Introduction

For Inuit, knowledge of the environment is fundamental for a successful subsistence-based economy, but an increasingly variable climate has had an impact on society, culture, education, health, and well-being. In the Arctic, temperature has increased at twice the global rate, a process known as Arctic amplification (

Larsen et al. 2014). Indigenous Peoples in Arctic Canada, who are predominantly comprised of Inuit, are among the most directly affected by environmental change due to their integral relationship with the environment (

Harper et al. 2021;

Sawatzky et al. 2021). As climate variability can cascade across all aspects of life and culture (

Ford et al. 2010), Inuit observations of climate and perspectives of how change impacts Arctic communities are imperative for understanding environmental change at various scales (

Medeiros et al. 2017).

The observations collected by Inuit over millennia of successive activities on the land, including hunting, recreation, and travel, can contribute to knowledge that science would otherwise rely on local climate data to provide. Inuit knowledge can form the baseline of observations that can be used alongside metrological data to expand the shared understanding of climate change (

Alexander et al. 2011). Environmental observations are enshrined in the core knowledge system of

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (

IQ), defined as: “all aspects of traditional Inuit culture including values, worldview, language, social organization, knowledge, life skills, perceptions and expectations” (

Tester and Irniq 2008).

IQ is recognized as a body of knowledge gained through centuries of rigorous observation of the environment (

Watt-Cloutier 2015). The core of

IQ also represents the structure of governance, which includes laws, beliefs, and values that educate each generation that are shared by Inuit across the circumpolar world (

Karetak and Tester 2017). Integral to

IQ, as with many Indigenous worldviews, is the importance of caring for the environment; “The land is so important for us to survive and live on; that's why we treat it as part of ourselves” (Mariano Aupilaarjuk as quoted in

Evaloardjuk et al. 2004).

Inuit Knowledge can help augment gaps in data collection on climate change, while also contributing a missing and important human dimension to the scientific understanding of this phenomenon (

Riedlinger and Berkes 2001). However, the scientific imposition of defining Indigenous Knowledge is common and also applied across all Indigenous Peoples as if it were some uniform concept (

McGregor 2004).

Leduc (2007) notes that

IQ is cultivated in the mind and manifested as actions in the world. This highlights the belief that

IQ “cannot be incorporated or integrated into science because societal values are broader than traditional knowledge, which is anyway, by nature, unlike scientific knowledge” (

NTI 2005). Instead,

IQ should be acknowledged as complementary, but not interchangeable or substitutable with science. It is also important to acknowledge that Indigenous knowledge systems are not homogenous frameworks to be contrasted in a binary with science; Indigenous Knowledge is diverse and complex, incorporating relationships, motivations, assumptions, accountability, and self-reflection of the researcher (

Johnston et al. 2018). Likewise, there can be potential negative implications from the oversimplification of Indigenous ways of knowing by non-Indigenous researchers, including further harm from extractive research practices.

Colonialism has had, and continues to have, a lasting negative effect on Inuit well-being, and this history is important to understand in the context of climate change. The continuing effects of colonialism in the context of climate change are not always reflected in academic literature and colonial attitudes are still prevalent in non-Indigenous academic research spaces, especially where the direction and objectives of the research, action, and decision-making are made without meaningful engagement or input of Indigenous Peoples (

Johnson et al. 2022).

Reibold (2023) note that the capacity and capabilities of Indigenous Peoples concerning self-determination and subsequent climate change adaptation response are often ignored or undermined.

Inuit have experienced rapid and often damaging sociocultural change as they shifted from subsistence hunting and gathering to economic activities associated with trapping and trading with the arrival of the settlers and later the establishment of the Hudson Bay Company (

Tester 2017). Following World War II, Inuit were increasingly encouraged, coerced, or forced into moving to permanent settlements and giving up their seasonal nomadic way of life (

McGregor 2010). Inuit faced several other challenges, including—but not limited to—the removal of children from their families into residential schools, Project Surname

1 and the interference with Inuit naming and identity, collapse of the Arctic fox pelt trade economy, caribou population declines, outbreaks of tuberculosis and other infectious diseases, inhumane treatment of sled dogs, and abuse from Canadian settlers in positions of power (

Alia 1994;

Mancini Billson and Mancini 2007;

McGregor 2010;

Watt-Cloutier 2015;

Tester 2017). These and other challenges are important to understand because Inuit, like many Indigenous Peoples today, still experience many of the negative and lingering consequences of colonialism, including “poverty, loss of traditional culture, loss of language, loss of control over resource development, suicide, addictions, and physical and mental health disparities” (

Cameron 2012). From a health perspective, the influence of colonialism can compound the effects of climate change, which both manifest as an allostatic load in response to stress and trauma (

Berger et al. 2015).

Colonialism is compounded by the effects of capitalism and neoliberalism: capitalism drives climate change and environmental destruction through the relentless pursuit of profit over sustainability, while neoliberalism pushes for a radically free market that manifests indifference toward poverty, cultural decimation, resource depletion, and environmental destruction (

Brown 2009). Thus, there is likely a difference between the context of how climate affects Inuit communities depending on the geography of colonialism; those in urban centers with a higher degree of capitalism versus more remote communities that still substantially practice a subsistence sharing-based economy. This context is critical for the understanding of Inuit well-being today as well as how climate will affect Inuit communities in the future. We systematically review peer-reviewed literature to analyze the extent to which articles address how climate change influences Inuit society with a differentiation between urban and remote contexts. Core themes identified in the literature were compared to a participatory case study in Iqaluit, to contrast urban perspectives on climate adaptation and society. The purpose was to understand how climate change affects the well-being of Inuit, which includes social, cultural, political, and environmental effects; many of which are systemic (

Ford et al. 2010). As such, well-being was defined here based on

Kral et al. (2011), who identify well-being as the presence of family, communication, and the presence of traditional values and practices. By comparing interviews with residents and governmental workers in Iqaluit to themes identified through the systematic review, we (1) discuss how perceptions of climate adaptation and climate literacy for Inuit may differ between larger urban centers and smaller remote communities, (2) show how the effects of climate change are moderating relationships of Inuit to water and land, and (3) understand how these relationships are linked to Inuit well-being. As such, an improved understanding of the way that climate adaptation can be perceived with interconnected social, economic, and cultural realities is discussed.

Discussion

While the basis for culture, governance, and well-being fundamentally links the relationship between the environment and society, climate change challenges the practice of core values and principles of Inuit knowledge systems in Arctic communities. Through a combined systematic review of the literature and interviews with residents from Iqaluit, it was shown how perceptions of climate adaptation and climate literacy for Inuit may differ between larger urban centers and smaller remote communities. It was further outlined how participants describe the moderating effects of climate change on the relationships of Inuit to water and land and how these relationships are fundamentally linked to well-being.

For Inuit, differences in prioritization need to be examined from a culturally sensitive and knowledge-inclusive standpoint (

Vogel and Bullock 2021). In the social sciences, it has long been understood that cognitive processes, including attention, perception, and memory, are influenced and shaped by culture (

Han and Ma 2014;

Ji and Yap 2016). Therefore, some of the commonly used Western frameworks and approaches to understanding cognition may not apply cross-culturally in all the same ways (

Christopher et al. 2014). For this reason, a framework based on the four

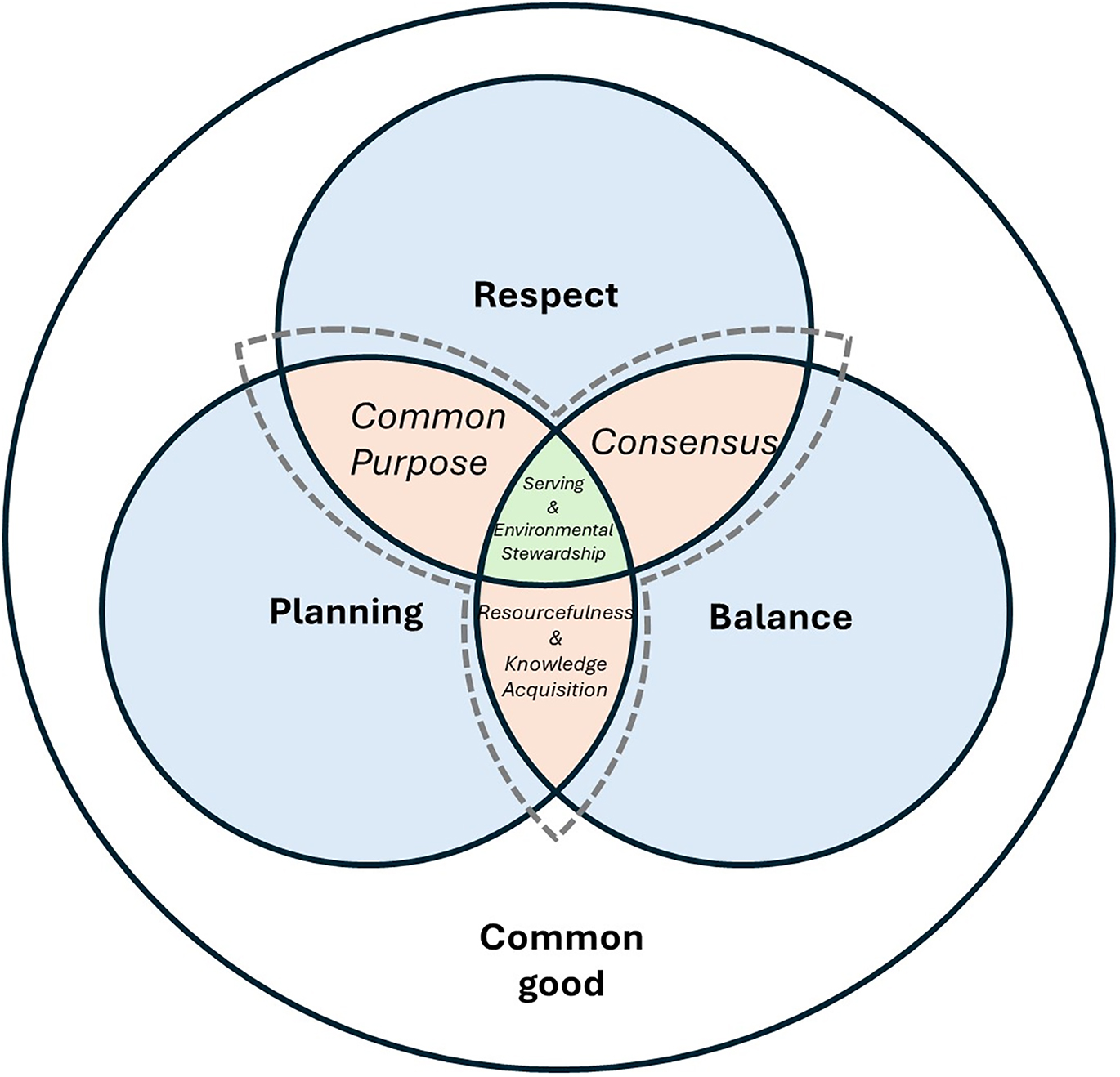

maligait (laws) and six guiding principles of

IQ (

Tagalik 2011) was used, to conceptualize and discuss Inuit perspectives on climate change, Inuit well-being, and knowledge translation (

Fig. 4).

Differences between urban and remote contexts

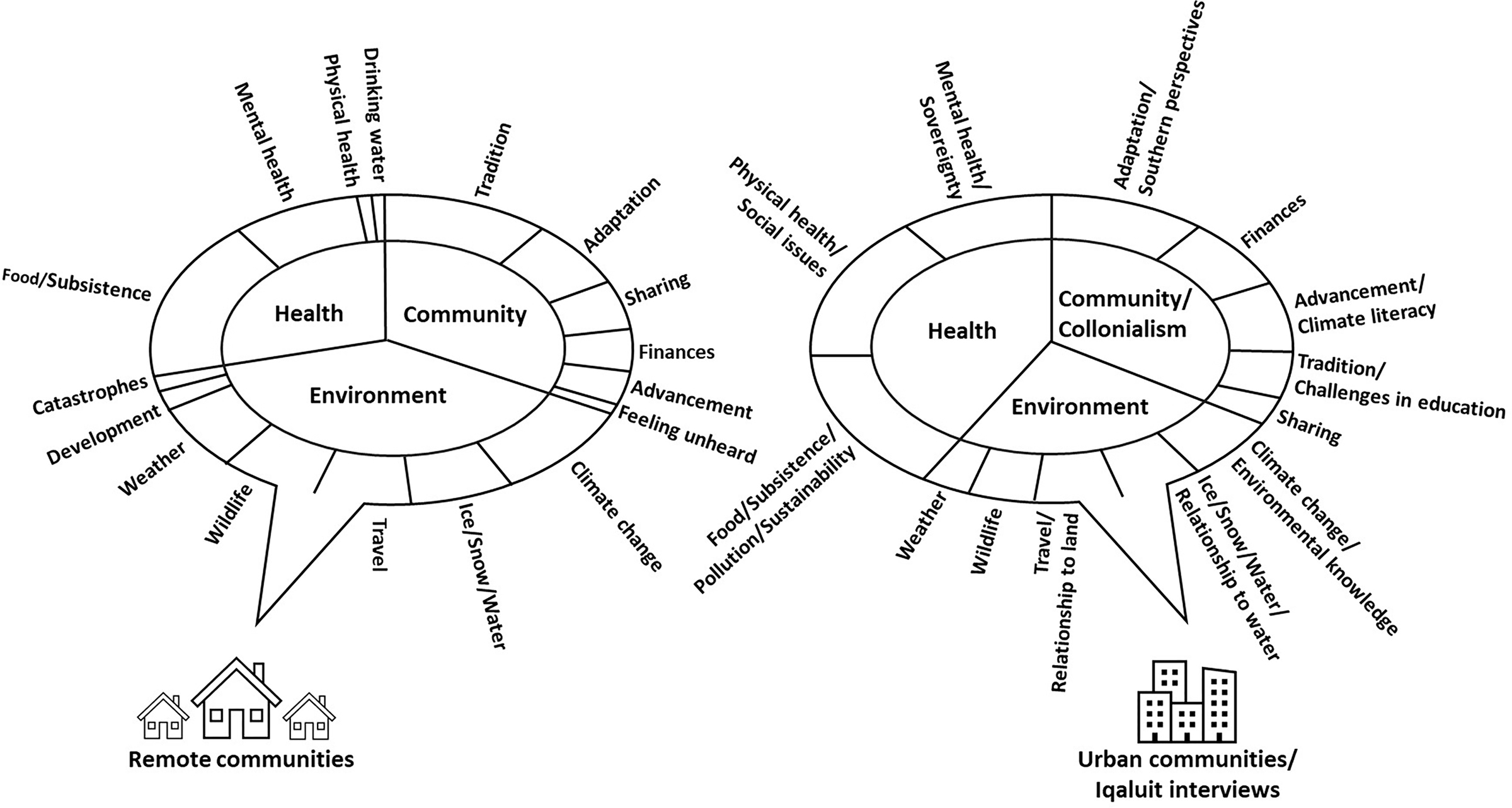

When comparing the results from the studies included in the systematic literature review to the respondents that were directly surveyed from Iqaluit, it was found that the topics discussed were largely consistent but prioritized differently. Topics discussed in the literature were summarized under the three main themes of Health, the Environment, and Community. In the transcribed interviews from Iqaluit, respondents focused on topics that were categorized as Health, the Environment, Knowledge translationand colonialism. It was found that the participants in the Iqaluit case study had much more specific mention of knowledge translation and colonialism as compared to the studies included in the systematic literature review. Several participants from Iqaluit described challenges with securing representation at higher levels in the territorial government, with Inuit often at a disadvantage in the competitive process because they do not have the required education or credentials for these positions (IR19-2, M. GN1).

The effects of colonialism were only explicitly discussed to a small extent in four of the 75 studies from the systematic review of the literature. For example,

Durkalec et al. (2015) note that participants referred to being out on the land as a necessity to escape colonial influence, as this is where they felt most closely connected to their ancestors and traditional way of life. Likewise,

Giles et al. (2013) note that some participants reject certain Western safety standards, such as lifejackets, when going out to hunt on their boats because they feel a “little bit weird” (young woman, as quoted in

Giles et al. 2013). Others mentioned a general lack of representation and regard for Inuit and

IQ in science and policy-making in the Arctic, which fosters distrust within the community towards outsiders (

Young 2021;

Gyapay et al. 2022):

“I urge scientists not to come to our communities and ask how our knowledge can be integrated into science…help us find ways to integrate your knowledge into the Inuit way of seeing the world. Help us turn the question around. This way, science can indeed be relevant to us” (Terry Audla 2014, as quoted in

Young 2021).

The vast majority of the studies in the systematic literature review address socioeconomic concerns of their participants that were not explicitly linked to the effects of colonialism.

Guo et al. (2015) note that food insecurity in Arctic communities was three times as high as the Canadian average. However, there is an imbalance within and between communities, with Inuit families more prone to suffer from food insecurities as compared to non-Inuit households. During the interviews in Iqaluit, one participant explained that “there are people whose families are going hungry because [country food] was their means of getting food for their family” (IR19-3).

Ford et al. (2013) also highlight this imbalance:

“Do we really have choices? We can't get [traditional] foods at the store, so we have to get the meat from the south. The [traditional] food at the community freezer is too expensive, so we can't access it. The food from the food bank is useful, but it's always the same thing. Sometimes we get to choose between canned vegetables and canned beans […]” (Participant, as quoted in

Ford et al. 2013).

Reduced consumption of country food is a commonly mentioned concern about health: “Anything from the land and the sea, the body needs those elements to be healthy” (Mitiarjuk Manguik, Ivujivik, 24 May 2014, as quoted in

Rapinski et al. 2018). Participants across studies in the literature review, as well as during the interviews in Iqaluit, expressed concerns about the social, economic, and housing situation within their communities (

Andrachuk and Smith 2012;

Beaumier et al. 2015;

Archer et al. 2017). As a consequence, young people leave their communities to find employment and more affordable living elsewhere (

Flint et al. 2011).

When examining the differences between literature from urban and remote contexts, as well as the responses from participant interviews in Iqaluit, it becomes apparent that most Inuit perspectives of climate change, well-being, and knowledge translation are largely linked to topics and discussions that have a negative outcome for well-being, with a few positive references (see Supplementary material). Earlier snowmelt and changes in sea ice conditions pose serious safety concerns when travelling on land and by traditional travel routes (

Archer et al. 2017;

Fawcett et al. 2018;

Lede et al. 2021). Many participants report having to travel farther distances to find country foods, which is often associated with increased financial costs;

“Ice formation every year, it's different. Some years it might be smooth to go across, some years it will be really rough. So it will take a lot longer to get to the mainland. And we have to find routes on the ocean, where we can get through the really rough ice“ (Participant from Cambridge Bay, as quoted in

Panikkar et al. 2018).

Some participants mentioned concerns about how recent changes in the environment compromise their access to clean drinking water. It was noted that “ponds have completely dried up”, which raises concerns about water security in some communities (

Harper et al. 2015). This was a concern also for interviewees from Iqaluit, who mentioned a preference for natural water sources, due to regional tap water often being “darker, sometimes with a shiny layer on top” (IR19-1), and “tast[ing] a little bit like chlorine” (IR19-2). Declines in the health of native species were mentioned, and often it seems unclear what is causing them: “Arctic char meat is white now. It's not red anymore, not sure why … most of them are smaller than back then…” (as quoted in

Galappaththi et al. 2019). The warming climate is also leading to changes in plant growth, along with new flora and fauna appearing where they had never been seen historically: dandelions, different insects, and salmon (IR19-2; IR19-3). However, it is important to note that not all responses were negative. Generally, the systematic literature review revealed that there seems to be a sense of resilience among many participants across studies:

“The way you cope with things really makes you who you are. There's always going to be change, the world ain't going to stay the same forever. There are just some things where you have no control over; […] like you have to make the best of it and adapt” (16-year-old male, as quoted in

MacDonald et al. 2015).

Relationships with the environment

Living in harmony with the land and protecting it is an important part of the traditional Inuit lifestyle, which is reflected in

Avatittinnik Kamatsiarniq, the

IQ guiding principle of environmental stewardship (

Tagalik 2011). The largest portion of the results from both the systematic literature review and interview data from Iqaluit can be considered under

Avatittinnik Kamatsiarniq. The systematic literature review suggests that topics discussed in this context were largely consistent between studies conducted in urban and remote communities. The main differences were that catastrophes and development were not mentioned in urban communities. One possible explanation could be the lack of the necessary infrastructural solutions to deal with catastrophes, such as erosion and flooding, in remote communities as compared to urban communities (

Jensen et al. 2018). Recent climatic developments suggest that Arctic communities will be faced with an increase in catastrophic weather events, including increases in (coastal) erosion, due to permafrost decay and increased impacts from flooding and harsh storms. The literature suggests that many remote communities will need to make substantial adjustments to their already existing infrastructure and find new solutions to mitigate future risks (

Warren et al. 2005). For example, Tuktoyaktuk, a small community in the Northwest Territories in Canada situated at the shore of the Arctic Ocean, has experienced severe coastal erosion from increased storm surges since the 1930s (

Johnson et al. 2003). Residents are concerned and fear the possibility of having to relocate: “Erosion of the shoreline has been happening for a while now. We are noticing it more and more as it gets warmer and warmer” (Maureen Gruben, Tuktoyaktuk resident, as quoted in

Andrachuk and Smith 2012). With the help of ongoing scientific monitoring of shoreline erosion, the community has since been working on developing suitable strategies to adapt their local infrastructure to mitigate further impacts on the settlement (

Johnson et al. 2003).

Living in the Arctic requires certain levels of creativity and innovation to survive with limited access to resources (

Tagalik 2011). There was a strong consensus between urban and remote communities about

Qanuqtuurunnarniq, the

IQ guiding principle of resourcefulness. Climate change is having diverse and cumulative effects on the way that Inuit spend time on the land, affecting the timing for hunting, fishing, and harvesting, and making it more dangerous to travel on the land (

Weatherhead et al. 2010): “Right now, when you travel, even if you are a good hunter, it is dangerous. [The ice] looks like it is all the same, but underneath it is not” (E. Ishulutaq 2013, as quoted in

Rathwell 2020). These safety concerns were also addressed by the interviewees from Iqaluit. As a result, Inuit “have to be extra careful or [do not] go [out on the land] at all” (IR19-5). Adaptation strategies to these dangers are similar in both types of communities. For example, the use of modern technology, such as the Smart Ice application (

Bell et al. 2014;

Reed et al. 2024), and weather forecasts to help with navigating challenges and emergency response out on the land are common.

Beaulieu et al. (2023) showcase how Inuit researchers and non-Inuit partners can mentor youth and empower communities to use their own language, experience, and knowledge, to improve safety and the monitoring of the environment. Elders often reflect on how education and technology can help mobilize Traditional Knowledge across generations: “Now we need young people to teach us” (Elder as quoted in

Galappaththi et al. 2019).

Our systematic review of the literature identified numerous studies that focused on climate change, with mention of the earlier snowmelt, changes in sea ice, vegetation, and warmer weather (

Laidre et al. 2018;

Lede et al. 2021); however, not all participants within these studies identified that the recent changes in the environment are associated with climate change. Some participants expressed the belief that “things will get back to normal next year” (

Ford et al. 2009). Indeed, during the interviews with participants in Iqaluit, several expressed that climate change was an imposed Western concept, noting that climate has always been in flux (IR19-1).

Health and well-being

There was a difference in prioritization between topics in the literature, where urban interviewees predominantly mentioned topics about health and well-being, while remote interviewees focused mostly on concerns about the state of the environment. Similarly, when prompted to discuss issues related to water and land, participants interviewed in Iqaluit often diverted the discussion toward economic and social issues related to past and ongoing effects of colonialism. For Inuit living in an urban community, this suggests that health and social concerns were more prominent than concerns regarding the environment and climate change. However, it is also important to note that Inuit living in urban centers likely also feel the everyday influences of colonialism to a higher degree than those in remote communities (

Laruelle 2019). Participants from Iqaluit identified social issues as the biggest obstacle for Inuit in their day-to-day lives, affecting physical and mental health and disrupting relationships with the land. The rapid shift from a subsistence lifestyle to the wage economy, especially seen through the lens of colonialism, has been dislocating physically, emotionally, and spiritually: “Honestly, in a place that has so many other social issues, and issues within systemic issues and things like that, a lot of people just can't afford to pay attention to [climate change] right now” (IR19-3). This was a sentiment that was also reflected in the literature; while many participants stressed the urgency of addressing climate change, one participant in a study by

Prno et al. (2011) mentioned that while climate change is a concern, their ““community has [social] issues [that they] need to deal with first”’. As such, it becomes apparent that climate change cannot be viewed in isolation from socioeconomic impacts, as there are intersecting issues that combined manifest as an allostatic load that can affect well-being, including pollution, sustainability, social issues, and sovereignty (

Berger et al. 2015).

Concerns about the loss of traditional practices and

IQ in relation to climate change were commonly mentioned in both the systematic literature review as well as by participants from the case study in Iqaluit. The loss of a connection to traditional lifestyle was referred to as having a strong implication for Inuit mental health and well-being (

Flint et al. 2011;

Durkalec et al. 2015;

Bishop et al. 2022). Knowledge is traditionally passed on from generation to generation; however, recently there are fewer opportunities for youth to engage in traditional practices and learn from their Elders:

“Back then, more young people were trained to be hunters and providers. But not anymore. That knowledge isn't passed on. Because there's less incentive. [Young people] can eat store bought food, they also have school. They are preoccupied“ (Anonymous 2015, as quoted in

Archer et al. 2017).

There are some differences between urban and remote communities, as to which sub-themes were addressed. In remote communities, challenges in education and climate literacy were not mentioned. One possible explanation for this difference could be the decreasing practice of intergenerational education between Elders and youth in urban communities, as compared to remote communities where the Traditional Knowledge transfer is still somewhat intact (

Herrmann 2016).

Simonee (2021), who is an Inuit researcher, notes that Inuit “often feel stuck in the middle between Traditional Knowledge and modern services, trying to determine what information is most reliable […].” As weather and wind patterns continue to change, Indigenous Knowledge will get less reliable for navigating on the land (

Archer et al. 2017).

A vital component of Inuit culture is the inherent care for others and maintaining strong relationships between members of a community (

Tagalik 2011).

Pijitsirniq, the

IQ guiding principle of serving, was largely consistent in how it was addressed in responses from both remote and urban communities. Increasing structural change and shifts towards a wage economy have replaced the sharing culture for the most part (

Goldhar and Ford 2010;

Gilbert et al. 2021): “I don't like selling [the traditional foods] for money, but how else can I afford to hunt?” (Male hunter, middle-aged, as quoted in

Ford and Beaumier 2011). Many participants expressed their frustration and sense of helplessness: “There's nothing you can do” (Youth, as quoted in

MacDonald et al. 2013). A subsistence-sharing culture is only one of the many traditional practices that are gradually being lost or replaced by adopting a more Western way of life (

Archer et al. 2017).

Conclusion

An increasingly variable climate challenges the subsistence-based sharing economy of Inuit, which can negatively affect their well-being. To get a better understanding of how climate change affects the Inuit relationship with the land, their well-being, and whether these experiences differ between urban and remote communities, published literature on interview studies with Inuit across the North American Arctic was examined and compared with an interview study with residents conducted in Iqaluit. This approach, which considers IQ values within the analysis, reveals that there are some positive outcomes for Inuit well-being in the context of climate change, such as building resilience, developing adaptation strategies, and revival of traditional practices for a more well-balanced lifestyle. However, climate change is predominantly affecting Inuit relationships to water and land in a negative way, and this is exacerbated by differences between Inuit and Western understandings of climate and environment. Results have been largely consistent across urban and remote communities, with differences in the prioritization of certain topics in the context of climate change. A greater need to listen to and understand Inuit perspectives to respect the knowledge that they hold, to include observations of how climate change is affecting the Arctic, and to implement their knowledge in decision-making and funding acquisition in Arctic research, was identified. Inuit well-being should be of primary concern not only for Inuit, but also for the non-Inuit who live, work, and conduct research in the Arctic. More effort needs to be put into developing a complementary knowledge system for science and IQ, with care to not value either above the other.