of New Brunswick and Nature Trust New Brunswick both were the most mentioned in three instances. Following them, Ducks Unlimited, and the Land Conservatory both were cited twice, with the Eastern Habitat Joint Venture and the Conservation Trust both discussed once. Vague “other provinces” were mentioned twice.

Nova Scotia (NS)

Compared to other jurisdictions, NS’ Conservation Easements Act had relatively little legislative discussion surrounding various actors. While other governments were the most mentioned, this only totalled 4, with ON, PEI, Florida, and the U.S. each receiving a single mention. Conservation eNGOs were mentioned twice at-large and the Nova Scotia Nature Trust was explicitly cited twice.

Quebec (QC)

Quebec is unique as they follow a Civil Law, unlike other Canadian jurisdictions. Having passed the Natural Heritage Conservation Act, the province explicitly connected conservation to “safeguarding the character, diversity, and integrity of Quebec's natural heritage” (Natural Heritage Conservation Acts. 2., 2002). Adding to their uniqueness, Quebec provides three different PLC tools which include natural reserves, servitudes réelles de conservation and servitudes personnelles de conservation (Ministère de l’Environnement 2018). Like Ontario, Quebec also mentioned more governments than eNGOs in support of CE legislation. ON (5) was the most cited with BC (4), Bermuda (3), and the United States (4) being the next most discussed. Other jurisdictions mentioned included France (2), Vermont (1), Florida (1), California (1), and Germany (1). ENGOs were the second most mentioned group with Ducks Unlimited (3) being the most cited.

Federal Government

On the surface, the Canadian Government did not appear to factor into subnational debates. However, there is evidence that suggests they were actively seeking to coerce jurisdictions. Interview data suggests tax law changes and the enactment of the Federal EcoGifts Program provided financial incentives and acknowledgement for CEs (Canada, Environment and Climate Change 2023). The EcoGifts Program was established in 1995, coinciding with a surge in CE legislation creation. An interview with a former federal employee alluded to coercion by discussing the timing and benefits as favouring subnational governments considering CE legislation. They also discussed how the U.S. land trust accreditation framework was influential in the establishment of a similar Canadian framework, reinforcing how CE policies were inspired via foreign legislation.

It's not a surprise that the Ecological Gifts program and provincial legislation started to be put in place…through that time period.—Participant 1

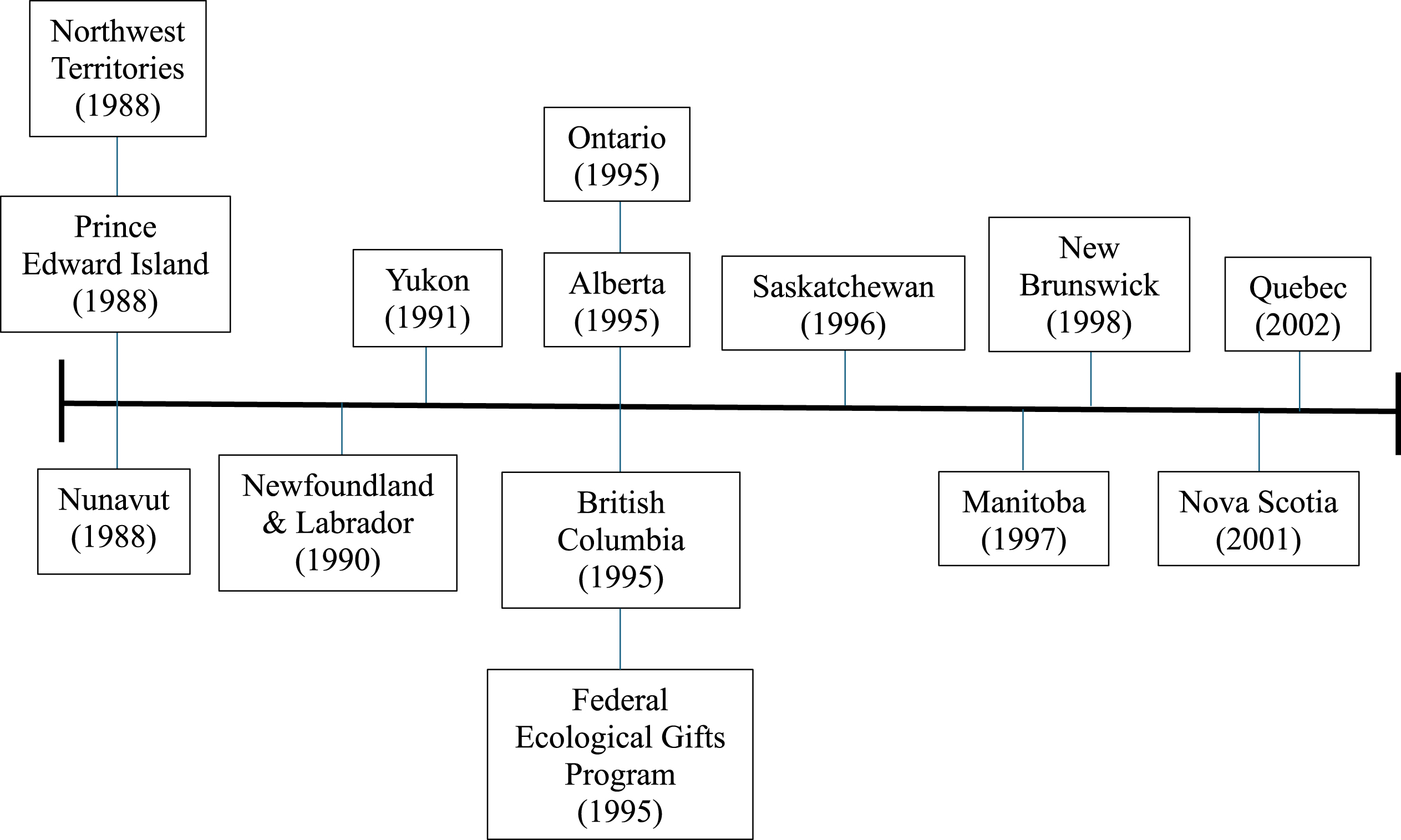

Timeline

Canadian CE legislation can be characterized as three distinct phases. The first occurring from 1988 to 1991, with PEI, NWT, NV, NFL, and YK having the first legislation enabling CEs. From 1995 to 1997, there is the largest creation of CE legislation as ON, BC, AB, SK, MB, and the Federal Ecogift program are enacted. Finally, from 1998 to 2002, the provinces of NB, NS, and QC were the last jurisdictions to produce CE legislation. See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

eNGOs and other jurisdictions

As noted in Table 1, eNGOs were mentioned in the Hansard numerous times during policy formulation and adoption. The most named eNGO included (1) Ducks Unlimited, (2) conservation organizations (broadly), and (3) NCC. See Table 2. Of specific interest is the relative wide-ranging consistency that almost every jurisdiction had some discussion of an eNGO, either specifically named or broadly mentioned. The largest four provinces by geography and population (AB, BC, ON, QC) all mentioned the top three eNGOs and acknowledged influence from regional organizations.

Table 2.

| eNGO | # Citations | Jurisdictional breakdown |

|---|---|---|

| Ducks Unlimited (DU) | 32 | BC (12), AB (9), SK (2), MB (3), ON (1), QC (3), NB (2) |

| Other Conservation Organizations | 21 | BC (1), SK (3), MB (1), ON (3), QC (4), NS (2), NB (2), YK (2) |

| Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) | 19 | BC (1), AB (14), ON (3), QC (1), |

In addition to eNGOs, other provinces and U.S. states were mentioned in Hansards (see Table 3). Other jurisdictions in relation to CE legislation were the second most mentioned group. Within this category, the most cited included: (1) U.S. states (broadly), (2) ON, and (3) a three-way tie between Canada (broadly), BC, and PEI. While the geographic spread of these citations was again uneven, it is worth mentioning that Ontario and Quebec were heavily focused on U.S. states to support legislation. Politicians in both provinces cited specific states as successful CE examples.

Table 3.

| Other governments | # Citations | Jurisdictional breakdown |

|---|---|---|

| USA (broadly) | 16 | AB (1), MB (2), ON (7), QC (4), NS (1), YK (1) |

| Ontario | 9 | AB (2), MB (1), QC (5), NS (1) |

| Canada (broadly) | 6 | ON (1), BC (1), NB (2), YK (2) |

| British Columbia | 6 | AB (1), MB (1), ON (3), YK (1) |

| Prince Edward Island | 6 | AB (3), MB (1), NS (1), YK (1) |

Ontario being the second most cited is not surprising due to its large population, economic superiority, and being home to the Federal government. Interestingly, the greatest mentions of Ontario come from the neighbouring province of Quebec. Most of these mentions discuss the progress Ontario has made and how the “Anglo-Saxons” are outpacing the efforts of Quebec. The three-way tie is interesting as well, revealing that provinces were discussing the state of subnational CE legislation at-large. Singling out both BC and PEI is not surprising as both were early enactors of CE legislation.

Obviously Canadians look to the border and say, “Hey, you know you've got that tool”, and one need not only look at the US Land Trust and conservancies—Participant 1

Lastly, other actors beyond eNGOs and subnational jurisdictions were mentioned in Hansards. While 8 of the 13 jurisdictions did mention a variety of others, these were mainly potential CE holders (landowners or businesses), experts and reports (often affiliated with a major eNGO) or consulting local counties and various subnational ministries. Uniquely, there was mention of international summits in Quebec as promoting global conservation efforts. Also, the Yukon was the only jurisdictions that acknowledged their consultation with Indigenous Nations.

Discussion

Legislation does not manifest in a vacuum. However, the transmission of Canadian CE laws was politically, geographically, and temporally uneven. The 1990s was the key decade, leading to 8 of the 13 subnational jurisdictions either amending existing laws or passing new ones, regardless of political leadership. Most provinces (6) opted to create new explicit legislation, often named “Conservation Easement Act” or some variation. A small group (4) amended previous legislation to allow for CEs to be included in entrenched law. Finally, a smaller minority (3) had existing legislation which provided a potential avenue for CEs but has not been updated.

The transmission of CE policy

1.

Prediction: Jurisdictions imitated earlier legislation through a process of policy transfer.

I predicted CE policy might be imitated from earlier legislation. There is evidence that policy transfer may have a temporal element and focused on prior laws from subnational governments (such as BC, PEI, and various U.S. states). Logically, there should be evidence of increasing jurisdictional citations for later adopters of policies, as opposed to early policy innovators. While this was mostly true as early adopters (PEI, NWT, NFL) did not mention other jurisdictions, there was one outlier. The Yukon mentioned BC's easement policy. However, this predates BC's amendment to the Land Titles Act. Interviewing a Yukon government employee did not yield an answer, and future research could explore this.

Late adopters did show an increasing cascade of citing other jurisdictions, albeit with some inconsistency. While Ontario, Alberta, Manitoba, and Quebec did cite many other jurisdictions; Saskatchewan, NB, and NS did not. This is interesting because both the timing and geographic location of these provinces do not show imitation from neighbours or previous policies. Most jurisdictions referenced other places with successful CE policies as supporting evidence. Governments that were cited for having prior legislation included Ontario, BC, PEI, showing domestic mimicry, and U.S. states (generally) via international inspiration.

Ontario was the highest cited province in Canada by other jurisdictions, which seems logical due to their large land base and population size. In addition to being home to the capital of Canada, Ontario also is more connected to the U.S. via culture and trade, reinforcing avenues for policy to migrate across borders. BC was cited by Ontario, Alberta, Manitoba, and the Yukon for having provided an example of successful CE legislation. As one of the largest western provinces, it would make sense that BC be discussed by similar sized jurisdictions, especially as their mountainous landscape pushes development into valleys and riparian areas. Alberta, Manitoba, NS, and the Yukon all mentioned how PEI had existing laws which provided more opportunity for landowners and eNGOs to conserve private land. PEI is the smallest province in Canada, geographically isolated on the Atlantic coast, with a relatively small population base and high levels of private land, making them a unique case study for CE policy.

U.S. states were the largest group to be broadly cited and discussed. Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, NS, and the Yukon all explicitly discussed U.S. legislation as successful policies. The focus on the U.S. is not unusual, as CE laws were popularized in the 1980s by some states, with other policy studies finding their influence. It also makes sense for eastern jurisdictions to look to the U.S. As the two most populous provinces, Ontario and Quebec draw more similarities with U.S. states compared to provinces with smaller populations and less land.

Because the Americans are certainly, definitely (using CEs)—this is where part of our research comes from, a major part.—(Legislative Assembly of Ontario, 1991)

2.

Prediction: Jurisdictions located geographically close to one another adopted CE policies through policy mimicry.

It is possible to see a few examples of policy mimicry between neighbouring jurisdictions, but there is an overall lack of geographic connection. Jurisdictions did mention neighbouring governments in support of proposed legislation, but this was occasional. For example, Alberta did discuss BC's successful policies, while Ontario and Quebec both went into depth about various U.S. state policies, specifically referencing New England states such as Maine, Maryland, and Vermont.

There is no single place where a jurisdiction cited all neighbours, or only neighbours were cited. For example, while PEI was the most highly cited Maritime province, this is also present in western Canada, with Saskatchewan failing to cite any jurisdiction by name in support of their proposed CE legislation. The only constant when looking for a geographic trend is the inconsistency of neighbourly citations.

3.

Jurisdictions learned policy through interactions with other states to develop CE legislation.

Policy learning did appear for some jurisdictions that cited others. As previously shown in Table 3, the top jurisdictions included: (1) the USA (broadly), (2) Ontario, and (3) BC, PEI, and Canada (broadly). Having politicians looking beyond their provinces’ borders and discussing other provincial and foreign policies is direct evidence that external legislation was being analyzed by most jurisdictions. As previously discussed, it makes sense for U.S. ideas to flow to Canada for a variety of social, economic, and political connections.

However, the largest group to be cited in support of CE policies was surprisingly not other jurisdictions, but conservation organizations. Every jurisdiction that had specific CE legislation repeatedly brought up local, regional, and/or transnational eNGOs that supported increasing PLC. Not only that, but the frequency of citations far outpaced any other category. It appears that Canadian CE legislation was most directly influenced by a collection of eNGOs, who were dedicated to the expansion of PLC through a lens of private property and voluntary landowner support.

Coercion from above and below

Canadian subnational CE legislation was largely coerced by top-down and bottom-up forces, specifically, the Federal government and eNGOs. Both groups sought to entice provinces into enhancing PLC. With historic U.S. examples, Canadian provinces were influenced by vertical forces, ultimately spreading CE policies across the country.

The indirect coercion from above is evident through the Ecogifts program, which provided federal tax relief and recognition to CEs. This program began in 1995, seemingly coinciding with the most active period of CE legislation for Canadian provinces, and as of 2022, has protected over 1697 sites, totaling 216 000 hectares and over 1 billion dollars in tax incentives (Canada, Environment and Climate Change 2023). By modifying the Canadian Income Tax code and the Quebec Taxation Act, the Federal government created financial incentives for voluntary landowners to protect private land across Canada (Canada, Environment and Climate Change 2023).

ENGOs provided bottom-up pressures for provinces. These groups directly influenced policy by working with subnational governments to provide feedback, ideas, and policy. Data revealed groups like the NCC testifying to support CEs, reinforcing that private citizens and eNGOs were clearly pursuing a specific conservation agenda. These organizations were actively facilitating discussions and providing information to create CE legislation in almost every Canadian province and territory, successfully influencing policies from coast to coast.

By actively shaping policy across Canada, eNGOs placed themselves as direct intermediaries between state-led conservation agendas and landowners motivated to conserve. These organizations were essential for the transfer of CE policies. ENGOs provided established networks for information to flow, influencing policymaking, and supporting CEs as a new instrument. One of the top groups mentioned, Ducks Unlimited, has historic ties to U.S. eNGOs, further providing avenues for transnational policy migration. As Stone (2000) notes, NGOs often work as policy entrepreneurs, with educated workers promoting policies through established, often informal, networks at subnational levels.

Policy and conservation contributions

As previously mentioned, this case study adds to the limited literature of Canadian policy diffusion. CE legislation provides a window to examine how policies migrated across subnational jurisdictions without direct federal leadership. Having a group of provincial innovators (BC, Ontario, and PEI) look to U.S. states, with eNGO pressure, is unique considering previous studies, like endangered species legislation and administrative innovation, found evidence of federal leadership (Gow 1992; Boyd and Olive 2021). Moreover, CE policy diffused without formal policy networks, successfully across political parties and within a short timeframe.

Interestingly, ideology did not appear to factor into CE policy transmission. Traditional (or hypothesized regional) political divides were nonexistent; aligning with older studies (Gow 1992) and contradicting recent ones (Wesley 2011; Lawlor and Lewis 2014). CE legislation was mostly copied and not drastically changed in jurisdictions. The only evidence of changes was from Manitoba and Quebec who, respectively, added a board to oversee disputes, and connected conservation goals to preserving Francophone culture. Policy innovation came from surprising leaders (PEI and eNGOs) and substantial U.S. influence, echoing previous findings with innovation from New Brunswick and influence migrating north to Canada (Gow 1992).

This study also expands the literature on policy transfer, especially considering most policy tracing studies aimed at “morality” policies—such as abortion rights, civil rights, and marijuana—resulting in a notable lack of study toward agriculture and environmental policies (Mallinson 2021). Such research still lacks understanding the implications of binding outside policies to unique contexts, including differences in property regimes, ecological landscapes, and social norms (Glaser et al. 2022). Additionally, the mechanisms of policy transfer are still unclear, as multiple mechanisms were likely working simultaneously, and could not be discerned from the existing data. While this research focused on providing a foundational knowledge of Canadian CE policy transfer, future work could incorporate media sources and more interviews to uncover if several mechanisms were simultaneously at work.

Using Hall's typology of policy learning, CE legislation appears to reside in second and third orders of change. Specifically, the introduction of a new policy tool (CEs) showcases the social learning and diffusive influence policymakers felt with regards to foreign jurisdictions and eNGO lobbying. This second-order change ultimately stems from a third-order transformation within subnational (and national) shifts regarding biodiversity conservation. Namely, passing CE legislation codified and legitimized the role of private land within Canadian conservation, whereas previous efforts resided in government-driven parks and publicly protected areas, CEs created opportunities for conservation within private property frameworks. Carving out a space for PLC radically transformed the scope of conservation across Canada, allowing private citizens and eNGOs to conserve landscapes where it may be politically unpalpable for governments.

One impact of having eNGOs take a central role in legislation is having unelected groups step into influential positions. This could create opportunities for governments to become negligent, necessitating questions of accountability, oversight, and impact. While these questions are outside the scope of this research, focusing on the influence and impacts of NGOs leading policy development becomes critical due to the now-hegemonic popularity of CEs in conservation on private land.

This research also provides an opportunity to understand the legislative integrity of a major PLC tool across Canada. By providing an analysis of the motivations and influence subnational governments had regarding CEs, we can place this in context with existing PLC research and future research priorities. This provides a springboard for future work to explore other aspects that could include addressing gaps like if entrenched PLC legislation is able to mitigate the increasing impacts of climate change (Fitzsimons and Mitchell 2024). Furthermore, this begins to fill a gap in understanding the importance of how social, political, and economic contexts impact CEs (Palfrey et al. 2021), especially in a country with limited scholarly focus to date (Capano et al. 2019).

This research raises a number of questions for future research. Why did CE policy traverse across ideological divides so easily? How effective and powerful are Canadian interest groups in influencing policy? Does the autonomy of subnational jurisdictions relegate the Federal government to an advisory role regarding environmental policy? Is existing PLC legislation adequately suited for the exponential growth of climate change impacts? How does the primacy of private property influence Canadian conservation policies? Given the uniqueness of Canadian policy arenas (compared to U.S. ones, for example) and my theoretical expectations being largely unconfirmed, more case studies are needed.

Conclusion

Canadian CE legislation is an uneven tapestry of enacted, amended, and vague laws which provide varying degrees of PLC, with eNGOs and the Federal government deeply invested. Policymakers drew from outside legislation to different degrees, often minimally citing other jurisdictions, and focusing primarily on eNGOs as key influencers. Most jurisdictions passed legislation from 1990 to 2000. PEI and Ontario can be considered policy innovators as both provinces were early (respectively 1988 and 1995) in codifying CEs. Excluding NFL, all provinces have legislation that either is explicitly named for CEs or has sections discussing them. There was indirect federal coercion through the EcoGifts Program, which gave landowners tax relief and recognition. Ultimately, provinces and territories took widely different approaches to debating, crafting, and defending CE legislation that bears little resemblance to other biodiversity conservation policies.

My theoretical expectations were mostly unsupported by the data. While there was evidence that policy transfer did have a temporal element, with the earlier laws of PEI and Ontario being cited by others, my second and third expectations were unclear. There were only a few instances of geographic mimicry and even these were not explicitly clear. Most geographic comparisons did not directly mimic neighbouring legislation. I expected jurisdictions would overwhelmingly rely on others when supporting of proposed legislation. While there was some evidence, with U.S. states, Ontario, and PEI being some of the most mentioned; most jurisdictions cited others to a very low frequency. Surprisingly, the most cited group was eNGOs. Ducks Unlimited, NCC, and conservation organizations broadly were the most discussed category in almost every jurisdiction. This is unusual compared to the findings from other studies of similar cases like SARA and subnational endangered species legislation (Olive 2014; Illicial & Harrison 2007).

This study provides a basis for further PLC research in Canada. It showed how invested eNGOs were in promoting CEs, and provides opportunity to analyze these laws, actors, and groups in more depth. Specifically, while I do not argue that eNGOs in this study had or have any malicious intent, the role of these large organizations that are influencing the shape and structure of PLC in Canada needs to be better understood due to the both the size of the landscapes these policies now impact as well as the ramifications that echo through CE usage.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the interview participants across Canada who agreed to be part of this research. I would also like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their comments and constructive feedback.

References

Atkins J. 2004. Conservation easements, covenants and servitudes in Canada: a legal review (Vol. 4, No. 1). North American Wetlands Conservation Council (Canada).

Berry F.S., Berry W.D. 2018. Innovation and diffusion models in policy research. Theories of the policy process, pp. 253–297.

Besco L. 2021. Carbon pricing policies and emissions from aviation: patterns of convergence and divergence. In Provincial policy laboratories: policy diffusion and transfer in Canada's Federal System. Edited by B. Boyd, A. Olive. University of Toronto Press.

Boyd B. 2017. Working together on climate change: policy transfer and convergence in four Canadian provinces. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 47(4): 546–571.

Boyd B., Olive A.eds. 2021. Provincial policy laboratories: policy diffusion and transfer in Canada's Federal System. University of Toronto Press.

Canada, Environment and Climate Change. “Canada's Conserved Areas.” Canada.ca. Available from http://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-indicators/conserved- areas.html [accessed 14 December 2021].

Canada, Environment and Climate Change. “Federal Ecogifts Program.” Canada.ca. Available from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-funding/ecological-gifts-program/overview.html [accessed 16 May 2023].

Canada, Environment and Climate Change. Government of Canada recognizing federal land and water to contribute to 30 by 30 nature conservation goals. Canada.ca. Available from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/news/2022/12/government-of-canada-recognizing-federal-land-and-water-to-contribute-to-30-by-30-nature-conservation-goals.html [accessed 12 December 2022].

Capano G.C., Toivonen T., Soutullo A., Di Minin E. 2019. The emergence of private land conservation in scientific literature: A review. Biological Conservation, 237, 191–199.

Díaz S., Settele J., Brondízio E.S., Ngo H.T., Agard J., Arneth A., et al. 2019. Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Science, 366(6471): eaax3100.

Dobbin F., Simmons B., Garrett G. 2007. The global diffusion of public policies: social construction, coercion, competition, or learning?. Annual Review of Sociology, 33(1): 449–472.

Dolowitz D.P. 2003. A policy–maker's guide to policy transfer. The Political Quarterly, 74(1), 101–108.

Fitzsimons J.A., Mitchell B.A. 2024. Research priorities for privately protected areas. Frontiers in Conservation Science, 5, 1340887.

Gerber J.D., Rissman A.R. 2012. Land-conservation strategies: the dynamic relationship between acquisition and land-use planning. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(8): 1836–1855.

Glaser M., Bertolini L., Te Brömmelstroet M., Blake O., Ellingson C. 2022. Learning through policy transfer? Reviewing a decade of scholarship for the field of transport. Transport Reviews, 42(5): 626–644.

Gow J.I. 1992. Diffusion of administrative innovations in Canadian public administrations. Administration & Society, 23(4): 430–454.

Hall P.A. 1993. Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: the case of economic policymaking in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25, 275–296.

Harrison K. 2012. Multilevel governance and American influence on Canadian climate policy. Zeitschrift für Kanada-Studien, 32(2): 45–64.

Hoberg G. 1991. Sleeping with an elephant: the American influence on Canadian environmental regulation. Journal of Public Policy, 11(1): 107–131.

Illical M., Harrison K. 2007. Protecting endangered species in the US and Canada: the role of negative lesson drawing. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 40(2): 367–394.

Kemink K.M., Adams V.M., Pressey R.L., Walker J.A. 2021. A synthesis of knowledge about motives for participation in perpetual conservation easements. Conservation Science and Practice, 3(2): e323.

Kraus D., Hebb A. 2020. Southern Canada's crisis ecoregions: identifying the most significant and threatened places for biodiversity conservation. Biodiversity and Conservation, 29(13): 3573–3590.

Lawlor A., Lewis J.P. 2014. Evolving structure of governments: portfolio adoption across the Canadian provinces from 1867–2012. Canadian Public Administration, 57(4): 589–608.

Mallinson D.J. 2021. Growth and gaps: a meta-review of policy diffusion studies in the American states. Policy & Politics, 49(3): 369–389.

Marsh D., Sharman J.C. 2009. Policy diffusion and policy transfer. Policy studies, 30(3): 269–288.

Merenlender A.M., Huntsinger L., Guthey G., Fairfax S.K. 2004. Land trusts and conservation easements: who is conserving what for whom?. Conservation Biology, 18(1): 65–76.

Ministère de l’Environnement. 2018. La conservation volontaire: vous pouvez faire la différence : principales options de conservation légales pour les propriétaires de terrains privés. Mise à jour mars 2018. Québec: Développement durable, environnement et lutte contre les changements climatiques Québec.

Olive A. 2014. Land, stewardship, and legitimacy: endangered species policy in Canada and the United States. University of Toronto Press.

Olive A. 2021. Endangered Species legislation: convergence that matters. In Provincial policy laboratories: Policy diffusion and transfer in Canada's Federal System. Edited by B. Boyd, A. Olive, University of Toronto Press.

Palfrey R., Oldekop J., Holmes G. 2021. Conservation and social outcomes of private protected areas. Conservation Biology, 35(4): 1098–1110.

Parker D.P. 2004. Land trusts and the choice to conserve land with full ownership or conservation easements. Natural Resources Journal, 483–518.

Parker D.P., Thurman W.N. 2019. Private land conservation and public policy: land trusts, land owners, and conservation easements. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 11(1): 337–354.

Pittman J. 2019. The struggle for local autonomy in biodiversity conservation governance. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 62(1): 172–188.

Ray J.C., Grimm J., Olive A. 2021. The biodiversity crisis in Canada: failures and challenges of federal and sub-national strategic and legal frameworks. Facets, 6(1): 1044–1068.

Reiter D., Parrott L., Pittman J. 2021. Species at risk habitat conservation on private land: the perspective of cattle ranchers. Biodiversity and Conservation, 30(8): 2377–2393.

Rissman A.R. 2013. Rethinking property rights: comparative analysis of conservation easements for wildlife conservation. Environmental Conservation 40(3): 222–230.

Stone D. 2000. Non-governmental policy transfer: the strategies of independent policy institutes. Governance, 13(1): 45–70.

UN I. 1992. Convention on biological diversity. Treaty Collection.

Watson J.E., Venegas-Li R., Grantham H., Dudley N., Stolton S., Rao M., et al. 2023. Priorities for protected area expansion so nations can meet their Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework commitments. Integrative Conservation, 2(3): 140–155.

Wesley Jared J. 2011. Code politics: campaigns and cultures on the Canadian prairies. UBC Press.

Wright J.B. 1993. Conservation easements: an analysis of donated development rights. Journal of the American Planning Association, 59(4): 487–493.

WWF. 2022. The 2022 Living Planet Report. Available from https://livingplanet.panda.org/ [accessed 30 June 2023].

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

FACETS

Volume 10 • 2025

Pages: 1 - 11

Editor: David Lesbarrères

History

Received: 26 January 2024

Accepted: 29 October 2024

Version of record online: 6 February 2025

Copyright

© 2025 The Author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Key Words

Sections

Subjects

Plain Language Summary

The Development and Influence of Conservation Easement Policies in Canada: A Policy Transfer Analysis

Authors

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: FH

Data curation: FH

Formal analysis: FH

Funding acquisition: FH

Investigation: FH

Methodology: FH

Project administration: FH

Resources: FH

Software: FH

Supervision: FH

Validation: FH

Visualization: FH

Writing – original draft: FH

Writing – review & editing: FH

Competing Interests

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Other Metrics

Citations

Cite As

Forrest Hisey. 2025. Provincial diffusion, national acceptance: the transfer of conservation easement policy in Canada. FACETS.

10: 1-11.

https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2024-0016

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

Cited by

1.