Introduction

Aquatic invasive plants are a major threat to freshwater ecosystems, where they negatively affect native aquatic plant and fish communities, disrupt food webs, interfere with recreation, and decrease property values (

Zhang and Boyle 2010;

Schultz and Dibble 2012;

Olden and Tamayo 2014;

Tasker et al. 2022;

Carey et al. 2023). While preventing spread to new waterbodies is the best option for limiting negative impacts, controlling within-lake spread and abundance becomes the primary means of mitigating impacts once they have established within a waterbody (

Simberloff et al. 2013). Thus, evaluating and improving control effectiveness is crucial for soundly investing limited resources for management.

The invasive macroalga, starry stonewort (

Nitellopsis obtusa Desv. (J. Groves)), has been a challenge for lake managers for decades in the Midwestern United States (

Pullman and Crawford 2010;

Larkin et al. 2018). First discovered in the 1970s in Quebec, it has spread to the Laurentian Great Lakes and inland lakes in the U.S. and Canada (

Geis et al. 1981;

Karol and Sleith 2017). Its dense growth is associated with declines in native macrophytes (

Brainard and Schulz 2017;

Ginn et al. 2021), facilitation of invasive zebra mussels and cyanobacteria blooms (

Harrow-Lyle and Kirkwood 2020), and alteration of benthic water chemistry (

Harrow-Lyle and Kirkwood 2021). Dense

N. obtusa growth can impair dock access, boating, fishing, and swimming. While control efforts have been ongoing in some areas for ca. 20 years, there were no published laboratory or mesocosm studies on the efficacy of commonly used algaecides for

N. obtusa until recently (

Pokrzywinski et al. 2021;

Wersal 2022;

Glisson et al. 2022a). Evaluation of effectiveness of in-situ treatments is similarly lacking, with published field studies limited to a single lake in Minnesota (

Glisson et al. 2018;

Carver et al. 2022). To advance

N. obtusa management, there is a critical need to understand the effectiveness of ongoing management across a broader range of lakes.

Copper-based algaecides have been the primary means of attempting to control

N. obtusa in the Midwestern U.S. (

Pullman and Crawford 2010;

Glisson et al. 2018;

Larkin et al. 2018). Aquatic pesticide regulations are stricter in Canada (

Anderson et al. 2021), where algaecides have not been used on

N. obtusa to our knowledge. Copper has been used for nuisance algae control for decades (

Lembi 2014) and can be effective for macroalgae control in small waterbodies (e.g., ponds, rice paddies,

McIntosh 1974;

Guha 1991). However, effectiveness against macroalgae in lakes has been less thoroughly studied. Evidence from laboratory and mesocosm trials shows modest control of

N. obtusa at concentrations at or near maximum product-labeled rates of 1 mg Cu L

−1 (

Pokrzywinski et al. 2021;

Wersal 2022;

Glisson et al. 2022a). However, these concentrations are difficult to achieve and maintain under operational field settings. In addition, because copper algaecides are non-systemic (i.e., not translocated through plant tissues), repeat treatments are often needed throughout the growing season to keep up with substantial seasonal growth (

Glisson et al. 2018;

Glisson et al. 2022b). This has raised concerns about copper algaecide use for

N. obtusa given copper's toxicity to aquatic organisms (e.g.,

Mastin and Rodgers 2000;

Christenson et al. 2014;

Closson and Paul 2014;

Kang et al. 2022) and its persistence and accumulation in sediments (

Han et al. 2001). Given known and potential impacts of copper to freshwater systems, the effectiveness of continued use of copper-based algaecides for

N. obtusa should be evaluated. Ideally, this could support achievement of control objectives balanced with minimizing copper inputs into the natural environment.

As an alternative to, and sometimes in combination with copper algaecides, physical removal methods have been implemented for

N. obtusa control. For example, mechanical harvesting has been used to manage

N. obtusa in some lakes (

Glisson et al. 2018). Other methods, such as hand-pulling, diver-assisted suction harvesting (DASH), and drawdowns have also been implemented. The outcomes of these treatment efforts are often not recorded, analyzed, or reported due to time constraints and other challenges. When reported, they have largely been confined to grey literature or presentations, and, importantly, not synthesized with other treatment attempts. To enable sound recommendations regarding non-chemical and combination management strategies, comprehensive assessment is needed.

State agencies, lake groups, and contractors in the Midwest U.S. routinely conduct systematic surveys of

N. obtusa lakes concurrent with management. Leveraging these data would allow for large-scale analysis of treatment effectiveness. Such approaches have advanced science-based management for other invasive aquatic plants (e.g.,

Kujawa et al. 2017;

Nault et al. 2018;

Mikulyuk et al. 2020;

Verhoeven et al. 2020) and are urgently needed for

N. obtusa.

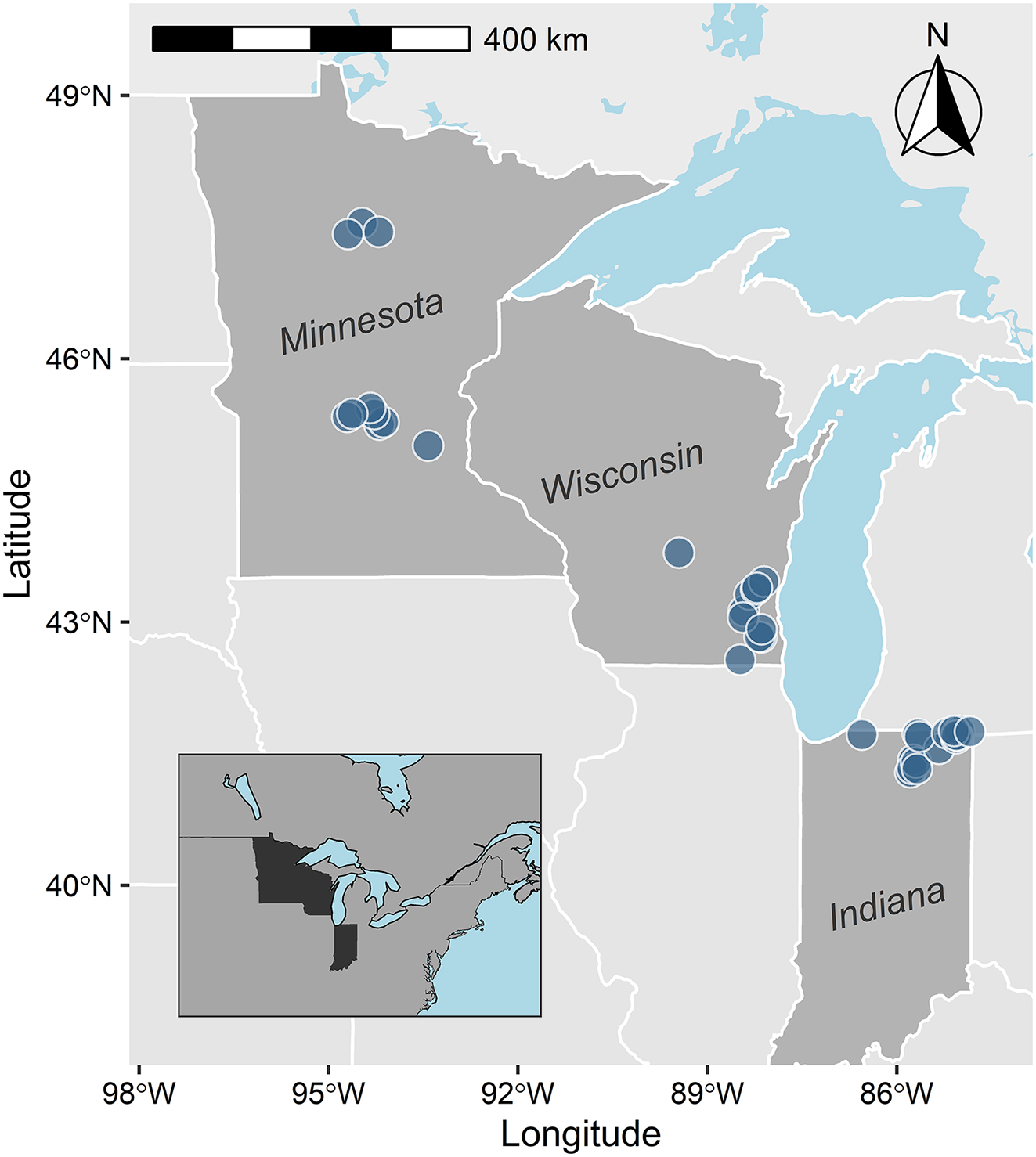

We used data from the first 5–10 years of N. obtusa management in three Midwestern states to evaluate the effectiveness of current management approaches. Specifically, our objectives were to: (1) document the state of N. obtusa management in the Midwestern U.S.; (2) assess whether common management approaches are reducing the extent and abundance of N. obtusa; (3) identify the most promising approaches for control; and (4) develop recommendations for improved monitoring of management effectiveness.

Discussion

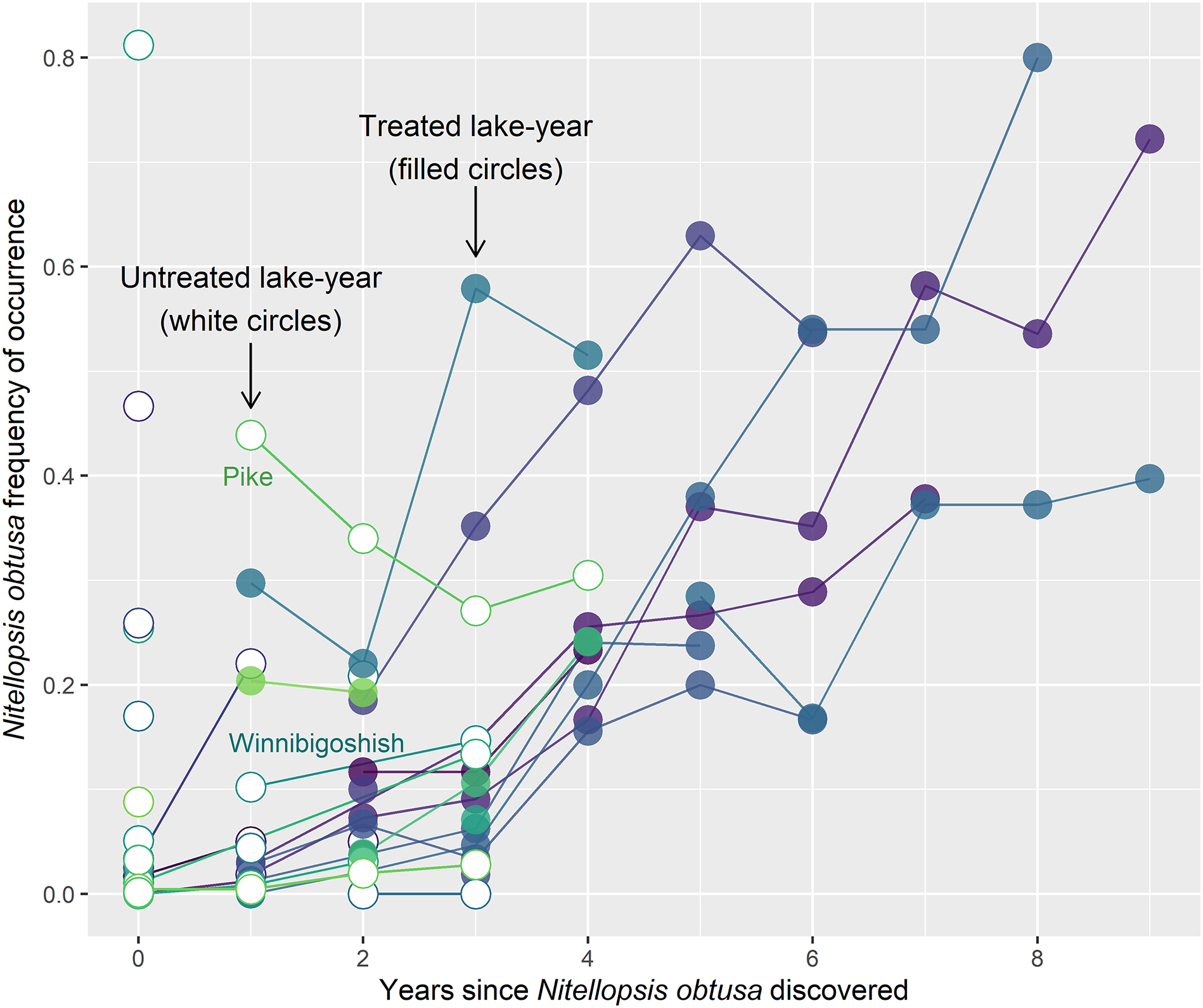

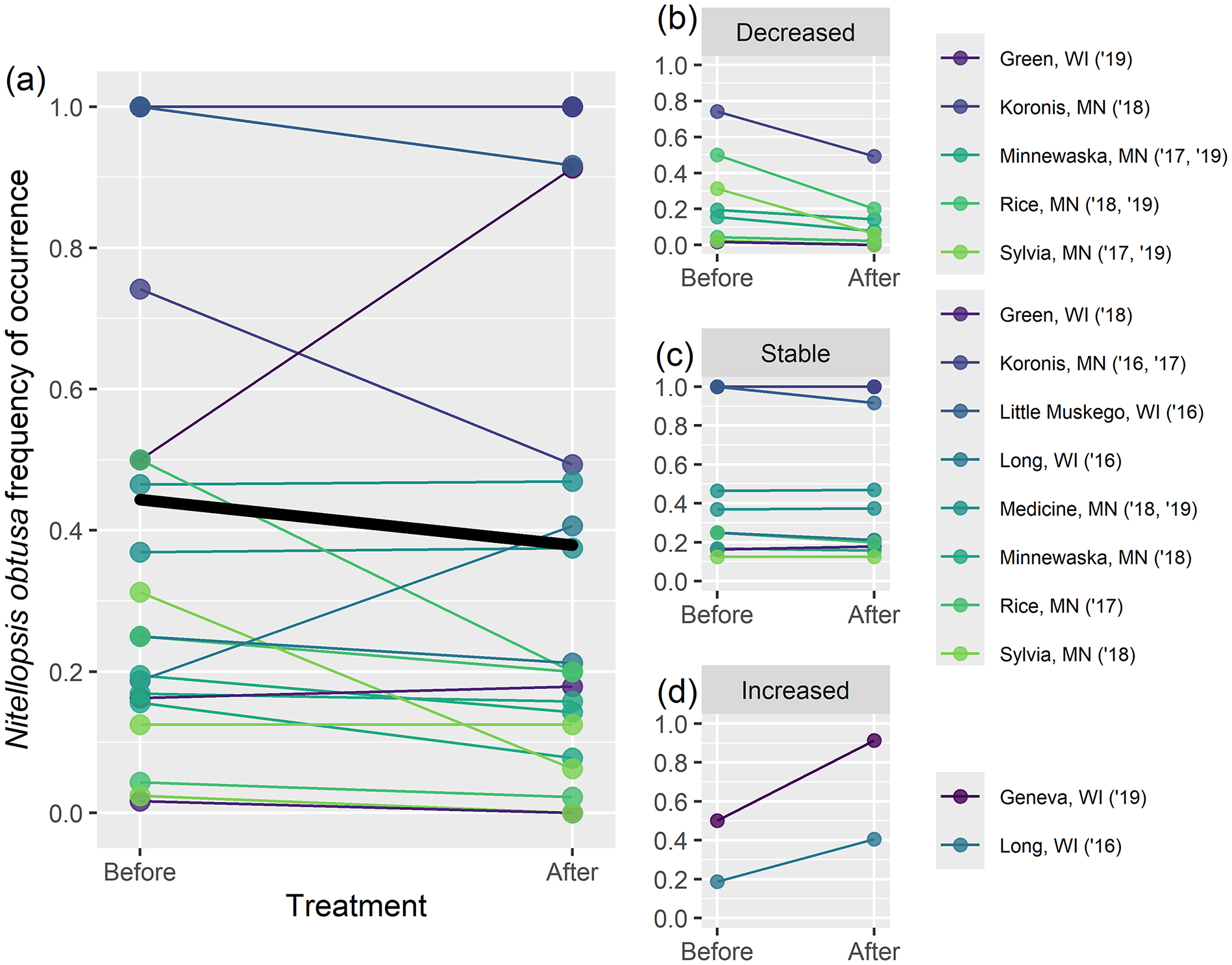

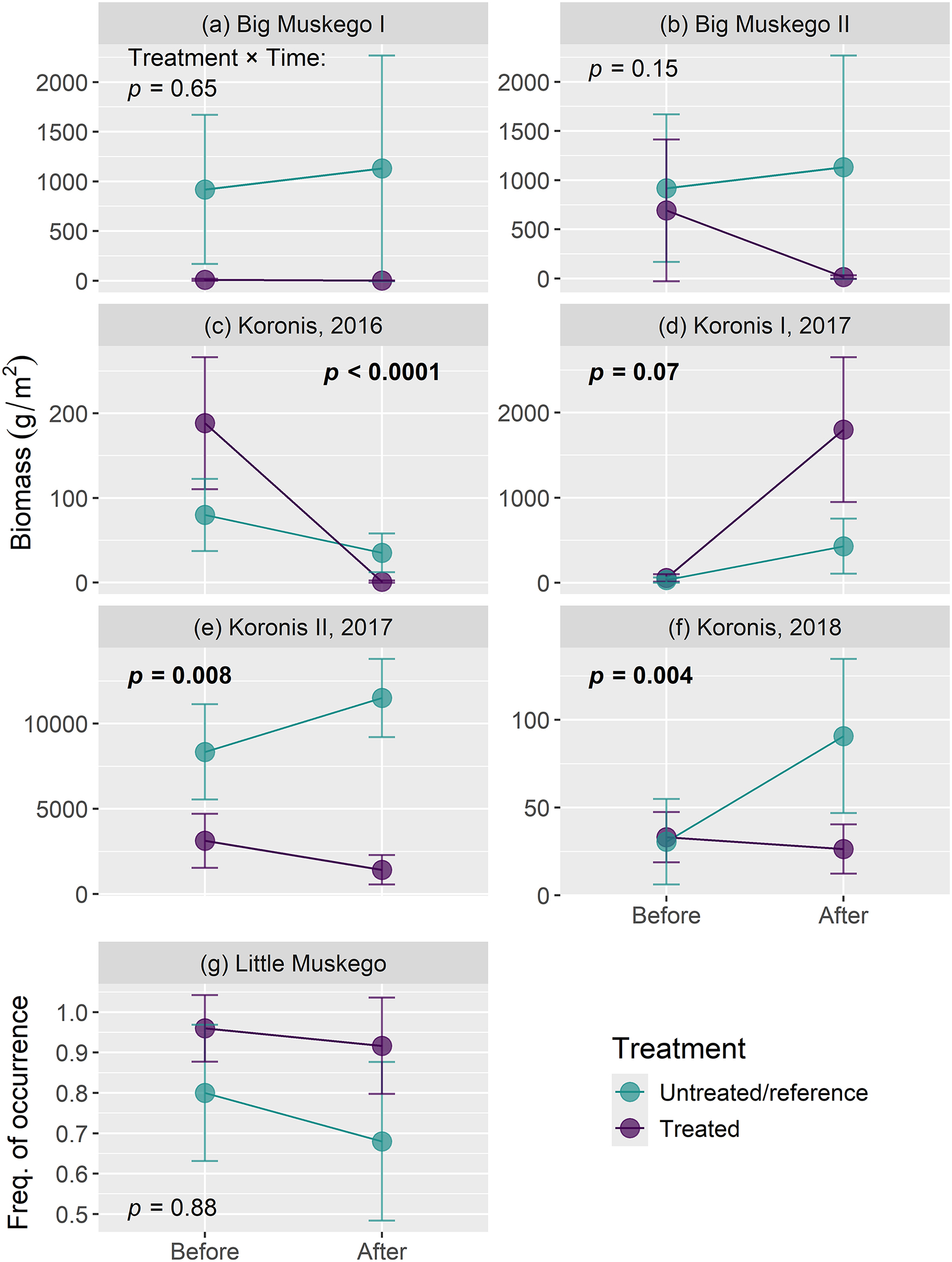

This study provides the first quantitative synthesis of

N. obtusa management outcomes. At the largest spatial scale evaluated, current algaecide treatments were not effective for reducing the extent of

N. obtusa within infested lakes (

Table 2,

Fig. 2), and there was evidence of increased abundance following such treatments (

Table 2). At a finer scale, within individual treatment areas, there was significant reduction in

N. obtusa frequency of occurrence following algaecide treatments overall (

Fig. 3a), but outcomes were highly variable (

Fig. 3b–

3d) and there was not concomitant reduction in

N. obtusa abundance. The most robust survey data available, from BACI sampling, showed that local

N. obtusa biomass was consistently reduced with algaecide treatment in one lake, but biomass and frequency of occurrence were not reduced in two others (

Fig. 5). The paucity of such robust data are a critical gap in monitoring that impedes assessment of management effectiveness. Similarly, it appears likely that

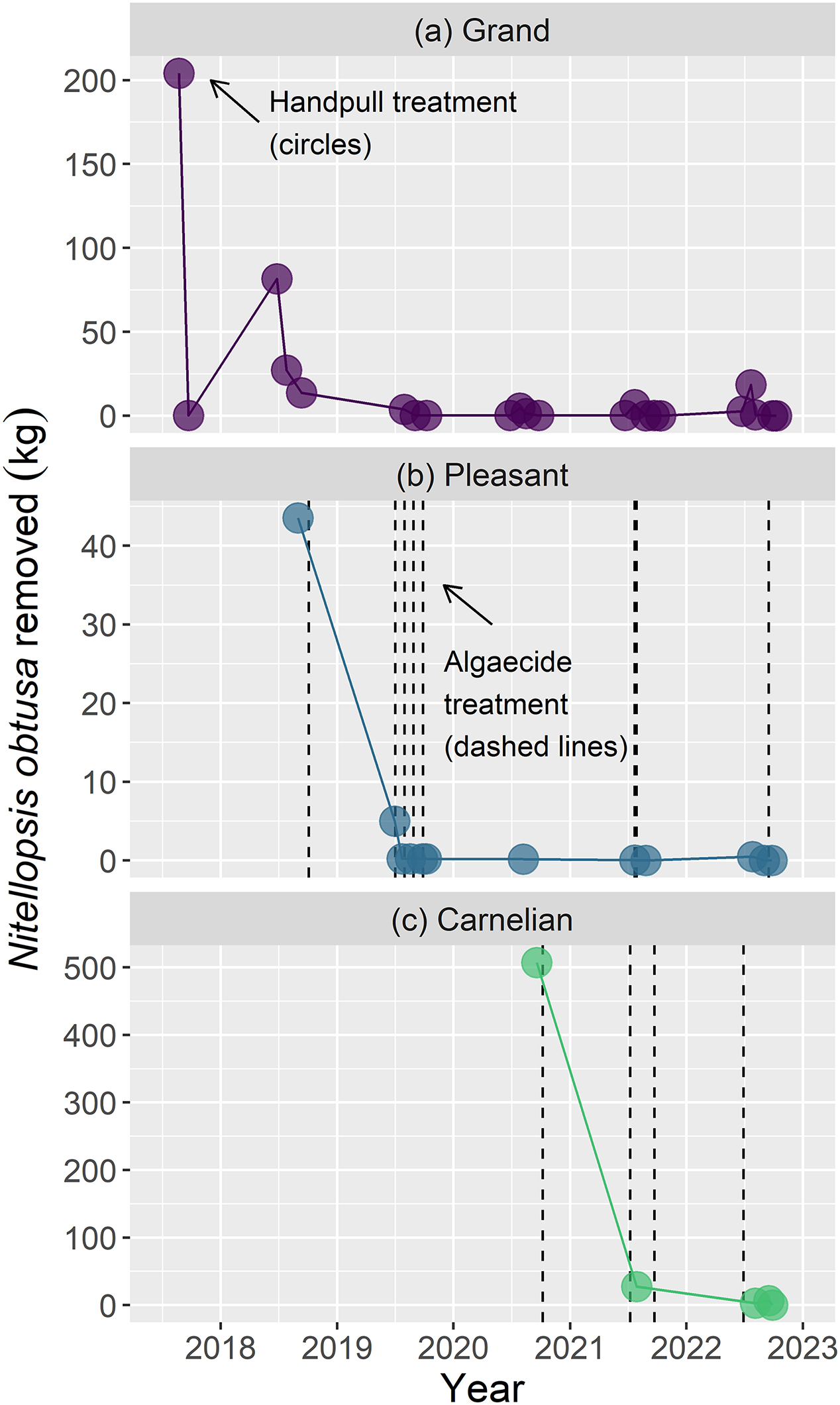

N. obtusa will continue to spread within treated lakes, but whether such expansion would markedly differ in the absence of treatment is difficult to assess given a lack of monitoring of untreated reference lakes. Encouragingly, hand pulling of small infestations, alone or in combination with algaecide treatments, depleted

N. obtusa to nearly undetectable levels (

Fig. 4)

On a whole-lake scale, we expected to see declines in

N. obtusa frequency and abundance with algaecide treatments, especially over time, given patterns observed for other invasive macrophytes. For example, Eurasian watermilfoil (

Myriophyllum spicatum) significantly decreased in lakes over time with continued treatment (

Kujawa et al. 2017), as did curly-leaf pondweed (

Potamogeton crispus) (

Verhoeven et al. 2020). The lack of lake-wide

N. obtusa control with algaecides could be interpreted in several ways. One possible explanation is that these algaecide treatments may simply not slow the spread and reduce the abundance of

N. obtusa within a lake; if so, then alternative approaches need to be developed, and continued treatments should be evaluated in light of limited resources for lake management and potential non-target impacts of algaecides (e.g.,

Mikulyuk et al. 2020).

Native Characean macroalgae such as

Chara spp., which often co-occur with

N. obtusa (

Ginn et al. 2021;

Harrow-Lyle and Kirkwood 2022), are sensitive to copper algaecides (

McIntosh 1974;

Guha 1991). Reduction of native Characeae following

N. obtusa algaecide treatment has not been evaluated in the scientific literature to our knowledge, but if substantial, could consequently reduce competition for

N. obtusa and thereby exacerbate its expansion. Native Characeae occupy a distinct niche in the macrophyte community, fostering fish and invertebrate communities that differ from those associated with vascular macrophytes (

Blindow et al. 2014;

Schneider et al. 2015). The extent to which

N. obtusa may perform a similar role as native Characeae in North America is unclear. Thus, potential harm to native Characean macroalgae should be considered when deciding whether to treat

N. obtusa. Complicating matters, however, is evidence that native Characeae may be particularly susceptible to displacement by

N. obtusa (

Wagner 2021), so there is also potential risk to native Characeae from unabated

N. obtusa spread. Additionally, field and lab studies suggest that copper-based algaecide treatment could foster asexual reproduction of

N. obtusa via increased bulbil production and/or sprouting (

Glisson et al. 2018;

Glisson et al. 2022a). In sum, sustained application of copper algaecides may negatively impact native Characeae while not effectively controlling

N. obtusa spread; but native Characeae could also be negatively impacted by

N. obtusa dominance. These complexities require careful consideration given the amount of copper being added to lakes for

N. obtusa control (ca. 20 tons for study lakes during this monitoring period), paired with uncertainty about the long-term ecological impacts of

N. obtusa invasion.

Interestingly, the only two lakes where

N. obtusa was not managed, and surveys spanned ≥2 year(s) (Pike Lake, Wisconsin; Like Winnibigoshish, Minnesota), exhibited decreasing and minimally increasing

N. obtusa frequency, respectively, contrasting with other lakes in the region that were regularly managed and showed consistent

N. obtusa expansion (

Fig. 2). These patterns may be due to sub-optimal conditions for

N. obtusa growth in these lakes compared to others; nonetheless, these patterns, combined with disappointing control outcomes and concerns about toxicity risks with repeated copper use, have led the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources to substantially limit permits for chemical control of

N. obtusa. The generally decreasing

N. obtusa frequency of occurrence over time in Pike Lake is particularly compelling. This pattern demonstrates the value of monitoring some infested lakes while refraining from management, and further suggests the possibility of this approach being as or more beneficial than algaecide treatment—at least at a whole-lake scale. Along with management status, other factors in a waterbody, such as water clarity, water chemistry, and sediment composition, should also be monitored in infested lakes to determine how they may impact

N. obtusa abundance and management effectiveness. Similar to the case of Eurasian watermilfoil, a lack of

N. obtusa management does not seem to condemn a lake to be fully overtaken (

Kujawa et al. 2017).

A second potential explanation of the lack of whole-lake response of

N. obtusa to algaecide treatment could be that there has been insufficient treatment effort in terms of extent or concentrations, or use of poor-performing products and product combinations. In terms of extent, we did not have complete information on the area of each

N. obtusa infestation, but entire populations were not always targeted for treatment, especially in lakes where populations covered most of the littoral zone, such as Lake Koronis (Minnesota). Treatment of greater proportions of

N. obtusa populations could lead to greater lake-wide reductions. However, most states have regulations that restrict how much of the littoral zone can be treated, so this is not always possible. Regarding the most effective products and concentrations for

N. obtusa control, only a handful of comparative studies have been performed (

Pokrzywinski et al. 2021;

Carver et al. 2022;

Wersal 2022;

Glisson et al. 2022a). While some products appear slightly more effective than others, to date there is little evidence of a specific product or combination (Table S3) substantially outperforming others. For copper algaecides, higher copper concentrations, up to the U.S. limit of 1 mg Cu L

−1, generally perform better for

N. obtusa control (

Glisson et al. 2022a). Difficulty maintaining these concentrations for sufficient durations in the field (i.e., achieving adequate concentration-exposure time, or CET) and delivering algaecides to

N. obtusa beds, however, may have led to poor treatment outcomes. Hence, strategies such as in-water barriers, cooled-water algaecide mixtures, and drop-hose applications could result in greater treatment effectiveness with currently used products. We cannot rule out that larger-scale treatments, new chemicals/combinations, novel application methods, and greater CETs would increase effectiveness; however, our analysis demonstrates that current algaecide approaches are not reducing

N. obtusa on a whole-lake scale.

In contrast, at the scale of individual treatment areas, copper algaecide treatments were generally effective at reducing

N. obtusa frequency of occurrence (before-after analysis) and showed mixed results based on biomass (BACI analysis). Most notable were the substantial biomass reductions within most treated areas on Lake Koronis relative to untreated control areas (

Figs. 5c,

5e,

5f). The areas targeted for control on Lake Koronis were generally those with the greatest

N. obtusa biomass, and biomass reductions were consistently achieved in these areas on a yearly basis. Thus, at a smaller scale, control of

N. obtusa can be achieved with currently available algaecides, as has been observed in other recent field studies (also from Lake Koronis:

Glisson et al. 2018;

Carver et al. 2022). Reductions in

N. obtusa frequency of occurrence and biomass, however, were not observed across all lakes and treatments. For frequency of occurrence,

N. obtusa stayed stable or increased (

Figs. 3c,

3d;

Fig. 5g) in nearly as many cases as it decreased (

Fig. 3b), and we did not observe reduced

N. obtusa abundance based on before-after analysis of rake density. Even on Lake Koronis,

N. obtusa biomass significantly increased following an early-summer treatment in 2017 (

Fig. 4d, Supplementary Materials Table S2). In general, the BACI results suggest that later-season treatments and higher copper concentrations might be more effective. Nonetheless, without being able to account for other potentially influential factors (e.g., product applied, water depth, time of year), or the luxury of larger data sets encompassing many treatments varying across these factors, we cannot determine

why some treatments were more successful than others. Future BACI studies could also examine effectiveness across multiple treatments within a year (e.g.,

Glisson et al. 2018), and across years.

Contrasting results of algaecide treatment outcomes at whole-lake versus finer scales highlight different scenarios for management of N. obtusa moving forward. For populations that are already widespread and established, large reductions in extent are unlikely using current management options, and control should be focused on high-priority areas, be those areas of greatest impacts to recreation (e.g., docks and accesses) or the environment (e.g., ecologically sensitive areas, those with rare native species). Within these smaller areas, reductions in N. obtusa frequency and biomass may be achievable. For small, localized populations, containing N. obtusa and deterring within-lake spread is feasible using algaecides and some of the case-study approaches described below. The success of these containment efforts is evidenced by the lack of spread in lakes where populations were quite small, and presumably detected early (e.g., Grand, Pleasant, Carnelian, and Sylvia Lakes in Minnesota).

Before-after-control-impact studies allow rigorous inference of treatment effectiveness (

Christie et al. 2019). But a challenge for lake managers and decision makers is choosing to leave infested areas within lakes—or at a larger spatial scale, entire lakes—untreated. This is particularly difficult to do with high-concern emerging invaders like

N. obtusa, where there is strong, justified motivation to intervene. Nonetheless, monitoring untreated areas/lakes is essential for evaluating treatment effectiveness, and thereby guiding and improving future management. Where populations are small and eradication is the goal, leaving an area untreated is not realistic. However, it is fairly common that

N. obtusa is already extensive when discovered in a waterbody (see

Fig. 2), and treatment of the entire population is not feasible (e.g., due to insufficient funds, regulations, or presence of sensitive species). In these situations, areas of similar environmental conditions and

N. obtusa establishment could be paired as treatment and untreated reference site(s)—ideally with random assignment of management status. Because PI surveys are routinely conducted on numerous infested lakes, points could also be assigned as control areas without any additional work, i.e., points can simply be categorized as reference locations for subsequent analyses. With sufficient infestation extent, multiple treatment and reference sites could be monitored to increase the power of BACI analysis to detect treatment impacts (

Underwood 1991). This framework could further be scaled up to examine entire lakes as treated and untreated. Lakes such as Pike Lake (Wisconsin), where eradication is unlikely and a robust native plant community is still intact, are particularly good candidates to remain untreated for BACI analysis. In addition to elucidating treatment effectiveness, untreated reference lakes are also vital for investigations of

N. obtusa ecology and impacts, e.g., potential competition with native macrophytes (e.g.,

Glisson et al. 2022b).

Case studies, which included physical removal methods, suggested that some approaches are poor candidates for

N. obtusa management (

Table 3). Namely, a whole-lake winter drawdown on Little Muskego Lake (Wisconsin) resulted in a significant increase in

N. obtusa frequency, with the proportion of occupied points doubling the year following the drawdown (2017: 12%, 2018: 26%). Desired sediment freeze and compaction were not achieved during this treatment, which likely limited its effectiveness. Such issues are common among drawdown treatments for macrophyte control (e.g.,

Dugdale et al. 2012). Bottom dredging was also ineffective for

N. obtusa control: in Silver Lake (Wisconsin), frequency of

N. obtusa significantly increased within the managed area. Both dredging and drawdown are major disturbances of the lake bottom. In its native range,

N. obtusa was shown to be susceptible to disturbance caused by lakebed drying (

Boissezon et al. 2018). However, in its invaded range in the Midwestern U.S., we have frequently observed

N. obtusa in disturbed environments (e.g., near boat launches subject to prop wash) and consider it to at least tolerate if not outright benefit from disturbance. The drawdown and dredging in Little Muskego and Silver Lakes did lead to declines in co-dominant macrophytes, including

Myriophyllum spicatum (WDNR, unpublished data). Thus, these treatments appear to have opened up habitat that

N. obtusa was then able to colonize. These poor results, paired with the substantial cost and time commitment of whole-lake drawdown and dredging, caution against these approaches for

N. obtusa management.

Two case-study approaches that were promising were hand-pulling and DASH (

Table 3,

Fig. 4). While DASH did not significantly reduce

N. obtusa frequency of occurrence in Little Muskego and Little Cedar Lakes (Wisconsin; in 2015 and 2019, respectively), these treatments may have helped contain further spread, with frequency of occurrence largely unchanged two months following treatment, during time periods when

N. obtusa biomass is expected to still be seasonally increasing (Table 3;

Glisson et al. 2022b). Frequency of

N. obtusa occurrence did increase following DASH on Lake Sylvia (Minnesota); however, this increase was not significant and was based on relatively few survey points. This approach warrants further research as an

N. obtusa control strategy, particularly in situations where algaecides are not permitted or pose unacceptable risk to native macrophytes.

Hand pulling, alone or in combination with algaecide, did not result in statistically significant reductions of

N. obtusa frequency of occurrence in our case study analysis (however, combination treatments did reduce

N. obtusa frequency to zero occurrences in Pleasant Lake, Minnesota;

Table 3). Presence-absence measures from PI sampling grids likely underestimate the effectiveness of hand pulling given the clumped, patchy distribution of nascent

N. obtusa infestations—the context in which hand-pulling has been used. In contrast, measures of biomass removal illustrate the consistent effectiveness across lakes and over time of repeated, sustained hand pulling (

Fig. 4). Sustained hand pulling resulted in similar reductions of Eurasian watermilfoil over a comparable time period (

Gagné and Lavoie 2023). Along with DASH, hand pulling is a targeted method for directly removing

N. obtusa while minimizing damage to native macrophytes. However, due to the time and effort needed to conduct hand pulls, this strategy is most feasible for small infestations in shallow areas with low turbidity.