Framework and proposed indicators for the comprehensive evaluation of inclusiveness: the case of climate change adaptation

Abstract

Inclusion has been gaining increased attention in various domains, including education and the workplace, as well as development, governance, urbanization, and innovation. However, in the context of climate change adaptation (CCA), the concept of “inclusiveness” remains comparatively underexplored, with no overarching framework available. This gap is crucial, given the global scope and multifaceted nature of climate change, which demands a comprehensive and inclusive approach. In this article, we address this deficiency by developing a comprehensive conceptualization of inclusive climate change adaptation (ICCA). Grounded in ethical analysis, our framework is presented for discussion and practical testing. We identify nine specific priority areas and propose one to two qualitative indicators for each, resulting in a suite of 15 indicators for the evaluation of ICCA policies. This research not only highlights the urgency of incorporating inclusiveness into CCA, but it also provides a practical framework by which to guide policymakers, practitioners, and researchers in this critical endeavor. By acknowledging and accommodating diverse value systems and considering the entire policy process, from conception to evaluation, we aim to foster a more inclusive and sustainable approach to CCA.

Introduction

Promoting inclusion has been an on-going concern in several contexts, including development and growth, decision-making and governance, cities and urbanization, innovation, and education and the workplace. The conceptualization of inclusion and what it constitutes is surprisingly diverse, and no overarching framework exists for evaluating the degree of inclusiveness in broad or diverse contexts. Without such an overarching perspective, there is a risk of omission of contexts where inclusion matters. The risk of omission also applies to the implementation and evaluation phases. References are commonly made to equity, discrimination, justice, diversity, and inclusion (UN Womenwatch 2009; Grant 2019; Norton 2019; Berry and Schnitter 2022; Environment and Climate Change Canada 2022; Wing et al. 2022), but the translation of these concepts into practical evaluation tools still requires development.

We have selected the example of climate change adaptation (CCA) because it provides a very broad context for both human and non-human situations. CCA is defined as the process of adjusting to an actual or expected climate and its effects on natural or human systems (IPCC 2022a). Scholars have long criticized the inequitable participation in CCA planning and implementation that has undermined equitable vulnerability reduction because of the failure to overcome entrenched power relations and ensure the meaningful inclusion of the most marginalized (Hügel and Davies 2020; Eriksen et al. 2021). A number of scholars have recently argued for a more inclusive approach to stakeholder engagement in CCA (Chu and Cannon 2021; IPCC 2022b; Martin et al. 2022; Singh et al. 2022). Martin and colleagues (2022) ranked inclusion as one of ten new insights in climate science 2022, whereas Singh and colleagues (2022) argue that inclusion should be a key principle by which to evaluate the success and effectiveness of CCA.

A recent systematic review of inclusive climate change adaptation (ICCA) revealed a growing interest in the idea of “inclusiveness” in the climate change context (Pham and Saner 2021). The concept of ICCA, however, has neither been fully developed nor used in formal evaluations of public policies or practices. There are also no checklists or indicators for systematically evaluating the inclusiveness of a policy or action plan in the CCA context.

An attempt was recently made to apply the principles of equity, diversity, and inclusion to the CCA context (Hoicka et al. 2022; Tangirala 2022), but the lens of inclusion was limited to a managerial tool. We must stress that the Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) approach used in human resources is insufficient to serve as a model. Other contexts where diversity matters need to be included, such as politics and governance or even the welfare of non-human sentient beings. Moreover, the practice of EDI often tends to be too narrow in application. For example, EDI may be focused only on the moment of hiring staff. Thus, using a logic model, we will evaluate inclusion across the entire process—from planning to evaluation.

The conceptualization of ICCA should be grounded in moral reasoning. All decisions are built on values, which are entwined in the entire decision-making cycle, from the identification of priorities in the planning process through standards setting and implementation, and finally to performance evaluation. The use of an ethical lens opens the door to conceptual and analytical tools in specialized fields such as environmental ethics, business and workplace ethics, and political ethics (Light and Rolsten 2003; Zgheib 2014; London 2021). For example, environmental ethics provides convincing arguments for the broadening of the moral circle from the traditional human focus (“anthropocentrism”) to the inclusion of sentient animals, other life forms, biodiversity, and even habitats (“non-anthropocentric ethics”) (Singer 1981). Finally, ethical considerations are especially relevant in the case of CCA, which is an exemplar of climate justice theory and practice (Robinson 2018; UN 2019).

The ethical analysis in this paper provides a broad conceptual foundation for ICCA indicators. Our conceptual approach also includes all key steps in policymaking, namely initial planning, implementation, and evaluation. Within the framework constructed this way, we then identify nine priority areas and corresponding performance indicators. We believe that this type of tool is required in climate change contexts. Our tools are applicable to several contexts, either to evaluate existing concepts of inclusion or to develop inclusion policies in new contexts. Casting the conceptual scope widely enables us to establish a conceptual basis that will bring us closer to achieving the ambition of thinking inclusively about inclusiveness. The resulting heuristic tools are applicable to contexts outside of ICCA, where the idea of inclusiveness is also gaining importance.

Methods

In this paper, we develop an argument for how inclusion, inclusiveness, or inclusivity (we use these words interchangeably) should be conceptualized, implemented, and assessed in the context of CCA and propose a set of indicators that are testable in practice.

First, we use a comparative approach to examine a broad set of related contexts. Here, the focus is on inclusiveness “in practice”, meaning how inclusiveness has been conceived, implemented, and assessed in different contexts, sectors, and locations. We therefore compared international frameworks that have been globally accepted and applied to achieve inclusiveness in development and growth, decision-making and governance, cities and urbanization, innovation, and education and the workplace. We focused on (i) frameworks that were initiated by an international organization and applied in different countries and (ii) frameworks that included performance. The input from these comparisons provides insights regarding inclusiveness evaluation in diverse contexts and can serve as a foundation for developing our framework for ICCA.

Second, we carry out a broad ethical analysis that draws upon the pluralistic values of climate change ethics, emphasizing global justice, intergenerational justice, ecological justice, and business ethics. We highlight diversity, equity, and inclusion in contemporary organizations as well as political ethics, ensuring cooperation, transparency, and accountability in governance and policymaking. While climate change ethics, with its focus on the concept of climate justice, provides rich resources for the moral reasoning of inclusiveness, we believe that business ethics and political ethics offer valuable insights concerning the practical implementation of a more inclusive approach to CCA.

Lastly, we employ a standard logic model in a systematic and visual way to describe the relationships among the resources of the operation of the program, the activities planned, and the changes or results that the program is expected to achieve (W.K. Kellogg Foundation 2004; Frechtling 2015). Once a program has been described in terms of how it works and to what end, this logic model can be used as part of an evaluation study as it provides the foundation for looking at implementation and outcomes, as well as defining boundaries and identifying critical measures of performance (Pringle 2011; Marino-Saum 2020). In our study, the logic model serves as a conceptual framework by which to facilitate the selection of indicators and identify the most relevant indicators for a specific domain, problem, and location. This will, in turn, yield an indicator set that is at once transparent, efficient, and powerful in its ability to assess the state of any program or project without losing sight of the overall climate change context.

Based on this argument, we identify a set of 15 plausible indicators, which serves as our hypothesis. We will personally attempt to “falsify” this set of indicators in working with practitioners and invite the academic and practitioner communities to do the same.

Inclusiveness in related contexts

To better understand the conceptualization and assessment of inclusiveness, we reviewed five sectors in which the term is already firmly established. We found that the prefix “inclusive” is common in the following domains: (1) inclusive development and growth (OECD 2015; Gupta and Vegelin 2016; Jahanger 2023), (2) inclusive (or exclusive) governance and decision-making (OECD 2020; Mustaniemi-Laakso et al. 2023), (3) inclusive cities and urbanization (Gerometta et al. 2005; UN-Habitat 2015; Ramachandran and Di Matteo 2023), (4) inclusive innovation (Foster and Heeks 2013; Government of Canada 2016; Illalba Morales et al. 2023), and (5) inclusive education and workplace (Avramidis and Norwich 2002; Madhesh 2023).

We illustrate the conceptualization of inclusiveness in these five sectors by briefly reviewing one high-profile and international framework for each sector (Table 1). The key insights from these related contexts are as follows. First, inclusiveness has become an important topic in widely varied contexts but has by no means penetrated all academic literature where one could imagine its prominent use, including that of ICCA. The interpretation of “inclusiveness” and “inclusivity” is highly dependent on context. Some sectors represent a means-to-an-end (development, governance, innovation, education), while others are ends-in-themselves (cities and the SDGs). Some are local (cities), while others are national or global (development and the SDGs). Some sectors fall under the domain of law (governance) or economics (innovation), while others fall under the domain of geography (cities) or development (education, growth). We believe that this fragmentation provides an argument for a broader theory of “inclusive inclusiveness”. Second, in terms of commonality, the frameworks can be parsed into three foci of attention: (a) stakeholders, (b) processes, or (c) outcomes, or mixtures thereof. These three terms are often explicitly used within the above frameworks, and they were also dominant in our systematic literature review on ICCA (Pham and Saner 2021). There is a logic to this choice. The three foci represent foundational ideas in public policy, where stakeholders engage in processes to achieve outcomes (Osborne 2010). They also map onto the three major schools of thought in ethics, where virtue ethics informs the attitudes and behavior of stakeholders, deontology informs the duties and rules governing decisions and processes, and utilitarianism informs strategies and the interpretation of results (Waluchow 2003). We note that some frameworks do not cover all three of these foci and, therefore, in that sense, may lack inclusiveness.

Table 1.

| Inclusive Frameworks | Focus(es) | Components/dimensions/principles | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusive development and growth (McKinley 2010) | Processes Outcomes | (i) Human capabilities; (ii) social protection; (iii) income poverty and equity, including gender equity; and (iv) growth, productive employment, and economic infrastructure | Quantitative indicators, illustrated by case studies |

| Inclusive governance and decision-making (UNDP 2007) | Processes | (i) Establishing the human rights normative and legal framework; (ii) applying and enforcing the human rights normative and legal framework; (iii) social mobilization around human rights law | Qualitative indicators, supplemented by case studies |

| Inclusive cities and urbanization (World Bank 2015) | Outcomes | (i) Spatial inclusion to improve access to affordable land, houses, and services for all; (ii) social inclusion to improve democratic processes, protection of rights, and the ability to represent needs, interests, and ideas so that individuals and groups can take part in society; and (iii) economic inclusion that ensures opportunities for all to contribute to and share in rising prosperity | Qualitative indicators, illustrated by case studies |

| Inclusive innovation (UNDP 2020) | Stakeholders Processes Outcomes | (i) Including underrepresented and disadvantaged demographic groups, disadvantaged or lagging regions and districts, low-productivity, traditional or informal sectors, social, economy, community organizations, social enterprises, and cooperatives; (ii) setting priorities for innovation policy and in the regulation of innovation and identifying measures to mitigate the negative impacts of innovation for particular groups and for a more equitable distribution of benefits; (iii) addressing societal challenges and needs, especially the needs of disadvantaged social groups | Both qualitative and quantitative indicators, illustrated by case studies |

| Inclusive education (UNESCO 2017) | Stakeholders Processes | (i) Inclusion and equity are overarching principles in policy, plan, and practices; (ii) education policy documents strongly emphasize inclusion and equity, and senior staffs provide strong leadership; (iii) all services, institutions, and resources support vulnerable learners; (iv) schools encourage all learners’ participation and achievement while teachers receive training and take part in inclusive practices | Qualitative indicators, illustrated by case studies |

Table 2.

| Level of progress | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indicators | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Priority #1: broad approach to moral standing | |||

| Moral standing: clarity To what extent are you clarifying which actors (who or what) should have moral standing? | There is a reliance on current legal standards | There is explicit debate on the scope of all actors whose welfare could be considered (gender, race, age, ability, …) | There are written organizational standards for the scope of actors under consideration |

| Moral standing: breadth To what extent are you broadening which actors (who or what) are given moral standing? | Traditional anthropocentric approaches apply | The well-being of future generations is explicitly considered (e.g., not just “lip service”) | Non-human actors such as sentient animals (or even habitat) are included |

| Priority #2: respect for all knowledge and concerns | |||

| Knowledge: policies To what extent is the principle of respect for all relevant knowledge (e.g., ITK) and concerns embedded in adaptation policies and plans? | Adaptation policies and plans do not state this principle | Adaptation policies and plans clearly state that broad knowledge and concerns should be respected | Adaptation policies and plans clearly show how broad respect for all knowledge and concerns will be implemented |

| Knowledge: practices To what extent is the principle of respect for all relevant knowledges (e.g., ITK) and concerns embedded in adaptation practices? | The principle is implemented in the real world | The level of implementation is evaluated and enforced; stakeholders are engaged | The implementation is resulting in measurable change |

| Priority #3: consideration of differing capabilities and resilience and empowering vulnerable groups | |||

| Vulnerable groups: identification To what extent do adaptation initiatives specifically target vulnerable groups and their need for empowerment? | The initiatives do not explicitly identify vulnerable groups or address their needs | The initiatives tangibly target the needs of vulnerable groups | There is evidence that the initiatives render vulnerable groups more empowered |

| Vulnerable groups: capacities To what extent do adaptation initiatives consider the differences in adaptation capacities and resilience of various stakeholders? | The initiatives do not explicitly consider differences in the adaptation capacities of various stakeholders | The initiatives tangibly address the differing adaptation capacities of various stakeholders | There is evidence that the initiatives enhance the adaptation capacities and resilience of various stakeholders |

| Priority #4: good EDI practices throughout (all staff, all committees) | |||

| EDI: policies To what extent are EDI principles embedded in human resources policies and plans? | Human resources policies and plans do not state EDI principles | Human resources policies and plans include clear EDI principles | Human resources policies and plans include details on how EDI principles will be implemented |

| EDI: practices To what extent are EDI principles embedded in human resources practices? | Human resources staff are fully EDI trained | All staff are EDI trained, and the topic is regularly and openly discussed | Organization-wide EDI performance is formally assessed by external auditors |

| Priority #5: science and education policy for all: access and representation (including open procurement and inclusive subsidies) | |||

| Science policy: procurement To what extent do major science and education policies aim at open procurement (contracts, grants, and employment)? | Major science and education policies include components or versions of open, inclusive procurement | Major science and education policies contain a clear plan for how open, inclusive procurement will be realized | There is evidence that procurement is becoming more open and inclusive |

| Science policy: subsidies To what extent are policies on subsidies informed by the principles of inclusive education and science for all? | Policies on subsidies include principles of inclusive education and science for all | Policies on subsidies contain a clear plan for how inclusive education and science for all will be realized | There is evidence that science and education subsidies are becoming more inclusive |

| Priority #6: transparent, accessible, and collaborative standards, activities, and communications | |||

| Implementation: access To what extent are adaptation projects and processes transparent and is information accessible to all? | Policies and processes foster transparency | Policies and processes are implemented with inclusive accessibility in mind | There is evidence that inclusive forms of access are achieved |

| Implementation: collaboration To what extent are adaptation projects collaboratively developed and implemented? | Projects include components that facilitate collaboration between individuals and organizations | Projects are collaboratively developed and implemented | There is evidence of satisfaction with the process (relevant knowledge and values were used) |

| Priority #7: use of inclusive values to define “success” and to develop performance indicators | |||

| Outcomes: success To what extent are the definition of success and the development of performance and impact indicators informed by inclusive values? | The conception of success and performance indicators is designed from an inclusive perspective | If performance indicators are changed during implementation, then these changes are evaluated from an inclusive perspective | There is evidence that the performance indicators used for long time series are informed by inclusive values |

| Priority #8: open access to data and results | |||

| Outcomes: open access To what extent are climate change data and adaptation project data (including results) available to and accessible by everyone? | Open access policies are designed from an inclusive perspective (jargon, format, access) | Open access policies are implemented from an inclusiveness perspective (jargon, format, access) | There is evidence that access and usage by the full diversity of interested parties are improving |

| Priority #9: diversity and representation in evaluation and audit | |||

| Outcomes: audit To what extent are evaluation and audit bodies, and the standards they use, inclusive? | Audit bodies and their standards are designed for inclusiveness | Audit bodies practice inclusiveness in their training and work | There is evidence that the audit process and result correspond to principles of inclusiveness |

Third, we observe that case studies are commonly used to illustrate indicators and ethical perspectives. Without taking away from the value of case studies, we argue that there is value in an argumentative, theoretical approach to add insights to what is already understood from practice. Given that inclusion is heavily linked to ethical considerations, there is clearly “moral corruption” (Gardiner 2022). At the same time, this gap in theoretical approach provides an opportunity for improvement by elaborating ethical thinking during the development of inclusion-related frameworks and engaging the perception, implementation, and evaluation of inclusiveness with issues in ethics and philosophy more generally.

Moral reasoning for ICCA

In this section, we investigate the relevant ethical principles and considerations to answer the question: What are “good stakeholders”, “good processes”, and “good outcomes” for ICCA? The emphasis of the word “good” is inspired by G.E. Moore's definition (1903): “Ethics is the inquiry into what is good”. The word “good” is, in this view, a moral ideal.

We first investigate climate change ethics to find the most fundamental principles and considerations that shed light on our analysis. At the heart of climate change ethics are the principles of justice and caring that raise the key moral reasoning aspects of ICCA.

The multifaceted concept of climate justice refers to global justice, inter-generational justice, and ecological justice (Gardiner 2011, 2022). Global justice deals with vulnerable and affected people in the present whose rights could be violated by the decisions of others (governments, industries, groups, and individuals), while they are powerless to block these decisions. This undermines their vital interests. Inter-generational justice concerns the interests of future people who are currently non-existent and powerless, but they will be moral agents in the future and are thus worthy of respect and the granting of universal human rights. Ecological justice emphasizes the responsibilities of human beings to refrain from transferring the burden to the environment and supports the well-being of non-human actors, animals, plants, and ecosystems due not only to their instrumental value but also their intrinsic value. Some authors also argue for the importance of recognition justice, which requires respecting and acknowledging the cultures, values, and situations of all affected parties who should be considered and represented throughout decision-making processes when it comes to distributional, procedural, and compensational justice (Schlosberg 2012; Hourdequin 2016).

Indigenous ethics and feminist care ethics provide a care-based approach to justice that has been intensified in climate change ethics. Instead of focusing on rights, duties, or responsibilities, these strands of ethics refer to guidance for ethical decision-making about action and policy that are grounded in the virtues, practices, and knowledge associated with appropriate caring and respect for self and others (Gilligan 1982; Held 2006). These theories accelerate inclusive relations of caring within interdependent human and ecological communities, justifying ethical responsibilities for all human and non-human entities (Whyte 2020; Tschakert et al. 2021). Through these intimate relationships, Indigenous peoples and female groups produce and strengthen crucial ecological and local knowledge that must be respected and included to inform conservation strategies, environmental change adaptation, and resilience. Moreover, the ethics of caring also advocate for the empowerment of less powerful groups and communities to actively include themselves in these processes, thus caring for the social and ecological communities in which their lives and interests are interwoven (Tschakert and Machado 2012).

CCA initiates, happens, and manages within a form of organization, whereas the inclusiveness perspective in CCA is based on the ethical systems that are predominantly influenced by several characteristics of human connection, such as politics and culture. With our efforts to operate inclusiveness in CCA practices, we have extended this concept by supplementing it with organizational, institutional, and political perspectives. From an organizational perspective, inclusiveness emphasizes the importance of respecting differences in culture and values, acknowledging the systemic inequality and vulnerability that prevent certain groups from raising their voices, and shaping adaptation processes and outcomes that are just. From an institutional perspective, inclusiveness focuses on the ways in which those who are vulnerable and marginalized seek to address distributional and procedural injustice. From a political perspective, inclusiveness highlights the interaction and deliberation between groups to assert their status in the political community. We supplemented our analysis by looking into organization or business ethics and political ethics to explore principles for what makes “good stakeholders”, “good processes”, and “good outcomes”.

Rooted in business ethics, EDI has recently been used as a phrase by organizations to emphasize ongoing efforts to rectify the problems that are linked to the EDI of staff, the focus of which has broadened from gender to include other underrepresented groups (Wolbring and Lillywhite 2021). Equity aims to ensure that everyone has an equitable chance to succeed. Diversity promotes the active participation of individuals from a wide range of backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives, while inclusion emphasizes the importance of creating environments where all individuals feel valued, respected, and empowered (Oswick and Noon 2014; Garg and Sangwan 2021). EDI explicitly acknowledges that different individuals may require different levels of support or accommodations to achieve fairness and contribute their unique perspectives and talents to the development of organizations. EDI serves as the organizational perspective of ICCA. By maximizing opportunities for the full pool of potential participants, EDI helps organizations promote innovation and creativity, increase effectiveness, and strengthen the relevance and impact of their adaptation actions.

Political ethics revolves around the moral principles, values, and standards that guide the behavior and actions of individuals and institutions in political decision-making and governance (Thompson 2019). Collaborating and positively contributing to the well-being and welfare of a broad society are acknowledged as social responsibilities of political actors, institutions, and citizens (Digeser 2022; Mozumder 2022). Political ethics emphasizes transparency and accountability for public officials and institutions to answer for their actions to the public while also promoting the establishment of mechanisms and institutions that ensure accountability, such as independent oversight bodies (Fox 2007; Vian 2020). Collaboration, co-contribution, transparency, and accountability serve as the institutional perspectives of ICCA. Meaningful inclusion explicitly requires collaboration between stakeholders to carry out collective action for adapting to a changing climate while accelerating the values of accountability and transparency to maintain just and equitable processes and outcomes throughout adaptation practices.

The three-pillar framework informed by climate change ethics, business ethics, and political ethics provides a valuable foundation for moral reasoning in the context of ICCA. Climate change ethics contributes to the principles of justice and caring; business ethics provides insights on equity, diversity, and inclusion; and political ethics highlights the value of collaboration, transparency, and accountability. Together, these principles can guide decision-makers and stakeholders in developing and evaluating inclusive adaptation strategies. Based on the above ethical points, (1) we answered the question: What are “good stakeholders”, “good processes”, and “good outcomes” for ICCA? and (2) we identified the following four core components of ICCA.

1.

Good foundations: An inclusive approach to CCA should promote justice and caring in the broadest sense of these concepts. CCA should ensure justice for different groups in the current world, especially systemically marginalized groups, people in the future, and non-human actors. CCA should intensify respect for and mutual acknowledgement of different cultures, values, and knowledge and promote meaningful cooperation between them throughout the adaptation circle.

2.

Good stakeholders: A more inclusive approach to CCA requires the implementation of equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) policies throughout organizations and communities involved in CCA. EDI can be considered as the organizational guideline for ICCA. On the other hand, providing good support is a sufficient condition to improve stakeholders’ capacities and contributes to EDI practice and ICCA in general. Some examples include broad access to research grants, knowledge mobilization and data, CCA or development support, subsidies, and benefits, which are key ethical issues. Access issues should be understood in their broadest form (intentional, unintentional, technical, and geographical) and to various forms of support (subsidies, compensation, procurement opportunities, research, and data).

3.

Good processes: This means incorporating inclusiveness into the CCA processes, from ideation to implementation. Developing broad collaboration but ensuring transparency and accountability in all matters of governance and the exercise of power is an ethical and democratic priority to ensure that CCA can occur in an inclusive way throughout the processes of stakeholder identification, direction setting, consultation, decision-making, review, and appeal powers.

4.

Good outcomes: The good outcomes of ICCA could be perceived as the contribution of inclusiveness to the general outcomes of CCA, ensuring all outcomes of adaptation are truly inclusive. Good outcomes are the direct result of the three above-mentioned components, good foundations, good stakeholders, and good processes. This includes caring for the most vulnerable groups, ensuring justice for future people and more-than-human actors, showing respect for different cultures, values, and knowledge, reinforcing organizational inclusion, developing need-based support policies, and strengthening collaboration and accountability.

We conclude, therefore, that the framework is reasonably inclusive when it covers the moral principles rooted in different ethics theories as well as the ethical considerations of organizations and institutions for adaptation in practice. All four themes must be considered in concert to attain “inclusive inclusiveness” because they interact with each other. A strong emphasis on one theme (for example, the breadth of the moral circle) will impact others (for example, support and process). We will say more about the trade-off between what is theoretically desirable and what is practically achievable in the Discussion and conclusion section of this paper.

Developing a framework for ICCA: 9 proposed priorities and 15 proposed indicators

In public policy, so-called logic models are commonly used to plan activities and develop indicators of success (W.K. Kellogg Foundation 2004). The six common steps of logic models are broad enough to cover all of the key processes of general policymaking and specific adaptation initiatives. ICCA asserts the importance of inclusiveness throughout all steps: (i) planning; (ii) inputs (resource allocation and management); (iii) activities (implementation); (iv) outputs (results); (v) impacts (success); and (vi) evaluation and learning.

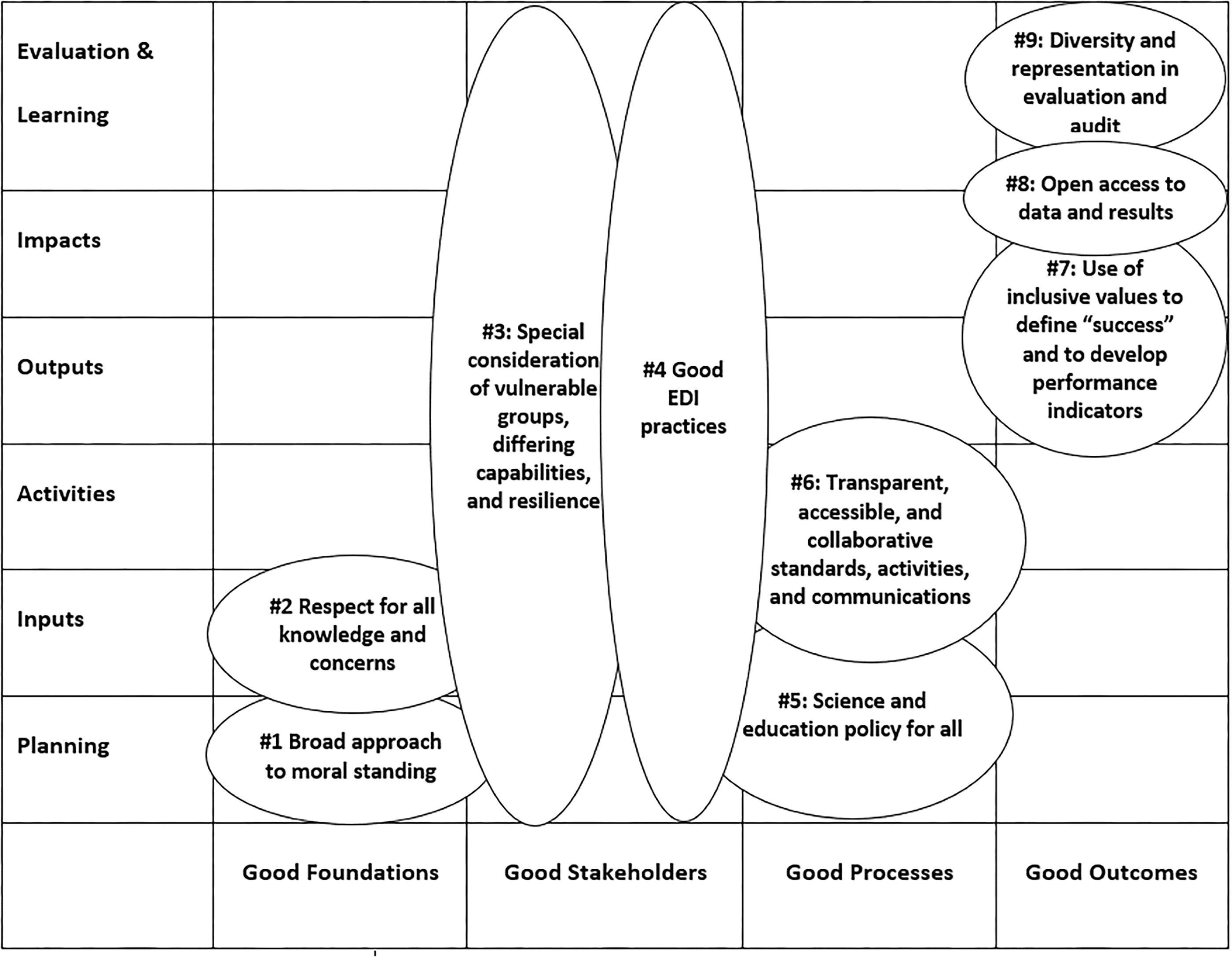

These six steps could be juxtaposed with the four key themes identified in the previous section in a heuristic matrix. Such a 6 by 4 matrix, however, would have an overwhelming, and overlapping, set of possible 24 units of concern. We opted instead to propose nine priorities guided by both the inclusiveness and climate change literature, the gap in adaptation practices, and the potential contribution to adaptation debates. The following section presents a summary chart (Fig. 1) aimed at giving a broad sense of relationships, followed by a description of each of the nine priorities.

Nine proposed priorities

Priority #1: broad approach to moral standing

Priority #1 focuses on establishing a good foundation for inclusive adaptation planning. Foundational to ethics, and in particular environmental ethics, is the identification of entities with moral standing. That is to say, the identification of whose interests, welfare, or fate needs to be considered in deliberations (Schönfeld 1992; Jaworska and Tannenbaum 2021). To take inclusiveness seriously, we would argue, requires an explicit debate on who or what has moral standing.

Answering this question is the initial step and will inform the scope of the entire public policy exercise. In an anthropocentric moral system, only human beings have moral standing, meaning humans are ends-in-themselves and should never be viewed as instruments to an end. More extremely, this scope is even further reduced, wherein moral standing is granted only to adults, or adults capable of decision-making, as well as to citizens, consumers, and so forth. Climate change ethics, with its greater focus on intergenerational justice and ecological justice, explicitly argues for a further extension of the moral circle to future people and non-human actors. Future people will be moral agents and are thus worthy of respect and deserve to have universal human rights (Gardiner 2011, 2022). Any entity capable of pain and pleasure (for example, all mammals and birds) should have their interests considered with the like interests of humans (Bentham 1789; Singer 1974) ). The extension, it can be argued, should be taken even further to include endangered species, biodiversity, and even habitat or land (Taylor 1986; Callicott 1989; Hayward 2006).

Inclusiveness indicators within this priority should first track whether a real consideration of moral standing is even taking place. While the essence of considering future people in present adaptation practice has become common, participants may feel that a debate over speciesism is academic, inappropriate, distracting, or unnecessary. We disagree and note that many climate change activists are vegetarians, either to reduce the carbon footprint of food or to reduce pain and suffering caused to animals, or both (Boucher et al. 2021). Even for components of the land, the idea of moral consideration (moral standing) is gaining traction. For example, it has become a practical reality to have political representation of rivers in New Zealand's parliament (Dwyer 2017).

Priority #2: respect for all knowledge and concerns

Priority #2 focuses on establishing a good foundation for inclusive adaptation inputs. The decision of who or what has moral standing should extend to respecting the knowledge and cultures that different actors bring to the table.

The inclusion of diverse cultures, values, and knowledge can certainly be perceived as a moral command and a competitive advantage for adaptation activities (Byskov et al. 2021; Martin et al. 2022). On the one hand, as different actors are influenced by climate change, which includes local organizations, vulnerable groups, and Indigenous communities, they all have the right to contribute to shaping these adaptation decisions. On the other hand, it is widely acknowledged that they possess crucial cultures, values, and knowledge that can enrich and benefit adaptation planning and implementation. Including different actors’ values, concerns, and perspectives is key to ensuring the relevance and legitimacy of decision-making for CCA (Cash et al. 2002; Adger et al. 2017).

For example, within Indigenous worldviews, non-human entities and ecosystems are agents and have the same equal rights as humans (Smith 2017; Charpleix 2018). Since climate change also threatens the well-being of ecosystems and non-human beings, these worldviews support adaptation policies and actions that extend protections beyond an anthropocentric scope and respect the rights of non-human actors to adaptation and resilience (Ford et al. 2016). Local practices, such as traditional agricultural practices, often lead to better adaptation outcomes (Parraguez-Vergara et al. 2018), and local knowledge, such as Indigenous knowledge on managing wildfire, often leads to more sustainable adaptation (Mistry et al. 2016).

Inclusiveness indicators within this priority should track both intent and delivery and should be deployed early in the policy process, at the earliest steps of the logic model.

Priority #3: special consideration of the differences in vulnerabilities, capabilities, and needs and empowering marginalized groups

Priority #3 focuses on establishing good stakeholder management throughout inclusive adaptation processes, grounded on the principles of equity and caring for less advantageous groups. Vulnerability and adaptation capacities are useful concepts to emphasize here. Vulnerability, defined as a situation in which “a person or community is not able to cope and adapt to climate-related hazards” (IPCC 2022b), depends on both exposure to hazardous climate change effects and the ability of the impacted system to adapt (Smit and Wandel 2006). By supporting adaptive capacity through the provision of a system that furnishes less advantaged people with what they need to adapt, the adverse impacts of climate change may be reduced while the beneficial impacts are enhanced (Smit and Pilifosova 2001). Unfortunately, neither vulnerabilities nor capacities are uniform, as they are characterized by systemic inequalities. Therefore, they require special attention in the context of inclusiveness.

Efforts should be made to understand how to measure and support capability building for groups and communities, especially the vulnerable ones, and how such capabilities will foster their adaptive capacity for climate change. This is one of the most effective ways to achieve the inclusion of socially vulnerable populations as full participants who possess the agency to shape the decisions that affect them (Malloy and Ashcraft 2020). Capabilities that are critical to effectively responding to climate change may include access to education, healthcare, technology, social support, and public services, which can directly support adaptation. For example, capacity-building activities such as providing information on the impact of climate change on yields and livelihoods or building cultivation skills and knowledge to combat climate variability have been considered as critical determinants of adaptation in that they actively involve farmers in the processes of minimizing the negative impacts of climate change (Tahiru et al. 2019).

Inclusiveness indicators within this priority should cover how adaptation initiatives recognize differences in the vulnerabilities, adaptation capacities, and needs of various stakeholders, as well as their efforts to empower the most vulnerable groups.

Priority #4: good EDI practices (for all staff and committees)

Priority #4 focuses on establishing good stakeholder management for inclusive adaptation processes based on EDI (equity, diversity, and inclusion) practices. EDI has emerged as a prominent principle in contemporary human resource management (Özbilgin and Chanlat 2017). Attention to equity leads to consideration of context and diverging needs. Diversity is often portrayed as the “what” of EDI; it describes a desired composition of a team, committee, or workforce. Inclusion is often portrayed as the “how”, that is, the means by which diversity is achieved (Burg 2018). In the case of CCA and climate justice, even if the term “EDI” is not commonly discussed, the interest in diversity and non-discrimination usually exists, and may be expressed in other languages (Jafry et al. 2018).

EDI may address gender, race, disability, or any other form of potential discrimination. In any organization, including those that are carrying out adaptation, EDI should be considered not only during the hiring of individual staff but also during the formation of committees as well as in the contexts of working with outsiders, the formulation of public communications, and so forth. EDI should be credible as a moral commitment and should stand as a cultural norm that thoroughly penetrates an organization (Anand 2021).

Inclusiveness indicators within this priority should cover both policies and practices and should evaluate how broadly the EDI principles penetrate the entire organization (beyond the HR department).

Depending on the direction that is selected in determining who or what has moral standing, inclusion may require representation, either formal or informal, from those who cannot participate. Examples would be adults living with disabilities, children, future generations, sentient animals, habitats, and so forth. EDI in representation creates special challenges when the moral circle is cast widely. Inclusiveness indicators should cover these considerations as well; for example, who exactly should represent the long-term interests of children in a climate change context?

Priority #5: science and education policy for all: access and representation (including open procurement and inclusive subsidies)

Priority #5 focuses on establishing good processes for inclusive adaptation planning and inputs. Once inclusiveness is taken seriously, many traditions are challenged. One example is scientific research, which is either conducted in-house by governments, subsidized directly through grants, or subsidized indirectly through the financing of universities. The beneficiaries are, for good reasons, the experts who are capable of providing the required services. This is a difficult and touchy issue because the very idea of expertise is non-inclusionary. We cannot have the “select” and the “non-select” at the same time. Similar to political systems where the elected leaders act as representatives for the masses, the experts act to represent knowledge. However, if one is serious about the inclusion of all value systems and all knowledge, the expert model needs to be reconsidered (Jasanoff 1998).

Two reasons for a move toward greater inclusion are improved representation and improved access to benefits. If an organization, for instance, actively seeks the inclusion of ITK, it will not only broaden its access to values and knowledge, but it will also provide broader access to procurement (contracts, grants, and employment) and subsidies (for institutions of all kinds).

Therefore, inclusiveness indicators within this priority should evaluate whether subsidies to universities, colleges, and other institutions should be informed by the goal of broad inclusiveness and non-discrimination and how open the access is to contracts, grants, and employment.

Priority #6: transparent, accessible, and collaborative standards, activities, and communications

Priority #6 focuses on establishing good processes for inclusive adaptation activities. Like other policymaking steps, implementation benefits from public input. The implementation should be considered with inclusiveness in mind. Here too, collaborative approaches to include values, interests, viewpoints, and knowledge should be an ambition toward greater inclusiveness in CCA (Walsh 2019; Smucker et al. 2020; Maldonado et al. 2021; Tagliari et al. 2021).

Ensuring transparency and accountability is obvious by including a larger group and a diversity of interested parties (Bowen et al. 2017; Blasiak et al. 2019; Berger et al. 2021). However, mechanisms to ensure transparency and accountability in implementing, monitoring, and evaluating adaptation are lacking across scales and contexts, for example, in the health sector, water management, forest-based adaptation, and disaster risk management (Schipper et al. 2022).

Simply posting materials to the Internet does not necessarily achieve the goal of transparency. Access hurdles of various types need to be considered: Who is not able to access the Internet? Are the materials broadly comprehensible? Is the necessary filter being applied to what can and what cannot be posted, creating a bias with respect to content and access? (Saner 2006). Once a good measure of transparency is achieved, meaningful forms of inclusive debate, collaboration, and even partnerships can be developed.

Priority #7: use of inclusive values to define “success” and to develop performance indicators

Priority #7 focuses on establishing good outcomes that inclusiveness can contribute to adaptation success. For example, the discussion of moral standing has a direct effect on the conception of success, especially in an environmental and long-term context such as CCA, where it cannot be taken for granted who gets to define what success is. The conception of adaptation success varies and is even contested between different groups of currently living people, present people versus future people, and human actors versus more-than-human actors.

In practice, interventions aimed at CCA and vulnerability reduction sometimes inadvertently reinforce, redistribute, or create new sources of vulnerability. A lack of critical engagement with how to define adaptation success has been highlighted as one mechanism driving these maladaptive outcomes (Eriksen et al. 2021). This lack of critical engagement is the failure of results-based management, which seeks to define clear goals and demonstrate evidence of success from the perspective of donors in the context of development aid (Dilling et al. 2019). More importantly, it is the failure of inequitable systems of power and participation processes that marginalizes less-powerful actors and especially vulnerable groups in making normative judgments of what constitutes adaptation success. One example is the National Adaptation Programs of Actions (NAPAs), within which rural residents’ needs and the views of local institutions are likely to be obscured (Ayers 2011).

As a result, success and the system of performance indicators for adaptation success need to be understood and developed through an inclusive lens. Inclusiveness indicators within this priority would evaluate both the performance indicators and the actual impacts of the activity.

Priority #8: open access to data and results

Priority #8 focuses on establishing a good outcome that inclusiveness can contribute to adaptation impacts. The increasing commitment by many governments to support open access to data and results corresponds to an inclusiveness goal (Swan 2012; Roche et al. 2020). A wider variety of individuals and local communities can benefit from climate change research and data. More and higher quality climate risk data, for instance, could support local people and communities to lower exposure and mitigate impact. Information can be used for new goals. This is akin to the patent system that was introduced to promote disclosure with the aim of spurring further innovation. It is noteworthy that the advent of open data represents a new area of transparency and inclusiveness.

However, the Internet, social media, and echo chambers have not led to the democratization of decision-making that many had hoped for (Schirch 2021). Important access hurdles may still exist (Lund 2019). For example, public funding research data and results often lack detail, updates, and ready-to-use data. Data are normally on a large scale, like a national or regional scale, and sometimes it is very scientific and requires skill and knowledge to analyze and interpret these data into useful information to enable better decision-making for households and communities. Private funding databases require membership fees or access fees.

Inclusiveness indicators within this priority would evaluate both the efforts made toward open access and the remaining hurdles to access.

Priority #9: diversity and representation in evaluation and audit

Priority #9 focuses on establishing another good outcome that inclusiveness could contribute to adaptation monitoring and evaluation. The focus on independence and impartiality of evaluators and auditors from the organizations they study that helps reduce conflicts of interest is dominant in monitoring and evaluation literature and practice (Adelopo 2016). However, the question of the equity, diversity, and inclusiveness of the audit body and process should not be put in a secondary position.

The individuals or committees that comprise the auditor function may be lacking in diversity and inclusion, and if that is the case, it should be noticed and corrected. It is also possible that the written or unwritten standards used to perform the audit will be insufficiently inclusive. This is especially likely if the organization under audit breaks new ground when it comes to the breadth of the moral circle (by including entities that normally would not enjoy moral standing). Organizations may be ahead of professional auditors, and thus the question arises as to whether the external auditors are equipped to evaluate the impact on, say, future generations, sentient animals, or the land?

Inclusiveness indicators within this priority would evaluate both the diversity of the audit body as well as their standards and practices.

Fifteen proposed indicators

We propose below, as the basis for discussion and future research, a set of draft indicators to evaluate inclusiveness in CCA. These indicators are non-quantitative and function as checklists. The goal is to encourage the user to “think inclusively about inclusiveness” and to push the boundaries when it comes to stakeholder selection, process design, and the conceptualization and evaluation of outcomes. Indicators follow the same order as the nine priority areas identified in the previous section (with one to two indicators per priority). Based on preliminary discussions with stakeholders and practitioners, we are convinced that these indicators are testable in practice and strong motivators for helpful debate.

Discussion and conclusion

We are beginning this section with a discussion of trade-offs. We know a priori that implementing inclusiveness entails direct or opportunity costs. The most obvious costs are the increased administrative burden, the loss of time, and the loss of focus. One could argue that idealistic versions of inclusiveness are in direct conflict with the formulation of priorities, something most project and people managers value highly (discriminating what matters most is more productive than including everything). The capacity for identifying priorities is of particular importance during any crisis, including that of climate change. In response, we would argue that thinking inclusively is a better starting point for priority selection and priority sequencing. A broader initial scope does not need to result in a loss of focus, and the time spent upfront identifying good (justified and sustainable) priorities will save more time later. It is also plausible that inclusive governance will be more effective because it draws from diverse knowledge and will be more sustainable because of the broader acceptance of direction.

A further consideration is the potential clash between inclusiveness and culture, tradition, or “moral order”. This is a challenging topic, given the global scope of climate change. It is a certainty that views on inclusiveness will differ between, say, Afghanistan and New Zealand. In this context, one also needs to expect that a regime will preach inclusiveness and implement something different. We do not have a good solution to this problem. Inclusiveness is a democratic and liberal concept that will not be universally accepted. The question of how elitist or non-elitist a political system ought to be goes back to at least Plato's Republic.

As a second discussion point, we would like to state the obvious point that it is impossible to achieve perfect inclusiveness. Just as extreme reduction leads to the absurd (reductio ad absurdum), extreme expansion would be far from convincing or practical. Our selection of nine focal areas was made with this problem in mind. We are attempting a breadth of inclusiveness that is neither exotic (except for the possible point about non-anthropocentric thinking) nor impractical.

We aimed to not only provide an overview of common components, such as discrimination, but to also seek a more complete approach to building an integrative lens. We start very wide when working with ethical and public policy concepts, then we select priorities and indicators, and, finally, we will improve and narrow further during interviews with CCA practitioners (on-going and planned research).

The ultimate goal is to promote inclusiveness in a broad way, across themes and across the steps of a policy process. This should improve coordination and efficiency. It should also reduce duplication and counter-purpose initiatives. We seek to achieve organizational learning in several distinct ways that target common inclusiveness limits. To illustrate these limits, we have to distinguish between omission and commission as well as involuntary and voluntary acts, as illustrated in the matrix in Table 3.

Table 3.

| Nature of act | Involuntary | Voluntary |

|---|---|---|

| Omission | We do not see any lack of inclusiveness: | We see the lack of inclusiveness, but we do not care enough to act: |

| “Blind spots” > Learn to see | “Callousness” > Learn to care | |

| Commission | We see the lack of inclusiveness and we care, but we lack the capacity to overcome it: | We see the lack of inclusiveness and we care. We have tried to overcome it and decided to give up: |

| “Constraint” > Learn to make it happen | “Defeat” > Learn to persevere |

Working with the above inclusiveness indicators, we argue, will improve learning against all four limits: blind spots, callousness, constraint, and defeat.

Discussing the questions in Table 3 should take care of the first problem, blind spots. We use blind spots here as a scientific term to express the situation in which people cannot recognize the perpetuation of exclusion and discrimination. This will not be achieved, however, if the indicators are merely part of a bureaucratic exercise. They must be presented as real issues that deserve the time and attention of debate. The dialogue should involve diverse participants, which, if patiently led, should improve understanding and empathy and thus reduce the second limit, callousness. Imagine a conversation on the topic of Indicator 1 (Who has moral standing?). Such a conversation should open everybody's eyes to the fact that ignoring the pain or suffering of any sentient being (humans of all kinds and sentient non-humans) is difficult to justify. While it may be likely that participants would disagree on the moral status of animals, the disagreement would nonetheless open a people's eyes to the breadth of values held by a community. Because the suite of 15 indicators also contains many references to implementation and performance measurement, it should be possible to also push boundaries on the “constraint” and “defeat” limits. Based on the awareness created by such dialogue, it ought to become more realistic to achieve “inclusiveness-by-design”, which would improve the ability to persevere and succeed.

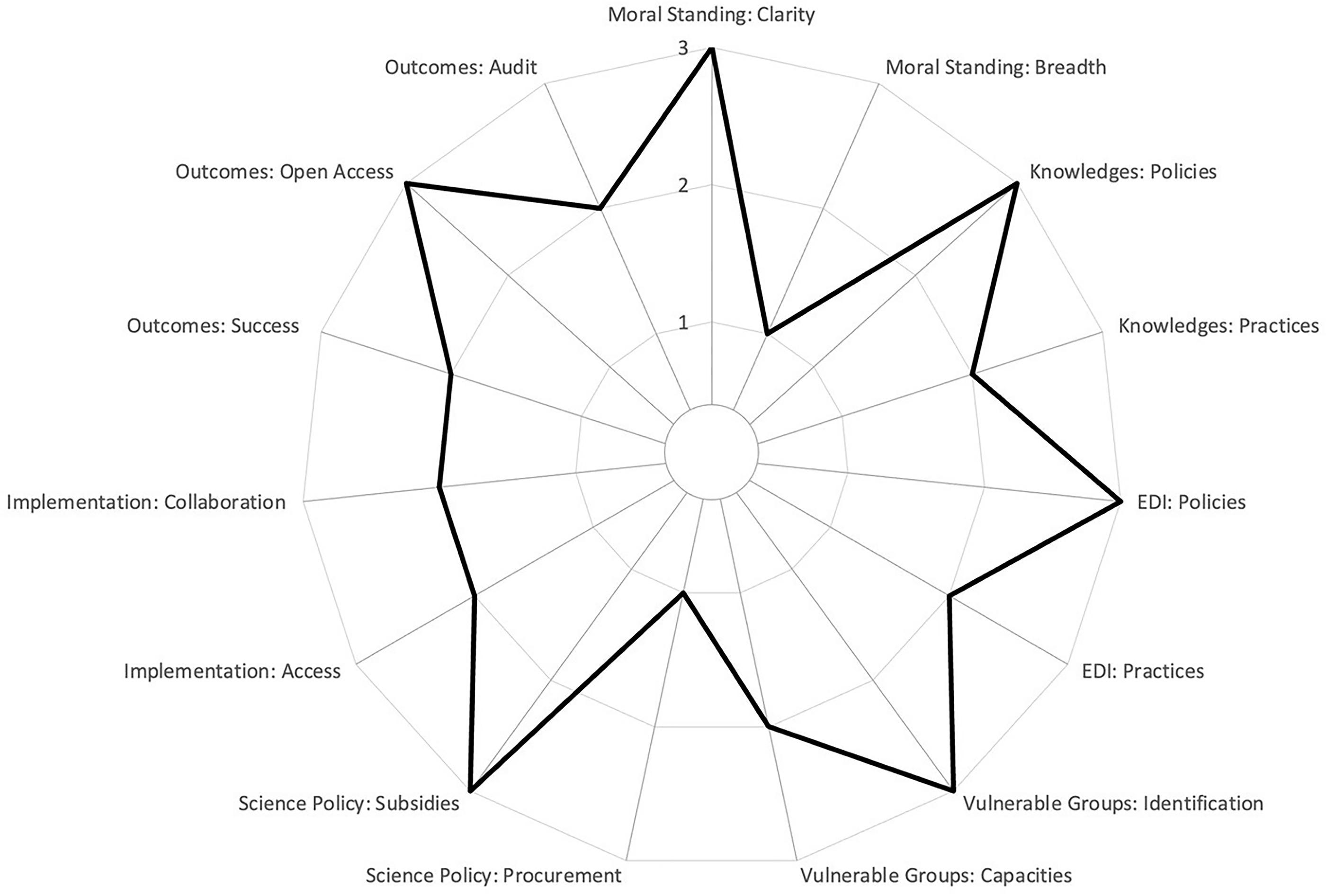

An important side benefit of such debates about values and ethics is that they build a common understanding and common culture that can benefit the operation in other contexts. A checklist such as that in the above table is essential to the evaluation process. However, the answer to these questions can lead to a presentation challenge. A visual picture of the results can be helpful. Inspired by the Korn Ferry Diversity and Inclusion Maturity Model (Korn Ferry 2021), we produced sample Fig. 2. In contrast to the elaborate Korn Ferry Model, we selected a very basic “Radar Chart” because these charts can be easily generated in standard software packages. Visuals that summarize all 15 indicators in one chart can help one to make comparisons over time and across comparable organizations.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Theory can only provide a framework and a starting point for practical work. Making adaptation more inclusive requires the testing of the 9 priorities and 15 indicators in real-life, diverse settings. It will be necessary to interview policymakers, researchers, and practitioners on the inclusiveness of adaptation processes, the potential of applying the inclusiveness framework in adaptation research, policymaking, and practice, as well as the necessary adjustment of inclusive indicators to be applicable. This work is currently underway.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ozan Gurcan for his comments and for suggesting the addition of a radar chart. The usual disclaimers apply.

References

Adelopo I. 2016. Auditor independence: auditing, corporate governance and market confidence. Routledge, London.

Adger W.N., Butler C., Walker-Springett K. 2017. Moral reasoning in adaptation to climate change. Environmental Politics, 26(3): 371–390.

Anand R. 2021. Leading global diversity, equity, and inclusion: a guide for systemic change in multinational organizations. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Oakland.

Avramidis E., Norwich B. 2002. Teachers’ attitudes towards integration /inclusion: a review of the literature. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 17(2): 129–147.

Ayers J. 2011. Resolving the adaptation paradox: exploring the potential for deliberative adaptation policymaking in Bangladesh. Global Environmental Politics, 11(1): 62–88.

Bentham J. 1789. An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation . T. Payne, London.

Berger S., Owetschkin D., Fengler S., Sittmann J. (Editors). 2021. Cultures of transparency: between promise and peril. Routledge, London.

Berry P., Schnitter R. (Editors). 2022. Health of Canadians in a changing climate: advancing our knowledge for action. Government of Canada,Ottawa, ON.

Blasiak R., Wabnitz C.C.C., Daw T., Berger M., Blandon A., Carneiro G., et al. 2019. Towards greater transparency and coherence in funding for sustainable marine fisheries and healthy oceans. Marine Policy, 107: 103508.

Boucher L.J., Kwan G.T., Ottoboni G.R., McCaffrey M.S. 2021. From the suites to the streets: examining the range of behaviors and attitudes of international climate activists. Energy Research and Social Science.

Bowen K.J., Cradock-Henry N.A., Koch F., Patterson J., Häyhä T., Vogt J., Barbi F. 2017. Implementing the “Sustainable Development Goals”: towards addressing three key governance challenges—collective action, trade-offs, and accountability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 26–27: 90–96.

Burg N. 2018. Diversity and inclusion: what's the difference, and how can we ensure both? [Online]. Available from https://www.forbes.com/sites/adp/2018/06/25/diversity-and-inclusion-whats-the-difference-and-how-can-we-ensure-both/#:~:text=Mitjans%3A%20Diversity%20is%20the%20%E2%80%9Cwhat,that%20enables%20diversity%20to%20thrive [accessed 6 November 2023].

Byskov M.F., Hyams K., Satyal P., Anguelovski I., Benjamin L., Blackburn S., et al. 2021. An agenda for ethics and justice in adaptation to climate change. Climate and Development, 13(1): 1–9.

Callicott J.B. 1989. In defense of the land ethic: essays in environmental philosophy. State University of New York Press, New York.

Cash D., Clark W.C., Alcock F., Dickson N.M., Selin N.E., Jager J. 2002. Salience, credibility, legitimacy and boundaries: linking research, assessment and decision making. Faculty Research Working Papers Series, November 2002. John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge.

Charpleix L. 2018. The Whanganui River as Te Awa Tupua: place-based law in a legally pluralistic society. The Geographical Journal, 184(1): 19–30.

Chu E.K., Cannon C.E. 2021. Equity, inclusion, and justice as criteria for decision-making on climate adaptation in cities. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 51: 85–94.

Digeser P.E. 2022. Collaboration and its political functions. American Political Science Review, 116(1): 200–212.

Dilling L., Prakash A., Zommers Z., Ahmad F., Singh N., Wit S., et al. 2019. Is adaptation success a flawed concept? Nature Climate Change, 9: 572–574.

Dwyer C. 2017. A New Zealand river now has the legal rights of a human [Online]. Available from https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/03/16/520414763/a-new-zealand-river-now-has-the-legal-rights-of-a-human [accessed 6 November 2023].

Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2022. 2030 Emissions reduction plan: Canada's next steps for clean air and a strong economy. [Online]. Available from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/eccc/documents/pdf/climate-change/erp/Canada-2030-Emissions-Reduction-Plan-eng.pdf.

Eriksen S., Schipper E.L.F., Scoville-Simonds M., Vincent K., Nicolai Adam H., Brooks N., et al. 2021. Adaptation interventions and their effect on vulnerability in developing countries: help, hindrance or irrelevance? World Development, 141: 105383.

Ford J.D., Cameron L., Rubis J., Maillet M., Nakashima D., Willox A.C., Pearce T. 2016. Including indigenous knowledge and experience in IPCC assessment reports. Nature Climate Change, 6(4): 349.

Foster C., Heeks R. 2013. Conceptualising inclusive innovation: modifying systems of innovation frameworks to understand diffusion of new technology to low-income consumers. The European Journal of Development Research, 25(3): 333–355.

Fox J. 2007. The uncertain relationship between transparency and accountability. Development in Practice, 17(4/5): 663–671.

Frechtling J.A. 2015. Logic model. In International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Edited by J.D. Wright. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. pp. 299–305.

Gardiner S.M. 2011. A perfect moral storm: the ethical tragedy of climate change, environmental ethics and science policy series. Online ed. Oxford Academic.

Gardiner S.M. 2022. Environmentalizing bioethics: planetary health in a perfect moral storm. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 65(4): 569–585.

Garg S., Sangwan S. 2021. Literature review on diversity and inclusion at workplace, 2010–2017. Visionary, 25(1): 12–22.

Gerometta J., Haussermann H., Longo G. 2005. Social innovation and civil society in urban governance: strategies for an inclusive city. Urban Studies, 42(11): 2007–2021.

Gilligan C. 1982. In a different voice: psychological theory and women's development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Government of Canada. 2016. An inclusive innovation agenda: the sate of play [Online]. Available from https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/062.nsf/eng/00014.html [accessed 6 November 2023].

Grant P. (Editor). 2019. Minority and Indigenous trends 2019: focus on climate justice. Minority Rights Group International. [Online]. Available from https://minorityrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/2019_MR_Report_170x240_V7_WEB.pdf [accessed 6 November 2023].

Gupta J., Vegelin C. 2016. Sustainable development goals and inclusive development. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16(3): 433–448.

Hayward T. 2006. Ecological citizenship: justice, rights and the virtue of resourcefulness. Environmental Politics, 15(3): 435–446.

Held V. 2006. The ethics of care. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

Hoicka C.E., Zhao Y., Coutinho A. 2022. Philanthropic organisations advancing equity, diversity and inclusion in the net-zero carbon economy in Canada. McConnell Foundation, Canada. Available from https://mcconnellfoundation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/EDIA-in-Climate-Action-in-Canada.pdf [accessed 6 November 2023].

Hourdequin M. 2016. Justice, recognition and climate change. In Climate justice and geoengineering: ethics and policy in the atmospheric anthropocene. Edited by C.J. Preston. London: Rowman & Littlefield International, Ltd. pp. 33–48.

Hügel S., Davies A.R. 2020. Public participation, engagement, and climate change adaptation: a review of the research literature. WIREs Climate Change, 11(4).

Illalba Morales M.L., Ruiz Castañeda W., Robledo Velásquez J. 2023. Configuration of inclusive innovation systems: function, agents and capabilities. Research Policy, 52(7).

IPCC. 2022a. Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. In Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Edited by H.O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, et al. et al. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 3056p.

IPCC. 2022b. Annex II: glossary [Möller, V., R. van Diemen, J.B.R. Matthews, C. Méndez, S. Semenov, J.S. Fuglestvedt, A. Reisinger (eds.)]. In Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Edited by H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, et al. et al. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. pp. 2897–2930.

Jafry T., Mikulewicz M., Helwig K. (Editors). 2018. Routledge handbook of climate justice. Routledge, London.

Jahanger A. 2023. Structural transformation and political economy: a new approach to inclusive growth. PLoS One, 18(8).

Jasanoff S. 1998. The fifth branch: science advisers as policymakers. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Jaworska A., Tannenbaum J. 2021. The grounds of moral status [Online]. Available from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/grounds-moral-status/#toc [accessed 6 November 2023].

Korn Ferry. 2021. Diversity, equity, and inclusion diagnostic: getting it right [Online]. Available from https://www.kornferry.com/content/dam/kornferry-v2/pdf/KornFerry_DEI_Maturity_Model_Factsheet.pdf [accessed 6 November 2023].

Light A., Rolston H. III. (Editors). 2003. Environmental ethics: an anthology. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

London A.J. 2021. For the common good: philosophical foundations of research ethics. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Lund B. 2019. Barriers to ideal transfer of climate change information in developing nations. IFLA Journal, 45(4): 334–343.

Madhesh A. 2023. The concept of inclusive education from the point of view of academics specialising in special education at Saudi universities. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1).

Maldonado J., Wang I., Eningowuk F., Iaukea L., Lascurain A., Lazrus H., et al. 2021. Addressing the challenges of climate-driven community-led resettlement and site expansion: knowledge sharing, storytelling, healing, and collaborative coalition building. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 1–11.

Malloy J.T., Ashcraft C.M. 2020. A framework for implementing socially just climate adaptation. Climatic Change, 160(1): 1–14.

Martin M.A., Boakye E.A., Boyd E., Broadgate W., Bustamante M., Canadell J.G., et al. 2022. Ten new insights in climate science 2022. Global Sustainability, 5.

McKinley T. 2010. Inclusive growth criteria and indicators: an inclusive growth index for diagnosis of country progress. Asian Development Bank Sustainable Development Working Paper Series 14. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28493/adb-wp14-inclusive-growth-criteria.pdf [accessed 6 November 2023].

Merino-Saum A. 2020. Choosing appropriate frameworks for green economy indicators. In Indicators for an inclusive green economy—manual for introductory training. Partnership for Action on Green Economy (PAGE), Geneva. pp. 17–35.

Mistry J., Bilbao B.A., Berardi A. 2016. Community owned solutions for fire management in tropical ecosystems: case studies from Indigenous communities of South. Philosophical Transactions, 371: 1–10.

Moore G.E. 1903. Principia ethica. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Mozumder N.A. 2022. Can ethical political leadership restore public trust in political leaders? Public Organization Review, 22, 821–835.

Mustaniemi-Laakso M., Katsui H., Heikkilä M. 2023. Vulnerability, disability, and agency: exploring structures for inclusive decision-making and participation in a responsive state. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law, 36(4): 1581–1609.

Norton A. 2019. Climate justice and the IPCC special report on land. International Institute of Environment and Development (IIED). Available from https://www.iied.org/climate-justice-ipcc-special-report-land [accessed 15 October 2022].

OECD. 2015. Innovation policies for inclusive growth. OECD, Paris [accessed 6 November 2023].

OECD. 2020. What does “Inclusive governance” mean? Clarifying theory and practice [Online]. Available from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/what-does-inclusive-governance-mean_960f5a97-en.

Osborne S.(Editor). 2010. The neew public governance? Emerging perspectives on the theory and practice of public governance. Routledge, London.

Oswick C., Noon M. 2014. Discourses of diversity, equality and inclusion: trenchant formulations or transient fashions? British Journal of Management, 25(1): 23–39.

Özbilgin M., Chanlat J.F. (Editors). 2017. Management and diversity: perspectives from different national contexts. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley.

Parraguez-Vergara E., Contreras B., Clavijo N., Villegas V., Paucar N., Ther F., 2018. Does indigenous and campesino traditional agriculture have anything to contribute to food sovereignty in Latin America? Evidence from Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Guatemala and Mexico. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 326–341.

Pham H., Saner M. 2021. A systematic literature review of inclusive climate change adaption. Sustainability.

Pringle P. 2011. AdaptME toolkit for monitoring and evaluation of adaptation activities, manual. United Kingdom Climate Impacts Programme (UKCIP). Available from www.seachangecop.org/node/116 [accessed 6 November 2023].

Ramachandran N., Di Matteo C. 2023. Exploring inclusive cities for migrants in the UK and Sweden: a scoping review. Social Inclusion, 11(3): 162–174.

Robinson M. 2018. Climate justice: hope, resilience, and the fight for a sustainable future. Bloomsbury Publishing, New York.

Roche D.G., Granados M., Austin C.C., Wilson S., Mitchell G.M., Smith P.A., et al. 2020. Open government data and environmental science: a federal Canadian perspective. Facets (Ottawa), 5(1): 942–962.

Saner M. 2006. Citizenship engagement, biotechnology and ICTs: are there any inherent problems? Techné: Research in Philosophy and Technology, 9(3): 14–22.

Schipper E.L.F., Revi A., Preston B.L., Carr E.R., Eriksen S.H., Fernandez-Carril L.R., et al. 2022. Climate resilient development pathways. In Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Edited by H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, et al. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. pp. 2655–2807.

Schirch L. (Editor). 2021. Social media impacts on conflict and democracy: the techtonic shift. Routledge, London.

Schlosberg D. 2012. Climate justice and capabilities: a framework for adaptation oolicy. Ethics & International Affairs, 26(4): 445–461.

Schönfeld M. 1992. Who or what has moral standing? American Philosophical Quarterly, 29(4): 353–362. Available from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20014430 [accessed 6 November 2023].

Singer P. 1974. All Animals are Equal. Phylosophic Exchange 1 (5): 103–116. https://iseethics.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/singer-peter-all-animals-are-equal-original.pdf [accessed 6 November 2023].

Singer P. 1981. The expanding circle: ethics and sociobiology. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Singh C., Iyer S., New M.G., Few R., Kuchimanchi B., Segnon A.C., Morchain D. 2022. Interrogating “effectiveness” in climate change adaptation: 11 guiding principles for adaptation research and practice. Climate and Development, 14(7): 650–664.

Smit B., Pilifosova O. 2001. Adaptation to climate change in the context of sustainable development and equity. In Climate change 2001: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability—Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Smit B., Wandel J. 2006. Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Global Environmental Change, 16(3): 282–292.

Smith J.L. 2017. I, River? New materialism, riparian non-human agency and the scale of democratic reform. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 58(1): 99–111.

Smucker T.A., Oulu M., Nijbroek R., 2020. Foundations for convergence: sub-national collaboration at the nexus of climate change adaptation, disaster risk reduction, and land restoration under multi-level governance in Kenya. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51: 101834.

Swan A. 2012. Policy guidelines for the development and promotion of open access [Online]. Available from https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc141806/m2/1/high_res_d/215863e.pdf [accessed 6 November 2023].

Tagliari M.M., Levis C., Flores B., Dias Blanco G., Freitas C., Bogoni J., et al., 2021. Collaborative management as a way to enhance Araucaria Forest resilience. Associacao Brasileira de Ciencia Ecologica e Conservacao, 131–142.

Tahiru A., Sackey B., Owusu G., Bawakyillenuo S. 2019. Building the adaptive capacity for livelihood improvements of Sahel Savannah farmers through NGO-led adaptation interventions.Climate Risk Management, 26: 100197.

Tangirala N. 2022. Integrating equity, diversity, and Inclusion into municipal climate action. The Partners for Climate Protection Program. Available from https://assets-global.website-files.com/6022ab403a6b2126c03ebf95/62e3058d83c7af7982e75f23_pcp-integrating-equity-diversity-and-inclusion-into-municipal-climate-action.pdf [accessed 6 November 2023].

Taylor P.W. 1986. Respect for nature: a theory of environmental ethics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Thompson D.F. 2019. Political ethics, international encyclopedia of ethics. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, UK.

Tschakert P., Machado M. 2012. Gender justice and rights in climate change adaptation: opportunities and pitfalls. Ethics and Social Welfare, 6(3): 275–289.

Tschakert P., Schlosberg D., Celermajer D., Rickards L., Winter C., Thaler M., et al. 2021. Multispecies justice: climate-just futures with, for and beyond humans. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Climate Change, 12(2): e699–en/a.

UN WomenWatch. 2009. Women, gender equality and climate change [Online]. Available from https://www.un.org/womenwatch/feature/climate_change/downloads/Women_and_Climate_Change_Factsheet.pdf [accessed 6 November 2023].

United Nations (UN). 2019. Climate justice. [Online]. Available from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/05/climate-justice/. [accessed 6 November 2023].

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). 2007. Towards Inclusive Governance: Promoting the Participation of Disadvantaged groups in Asia-Pacific. https://www.asia-pacific.undp.org/content/rbap/en/home/library/democratic_governance/towards-inclusive-governance.html [accessed 6 November 2023].

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). 2020. Strategies for supporting inclusive innovation: insights from South-East Asia. https://www.undp.org/publications/strategies-supporting-inclusive-innovation [accessed 6 November 2023].

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2017. A guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000248254 [accessed 6 November 2023].

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). 2015. Habitat-III-Issue-Paper-1_Inclusive-Cities. [Online]. Available from https://www.alnap.org/help-library/habitat-iii-issue-papers-1-inclusive-cities [accessed 6 November 2023].

Vian T. 2020. Anti-corruption, transparency and accountability in health: concepts, frameworks, and approaches. Global Health Action, 13(Suppl. 1): 1694744.

W. K. Kellogg Foundation. 2004. Logic model development guide [Online]. Available from https://wkkf.issuelab.org/resource/logic-model-development-guide.html [accessed 6 November 2023].

Walsh C. 2019. Integration of expertise or collaborative practice? Coastal management and climate adaptation at the Wadden Sea. Ocean and Coastal Management, 167: 78–86.

Waluchow W.J. 2003. The dimensions of ethics: an introduction to ethical theory. Broadview Press, Peterborough.

Whyte K. 2020. Too late for indigenous climate justice: ecological and relational tipping points. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 11(1): e603.

Wing O.E.J., Lehman W., Bates P.D., Sampson C.C., Quinn N., Smith A.M., et al. 2022. Inequitable patterns of US flood risk in the Anthropocene. Nature Climate Change, 12(2): 156–162.

Wolbring G., Lillywhite A. 2021. The case of disabled people. Societies, 11(2): 1–34.