Introduction

To better understand the context of climate change in the Arctic, it is important to widen the perspective on how knowledge generated should subsequently be communicated. Insights from knowledge mobilization can have far-reaching implications on national and international policymaking (

Flynn and Ford 2020). Yet, the communication of climate change remains an inherently difficult task, due to the scope, complexity, and variability of change. Uncertainty has introduced controversy and skepticism among some elements of society (

Ballantyne 2016). Many causal links between the changes seen and experienced are yet to be understood, which is even more apparent when discussing Arctic systems. As such, the contextualization and communication of climate change research often requires a definition of what the message will be to effectively communicate it.

Technical language is difficult to absorb and appreciate, and researchers often have a difficult time summarizing results in a way that is non-technical, yet at the same time preserves core findings (

McBean and Hengeveld 2000). Intrinsically, communication about climate change requires careful thought into the purpose of the message, how it should be framed, who should frame it, and which mode or channel of communication is most appropriate (

Moser 2016). There are many different conceptualizations and synonyms for communicating research in the literature, which differ slightly based on discipline.

Burns et al. (2003) define science communication as “the use of appropriate skills, media, activities, and dialogue” (p. 191). This definition emphasizes that science communication should produce awareness, effective responses, interest, opinions, and understanding of the information communicated, which focuses on the intention for intervention and application as a principal mechanism for communication (

Burns et al. 2003). Similarly, the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (

SSHRC 2021) defines knowledge mobilization as “the reciprocal and complementary flow and uptake of research knowledge between researchers, knowledge brokers, and knowledge users—both within and beyond academia”. In practice, this implies that a two-way transfer of knowledge, the demonstration of reciprocal and complementary flow, should inform research priorities, theories, and methodologies within academia. Outside of academia the ability to engage and communicate reciprocally should inform public debates and policymaking, as well as lead to informed decision-making by businesses, governments, the global media, and civilians (

SSHRC 2021).

In a diverse society, effective communication and informed decision-making require the representation of all parties involved. For the Arctic, knowledge of the environment has been the foundation of the culture, heritage, and governance of Inuit for generations; yet, anthropogenic climate change has challenged multiple scales of the interconnectedness between the environment and society (

Durkalec et al. 2015). Maintaining harmony and continually planning and preparing for the future are core cultural beliefs of Inuit (

Tagalik 2012); however, an increasingly variable climate has directly challenged these concepts within a person’s lifetime (

Watt-Cloutier 2015). Traditional provisioning related to the subsistence-sharing economy for Inuit practiced over generations has very recently been disrupted by unpredictable weather related to climate variability (

Wenzel 2009;

Pearce et al. 2015).

The need for more research on how climate change influences the Arctic and its Peoples is clear, but effective communication of the knowledge generated from these studies to communities is equally as important (

Barber et al. 2008;

Moser 2016). To ensure effective communication, researchers are encouraged to draft a communication plan in the early stages of their research, and if applicable, appoint a member of the research team with the task of overseeing the implementation of this plan. By using plain language and keeping it relevant to the community, researchers can avoid community distrust and encourage meaningful discourse with community members (

ARI 2013). The importance of such discourse is reflected in the Indigenous concept of

Etuaptmumk (two-eyed seeing), which was initially introduced by Mi'kmaw Elders Albert and Murdena Marshall of the Eskasoni First Nation to make scientific approaches more knowledge-inclusive (

Bartlett et al. 2012). It emphasizes that a combination of Western scientific knowledge paradigms, Indigenous knowledge systems, and collaboration between scientists and Indigenous Peoples in research is key to a more holistic understanding and meaningful communication (

Wright et al. 2019). While reciprocal communication and engagement with Indigenous Peoples are now recognized as a principal basis for decision-making in Canada, researchers often do not know how to initiate these conversations before, during, and after their projects (

Bowie 2013;

Henri et al. 2020). When the community’s and researcher’s needs and interests converge, it can lead to a highly productive collaborative partnership, through which knowledge can be co-produced in a way that benefits all parties involved.

Wolfe et al. (2011) reflect on such a scenario, where an International Polar Year (IPY) project in Old Crow in the Yukon, was developed in close partnership over several years to further the understanding of the impact of climate change on the environment and society. However, many researchers continue to struggle with meaningful community involvement and communication, even if they have the right intention from the onset. This is partially due to discussions and disagreements about research agency, research impact, and appropriate methodologies which continue to get in the way of a two-way transfer of knowledge and collaboration between researchers and Indigenous communities (

Gearheard and Shirley 2007).

While these challenges are not limited to any particular group of researchers, they add an additional layer of complexity for early career researchers (ECRs). There is currently no universal clear-cut definition for ECRs. In practice, ECRs are often defined based on their age, career duration, or academic experience (

Frandsen and Nicolaisen 2024). Here, ECRs are defined by university students (bachelor, master, and doctoral candidates) and post-doctoral researchers (

Bohleber et al. 2020). In other words, this study refers to researchers who are contracted for a short period, typically ranging from 2 to 4 years depending on program requirements. As such, given that community-based approaches to research take time, ECRs can often struggle with the allotted time window associated with their undergraduate or graduate programs. While budgetary obstacles are always an issue, the lack of time to gain the amount of experience necessary to conduct meaningful engagement with Indigenous Peoples is a primary challenge, especially for ECRs (

Tondu et al. 2014). Likewise, meaningful knowledge mobilization requires an enhanced understanding of local contexts, followed by clear guidelines on how engagement should occur and how communication can be improved on the individual research scale—which in practice takes years of experience and collaboration to develop.

Ford and Flynn (2020) suggest that there is no one success formula for knowledge mobilization, but rather a general guideline that needs to be adapted into specific cultural contexts within the North American Arctic. Three key principles are suggested for effective knowledge mobilization: respect, mutual understanding, and researcher responsibility (

Ford and Flynn 2020). In practice, however, this implementation remains challenging, especially within the natural sciences, where researchers receive very little training on community-based research (

Gearheard and Shirley 2007). Additionally, while these guidelines are addressing knowledge mobilization for researchers more broadly, there currently remains limited guidance on how to overcome some of these logistical challenges outlined above, specifically directed at ECRs who may face additional obstacles due to limited experience and access to resources (

Tondu et al. 2014;

Flynn and Ford 2020).

Here, we establish how experienced practitioners of knowledge mobilization in the Arctic recommend ECRs to approach communication of climate change-related research in the Canadian Arctic. By drawing on the perspectives of experienced practitioners, we (1) outline common challenges and barriers for ECRs to conduct and communicate their research in a way that is meaningful to the target audience, (2) provide informed guidelines as starting points for ECRs to engage in more meaningful science communication despite common challenges, and (3) highlight knowledge gaps for future work to advance the current understanding and guidelines on how climate change research should be communicated in practice. Through these reflections on challenges and recommendations outlined by practitioners, the goal was to contribute to the ongoing discussion about how to make science communication more community-focused, while also encouraging researchers to think about their role in the purposeful mobilization of knowledge early on in their research process.

Results

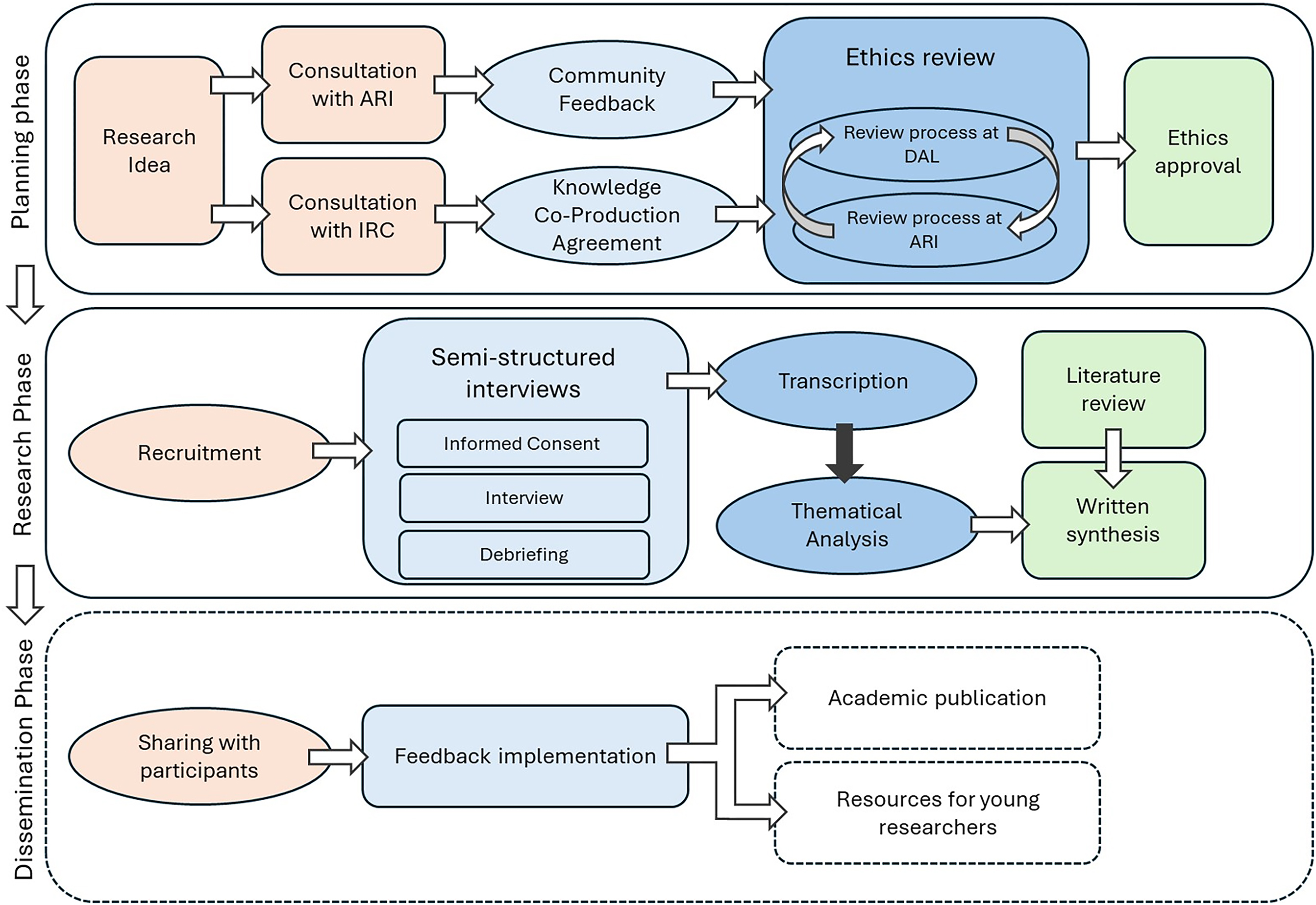

The goal of this research was to scope out common challenges with community engagement and meaningful knowledge mobilization in the Canadian Arctic faced by ECRs, address those challenges by providing generally applicable guidelines to overcome these challenges, and identify important knowledge gaps for future research. As such, interview participants were selected for their professional experience with community engagement and knowledge mobilization of research in the Canadian Arctic. A total of six practitioners from the Northwest Territories and Nunavut were interviewed (

Table 2). Half of the participants indicated that they grew up in the Canadian Arctic, while the other half indicated that they moved to the Arctic for work at a later stage in life. Five of the participants interviewed identified that they were currently in a profession that is directly involved with knowledge mobilization of climate change research, while one indicated to have worked in this capacity in a previous role. The following sections outline the challenges and recommendations based on the content analysis of these six expert interviews.

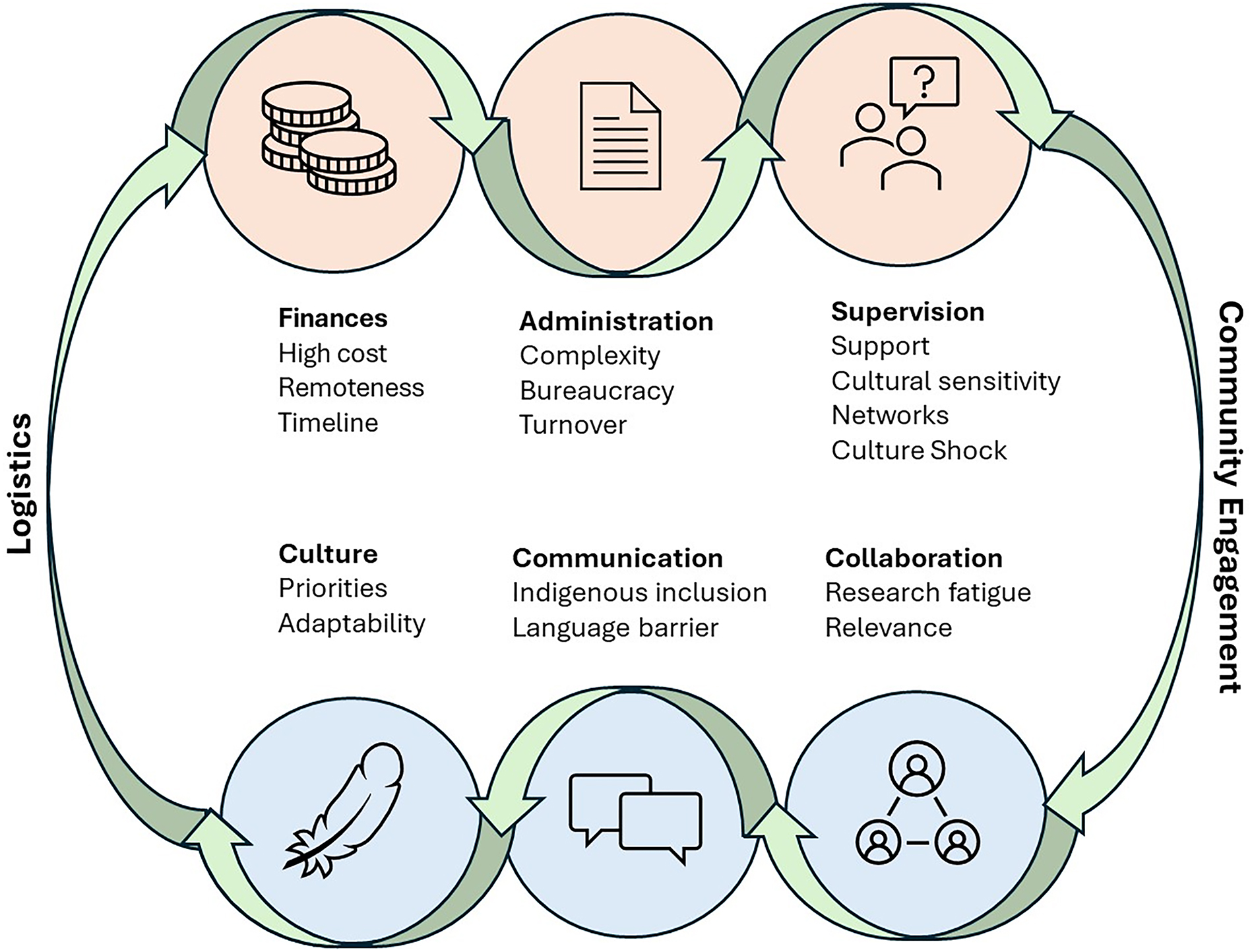

All participants mentioned that they, or their organization, are frequently consulted by external researchers on how to communicate their research back to Arctic communities in a meaningful way—and all six participants agreed that there is a need for better and more purposeful communication of knowledge in climate change research. Participants mentioned different means by which they work together with communities to obtain feedback and guidance on how to conduct knowledge mobilization in a more dedicated way, including community visits, consultations with community leaders, workshops, presentations, youth outreach projects, teleconferences, and surveys (P2; P3; P4; P5). When asked about the challenges they see for ECRs, participants voiced many from a logistical standpoint, as well as from a community engagement perspective (

Fig. 2). To overcome some of those challenges, participants offered some recommendations on how to conduct research in a way that allows for a more meaningful knowledge exchange (

Fig. 3).

Challenges

During the interviews, participants identified many challenges that ECRs are faced with on their path to conducting and communicating their research in a meaningful way, which can be largely classified into logistical and cultural obstacles. All participants acknowledged the discrepancy between the high cost of research in the Arctic and the funding made available. Hosting in-person workshops or events to seek feedback from the community before the research project, as well as communicating research results back to the community, is therefore not always feasible. Many Arctic communities are very remote, and infrastructure is sparse, which makes community visits even more difficult (P1; P4). However, upfront in-person visits are fundamental in establishing close relationships with local partners and learning more about local research priorities, which is essential to shaping research designs and methodologies before the start of each project (P3; P5; P6). Participants highlighted the fact that community work takes a lot of time and local presence to build connections and trust, a process that often extends way beyond the timeline that a Master’s or Ph.D. project would allow for (P3; P4; P5). While diligent research takes time, life in the community continues, priorities shift, and results and outputs can fall behind (P5). Besides creating obstacles to knowledge mobilization, a lack of funding and limited time can also create other problems, such as a heightened willingness to take risks during bad weather conditions that can put both researchers and local research assistants at risk (P4);

“Occasionally we hear about researchers being a bit pushy, (…) they have their narrow time windows where they scheduled to be in the north, and they get there and maybe the weather is too dangerous to be going out to the site because that happens” (P4).

While licensing processes, ethics reviews, and community engagement are broadly known to be important, they also take time (P1). Between the high workload of staff and the fast turnover of employees in the Arctic, messages can get lost and non-responses can be high. This adds a layer of complexity where it is hard to keep track of the professionals to contact with questions concerning communication of knowledge (P2; P5; P6). Therefore, having well-connected networks is very important, but often ECRs do not have the time to establish these relationships upfront, which limits the availability of local support (P2; P3). Participants note that most academic researchers come from a Western context and would benefit from more guidance on how to conduct their research in a more culturally sensitive manner (P2). Cultural sensitivity is particularly important when it comes to communicating controversial research results to communities and the public, and it requires a lot of informed reading and immersion in the culture and history of the communities to avoid causing harm (P4; P6);

“I've seen that a lot with researchers where they're like, “Oh my God, I got this data on this new parasite that's coming to affecting the health of beluga whales. It can totally affect human health. I better tell somebody about that”. And they do it in very irresponsible manner, without any other contextualizing of the information - and so huge fear comes in, people stop eating. We have people in the Kivalliq region who do not eat beluga whale to this day because of a message that was given 40-50 years ago about mercury levels in beluga whale” (P6).

With the large volume of research projects, due to the increased interest in climate change impacts, participants said it is also crucial to make sure that the new research is relevant to the communities, to avoid generating research fatigue (P4; P5). If communities are overwhelmed with the sheer amount of research being conducted, research fatigue can constitute a barrier to community engagement in research and knowledge communication, as one participant highlighted (P5).

“I've heard this, that Inuit are one of the most studied people on Earth, and there is quite a lot of research fatigue that occurs. So, it's not really that we want more researchers, is that we want more quality researchers” (P4).

The history of research fatigue means that much more diligence is required to review baseline research on the topic before engagement with communities, such that feelings of repetition do not occur for subsequent projects on the same topic (P5). At the same time, ECRs should remain humble, recognize and accept when proposed projects are decided to not be moved forward (P4). Communication and engagement are also impeded by differences in language. Seldom are ECRs well-versed in the local dialects, or have the funds to hire a local translator, which further limits the scope of their outreach (P1; P5; P6).

Meaningful involvement of Indigenous Knowledge and skillsets within the principal research itself, let alone communication of results, is often challenging according to participants. Several participants noted that even with the creation of best practices to decolonize the research process, there remains a challenge to establish how effectively these policies are implemented on a small scale (P2; P5). For example, P5 noted that it is common place for research teams to contact a local outfitter for assistance in bear monitoring, but questions the applicability of this in terms of meaningful engagement:

“There's a lot of ways that researchers can claim that they are incorporating local knowledge or involving community members that are really perfunctory or not meaningful, but it's again so hard to really do a qualitative audit on all of these hundreds of projects to determine “OK, which are legitimately meaningfully incorporating new knowledge and building capacity and using that knowledge to inform our research approach?”. It's difficult” (P5).

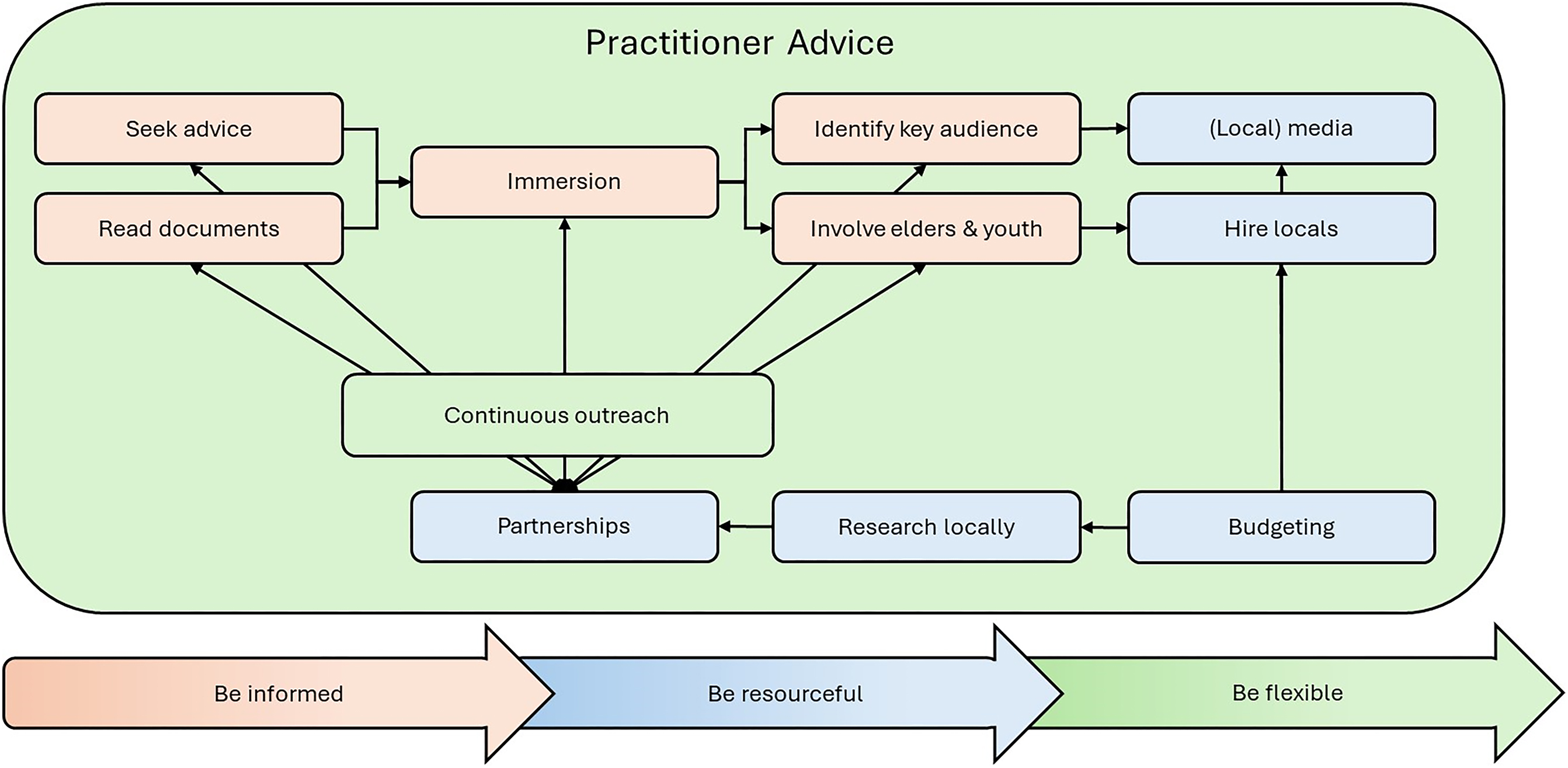

Recommendations

Participants were asked how they would advise ECRs to communicate the knowledge produced by the work that they do. The recommendations that were given by the participants of this study can be summarized broadly as approaching research in a well-informed, resourceful, and flexible manner (

Fig. 3).

Participants broadly suggested that researchers seek advice from communities at an early stage, ideally before the research project has started (P1; P2; P3; P5; P6). The highlighted benefit is to establish a grounded support network from an early point, which can be helpful both in shaping the research project to make it community-relevant and making a feasible project-tailored dissemination plan of how the research will be communicated to the community (P3; P5; P6). The best way of doing this well is through direct partnerships (P3; P4; P5; P6). Here, it can be helpful to have a supervisor who is well-connected with the communities of interest, to help establish these partnerships and make those connections on behalf of the student, to save time and resources (P3). Local partnerships are mutually beneficial in that they can provide important contacts, help you to identify your target audience, or help find effective modes of communication, such as connecting you with local schools or local media sources; but they can also make sure that your research is in line with local research priorities (P1; P2). Participants mentioned popular means of knowledge mobilizing in their communities, or communities they work with, are the use of local radio, hanging posters in the regional post office, organizing open houses, posting events and connecting on Facebook (P1; P2; P3; P5; P6). Proceeding, as well as alongside seeking advice, the ECRs should be doing a lot of background research, both on what has already been done on that specific research topic, as well as on the history and culture of the target community, as this will be a necessary step towards more culturally sensitive conduct, both concerning the research process itself and knowledge mobilization (P4; P5; P6);

“There are a number of stories, and I guess historical context, that researchers should be aware of coming working with Inuit, and I would advise that you become familiar with Inuit history, Inuit political history, and that sort of thing before coming up. That would help you recognize the sensitivities around certain subjects and that would go a long way toward not souring any relationships that you're trying to develop” (P4).

As P1 summarized, ultimately, the best approach is to “come up North and find out”. While spending time in Arctic communities is costly, setting a few extra days aside to attend community events has been noted to have an enormous value in building trust, as well as getting a sense of the community (P4). Participants pointed out that when thinking about knowledge communication, researchers must ask themselves what they are trying to achieve with the information that they are communicating, for example, whether the communication is directed at awareness or action (P5; P6). Likewise, research that focuses on passing information from Elders to youth is especially appreciated;

“We often like to involve youth in activities because that develops their skill set and it (…) makes for us to have a strong future workforce - not really the way I want to describe it - a strong future generation of adults. If they're able to have these opportunities for children, so any sort of research that incorporates that type of skill development in youth usually is a lot more favourable within a community” (P4).

With limited funding availabilities, ECRs often must be creative (P4; P6). For example, having a strong connection with local partners can be helpful to communicate research locally and avoid costly travel (P4). Being based in a “community hub city” (P4), where travel to the Arctic is more accessible due to the established infrastructure, can also further reduce some of the costs associated with communicating knowledge. However, most participants agreed that it is important for knowledge mobilization to be treated as a continuous process and occur throughout the project, and not be left until the end (P1; P3; P6).

Knowledge gaps

Discussions about the need for meaningful and effective knowledge mobilization are ongoing across all the Arctic organizations that were contacted for this study. The acknowledgment of vague protocols and guidelines was made during the conversations with participants. Participants noted that sometimes initiating communication with the community can be “as easy as” putting up a poster at the regional post office or making an announcement through the local radio or Facebook (P1; P2; P6). However, it is also important to establish and nourish strong relationships, based on mutual goals and interests for meaningful conversations to work well:

“You need both the buy-in from the researcher, and you need the buy-in from the regional organization, and you need the buy-in from the community to do [research] successfully - without that, without any of those things going, it’s not going to work” (P6).

As such, there remains a need to further the discussions on how to conduct and communicate research in a way that meets community needs, which may be different across communities. Here it is important to emphasize that to be able to develop more effective protocols and guidelines, research must be co-led and co-produced with equal power dynamics between researchers and Indigenous institutions:

“You already know what the project is, what the goals of the project are, and at that point in time if you’re asking community members, your thoughts – it’s not true collaboration, it is more extractive than anything else” (P3).

There will likely never be a “one-fits-all” answer for how to conduct effective communication and engagement, and it is highly dependent on the nature of the research, the community involved, and the partnerships and trust built between the researcher and the community (

Wolfe et al. 2007;

Pearce et al. 2009;

Flynn and Ford 2020; P3). However, researchers, communities, and organizations will need to continue this conversation together, to expand mutual understanding, when it comes to communicating research;

“There’s no silver bullet to communication and it’s all about understanding the needs of that community at that time, at that place and those people, and also regionally, and nationally, and internationally as well. So, to be open and to be kind of adaptable to the changes of communication are just as important as being adaptable and open to your research that you’re doing as well” (P6).